Pilaf

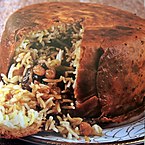

Baghali polo, an Iranian dish, made from rice and fava bean | |

| Alternative names | Polao, pulao, plao, pela, pilav, pilov, pallao, pilau, pelau, palau, polau, pulaav, palaw, palavu, plov, plovas, palov, polov, polo, polu, kurysh, fulao, fulaaw, fulav, fulab, osh, aş, paloo, piles, kürüch |

|---|---|

| Course | Main |

| Region or state | Central Asia, West Asia, South Asia, South Caucasus, East Africa, Eastern Europe |

| Serving temperature | Hot |

| Main ingredients | Rice, stock or broth, spices, meat, vegetables, dried fruits |

Pilaf (US: /ˈpiːlɑːf/), pilav or pilau (UK: /ˈpiːlaʊ, piːˈlaʊ/) is a rice dish, usually sautéed, or in some regions, a wheat dish, whose recipe usually involves cooking in stock or broth, adding spices, and other ingredients such as vegetables or meat,[1][note 1][2][note 2] and employing some technique for achieving cooked grains that do not adhere to each other.[3][note 3][4][note 4]

At the time of the Abbasid Caliphate, such methods of cooking rice at first spread through a vast territory from Iran to Greece, and eventually to a wider world. The Valencian (Spanish) paella,[5][note 5] and the Indian pilau or pulao,[6][note 6] and biryani,[7][note 7] evolved from such dishes.

Pilaf and similar dishes are common to Middle Eastern, West Asian, Balkan, Caribbean, South Caucasian, Central Asian, East African, Eastern European, Latin American, Maritime Southeast Asia, and South Asian cuisines; in these areas, they are regarded as staple dishes.[8][9][10][11][12]

Etymology

[edit]According to the Oxford English Dictionary, Third Edition (2006) the English word pilaf, which is the later and North American English form, is a borrowing from Turkish, its etymon, or linguistic ancestor, the Turkish pilav, whose etymon is the Persian pilāv; "pilaf" is found more commonly in North American dictionaries than pilau, all from the Persian pilav.[13][14] [15]

The British and Commonwealth English spelling, pilau, has etymon Persian pulaw (in form palāv, pilāv, or pulāv in the 16th century) and Urdu pulāv ("dish of rice and meat"), from Persian[16] pulāv ("Side dishes, spices, meat, vegetables, even plain rice "), the Tamil Pulukku ("Dravidian (compare Tamil puḷukku (adjective) simmered, (noun) boiled or parboiled food, puḷukkal cooked rice); in turn probably from Sanskrit pulāka ("ball of rice").[1]

History

[edit]

Although the cultivation of rice had spread much earlier from India to Central and West Asia, it was at the time of the Abbasid Caliphate that methods of cooking rice which approximate modern styles of cooking pilaf at first spread through a vast territory from Spain to Afghanistan, and eventually to a wider world. The Spanish paella,[5][note 8] and the South Asian pilau or pulao,[6][note 9] and biryani,[7][note 10] evolved from such dishes.

According to author K. T. Achaya, the Indian epic Mahabharata mentions an instance of rice and meat cooked together. Also, according to Achaya, "pulao" or "pallao" is used to refer to a rice dish in ancient Sanskrit works such as the Yājñavalkya Smṛti.[17] However, according to food writers Colleen Taylor Sen and Charles Perry, and social theorist Ashis Nandy, these references do not substantially correlate to the commonly used meaning and history implied in pilafs, which appear in Indian accounts after the medieval Central Asian conquests.[18][19][20]

Similarly Alexander the Great and his army, many centuries earlier, in the 4th century BCE, have been reported to be so impressed with Bactrian and Sogdian pilavs that his soldiers brought the recipes back to Macedonia when they returned.[21] Similar stories exist of Alexander introducing pilaf to Samarkand; however, they are considered apocryphal by art historian John Boardman.[22] Similarly, it has been reported that pilaf was consumed in the Byzantine Empire and in the Republic of Venice.[23]

The earliest documented recipe for pilaf comes from the tenth-century Persian scholar Avicenna (Ibn Sīnā), who in his books on medical sciences dedicated a whole section to preparing various dishes, including several types of pilaf. In doing so, he described the advantages and disadvantages of every item used for preparing the dish. Accordingly, Persians consider Ibn Sina to be the "father" of modern pilaf.[21] Thirteenth-century Arab texts describe the consistency of pilaf that the grains should be plump and somewhat firm to resemble peppercorns with no mushiness, and each grain should be separate with no clumping.[24]

Another primary source for pilaf dishes comes from the 17th-century Iranian philosopher Molla Sadra.[25]

Pilau became standard fare in the Middle East and Transcaucasia over the years with variations and innovations by the Persians, Arabs, Turks, and Armenians.

During the period of the Soviet Union, the Central Asian versions of the dish spread throughout all Soviet republics, becoming a part of the common Soviet cuisine.

