Draft:Alcohol and society

| Draft article not currently submitted for review.

This is a draft Articles for creation (AfC) submission. It is not currently pending review. While there are no deadlines, abandoned drafts may be deleted after six months. To edit the draft click on the "Edit" tab at the top of the window. To be accepted, a draft should:

It is strongly discouraged to write about yourself, your business or employer. If you do so, you must declare it. Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Last edited by Qwerfjkl (bot) (talk | contribs) 22 hours ago. (Update) |

Social issues

[edit]

Alcohol-related crimes

[edit]Alcohol use is stereotypically associated with crime,[3] both violent and non-violent.[4] Some crimes are uniquely tied to alcohol, such as public intoxication or underage drinking, while others are simply more likely to occur together with alcohol consumption. Crime perpetrators are much more likely to be intoxicated than crime victims. Many alcohol laws have been passed to criminalize various alcohol-related activities.[3][5] Underage drinking and drunk driving are the most prevalent alcohol-specific offenses in the United States[3] and a major problem in many countries worldwide.[6][7][8] About one-third of arrests in the United States involve alcohol misuse,[4] and arrests for alcohol-related crimes constitute a high proportion of all arrests made by police in the U.S. and elsewhere.[9] In general, programs aimed at reducing society's consumption of alcohol, including education in schools, are seen as an effective long-term solution. Strategies aiming to reduce alcohol consumption among adult offenders have various estimates of effectiveness.[10] Policing alcohol-related street disorder and enforcing compliance checks of alcohol-dispensing businesses has proven successful in reducing public perception of and fear of criminal activities.[3]

In the early 2000s, the monetary cost of alcohol-related crime in the United States alone has been estimated at over $205 billion, twice the economic cost of all other drug-related crimes.[11] In a similar period in the United Kingdom, the cost of crime and its antisocial effects was estimated at £7.3 billion.[10] Another estimate for the UK for yearly cost of alcohol-related crime suggested double that estimate, at between £8 and 13 billion.[12] Risky patterns of drinking are particularly problematic in and around Russia, Mexico and some parts of Africa.[13] Alcohol is more commonly associated with both violent and non-violent crime than are drugs like marijuana.[4]

Passive drinking, like passive smoking, refers to the damage done to others as a result of drinking alcoholic beverages. These include the unborn fetus and children of parents who drink excessively, drunk drivers, accidents, domestic violence and alcohol-related sexual assaults[14]

Public-order crimes

[edit]Public-order crimes caused by drinking include drunk driving, domestic violence, and alcohol-related sexual assaults.

Automobile accidents

[edit]

A 2002 study found 41% of people fatally injured in traffic accidents were in alcohol-related crashes.[15] Misuse of alcohol is associated with more than 40% of deaths that occur in automobile accidents every year.[4] The risk of a fatal car accident increases exponentially with the level of alcohol in the driver's blood.[16]

Most countries have passed laws prohibiting driving a motor vehicle while impaired by alcohol. In the U.S., these crimes are generally referred to as driving under the influence (DUI), although there are many naming variations among jurisdictions, such as driving while intoxicated (DWI).[17] With alcohol consumption, a drunk driver's level of intoxication is typically determined by a measurement of blood alcohol content or BAC; but this can also be expressed as a breath test measurement, often referred to as a BrAC. A BAC or BrAC measurement in excess of the specific threshold level, such as 0.08% in the U.S.,[18] defines the criminal offense with no need to prove impairment.[19] In some jurisdictions, there is an aggravated category of the offense at a higher BAC level, such as 0.12%, 0.15% or 0.25%. In many jurisdictions, police officers can conduct field tests of suspects to look for signs of intoxication.

Negligence

[edit]

Negligence in alcohol consumption can have a ripple effect on environmentally responsible behavior. Examples:

- Consuming alcoholic beverages, which increases urine production and reduces social inhibitions, can lead to public urination. Public urination is illegal in most areas.

- Improper disposal of alcohol bottles is a common problem. Many are not recycled or left behind in public spaces. Discarded alcoholic beverage containers, especially broken glass shards that are difficult to remove, does not only create an eyesore but may also cause flat tires for cyclists, injure wildlife or kids.

- Alcohol consumption can contribute to nighttime noise pollution, especially through loud music played by intoxicated individuals. This disrupts sleep and relaxation for nearby residents, impacting health and productivity. Municipal noise ordinances often establish quiet hours and penalties for violations.

- People under the influence may forget to extinguish outdoor fireplaces, which may create a fire hazard since unchecked fires can escalate into wildfires.

- Drunk cyclists can only be charged if they ride dangerously, cause a crash, or behave disruptively.[20] However, cycling under the influence increases the risk of severe injury, hospital resource use, and even death, according to a study highlighting the importance of safe cycling practices.[21]

Public drunkenness

[edit]

Public drunkenness or intoxication is a common problem in many jurisdictions. Public intoxication laws vary widely by jurisdiction, but include public nuisance laws, open-container laws, and prohibitions on drinking alcohol in public or certain areas. The offenders are often lower class individuals and this crime has a very high recidivism rate, with numerous instances of repeated instances of the arrest, jail, release without treatment cycle. The high number of arrests for public drunkenness often reflects rearrests of the same offenders.[9]

Sexual assaults

[edit]Rape is any sexual activity that occurs without the freely given consent of one of the parties involved. This includes alcohol-facilitated sexual assault which is considered rape in most if not all jurisdictions,[22] or non-consensual condom removal which is criminalized in some countries (see the map below).

A 2008 study found that rapists typically consumed relatively high amounts of alcohol and infrequently used condoms during assaults, which was linked to a significant increase in STI transmission.[23] This also increase the risk of pregnancy from rape for female victims. Some people turn to drugs or alcohol to cope with emotional trauma after a rape; use of these during pregnancy can harm the fetus.[24]

Alcohol-facilitated sexual assault

[edit]

One of the most common date rape drugs is alcohol,[26][27][28] administered either surreptitiously[29] or consumed voluntarily,[26] rendering the victim unable to make informed decisions or give consent. The perpetrator then facilitates sexual assault or rape, a crime known as alcohol- or drug-facilitated sexual assault (DFSA).[30][22][31] However, sex with an unconscious victim is considered rape in most if not all jurisdictions, and some assailants have committed "rapes of convenience" whereby they have assaulted a victim after he or she had become unconscious from drinking too much.[32] The risk of individuals either experiencing or perpetrating sexual violence and risky sexual behavior increases with alcohol abuse,[33] and by the consumption of caffeinated alcoholic drinks.[34][35]

Non-consensual condom removal

[edit]

Non-consensual condom removal, or "stealthing",[36] is the practice of a person removing a condom during sexual intercourse without consent, when their sex partner has only consented to condom-protected sex.[37][38] Purposefully damaging a condom before or during intercourse may also be referred to as stealthing,[39] regardless of who damaged the condom.

Consuming alcohol can be risky in sexual situations. It can impair judgment and make it difficult for both people to give or receive informed sexual consent. However, a history of sexual aggression and alcohol intoxication are factors associated with an increased risk of men employing non-consensual condom removal and engaging in sexually aggressive behavior with female partners.[40][41]

Wartime sexual violence

[edit]The use of alcohol is a documented factor in wartime sexual violence.

For example, rape during the liberation of Serbia was committed by Soviet Red Army soldiers against women during their advance to Berlin in late 1944 and early 1945 during World War II. Serbian journalist Vuk Perišić said about the rapes: "The rapes were extremely brutal, under the influence of alcohol and usually by a group of soldiers. The Soviet soldiers did not pay attention to the fact that Serbia was their ally, and there is no doubt that the Soviet high command tacitly approved the rape."[42]

While there was not a codified international law specifically prohibiting rape during World War II, customary international law principles already existed that condemned violence against civilians. These principles formed the basis for the development of more explicit laws after the war,[43] including the Nuremberg Principles established in 1950.

