Nabilone

| |

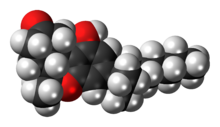

Top: (R,R)-(−)-nabilone, Center: (S,S)-(+)-nabilone, Bottom: Space-filling model of (R,R)-(−)-nabilone | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Cesamet, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a607048 |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Cannabinoid |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 20% after first-pass by the liver |

| Protein binding | similar to THC (±97%) |

| Elimination half-life | 2 hours, with metabolites around 35 hours |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.164.824 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C24H36O3 |

| Molar mass | 372.549 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Nabilone, sold under the brand name Cesamet among others, is a synthetic cannabinoid with therapeutic use as an antiemetic and as an adjunct analgesic for neuropathic pain.[1][2] It mimics tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the primary psychoactive compound found naturally occurring in Cannabis.[3]

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States has indicated nabilone for chemotherapy-induced nausea/vomiting. In other countries, such as Canada, it is widely used as an adjunct therapy for chronic pain management. Numerous trials and case studies have demonstrated modest effectiveness for relieving fibromyalgia[4] and multiple sclerosis.[5][6]

Medical uses

[edit]Nabilone is used to treat nausea and vomiting in people under chemotherapy.[3][7]

Nabilone has shown modest effectiveness in relieving fibromyalgia.[4] A 2011 systematic review of cannabinoids for chronic pain determined there was evidence of safety and modest efficacy for some conditions.[8]

The main settings that have seen published clinical trials of nabilone include movement disorders such as parkinsonism, chronic pain, dystonia and spasticity neurological disorders, multiple sclerosis, and the nausea of cancer chemotherapy. Nabilone is also effective in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease, especially ulcerative colitis.

In one study of current daily users of cannabis, oral nabilone at 4, 6, and 8 mg produced sustained and dose-dependent mood elevation and psychomotor slowing comparable to 10 or 20 mg oral dronabinol (THC). Nabilone had a slower onset of peak action and a greater dose-dependence of effects, which the investigators attributed to greater bioavailability. [9]

A study comparing nabilone with metoclopramide, conducted before the development of modern 5-HT3 antagonist anti-emetics such as ondansetron, revealed that patients taking cisplatin chemotherapy preferred metoclopramide, while patients taking carboplatin preferred nabilone to control nausea and vomiting.[10][11]

Nabilone is sometimes used for nightmares in post-traumatic stress disorder, but there have not been studies longer than nine weeks, so effects of longer-term use are not known.[12] Nabilone has also been used for medication overuse headache.[13]

Side effects

[edit]Nabilone can increase – rather than decrease – postoperative pain.[citation needed] In the treatment of fibromyalgia, adverse effects limit the useful dose.[4] Adverse effects of nabilone include, but are not limited to: dizziness/vertigo, euphoria, drowsiness, dry mouth, ataxia, sleep disturbance, headache, nausea, disorientation, depersonalization, hallucinations, and asthenia.[3]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]Nabilone is a partial agonist of the cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors.[14][15]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Nabilone is given in 1 or 2 mg doses multiple times a day up to a total of 6 mg. It is completely absorbed from oral administration and highly plasma protein bound. Multiple cytochrome P450 enzymes extensively metabolize nabilone to various metabolites that have not been fully characterized.[3]

Chemistry

[edit]Nabilone is a racemic mixture consisting of (S,S)-(+)- and (R,R)-(−)-isomers.

History

[edit]Nabilone was originally developed by Eli Lilly and Company; and was first approved by Health Canada in 1981;[16][17] shortly followed by its approval in Mexico, the United Kingdom, and Germany. Lilly received FDA approval in 1985 to market it, but withdrew that approval in 1989 for commercial reasons.[18] Valeant Pharmaceuticals acquired the rights from Lilly in 2004.[18] Valeant tried and failed to get the medication approved by the FDA again in 2005[19] and then succeeded in 2006.[18]

In 2007, Valeant acquired the United Kingdom and European Union rights to market nabilone from Cambridge Laboratories.[20]

Nabilone was approved in Austria to treat chemotherapy-induced nausea in 2013; it was already approved in Spain for the same indication and was legal in Belgium to treat glaucoma, spasticity in multiple sclerosis, wasting due to AIDS, and chronic pain.[21]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Nabilone - AdisInsight".

- ^ "Nabilone Advanced Patient Information".

- ^ a b c d "Nabilone label" (PDF). FDA. May 2006.