Preparation

[edit]Some cooks prefer to use basmati rice because it is easier to prepare a pilaf where the grains stay "light, fluffy and separate" with this type of rice. However, other types of long-grain rice are also used. The rice is rinsed thoroughly before use to remove the surface starch. Pilaf can be cooked in water or stock. Common additions include fried onions and fragrant spices like cardamom, bay leaves and cinnamon.[24]

Pilaf is usually made with meat or vegetables, but it can also be made plain which is called sade pilav in Turkish, chelo in Persian and ruzz mufalfal in Arabic.[26] On special occasions saffron may be used to give the rice a yellow color. Pilaf is often made by adding the rice to hot fat and stirring briefly before adding the cooking liquid. The fat used varies from recipe to recipe. Cooking methods vary with respect to details such as pre-soaking the rice and steaming after boiling.[24]

Local varieties

[edit]There are thousands of variations of pilaf made with rice or other grains like bulgur.[24] In Central Asia there are plov, pulao on the Indian subcontinent, and variations from Turkmenistan and Turkey. Some include different combinations of meats, fruits or vegetables, while others are simple and served plain.[24] Central Asian, South Asian cuisine, Turkish cuisine, Iranian and Caribbean cuisine are some with distinctive styles of making pilaf.[27]

Afghanistan

[edit]

In Afghan cuisine, Kabuli palaw (Persian : کابلی پلو) is made by cooking basmati with mutton, lamb, beef or chicken, and oil. Kabuli palaw is cooked in large shallow and thick dishes. Fried sliced carrots and raisins are added. Chopped nuts like pistachios, walnuts, or almonds may be added as well. The meat is covered by the rice or buried in the middle of the dish. Kabuli palaw rice with carrots and raisins is very popular in Saudi Arabia, where it is known as roz Bukhari (Arabic: رز بخاري), meaning 'Bukharan rice'.

Armenia

[edit]

Armenians use a lot of bulgur ("cracked wheat") in their pilaf dishes.[28] Armenian recipes may combine vermicelli or orzo with rice cooked in stock seasoned with mint, parsley and allspice.[29] One traditional Armenian pilaf is made with the same noodle rice mixture cooked in stock with raisins, almonds and allspice.[30]

Armenian kinds of rice are discussed by Rose Baboian in her cookbook from 1964 which includes recipes for different pilafs, most rooted in her birthplace of Antep in Turkey.[31] Baboian recommends that the noodles be stir-fried first in chicken fat before being added to the pilaf. Another Armenian cookbook written by Vağinag Pürad recommends to render poultry fat in the oven with red pepper until the fat mixture turns a red color before using the strained fat to prepare pilaf.[31]

Lapa is an Armenian word with several meanings one of which is a "watery boiled rice, thick rice soup, mush" and lepe which refers to various rice dishes differing by region.[32] Antranig Azhderian describes Armenian pilaf as a "dish resembling porridge".[33]

Azerbaijan

[edit]Azerbaijani cuisine includes more than 40 different plov recipes.[34] One of the most reputed dishes is plov from saffron-covered rice, served with various herbs and greens, a combination distinctive from Uzbek plovs. Traditional Azerbaijani plov consists of three distinct components, served simultaneously but on separate platters: rice (warm, never hot), gara (fried beef or chicken pieces with onion, chestnut and dried fruits prepared as an accompaniment to rice), and aromatic herbs. Gara is put on the rice when eating plov, but it is never mixed with rice and the other components. Pilaf is usually called aş in Azerbaijani cuisine.[35]

- Rice pilaf examples from Azerbaijan

-

Azerbaijani shah-pilaf

Bangladesh

[edit]

In Bangladesh, pulao (পোলাও), fulao, or holao, is a popular ceremonial dish cooked only with aromatic rice. Bangladesh cultivates many varieties of aromatic rice which can be found only in this country and some surrounding Indian states with predominantly Bengali populations. Historically, there were many varieties of aromatic rice. These included short grained rice with buttery and other fragrances depending on the variety. Over a long span of time many recipes were lost and then reinvented.

Since the 1970s in Bangladesh pulao has referred to aromatic rice (বাসন্তী পোলাও) "Bashonti polao", first fried either in oil or clarified butter with onions, fresh ginger and whole aromatic spices such as cardamom, cinnamon, black pepper and more depending on each household and region. This is then cooked in stock or water, first boiled and then steamed. It is finished off with a bit more clarified butter, and fragrant essences such as rose water or kewra water. For presentation, beresta (fried onions) are sprinkled on top. Chicken pulao, (morog pulao), is a traditional ceremonial dish among the Bangladeshi Muslim community. There are several different types of morog pulao found only in particular regions or communities.

In Sylhet and Chittagong, a popular ceremonial dish called akhni pulao. Aqni being the rich stock in which mutton is cooked and then used to cook the rice. Another very spicy biryani dish very popular and unique to Bangladesh is called tehari. It is very different in taste to the teharis found in some parts of neighboring India. They are most popularly eaten with beef and chevon (goat meat) but are also paired with chicken.[36] Young small potatoes, mustard oil (which is alternated with clarified butter or oil depending on individual taste), and a unique spice blend found in teharis distinguish them from other meat pulaos. The most famous tehari in the capital city of Dhaka is called Hajir biryani. Although here the name biryani is a misnomer, in usage among the urban young population it differentiates the popular dish mutton biryanis (goat meat).

