China and the Russian invasion of Ukraine

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine, China stated that it respects Ukraine's sovereignty but Russia's concerns about enlargement of NATO should also be addressed.[1] It abstained from United Nations votes that condemned the invasion.[2][3] The Chinese government has attempted to mediate between the two countries, but its proposals have faced criticism.[4][5][6] Although China objected to international sanctions against Russia,[7][8] Chinese companies have largely complied with them.[4][3] Drones made by Chinese manufacturers are used by both sides in the conflict. Exports of dual-use technology and component parts from China to Russia have drawn sanctions from the U.S. and condemnation from NATO and the European Union.[9][10][11][12][13] Chinese state media outlets and netizens often gave more weight to Russian state views, sometimes reposting disinformation.[14][15][16]

Chinese government

Only after the invasion began did the Chinese embassy in Ukraine on 25 February advised its citizens to leave the country immediately. On 7 March 2022, the Chinese government stated that it had evacuated most Chinese citizens. Some of the students who had been trapped in Ukraine criticised the embassy's poor response.[17]

On 2 March 2022, The New York Times published an article citing a Western intelligence report which said that the Chinese government had asked the Russian government to delay the invasion until after the 2022 Winter Olympics.[18] The Chinese government denied the allegations, stating that the goal of "this kind of rhetoric is to divert attention and shift blame, which is utterly despicable".[19]

On 15 March 2022, Chinese Ambassador to the United States Qin Gang wrote an op-ed in The Washington Post stating that "conflict between Russia and Ukraine does no good for China", that "the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries, including Ukraine, must be respected; the legitimate security concerns of all countries must be taken seriously", and that "threats against Chinese entities and businesses, as uttered by some U.S. officials, are unacceptable".[20]

On 29 April 2022, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian called China–Russia relations a "new model of international relations" that involved "not causing confrontations or targeting other nations", rising above "the model of military and political alliance in the Cold War era".[21]

Quoting the Russian parliament, The New York Times reported that in September 2022 Li Zhanshu, chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress and the third highest-ranking Politburo Standing Committee member of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), blamed NATO for expanding next to Russia and told a group of Russian legislators that "we fully understand the necessity of all the measures taken by Russia" and that it was placed in an "impossible situation" on the Ukrainian issue.[22] The Wall Street Journal reported that to advance its own interests, Russia has repeatedly leaked information without Chinese knowledge or ahead of China's announcements and decisions. According to people close to China's top decision-makers, had they known about Russia's intention to leak Li's comments, his "choice of words would have been more careful to prevent China from being seen as an accomplice to Russia".[23]

In November 2022, during the 2022 G20 Bali summit, China objected to calling the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine a "war".[24] In the same month, Russia's ambassador to Beijing announced that Xi Jinping would be visiting Moscow, reportedly before China was ready for an announcement. The Wall Street Journal quoted people close to the Chinese leadership saying that the "Chinese side hadn't even made a decision yet".[23]

According to U.S. intercepts of Russian intelligence from the 2022–2023 Pentagon document leaks, Russia believed that China had approved sending "lethal aid" disguised as civilian items. U.S. officials said that they have not yet seen evidence, but have repeatedly warned China against doing so.[25]

On 31 January 2024, during a meeting between admiral Dong Jun and Sergei Shoigu, Dong stated the militaries of Russia and China should be bolstering mutual trust and expanding cooperation to "elevate the relations between the two militaries to a higher level".[26] According to the transcript of the meeting released by the Russian Defense Ministry, Dong stated that China would continue to support Russia on the 'Ukraine issue', and despite pressure from the United States and the European Union, "China will not abandon its established policies and the outside world will not interfere with normal cooperation between China and Russia". When asked about Dong's statements at a press briefing, Foreign Ministry of China spokesperson Wang Wenbin stated that China's position remains unchanged and does not provide military aid to either side of the conflict.[27][28] In February 2024, at the 60th Munich Security Conference, Wang Yi discussed peace prospects with Ukraine's foreign minister and stated that China will not "sell lethal weapons in conflict zones".[29]

In April 2024, the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) reported that a sanctioned Russian ship transferring weapons from North Korea to Russia was moored at a Chinese shipyard in Zhejiang.[30]

Meetings with foreign leaders

On 1 March 2022, the Ukrainian and Chinese foreign ministers, Dmytro Kuleba and Wang Yi, held their first phone call since the beginning of the invasion. Chinese media reported that Wang told Kuleba that he was "extremely concerned" about the risk to civilians and that it was necessary to "ease the situation as much as possible to prevent the conflict from escalating". Kuleba was reported to have said that Ukraine "looks forward to China playing a mediation role in achieving a ceasefire".[31]

On 9 March 2022, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party and Chinese leaderXi Jinping held a video meeting with French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz in which he stated that China was "pained to see the flames of war reignited in Europe" and called for the three countries to promote peace negotiations between Russia and Ukraine.[32] Later that month, Xi Jinping and American President Joe Biden held a two-hour long meeting over video in which the conflict in Ukraine featured significantly. The American White House told the press after the call that Biden had warned Xi of "consequences if China provides material support to Russia".[33]

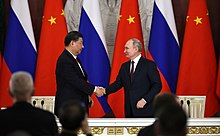

On 20–22 March 2023, Xi Jinping visited Russia and met with Vladimir Putin, both in an official and unofficial capacity.[34][35]

On 26 April 2023, Xi Jinping made an hour-long call to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.[36] Zelenskyy described the call as "long and meaningful" and stressed "a just and sustainable peace for Ukraine".[36]

During the Xi Jinping visit to France in May 2024, he said to Emmanuel Macron and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen that Beijing did not intend to supply weapons to Moscow and that it was ready to look into the issue of dual-use materials that enabled Russia's war effort.[37]

In May 2024, Putin visited China and met with Xi Jinping. The purpose of the visit was to deepen the strategic partnership between Russia and China.[38]

On 23 July 2024, the Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba visited China for the first time since the Russian invasion for talks with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi on ways to achieve a diplomatic solution to the war.[39][40][41]

United Nations votes

On 25 February 2022, China abstained from a United Nations Security Council vote denouncing the invasion.[42] On 2 March 2022, China joined 35 countries in abstaining from a United Nations General Assembly resolution which condemned Russia's aggression and demanded Russia's "immediate, thorough, and unconditional" withdrawal of troops from Ukraine.[43] In December 2023, China voted against condemning Russia at the United Nations.[44]

Peace proposals

On 24 February 2023, China issued a twelve-point peace plan outline, calling for a cease fire and peace talks.[45] The same day, Zelenskyy indicated he was willing to consider aspects of the proposal,[46] while Russia's foreign ministry stated that it welcomed the Chinese proposal.[47] Zelenskyy stated that he planned to meet Xi Jinping because it would be useful to both countries and global security.[46] Vladimir Putin's spokesperson Dmitry Peskov said "we paid a lot of attention to our Chinese friends' plan", but new "territorial realities could not be ignored" as these realities became "an internal factor" (for Russia). Peskov then rejected the Chinese peace proposal, saying that "for now, we don't see any of the conditions that are needed to bring this whole story towards peace".[48] U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken questioned China's peace proposal,[49] saying "the world should not be fooled by any tactical move by Russia, supported by China or any other country, to freeze the war on its own terms".[50]

During the 2023 Belarus-China summit, Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko and Xi jointly stated "deep concern about the development of the armed conflict in the European region and extreme interest in the soonest possible establishment of peace in Ukraine[.]"[51]

In June 2023, China's envoy to Ukraine Li Hui urged all parties to respect territorial integrity, stop arming the battlefield, and ensure the safety of nuclear facilities.[52]

Following the 2023 Shangri-La Dialogue, Ukrainian Defense Minister Oleksii Reznikov said that the peace plans presented by other countries such as China were attempts to mediate on behalf of Russia and that Ukraine is willing to accept a mediator only if the Russians can be convinced to withdraw from all Ukrainian territories.[5][53]

