Noscapine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Narcotine, nectodon, nospen, anarcotine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ~30% |

| Elimination half-life | 1.5–4 h (mean 2.5 h) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.004.455 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C22H23NO7 |

| Molar mass | 413.426 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

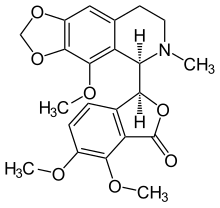

Noscapine, also known as narcotine, nectodon, nospen, anarcotine and (archaic) opiane, is a benzylisoquinoline alkaloid of the phthalideisoquinoline structural subgroup, which has been isolated from numerous species of the family Papaveraceae (poppy family). It lacks effects associated with opioids such as sedation, euphoria, or analgesia (pain-relief) and lacks addictive potential.[1] Noscapine is primarily used for its antitussive (cough-suppressing) effects.

Medical uses

[edit]Noscapine is often used as an antitussive medication.[2] A 2012 Dutch guideline, however, does not recommend its use for acute coughing.[3]

Side effects

[edit]- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Loss of coordination

- Hallucinations (auditory and visual)

- Loss of sexual drive

- Swelling of prostate

- Loss of appetite

- Dilated pupils

- Increased heart rate

- Shaking and muscle spasms

- Chest pain

- Increased alertness

- Increased wakefulness

- Loss of stereoscopic vision

Interactions

[edit]Noscapine can increase the effects of centrally sedating substances such as alcohol and hypnotics.[4]

The drug should not be taken with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), as unknown and potentially fatal effects may occur.[citation needed]

Noscapine should not be taken in conjunction with warfarin as the anticoagulant effects of warfarin may be increased.[5]

Biosynthesis

[edit]

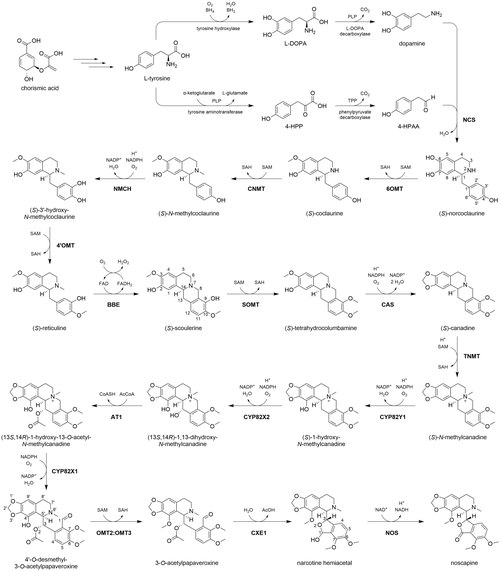

The biosynthesis of noscapine in P. somniferum begins with chorismic acid, which is synthesized via the shikimate pathway from erythrose 4-phosphate and phosphoenolpyruvate. Chorismic acid is a precursor to the amino acid tyrosine, the source of nitrogen in benzylisoquinoline alkaloids. Tyrosine can undergo a PLP-mediated transamination to form 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvic acid (4-HPP), followed by a TPP-mediated decarboxylation to form 4-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (4-HPAA). Tyrosine can also be hydroxylated to form 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA), followed by a PLP-mediated decarboxylation to form dopamine. Norcoclaurine synthase (NCS) catalyzes a Pictet-Spengler reaction between 4-HPAA and dopamine to synthesize (S)-norcoclaurine, providing the characteristic benzylisoquinoline scaffold. (S)-Norcoclaurine is sequentially 6-O-methylated (6OMT), N-methylated (CNMT), 3-hydroxylated (NMCH), and 4′-O-methylated (4′OMT), with the use of cofactors S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM) and NADP+ for methylations and hydroxylations, respectively. These reactions produce (S)-reticuline, a key branchpoint intermediate in the biosynthesis of benzylisoquinoline alkaloids.[6]

