Chemical weapon

Pallets of 155 mm artillery shells containing "HD" (mustard gas) at Pueblo Depot Activity (PUDA) chemical weapons storage facility | |

| Blister agents | |

|---|---|

| Phosgene oxime | (CX) |

| Lewisite | (L) |

| Mustard gas (Yperite) | (HD) |

| Nitrogen mustard | (HN) |

| Nerve agents | |

| Tabun | (GA) |

| Sarin | (GB) |

| Soman | (GD) |

| Cyclosarin | (GF) |

| VX | (VX) |

| Blood agents | |

| Cyanogen chloride | (CK) |

| Hydrogen cyanide | (AC) |

| Choking agents | |

| Chloropicrin | (PS) |

| Phosgene | (CG) |

| Diphosgene | (DP) |

| Chlorine | (CI) |

| Vomiting agents | |

| Adamsite | (DM) |

| |

| Soviet chemical weapons canister from an Albanian stockpile[1] | |

| Part of a series on | |||

| Chemical agents | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lethal agents | |||

| Incapacitating agents | |||

|

|||

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be any chemical compound intended as a weapon "or its precursor that can cause death, injury, temporary incapacitation or sensory irritation through its chemical action. Munitions or other delivery devices designed to deliver chemical weapons, whether filled or unfilled, are also considered weapons themselves."[2]

Chemical weapons are classified as weapons of mass destruction (WMD), though they are distinct from nuclear weapons, biological weapons, and radiological weapons. All may be used in warfare and are known by the military acronym NBC (for nuclear, biological, and chemical warfare). Weapons of mass destruction are distinct from conventional weapons, which are primarily effective due to their explosive, kinetic, or incendiary potential. Chemical weapons can be widely dispersed in gas, liquid and solid forms, and may easily afflict others than the intended targets. Nerve gas, tear gas, and pepper spray are three modern examples of chemical weapons.[3]

Lethal unitary chemical agents and munitions are extremely volatile and they constitute a class of hazardous chemical weapons that have been stockpiled by many nations. Unitary agents are effective on their own and do not require mixing with other agents. The most dangerous of these are nerve agents (GA, GB, GD, and VX) and vesicant (blister) agents, which include formulations of sulfur mustard such as H, HT, and HD. They all are liquids at normal room temperature, but become gaseous when released. Widely used during the World War I, the effects of so-called mustard gas, phosgene gas, and others caused lung searing, blindness, death and maiming.

During World War II the Nazi regime used a commercial hydrogen cyanide blood agent trade-named Zyklon B to commit industrialised genocide against Jews and other targeted populations in large gas chambers.[4] The Holocaust resulted in the largest death toll to chemical weapons in history.[5]

As of 2016[update], CS gas and pepper spray remain in common use for policing and riot control; CS and pepper spray are considered non-lethal weapons. Under the Chemical Weapons Convention (1993), there is a legally binding, worldwide ban on the production, stockpiling, and use of chemical weapons and their precursors. However, large stockpiles of chemical weapons continue to exist, usually justified as a precaution against possible use by an aggressor. Continued storage of these chemical weapons is a hazard, as many of the weapons are now more than 50 years old, raising risks significantly.[6][7]

Use

[edit]Chemical warfare involves using the toxic properties of chemical substances as weapons. This type of warfare is distinct from nuclear warfare and biological warfare, which together make up NBC, the military initialism for Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical (warfare or weapons). None of these fall under the term conventional weapons, which are primarily effective because of their destructive potential. Chemical warfare does not depend upon explosive force to achieve an objective. It depends upon the unique properties of the chemical agent weaponized.

A lethal agent is designed to injure, incapacitate, or kill an opposing force, or deny unhindered use of a particular area of terrain. Defoliants are used to quickly kill vegetation and deny its use for cover and concealment. Chemical warfare can also be used against agriculture and livestock to promote hunger and starvation. Chemical payloads can be delivered by remote controlled container release, aircraft, or rocket. Protection against chemical weapons includes proper equipment, training, and decontamination measures.