Brazil

[edit]A significantly modified version of the recipe, often seen as influenced by what is called arroz pilau there, is known in Brazil as arroz de frango desfiado or risoto de frango (Portuguese: [ɐˈʁoz dʒi ˈfɾɐ̃ɡu dʒisfiˈadu], "shredded chicken rice"; [ʁiˈzotu], "chicken risotto"). Rice lightly fried (and optionally seasoned), salted and cooked until soft (but neither soupy nor sticky) in either water or chicken stock is added to chicken stock, onions and sometimes cubed bell peppers (cooked in the stock), shredded chicken breast, green peas, tomato sauce, shoyu, and optionally vegetables (e.g. canned sweet corn, cooked carrot cubes, courgette cubes, broccolini flowers, chopped broccoli or broccolini stalks or leaves fried in garlic seasoning) or herbs (e.g., mint, like in canja) to form a distantly risotto-like dish – but it is generally fluffy (depending on the texture of the rice being added), as generally, once all ingredients are mixed, it is not left to cook longer than five minutes. In the case shredded chicken breast is not added, with the rice being instead served alongside chicken and sauce suprême, it is known as arroz suprême de frango (Portuguese: [ɐˈʁos suˈpɾẽm(i) dʒi ˈfɾɐ̃ɡu], "chicken supreme rice").

Caribbean

[edit]

In the Eastern Caribbean and other Caribbean territories there are variations of pelau which include a wide range of ingredients such as pigeon peas, green peas, green beans, corn, carrots, pumpkin, and meat such as beef or chicken, or cured pig tail. The seasoned meat is usually cooked in a stew, with the rice and other vegetables added afterwards. Coconut milk and spices are also key additions in some islands.

Trinidad is recognized for its pelau, a layered rice with meats and vegetables. It is a mix of traditional African cuisine and "New World" ingredients like ketchup. The process of browning the meat (usually chicken, but also stew beef or lamb) in sugar is an African technique.[37]

In Tobago, pelau is commonly made with crab.[37]

Central Asia

[edit]

Central Asian, e.g. Uzbek, Kyrgyz and Tajik (Uzbek: Osh, Palov, Kyrgyz: Аш, палоо, Tajik: Палов) Kazakh, Turkmen, Karakalpak (Kazakh: Палау, Palaw) or osh differs from other preparations in that rice is not steamed, but instead simmered in a rich stew of meat and vegetables called zirvak (зирвак), until all the liquid is absorbed into the rice. A limited degree of steaming is commonly achieved by covering the pot. It is usually cooked in a kazon (or deghi) over an open fire. The cooking tradition includes many regional and occasional variations.[11][38] Commonly, it is prepared with lamb or beef, browned in lamb fat or oil, and then stewed with fried onions, garlic and carrots. Chicken palov is rare but found in traditional recipes originating in Bukhara. Some regional varieties use distinct types of oil to cook the meat. For example, Samarkand-style plov commonly uses zig'ir oil, a mix of melon seed, cottonseed, sesame seed, and flaxseed oils. Plov is usually simply spiced with salt, peppercorns, and cumin, but coriander, barberries, red pepper, or marigold may be added according to regional variation or the chef's preference. Heads of garlic and chickpeas are sometimes buried into the rice during cooking. Sweet variations with dried apricots, cranberries and raisins are prepared on special occasions.[39]

Although often prepared at home, plov is made on special occasions by an oshpaz or ashpoz (osh/ash master chef), who cooks it over an open flame, sometimes serving up to 1,000 people from a single cauldron on holidays or occasions such as weddings. Oshi nahor, or "morning palov", is served in the early morning (between 6 and 9 am) to large gatherings of guests, typically as part of an ongoing wedding celebration.[40]

Uzbek-style plov is found in the post-Soviet countries and Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China. In Xinjiang, where the dish is known as polu, it is often served with pickled vegetables, including carrots, onion and tomato.[41]

Greece

[edit]

In Greek cuisine, piláfi (πιλάφι) is fluffy and soft, but neither soupy nor sticky, rice that has been boiled in a meat stock or bouillon broth. In Northern Greece, it is considered improper to prepare piláfi on a stovetop; the pot is properly placed in the oven.[citation needed] Gamopílafo ("wedding pilaf") is the prized pilaf served traditionally at weddings and major celebrations in Crete: rice is boiled in lamb or goat broth, then finished with lemon juice. Although it bears the name, Gamopílafo is not a pilaf but rather a kind of risotto, with a creamy and not fluffy texture.

India

[edit]Pulao is usually a mixture of either lentils or vegetables, mainly including peas, potatoes, green beans, carrots or meat, mainly chicken, fish, lamb, goat, pork or prawn with rice. A typical Bengali style pulao is prepared using vegetarian ingredients like Long grain rice or aromatic rice, cashewnut, raisin, saffron, ghee and various spices like nutmeg, bay leaf, cinnamon, cardamom, cumin, clove and mace. There are also a few very elaborate pulaos with Persian names like hazar pasand ("a thousand delights").[42] It is usually served on special occasions and weddings, though it is not uncommon to eat it for a regular lunch or dinner meal. It is considered very high in food energy and fat. A pulao is often complemented with either spiced yogurt or raita.