The remainder of the noscapine biosynthetic pathway is largely governed by a single biosynthetic 10-gene cluster.[7] Genes comprising the cluster encode enzymes responsible for nine of the eleven remaining chemical transformations. First, berberine bridge enzyme (BBE), an enzyme not encoded by the cluster, forms the fused four-ring structure in (S)-scoulerine. BBE uses O2 as an oxidant and is aided by cofactor flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD). Next, an O-methyltransferase (SOMT) methylates the 9-hydroxyl group. Canadine synthase (CAS) catalyzes the formation of a unique C2-C3 methylenedioxy bridge in (S)-canadine.[8] An N-methylation (TNMT) and two hydroxylations (CYP82Y1, CYP82X2) follow, aided by SAM and O2/NADPH, respectively. The C13 alcohol is then acetylated by an acetyltransferase (AT1) using acetyl-CoA. Another cytochrome P450 enzyme (CYP82X1) catalyzes the hydroxylation of C8, and the newly formed hemiaminal spontaneously cleaves, yielding a tertiary amine and aldehyde. A methyltransferase heterodimer (OMT2:OMT3) catalyzes a SAM-mediated O-methylation on C4′.[9] The O-acetyl group is then cleaved by a carboxylesterase (CXE1), yielding an alcohol which immediately reacts with the neighboring C1 aldehyde to form a hemiacetal in a new five-membered ring. The apparent counteractivity between AT1 and CXE1 suggests that acetylation in this context is employed as a protective group, preventing hemiacetal formation until the ester is enzymatically cleaved.[10] Finally, an NAD+-dependent short-chain dehydrogenase (NOS) oxidizes the hemiacetal to a lactone, completing noscapine biosynthesis.[6]

Mechanism of action

[edit]Noscapine's antitussive effects appear to be primarily mediated by its σ–receptor agonist activity. Evidence for this mechanism is suggested by experimental evidence in rats. Pretreatment with rimcazole, a σ-specific antagonist, causes a dose-dependent reduction in antitussive activity of noscapine.[11] Noscapine, and its synthetic derivatives called noscapinoids, are known to interact with microtubules and inhibit cancer cell proliferation [12]

Structure analysis

[edit]The lactone ring is unstable and opens in basic media. The opposite reaction is presented in acidic media. The bond (C1−C3′) connecting the two optically active carbon atoms is also unstable. In aqueous solution of sulfuric acid and heating it dissociates into cotarnine (4-methoxy-6-methyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-[1,3]dioxolo[4,5-g]isoquinoline) and opic acid (6-formyl-2,3-dimethoxybenzoic acid). When noscapine is reduced with zinc/HCl, the bond C1−C3′ saturates and the molecule dissociates into hydrocotarnine (2-hydroxycotarnine) and meconine (6,7-dimethoxyisobenzofuran-1(3H)-one).

History

[edit]Noscapine was first isolated and characterized in chemical breakdown and properties in 1803 under the denomination of "Narcotine"[13][14] by Jean-Francois Derosne, a French chemist in Paris. Then Pierre-Jean Robiquet, another French chemist, proved narcotine and morphine to be distinct alkaloids in 1831.[15] Finally, Pierre-Jean Robiquet conducted over 20 years between 1815 and 1835 a series of studies in the enhancement of methods for the isolation of morphine, and also isolated in 1832 another very important component of raw opium, that he called codeine, currently a widely used opium-derived compound.

Society and culture

[edit]Recreational use

[edit]There are anecdotal reports of the recreational use of over-the-counter drugs in several countries,[16] being readily available from local pharmacies without a prescription. The effects, beginning around 45 to 120 minutes after consumption, are similar to dextromethorphan and alcohol intoxication. Unlike dextromethorphan, noscapine is not an NMDA receptor antagonist.[17]

Noscapine in heroin

[edit]Noscapine can survive the manufacturing processes of heroin and can be found in street heroin. This is useful for law enforcement agencies, as the amounts of contaminants can identify the source of seized drugs. In 2005 in Liège, Belgium, the average noscapine concentration was around 8%.[18]

Noscapine has also been used to identify drug users who are taking street heroin at the same time as prescribed diamorphine.[19] Since the diamorphine in street heroin is the same as the pharmaceutical diamorphine, examination of the contaminants is the only way to test whether street heroin has been used. Other contaminants used in urine samples alongside noscapine include papaverine and acetylcodeine. Noscapine is metabolised by the body, and is itself rarely found in urine, instead being present as the primary metabolites, cotarnine and meconine. Detection is performed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry or liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LCMS) but can also use a variety of other analytical techniques.