Violent crime

[edit]

The World Health Organization has noted that out of social problems created by the harmful use of alcohol, "crime and violence related to alcohol consumption" are likely the most significant issue.[13] In the United States, 15% of robberies, 63% of intimate partner violence incidents, 37% of sexual assaults, 45–46% of physical assaults and 40–45% of homicides (murders) involved use of alcohol.[45][11] A 1983 study for the United States found that 54% of violent crime perpetrators, arrested in that country, had been consuming alcohol before their offenses.[9] In 2002, it was estimated that 1 million violent crimes in the U.S. were related to alcohol use.[4] More than 43% of violent encounters with police involve alcohol.[4] Alcohol is implicated in more than two-thirds of cases of intimate partner violence.[4] Studies also suggest there may be links between alcohol abuse and child abuse.[3] In the United Kingdom, in 2015/2016, 39% of those involved in violent crimes were under alcohol influence.[46] A significant portion, 40%, of homicide victims tested positive for alcohol in the US.[47] International studies are similar, with an estimate that 63% of violent crimes worldwide involves the use of alcohol.[11]

The relation between alcohol and violence is not yet fully understood, as its impact on different individuals varies.[citation needed] Studies and theories of alcohol abuse suggest, among others, that use of alcohol likely reduces the offender's perception and awareness of consequences of their actions.[28][3][9][48] Heavy drinking is associated with vulnerability to injury, marital discord, and domestic violence.[4] Moderate drinkers are more frequently engaged in intimate violence than are light drinkers and abstainers, however generally it is heavy and/or binge drinkers who are involved in the most chronic and serious forms of aggression. Research found that factors that increase the likelihood of alcohol-related violence include difficult temperament, hyperactivity, hostile beliefs, history of family violence, poor school performance, delinquent peers, criminogenic beliefs about alcohol's effects, impulsivity, and antisocial personality disorder. The odds, frequency, and severity of physical attacks are all positively correlated with alcohol use. In turn, violence decreases after behavioral marital alcoholism treatment.[3]

Methanol laced alcohol

[edit]

Outbreaks of methanol poisoning have occurred when methanol is used to lace moonshine (bootleg liquor).[49] This is commonly done to bulk up the original product to gain profit. Because of its similarities in both appearance and odor to ethanol (the alcohol in beverages), it is difficult to differentiate between the two.

Methanol is a toxic alcohol. If as little as 10 mL of pure methanol is ingested, for example, it can break down into formic acid, which can cause permanent blindness by destruction of the optic nerve, and 30 mL is potentially fatal,[50] although the median lethal dose is typically 100 mL (3.4 fl oz) (i.e. 1–2 mL/kg body weight of pure methanol[51]). Reference dose for methanol is 2.0 mg/kg/day.[52] Toxic effects take hours to start, and effective antidotes can often prevent permanent damage.[50]

India has a thriving moonshine industry, and methanol-tainted batches have killed over 2,000 people in the last 3 decades.

Alternative routes of administration

[edit]Alternative methods of alcohol administration like alcohol enema, alcohol inhalation, vodka eyeballing, or using alcohol powder (which can be added to water to make an alcoholic beverage, or inhaled with a nebulizer), all carry significant health risks.

Binge drinking

[edit]

Binge drinking is a style of drinking that is popular in several countries worldwide, and overlaps somewhat with social drinking since it is often done in groups. The degree of intoxication however, varies between and within various cultures that engage in this practice. A binge on alcohol can occur over hours, last up to several days, or in the event of extended abuse, even weeks. Due to the long term effects of alcohol abuse, binge drinking is considered to be a major public health issue.[53]

Binge drinking is more common in males, during adolescence and young adulthood. Heavy regular binge drinking is associated with adverse effects on neurologic, cardiac, gastrointestinal, hematologic, immune, and musculoskeletal organ systems as well as increasing the risk of alcohol induced psychiatric disorders.[54][55] A US-based review of the literature found that up to one-third of adolescents binge-drink, with 6% reaching the threshold of having an alcohol-related substance use disorder.[56] Approximately one in 25 women binge-drinks during pregnancy, which can lead to fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.[57] Binge drinking during adolescence is associated with traffic accidents and other types of accidents, violent behavior as well as suicide. The more often a child or adolescent binge drinks and the younger they are the more likely that they will develop an alcohol use disorder including alcoholism. A large number of adolescents who binge-drink also consume other psychotropic substances.[58]

Emotional issues

[edit]In emotional self-regulation, some people turn to drugs such as alcohol. Drug use, an example of response modulation, can be used to alter emotion-associated physiological responses. For example, alcohol can produce sedative and anxiolytic effects.[59] A 2013 study found that immature defense mechanisms are linked to placing a higher value on junk food, alcohol, and television.[60]

There is a two-way street between loneliness and drinking. People who drink more than once a week tend to feel lonelier, according to a study on Japanese workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.[61] On the other hand, feelings of loneliness can also lead people to drink more, as shown in a separate study.[62] Loneliness is a major risk factor for depression and alcoholism.[63]

Hurtful communication

[edit]Alcohol may cause hurtful communication.

Drunk dialing

[edit]Drunk dialing refers to an intoxicated person making phone calls that they would not likely make if sober, often a lonely individual calling former or current love interests.

A 2021 study, that examined the relationship between drunk texting and emotional dysregulation, found a positive correlation. The findings suggest that interventions targeting emotional regulation skills may be beneficial.[64]

In vino veritas

[edit]In vino veritas is a Latin phrase that means 'in wine, there is truth', suggesting a person under the influence of alcohol is more likely to speak their hidden thoughts and desires.

Risky sexual behavior

[edit]Some studies have made a connection between hookup culture and substance use.[65] Most students said that their hookups occurred after drinking alcohol.[65][66][67] Frietas stated that in her study, the relationships between drinking and the party scene and between alcohol and hookup culture were "impossible to miss".[68]: 41

Studies suggest that the degree of alcoholic intoxication in young people directly correlates with the level of risky behavior,[69] such as engaging in multiple sex partners.[70]

In 2018, the first study of its kind, found that alcohol and caffeinated energy drinks is linked with casual, risky sex among college-age adults.[35]

Sexually transmitted infections and unintended pregnancy

[edit]

Alcohol intoxication is associated with an increased risk that people will become involved in risky sexual behaviors, such as unprotected sex.[71] Both men,[72] and women,[73] reported higher intentions to avoid using a condom when they were intoxicated by alcohol.

Coitus interruptus, also known as withdrawal, pulling out or the pull-out method, is a method of birth control during penetrative sexual intercourse, whereby the penis is withdrawn from a vagina or anus prior to ejaculation so that the ejaculate (semen) may be directed away in an effort to avoid insemination.[74][75] Coitus interruptus carries a risk of STIs and unintended pregnancy. This risk is especially high during alcohol intoxication because lowered sexual inhibition can make it difficult to withdraw in time.

