Alcohol packaging warning messages

Alcohol packaging warning messages (alcohol warning labels, AWLs[1]) are warning messages that appear on the packaging of alcoholic drinks concerning their health effects. They have been implemented in an effort to enhance the public's awareness of the harmful effects of consuming alcoholic beverages, especially with respect to foetal alcohol syndrome and alcohol's carcinogenic properties.[2] In general, warnings used in different countries try to emphasize the same messages (see By country). Such warnings have been required in alcohol advertising for many years, although the content of the warnings differ by nation.

A World Health Organization report, published in 2017, stated:[3]

Alcohol product labelling could be considered as a component of a comprehensive public health strategy to reduce alcohol-related harm. Adding health labels to alcohol containers is an important first step in raising awareness and has a longer-term utility in helping to establish a social understanding of the harmful use of alcohol.

A 2014 study in BMC Public Health concluded that "Cancer warning statements on alcoholic beverages constitute a potential means of increasing awareness about the relationship between alcohol consumption and cancer risk."[4]

In many countries, alcoholic beverage packages are not required to have the information about energy and nutritional content required of all other foods and drinks, as of 2018[update].[5]

History

[edit]Increasing calls for the introduction of warning labels on alcoholic beverages have occurred after tobacco packaging warning messages proved successful.[4] The addition of warning labels on alcoholic beverages is historically supported by organizations of the temperance movement, such as the Woman's Christian Temperance Union, as well as by medical organisations, such as the Irish Cancer Society.[6][7] The impetus to add alcohol packaging warning messages to containers of alcoholic beverages "reflect[s] a growing evidence base relating to the relationship between alcohol consumption and a range of health problems including cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, overweight and obesity, liver disease, fetal abnormalities, cognitive impairment, mental health problems, and accidental injury".[4] Even light and moderate alcohol consumption increases cancer risk in individuals.[8][9] As of 2014, alcohol warning labels are required in many countries, including Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, France, Guatemala, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, Taiwan, Thailand, and the United States.[4] Modern alcohol advertising promotes alcoholic beverages heavily "as though it was not a toxic substance".[4] The alcohol industry has tried to actively mislead the public about the risk of cancer due to alcohol consumption,[10] in addition to campaigning to remove laws that require alcoholic beverages to have cancer warning labels.[11]

Cancer warnings

[edit]The World Health Organization declared alcohol a Class I carcinogen in 1990. Despite unequivocal scientific evidence, as of 2020[update], only South Korea had AWLs that warned of the link. The alcohol industry has lobbied hard against any measure that could lead to greater public awareness of the link between alcohol and cancer. These include preventing, delaying, and weakening AWL legislation.[12]

Lobbying methods

[edit]Alcohol producers object strongly to warning labels saying that alcohol causes cancer. They object more to warnings that are more graphic and those which are required to be in a prominent position on the bottle; given the choice, they hide the warnings as inconspicuously as possible. Lobbyists generally do not object to legislation requiring warnings about drunk driving, underage drinking, or fetal alcohol syndrome.[5]

Industry has sometimes argued that integrating warnings into the main label is too expensive, and should be banned. They prefer supplementary stick-on labels, with placement to be chosen by manufacturers, so that it does not interfere with the main label or detract from it. They then choose the most inconspicuous placement. Governments have opposed this.[5]

Countermeasures in trade agreements

[edit]The alcohol industry has also taken to using international trade and investment law to slow the implementation of warning labels, introducing provisions into international agreements that forbid some types of warning labels. This allows them to threaten litigation under these international agreements, creating chilling effects. Even if their cases are thrown out, litigating in national, international, and supernational forums delays action and makes it much more expensive. In 2010, Thai legislation requiring alcohol warning labels was blocked in the World Trade Organization (WTO): alcohol-exporting countries, including Australia, the European Union, New Zealand and the United States, argued that a label mandate was a "technical barrier to trade". Since then, there has been similar WTO opposition to warning labels proposed by Kenya, India, Ireland, Israel, Korea, Mexico, South Africa and Turkey.[5][12]