- Rice pilaf examples from India

-

Pulao Mutton, from West Bengal, India

-

Kashmiri pulao with nuts and fruit

-

Saffron pulao served alongside eggs in gravy

Iran

[edit]

Persian culinary terms referring to rice preparation are numerous and have found their way into the neighbouring languages: polow (rice cooked in broth while the grains remain separate, straining the half cooked rice before adding the broth and then "brewing"), chelow (white rice with separate grains), kateh (sticky rice) and tahchin (slow cooked rice, vegetables, and meat cooked in a specially designed dish). There are also varieties of different rice dishes with vegetables and herbs which are very popular among Iranians.

There are four primary methods of cooking rice in Iran:

- Chelow: rice that is carefully prepared through soaking and parboiling, at which point the water is drained and the rice is steamed. This method results in an exceptionally fluffy rice with the grains separated and not sticky; it also results in a golden rice crust at the bottom of the pot called tahdig (literally "bottom of the pot").

- Polow: rice that is cooked exactly the same as chelo, with the exception that after draining the rice, other ingredients are layered with the rice, and they are then steamed together.

- Kateh: rice that is boiled until the water is absorbed. This is the traditional dish of Northern Iran.

- Damy: cooked almost the same as kateh, except that the heat is reduced just before boiling and a towel is placed between the lid and the pot to prevent steam from escaping. Damy literally means "simmered".

Pakistan

[edit]

In Pakistan, pulao (پلاؤ) is a popular dish cooked with basmati rice cooked in a seasoned meat/bone broth with meat, usually either mutton or beef, and an array of spices including: coriander seeds, cumin, cardamom, cloves and others. As with Afghan cuisine, Kabuli palaw is a staple dish in the western part of the Pakistan, and this style of pulao is often embellished with sliced carrots, almonds and raisins, fried in a sweet syrup. Bannu Beef Pulao, also known as Bannu Gosht Pulao, is a traditional and popular variation of Pulao recipe hailing from the Bannu district of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province in Pakistan. The dish is made with tender beef, aromatic rice, and a blend of local spices, resulting in a rich and robust taste. The beef is first cooked in a separate preparation known as Beef Yakhni, made using a combination of salt, ginger, garlic, onions, and garam masala. This adds an additional depth of flavor to the dish. The beef and rice are then combined, creating a deliciously savory and satisfying dish. This delicacy is often served during special occasions and family dinners and is a staple of the Pashtun culinary tradition. The dish is known for its unique spiciness and beefy flavor, making it a sought-after delicacy among food enthusiasts.[43][44]

Pulao is popular in all parts of Pakistan, but the cooking style can vary slightly in other parts of the country. It is prepared by Sindhi people of Pakistan in their marriage ceremonies, condolence meetings, and other occasions.[45][46]

Levant

[edit]Traditional Levantine cooking includes a variety of Pilaf known as "Maqlubeh", known across the countries of the Eastern Mediterranean. The rice pilaf which is traditionally cooked with meats, eggplants, tomatoes, potatoes, and cauliflower also has a fish variety known as "Sayyadiyeh", or the Fishermen's Dish.

Turkey

[edit]

Historically, mutton stock was the most common cooking liquid for Turkish pilafs, which according to 19th century American sources was called pirinç.[47]

Turkish cuisine contains many different pilaf types. Some of these variations are pirinc (rice) pilaf, bulgur pilaf, and arpa şehriye (orzo) pilaf. Using mainly these three types, Turkish people make many dishes such as perdeli pilav, and etli pilav (rice cooked with cubed beef). Unlike Chinese rice, if Turkish rice is sticky, it is considered unsuccessful. To make the best rice according to Turkish people, one must rinse the rice, cook in butter, then add the water and let it sit until it soaks all the water. This results in a pilaf that is not sticky and every single rice grain falls off of the spoon separately.

Baltics

[edit]Lithuanian pilaf is often referred to as plovas. It tends to consist of rice and vegetables; depending on the region the vegetables can be tomatoes, carrots, cabbage, and/or mushrooms. It often contains chicken pieces or cut-up pieces of pork, usually the meat around the neck or the stomach; seasonings can be heavy or light, and some plovas might be made with rice that is very soft, unlike other variants.

Latvian pilaf is often referred to as plovs or plov. It tends to contain the same ingredients as the Lithuanian plovas and can vary from county to county.

The Greek Orthodox Pontian minority had their own methods of preparing pilav.[48][49][50] Pontians along the Black Sea coast might make pilav with anchovies (called hapsipilavon) or mussels (called mythopilavon).[51][52] Other varieties of Pontian pilav could include chicken,[53] lamb, and vegetables. Typical seasonings are anise, dill, parsley, salt, pepper, and saffron. Some Pontians cooked pine nuts, peanuts, or almonds into their pilav. While pilav was usually made from rice, it could also be made with buckwheat.[54]

Crimea

[edit]Traditional Crimean Tatar pilyav (pilâv) is prepared from rice; meat, onions, or raisins can be added.[55][56]

See also

[edit]- Nasi kebuli, a similar dish from Indonesia

- List of rice dishes

- Bannu pulao

- Fried rice

- Nasi lemak

- Nasi goreng

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Oxford English Dictionary 2006b.