China's 12-point peace plan was presented during a 42-nation peace discussion on 5 August 2023 at Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, and live feedback was received.[54]

In early May 2024, China's designated envoy on the Russian-Ukrainian conflict had visited neutral nations of the Global South like Brazil, Indonesia, Turkey, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, South Africa, and Kazakhstan.[55]

On 23 May 2024, China presented a new six-point peace plan, but according to critics, including Zelenskyy, Russia called on China to undermine the June 2024 Ukraine peace summit in Switzerland.[56][57] According to sources, Chinese diplomats told developing countries that the peace summit in Switzerland would prolong the war, but did not directly ask any country to abstain from the meeting.[57] The six-point proposal by China and Brazil called for an international peace conference "held at a proper time that is recognised by both Russia and Ukraine, with equal participation of all parties as well as fair discussion of all peace plans".[6]

In June 2024, Former Thai Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva said that because of the fundamental lack of trust between the United States and China, and their allies, "it's so difficult to see how either side can claim legitimacy to initiate some kind of peace summit. The other side is simply not going to accept it."[58] On 14 June 2024, China's deputy permanent representative to the United Nations, Geng Shuang, called "on the parties to the conflict to demonstrate political will, come together, and start peace talks as soon as possible to achieve a ceasefire and halt military actions".[59]

In September 2024, Zelenskyy called a peace plan proposed by China and Brazil "destructive" and "just a political statement".[60]

State media

The coverage of the Russian invasion of Ukraine by mainland Chinese media has raised some controversies. The European External Action Service stated that "Chinese state-controlled media and official social media channels have amplified selected pro-Kremlin conspiracy narratives".[61] BBC and CNN believe that discussions of the topic in mainland China are led by Chinese state media outlets, including Global Times, China Central Television (CCTV), and People's Daily.[62][16] The journalistic integrity of these outlets has been called into question. As an example, it was suspected that two days before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Horizon News, the international relations subsection of The Beijing News, accidentally released an internal notice publicly on its official Weibo account. The internal notice included censorship guidelines that demanded the restriction of content that is "unfavourable to Russia" and "pro-West".[63] On the same day, an article on the Global Times website referred to Donetsk and Luhansk as "two nations". The article was later retracted as mainland Chinese media began to collectively refer to the two areas as "regions".[64] On the day Russia launched its military operation against Ukraine, the Communist Youth League of China posted a rendition of the Soviet patriotic song "Katyusha" in Mandarin on its official bilibili account. Initium Media saw this action as an attempt to sensationalize the military conflict.[65]

Several media outlets believe that Chinese media undertook selective reporting. Deutsche Welle and CNN questioned the avoidance of words such as "invasion" and "attack", and the bias towards information from Russian officials, as well as the promotion of anti-U.S. sentiments within China.[16][66][67] However, The Wall Street Journal believes that Chinese state-run media outlets were exercising restraint in their coverage of the conflict, an indication of the cautious stance taken by the Chinese government.[68] Radio France Internationale believes that while China has not condemned Russia's invasion, it does not encourage its citizens to support Ukrainians, and has not openly supported Russia.[69]

On 4 March, CCTV started the live broadcast of the opening ceremony of the 2022 Paralympic Winter Games, which was held in Beijing. During the broadcast, the chairman of the International Paralympic Committee Andrew Parsons mentioned the conflict in a speech made in English, harshly condemning the invasion and calling for peace. CCTV muted this segment of the speech, and did not release a complete translation.[69][70] A shot of 20 Ukrainian athletes applauding and calling for peace was also removed.[71] The International Paralympic Committee believed that censorship took place and demanded an explanation from CCTV.[72]

As of early March, journalist Lu Yuguang of state-run Phoenix Television was the only foreign correspondent to have been embedded with frontline Russian forces.[73]

When covering the Bucha massacre, some Chinese state media promoted unsubstantiated Russian claims that it was staged, seemingly contradicting official statements from China's foreign ministry, which called the images from Bucha "disturbing".[74][75] They reported on the massacre selectively or qualified it as an allegation made by Ukraine or the United States.[75] On 5 April, CCTV-4 relayed the Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov's claim that the Bucha massacre is fake news, spread by Ukraine and the West to slander Russia. Chinese state media selectively reported on Ukrainian president Vlodomir Zelensky's survey of the scene of the massacre, but did not report on the horrific nature of the scene and the pleas from local residents. Global Times claimed that the Bucha massacre was a publicity stunt, in which the U.S. was involved.[76] CCTV made a report in the news at noon on 5 April, in line with the Russian side's allegation that the massacre in Bucha was fake, entitled "Russian Foreign Minister: Uncovering the lies of the Bucha case".[77] As of 6 April, state-run Chinese media outlets such as Xinhua News Agency and People's Daily had not reported on the Bucha massacre in detail.[77]

Industry

In January 2023, Bloomberg News reported that the U.S. government confronted the Chinese about their state-owned enterprises providing non-lethal assistance to Russia. The sources declined to discuss any evidence in detail except to say that the assistance stopped short of evading wholesale the sanctions "the US and its allies imposed" after Russia invaded Ukraine. The White House said it was monitoring and reviewing the situation.[78]

In February 2023, The Wall Street Journal reported that according to Russian customs data, Chinese companies have shipped dual-use items such as navigation equipment, jamming technology, and fighter jet parts to Russian state-owned companies.[79] The same month, Der Spiegel reported that Xi'an Bingo Intelligent Aviation Technology was in talks to sell kamikaze drones to Russia.[80] Chinese companies have called the reports inaccurate.[79][80] The New York Times subsequently reported that Poly Technologies sent sufficient quantities of gunpower to the Barnaul Cartridge Plant to make 80 million rounds of ammunition.[12] China is a key supplier of nitrocellulose, a key ingredient for modern gunpowder, to Russia.[81]

In March 2023, Politico reported that between June and December 2022, Chinese companies such as the state-owned Norinco shipped dual-use items, including assault rifles, drone parts, and body armor, to Russian companies, which have also been routing shipments via Middle Eastern countries that have relationships with both Russia and the West.[82][83] U.S. officials stated that according to intelligence gleaned from Russia, China was considering supplying the country with lethal aid. Different American officials expressed varying degrees of confidence in this assessment.[84] The U.S. also said Chinese-made ammunition has been used in Ukraine, although it was unclear who supplied it.[85] Other officials said that they had not seen evidence that China actually supplied arms to Russia. The U.S. statement came at the eve of China's unveiling of its peace plan to stop the war. The Biden administration decided against declassifying any sensitive details of the intelligence report.[84]

In 2023, Izhevsk Electromechanical Plant (IEMZ Kupol) began manufacturing kamikaze drones for the Russian military using Chinese engines and parts.[86] Sources told Reuters that Kupol established a factory in China and delivered seven complete Garpiya-3 drones in early 2024. Chinese officials said they were not aware of the production activity. NATO countries called on China to make sure its companies do not provide lethal assistance to Russia.[87] This demand was also stressed by a representative of the European Union.[88]

DJI drones have been used by both Ukraine and Russia since the invasion.[11] In October 2023, the Ukrainian government announced the purchase of 4,000 DJI drones.[89]

In April 2024, the United States and the United Kingdom announced a ban on imports of Russian aluminum, copper, and nickel.[90] Due to sanctions, Russian nickel, copper and palladium mining and smelting company Norilsk Nickel planned to move some of its copper smelting to China and establish a joint venture with a Chinese company.[91] Finished copper products would be sold as Chinese products to avoid Western sanctions.[92] China is Norilsk Nickel's largest export market from 2023.[93] Nickel is a critical metal in electric vehicle batteries, and palladium is critical element in catalytic converters, a component in natural gas vehicles.[94]

In September 2024, Reuters reported that Russia had established a weapons program in China to develop and produce attack drones for use in the invasion of Ukraine. A subsidiary of Russian state-owned company Almaz-Ante, IEMZ Kupol, said it was able to produce drones with assistance from local specialists, including a newly-developed model, at scale at a Chinese factory for deployment in the war.[87]