Research

[edit]Clinical Trials

[edit]The efficacy of noscapine in the treatment of certain hematological malignancies has been explored in the clinic.[20][21] Polyploidy induction by noscapine has been observed in vitro in human lymphocytes at high dose levels (>30 μM); however, low-level systemic exposure, e.g. with cough medications, does not appear to present a genotoxic hazard. The mechanism of polyploidy induction by noscapine is suggested to involve either chromosome spindle apparatus damage or cell fusion.[22][23]

Noscapine Biosynthesis Reconstitution

[edit]Many of the enzymes in the noscapine biosynthetic pathway was elucidated by the discovery of a 10 gene "operon-like cluster" named HN1.[7] In 2016, the biosynthetic pathway of noscapine was reconstituted in yeast cells,[24] allowing the drug to be synthesised without the requirement of harvest and purification from plant material. In 2018, the entire noscapine pathway was reconstituted and produced in yeast from simple molecules. In addition, protein expression was optimised in yeast, allowing production of noscapine to be improved 18,000 fold.[25] It is hoped that this technology could be used to produce pharmaceutical alkaloids such as noscapine which are currently expressed at too low a yield in plantae to be mass-produced, allowing them to become marketable therapeutic drugs.[26]

Anticancer derivatives

[edit]Noscapine is itself an antimitotic agent, therefore its analogs have great potential as novel anti-cancer drugs.[27] Analogs having significant cytotoxic effects through modified 1,3-benzodioxole moiety have been developed.[28] Similarly, N-alkyl amine, 1,3-diynyl, 9-vinyl-phenyl and 9-arylimino derivatives of noscapine have also been developed.[29][30][31][32] Their mechanism of action is through tubulin inhibition.[33]

Anti-Inflammatory Effects

[edit]Interestingly, various studies have indicated that noscapine has anti-inflammatory effects and significantly reduces the levels of proinflammatory factors such as interleukin 1β (IL-1β), IFN-c, and IL-6. In this regard, in another study, Khakpour et al. examined the effect of noscapine against carrageenan-induced inflammation in rats. They found that noscapine at a dose of 5 mg/kg body weight in three hours after the injection has the most anti-inflammatory effects. Moreover, they showed that the amount of inflammation reduction at this dose of noscapine is approximately equal to indomethacin, a standard anti-inflammatory medication. Furthermore, Shiri et al. concluded that noscapine prevented the progression of bradykinin-induced inflammation in the rat's foot by antagonising bradykinin receptors. In addition, Zughaier et al. evaluated the anti-inflammatory effects of brominated noscapine. The brominated form of noscapine has been shown to inhibit the secretion of the cytokine TNF-α and the chemokine CXCL10 from macrophages, thereby reducing inflammation without affecting macrophage survival. Furthermore, the bromated derivative of noscapine has about 5 to 40 times more potent effects than noscapine. Again, this brominated derivative also inhibits toll-like receptors (TLR), TNF-α, and nitric oxide (NO) in human and mouse macrophages without causing toxicity. Furthermore, brominated noscapine has potent anti-inflammatory activity in models of septic inflammation, inhibits inflammatory factors in a dose-dependent manner, and prevents the release of TNF-α and NO in human and mouse macrophages.[34]

See also

[edit]- Cough syrup

- Codeine; Pholcodine

- Dextromethorphan; Dimemorfan

- Racemorphan; Dextrorphan; Levorphanol

- Butamirate

- Pentoxyverine

- Tipepidine

- Cloperastine

- Levocloperastine

- Narceine, a related opium alkaloid.

References

[edit]- ^ Altinoz MA, Topcu G, Hacimuftuoglu A, Ozpinar A, Ozpinar A, Hacker E, Elmaci İ (August 2019). "Noscapine, a Non-addictive Opioid and Microtubule-Inhibitor in Potential Treatment of Glioblastoma". Neurochemical Research. 44 (8): 1796–1806. doi:10.1007/s11064-019-02837-x. PMID 31292803. S2CID 195873326.

- ^ Singh H, Singh P, Kumari K, Chandra A, Dass SK, Chandra R (March 2013). "A review on noscapine, and its impact on heme metabolism". Current Drug Metabolism. 14 (3): 351–360. doi:10.2174/1389200211314030010. PMID 22935070.

- ^ Verlee L, Verheij TJ, Hopstaken RM, Prins JM, Salomé PL, Bindels PJ (2012). "[Summary of NHG practice guideline 'Acute cough']". Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde. 156: A4188. PMID 22917039.

- ^ Jasek, W, ed. (2007). Austria-Codex (in German) (2007/2008 ed.). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. ISBN 978-3-85200-181-4.

