Adrafinil

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Olmifon |

| Other names | CRL-40028; N-Hydroxymodafinil |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 80% |

| Metabolism | 75% (liver) |

| Metabolites | Modafinil |

| Elimination half-life | 1 hour (T1/2 is 12–15 hours for modafinil)[5] |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.058.440 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

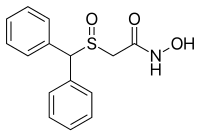

| Formula | C15H15NO3S |

| Molar mass | 289.35 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Adrafinil, sold under the brand name Olmifon, is a wakefulness-promoting medication that was formerly used in France to improve alertness, attention, wakefulness, and mood, particularly in the elderly.[6][7][8] It was also used off-label by individuals who wished to avoid fatigue, such as night workers or others who needed to stay awake and alert for long periods of time. Additionally, the medication has been used non-medically as a novel vigilance-promoting agent.[6]

Adrafinil is a prodrug; it is primarily metabolized in vivo to modafinil, resulting in very similar pharmacological effects.[6] Unlike modafinil, however, it takes time for the metabolite to accumulate to active levels in the bloodstream. Effects usually are apparent within 45–60 minutes when taken orally on an empty stomach.[citation needed]

Adrafinil was marketed in France until September 2011 when it was voluntarily discontinued due to an unfavorable risk–benefit ratio.[7]

Medical uses

[edit]Adrafinil is a wakefulness-promoting agent and was used to promote alertness, attention, wakefulness, and mood.[6] It was particularly used in the elderly.[6]

Available forms

[edit]Adrafinil was available in the form of 300 mg oral tablets.[9][7]

Side effects

[edit]There is a case report of two patients that adrafinil may increase interest in sex.[6]

A case report of adrafinil-induced orofacial dyskinesia exists.[10][11] Reports of this side effect also exist for modafinil.[10]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]Because α1-adrenergic receptor antagonists were found to block effects of adrafinil and modafinil in animals, "most investigators assume[d] that adrafinil and modafinil both serve as α1-adrenergic receptor agonists."[6] However, adrafinil and modafinil have not been found to bind to the α1-adrenergic receptor and they lack peripheral sympathomimetic side effects associated with activation of this receptor;[12] hence, the evidence in support of this hypothesis is weak, and other mechanisms are probable.[6] Modafinil was subsequently screened at a variety of targets in 2009 and was found to act as a weak, atypical blocker of the dopamine transporter (and hence as a dopamine reuptake inhibitor), and this action may explain some or all of its pharmacological effects.[13][14][15] Relative to adrafinil, modafinil possesses greater specificity in its action, lacking or having a reduced incidence of many of the common side effects of the former (including stomach pain, skin irritation, anxiety, and elevated liver enzymes with prolonged use).[16][17]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]In addition to modafinil, adrafinil also produces modafinil acid (CRL-40467) and modafinil sulfone (CRL-41056) as metabolites, which form from metabolic modification of modafinil.

Chemistry

[edit]Adrafinil is the N-hydroxylated analogue of modafinil and is also known as N-hydroxymodafinil.

Analogues of adrafinil include modafinil, armodafinil, CRL-40,940, CRL-40,941, and fluorenol, among others.

History

[edit]Adrafinil was discovered in 1974 by two chemists working for the French pharmaceutical company Laboratoires Lafon who were screening compounds in search of analgesics.[18] Pharmacological studies of adrafinil instead revealed psychostimulant-like effects such as hyperactivity and wakefulness in animals.[18] The substance was first tested in humans, specifically for the treatment of narcolepsy, in 1977–1978.[18] Introduced by Lafon (now Cephalon), it reached the market in France in 1984,[7] and for the treatment of narcolepsy in 1985.[18][19]

In 1976, two years after the discovery of adrafinil, its active metabolite modafinil was discovered.[18] Modafinil appeared to be more potent than adrafinil in animal studies, and was selected for further clinical development, with both adrafinil and modafinil eventually reaching the market.[18] Modafinil was first approved in France in 1994, and then in the United States in 1998.[19] Lafon was acquired by Cephalon in 2001.[20] As of September 2011, Cephalon has discontinued Olmifon, its adrafinil product, while modafinil continues to be marketed.[7]

Society and culture

[edit]Names

[edit]Adrafinil is the generic name of the drug and its INN and DCF.[8] It is also known by its brand name Olmifon and its developmental code name CRL-40028.[8]

Regulation

[edit]Athletic doping

[edit]Adrafinil and its active metabolite modafinil were added to the list of substances prohibited for athletic competition according to World Anti-Doping Agency in 2004.[21]

Additive in United States dietary supplements

[edit]Adrafinil is sometimes included as an ingredient in misbranded or adulterated dietary supplements. One company had attempted to get a New Dietary Ingredient pre-market notification approved for adrafinil in 2017, but the Food and Drug Administration rejected[22] it:

“For the reasons discussed above, the information in [this pre-market] notification is incomplete and does not provide an adequate basis to conclude that ‘Adrafinil’...will reasonably be expected to be safe. Therefore, [such] product may be adulterated under 21 U.S.C. § 342(f)(1)(B)...Introduction of such a product into interstate commerce is prohibited under 21U.S.C.§331(a) and (v)”.