Women with unintended pregnancies are more likely to smoke tobacco,[76] drink alcohol during pregnancy,[77][78] and binge drink during pregnancy,[76] which results in poorer health outcomes.[77] (See also: fetal alcohol spectrum disorder)

Female sex workers in low- and middle-income countries have high rates of harmful alcohol use, which is associated with increased risk of risky sexual behavior.[79] A bargirl is involved in a transaction known as a bar fine, which is a fee paid by a customer to the operators of a bar or nightclub in East and Southeast Asia, allowing her to leave work early, typically to accompany a customer outside for sexual services.[80] Screening carried out in the 1990s in Malawi, an African country, indicated that about 80 per cent of bargirls carried the HIV virus. Research carried out at the time indicated that economic necessity was a major consideration in engaging and persisting in sex work.[81]

Societal damage

[edit]

Alcohol causes a plethora of detrimental effects in society.[4] A 2023 systematic review estimated the societal costs of alcohol use to be around 2.6% of the GDP.[82] Many emergency room visits involve alcohol use.[4] Alcohol availability and consumption rates and alcohol rates are positively associated with nuisance, loitering, panhandling, and disorderly conduct in public space.[3]

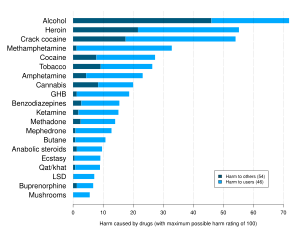

A 2011 study challenged the perception of heroin as the more dangerous substance. The research suggests, when considering the wider social, physical, and financial costs, alcohol may be more harmful.[83]

Individuals who engage with or share alcohol-related content on social networking services tend to exhibit higher levels of alcohol use and related issues.[84] Overwork is linked to an increased risk of unhealthy alcohol consumption.[85] Also, unemployment can heighten the risk of alcohol consumption and smoking.[86] As many as 15% of employees show problematic alcohol-related behaviors in the workplace, such as drinking before going to work or even drinking on the job.[4]

College

[edit]Many students attending colleges, universities, and other higher education institutions consume alcoholic beverages. The laws and social culture around this practice vary by country and institution type, and within an institution, some students may drink heavily whereas others may not drink at all. In the United States, drinking tends to be particularly associated with fraternities.

Alcohol abuse among college students refers to unhealthy alcohol drinking behaviors by college and university students. While the legal drinking age varies by country, the high number of underage students that consume alcohol has presented many problems and consequences for universities. The causes of alcohol abuse tend to be peer pressure, fraternity or sorority involvement, and stress. College students who abuse alcohol can suffer from health concerns, poor academic performance or legal consequences. Prevention and treatment include campus counseling, stronger enforcement of underage drinking or changing the campus culture.

Recent research indicates that the abundance of alcohol retailers and the availability of inexpensive alcoholic beverages are linked to heavy alcohol consumption among college students.[87]

Poverty

[edit]Alcohol consumption can contribute to secondary poverty (where people fall back into poverty after escaping it). The Bureau of Labor Statistics found that "the average American consumer dedicates 1 percent of all their spending to alcohol".[88]

Unsustainable tourism

[edit]Some popular tourist destinations, are cracking down on the impacts of tourism from excessive drinking. In an effort to promote a more sustainable tourism industry, these locations are implementing new regulations to curb binge drinking. This includes Llucmajor, Palma, Calvia (Magaluf) in Majorca and Sant Antoni in Ibiza, where late-night sales of alcohol will be banned. This comes after years of issues with rowdy tourists and the negative impacts it has on local residents.[89]

Suicide

[edit]Most people are under the influence of sedative-hypnotic drugs (such as alcohol or benzodiazepines) when they die by suicide,[90] with alcoholism present in between 15% and 61% of cases.[91] Countries that have higher rates of alcohol use and a greater density of bars generally also have higher rates of suicide.[92] About 2.2–3.4% of those who have been treated for alcoholism at some point in their life die by suicide.[92] Alcoholics who attempt suicide are usually male, older, and have tried to take their own lives in the past.[91] In adolescents who misuse alcohol, neurological and psychological dysfunctions may contribute to the increased risk of suicide.[93]

Society and culture

[edit]Evolving alcohol norms

[edit]Alcohol education

[edit]Alcohol education is the planned provision of information and skills relevant to living in a world where alcohol is commonly misused.[94] The World Health Organisations (WHO) Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health, highlights the fact that alcohol will be a larger problem in later years, with estimates suggesting it will be the leading cause of disability and death.[95] Informing people on alcohol and harmful drinking should become a priority.

Denormalization

[edit]In October 2024, the WHO Regional Office for Europe has launched the "Redefine alcohol" campaign to address alcohol-related health risks, as alcohol causes nearly 1 in 11 deaths in the region. The campaign aims to raise awareness about alcohol's link to over 200 diseases, including several cancers, and to encourage healthier choices by sharing research and personal stories. It also calls for stricter regulation of alcohol to reduce its societal harm. This initiative is part of the WHO/EU Evidence into Action Alcohol Project, which seeks to reduce alcohol-related harm across Europe.[96]

Intermittent sobriety

[edit]Intermittent sobriety refers to planned periods of abstinence from alcohol, often as part of awareness campaigns or personal health initiatives.[97][98]

Notable examples include:

- Dry January: An annual campaign encouraging people to abstain from alcohol for the month of January.

- Dry July: A similar initiative held in July, often with a fundraising component for cancer-related charities.

- Ocsober: An October-based challenge to abstain from alcohol.

Sober curious

[edit]

Sober curious is a cultural movement and lifestyle of consuming no or limited alcohol that started in the late 2010s.[citation needed] It differs from traditional abstinence in that it is not founded on asceticism, religious condemnation of alcohol or previous alcohol abuse, but motivated by a curiosity of a sober lifestyle. Markets have reacted by offering a wider selection of non-alcoholic beverages.[99]

Sober curiosity is often defined as having the option to question or change one's drinking habits, for mental or physical health reasons.[100] It may be practised in many ways, ranging from complete abstinence to more thought about when and how much is consumed.[101]

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, more people in Europe have reduced their alcohol consumption.[102]

Usage

[edit]Consumption recommendations

[edit]

The recommended maximum intake (or safe limits) of alcohol varies from no intake, to daily, weekly, or daily/weekly guidelines provided by health agencies of governments. The World Health Organization published a statement in The Lancet Public Health in April 2023 that "there is no safe amount that does not affect health".[103]

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, based on NHANES 2013–2014 surveys, women in the US ages 20 and up consume on average 6.8 grams/day and men consume on average 15.5 grams/day.[104] A March 2023 review found light-moderate daily drinking not significantly associated with increased mortality rate, but higher intake raises risk, with women affected at lower levels than men.[105] However, according to a 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis, even at 20 g/day (1 large beer), the risk of developing an alcohol use disorder (AUD) is nearly 3 times higher than non-drinkers, and the risk of dying from an AUD is about 2 times higher than non-drinkers.[106]

Drinking culture

[edit]

Ethanol is typically consumed as a recreational substance by mouth in the form of alcoholic beverages such as beer, wine, and spirits. It is commonly used in social settings due to its capacity to enhance sociability.

Drinking alcohol is generally socially acceptable and is legal in most countries, unlike with many other recreational substances. Many students attending colleges, universities, and other higher education institutions consume alcoholic beverages. However, there are often restrictions on alcohol sale and use, for instance a minimum age for drinking and laws against public drinking and drinking and driving.[107] A 2024 meta-analysis found that alcohol consumption increased on average each year, with the most significant rise occurring between the ages of 12 and 13. Drinking peaked around 22 years old, then began to decline at 24.[108]

Alcohol holds considerable societal and cultural significance, playing a role in social interactions across much of the world. Drinking establishments, such as bars and nightclubs, revolve primarily around the sale and consumption of alcoholic beverages, and parties, festivals, and social gatherings commonly involve alcohol consumption. Alcohol is related to various societal problems, including drunk driving, accidental injuries, sexual assaults, domestic abuse, and violent crime.[4] Alcohol remains illegal for sale and consumption in a number of countries, mainly in the Middle East.