- ^ Ohlsson S, Holm L, Myrberg O, Sundström A, Yue QY (February 2008). "Noscapine may increase the effect of warfarin". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 65 (2): 277–278. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.03018.x. PMC 2291222. PMID 17875192.

- ^ a b Singh A, Menéndez-Perdomo IM, Facchini PJ (2019). "Benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis in opium poppy: an update". Phytochemistry Reviews. 18 (6): 1457–1482. Bibcode:2019PChRv..18.1457S. doi:10.1007/s11101-019-09644-w. S2CID 208301912.

- ^ a b Winzer T, Gazda V, He Z, Kaminski F, Kern M, Larson TR, et al. (June 2012). "A Papaver somniferum 10-gene cluster for synthesis of the anticancer alkaloid noscapine". Science. 336 (6089): 1704–1708. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1704W. doi:10.1126/science.1220757. PMID 22653730. S2CID 41420733.

- ^ Dang TT, Facchini PJ (January 2014). "Cloning and characterization of canadine synthase involved in noscapine biosynthesis in opium poppy". FEBS Letters. 588 (1): 198–204. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2013.11.037. PMID 24316226. S2CID 26504234.

- ^ Park MR, Chen X, Lang DE, Ng KK, Facchini PJ (July 2018). "Heterodimeric O-methyltransferases involved in the biosynthesis of noscapine in opium poppy". The Plant Journal. 95 (2): 252–267. doi:10.1111/tpj.13947. PMID 29723437. S2CID 19237801.

- ^ Dang TT, Chen X, Facchini PJ (February 2015). "Acetylation serves as a protective group in noscapine biosynthesis in opium poppy". Nature Chemical Biology. 11 (2): 104–106. doi:10.1038/nchembio.1717. PMID 25485687.

- ^ Kamei J (1996). "Role of opioidergic and serotonergic mechanisms in cough and antitussives". Pulmonary Pharmacology. 9 (5–6): 349–356. doi:10.1006/pulp.1996.0046. PMID 9232674.

- ^ Lopus M, Naik PK (February 2015). "Taking aim at a dynamic target: Noscapinoids as microtubule-targeted cancer therapeutics". Pharmacological Reports. 67 (1): 56–62. doi:10.1016/j.pharep.2014.09.003. PMID 25560576. S2CID 19622488.

- ^ Derosne JF (1803). "Mémoire sur l'opium". Annales de chimie. 11: 257–285.

- ^ Drobnik J, Drobnik E (December 2016). "Timeline and bibliography of early isolations of plant metabolites (1770-1820) and their impact to pharmacy: A critical study". Fitoterapia. 115: 155–164. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2016.10.009. PMID 27984164.

- ^ Wisniak J (March 2013). "Pierre-Jean Robiquet". Educación Química. 24 (Supplement 1): 139–149. doi:10.1016/S0187-893X(13)72507-2.

- ^ Bhatia M, Vaid L (August 2004). "Type of drug abuse in patients with psychogenic cough". The Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 118 (8): 659–660. doi:10.1258/0022215041917844. PMID 15453951.

- ^ Church J, Jones MG, Davies SN, Lodge D (June 1989). "Antitussive agents as N-methylaspartate antagonists: further studies". Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 67 (6): 561–567. doi:10.1139/y89-090. PMID 2673498.

- ^ Denooz R, Dubois N, Charlier C (September 2005). "[Analysis of two year heroin seizures in the Liege area]". Revue Médicale de Liège (in French). 60 (9): 724–728. PMID 16265967.

- ^ Paterson S, Lintzeris N, Mitchell TB, Cordero R, Nestor L, Strang J (December 2005). "Validation of techniques to detect illicit heroin use in patients prescribed pharmaceutical heroin for the management of opioid dependence". Addiction. 100 (12): 1832–1839. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01225.x. PMID 16367984.

- ^ "Study of Noscapine for Patients With Low Grade Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma or Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Refractory to Chemotherapy". ClinicalTrials.gov. May 22, 2014.

- ^ "A Study of Noscapine HCl (CB3304) in Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma". ClinicalTrials.gov. October 7, 2016.

- ^ Mitchell ID, Carlton JB, Chan MY, Robinson A, Sunderland J (November 1991). "Noscapine-induced polyploidy in vitro". Mutagenesis. 6 (6): 479–486. doi:10.1093/mutage/6.6.479. PMID 1800895.