- ^ a b Merriam-Webster Unabridged Dictionary 2019.

- ^ a b Perry 2014, p. 624.

- ^ a b Roger 2000, p. 1144.

- ^ a b c d Roger 2000, p. 1143.

- ^ a b c d Nandy 2004, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d Sengupta 2014, p. 74.

- ^ "Башҡортса пылау (Плов по-башкирски) » Башкирская Кухня" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2023-10-29. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- ^ Gil Marks. Encyclopedia of Jewish Food. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010. ISBN 9780544186316

- ^ Marshall Cavendish. World and Its Peoples. Marshall Cavendish, 2006, p. 662. ISBN 9780761475712

- ^ a b Bruce Kraig, Colleen Taylor Sen. Street Food Around the World: An Encyclopedia of Food and Culture. ABC-CLIO, 2013, p. 384. ISBN 9781598849554.

- ^ Russell Zanca. Life in a Muslim Uzbek Village: Cotton Farming After Communism CSCA. Cengage Learning, 2010, p. 92 92–96. ISBN 9780495092810.

- ^ Desmaisons, Jean J. (1908). Dictionnaire Persan-francais (in French). Brill Archive.

- ^ Vieyra, Antonio, ""Chapter 2. Second part developing the title of this story and inviting the Portuguese to read it [Address to the Portuguese]"", History of the Future, UGA Éditions, pp. 92–100, doi:10.4000/books.ugaeditions.881, retrieved 2024-03-30

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary 2006a.

- ^ "English, v.", Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, 2 March 2023, doi:10.1093/oed/2599967978, retrieved 2024-03-30

- ^ K. T. Achaya (1994). Indian food: a historical companion. Oxford University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-19-562845-6.

- ^ Sen, Colleen Taylor (2014), Feasts and Fasts: A History of Food in India, Reaktion Books, pp. 164–5, ISBN 978-1-78023-391-8 Quote: "(pp. 164–165) "Descriptions of the basic technique appear in thirteenth-century Arab cookbooks, although the name pulao is not used. The word itself is medieval Farsi, and the dish may have been created in the early sixteenth century at the Safavid court in Persia. ... Although dishes combining rice, meat and spices were prepared in ancient times, the technique of first sautéing the rice in ghee and then cooking it slowly to keep the grains separate probably came later with the Mughals."

- ^ Perry, Charles (15 December 1994), "Annual Cookbook Issue : BOOK REVIEW : An Armchair Guide to the Indian Table : INDIAN FOOD: A Historical Companion By K. T. Achaya (Oxford University Press: 1994; $35; 290 pp.)", Los Angeles Times Quote: "The other flaw is more serious. Achaya has clearly read a lot about Indian food, but it was in what historians call secondary sources. In other words, he's mostly reporting what other people have concluded from the primary evidence. Rarely, if ever, does he go to the original data to verify their conclusions. This is a dangerous practice, particularly in India, because certain Indian scholars like to claim that everything in the world originated in India a long time ago. ... Achaya even invents one or two myths of his own. He says there is evidence that south Indians were making pilaf 2,000 years ago, but if you look up the book he footnotes, you find that the Old Tamil word pulavu had nothing to do with pilaf. It meant raw meat or fish."

- ^ Nandy, Ashis (2004), "The Changing Popular Culture of Indian Food: Preliminary Notes", South Asia Research, 24 (1): 9–19, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.830.7136, doi:10.1177/0262728004042760, ISSN 0262-7280, S2CID 143223986 Quote: " (p. 11) Not merely ingredients came to the subcontinent, but also recipes. ... All around India one finds preparations that came originally from outside South Asia. Kebabs came from West and Central Asia and underwent radical metamorphosis in the hot and dusty plains of India. So did biryani and pulao, two rice preparations, usually with meat. Without them, ceremonial dining in many parts of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh is incomplete. Even the term pulao or pilav seems to have come from Arabic and Persian. It is true that in Sanskrit — in the Yajnavalkya Smriti — and in old Tamil, the term pulao occurs (Achaya, 1998b: 11), but it is also true that biryani and pulao today carry mainly the stamp of the Mughal times and its Persianized high culture.

- ^ a b Nabhan, Gary Paul (2014). Cumin, Camels, and Caravans: A Spice Odyssey. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520267206.

- ^ Boardman 2019, p. 102.

- ^ Παναγιωτάκης, Νικόλαος (1998). Ἄνθη χαρίτων: μελετήματα ἑόρτια συγγραφέντα ὑπὸ τῶν ὑποτρόφων τοῦ Ἑλληνικοῦ ἰνστιτούτου βυζαντινῶν καὶ μεταβυζαντινῶν σπουδῶν τῆς Βενετίας... (in Greek). Hellenic Institute of Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Studies in Venice. p. 72. ISBN 978-960-7743-01-5. Archived from the original on 2023-08-27. Retrieved 2023-04-12.