History

[edit]

Simple chemical weapons were used sporadically throughout antiquity and into the Industrial age.[8] It was not until the 19th century that the modern conception of chemical warfare emerged, as various scientists and nations proposed the use of asphyxiating or poisonous gases.[9] So alarmed were nations that multiple international treaties, discussed below, were passed – banning chemical weapons. This however did not prevent the extensive use of chemical weapons in World War I. The development of chlorine gas, among others, was used by both sides to try to break the stalemate of trench warfare. Though largely ineffective over the long run, it decidedly changed the nature of the war. In most cases the gases used did not kill, but instead horribly maimed, injured, or disfigured casualties. Estimates for military gas casualties range from 500k to 1.3 million, with a few thousand additional civilian casualties as collateral damage or production accidents.[10][11]

The interwar period saw occasional use of chemical weapons, mainly by multiple European colonial forces to put down rebellions. The Italians also used poison gas during their 1936 invasion of Ethiopia.[12] In Nazi Germany, much research went into developing new chemical weapons, such as potent nerve agents.[13] However, chemical weapons saw little battlefield use in World War II. Both sides were prepared to use such weapons, but the Allied powers never did, and the Axis used them only very sparingly. The reason for the lack of use by the Nazis, despite the considerable efforts that had gone into developing new varieties, might have been a lack of technical ability or fears that the Allies would retaliate with their own chemical weapons. Those fears were not unfounded: the Allies made comprehensive plans for defensive and retaliatory use of chemical weapons, and stockpiled large quantities.[14][15] Japanese forces used them more widely, though only against their Asian enemies, as they also feared that using it on Western powers would result in retaliation. Chemical weapons were frequently used against Kuomintang and Chinese communist troops.[16] However, the Nazis did extensively use poison gas against civilians in the Holocaust. Vast quantities of Zyklon B gas and carbon monoxide were used in the gas chambers of Nazi extermination camps, resulting in the overwhelming majority of some three million deaths. This remains the deadliest use of poison gas in history.[17][18][19][20]

The post-war era has seen limited, though devastating, use of chemical weapons. Some 100,000 Iranian troops were casualties of Iraqi chemical weapons during the Iran–Iraq War.[21][22][23] Iraq used mustard gas and nerve agents against its own civilians in the 1988 Halabja chemical attack.[24] The Cuban intervention in Angola saw limited use of organophosphates.[25] The Syrian government has used sarin, chlorine, and mustard gas in the Syrian civil war – generally against civilians.[26][27] Terrorist groups have also used chemical weapons, notably in the Tokyo subway sarin attack and the Matsumoto incident.[28][29] See also chemical terrorism.

International law

[edit]Before the Second World War

[edit]International law has prohibited the use of chemical weapons since 1899, under the Hague Convention: Article 23 of the Regulations Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land adopted by the First Hague Conference "especially" prohibited employing "poison and poisoned arms".[30][31] A separate declaration stated that in any war between signatory powers, the parties would abstain from using projectiles "the object of which is the diffusion of asphyxiating or deleterious gases".[32]

The Washington Naval Treaty, signed February 6, 1922, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, aimed at banning chemical warfare but did not succeed because France rejected it. The subsequent failure to include chemical warfare has contributed to the resultant increase in stockpiles.[33]

The Geneva Protocol, officially known as the Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare, is an International treaty prohibiting the use of chemical and biological weapons in international armed conflicts. It was signed at Geneva June 17, 1925, and entered into force on February 8, 1928. 133 nations are listed as state parties[34] to the treaty. Ukraine is the newest signatory, acceding August 7, 2003.[35]

This treaty states that chemical and biological weapons are "justly condemned by the general opinion of the civilised world". And while the treaty prohibits the use of chemical and biological weapons, it does not address the production, storage, or transfer of these weapons. Treaties that followed the Geneva Protocol did address those omissions and have been enacted.