Research on the societal benefits of alcohol is rare, but a 2017 study suggested there it was beneficial.[109] Alcohol is often used as a social lubricant; it increases occurrences of Duchenne smiling, talking, and social bonding, even when participants are unaware of their alcohol consumption or lack thereof.[110] In a study of the UK, regular drinking was correlated with happiness, feeling that life was worthwhile, and life satisfaction. According to a causal path analysis the cause was vice versa; alcohol consumption was not the cause, but rather that the life satisfaction resulted in greater happiness and an inclination to visit pubs and develop a regular drinking venue. City centre bars were distinguished by their focus on maximizing alcohol sales. Community pubs had less variation in visible group sizes and longer, more focused conversations than those in city centre bars. Drinking regularly at a community pub led to higher trust in others and better networking with the local community, compared to non-drinkers and city centre bar drinkers.[109]

Psychosocial factors

[edit]Research has shown that various psychosocial factors can influence alcohol consumption patterns throughout an individual's life.

A 2024 study from UT Southwestern Medical Center indicates that higher IQ during high school is linked to a greater likelihood of moderate or heavy drinking in midlife, with each one-point increase in IQ correlating to a 1.6% higher probability of such drinking. The study also found that this relationship is influenced by psychosocial factors, particularly income and career stress, highlighting the need for further research in diverse populations.[111][112]

Religion

[edit]

The relationship between religion and alcohol exhibits variations across cultures, geographical areas, and religious denominations. Some religions emphasize moderation and responsible use as a means of honoring the divine gift of life, while others impose outright bans on alcohol as a means of honoring the divine gift of life. Moreover, within the same religious tradition, there are many adherents that may interpret and practice their faith's teachings on alcohol in diverse ways. Hence, a wide range of factors, such as religious affiliation, levels of religiosity, cultural traditions, family influences, and peer networks, collectively influence the dynamics of this relationship.

The levels of alcohol use in spiritual context can be broken down into:

- Prohibition: Some religions, including Islam[113] prohibit alcohol consumption.

- Symbolic use: In some Christian denominations, the sacramental wine is alcoholic, however, only a sip is taken, and it does not raise the blood alcohol content, and other denominations are using nonalcoholic wine. See also Libation.

- Discourage consumption: Hinduism does not have a central authority which is followed by all Hindus, though religious texts generally discourage the use or consumption of alcohol.

- Inebriating spiritual use: See the spiritual section.

- Recreational use: Recreational drug use of alcohol in moderation to celebrate joy, is allowed in some religions.

- Christian views on alcohol are varied. For example, in the mid-19th century, some Protestant Christians moved from a position of allowing moderate use of alcohol (sometimes called moderationism) to either deciding that not imbibing was wisest in the present circumstances (abstentionism) or prohibiting all ordinary consumption of alcohol because it was believed to be a sin (prohibitionism).[114]

- Alcohol in the Bible explores the dual role of alcohol, highlighting its positive uses and warnings against excess. In biblical narratives, the fermentation of fruit into wine holds significance, with grapes and wine often linked to both celebration and cautionary tales of sin and temptation, reminiscent of the concept of the forbidden fruit.[citation needed]

- During the Jewish holiday of Purim, Jews are obligated to drink (especially Kosher wine) until their judgmental abilities become impaired according to the Book of Esther.[115][116][117] However, Purim has more of a national than a religious character.

Misconceptions

[edit]While the terms "drug" and "medicine" are sometimes used interchangeably, "drug" can have a negative connotation, often associated with illegal substances like cocaine or heroin.[118] Criticism of the alcohol industry may note that the industry argues that "alcohol is not a drug".[119][120] However, the term "Alcohol and Other Drugs" emphasizes this inclusion by grouping alcohol with other substances that alter mood and behavior.

The term narcotic usually refers to opiates or opioids, which are called narcotic analgesics. In common parlance and legal usage, it is often used imprecisely to mean illicit drugs, irrespective of their pharmacology.[121] However, in countries with alcohol prohibition, it is classified and treated as a narcotic. Also, research acknowledges that alcohol can have similar effects to narcotics in head and/or trunk trauma situations.[122] In addition to these findings, recent research indicates that among chronic pain patients on long-term opioid therapy, alcohol consumption is connected to heightened opioid cravings.[123]

The normalization of alcohol consumption,[124] along with past misconceptions about its health benefits, also promoted by the industry,[125] further reinforces the mistaken idea that it is not a "drug". Even within the realm of scientific inquiry, the common phrase "drugs and alcohol" persists, implying that alcohol is somehow separate from other drugs.

Paradoxically, despite being legal, alcohol, scientifically classified as a drug, has demonstrably been linked to greater social harm than most illegal drugs.[1][2] This contradicts the perception some hold of alcohol being a harmless substance.

Law

[edit]Legal status

[edit]

Alcohol consumption is fully legal and available in most countries of the world.[126] Home made alcoholic beverages with low alcohol content like wine, and beer is also legal in most countries, but distilling moonshine outside of a registered distillery remains illegal in most of them.

Some majority-Muslim countries, such as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Pakistan, Iran and Libya prohibit the production, sale, and consumption of alcoholic beverages because they are forbidden by Islam.[127][128][129] Laws banning alcohol consumption are found in some Indian states as well as some Native American reservations in the U.S.[126]

In addition, there are regulations on alcohol sales and use in many countries throughout the world.[126] For instance, the majority of countries have a minimum legal drinking age to purchase or consume alcoholic beverages, although there are often exceptions such as underage consumption of small amounts of alcohol with parental supervision. Also, some countries have bans on public intoxication.[126] Drinking while driving or intoxicated driving is frequently outlawed and it may be illegal to have an open container of alcohol or liquor bottle in an automobile, bus or aircraft.[126]

In Iran, consumption of alcohol (one glass) is punished by 80 lashes, but repeated offences may lead to death penalty, although rarely exercised. In 2012, two men were sentenced to death after a third offense in Khorasan.[130][131]

Alcohol packaging warning messages

[edit]

Alcohol packaging warning messages (alcohol warning labels, AWLs[132]) are warning messages that appear on the packaging of alcoholic drinks concerning their health effects.

A World Health Organization report, published in 2017, stated:[133]

Alcohol product labelling could be considered as a component of a comprehensive public health strategy to reduce alcohol-related harm. Adding health labels to alcohol containers is an important first step in raising awareness and has a longer-term utility in helping to establish a social understanding of the harmful use of alcohol.

Minimum pricing policies

[edit]In 2018, Scotland became the first country to implement a minimum unit pricing policy for alcohol, setting the price at 50 pence per unit. This measure aimed to reduce alcohol-related harm by making cheap, high-strength alcohol less accessible. As of September 2024, the minimum price has increased to 65 pence per unit, reflecting efforts to address inflation and continue reducing alcohol-related deaths and hospital admissions.[134]

Criticism of the alcohol industry

[edit]

A 2019 survey conducted by the American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR) showed that only 45% of Americans were aware of the associated risk of cancer due to alcohol consumption, up from 39% in 2017.[135] The AICR believes that alcohol advertising about the healthy cardiovascular benefits of modest alcohol overshadow messages about the increased cancer risks.[135]

Drinking alcoholic beverages increase the risk for breast cancer. Several studies indicate that the use of marketing by the alcohol industry to associate their products with breast cancer awareness campaigns, known as pinkwashing, is misleading and potentially harmful.[136][137][138][139]

The alcohol industries have marketed products directly to the LGBT+ community. In 2010, of the sampled parades that listed sponsors, 61% of the prides were sponsored by the alcohol industry.[140] A study found that alcohol consumption within LGBTQ+ communities presents a challenge for health promotion efforts. The positive association with alcohol within these communities makes it harder to reduce alcohol-related health issues.[141]

Standard drink

[edit]A standard drink is a measure of alcohol consumption representing a fixed amount of pure ethanol, used in relation to recommendations about alcohol consumption and its relative risks to health. The size of a standard drink varies from 8g to 20g across countries, but 10g alcohol (12.7 millilitres) is used in the World Health Organization (WHO) Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)'s questionnaire form example,[142] and has been adopted by more countries than any other amount.[143]

- ^ a b Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD (November 2010). "Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis". Lancet. 376 (9752): 1558–1565. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.1283. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. PMID 21036393. S2CID 5667719.