Trade

Following the implementation of international sanctions during the Russo-Ukrainian War initiated by the U.S., U.K., European Union and Japan, China said it will not join them.[95][96] China's total trade with Russia was a record $190 billion in 2022.[97] In the same year, China accounted for 40% of Russia's imports.[98] In the first half of 2023, models from Chinese car companies accounted for more than a third of all sales in Russia.[99]

In 2023, China's total trade with Russia reached a record $240 billion.[100] Russia's dependence on the Chinese yuan increased heavily after its invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Yuan's share of stock market trading in Russia increased from 3% to 33%[98] However, by August 2024, Russian transactions with Chinese banks (especially smaller ones) were largely closed.[101] Due to strict secondary sanctions, Russia could not exchange money with China.[102][103] As many as 98% of Chinese banks rejected direct yuan payments from Russia.[104]

Before the invasion, China preferred trade routes that passed through Russia, but due to sanctions it has been warming up to the costlier Middle Corridor, which has received increased investments from adjacent countries in Europe and the Middle East as well.[105]

Civil society

Due to the rise of anti-U.S. sentiments in China in recent years, as well as the bilateral strategic partnership between China and Russia, many netizens in China supported the actions and position taken by the Russian president Vladimir Putin around the beginning of the invasion in 2022. There have also been anti-war and pro-Ukraine voices online, although it has been reported that they have been subjected to attacks from pro-Russia netizens and many such posts had been deleted.[66][106][107][16]

According to Voice of America, a large volume of controversial commentary surfaced on Chinese social media in the early stages of the military conflict between Russia and Ukraine.[108] Coupled with the fact that online discussions are strictly monitored and censored by the state, many believe that Chinese public opinion on the matter is divided, with opposing factions.[109][66]

On one hand, much commentary is in support of Russia, recognizing Russia's concern for national security, and attributing the deterioration of Russia-Ukraine relations to NATO and Western nations such as the U.S.. As a result, these commentators support the military invasion of Ukraine, and even praise the Russian president Vladimir Putin as a heroic figure that dares to challenge the West.[66][106][107]

On the other hand, anti-war figures also exist in mainland China,[65] such as the public figures Jin Xing,[110] Yuan Li, and Ke Lan. Many professors[111] and alumni[112] of institutions, including Peking University and Tsinghua University, also publicly expressed anti-war statements, but these statements have been harshly criticized by netizens, and are censored or deleted on mainland Chinese social media platforms.[113][114][115][116] Chinese company NetEase has published a few videos critical of Russia from Chinese in Ukraine and Ukrainians in China.[117][118]

Some Chinese netizens made inappropriate comments related to "taking in beautiful Ukrainian women", which have been reposted by foreign media.[119][120] The circulation of the translated comments spread to Ukraine, inciting widespread anti-Chinese sentiment and causing Chinese people living there to face local hostility.[121][122] Such comments have also been found on social media in Taiwan, prompting the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) to post an article accusing Taiwan and Xinjiang independence forces of being responsible.[123] Some mainland netizens also promoted Chinese unification with Taiwan by force in their discussions of the Russian invasion.[68] In response, Chinese state-run media outlet The Paper urged the public to comment on the war rationally, and not to become "vulgar bystanders".[124] Social media platforms in China such as Douyin and Weibo also began deleting posts containing the offending content, with Weibo announcing bans for users posting such content.[123][125]

On 26 February 2022, five Chinese historians signed an open letter opposing the invasion, stating that "great catastrophes in history often started with local conflicts". However, the letter was removed from the Internet by Chinese censors after three hours.[126]

Hong Kong has somewhat different reactions to the Russian invasion from that in mainland China.[127]

On 5 March, Hu Wei, the vice-chairman of the Public Policy Research Center of the Counsellors' Office of the State Council, wrote an article arguing that "China needs to respond flexibly and make strategic choices that conform to its long-term interests" and that "China cannot be tied to Putin and needs to be cut off as soon as possible".[128]

In September 2023, opera singer Wang Fang sparked a diplomatic row after singing the Soviet war song "Katyusha" inside the Donetsk Academic Regional Drama Theater in Mariupol where hundreds were killed in 2022.[129] Wang was part of a group of Chinese bloggers illegally visiting the Ukrainian city. Oleg Nikolenko, spokesman for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, said that "the performance of the song "Katyusha" by Chinese 'opera singer' Wang Fan on the ruins of the Mariupol Drama Theater, where the Russian army killed more than 600 innocent people, is an example of complete moral degradation".[130] Nikolenko further stated that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine would ban the group of bloggers from entering Ukraine and would expects the Chinese side to explain the purpose of the Chinese citizens' stay in Mariupol, as well as the way they entered the temporarily occupied Ukrainian city.[131][132] The New York Times reported that the video of Wang and news about it were promptly removed from the Chinese internet.[133]

Opinion polling

According to a survey conducted by Blackbox Research in March 2022, 71% of respondents from China expressed more sympathy for Ukraine over Russia and 3% expressed more sympathy for Russia.[134] According to a survey published by the US-China Perception Monitor in April 2022, 75% of online Chinese respondents said they agreed or strongly agreed that supporting Russia in the conflict was in China's national interest.[135]

According to a Genron NPO poll released in November 2022 on Chinese peoples' views of the Russian invasion, 39.5% of respondents said the Russian actions "are not wrong", 21.5% said "the Russian actions are a violation of the U.N. Charter and international laws, and should be opposed", and 29% said "the Russian actions are wrong, but the circumstances should be considered".[136][137]

According to a February 2023 poll conducted by Morning Consult, 49% of Chinese adults said that Beijing should stay neutral in the Ukraine conflict, 12% said Beijing should use its influence to persuade Russia to end its military operations, 9% said they supported supplying strategic intelligence to Russia, and 7% supported sending weapons. The youngest Chinese adults generally expressed the least interest in lending support to Russia.[138]

International reactions

European Union

In May 2023, European Union (EU) officials reportedly criticized China's peace plan as an attempt at "freezing" the conflict in place and splitting the West in pushing Ukraine cease-fire.[139] The European Union plans to sanction companies in mainland China, Turkey, India, and Serbia for aiding Russia in circumventing sanctions, targeting entities supplying dual-use goods. Despite concerns, this marks the first time the EU openly targets Chinese companies for sanctions, with diplomats aiming to finalize the plan by the end February 2024.[140] In November 2024, Kaja Kallas stated that China must pay a "higher cost" for its support of Russia.[141] The EU has been critical of Chinese military drones produced for Russia.[142]

NATO

On 23 March 2022, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg accused China of providing political support to Russia, "including by spreading blatant lies and misinformation", and expressed concern that "China could provide material support for the Russian invasion".[143]

In May 2024, Stoltenberg stated that "Russia would not have been able to conduct the war of aggression against Ukraine without the support from China".[144] He warned that China "cannot continue to have normal trade relationships with countries in Europe and at the same time fuel the biggest war we have seen in Europe since the Second World War".[145][146] At the 2024 Washington summit, NATO called on China to cease its support as a "decisive enabler" of Russia's war effort, criticising its "no limits partnership" with Russia and exports of dual-use technology. China said it "does not provide weapons to the parties to the conflict and strictly controls the export of dual-use articles".[13][147] In September 2024, Stoltenberg "call[ed] on China to stop supporting Russia's illegal war".[148]

United Kingdom

In July 2023, Britain's head of MI6, Richard Moore, stated that the Chinese government and Xi Jinping were "absolutely complicit" in the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[149]

In May 2024, former UK defense minister Grant Shapps stated that according to US and British intelligence, "lethal aid" was being flown from China to Russia and into Ukraine.[150] In response, US national security advisor Jake Sullivan stated "we have not seen that to date", but expressed US "concern about what China's doing to fuel Russia's war machine – not giving weapons directly, but providing inputs to Russia’s defence industrial base".[150]