Modern agreements

[edit]The 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) is the most recent arms control agreement with the force of International law. Its full name is the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction. That agreement outlaws the production, stockpiling and use of chemical weapons. It is administered by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), which is an independent organization based in The Hague.[36]

The OPCW administers the terms of the CWC to 192 signatories, which represents 98% of the global population. As of June 2016[update], 66,368 of 72,525 metric tonnes, (92% of chemical weapon stockpiles), have been verified as destroyed.[37][38] The OPCW has conducted 6,327 inspections at 235 chemical weapon-related sites and 2,255 industrial sites. These inspections have affected the sovereign territory of 86 States Parties since April 1997. Worldwide, 4,732 industrial facilities are subject to inspection under provisions of the CWC.[38]

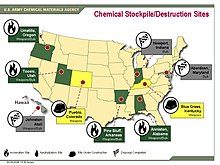

Countries with stockpiles

[edit]In 1985, the United States Congress passed legislation requiring the disposal of the stockpile chemical agents and munitions consisting of over 3 million chemical weapons, adding up to 31,000 tons of chemical weapons needing to be disposed of.[6] This was ordered because a timely and safe disposal of chemical weapons is far safer than chemical weapon storage.[39][7] Between the years of 1982 and 1992, the United States army reported approximately 1,500 leaking chemical weapons munitions, and in 1993 a 100-gallon chemical spill was reported at the Tooele Army Depot in Utah consisting of mustard agents.[6] Chemical decomposition in soil is affected by many factors, such as temperature, acidity, alkalinity, meteorological conditions, and the types of organisms present in the soil, making it difficult to assess and predict safety. Spills of persistent agents, such as sulfur mustards, can remain harmful for decades.[6]

Manner and form

[edit]

There are three basic configurations in which these agents are stored. The first are self-contained munitions like projectiles, cartridges, mines, and rockets; these can contain propellant or explosive components. The next form are aircraft-delivered munitions.[40] Together they constitute the two forms that have been weaponized and are ready for their intended use. The U.S. stockpile consisted of 39% of these weapon ready munitions. The final of the three forms is raw agent housed in bulk containers. The remaining 61%[40] of the US stockpile was stored in this manner.[41] Whereas these chemicals exist in liquid form at normal room temperature,[40][42] the sulfur mustards H and HD freeze in temperatures below 55 °F (12.8 °C). Mixing lewisite with distilled mustard lowers the freezing point to −13 °F (−25.0 °C).[43]

Higher temperatures are a bigger concern because the possibility of an explosion increases as the temperatures rise. A fire at one of these facilities would endanger the surrounding community as well as the personnel at the installations.[44] Perhaps more so for the community having much less access to protective equipment and specialized training.[45] The Oak Ridge National Laboratory conducted a study to assess capabilities and costs for protecting civilian populations during related emergencies,[46] and the effectiveness of expedient, in-place shelters.[47]

Disposal

[edit]The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (December 2012) |

At the end of World War II, the Allies occupied Germany and found large stockpiles of chemical weapons that they did not know how to dispose of or deal with.[48] Ultimately, the Allies disposed large quantities of these chemical weapons into the Baltic Sea, including 32 000 tonnes of chemical munitions and chemical warfare agents dumped into the Bornholm Basin, and another 2000 tonnes of chemical weapons in the Gotland Basin.[48]

The majority of these chemical munitions were dumped into the sea while contained in simple wooden crates, leading to a rapid proliferation of chemicals.[48] Chemical Weapons being disposed in the ocean during the 20th century is not unique to the Baltic Sea, and other heavily contaminated areas where disposal occurred are the European, Japanese, Russian, and United States coasts.[7] These chemical weapons dumped in the ocean pose a continual environmental and human health risk, and chemical agents and breakdown products from said agents have been recently been identified in ocean sediment near historical dumping sites.[7] When chemical weapons are dumped or otherwise improperly disposed of, the chemical agents are quickly distributed over a wide range.[48] The long term impacts of this wide-scale distribution are unknown, but known to be negative.[48] In the Vietnam War of 1955–1975, a chemical weapon called agent orange was widely used by United States forces.[49] The United States utilized agent orange as a type of 'tactical herbicide', aiming to destroy Vietnamese foliage and plant life to ease military access.[49] This usage of agent orange has left lasting impacts that are still observable today in the Vietnamese environment, causing disease, stunted growth, and deformities.[49]

United States

[edit]The stockpiles, which have been maintained for more than 50 years,[33] are now considered obsolete.[50] Public Law 99-145, contains section 1412, which directs the Department of Defense (DOD) to dispose of the stockpiles. This directive fell upon the DOD with joint cooperation from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).[40] The Congressional directive has resulted in the present Chemical Stockpile Disposal Program.