- ^ Schuler M, Muehlbauer P, Guzzie P, Eastmond DA (January 1999). "Noscapine hydrochloride disrupts the mitotic spindle in mammalian cells and induces aneuploidy as well as polyploidy in cultured human lymphocytes". Mutagenesis. 14 (1): 51–56. doi:10.1093/mutage/14.1.51. PMID 10474821.

- ^ Li Y, Smolke CD (July 2016). "Engineering biosynthesis of the anticancer alkaloid noscapine in yeast". Nature Communications. 7: 12137. Bibcode:2016NatCo...712137L. doi:10.1038/ncomms12137. PMC 4935968. PMID 27378283.

- ^ Li Y, Li S, Thodey K, Trenchard I, Cravens A, Smolke CD (April 2018). "Complete biosynthesis of noscapine and halogenated alkaloids in yeast". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 115 (17): E3922–E3931. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115E3922L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1721469115. PMC 5924921. PMID 29610307.

- ^ Kries H, O'Connor SE (April 2016). "Biocatalysts from alkaloid producing plants". Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 31: 22–30. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.12.006. hdl:21.11116/0000-0002-B92F-A. PMID 26773811.

- ^ Mahmoudian M, Rahimi-Moghaddam P (January 2009). "The anti-cancer activity of noscapine: a review". Recent Patents on Anti-Cancer Drug Discovery. 4 (1): 92–97. doi:10.2174/157489209787002524. PMID 19149691.

- ^ Yong C, Devine SM, Abel AC, Tomlins SD, Muthiah D, Gao X, et al. (September 2021). "1,3-Benzodioxole-Modified Noscapine Analogues: Synthesis, Antiproliferative Activity, and Tubulin-Bound Structure". ChemMedChem. 16 (18): 2882–2894. doi:10.1002/cmdc.202100363. PMID 34159741. S2CID 235610355.

- ^ Dash SG, Suri C, Nagireddy PK, Kantevari S, Naik PK (September 2021). "Rational design of 9-vinyl-phenyl noscapine as potent tubulin binding anticancer agent and evaluation of the effects of its combination on Docetaxel". Journal of Biomolecular Structure & Dynamics. 39 (14): 5276–5289. doi:10.1080/07391102.2020.1785945. PMID 32608323. S2CID 220283865.

- ^ Meher RK, Pragyandipta P, Pedapati RK, Nagireddy PK, Kantevari S, Nayek AK, Naik PK (September 2021). "Rational design of novel N-alkyl amine analogues of noscapine, their chemical synthesis and cellular activity as potent anticancer agents". Chemical Biology & Drug Design. 98 (3): 445–465. doi:10.1111/cbdd.13901. PMID 34051055. S2CID 235243148.

- ^ Patel AK, Meher RK, Reddy PK, Pedapati RK, Pragyandipta P, Kantevari S, et al. (July 2021). "Rational design, chemical synthesis and cellular evaluation of novel 1,3-diynyl derivatives of noscapine as potent tubulin binding anticancer agents". Journal of Molecular Graphics & Modelling. 106: 107933. doi:10.1016/j.jmgm.2021.107933. PMID 33991960. S2CID 234683080.

- ^ Patel AK, Meher RK, Nagireddy PK, Pragyandipta P, Pedapati RK, Kantevari S, Naik PK (April 2021). "9-Arylimino noscapinoids as potent tubulin binding anticancer agent: chemical synthesis and cellular evaluation against breast tumour cells". SAR and QSAR in Environmental Research. 32 (4): 269–291. doi:10.1080/1062936X.2021.1891567. PMID 33687299. S2CID 232161419.

- ^ Mandavi S, Verma SK, Banjare L, Dubey A, Bhatt R, Thareja S, Jain AK (2021). "A Comprehension into Target Binding and Spatial Fingerprints of Noscapinoid Analogues as Inhibitors of Tubulin". Medicinal Chemistry. 17 (6): 611–622. doi:10.2174/1573406416666200117120348. PMID 31951171. S2CID 210701250.

- ^ Rahmanian-Devin P, Baradaran Rahimi V, Jaafari MR, Golmohammadzadeh S, Sanei-Far Z, Askari VR (2021-11-30). "Noscapine, an Emerging Medication for Different Diseases: A Mechanistic Review". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2021: 8402517. doi:10.1155/2021/8402517. PMC 8648453. PMID 34880922.