Perospirone

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Lullan |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 92%[1] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic[1] |

| Elimination half-life | 1.9–2.5 hours[1][2] |

| Excretion | Renal (0.4% as unchanged drug)[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

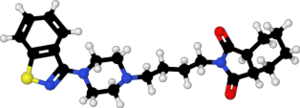

| Formula | C23H30N4O2S |

| Molar mass | 426.58 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Perospirone (Lullan) is an atypical antipsychotic of the azapirone family.[1] It was introduced in Japan by Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma in 2001 for the treatment of schizophrenia and acute cases of bipolar mania.[3][4]

Medical uses

[edit]Its primary uses are in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar mania.[3][4]

Schizophrenia

[edit]In a clinical trial that compared it to haloperidol in the treatment of schizophrenia it was found to produce significantly superior overall symptom control.[5] In another clinical trial perospirone was compared with mosapramine and produced a similar reduction in total PANSS score, except with respect to the blunted affect part of the PANSS negative score, in which perospirone produced a significantly greater improvement.[6] In an open-label clinical trial comparing aripiprazole with perospirone there was no significant difference between the two treatments discovered in terms of both efficacy and tolerability.[7] In 2009 a clinical trial found that perospirone produced a similar reduction of PANSS score than risperidone and the extrapyramidal side effects was similar in both frequency and severity between groups.[8]

A meta-analysis published in 2013 found that it is statistically significantly less efficacious than other second-generation antipsychotics.[9]

Adverse effects

[edit]Has a higher incidence of extrapyramidal side effects than the other atypical antipsychotics, but still less than that seen with typical antipsychotics.[1][10] A trend was observed in a clinical trial comparing mosapramine with perospirone that favoured perospirone for producing less prominent extrapyramidal side effects than mosapramine although statistical significant was not reached.[6] It may produce less QT interval prolongation than zotepine, as in one patient who had previously been on zotepine switching to perospirone corrected their prolonged QT interval.[11] It also tended to produce less severe extrapyramidal side effects than haloperidol in a clinical trial comparing the two (although statistical significance was not reached).[5]

Discontinuation

[edit]The British National Formulary recommends a gradual withdrawal when discontinuing antipsychotics to avoid acute withdrawal syndrome or rapid relapse.[12] Symptoms of withdrawal commonly include nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite.[13] Other symptoms may include restlessness, increased sweating, and trouble sleeping.[13] Less commonly there may be a felling of the world spinning, numbness, or muscle pains.[13] Symptoms generally resolve after a short period of time.[13]

There is tentative evidence that discontinuation of antipsychotics can result in psychosis.[14] It may also result in reoccurrence of the condition that is being treated.[15] Rarely tardive dyskinesia can occur when the medication is stopped.[13]

Pharmacology

[edit]Perospirone binds to the following receptors with very high affinity (as an antagonist unless otherwise specified):[9][16][17][18][19][20]

And the following receptor with high affinity:[9]

- H1 (inverse agonist)

And the following with moderate affinity:[9]

And with low affinity for the following receptor:[9]

See also

[edit]- Azapirone

- Blonanserin — another second-generation antipsychotic that's only approved for clinical use in East Asia

- Mosapramine

- Zotepine

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Onrust SV, McClellan K (2001). "Perospirone". CNS Drugs. 15 (4): 329–37, discussion 338. doi:10.2165/00023210-200115040-00006. PMID 11463136. S2CID 262520276.

- ^ Yasui-Furukori N, Furukori H, Nakagami T, Saito M, Inoue Y, Kaneko S, Tateishi T (August 2004). "Steady-state pharmacokinetics of a new antipsychotic agent perospirone and its active metabolite, and its relationship with prolactin response". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 26 (4): 361–365. doi:10.1097/00007691-200408000-00004. PMID 15257064. S2CID 43362616.

- ^ a b de Paulis T (January 2002). "Perospirone (Sumitomo Pharmaceuticals)". Current Opinion in Investigational Drugs. 3 (1): 121–129. PMID 12054062.

- ^ a b "Now on the Market : New Antipsychotic "Lullan® Tablets" - serotonin-dopamine antagonist originated in Japan". Sumitomo Pharmaceuticals 2001 | News Release | Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma. 8 February 2001. Archived from the original on 24 February 2006.