United States

On 9 July 2022, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken questioned China's neutrality and accused China of supporting Russia.[151]

In April 2024, the U.S. has accused China of supplying Russia with geospatial intelligence.[152] In June, Blinken said China's support for Russia's defense industry was prolonging the war.[145]

Ukraine

In May 2022, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said that, "China has chosen the policy of staying away. At the moment, Ukraine is satisfied with this policy."[153]

Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy said that, "without the Chinese market for the Russian Federation, Russia would be feeling complete economic isolation. That's something that China can do – to limit the trade [with Russia] until the war is over." In April 2023, Xi and Zelenskyy held their first direct talks about the war.[154][155]

An opinion poll conducted in February–March 2023 by the Razumkov Centre showed that 60% of Ukrainians surveyed had a negative view of China.[156] Another Razumkov Centre poll conducted from January 19 to January 25, 2024, had 72.5% of Ukrainian respondents expressing a negative view of China, which was only less than 3 other countries: Iran (82%), Belarus (87%), and Russia (95%).[157] 64% expressed a negative view of Xi Jinping in the 2024 poll.[158]

In June 2024, Zelenskyy said China's support for Russia would prolong the war and accused Russia of using Chinese diplomats as part of its efforts to undermine the Ukraine peace summit in Switzerland. China's Foreign Ministry said the country was not against the peace summit and did not exert pressure on other countries.[159]

Sanctions against China

European Union

In May 2023, the European Union discussed placing sanctions on companies from China and five other countries for selling equipment that could be used in weapons by Russia.[160] The Chinese government made a commitment to put pressure on the China-based companies on the list, prompting the EU to temporarily remove five of the eight Chinese companies on the draft list.[161] In January 2024, the EU proposed export bans on three firms in mainland China.[162]

United States

In April 2022, United States Secretary of Treasury Janet Yellen warned China that it could face consequences for not sanctioning Russia.[163] In June 2022, the United States Department of Commerce placed five Hong Kong companies on the Bureau of Industry and Security's Entity List for providing support to Russia's military.[164][165] The U.S. Treasury Department separately sanctioned a Chinese and an Armenian vendor for maintaining trade relationship with a Russian arms procurement firm.[166][167] In September 2022, the Office of Foreign Assets Control sanctioned Sinno Electronics of Shenzhen for supplying a Russian military procurement network.[166][168]

In January 2023, the U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned Spacety China, also known as Changsha Tianyi Space Science and Technology Research Institute Co. Ltd., for providing satellite imagery to the Wagner Group.[169] In February 2023, the U.S. Commerce Department added AOOK Technology Ltd, Beijing Ti-Tech Science and Technology Development Co, Beijing Yunze Technology Co, and China HEAD Aerospace Technology Co to the Entity List for aiding Russia's military.[170][171][172]

In March 2023, the U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned five Chinese companies for supplying equipment to the Iran Aircraft Manufacturing Industries Corporation, which manufactures HESA Shahed 136 drones used by Russia against Ukraine.[173][174]

In July 2023, the US Office of the Director of National Intelligence published a report stating that the Chinese government is assisting Russia to evade sanctions and providing it with dual-use technology.[175][176]

In October 2023, the U.S. Department of Commerce added 42 Chinese companies to the Entity List for supplying Russia with microelectronics for missile and drone guidance systems.[177] In April 2024, the Department of Commerce sanctioned a Chinese company for supporting Russia's military through the procurement, development, and proliferation of Russian drones.[178] In May 2024, the U.S. sanctioned 20 companies in China and Hong Kong for supplying Russia's military.[179] In October 2024, the U.S. sanctioned two companies, Xiamen Limbach Aircraft Engine Co. and Redlepus Vector Industry, involving the production of long-range attack drones for Russia, including the Garpiya.[180]International commentary and analysis

The Economist has stated that China's professed neutrality is "in reality a pro-Russian pseudo-neutrality".[181] Mark Leonard of the European Council on Foreign Relations has stated that "for China, the war in Ukraine simply isn't that important", adding that the war is seen "not as a cataclysmic war that's reshaping the global order, but as a proxy conflict".[182]

Joseph Torigian of the American University described the Chinese government's position on the invasion as a "balancing act", stating that "the governments of both countries hold similarly negative views about America's role in Europe and Asia", but that China would not be willing to put its financial interests at risk to support Russia, especially given that China was "trying to preserve its reputation as a responsible stakeholder".[183] Ryan Hass of the Brookings Institution has argued that "without Russia, the thinking goes, China would be alone to deal with a hostile west determined to obstruct China's rise", but that the two countries "do not have perfectly aligned interests. China has a lot more to lose than Russia. China sees itself as a country on the rise with momentum behind it. Russia is essentially fighting the tides of decline."[184]

Several commentators have foreseen a potential role for China as a key mediator in the conflict. Érick Duchesne of the Université Laval has argued that "strategic ambiguity on the part of China could have a beneficial effect and help untie the Gordian knot of the crisis" and that it would be a "a serious mistake" for NATO countries to oppose Chinese mediation.[185] Zeno Leoni of King's College London argued that "should China lead parties involved to a new peace, it would be a major diplomatic and public relations victory for Beijing", as the Chinese government "would be able to present itself as a responsible great power and to convince the west that in future they might have to rely on Beijing's global influence at a time when US influence is declining".[186]

See also

- United States and the Russian invasion of Ukraine

- Foreign involvement in the Russian invasion of Ukraine

References

- ^ Martina, Michael (February 25, 2022). "China says it respects Ukraine's sovereignty and Russia's security concerns". Reuters.

- ^ Wintour, Patrick (2022-02-27). "Ukraine: what will China do? There are signs it is uneasy about Putin's methods". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Archived from the original on 2022-03-21. Retrieved 2023-06-22.

- ^ a b Bourgeois-Fortin, Camille; Choi, Darren; Janke, Sean (7 March 2022). "China and Russia's invasion of Ukraine: Initial responses and implications". University of Alberta. Archived from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ a b Chestnut Greitens, Sheena (2022-10-21). "China's Response to War in Ukraine". Asian Survey. 62 (5–6): 751–781. doi:10.1525/as.2022.1807273. ISSN 0004-4687. S2CID 253232026.

- ^ a b "Chinese and Indonesian 'peace plans' really just Russia proxies, says DM Reznikov at NV event". The New Voice of Ukraine. 8 June 2023. Archived from the original on 21 June 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ a b Gabuev, Alexander (14 June 2024). "Why China Is Sabotaging Ukraine". Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 19 June 2024. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ "China will not join sanctions on Russia, banking regulator says". Reuters. 2 March 2022. Archived from the original on 2022-03-22. Retrieved 2022-06-05.

- ^ "China rejects 'pressure or coercion' over Russia relations". Associated Press. 14 April 2022. Archived from the original on 14 April 2022. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ "US sanctions Chinese companies for supplying parts used in Iranian drones". Financial Times. 2023-03-09. Archived from the original on 2023-03-22. Retrieved 2023-03-10.

- ^ Nissenbaum, Dion (2023-06-12). "Chinese Parts Help Iran Supply Drones to Russia Quickly, Investigators Say". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 2023-06-19. Retrieved 2023-06-22.

- ^ a b Mozur, Paul; Krolik, Aaron; Bradsher, Keith (2023-03-21). "As War in Ukraine Grinds On, China Helps Refill Russian Drone Supplies". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2023-06-02. Retrieved 2023-03-23.

- ^ a b Swanson, Ana; Ismay, John (2023-06-23). "Chinese Firm Sent Large Shipments of Gunpowder to Russian Munitions Factory". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2023-06-24. Retrieved 2023-06-24.

- ^ a b "NATO allies call China a 'decisive enabler' of Russia's war in Ukraine". Associated Press. 2024-07-10. Archived from the original on 2024-07-10. Retrieved 2024-07-10.