A position that adrafinil is an unapproved drug was indicated in a warning letter[1] by the FDA in 2019:

“Your [particular] products [subject to this warning] [including] Adrafinil…are not generally recognized as safe and effective for the above referenced uses and, therefore, these products are 'new drugs' under section 201(p) of the Act. New drugs may not be legally introduced or delivered for introduction into interstate commerce without prior approval from the FDA...”

A position that adrafinil is an unapproved drug was also indicated by FDA in a press release regarding a criminal action[2] undertaken in 2019:

“[Defendant in the 2019 enforcement action] falsely represented these drugs as legal to sell in the United States. In fact, these are drugs that were illegally imported into the United States and illegal to sell in the United States because they are not approved for sale by the Food and Drug Administration... Some of the illegal drugs [defendant] was selling include the following...Adrafinil...”

FDA indicated a position that adrafinil is an unapproved drug in later criminal action undertaken during 2022: “[The defendants in a 2022 enforcement action] also illegally sold multiple other unapproved and misbranded drugs, including adrafinil crystalline powder...” [3] Most recently in 2023, the FDA fined[4] an Arizona company 2.4 million U.S. dollars for introducing misbranded drugs into interstate commerce:

Between April 2017 and December 2021, [defendant company in 2023 enforcement action] and [its executive] marketed pharmaceutical drugs, including tianeptine, adrafinil, phenibut, and racetams, on [its website] and online platforms...They sold the drugs to customers across the United States. [Company] employees and [the company's executive] also regularly made representations about the company’s drugs through a [online] forum dedicated to [defendant company's products] products. As part of the plea, [the defendant] has agreed to forfeit $2.4 million. [The defendant] has also agreed to forfeit all tianeptine, adrafinil, phenibut, and racetams seized by the FDA and Customs and Border Protection. FDA has not approved drugs containing tianeptine, adrafinil, phenibut, and racetams for use in the United States. Racetam drugs include piracetam, aniracetam, and coluracetam, and phenylpiracetam."

Certain products, formulated with adrafinil in them, have been listed as subject to a May 2023 import alert by Food and Drug Administration because they are considered as containing an active pharmaceutical ingredient.[23]

Adrafinil containing products, purporting to be dietary supplements, are not allowed for use by military service members. This is because the Department of Defense considers adrafinil an unapproved drug.[24]

New Zealand

[edit]In 2005 a Medical Classification Committee in New Zealand recommended to MEDSAFE NZ that adrafinil be classified as a prescription medicine due to risks of it being used as a party drug. At that time adrafinil was not scheduled in New Zealand.[25]

Research

[edit]In a clinical trial with the tricyclic antidepressant clomipramine and placebo as comparators, adrafinil showed efficacy in the treatment of depression.[6] In contrast to clomipramine however, adrafinil was well-tolerated, and showed greater improvement in psychomotor retardation in comparison.[6] The authors concluded that further investigation of the potential antidepressant effects of adrafinil were warranted.[6]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Peak Nootropics LLC aka Advanced Nootropics - 557887 - 02/05/2019". Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2019-12-20. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ a b Office of Regulatory Affairs (2019-12-20). "Hermitage Man Sentenced for Importing and Selling Drugs Not Approved by FDA". U.S. Department of Justice – via U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

- ^ a b "Fort Collins Couple Sentenced to Federal Prison for Illegally Selling Unapproved Drugs". Food and Drug Administration. FDA Office of Criminal Investigations. June 10, 2022. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ a b "Arizona Company and CEO Plead Guilty to the Distribution of Drugs Not Approved by the FDA and Will Pay $2.4 Million". Food and Drug Administration. FDA Office of Criminal Investigations. October 30, 2023. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ^ Robertson P, Hellriegel ET (2003). "Clinical pharmacokinetic profile of modafinil". Clin Pharmacokinet. 42 (2): 123–37. doi:10.2165/00003088-200342020-00002. PMID 12537513. S2CID 1266677.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Milgram N (1999). "Adrafinil: A Novel Vigilance Promoting Agent". CNS Drug Reviews. 5 (3): 193–212. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.1999.tb00100.x.