Historically, chemical munitions have been disposed of by land burial, open burning, and ocean dumping (referred to as Operation CHASE).[51] However, in 1969, the National Research Council (NRC) recommended that ocean dumping be discontinued. The Army then began a study of disposal technologies, including the assessment of incineration as well as chemical neutralization methods. In 1982, that study culminated in the selection of incineration technology, which is now incorporated into what is known as the baseline system. Construction of the Johnston Atoll Chemical Agent Disposal System (JACADS) began in 1985.

This was to be a full-scale prototype facility using the baseline system. The prototype was a success but there were still many concerns about CONUS operations. To address growing public concern over incineration, Congress, in 1992, directed the Army to evaluate alternative disposal approaches that might be "significantly safer", more cost effective, and which could be completed within the established time frame. The Army was directed to report to Congress on potential alternative technologies by the end of 1993, and to include in that report: "any recommendations that the National Academy of Sciences makes ..."[41] In June 2007, the disposal program achieved the milestone of reaching 45% destruction of the chemical weapon stockpile.[52] The Chemical Materials Agency (CMA) releases regular updates to the public regarding the status of the disposal program.[53] On July 7, 2023, the program completed destruction of all declared chemical weapons.[54][55]

Lethality

[edit]Chemical weapons are said to "make deliberate use of the toxic properties of chemical substances to inflict death".[56] At the start of World War II it was widely reported in newspapers that "entire regions of Europe" would be turned into "lifeless wastelands".[57] However, chemical weapons were not used to the extent predicted by the press.

An unintended chemical weapon release occurred at the port of Bari. A German attack on the evening of December 2, 1943, damaged U.S. vessels in the harbour and the resultant release from their hulls of mustard gas inflicted a total of 628 casualties.[58][59][60]

The U.S. Government was highly criticized for exposing American service members to chemical agents while testing the effects of exposure. These tests were often performed without the consent or prior knowledge of the soldiers affected.[61] Australian service personnel were also exposed as a result of the "Brook Island trials"[62] carried out by the British Government to determine the likely consequences of chemical warfare in tropical conditions; little was known of such possibilities at that time.

Some chemical agents are designed to produce mind-altering changes, rendering the victim unable to perform their assigned mission. These are classified as incapacitating agents, and lethality is not a factor of their effectiveness.[63]

Unitary versus binary weapons

[edit]Binary munitions contain two, unmixed and isolated chemicals that do not react to produce lethal effects until mixed. This usually happens just prior to battlefield use. In contrast, unitary weapons are lethal chemical munitions that produce a toxic result in their existing state.[64] The majority of the chemical weapon stockpile is unitary and most of it is stored in one-ton bulk containers.[65][66]

See also

[edit]- 1990 Chemical Weapons Accord

- CB military symbol

- General-purpose criterion

- List of chemical warfare agents

- Riot control

References

[edit]- ^ "Types of Chemical Weapons" (PDF). www.fas.org. Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ "Brief Description of Chemical Weapons". Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ^ Vilches, Diego; Alburquerque, Germán; Ramirez-Tagle, Rodrigo (July 2016). "One hundred and one years after a milestone: Modern chemical weapons and World War I". Educación Química. 27 (3): 233–236. doi:10.1016/j.eq.2016.04.004.

- ^ Longerich, Peter (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

- ^ From Cooperation to Complicity: Degussa in the Third Reich, Peter Hayes, 2004, pp 2, 272, ISBN 0-521-78227-9

- ^ a b c d Blackwood, Milton E (June 1998). "Beyond the Chemical Weapons Stockpile: The Challenge of Non-Stockpile Materiel | Arms Control Association". www.armscontrol.org. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Greenberg, M. I.; Sexton, K. J.; Vearrier, D. (February 7, 2016). "Sea-dumped chemical weapons: environmental risk, occupational hazard". Clinical Toxicology. 54 (2): 79–91. doi:10.3109/15563650.2015.1121272. ISSN 1556-3650. PMID 26692048. S2CID 42603071.

- ^ Samir S. Patel, "Early Chemical Warfare – Dura-Europos, Syria," Archaeology, Vol. 63, No. 1, January/February 2010, (accessed October 3, 2014)

- ^ Eric Croddy (2002). Chemical and Biological Warfare: A Comprehensive Survey for the Concerned Citizen. Springer. p. 131. ISBN 9780387950761.