- ^ Repnikova, Maria; Zhou, Wendy (11 March 2022). "What China's Social Media Is Saying About Ukraine". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 17 March 2022. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ Dwoskin, Elizabeth (April 8, 2022). "China is Russia's most powerful weapon for information warfare". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on April 19, 2022. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c d McCarthy, Simone (10 March 2022). "China's promotion of Russian disinformation indicates where its loyalties lie". CNN. Archived from the original on 2022-05-12. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ "'It came too late': Chinese students who fled Ukraine criticise embassy response". The Guardian. March 8, 2022. Archived from the original on March 23, 2022. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ^ Wong, Edward; Barnes, Julian E. (2022-03-02). "China Asked Russia to Delay Ukraine War Until After Olympics, U.S. Officials Say". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2022-03-24. Retrieved 2022-06-22.

- ^ "China denies it asked Russia not to invade Ukraine during Winter Olympics". The Guardian. March 3, 2022. Archived from the original on March 23, 2022. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ^ "Opinion | Chinese ambassador: Where we stand on Ukraine". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 2022-03-23. Retrieved 2022-06-22.

- ^ "China Calls Russia Relationship a 'New Model' for the World". Bloomberg News. 29 April 2022. Archived from the original on 2022-06-03. Retrieved 2022-04-30.

- ^ Ramzy, Austin (2022-09-11). "Russia says that a senior Chinese official expressed support for the invasion of Ukraine". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2022-12-18. Retrieved 2022-09-11.

- ^ a b Wei, Lingling (19 March 2023). "Putin Proves an Unpredictable Partner for Xi as Nations Cement Ties". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ "In G-20 talks, China objects to calling Russian invasion of Ukraine a 'war'". The Washington Post. November 15, 2022. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 2022-11-16. Retrieved 2022-11-15.

- ^ DeYoung, Karen; Ryan, Missy (April 13, 2023). "Russia says China agreed to secretly provide weapons, leaked documents show". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 2023-04-30. Retrieved 2023-04-14.

- ^ Liu, Zhen (2024-02-01). "China's new defence minister urges 'closest' military relations in first talks with Russian counterpart". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 2024-02-03. Retrieved 2024-02-03.

- ^ Shcherbakova, Irina (2024-01-31). "Министр обороны Китая дал обещание Шойгу по поводу Украины". Ura.ua (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 2024-02-05. Retrieved 2024-02-05.

- ^ "Китай прокоментував інформацію про нібито підтримку Росії в "українському питанні"". Ukrinform (in Ukrainian). 2024-02-01. Archived from the original on 2024-02-04. Retrieved 2024-02-05.

- ^ "Ukrainian foreign minister discusses peace prospects with China's Wang Yi". Reuters. February 18, 2024. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ Martina, Michael; Brunnstrom, David (April 25, 2024). "China harbors ship tied to North Korea-Russia arms transfers, satellite images show". Reuters. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ^ "China signals willingness to mediate in Ukraine-Russia war". The Guardian. March 1, 2022. Archived from the original on March 24, 2022. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ^ "China's Xi: Beijing supports peace talks between Russia, Ukraine". Al Jazeera English. Archived from the original on 2022-03-23. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- ^ "Xi tells Biden Russia-Ukraine fighting is in 'no one's interest'". Al Jazeera English. 18 March 2022. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ "Xi, Putin meeting highlights US tensions with China". ABC News. 21 March 2023. Archived from the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ Gan, Nectar (2023-03-20). "Xi makes 'journey of friendship' to Moscow days after Putin's war crime warrant issued". CNN. Archived from the original on 2023-03-21.

- ^ a b "China's Xi calls Ukraine's Zelenskyy, after weeks of intensifying pressure to do so". NPR. 2023-04-26. Archived from the original on 2023-04-26. Retrieved 2023-04-26.

- ^ John Irish; Elizabeth Pineau (2024-05-06). "China's Xi backs Macron call for global Olympic truce". Reuters.

- ^ "Putin's visit to China: Here's what you should know". Euronews. May 16, 2024. Archived from the original on June 4, 2024. Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ^ Stevenson, Alexandra; Méheut, Constant (July 24, 2024). "Ukraine Presses China to Help Seek End to War With Russia". The New York Times. Retrieved October 12, 2024.

- ^ Dysa, Yuliia; Balmforth, Tom (23 July 2024). "Ukraine's foreign minister arrives in China to discuss 'fair peace'". Reuters. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ Zubkova, Daria (24 July 2024). "Just peace in Ukraine corresponds to strategic interests of China - Kuleba". Ukrainian News. Archived from the original on 24 July 2024. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ Nichols, Michelle; Pamuk, Humeyra (February 26, 2022). "Russia vetoes U.N. Security action on Ukraine as China abstains". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2022-02-26. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- ^ 牛弹琴 (March 4, 2022). "联大谴责俄罗斯 为什么这35个国家投了弃权票?" [The UN General Assembly condemns Russia. Why did these 35 countries abstain from voting?]. Phoenix Television. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022.

- ^ "Situation of human rights in the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine, including the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol :: resolution /: adopted by the General Assembly". 2023-12-19.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Wong, Chun Han; Areddy, James T. (2023-02-24). "China Urges End to Ukraine War, Calls for Peace Talks". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 2023-03-11. Retrieved 2023-06-22.

- ^ a b Harding, Luke (2023-02-24). "Zelenskiy open to China's peace plan but rejects compromise with 'sick' Putin". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2023-03-13. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ^ "Russia welcomes China peace plan, says it is open to talks". Reuters. 2023-02-24. Archived from the original on 2023-03-13. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ^ AFP News (27 February 2023). "Kremlin, on China Plan, Says No Conditions for Peace 'At the Moment' in Ukraine". The Moscow Times. Archived from the original on 20 March 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- ^ "Blinken Backs Ukraine's Peace Proposal, Warns Against China's". Bloomberg News. 28 March 2023. Archived from the original on 2024-07-16. Retrieved 2023-04-06.

- ^ Sauer, Pjotr; Davidson, Helen (2023-03-21). "Putin welcomes China's controversial proposals for peace in Ukraine". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2023-04-12. Retrieved 2023-06-22.

- ^ "Xi and Lukashenko call for 'soonest' peace in Ukraine at China-Belarus summit". Reuters. 2023-03-01. Archived from the original on 2023-03-19. Retrieved 2023-03-02.

- ^ McDonald, Joe (2023-06-02). "China Ukraine envoy urges allies to 'stop sending weapons' to Kyiv". Defense News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2024-07-16. Retrieved 2023-06-03.

- ^ Bhagyashree Garekar (5 June 2023). "If Xi gets Putin to send Russia's troops home, he can broker peace: Ukraine Defence Minister". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ Laurence Norman; Stephen Kalin (5 August 2023). "With China Attending, Ukraine Peace Discussions Inch Forward". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 5 August 2023. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ^ "Opinion: Final blow to Chinese 'neutrality' on Ukraine war". Politico. 19 June 2024. Archived from the original on 19 June 2024. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ "Zelensky says China's 'support to Russia' will extend war in Ukraine during surprise appearance in Asia". CNN. 3 June 2024. Archived from the original on 19 June 2024. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Exclusive: China pushes rival Ukraine peace plan before Swiss summit, diplomats say". Reuters. 14 June 2024. Archived from the original on 2024-06-13. Retrieved 2024-06-19.

- ^ "Ukraine Struggles to Court Global South Before Swiss Summit". SWI swissinfo. 14 June 2024. Archived from the original on 19 June 2024. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ "China calls for Russia-Ukraine peace talks 'as soon as possible' after skipping Swiss summit that shunned Moscow". South China Morning Post. 16 June 2024. Archived from the original on 19 June 2024. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ "Ukraine's Zelenskiy dismisses 'destructive' China-Brazil peace initiative". Reuters. September 12, 2024. Retrieved September 12, 2024.

- ^ "1st EEAS Report on Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference Threats". European External Action Service. 7 February 2023. Archived from the original on 2023-02-22. Retrieved 2023-02-22.