- ^ a b c d e AFSSAPS (2011). "Point d'information sur les dossiers discutés en commission d'AMM Séance du jeudi 1er décembre 2011 - Communiqué". Archived from the original on 13 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. January 2000. pp. 20–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ^ Kleemann A, Engel J, Kutscher B, Reichert D, Kleemann A, Engel J, et al. (2009). Pharmaceutical Substances (5th: Syntheses, Patents and Applications of the most relevant APIs ed.). Georg Thieme Verlag. ISBN 978-3-13-179525-0.

- ^ a b Aronson JK (31 December 2012). Side Effects of Drugs Annual: A worldwide yearly survey of new data in adverse drug reactions. Newnes. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-0-444-59503-4.

- ^ Thobois S, Xie J, Mollion H, Benatru I, Broussolle E (2004). "Adrafinil-induced orofacial dyskinesia". Mov. Disord. 19 (8): 965–6. doi:10.1002/mds.20154. PMID 15300665. S2CID 31816404.

- ^ Simon P, Chermat R, Puech AJ (1983). "Pharmacological evidence of the stimulation of central alpha-adrenergic receptors". Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 7 (2–3): 183–6. doi:10.1016/0278-5846(83)90105-7. PMID 6310690. S2CID 45147850.

- ^ Zolkowska D, Jain R, Rothman RB, Partilla JS, Roth BL, Setola V, Prisinzano TE, Baumann MH (May 2009). "Evidence for the involvement of dopamine transporters in behavioral stimulant effects of modafinil". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 329 (2): 738–46. doi:10.1124/jpet.108.146142. PMC 2672878. PMID 19197004.

- ^ Reith ME, Blough BE, Hong WC, Jones KT, Schmitt KC, Baumann MH, Partilla JS, Rothman RB, Katz JL (Feb 2015). "Behavioral, biological, and chemical perspectives on atypical agents targeting the dopamine transporter". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 147: 1–19. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.005. PMC 4297708. PMID 25548026.

- ^ Quisenberry AJ, Baker LE (Dec 2015). "Dopaminergic mediation of the discriminative stimulus functions of modafinil in rats". Psychopharmacology. 232 (24): 4411–9. doi:10.1007/s00213-015-4065-0. PMID 26374456. S2CID 15519396.

- ^ Ballas CA, Kim D, Baldassano CF, Hoeh N (July 2002). "Modafinil: past, present and future". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2 (4): 449–457. doi:10.1586/14737175.2.4.449. PMID 19810941. S2CID 32939239.

- ^ Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB (2009). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychopharmacology. American Psychiatric Pub. pp. 850–. ISBN 978-1-58562-309-9.

- ^ a b c d e f Guglietta A (28 November 2014). Drug Treatment of Sleep Disorders. Springer. pp. 212–. ISBN 978-3-319-11514-6.

- ^ a b Li JJ, Johnson DS (27 March 2013). Modern Drug Synthesis. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 2–. ISBN 978-1-118-70124-9.

- ^ "Stocks". Bloomberg.com. 2023-05-24. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

- ^ "Prohibited List" (PDF). World Anti-Doping Agency. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-04-10.

- ^ "Regulations.gov". www.regulations.gov. Retrieved 2023-05-20.

- ^ "Import Alert 54-16". www.accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved 2023-05-22.

- ^ "DOD PROHIBITED DIETARY SUPPLEMENT INGREDIENTS". Operation Supplement Safety. Retrieved 2023-05-31.

- ^ "MCC Minutes Out of Session Meeting". Medsafe.govt.nz. 23 May 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

Further reading

[edit]- Milgram NW, Callahan H, Siwak C (September 1992). "Adrafinil: A Novel Vigilance Promoting Agent". CNS Drug Reviews. 5 (3): 193–212. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.1999.tb00100.x.

- Thobois S, Xie J, Mollion H, Benatru I, Broussolle E (August 2004). "Adrafinil-induced orofacial dyskinesia". Movement Disorders. 19 (8): 965–966. doi:10.1002/mds.20154. PMID 15300665. S2CID 31816404.

External links

[edit]- "Adrafinil". PubChem Substance Summary. National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. CID 3033226. Retrieved 7 December 2005.

- "Adrafinil - Bank of Automated Data on Drugs". Bank of Automated Data on Drugs. VIDAL. Archived from the original on 5 October 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2008.