- ^ a b Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, Blakemore C (March 2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831. S2CID 5903121.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sunga HE (2016). "Alcohol and Crime". The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. American Cancer Society. pp. 1–2. doi:10.1002/9781405165518.wbeosa039.pub2. ISBN 978-1-4051-6551-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Butcher JN, Hooley JM, Mineka SM (25 June 2013). Abnormal Psychology. Pearson Education. p. 370. ISBN 978-0-205-97175-6.

- ^ Trevor B, Katy H (1 April 2005). Understanding Drugs, Alcohol And Crime. McGraw-Hill Education (UK). p. 6. ISBN 978-0-335-21257-6.

- ^ "Drunk Driving Statistics in the US and Across the World". Law Office of Douglas Herring. 13 November 2017. Archived from the original on 22 September 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ "Drunk Driving Increasing Concern Worldwide". Voice of America. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ Sweedler BM, Stewart K (2009). "Worldwide trends in alcohol and drug impaired driving". In Verster JC, Pandi-Perumal SR, Ramaekers JG, de Gier JJ (eds.). Drugs, Driving and Traffic Safety. Birkhäuser Basel. pp. 23–41. doi:10.1007/978-3-7643-9923-8_2. ISBN 978-3-7643-9923-8.

- ^ a b c d Clinard M, Meier R (14 February 2007). Sociology of Deviant Behavior. Cengage Learning. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-495-09335-0.

- ^ a b McMurran M (3 October 2012). Alcohol-Related Violence: Prevention and Treatment. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 337–338. ISBN 978-1-118-41106-3.

- ^ a b c McMurran M (3 October 2012). Alcohol-Related Violence: Prevention and Treatment. John Wiley & Sons. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-118-41106-3.

- ^ "WHO | Governments confront drunken violence". WHO. Archived from the original on 4 May 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ a b "Global status report on alcohol and health" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2011.

- ^ Smith R (16 March 2010). "'Passive drinking' is blighting the nation, Sir Liam Donaldson warns". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ^ Hingson R, Winter M (2003). "Epidemiology and consequences of drinking and driving". Alcohol Research & Health. 27 (1): 63–78. PMC 6676697. PMID 15301401.

- ^ Naranjo CA, Bremner KE (January 1993). "Behavioural correlates of alcohol intoxication". Addiction. 88 (1): 25–35. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02761.x. PMID 8448514.

- ^ Driving Under the Influence: A Report to Congress on Alcohol Limits. U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. 1992. pp. 1–.

- ^ "Legislative History of .08 per se Laws – NHTSA". NHTSA. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. July 2001. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ Nelson B. "Nevada's Driving Under the Influence (DUI) laws". NVPAC. Advisory Council for Prosecuting Attorneys. Archived from the original on 22 April 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ Bothorn JB, Schwender H, Graw M, Kienbaum P, Hartung B (July 2022). "Cycling under the influence of alcohol-criminal offenses in a German metropolis". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 136 (4): 1121–1132. doi:10.1007/s00414-022-02828-8. PMC 9170663. PMID 35474490.

- ^ Sethi M, Heyer JH, Wall S, DiMaggio C, Shinseki M, Slaughter D, Frangos SG (June 2016). "Alcohol use by urban bicyclists is associated with more severe injury, greater hospital resource use, and higher mortality". Alcohol. 53: 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2016.03.005. PMC 5248656. PMID 27286931.

- ^ a b Hall JA, Moore CB (July 2008). "Drug facilitated sexual assault—a review". Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine. 15 (5): 291–7. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2007.12.005. PMID 18511003.

- ^ Davis KC, Schraufnagel TJ, George WH, Norris J (September 2008). "The use of alcohol and condoms during sexual assault". American Journal of Men's Health. 2 (3): 281–290. doi:10.1177/1557988308320008. PMC 4617377. PMID 19477791.

- ^ Price S (2007). Mental Health in Pregnancy and Childbirth. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 151–152. ISBN 978-0-443-10317-9. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ ElSohly MA, Salamone SJ (1999). "Prevalence of drugs used in cases of alleged sexual assault". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 23 (3): 141–146. doi:10.1093/jat/23.3.141. PMID 10369321.

- ^ a b "Alcohol Is Most Common 'Date Rape' Drug". Medicalnewstoday.com. Archived from the original on 17 October 2007. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ^ Schwartz RH, Milteer R, LeBeau MA (June 2000). "Drug-facilitated sexual assault ('date rape')". Southern Medical Journal. 93 (6): 558–61. doi:10.1097/00007611-200093060-00002. PMID 10881768.

- ^ a b Holstege CP, Saathoff GB, Neer TM, Furbee RB, eds. (25 October 2010). Criminal poisoning: clinical and forensic perspectives. Sudbury, Mass.: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. pp. 232. ISBN 978-0-7637-4463-2.

- ^ Lyman MD (2006). Practical drug enforcement (3rd ed.). Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC. p. 70. ISBN 0-8493-9808-8.

- ^ Thompson KM (January 2021). "Beyond roofies: Drug- and alcohol-facilitated sexual assault". JAAPA. 34 (1): 45–49. doi:10.1097/01.JAA.0000723940.92815.0b. PMID 33332834.

- ^ Beynon CM, McVeigh C, McVeigh J, Leavey C, Bellis MA (July 2008). "The involvement of drugs and alcohol in drug-facilitated sexual assault: a systematic review of the evidence". Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 9 (3): 178–88. doi:10.1177/1524838008320221. PMID 18541699. S2CID 27520472.

- ^ "Date Rape". Survive.org.uk. 20 March 2000. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ^ Chersich MF, Rees HV (January 2010). "Causal links between binge drinking patterns, unsafe sex and HIV in South Africa: its time to intervene". International Journal of STD & AIDS. 21 (1): 2–7. doi:10.1258/ijsa.2000.009432. PMID 20029060. S2CID 3100905.

- ^ "Consumption of alcohol/energy drink mixes linked with casual, risky sex". ScienceDaily.

- ^ a b Ball NJ, Miller KE, Quigley BM, Eliseo-Arras RK (April 2021). "Alcohol Mixed With Energy Drinks and Sexually Related Causes of Conflict in the Barroom". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 36 (7–8): 3353–3373. doi:10.1177/0886260518774298. PMID 29779427. S2CID 29150434.

- ^ Hatch J (21 April 2017). "Inside The Online Community Of Men Who Preach Removing Condoms Without Consent". Huffington Post. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ^ Chesser B, Zahra A (22 May 2019). "Stealthing: a criminal offence?". Current Issues in Criminal Justice. 31 (2). Sydney Law School: 217–235. doi:10.1080/10345329.2019.1604474. S2CID 182850828. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ Brodsky A (2017). "'Rape-Adjacent': Imagining Legal Responses to Nonconsensual Condom Removal". Columbia Journal of Gender and Law. 32 (2). SSRN 2954726.