- ^ "从历史到现实 中港台三地民众如何观察俄乌之战". BBC News (in Simplified Chinese). Archived from the original on 2022-03-10. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ^ "【烏克蘭危機】官方嚴禁媒體批評俄羅斯 要求嚴控「支持歐美」言論". Radio Free Asia (in Traditional Chinese). Archived from the original on 2022-02-25. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ^ "【烏克蘭危機】中共官媒一度承認烏東親俄地區獨立 後報道刪除改稱「地區」". Radio Free Asia (in Traditional Chinese). Archived from the original on 2022-02-25. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ^ a b "否認「入侵」、信息污染、疑美,烏克蘭危機中港台輿論觀察". Initium Media (in Traditional Chinese). Archived from the original on 2022-12-03. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ^ a b c d "俄烏戰事讓中國網友對立 言論控管痕跡處處 | 兩岸 | 中央社 CNA". Central News Agency (Taiwan) (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2022-03-07. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ "德语媒体:在中国被捧为英雄的普京 | DW | 28.02.2022". Deutsche Welle (in Simplified Chinese). Archived from the original on 2022-10-11. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ^ a b Hua, Sha. "俄罗斯入侵乌克兰之际,中国社交媒体充斥着对西方的嘲讽和对台湾的警告". The Wall Street Journal (in Simplified Chinese). Archived from the original on 2022-08-06. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ^ a b "国际残奥委会对中国电视审查该机构主席开幕式反战讲话提出抗议". Radio France Internationale (in Simplified Chinese). 2022-03-05. Archived from the original on 2022-03-08. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ^ "中国未报道IPC主席的部分冬残奥会开幕致词". NHK. 2023-04-01. Archived from the original on 2022-03-07.

- ^ "Pechino, inaugurate le Paralimpiadi. La tv cinese censura l'appello per la pace in Ucraina". RaiNews (in Italian). 5 March 2022. Archived from the original on 2022-03-05. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ^ "Paralympic Committee asks Beijing why anti-war speech censored". France 24. 2022-03-05. Archived from the original on 2022-03-08. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ^ "'I'm on the frontline in Mariupol': the Chinese reporter embedded with Russian troops". The Guardian. March 16, 2022. Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ^ McCarthy, Simone; Xiong, Yong (6 April 2022). "As the world reacts in horror to Bucha, China's state media strikes a different tone". CNN. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ^ a b Mozur, Paul; Myers, Steven Lee; Liu, John (2022-04-11). "China's Echoes of Russia's Alternate Reality Intensify Around the World". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2022-05-20. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

On Wednesday, Zhao Lijian, a spokesman for China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, called the images from Bucha "disturbing" and asked for all parties to "exercise restraint and avoid groundless accusations."

- ^ "俄軍屠殺烏克蘭平民 中國至今沉默官媒反指炒作 | 兩岸 | 中央社 CNA". www.cna.com.tw (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2022-05-03. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ^ a b "ブチャの虐殺は「フェイク」 中国メディアはロシアの主張が中心". All-Nippon News Network (in Japanese). 2022-04-05. Archived from the original on 2022-04-08. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- ^ Martin, Peter; Leonard, Jenny (January 24, 2023). "US Confronts China Over Companies' Ties to Russian War Effort". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on January 31, 2023. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ^ a b Talley, Ian; DeBarros, Anthony (2023-02-04). "China Aids Russia's War in Ukraine, Trade Data Shows". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 2023-03-12. Retrieved 2023-06-21.

- ^ a b Wong, Alan (24 February 2023). "'No Commercial Contact': Chinese Drone Maker Denies Selling Arms to Russia". Vice News. Archived from the original on 2023-03-12. Retrieved 2023-03-05.

- ^ Northrop, Katrina (2024-07-28). "Gunpowder Gambit". The Wire China. Archived from the original on 2024-07-29. Retrieved 2024-07-29.

- ^ Banco, Eric; Aarup, Sarah Anne (16 March 2023). "'Hunting rifles' — really? China ships assault weapons and body armor to Russia". Politico. Archived from the original on 2023-03-28. Retrieved 2023-03-17.

- ^ Banco, Erin; Overly, Steven (March 28, 2023). "China-linked Russian body armor is landing on the battlefield in Ukraine". Politico. Archived from the original on March 28, 2023. Retrieved March 28, 2023.

- ^ a b Kube, Courtney; Lee, Carol E. (3 March 2023). "U.S. intel on China considering lethal aid for Putin's war was gleaned from Russian officials". CNBC. Archived from the original on 2023-03-16. Retrieved 2023-03-05.

- ^ "Use of Chinese ammunition in Ukraine confirmed by U.S.: sources". Kyodo News. 18 March 2023. Archived from the original on 2023-05-15. Retrieved 2023-03-19.

- ^ Deutsch, Anthony; Balmforth, Tom (September 13, 2024). "Russia produces kamikaze drone with Chinese engine". Reuters. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

- ^ a b "Russia has secret war drones project in China, intel sources say". Reuters. September 25, 2024. Retrieved September 25, 2024.

- ^ "EU concerned by report of Russia producing attack drones in China". Reuters. September 27, 2024. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

It would go against China's official narrative that it does not provide lethal weapons to support Russia in its war of aggression against Ukraine and therefore we expect the allegations to be thoroughly and immediately examined and addressed by the Chinese authorities.

- ^ Gosselin-Malo, Elisabeth (23 October 2023). "Ukraine continues to snap up Chinese DJI drones for its defense". Defense News. Archived from the original on 15 August 2024. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "US, UK take action targeting Russian aluminum, copper and nickel". Reuters. 12 April 2024.

- ^ "Nornickel moves production to China to circumvent sanctions". The Barents Observer. 24 April 2024. Archived from the original on 26 August 2024. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ "Exclusive: Nornickel in talks with China Copper to move smelting plant to China, sources say". Reuters. 9 July 2024.

- ^ "Nornickel weighs projects in new top market China". Mining Weekly. 19 July 2024.

- ^ "Biden's sanctions of Russian energy give electric vehicle batteries a pass". CNN. 10 March 2022. Archived from the original on 20 May 2024. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ Cheng, Evelyn (2 March 2022). "China will not join sanctions against Russia, banking regulator says". CNBC.

- ^ Aitken, Peter (2022-02-23). "Chinese media accidentally posts CCP rules on Russia-Ukraine coverage, hint at Taiwan takeover". Fox News. Archived from the original on 2022-02-23. Retrieved 2022-03-10.

- ^ "China's 2022 trade with Russia hit record $190 bln - customs". Reuters. 2023-01-13. Archived from the original on 2023-01-17. Retrieved 2023-01-18.

- ^ a b Prokopenko, Alexandra (2 February 2023). "The Risks of Russia's Growing Dependence on the Yuan". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- ^ "China Drives Russia Car Sales After Global Brands Quit Over War". Bloomberg News. 2023-07-06. Archived from the original on 2023-07-06. Retrieved 2023-07-07.

- ^ "China-Russia 2023 trade value hits record high of $240 bln - Chinese customs". Reuters. 12 January 2024.

