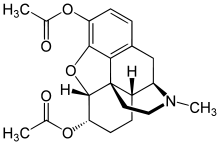

Diacetyldihydromorphine

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Diacetyldihydromorphine, Paralaudin, Dihydroheroin, Acetylmorphinol |

| Routes of administration | Intravenous |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H25NO5 |

| Molar mass | 371.433 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Diacetyldihydromorphine (also known as Paralaudin, dihydroheroin, acetylmorphinol) is a potent opiate derivative developed in Germany in 1928 which is rarely used in some countries for the treatment of severe pain such as that caused by terminal cancer, as another form of diacetylmorphine (also commonly known as Heroin). Diacetyldihydromorphine is fast-acting and longer-lasting than diamorphine, with a duration of action of around 4–7 hours.[1]

As an ester/analogue of dihydromorphine, diacetyldihydromorphine is presumably a Schedule I/Narcotic controlled substance in the United States but does not have its own ACSCN or annual production quota. It does appear in the German Betäubungsmittelgesetz and other European controlled-substances laws.

Diacetyldihydromorphine is quickly metabolized by plasma esterase enzymes into dihydromorphine, in the same way that diamorphine is metabolized into morphine.

Diamorphine is 1.50–1.80 times the potency of morphine.[2]

It shares with other opioids the risk of overdose or (potentially life-threatening) respiratory depression. When strong narcotics are required, and morphine and diamorphine are not an option, it is more common to use better known drugs such as nicomorphine, hydromorphone, levorphanol, oxymorphone or fentanyl which doctors will be more familiar with, and which do not share the stigma associated with either heroin or morphine.[citation needed][dubious – discuss]

Side effects of diacetyldihydromorphine are similar to those of other semi-synthetic opiates and fully synthetic opioids, and the most commonly reported side effects include drowsiness, nausea, and constipation. Compared to morphine, diacetyldihydromorphine produces far fewer side effects which are also often lower in intensity.[citation needed] Though the two drugs are very similar in effects, morphine often produces more intense side effects, including euphoria, constipation, miosis, physical dependence, psychological dependence, potentially life-threatening respiratory depression, and a severe addiction.[citation needed]

Illicit synthesis of dihydroheroin from morphine has been reported, and a "cook" interviewed for a National Geographic documentary on drugs in Vancouver lists it, along with hydromorphone, heroin and 4-methylaminorex (a stimulant) amongst the products he prepares.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ Gilbert AK, Hosztafi S, Mahurter L, Pasternak GW (May 2004). "Pharmacological characterization of dihydromorphine, 6-acetyldihydromorphine and dihydroheroin analgesia and their differentiation from morphine". European Journal of Pharmacology. 492 (2–3): 123–30. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.03.050. PMID 15178355.

- ^ Martin WR, Fraser HF (September 1961). "A comparative study of physiological and subjective effects of heroin and morphine administered intravenously in postaddicts". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 133 (3): 388–99. PMID 13767429.

- ^ "Shooting Up Suburbia". Drugs Inc., Season 7, Episode 20. National Geographic. 5 March 2016. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016.