- ^ Haber, L. F. (2002). The Poisonous Cloud: Chemical warfare in the First World War. pp. 239–253. ISBN 9780191512315.

- ^ Gross, Daniel A. (Spring 2015). "Chemical Warfare: From the European Battlefield to the American Laboratory". Distillations. 1 (1): 16–23. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "Chemical Weapons" in Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia, 2d ed. (eds. David H. Shinn & Thomas P. Ofcansky: Scarecrow Press, 2013).

- ^ Corum, James S., The Roots of Blitzkrieg, University Press of Kansas, USA, 1992, pp.106-107.

- ^ Paxman and Harris: Churchill's plans 'to drench Germany with poison gas' and anthrax - Robert Harris and Jeremy Paxman, p132-35.

- ^ Callum Borchers, Sean Spicer takes his questionable claims to a new level in Hitler-Assad comparison, The Washington Post (April 11, 2017).

- ^ Yuki Tanaka, Poison Gas, the Story Japan Would Like to Forget, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, October 1988, p. 16-17

- ^ "Nazi Camps". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ Schwartz, Terese Pencak. "The Holocaust: Non-Jewish Victims". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ Patrick Coffey, American Arsenal: A Century of Weapon Technology and Strategy (Oxford University Press, 2014), p. 152-54.

- ^ James J. Wirtz, "Weapons of Mass Destruction" in Contemporary Security Studies (4th ed.), ed. Alan Collins, Contemporary Security Studies (Oxford University Press, 2016), p. 302.

- ^ Fassihi, Farnaz (October 27, 2002), "In Iran, grim reminders of Saddam's arsenal", New Jersey Star Ledger, archived from the original on December 13, 2007, retrieved April 22, 2020

- ^ Paul Hughes (January 21, 2003), "It's like a knife stabbing into me", The Star (South Africa)

- ^ Sciolino, Elaine (February 13, 2003), "Iraq Chemical Arms Condemned, but West Once Looked the Other Way", The New York Times, archived from the original on May 27, 2013

- ^ On this day: 1988: Thousands die in Halabja gas attack, BBC News (March 16, 1988).

- ^ Tokarev, Andrei; Shubin, Gennady, eds. (2011). Bush War: The Road to Cuito Cuanavale: Soviet Soldiers' Accounts of the Angolan War. Auckland Park: Jacana Media (Pty) Ltd. pp. 128–130. ISBN 978-1-4314-0185-7.

- ^ "CDC | Facts About Sarin". www.bt.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on April 14, 2003. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ Syria Used Chlorine in Bombs Against Civilians, Report Says, The New York Times, Rick Gladstone, August 24, 2016 retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ^ "Japan executes sarin gas attack cult leader Shoko Asahara and six members". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 22, 2019. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ Seto, Yasuo. "The Sarin Gas Attack in Japan and the Related Forensic Investigation." The Sarin Gas Attack in Japan and the Related Forensic Investigation. Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, June 1, 2001. Web. February 24, 2017.

- ^ Article 23. wikisource.org. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ "Laws of War: Laws and Customs of War on Land (Hague II); Article 23". www.yale.edu. July 29, 1899. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ "Laws of War: Declaration on the Use of Projectiles the Object of Which is the Diffusion of Asphyxiating or Deleterious Gases". www.yale.edu. July 29, 1899. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ a b Shrivastav, Sanjeev Kumar (January 1, 2010). "United States of America: Chemical Weapons Profile". www.idsa.in. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ "Geneva Protocol reservations: Project on Chemical and Biological Warfare". www.sipri.org. Archived from the original on September 6, 2013. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ "High Contracting Parties to the Geneva Protocol". www.sipri.org. Archived from the original on September 6, 2013. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ "Status as at: 07-11-2010 01:48:46 EDT, Chapter XXVI, Disarmament". www.un.org. Archived from the original on April 7, 2015. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ "Demilitarisation". www.opcw.org. Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ^ a b "Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (home page)". www.opcw.org. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ Carnes, Sam Abbott; Watson, Annetta Paule (August 4, 1989). "Disposing of the US Chemical Weapons Stockpile: An Approaching Reality". JAMA. 262 (5): 653–659. doi:10.1001/jama.1989.03430050069029. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 2746817.

- ^ a b c d "Public Law 99-145 Attachment E" (PDF). www.fema.gov.