- ^ "Nearly all Chinese banks are refusing to process payments from Russia, report says". Business Insider. 14 August 2024. Archived from the original on 25 August 2024. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ "Bank of China Halts Payments With Sanctioned Russian Lenders – Kommersant". The Moscow Times. 24 June 2024. Archived from the original on 13 August 2024. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ "China's trade with Russia is getting so difficult that payments can take half a year and most bank transfers are returned, report says". Business Insider. 30 July 2024. Archived from the original on 25 August 2024. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ "Analysts: China-Russia financial cooperation raises red flag". Business Insider. 30 July 2024. Archived from the original on 25 August 2024. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ Standish, Reid (24 July 2024). "China In Eurasia Briefing: How The Ukraine War Is Redrawing Global Trade Between Europe And China". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

- ^ a b "德语媒体:在中国被捧为英雄的普京". Deutsche Welle (in Simplified Chinese). Archived from the original on 2022-10-11. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ a b "从历史到现实 中港台三地民众如何观察俄乌之战". BBC News (in Simplified Chinese). Archived from the original on 2022-03-10. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ "Ukraine Invasion Sparks Controversial Commentary on Chinese Social Media". Voice of America. Archived from the original on 2022-03-04. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ 呼延朔 (2022-03-05). "俄烏戰爭「撕裂」中國民間輿論場". HK01 (in Traditional Chinese). Archived from the original on 2022-09-24. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ "中国社媒封杀反战声音 金星谴责普京被微博禁言 | DW | 02.03.2022". Deutsche Welle (in Simplified Chinese). Archived from the original on 2022-09-24. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ "反戰聲不息 衝不破牆壁 - 20220301 - 中國". Ming Pao (in Traditional Chinese). Archived from the original on 2022-03-01. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ "批蒲亭發動侵略戰爭 北京清華校友連署取消榮譽博士學位 | 兩岸 | 中央社 CNA". Central News Agency (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2022-03-06. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ "中国多位历史学家反战公开信遭封杀 海内外中国大学校友联署反战". Voice of America (in Simplified Chinese). Archived from the original on 2022-03-09. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ "【CDTV】TA们站了出来,公开表态"停止战争,支持乌克兰"". China Digital Times (in Simplified Chinese). 2022-02-27. Archived from the original on 2022-03-12. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ "【立此存照】不允许反战的国家:女艺人金星、柯蓝为乌克兰发声被禁言". China Digital Times (in Simplified Chinese). 2022-03-02. Archived from the original on 2022-03-21. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ "不允许反战的国家:女艺人金星、柯蓝为乌克兰发声被禁言". Radio Free Asia (in Simplified Chinese). Archived from the original on 2022-03-03. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ "乌克兰华人接到噩耗痛哭:好朋友为国牺牲,同学弟弟奔赴战场" [Ukrainian Chinese cried bitterly after receiving the bad news: good friends sacrificed for the country, classmates and younger brothers rushed to the battlefield]. NetEase. 2022-02-27. Archived from the original on 2022-07-09.

- ^ "西安生活7年的乌克兰留学生发声引热议:俄没资格为乌做决定" [A Ukrainian student who has lived in Xi'an for 7 years speaks out: Russia is not qualified to make decisions for Ukraine]. NetEase. 2022-02-27. Archived from the original on 2022-07-09.

- ^ 多维新闻 (2022-02-27). "中国网民称"收留乌克兰美女" 乌现反华情绪 华人安全受瞩|多维新闻|中国". Duowei News (in Simplified Chinese). Archived from the original on 2022-04-04. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ "烏媒指中國「支持俄入侵」 內地網民稱「收留烏美女」 烏現反華情緒 中使館籲公民勿亮身分". Ming Pao (in Traditional Chinese). Archived from the original on 2023-01-26. Retrieved 2023-01-26.

- ^ "戲謔戰爭掀反華情緒 中國留學生在烏克蘭被潑水 | 國際 | 中央社 CNA". Central News Agency (Taiwan) (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2022-03-07. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ "凤凰连线 | 乌克兰出现反华情绪 在乌华人呼吁不要调侃战争". Phoenix TV. Archived from the original on 2022-03-10. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ a b "兩岸「烏克蘭美女」言論惹議 專家:突顯長久問題" [Cross-strait "Ukrainian beauty" remarks provoke controversy Experts: Highlight long-standing problems]. Deutsche Welle (in Simplified Chinese). March 7, 2022. Archived from the original on 2022-04-21.

- ^ "媒体:呼吁对战争理性发言,切勿做隔岸观火的低俗看客_舆论场_澎湃新闻-The Paper". The Paper (in Chinese). Shanghai United Media Group. Archived from the original on 2022-02-27. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ "Sexist Ukraine comments spark China backlash". Deutsche Welle. March 8, 2022. Archived from the original on 2023-01-26. Retrieved 2024-02-04.

- ^ Ni, Vincent (2022-02-28). "'They were fooled by Putin': Chinese historians speak out against Russian invasion". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2022-03-21. Retrieved 2023-06-22.

- ^ "從歷史到現實 中港台三地民眾如何觀察俄烏之戰". BBC News (in Traditional Chinese). February 25, 2022. Archived from the original on 2022-03-10. Retrieved 2022-03-02.

- ^ "Possible Outcomes of the Russo-Ukrainian War and China's Choice". US-China Perception Monitor. March 12, 2022. Archived from the original on March 23, 2022. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ^ "Chinese opera singer sparks fury after performing in bombed Ukrainian theater". CNN. 2023-09-09. Archived from the original on 2023-09-09. Retrieved 2023-09-09.

- ^ "Chinese star sings Russian war ballad in Mariupol theatre ruins". The Times. 2023-09-09. Archived from the original on 2023-09-09. Retrieved 2023-09-09.

"The performance of the Chinese 'opera singer' Wang Fang of the song Katyusha in the ruins of the drama theatre in Mariupol, in which the Russian army killed more than 600 innocent people, is an example of complete moral degradation", said Oleg Nikolenko, a spokesman for Ukraine's foreign ministry, on Facebook. Nikolenko said the Chinese delegation's visit to occupied Ukraine was illegal and demanded an explanation from Beijing.

- ^ "Chinese bloggers arrive in Mariupol: Foreign Ministry wants to ban all "touring" Chinese bloggers from Ukraine". Ukrainska Pravda. 2023-09-08. Archived from the original on 2023-09-08. Retrieved 2023-09-09.

- ^ "МЗС України ініціює заборону в'їзду до країни для всіх китайських гастролерів". imi.org.ua (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 2024-02-25. Retrieved 2024-02-25.

- ^ Hernández, Javier C. (2023-09-10). "Chinese Singer Denounced Over Video at Bombed-Out Ukrainian Theater". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2023-09-11. Retrieved 2024-02-25.

- ^ "Countries united in sympathy for Ukraine even as sanctions generate mixed reactions: Blackbox poll across Australia, China, India, and Singapore". Blackbox. 28 March 2022. Archived from the original on 13 October 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ Laura Zhou (20 April 2022). "Ukraine war: most Chinese believe backing Russia is in their national interest, says US think tank". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 25 September 2022. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ "How do the Chinese view the Taiwan Strait issue and the Russian invasion of Ukraine?". Genron NPO. November 30, 2022. Archived from the original on January 26, 2023.

- ^ Nobuyoshi, Sakajiri (December 22, 2022). "INTERVIEW/ NPO head details rare survey of Chinese views on Ukraine, Taiwan". The Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on December 22, 2022.

- ^ Scott Moskowitz (2023-02-23). "Chinese Views on the War in Ukraine and Lethal Aid at the One-Year Mark". Morning Consult. Archived from the original on 2023-09-22.

- ^ Pancevski, Bojan; Mackrael, Kim (2023-05-26). "Europe Rebuffs China's Efforts to Split the West in Pushing Ukraine Cease-Fire". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 2023-06-04. Retrieved 2023-05-27.

- ^ Hanke Vela, Jakob (2024-02-13). "EU proposes sanctions on Chinese firms for helping Russia". Politico Europe. Archived from the original on 2024-02-21. Retrieved 2024-02-28.

- ^ Bermingham, Finbarr (2024-11-13). "EU's next top envoy says China must pay 'higher cost' for supporting Russia". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 2024-11-13.

- ^ Bermingham, Finbarr (2024-11-15). "EU has 'conclusive' proof of Chinese armed drones meant for Russia: sources". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 2024-11-16.