- ^ Michael N (27 April 2017). "Some call it 'stealthing,' others call it sexual assault". CNN.

- ^ Davis KC, Danube CL, Neilson EC, Stappenbeck CA, Norris J, George WH, Kajumulo KF (January 2016). "Distal and Proximal Influences on Men's Intentions to Resist Condoms: Alcohol, Sexual Aggression History, Impulsivity, and Social-Cognitive Factors". AIDS and Behavior. 20 (Suppl 1): S147–S157. doi:10.1007/s10461-015-1132-9. PMC 4706816. PMID 26156881.

- ^ Davis KC (October 2010). "The influence of alcohol expectancies and intoxication on men's aggressive unprotected sexual intentions". Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 18 (5): 418–428. doi:10.1037/a0020510. PMC 3000798. PMID 20939645.

- ^ "Njemačke žene nisu silovali samo sovjetski vojnici" [German women were not only raped by Soviet soldiers]. Deutsche Welle (in Croatian). Retrieved 2022-07-02.

- ^ "Rule 93. Rape and other forms of sexual violence are prohibited". International Humanitarian Law (IHL) Databases. International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

- ^ "England gets a taste for Buckfast, the fortified wine that's linked to crime". The Daily Telegraph. 17 July 2017.

- ^ "Alcohol-Related Crimes: Statistics and Facts". Alcohol Rehab Guide. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ^ "Alcohol statistics". Alcohol Change UK. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ Naimi TS, Xuan Z, Cooper SE, Coleman SM, Hadland SE, Swahn MH, Heeren TC (December 2016). "Alcohol Involvement in Homicide Victimization in the United States". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 40 (12): 2614–2621. doi:10.1111/acer.13230. PMC 5134733. PMID 27676334.

- ^ Dingwall G (23 July 2013). Alcohol and Crime. Routledge. pp. 160–161. ISBN 978-1-134-02970-9.

- ^ "Application to Include Fomepizole on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines" (PDF). November 2012. p. 10.

- ^ a b Vale A (2007). "Methanol". Medicine. 35 (12): 633–4. doi:10.1016/j.mpmed.2007.09.014.

- ^ "Methanol Poisoning Overview". Antizol. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 11 October 2011. dead link

- ^ "Methanol (CASRN 67–56–1)". Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Mathurin-2009was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Standridge JB, Zylstra RG, Adams SM (July 2004). "Alcohol consumption: an overview of benefits and risks". Southern Medical Journal. 97 (7): 664–672. doi:10.1097/00007611-200407000-00012. PMID 15301124. S2CID 26801239.

- ^ Kuntsche E, Rehm J, Gmel G (July 2004). "Characteristics of binge drinkers in Europe". Social Science & Medicine. 59 (1): 113–127. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.009. PMID 15087148.

- ^ Clark DB, Bukstein O, Cornelius J (2002). "Alcohol use disorders in adolescents: epidemiology, diagnosis, psychosocial interventions, and pharmacological treatment". Paediatric Drugs. 4 (8): 493–502. doi:10.2165/00128072-200204080-00002. PMID 12126453. S2CID 30900197.

- ^ Floyd RL, O'Connor MJ, Sokol RJ, Bertrand J, Cordero JF (November 2005). "Recognition and prevention of fetal alcohol syndrome". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 106 (5 Pt 1): 1059–1064. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.537.7292. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000181822.91205.6f. PMID 16260526.

- ^ Compare: Stolle M, Sack PM, Thomasius R (May 2009). "Binge drinking in childhood and adolescence: epidemiology, consequences, and interventions". Deutsches Arzteblatt International. 106 (19): 323–328. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2009.0323. PMC 2689602. PMID 19547732.

Excessive episodic consumption of alcohol is usually referred to these days as 'binge drinking.'

- ^ Sher KJ, Grekin ER (2007). "Alcohol and affect regulation.". In Gross JJ (ed.). Handbook of Emotion Regulation. New York: Guilford Press. pp. 560–580. ISBN 978-1-60623-354-2.

- ^ Costa RM, Brody S (October 2013). "Immature psychological defense mechanisms are associated with greater personal importance of junk food, alcohol, and television". Psychiatry Research. 209 (3): 535–539. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2013.06.035. PMID 23866675.

- ^ Konno Y, Okawara M, Hino A, Nagata T, Muramatsu K, Tateishi S, Tsuji M, Ogami A, Yoshimura R, Fujino Y, et al. (Project CORoNaWork) (December 2022). "Association of alcohol consumption and frequency with loneliness: A cross-sectional study among Japanese workers during the COVID-19 pandemic". Heliyon. 8 (12): e11933. Bibcode:2022Heliy...811933K. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11933. PMC 9729165. PMID 36510560.

- ^ Gutkind S, Gorfinkel LR, Hasin DS (January 2022). "Prospective effects of loneliness on frequency of alcohol and marijuana use". Addictive Behaviors. 124: 107115. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107115. PMC 8511227. PMID 34543868.

- ^ Marano H. "The Dangers of Loneliness". Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ^ Trub L, Doyle KM, Parker V, Starks TJ (2021). "Drunk Texting: When the Phone Becomes a Vehicle for Emotional Dysregulation and Problematic Alcohol Use". Substance Use & Misuse. 56 (12): 1815–1824. doi:10.1080/10826084.2021.1954027. PMID 34353214.

- ^ a b Garcia C, Reiber SG, Massey AM (February 2013). "Sexual Hook-up Culture". Monitor on Psychology. Vol. 44, no. 2. American Psychological Association. p. 60. Retrieved 2013-06-04.

- ^ Fielder RL, Carey MP (October 2010). "Predictors and consequences of sexual "hookups" among college students: a short-term prospective study". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 39 (5): 1105–1119. doi:10.1007/s10508-008-9448-4. PMC 2933280. PMID 19130207.

- ^ Lewis MA, Granato H, Blayney JA, Lostutter TW, Kilmer JR (October 2012). "Predictors of hooking up sexual behaviors and emotional reactions among U.S. college students". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 41 (5): 1219–1229. doi:10.1007/s10508-011-9817-2. PMC 4397976. PMID 21796484.

- ^ Freitas D (2013). The End of Sex: How Hookup Culture is Leaving a Generation Unhappy, Sexually Unfulfilled, and Confused About Intimacy. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00215-3.

- ^ Paul EL, McManus B, Hayes A (2000). "'Hookups': Characteristics and Correlates of College Students' Spontaneous and Anonymous Sexual Experiences". Journal of Sex Research. 37 (1): 76–88. doi:10.1080/00224490009552023.

- ^ Santelli JS, Brener ND, Lowry R, Bhatt A, Zabin LS (November 1998). "Multiple sexual partners among U.S. adolescents and young adults". Family Planning Perspectives. 30 (6): 271–275. doi:10.2307/2991502. JSTOR 2991502. PMID 9859017.

- ^ Halpern-Felsher BL, Millstein SG, Ellen JM (November 1996). "Relationship of alcohol use and risky sexual behavior: a review and analysis of findings". The Journal of Adolescent Health. 19 (5): 331–336. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(96)00024-9. PMID 8934293.

- ^ Neilson EC, Marcantonio TL, Woerner J, Leone RM, Haikalis M, Davis KC (March 2024). "Alcohol intoxication, condom use rationale, and men's coercive condom use resistance: The role of past unintended partner pregnancy". Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 38 (2): 173–184. doi:10.1037/adb0000956. PMC 10932814. PMID 37707467.

- ^ Davis KC, Masters NT, Eakins D, Danube CL, George WH, Norris J, Heiman JR (January 2014). "Alcohol intoxication and condom use self-efficacy effects on women's condom use intentions". Addictive Behaviors. 39 (1): 153–158. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.019. PMC 3940263. PMID 24129265.