- ^ a b "Chemical Stockpile Disposal Program Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement Volume 3: Appendices A-S – Storming Media". Stormingmedia.us. Archived from the original on September 7, 2013. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

- ^ "Record Version Written Statement by Carmen J. Spencer Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Army" (PDF). www.chsdemocrats.house.govhouse.gov. June 15, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 11, 2013. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- ^ "FM 3–9 (field manual)" (PDF). Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ Rogers, G. O.; Watson, A. P.; Sorensen, J. H.; Sharp, R. D.; Carnes, S. A. (April 1, 1990). "Evauluating Protective Actions for Chemical Agent Emergencies" (PDF). www.emc.ed.ornl.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 11, 2013. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- ^ "Methods for Assessing and Reducing Injury from Chemical Accidents" (PDF). John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Technical Options for Protecting Civilians from Toxic Vapors and Gases" (PDF). Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 13, 2010. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Effectiveness of expedient sheltering in place in a residents" (PDF). Journal of Hazardous Materials, Elsiver.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 11, 2013. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Glasby, G. P. (November 5, 1997). "Disposal of chemical weapons in the Baltic Sea". Science of the Total Environment. 206 (2): 267–273. Bibcode:1997ScTEn.206..267G. doi:10.1016/S0048-9697(97)80015-0. ISSN 0048-9697. PMID 9394485.

- ^ a b c Young, Alvin L. (April 21, 2009). The history, use, disposition, and environmental fate of Agent Orange. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-87486-9. OCLC 1066598939.

- ^ John Pike. "Chemical Weapons". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- ^ John Pike. "Operation CHASE (for "Cut Holes and Sink 'Em")". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

- ^ "45 Percent CWC Milestone". U.S. Army Chemical Materials Agency. Archived from the original on June 8, 2011. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Agent Destruction Status". United States Army Chemical Materials Agency. Archived from the original on June 24, 2010. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Last Chemical Weapon Destroyed at Blue Grass Army Depot - Program Executive Office Assembled Chemical Weapons Alternative". July 8, 2023. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Destruction Progress: PEO ACWA U.S. Chemical Weapons". July 8, 2023. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "TextHandbook-EforS.fm" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 3, 2007. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

- ^ "[2.0] A History of Chemical Warfare (2)". Vectorsite.net. Archived from the original on June 4, 2017. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

- ^ "Mustard Disaster at Bari". www.mcm.fhpr.osd.mil. Archived from the original on November 11, 2013. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- ^ "Naval Armed Guard: at Bari, Italy". History.navy.mil. Archived from the original on April 9, 2010. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

- ^ "Text of the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention". www.brad.ac.uk. Archived from the original on September 7, 2013. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ "Is Military Research Hazardous to Veterans' Health? Lessons Spanning Half a Century. United States Senate December 8, 1994". Gulfweb.org. Archived from the original on August 13, 2006. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

- ^ "Brook Island Trials of Mustard Gas during WW2". Home.st.net.au. Retrieved September 15, 2010.

- ^ "007 Incapacitating Agents". Brooksidepress.org. Archived from the original on June 16, 2010. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

- ^ Alternative technologies for the destruction of chemicam agents and munitions. National Research Council (U.S.). 1993. ISBN 9780309049467.

- ^ "Beyond the Chemical Weapons Stockpile: The Challenge of Non-Stockpile Materiel". Armscontrol.org. Archived from the original on September 8, 2013. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ Institute of Medicine; Committee on the Survey of the Health Effects of Mustard Gas and Lewisite (1993). Veterans at Risk: The Health Effects of Mustard Gas and Lewisite. National Academies Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-309-04832-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Glenn Cross, Dirty War: Rhodesia and Chemical Biological Warfare, 1975–1980, Helion & Company, 2017

External links

[edit]- Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons Home page

- Lecture by Santiago Oñate Laborde entitled The Chemical Weapons Convention: an Overview in the Lecture Series of the United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law

- "The Government of Canada 'Challenge' for chemical substances that are a high priority for action". November 28, 2006.

- "Chemical categories". Archived from the original on November 8, 2005.

- "U.S. Army Chemical Materials Agency (home page)". Archived from the original on October 15, 2004. Retrieved August 10, 2010.