- ^ "NATO Accuses China Of Backing Russia With "Blatant Lies"". NDTV. 23 March 2022. Archived from the original on 21 March 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- ^ "NATO chief reiterates Ukraine's right to strike 'legitimate military targets' inside Russia". Anadolu Agency. 31 May 2024. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ a b "US, NATO urge China to 'stop' beefing Russia's defence amid Ukraine war". TRT World. 18 June 2024. Archived from the original on 19 June 2024. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ Michaels, Daniel (6 July 2024). "China's Support for Russia's War in Ukraine Puts Beijing on NATO's Threat List". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 7 July 2024. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ "NATO slams China over Russia support, backs full integration of Ukraine, draft communique says". Reuters. July 10, 2024. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ Buli, Nora (September 6, 2024). "NATO chief urges China to stop supporting Russia's war in Ukraine". Reuters. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ Anderlini, Jamil; Vinocur, Nicholas (2023-07-19). "China 'complicit' in Russia's invasion of Ukraine, MI6 chief tells POLITICO". Politico Europe. Archived from the original on 2023-07-19. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ^ a b Harding, Luke; Walker, Shaun (2024-05-23). "US challenges British claim China is sending 'lethal aid' to Russia". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-07-20.

- ^ "US's Blinken raises China's 'alignment with Russia' on Ukraine". Al Jazeera. 9 July 2022. Archived from the original on 20 March 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- ^ Nardelli, Alberto; Jacobs, Jennifer (April 6, 2024). "China Is Providing Geospatial Intelligence to Russia, US Warns". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on April 6, 2024. Retrieved April 6, 2024.

- ^ "Zelensky: Ukraine is fine with China's position on war with Russia". Archived from the original on 2022-05-28. Retrieved 2022-05-30.

China has chosen the policy of staying away. At the moment, Ukraine is satisfied with this policy. It is better than helping the Russian Federation in any case. And I want to believe that China will not pursue another policy. We are satisfied with this status quo, to be honest.

- ^ Hatton, Celia (26 April 2023). "Ukraine's Zelensky holds first war phone call with China's Xi". BBC News. Archived from the original on 14 February 2024. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "Zelenskyy urges China's Xi to help end Russia's war in Ukraine". Al Jazeera. 4 August 2022. Archived from the original on 22 October 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- ^ "Poll: 94% of Ukrainians have negative view of Russia, Belarus ranks second worst". The Kyiv Independent. 5 April 2023. Archived from the original on 10 August 2023. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ^ "Survey: the majority of Ukrainians have a positive attitude towards Georgia". The Odessa Journal. 4 March 2024. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 25 May 2024.

Respondents most frequently expressed positive attitudes towards Lithuania (91%), Latvia (90.5%), the United Kingdom (90%), Germany (89%), Estonia (89%), Canada (88%), the United States (87%), France (86%), the Czech Republic (86%), Poland (86%), the Netherlands (83%), Moldova (81%), Japan (74%), Georgia (72%), Israel (65%)...Negative attitudes were most commonly expressed towards Russia (95% of respondents had a negative attitude), Belarus (87%), Iran (82%), China (72.5%), and Hungary (59%).

- ^ "Attitude to foreign countries, international organisations and politicians, and Ukraine's accession to the European Union (January, 2024)". Razumkov Centre. February 28, 2024. Archived from the original on July 16, 2024. Retrieved May 25, 2024.

- ^ "Zelensky says China's 'support to Russia' will extend war in Ukraine during surprise appearance in Asia". CNN. 3 June 2024. Archived from the original on 19 June 2024. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ "Brussels plans sanctions on Chinese companies aiding Russia's war machine". Financial Times. 2023-05-07. Archived from the original on 2023-05-07. Retrieved 2023-05-08.

- ^ Bermingham, Finbarr (2023-06-15). "EU cuts 5 Chinese firms from sanctions list after Beijing vows to stop flow of military goods to Russia". Archived from the original on 2023-06-21. Retrieved 2023-06-21.

- ^ "EU Eyes Export Ban on Three Chinese Firms". Voice of America. Agence France-Presse. 2024-02-13. Archived from the original on 2024-02-14. Retrieved 2024-02-14.

- ^ "China Defends Stance on Russia After U.S. Criticism". Agence France-Presse. 2022-04-14. Archived from the original on 2022-09-28. Retrieved 2022-06-05.

- ^ Alper, Alexandra (2022-06-29). "U.S. accuses five firms in China of supporting Russia's military". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2023-03-22. Retrieved 2022-07-01.

- ^ "US blacklists 25 Chinese entities, including firms aiding Russia's military". South China Morning Post. 2022-06-30. Archived from the original on 2022-06-30. Retrieved 2022-07-01.

- ^ a b "Treasury Imposes Swift and Severe Costs on Russia for Putin's Purported Annexation of Regions of Ukraine". U.S. Department of the Treasury. September 30, 2022. Archived from the original on 2023-03-12. Retrieved 2022-09-30.

- ^ Talley, Ian; DeBarros, Anthony (2023-02-04). "China Aids Russia's War in Ukraine, Trade Data Shows". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 2023-03-12. Retrieved 2023-06-21.

- ^ Pao, Jeff (2022-06-30). "US starts sanctioning China for supporting Russia". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 2022-09-30. Retrieved 2022-09-30.

- ^ Marlow, Iain; Flatley, Daniel (January 26, 2023). "US Targets Chinese Company in Broader Russia Sanctions Push". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on December 20, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2023.

- ^ "US joins EU in rejecting Beijing's peace plan, sanctions more Chinese firms". South China Morning Post. 2023-02-25. Archived from the original on 2023-02-25. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ^ Freifeld, Karen; Heavey, Susan; Alper, Alexandra (2023-02-24). "U.S. hits Chinese, Russian firms for aiding Russian military". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2023-02-24. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ^ Psaledakis, Daphne; Mohammed, Arshad (2023-04-12). "U.S. sanctions hit over 120 targets supporting Russia's invasion of Ukraine". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2023-04-12. Retrieved 2023-04-12.

- ^ Wang, Orange (2023-03-10). "US sanctions 5 China-based suppliers to Iranian firm selling drones to Russia". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 2023-03-11. Retrieved 2023-03-10.

- ^ "US sanctions Chinese companies for supplying parts used in Iranian drones". Financial Times. 2023-03-09. Archived from the original on 2023-03-22. Retrieved 2023-03-10.

- ^ Singh, Kanishka; Martina, Michael; Singh, Kanishka (2023-07-27). "US intelligence report says China likely supplying tech for Russian military". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2023-07-27. Retrieved 2023-07-28.

- ^ Willemyns, Alex (July 27, 2023). "US intelligence: Beijing has increased Russia support". Radio Free Asia. Archived from the original on July 29, 2023. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- ^ "US restricts trade with 42 Chinese entities over Russia military support". Reuters. 2023-10-06. Archived from the original on 2023-10-06. Retrieved 2023-10-07.

- ^ Chiacu, Doina; Freifeld, Karen (April 10, 2024). "US restricts trade with companies tied to drones used by Russia, Houthis". Reuters. Retrieved April 10, 2024.

- ^ "US issues sanctions targeting Russia, takes aim at Chinese companies". Voice of America. Reuters. 2024-05-01. Archived from the original on 2024-07-26. Retrieved 2024-05-02.

- ^ Tang, Didi (2024-10-17). "US imposes sanctions on Chinese companies accused of helping make Russian attack drones". Associated Press. Retrieved 2024-10-17.

- ^ "China's growing role in Russia's war". The Economist. 22 February 2023. Archived from the original on 23 February 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ Leonard, Mark (7 August 2023). "What China really thinks about Ukraine". Politico. Archived from the original on 20 August 2023. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ Torigian, Joseph. "China's balancing act on Russian invasion of Ukraine explained". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 2022-03-19. Retrieved 2022-03-25.

- ^ "How close are China and Russia and where does Beijing stand on Ukraine?". The Guardian. March 16, 2022. Archived from the original on March 22, 2022. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ^ Duchesne, Érick. "Why China could become a mediator in negotiations between Russia and Ukraine". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 2022-03-19. Retrieved 2022-03-25.

- ^ Leoni, Zeno. "Ukraine conflict: the pros and cons of China as global peace mediator". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 2022-03-19. Retrieved 2022-03-25.