These tactics have previously been used by the tobbacco industry to oppose tobbacco warning labels and plain packaging requirements. The tobacco industry has lost some lawsuits, but Australia had to fight litigation to the highest Australian court, and before the World Trade Organization, and before an international tribunal. Uruguay, facing litigation from companies richer than it is, was only able to fight industry lawsuits and persist with its warning labelling legistaion by using charitable funding from the Bloomberg Foundation. A lawsuit blocked the introduction of graphic warning labels in the US in 2013, following a ruling from the Court of Appeals for the DC circuit.[5] As of 2023[update], the US still has only the small black-and-white plain-text warnings mandated by the 1988 Alcoholic Beverage Labeling Act. These do not reflect medical research done since 1988.

By country

[edit]Australia

[edit]In Australia, "Alcohol beverage makers must label their products with warning labels relating to the risks of drinking during pregnancy", as of 2019[13]

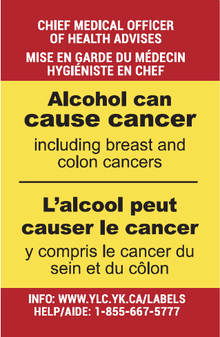

Canada

[edit]In 2017, "Alcohol can cause cancer" warning labels were added to alcoholic products at a liquor store in Yellowknife, next to existing federally-mandated 1991 warnings (about drinking while pregnant, or driving drunk). The labels were added as part of the Northern Territories Alcohol Labels Study, planned to run for eight months. Alcohol industry lobbyists stopped the study after only a few weeks, threatening to sue the Yukon government. Spirits Canada, Beer Canada and the Canadian Vintners Association alleged that the Yukon government had no legislative authority to add the labels, and would be liable for defamation, damages for lost sales, and packaging trademark and copyright infringement, because the labels had been added without their consent.[14][15]

Ireland

[edit]Backed by the Irish Cancer Society, the government of Ireland will place warning labels on alcoholic beverages, with regard to alcohol's carcinogenic properties.[7][16] The policy should enter into force on May 22, 2026.[17]

Thailand

[edit]Alcoholic beverages may not be advertised in a manner which directly or indirectly claims benefits or promotes its consumption, and may not show the product or its packaging.[18] All advertisements must also be accompanied by one out of five predefined warning messages, lasting at least two seconds for video advertisements or occupying at least 25 percent of the advertisement area for print media.[19]

United States

[edit]Since 1989, in the United States, warning labels on alcoholic beverages are currently required to warn "of the risks of drinking and driving, operating machinery, drinking while pregnant, and other general health risks."[20]

As of 2014, the current alcoholic warning message reads as follows:[4]

GOVERNMENT WARNING:

(1) According to the Surgeon General, women should not drink alcohol beverages during pregnancy because of the risk of birth defects.

(2) Consumption of alcoholic beverages impairs your ability to drive a car or operate machinery, and may cause health problems.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Zhao, Jinhui; Stockwell, Tim; Vallance, Kate; Hobin, Erin (March 2020). "The Effects of Alcohol Warning Labels on Population Alcohol Consumption: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis of Alcohol Sales in Yukon, Canada". Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 81 (2): 225–237. doi:10.15288/jsad.2020.81.225. PMID 32359054. S2CID 218481829.

- ^ Wayne, O'Connor (27 September 2018). "Alcohol label 'will help prevent cancer' - Harris". Irish Independent.

- ^ "Alcohol labelling: A discussion document on policy options" (PDF). World Health Organization.

- ^ a b c d e f Pettigrew, Simone; Jongenelis, Michelle; Chikritzhs, Tanya; Slevin, Terry; Pratt, Iain S; Glance, David; Liang, Wenbin (3 August 2014). "Developing cancer warning statements for alcoholic beverages". BMC Public Health. 14 (1): 786. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-786. PMC 4133604. PMID 25087010.