- ^ Rogow D, Horowitz S (1995). "Withdrawal: a review of the literature and an agenda for research". Studies in Family Planning. 26 (3): 140–153. doi:10.2307/2137833. JSTOR 2137833. PMID 7570764., which cites:

- Population Action International (1991). "A Guide to Methods of Birth Control." Briefing Paper No. 25, Washington, D. C.

- ^ Casey FE (20 March 2024). Talavera F, Barnes AD (eds.). "Coitus interruptus". Medscape.com. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- ^ a b Castles A, Adams EK, Melvin CL, Kelsch C, Boulton ML (April 1999). "Effects of smoking during pregnancy. Five meta-analyses". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 16 (3): 208–215. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00089-0. PMID 10198660. S2CID 33535194.

- ^ a b Eisenberg L, Brown SH (1995). The best intentions: unintended pregnancy and the well-being of children and families. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. pp. 68–70. ISBN 978-0-309-05230-6.

- ^ "Intended and Unintended Births in the United States: 1982–2010" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control. July 24, 2012. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

pmid37310993was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Steinfatt TM (2002). Working at the Bar: Sex Work and Health Communication in Thailand. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 35. ISBN 9781567505672.

- ^ Kishindo P (1995). "Sexual behaviour in the face of risk: the case of bar girls in Malawi's major cities". Health Transition Review. 5 (Supplement: The Third World AIDS Epidemic). National Center for Epidemiology and Population Health (NCEPH), The Australian National University: 153–160. JSTOR 40652159.

- ^ Manthey J, Hassan SA, Carr S, Kilian C, Kuitunen-Paul S, Rehm J (July 2021). "What are the Economic Costs to Society Attributable to Alcohol Use? A Systematic Review and Modelling Study". PharmacoEconomics. 39 (7): 809–822. doi:10.1007/s40273-021-01031-8. PMC 8200347. PMID 33970445.

- ^ Lee GA, Forsythe M (July 2011). "Is alcohol more dangerous than heroin? The physical, social and financial costs of alcohol". International Emergency Nursing. 19 (3): 141–145. doi:10.1016/j.ienj.2011.02.002. PMID 21665157.

- ^ Cheng B, Lim CC, Rutherford BN, Huang S, Ashley DP, Johnson B, Chung J, Chan GC, Coates JM, Gullo MJ, Connor JP (January 2024). "A systematic review and meta-analysis of the relationship between youth drinking, self-posting of alcohol use and other social media engagement (2012–21)". Addiction. 119 (1): 28–46. doi:10.1111/add.16304. PMID 37751678.

- ^ Virtanen M, Jokela M, Nyberg ST, Madsen IE, Lallukka T, Ahola K, Alfredsson L, Batty GD, Bjorner JB, Borritz M, Burr H, Casini A, Clays E, De Bacquer D, Dragano N, Erbel R, Ferrie JE, Fransson EI, Hamer M, Heikkilä K, Jöckel KH, Kittel F, Knutsson A, Koskenvuo M, Ladwig KH, Lunau T, Nielsen ML, Nordin M, Oksanen T, Pejtersen JH, Pentti J, Rugulies R, Salo P, Schupp J, Siegrist J, Singh-Manoux A, Steptoe A, Suominen SB, Theorell T, Vahtera J, Wagner GG, Westerholm PJ, Westerlund H, Kivimäki M (January 2015). "Long working hours and alcohol use: systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies and unpublished individual participant data". BMJ. 350: g7772. doi:10.1136/bmj.g7772. PMC 4293546. PMID 25587065.

- ^ Amiri S (April 2022). "Smoking and alcohol use in unemployed populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Addictive Diseases. 40 (2): 254–277. doi:10.1080/10550887.2021.1981124. PMID 34747337.

- ^ Borsari B, Murphy JG, Barnett NP (October 2007). "Predictors of alcohol use during the first year of college: implications for prevention". Addictive Behaviors. 32 (10): 2062–2086. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.017. PMC 2614076. PMID 17321059.

- ^ Muniz K (24 March 2014). "20 ways Americans are blowing their money". USA Today. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ "Holidaymakers warned over alcohol ban in Ibiza and Majorca". The Independent. 11 May 2024.

- ^ Youssef NA, Rich CL (2008). "Does acute treatment with sedatives/hypnotics for anxiety in depressed patients affect suicide risk? A literature review". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 20 (3): 157–169. doi:10.1080/10401230802177698. PMID 18633742.

- ^ a b Vijayakumar L, Kumar MS, Vijayakumar V (May 2011). "Substance use and suicide". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 24 (3): 197–202. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283459242. PMID 21430536. S2CID 206143129.

- ^ a b Sher L (January 2006). "Alcohol consumption and suicide". QJM. 99 (1): 57–61. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hci146. PMID 16287907.

- ^ Sher L (2007). "Functional magnetic resonance imaging in studies of the neurobiology of suicidal behavior in adolescents with alcohol use disorders". International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. 19 (1): 11–18. doi:10.1515/ijamh.2007.19.1.11. PMID 17458319. S2CID 42672912.

- ^ Janssen MM, Mathijssen JJ, van Bon-Martens MJ, van Oers HA, Garretsen HF (June 2013). "Effectiveness of alcohol prevention interventions based on the principles of social marketing: a systematic review". Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 8 (1): 18. doi:10.1186/1747-597X-8-18. PMC 3679782. PMID 23725406.

- ^ World Health Organization (2014). "Global status report on alcohol and health 2014" (PDF). www.who.int. Retrieved 2015-04-17.

- ^ "Redefine alcohol: WHO's urgent call for Europe to rethink alcohol's place in society". www.who.int.

- ^ "What Is Intermittent Sobriety—and Why Is Everyone Talking About It Right Now?". Real Simple.

- ^ "Are You Trying 'Sober October'? Experts Reveal the Surprising Benefits of 'Intermittent Sobriety'". Health.

- ^ Goddiksen MK (4 January 2023). "Sober Curious er det nye sort'" [Sober Curious is the new kind] (in Danish).

- ^ "What Does It Mean to Be Sober Curious?". Henry Ford Health. 21 March 2023.

- ^ Boesen EG (February 2023). "Skål – uden alkohol". Samvirke (in Danish). pp. 18–27. ISSN 0036-3944.

- ^ Kilian C, O'Donnell A, Potapova N, López-Pelayo H, Schulte B, Miquel L, Paniello Castillo B, Schmidt CS, Gual A, Rehm J, Manthey J (May 2022). "Changes in alcohol use during the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe: A meta-analysis of observational studies". Drug and Alcohol Review. 41 (4): 918–931. doi:10.1111/dar.13446. PMC 9111882. PMID 35187739.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

WHOwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "What We Eat in America, NHANES 2013–2014" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-24. Retrieved 2021-09-29.

- ^ Zhao J, Stockwell T, Naimi T, Churchill S, Clay J, Sherk A (March 2023). "Association Between Daily Alcohol Intake and Risk of All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-analyses". JAMA Network Open. 6 (3): e236185. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.6185. PMC 10066463. PMID 37000449.

- ^ Carr T, Kilian C, Llamosas-Falcón L, Zhu Y, Lasserre AM, Puka K, Probst C (March 2024). "The risk relationships between alcohol consumption, alcohol use disorder and alcohol use disorder mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Addiction. 119 (preprint): 1174–1187. doi:10.1111/add.16456. PMC 11156554. PMID 38450868.