- ^ a b Murasaki M, Koyama T, Machiyama Y, et al. (1997). "Clinical evaluation of a new antipsychotic, perospirone HCl, on schizophrenia: a comparative double-blind study with haloperidol". Rinsho Hyoka. 24 (2–3): 159–205.

- ^ a b Kudo Y, Nakajima T, Saito M, et al. (1997). "Clinical evaluation of a serotonin-2 and dopamine-2 receptor antagonist (SDA), perospirone HCl on schizophrenia: a comparative double-blind study with mosapramine HCl". Rinsho Hyoka. 24 (2–3): 207–48.

- ^ Takekita Y, Kato M, Wakeno M, Sakai S, Suwa A, Nishida K, et al. (January 2013). "A 12-week randomized, open-label study of perospirone versus aripiprazole in the treatment of Japanese schizophrenia patients". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 40: 110–114. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.09.010. PMID 23022672. S2CID 10315774.

- ^ Okugawa G, Kato M, Wakeno M, Koh J, Morikawa M, Matsumoto N, et al. (June 2009). "Randomized clinical comparison of perospirone and risperidone in patients with schizophrenia: Kansai Psychiatric Multicenter Study". Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 63 (3): 322–328. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.01947.x. PMID 19566763. S2CID 23636639.

- ^ a b c d e Kishi T, Iwata N (September 2013). "Efficacy and tolerability of perospirone in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". CNS Drugs. 27 (9): 731–741. doi:10.1007/s40263-013-0085-7. PMID 23812802. S2CID 11543666.

- ^ "Perospirone Hydrochloride". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. 23 September 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ Suzuki Y, Watanabe J, Sugai T, Fukui N, Ono S, Tsuneyama N, et al. (April 2012). "Improvement in QTc prolongation induced by zotepine following a switch to perospirone". Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 66 (3): 244. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2012.02321.x. PMID 22443250. S2CID 32269750.

- ^ Joint Formulary Committee, BMJ, ed. (March 2009). "4.2.1". British National Formulary (57 ed.). United Kingdom: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-85369-845-6.

Withdrawal of antipsychotic drugs after long-term therapy should always be gradual and closely monitored to avoid the risk of acute withdrawal syndromes or rapid relapse.

- ^ a b c d e Haddad PM, Dursun S, Deakin B (2004). Adverse Syndromes and Psychiatric Drugs: A Clinical Guide. OUP Oxford. p. 207-216. ISBN 9780198527480.

- ^ Moncrieff J (July 2006). "Does antipsychotic withdrawal provoke psychosis? Review of the literature on rapid onset psychosis (supersensitivity psychosis) and withdrawal-related relapse". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 114 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00787.x. PMID 16774655. S2CID 6267180.

- ^ Sacchetti E, Vita A, Siracusano A, Fleischhacker W (2013). Adherence to Antipsychotics in Schizophrenia. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 85. ISBN 9788847026797.

- ^ Roth BL, Driscol, J (12 January 2011). "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ Hirose A, Kato T, Ohno Y, Shimizu H, Tanaka H, Nakamura M, Katsube J (July 1990). "Pharmacological actions of SM-9018, a new neuroleptic drug with both potent 5-hydroxytryptamine2 and dopamine2 antagonistic actions". Japanese Journal of Pharmacology. 53 (3): 321–329. doi:10.1254/jjp.53.321. PMID 1975278.

- ^ Kato T, Hirose A, Ohno Y, Shimizu H, Tanaka H, Nakamura M (December 1990). "Binding profile of SM-9018, a novel antipsychotic candidate". Japanese Journal of Pharmacology. 54 (4): 478–481. doi:10.1254/jjp.54.478. PMID 1982326.

- ^ Odagaki Y, Toyoshima R (2007). "5-HT1A receptor agonist properties of antipsychotics determined by [35S]GTPgammaS binding in rat hippocampal membranes". Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology & Physiology. 34 (5–6): 462–466. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04595.x. PMID 17439416. S2CID 22450517.

- ^ Seeman P, Tallerico T (March 1998). "Antipsychotic drugs which elicit little or no parkinsonism bind more loosely than dopamine to brain D2 receptors, yet occupy high levels of these receptors". Molecular Psychiatry. 3 (2): 123–134. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4000336. PMID 9577836. S2CID 16484752.