- ^ a b c d e O’Brien, Paula; Gleeson, Deborah; Room, Robin; Wilkinson, Claire (1 May 2018). "Commentary on 'Communicating Messages About Drinking': Using the 'Big Legal Guns' to Block Alcohol Health Warning Labels". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 53 (3): 333–336. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agx124. PMID 29346576.

- ^ Chandler, Ellen (2012). "FASD - Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder". White Ribbon Signal. 117 (2): 2.

- ^ a b Finn, Christina. "Irish Cancer Society urges minister not to drop proposed cancer warning labels on alcohol products". TheJournal.ie.

- ^ Cheryl Platzman Weinstock (8 November 2017). "Alcohol Consumption Increases Risk of Breast and Other Cancers, Doctors Say". Scientific American. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

The ASCO statement, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, cautions that while the greatest risks are seen with heavy long-term use, even low alcohol consumption (defined as less than one drink per day) or moderate consumption (up to two drinks per day for men, and one drink per day for women because they absorb and metabolize it differently) can increase cancer risk. Among women, light drinkers have a four percent increased risk of breast cancer, while moderate drinkers have a 23 percent increased risk of the disease.

- ^ Noelle K. LoConte; Abenaa M. Brewster; Judith S. Kaur; Janette K. Merrill & Anthony J. Alberg (7 November 2017). "Alcohol and Cancer: A Statement of the American Society of Clinical Oncology". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 36 (1).

Clearly, the greatest cancer risks are concentrated in the heavy and moderate drinker categories. Nevertheless, some cancer risk persists even at low levels of consumption. A meta-analysis that focused solely on cancer risks associated with drinking one drink or fewer per day observed that this level of alcohol consumption was still associated with some elevated risk for squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus (sRR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.09 to 1.56), oropharyngeal cancer (sRR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.06 to 1.29), and breast cancer (sRR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.08), but no discernable associations were seen for cancers of the colorectum, larynx, and liver.

- ^ Petticrew M, Maani Hessari N, Knai C, Weiderpass E, et al. (2018). "How alcohol industry organisations mislead the public about alcohol and cancer" (PDF). Drug and Alcohol Review. 37 (3): 293–303. doi:10.1111/dar.12596. PMID 28881410. S2CID 892691.[1]

- ^ Chaudhuri, Saabira (9 February 2018). "Lawmakers, Alcohol Industry Tussle Over Cancer Labels on Booze". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ a b Stockwell, Tim; Solomon, Robert; O’Brien, Paula; Vallance, Kate; Hobin, Erin (March 2020). "Cancer Warning Labels on Alcohol Containers: A Consumer's Right to Know, a Government's Responsibility to Inform, and an Industry's Power to Thwart". Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 81 (2): 284–292. doi:10.15288/jsad.2020.81.284. PMID 32359059. S2CID 218481696.

- ^ "Mandatory warning labels to be introduced on alcohol". Food & Drink Business. 15 October 2018.

- ^ Windeyer, Chris (9 May 2020). "Booze industry brouhaha over Yukon warning labels backfired, study suggests". CBC News. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- ^ "Liquor industry calls halt to cancer warning labels on Yukon booze". CBC News. 28 December 2017.

- ^ "Cancer warning labels to be included on alcohol in Ireland, minister confirms". Belfast Telegraph. 26 September 2018.

- ^ Carrol, Rory (2023-05-22). "Ireland to introduce world-first alcohol health labelling policy". The Guardian.

- ^ "Alcohol Control Act B.E. 2551 (2008)" (PDF). The Office of Alcohol Control Committee, Government of Thailand. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ คลอดแล้ว 5 คำเตือนขวดเหล้า. Thai Rath (in Thai). 8 June 2010.

- ^ Boyle, Peter; Boffetta, Paolo; Lowenfels, Albert B.; Burns, Harry; Brawley, Otis (2013). Alcohol: Science, Policy and Public Health. Oxford University Press. p. 391. ISBN 9780199655786.