- ^ a b c d e "How to cook perfect pilaf". The Guardian. 26 September 2012. Archived from the original on 2023-03-07. Retrieved 2019-02-13.

- ^ Algat, Ayla (30 July 2013). Classical Turkish Cooking: Traditional Turkish Food for the America. HarperCollins. ISBN 9780062039118.

- ^ Davidson 2014, p. 624.

- ^ Perry, Charles (28 April 1992). "Rice Pilaf: Ingredients, Texture Varies". Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on 2019-02-13. Retrieved 2019-02-13.

- ^ Davidson, Alan (2006). Jaine, Tom (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780192806819.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-280681-9. Archived from the original on 2018-06-03. Retrieved 2018-07-16.

- ^ "Recipe for Armenian-style rice pilaf with vermicelli, peas, and herbs". Boston Globe. 14 January 2014. Archived from the original on 2019-02-14. Retrieved 2019-02-13.

- ^ "Armenian Rice Pilaf With Raisins and Almonds". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2019-02-14. Retrieved 2019-02-13.

- ^ a b Baboian, Rose (1964). Rose Baboian's Armenian-American Cook Book. Archived from the original on 2023-08-27. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ Dankoff, Robert (1995). Armenian Loanwords in Turkish. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 53. ISBN 978-3-447-03640-5.

- ^ Azhderian, Antranig (1898). The Turk and the Land of Haig; Or, Turkey and Armenia: Descriptive, Historical, and Picturesque. Mershon Company. pp. 171–172.

- ^ [/ Азербайджанская кухня] Archived 2009-02-16 at the Wayback Machine, (Azerbaijani Cuisine, Ishyg Publ. House, Baku (in Russian))

- ^ Interview with Jabar Mamedov Archived 2008-12-21 at the Wayback Machine, Head Chef at the "Shirvan Shah" Azerbaijani restaurant in Kyiv, 31 January 2005.

- ^ Long, Lucy M. (2015). Ethnic American Food Today: A Cultural Encyclopedia. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-4422-2731-6. Archived from the original on 2022-07-22. Retrieved 2022-07-22.

- ^ a b Ganeshram, Ramin (31 October 2005). Sweet Hands: Island Cooking from Trinidad & Tobago. Hippocrene Books. ISBN 9780781811255.

- ^ "Uzbek Cuisine Photos: Palov". Archived from the original on 2014-01-04. Retrieved 2013-05-23.

- ^ "chef.rustam - Central Asian, e.g. Tajik and Uzbek (Tajik:..." www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2022-05-15.

- ^ "Perfect Plov Recipe". nargiscafe.com. Archived from the original on 2021-02-27. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- ^ "Going to Xinjiang? Here's What You'll Eat". TripSavvy. Archived from the original on 2022-07-03. Retrieved 2022-05-15.

- ^ Davidson 2014.

- ^ "Home Bannu Beef Pulao Chuburji". www.bannubeefpulaoturabfoods.pk. Archived from the original on 2023-01-22. Retrieved 2023-01-22.

- ^ "Malang Jan Bannu Beef Pulao". niftyfoodz.com. Archived from the original on 2023-01-22. Retrieved 2023-01-22.

- ^ Reejhsinghani, Aroona (2004). Essential Sindhi Cookbook. Penguin Books India. p. 237. ISBN 9780143032014. Archived from the original on 2023-04-15. Retrieved 2015-08-22.

- ^ Reejhsinghani, Aroona (25 July 2013). The Sindhi Kitchen. Westland. ISBN 9789383260171. Retrieved 2015-08-22.

- ^ "Good Housekeeping". 18. 1894.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Five Pontian recipes for Lent". Pontos News (in Greek). 2 March 2014. Archived from the original on 2023-03-07. Retrieved 2021-04-10.

- ^ Voutira, Eftihia (2020). "Genealogies across the cold war divide: The case of the Pontic Greeks from the former Soviet Union and their 'affinal repatriation'". Ethnography. 21 (3): 360. doi:10.1177/1466138120939589. S2CID 221040916. Archived from the original on 2022-09-06. Retrieved 2021-04-10.

- ^ "Sinope Pilaf". Pontos News (in Greek). 7 October 2012. Archived from the original on 2023-03-07. Retrieved 2021-04-10.

- ^ "Mythopilavon: the Pontian mussel pilav". Pontos News (in Greek). 15 February 2013. Archived from the original on 2023-03-07. Retrieved 2021-04-10.

- ^ "Hapsipilavon, the Pontian pilaf with fish". Pontos News (in Greek). 19 February 2021. Archived from the original on 2023-03-07. Retrieved 2021-04-10.

- ^ Charmei, Amber (2018). "Homecoming, Greek-Style". Greece Is. Archived from the original on 2021-04-10. Retrieved 2021-04-10.

- ^ Aglaia Kremezi. "Greece Culinary Travel with Aglaia Kremezi". Epicurious. Archived from the original on 2021-04-10. Retrieved 2021-04-10.