- ^ a b c Fine PG, Rosenfeld MJ (2013). "The endocannabinoid system, cannabinoids, and pain". Rambam Maimonides Medical Journal (Review). 4 (4): e0022. doi:10.5041/RMMJ.10129. PMC 3820295. PMID 24228165.

- ^ Wissel J, Haydn T, Müller J, Brenneis C, Berger T, Poewe W, Schelosky LD (October 2006). "Low dose treatment with the synthetic cannabinoid Nabilone significantly reduces spasticity-related pain : a double-blind placebo-controlled cross-over trial". Journal of Neurology (Research article). 253 (10): 1337–41. doi:10.1007/s00415-006-0218-8. PMID 16988792. S2CID 24206300.

- ^ Nielsen S, Germanos R, Weier M, Pollard J, Degenhardt L, Hall W, Buckley N, Farrell M (February 2018). "The Use of Cannabis and Cannabinoids in Treating Symptoms of Multiple Sclerosis: a Systematic Review of Reviews". Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 18 (2): 8. doi:10.1007/s11910-018-0814-x. hdl:2123/18910. PMID 29442178. S2CID 3375801.

- ^ "Nabilone Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) - (eMC)". UK Electronic Medicines Compendium. August 2014. Archived from the original on 2017-12-22. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- ^ Lynch ME, Campbell F (November 2011). "Cannabinoids for treatment of chronic non-cancer pain; a systematic review of randomized trials". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 72 (5): 735–44. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03970.x. PMC 3243008. PMID 21426373.

- ^ Bedi G, Cooper ZD, Haney M (September 2013). "Subjective, cognitive and cardiovascular dose-effect profile of nabilone and dronabinol in marijuana smokers". Addiction Biology. 18 (5): 872–81. doi:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00427.x. PMC 3335956. PMID 22260337.

- ^ Cunningham D, Bradley CJ, Forrest GJ, Hutcheon AW, Adams L, Sneddon M, Harding M, Kerr DJ, Soukop M, Kaye SB (April 1988). "A randomized trial of oral nabilone and prochlorperazine compared to intravenous metoclopramide and dexamethasone in the treatment of nausea and vomiting induced by chemotherapy regimens containing cisplatin or cisplatin analogues". European Journal of Cancer & Clinical Oncology (Randomized controlled trial). 24 (4): 685–9. doi:10.1016/0277-5379(88)90300-8. PMID 2838294.

- ^ Smith LA, Azariah F, Lavender VT, Stoner NS, Bettiol S (November 2015). "Cannabinoids for nausea and vomiting in adults with cancer receiving chemotherapy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (11): CD009464. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009464.pub2. PMC 6931414. PMID 26561338.

- ^ "Long-term Nabilone Use: A Review of the Clinical Effectiveness and Safety". CADTH Rapid Response Reports. Oct 2015. PMID 26561692.

- ^ Pini LA, Guerzoni S, Cainazzo MM, Ferrari A, Sarchielli P, Tiraferri I, Ciccarese M, Zappaterra M (November 2012). "Nabilone for the treatment of medication overuse headache: results of a preliminary double-blind, active-controlled, randomized trial". The Journal of Headache and Pain. 13 (8): 677–84. doi:10.1007/s10194-012-0490-1. PMC 3484259. PMID 23070400.

- ^ Sholler DJ, Huestis MA, Amendolara B, Vandrey R, Cooper ZD (December 2020). "Therapeutic potential and safety considerations for the clinical use of synthetic cannabinoids". Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 199: 173059. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2020.173059. PMC 7725960. PMID 33086126.

- ^ Zhornitsky S, Pelletier J, Assaf R, Giroux S, Li CR, Potvin S (January 2021). "Acute effects of partial CB1 receptor agonists on cognition - A meta-analysis of human studies". Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 104: 110063. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110063. PMID 32791166. S2CID 221092170.

- ^ Lutge EE, Gray A, Siegfried N (April 2013). "The medical use of cannabis for reducing morbidity and mortality in patients with HIV/AIDS". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD005175. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005175.pub3. PMID 23633327.

- ^ "Nabilone". Health Canada. Retrieved 2023-07-01.

- ^ a b c "Valeant returns synthetic cannabinoid to USA". Pharma Times. 17 May 2006.

- ^ "FDA turns down Valeant's anti-nausea drug". Pharma Times. 3 January 2006.

- ^ "Cambridge Labs divests nabilone to Valeant - Pharmaceutical industry n". The Pharma Letter. February 27, 2007.

- ^ "Cannabis Laws & Scheduling in Europe - MedicalMarijuana.eu". MedicalMarijuana.eu. Archived from the original on 18 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.