- ^ Babor T, Caetano R, Casswell S, Edwards G, Giesbrecht N, Graham K, Grube J, Hill L, Holder H, Homel R (2010). Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity: Research and Public Policy (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-955114-9. OCLC 656362316.

- ^ Pinquart M (January 2024). "Change in Alcohol Consumption in Adolescence and Emerging Adulthood: A Meta-Analysis". Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 85 (1): 41–50. doi:10.15288/jsad.22-00370. PMID 37650841.

- ^ a b Dunbar RI, Launay J, Wlodarski R, Robertson C, Pearce E, Carney J, MacCarron P (June 2017). "Functional Benefits of (Modest) Alcohol Consumption". Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology. 3 (2): 118–33. doi:10.1007/s40750-016-0058-4. PMC 7010365. PMID 32104646.

- ^ Sayette MA, Creswell KG, Dimoff JD, Fairbairn CE, Cohn JF, Heckman BW, Kirchner TR, Levine JM, Moreland RL (August 2012). "Alcohol and group formation: a multimodal investigation of the effects of alcohol on emotion and social bonding". Psychological Science. 23 (8): 869–78. doi:10.1177/0956797611435134. PMC 5462438. PMID 22760882.

- ^ Druffner N, Egan D, Ramamurthy S, O'Brien J, Davis AF, Jack J, Symester D, Thomas K, Palka JM, Thakkar VJ, Brown ES (May 2024). "IQ in high school as a predictor of midlife alcohol drinking patterns". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 59 (4). doi:10.1093/alcalc/agae035. PMID 38804536.

- ^ "Higher IQ in High School Linked to Increased Alcohol Use in Adulthood". Neuroscience News. 11 October 2024.

- ^ Ruthven M (1997). Islam: a very short introduction. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-154011-0. OCLC 43476241.

- ^ Gentry K (2001). God Gave Wine. Oakdown. pp. 3ff. ISBN 0-9700326-6-8.

- ^ "7b". Megillah (Talmud).

Rava said: A person is obligated to become intoxicated with wine on Purim until he is so intoxicated that he does not know how to distinguish between cursed is Haman and blessed is Mordecai.

- ^ Borras L, Khazaal Y, Khan R, Mohr S, Kaufmann YA, Zullino D, Huguelet P (December 2010). "The relationship between addiction and religion and its possible implication for care". Substance Use & Misuse. 45 (14): 2357–2410. doi:10.3109/10826081003747611. PMC 4137975. PMID 21039108.

- ^ "Drinking on Purim". aishcom. 28 February 2015.

- ^ Zanders ED (2011). "Introduction to Drugs and Drug Targets". The Science and Business of Drug Discovery. pp. 11–27. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-9902-3_2. ISBN 978-1-4419-9901-6. PMC 7120710.

- ^ Room R (2007). "National Variations in the use of Alcohol and Drug Research: Notes of an itinerant worker". Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 24 (6): 634–640. doi:10.1177/145507250702400611. ISSN 1455-0725.

- ^ Farrell M (2007). "The alcohol industry: Taking on the public health critics". British Medical Journal. 335 (7621): 671. doi:10.1136/bmj.39337.431667.4E. PMC 1995479.

- ^ WHO | Lexicon of alcohol and drug terms published by the World Health Organization. Who.int (2010-12-09). Retrieved on 2011-09-24.

- ^ Sienkiewicz P (2011). "[Ethyl alcohol and psychoactive drugs in patients with head and trunk injuries treated at the Department of General Surgery, Provincial Hospital in Siedlce]". Annales Academiae Medicae Stetinensis. 57 (1): 96–104. PMID 22593998.

- ^ Odette MM, Porucznik CA, Gren LH, Garland EL (March 2024). "Alcohol consumption and opioid craving among chronic pain patients prescribed long-term opioid therapy". Addictive Behaviors. 150: 107911. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2023.107911. PMID 38039857.

- ^ Sznitman SR, Kolobov T, Bogt TT, Kuntsche E, Walsh SD, Boniel-Nissim M, Harel-Fisch Y (November 2013). "Exploring substance use normalization among adolescents: a multilevel study in 35 countries". Social Science & Medicine. 97: 143–151. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.08.038. PMID 24161099.

- ^ Sellman D, Connor J, Robinson G, Jackson R (September 2009). "Alcohol cardio-protection has been talked up". The New Zealand Medical Journal. 122 (1303): 97–101. PMID 19851424.

- ^ a b c d e Boyle P (7 March 2013). Alcohol: Science, Policy and Public Health. OUP Oxford. pp. 363–. ISBN 978-0-19-965578-6.

- ^ "Getting a drink in Saudi Arabia". BBC News. BBC. 8 February 2001. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ "Can you drink alcohol in Saudi Arabia?". 1 August 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ "13 Countries With Booze Bans". Swifty.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ "Two Iranians Sentenced to Death for Drinking Alcohol, AFP Says – Businessweek". Archived from the original on 28 June 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ^ "Iran to execute two for alcohol: Reports". Archived from the original on 25 June 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ^ Zhao J, Stockwell T, Vallance K, Hobin E (March 2020). "The Effects of Alcohol Warning Labels on Population Alcohol Consumption: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis of Alcohol Sales in Yukon, Canada". Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 81 (2): 225–37. doi:10.15288/jsad.2020.81.225. PMID 32359054. S2CID 218481829.

- ^ "Alcohol labelling: A discussion document on policy options" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ "Minimum alcohol unit price in Scotland to rise to 65p". 8 February 2024.

- ^ a b "2019 AICR Cancer Risk Awareness Survey" (PDF). AICR 2019 Cancer Risk Awareness Survey. 2019.

- ^ Greene NK, Rising CJ, Seidenberg AB, Eck R, Trivedi N, Oh AY (May 2023). "Exploring correlates of support for restricting breast cancer awareness marketing on alcohol containers among women". The International Journal on Drug Policy. 115: 104016. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2023.104016. PMC 10593197. PMID 36990013.

- ^ Atkinson AM, Meadows BR, Sumnall H (February 2024). "'Just a colour?': Exploring women's relationship with pink alcohol brand marketing within their feminine identity making". The International Journal on Drug Policy. 125: 104337. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2024.104337. PMID 38335868.

- ^ Hall MG, Lee CJ, Jernigan DH, Ruggles P, Cox M, Whitesell C, Grummon AH (May 2024). "The impact of "pinkwashed" alcohol advertisements on attitudes and beliefs: A randomized experiment with US adults". Addictive Behaviors. 152: 107960. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2024.107960. PMC 10923020. PMID 38309239.

- ^ Mart S, Giesbrecht N (October 2015). "Red flags on pinkwashed drinks: contradictions and dangers in marketing alcohol to prevent cancer". Addiction. 110 (10): 1541–1548. doi:10.1111/add.13035. PMID 26350708.

- ^ Spivey JD, Lee JG, Smallwood SW (February 2018). "Tobacco Policies and Alcohol Sponsorship at Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Pride Festivals: Time for Intervention". American Journal of Public Health. 108 (2): 187–188. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.304205. PMC 5846596. PMID 29320286.

- ^ Adams J, Asiasiga L, Neville S (October 2023). "The alcohol industry-A commercial determinant of poor health for Rainbow communities". Health Promotion Journal of Australia. 34 (4): 903–909. doi:10.1002/hpja.665. PMID 36103136.

- ^ "AUDIT The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test" (pdf). WHO (2nd ed.). 2001. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- ^ Kalinowski A, Humphreys K (July 2016). "Governmental standard drink definitions and low-risk alcohol consumption guidelines in 37 countries". Addiction. 111 (7): 1293–1298. doi:10.1111/add.13341. PMID 27073140.