- ^ Qırımtatar yemekleri: Пиляв, 5 January 2023, retrieved 2024-02-10

- ^ Готовим къыймалы пиляв, 20 August 2016, retrieved 2024-02-10

Notes

[edit]- ^ Oxford English Dictionary (subscription required): "A dish, partly of Middle Eastern, partly and ultimately of South Asian origin, consisting of rice (or, in certain areas, wheat) cooked in stock with spices, usually mixed with meat and various other ingredients.[1]

- ^ Merriam-Webster Unabridged Dictionary (subscription required): "rice usually combined with meat and vegetables, fried in oil, steamed in stock, and seasoned with any of numerous herbs (as saffron or cumin)."[2]

- ^ Perry: "A Middle-Eastern method of cooking rice so that every grain remains separate. ...However, there is no evidence that rice was cooked by this technique in India before the Muslim invasions, and Indians themselves associate pilaf-making with Muslim cities such as Hyderabad, Lucknow, and Delhi. .... The first descriptions of the pilaf technique appear in the 13th-century Arabic books Kitab al-Tabikh and Kitab al-Witsla ila al Habib, written in Baghdad and Syria, respectively. They show the technique in its entirety, including the cloth beneath the lid, and describe still-current flavourings such as meat, pulses, and fruit.[3]

- ^ Roger: "As noted, Iranians have a unique method of preparing rice. This method is designed to leave the grains separate and tasty, making the rice fluffy and very flavorful. After soaking, parboiling, and draining, the rice is poured into a dish smeared with melted butter. The lid is then sealed tightly with a cloth and a paste of flour and water. The last stage is to steam it on low heat for about half an hour, after which the rice is removed and fluffed."[4]

- ^ Roger: " (p. 1143) Under the Abbassids, for example (ninth to twelfth century), during the Golden Age of Islam, there was one single empire from Afghanistan to Spain and the North of Arabia. The size of the empire allowed many foods to spread throughout the Middle East. From India, rice went to Syria, Iraq, and Iran, and eventually, it became known and cultivated all the way to Spain. .... Many dishes of that period are still prepared today with ingredients available to the common people. Some of these are vinegar preserves, roasted meat, and cooked livers, which could be bought in the streets, eaten in the shops, or taken home. Such dishes considerably influenced medieval European and Indian cookery;pilaf and meat patties that started out as samosa or sambusak."[5]

- ^ Nandy: "(p. 11) Not merely ingredients came to the subcontinent, but also recipes. ... All around India one finds preparations that came originally from outside South Asia. Kebabs came from West Asia and underwent radical metamorphosis in the hot and dusty plains of India. So did biryani and pulao, two rice preparations, usually with meat. Without them, ceremonial dining in many parts of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh is incomplete. Even the term pulao or pilav seems to have come from Arabic and Persian. It is true that in Sanskrit — in the Yajnavalkya Smriti — and in old Tamil, the term pulao occurs (Achaya, 1998b: 11), but it is also true that biryani and pulao today carry mainly the stamp of the Mughal times and its Persianized high culture."[6]

- ^ Sengupta: "(p. 74) Muslim influence on the style and substance of Indian food was profound. K.T. Achaya writes that the Muslims imported a new refinement and a courtly etiquette of both group and individual dining into the austere dining ambience of Hindu society. ... Babur's son, Humayun, came back to India after spending a long period of exile in Kabul and the Safavid imperial court in Iran. He brought with him an entourage of Persian cooks who introduced the rich and elaborate rice cookery of the Safavid courts to India, combining Indian spices and Persian arts into a rich fusion that became the iconic dish of Islamic Indian cuisine, the biryani."[7]

- ^ Roger: " (p. 1143) Under the Abbassids, for example (ninth to twelfth century), during the Golden Age of Islam, there was one single empire from Afghanistan to Spain and the North of Arabia. The size of the empire allowed many foods to spread throughout the Middle East. From India, rice went to Syria, Iraq, and Iran, and eventually, it became known and cultivated all the way to Spain. .... Many dishes of that period are still prepared today with ingredients available to the common people. Some of these are vinegar preserves, roasted meat, and cooked livers, which could be bought in the streets, eaten in the shops, or taken home. Such dishes considerably influenced medieval European and Indian cookery; for example, paella, which evolved from pulao, and pilaf and meat patties that started out as samosa or sambusak."[5]

- ^ Nandy: "(p. 11) All around India one finds preparations that came originally from outside South Asia. Kebabs came from West and Central Asia and underwent radical metamorphosis in the hot and dusty plains of India. So did biryani and pulao, two rice preparations, usually with meat. Without them, ceremonial dining in many parts of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh is incomplete."[6]

- ^ Sengupta: "(p. 74) Muslim influence on the style and substance of Indian food was profound. K.T. Achaya writes that the Muslims imported a new refinement and a courtly etiquette of both group and individual dining into the austere dining ambience of Hindu society. ... Babur's son, Humayun, came back to India after spending a long period of exile in Kabul and the Safavid imperial court in Iran. He brought with him an entourage of Persian cooks who introduced the rich and elaborate rice cookery of the Safavid courts to India, combining Indian spices and Persian arts into a rich fusion that became the iconic dish of Islamic South Asian cuisine, the biryani."[7]

Bibliography

[edit]- Achaya, K.T. (1994), Indian Food Tradition A Historical Companion, Oxford University Press India, p. 44, ISBN 978-0195628456.

- American Institute for Cancer Research (2005), The New American Plate Cookbook: Recipes for a Healthy Weight and a Healthy Life, University of California Press, pp. 158–, ISBN 978-0-520-24234-0.

- Boardman, John (2019), Alexander the Great: From His Death to the Present Day, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-18175-2.

- Collingham, Elizabeth M. (2007), Curry: A Tale of Cooks and Conquerors, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-532001-5.

- Davidson, Alan (2014), The Oxford Companion to Food, Oxford University Press, pp. 624–625, ISBN 978-0-19-967733-7.

- Kraig, Bruce (2013), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America, Oxford University Press USA, p. 140, ISBN 978-0-19-973496-2.

- Marton, Renee (2014), Rice: A Global History, Reaktion Books, pp. 34–, ISBN 978-1-78023-412-0.

- Merriam-Webster Unabridged Dictionary (2019), pilaf noun, Merriam-Webster Incorporated Unabridged Dictionary; Online, Subscription Required.

- Nabhan, Gary Paul (2014), Cumin, Camels, and Caravans: A Spice Odyssey, Univ of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-26720-6.

- Nandy, Ashis (2004), "The Changing Popular Culture of Indian Food: Preliminary Notes", South Asia Research, 24 (1): 9–19, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.830.7136, doi:10.1177/0262728004042760, ISSN 0262-7280, S2CID 143223986.

- Oxford English Dictionary (2006a), pilaf (n), Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd edition, online (subscription required).

- Oxford English Dictionary (2006b), pilau (n), Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd edition, online (subscription required),

"A dish, partly of Middle Eastern, partly and ultimately of South Asian origin, consisting of rice (or, in certain areas, wheat) cooked in stock with spices, usually mixed with meat and various other ingredients.

- Perry, Charles (2014), "Pilaf", in Jaine, Tom (ed.), The Oxford Companion to Food by Alan Davidson, 3rd Edition, Oxford University Press, pp. 624–625, ISBN 978-0-19-967733-7.

- Perry, Charles (15 December 1994), "Annual Cookbook Issue : BOOK REVIEW : An Armchair Guide to the Indian Table : INDIAN FOOD: A Historical Companion By K. T. Achaya (Oxford University Press: 1994; $35; 290 pp.)", Los Angeles Times.

- Perry, Charles (28 April 1994), "RICE PILAF: INGREDIENTS, TEXTURE VARIES", Los Angeles Times.

- Rasanayagam, C. (1984) [1926], Ancient Jaffna: Being a Research Into the History of Jaffna from Very Early Times to the Portug[u]ese Period, Everyman's Publisher (Madras), pp. 153–4, ISBN 978-81-206-0210-6.

- Roger, Delphine (2000), "The Middle East and South Asia (in Chapter: History and Culture of Food and Drink in Asia)", in Kiple, Kenneth F.; Ornelas, Kriemhild Coneè (eds.), The Cambridge World History of Food, vol. 2, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1140–1150, ISBN 978-0-521-40215-6.

- Sen, Colleen Taylor (2014), Feasts and Fasts: A History of Food in India, Reaktion Books, pp. 164–5, ISBN 978-1-78023-391-8.

- Sengupta, Jayanta (2014), "India", in Freedman, Paul; Chaplin, Joyce E.; Albala, Ken (eds.), Food in Time and Place: The American Historical Association Companion to Food History, Univ of California Press, pp. 68–94, ISBN 978-0-520-27745-8.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of pilaf at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of pilaf at Wiktionary Pulao at the Wikibooks Cookbook subproject

Pulao at the Wikibooks Cookbook subproject Rice Pilaf at the Wikibooks Cookbook subproject

Rice Pilaf at the Wikibooks Cookbook subproject Kashmiri Pulao at the Wikibooks Cookbook subproject

Kashmiri Pulao at the Wikibooks Cookbook subproject

- Ancient dishes

- Rice dishes

- African cuisine

- Armenian cuisine

- Balkan cuisine

- Caucasian cuisine

- Central Asian cuisine

- French cuisine

- Iranian cuisine

- Iraqi cuisine

- Israeli cuisine

- Jewish cuisine

- Kazakh cuisine

- Kyrgyz cuisine

- Kurdish cuisine

- Latin American cuisine

- Latvian cuisine

- Lithuanian cuisine

- Middle Eastern cuisine

- Ottoman cuisine

- Pakistani rice dishes

- South Asian cuisine

- Fijian cuisine

- Soviet cuisine

- Tajik cuisine

- Turkmen cuisine

- Uzbek dishes

- Pontic Greek cuisine

- Romani cuisine

- World cuisine

- Types of food

- Street food

- Indian rice dishes

- Azerbaijani cuisine