International Gothic art in Italy

International Gothic (or Late Gothic) art is a style of figurative art datable between about 1370 and, in Italy, the first half of the 15th century.

As the name emphasizes, this stylistic phase had an international scope, with common features as well as many local variables. The style did not spread from a center of irradiation, as had been the case, for example, with Gothic art and the Île-de-France, but was rather the result of a dialogue between European courts, fostered by the numerous mutual exchanges.[1] Among these courts, the papal court played a prominent role, particularly the Avignon court, a true center of gathering and exchange for artists from all over the continent.[2]

Italy, politically divided, was traversed by artists who spread this style, moving constantly (especially Pisanello, Michelino da Besozzo and Gentile da Fabriano) and also generating numerous regional variations. The "international" Gothic style meant the rejuvenation of the Gothic tradition (still linked at the end of the 14th century to the style of Giotto), but only some areas offered original and "leading" contributions to the European scene, while others only partially and more superficially acquired individual stylistic features. Prominent among the areas were Lombardy and, to varying degrees, Venice and Verona. In Florence International Gothic art came into early competition with the nascent Renaissance style, but it nevertheless met with favor among the rich and cultured clientele, both religious and private.[3]

Lombardy

[edit]

Under Gian Galeazzo Visconti (in power from 1374 to 1402) a political program was begun aimed at unifying northern Italy into a monarchy. In 1386 the construction of Milan Cathedral began, for which Visconti called in French and German workers,[3] while in 1396 the same lord laid the foundation stone of the Certosa di Pavia.

Visconti's atelier of miniaturists was mainly active in Pavia (in whose castle Gian Galeazzo's court was based) and by about 1370 had already elaborated a refined fusion of Giottesque chromaticism and courtly and chivalric themes. Protagonists of this early period were the anonymous miniaturist author of the Guiron le Coutois and the Lancelot du Lac, now in the National Library of France in Paris, and Giovannino de' Grassi, who illuminated the prayer book known as the Hours of Gian Galeazzo Visconti, with representations of great linear elegance, naturalistic accuracy and decorative preciousness.[4] The next generation, especially in the personality of Michelino da Besozzo, elaborated this legacy even more freely, imaginatively and internationally. In the Offiziolo Bodmer he used a flowing line, soft colors and a precious rhythm in the drawing of figures, which indifferently disregarded spatial issues; all were enriched by very fresh naturalistic details, taken from direct observation.[3]

Michelino's graceful style was successful and widely followed for a long time. For example, still in 1444, the frescoes in the Chapel of Teodolinda in the Cathedral of Monza by the Zavattari brothers are characterized by muted hues, astonished and weightless characters taken from the courtly world; other examples can also be counted for the second half of the 15th century.[5]

The other strand alongside Michelino's gentle style was the grotesque style, evidenced by the works of Franco and Filippolo de Veris in the fresco of the Last Judgment in the church of Santa Maria dei Ghirli in Campione d'Italia (1400), or the expressive miniatures of Belbello da Pavia. For example, in the Bible of Niccolò d'Este, illuminated by Belbello in 1431-1434, fluid, deforming lines, physically imposing figures, excessive gestures, and bright, iridescent colors are used. He remained faithful to this lexicon throughout his long career, until about 1470.[5]

In the secular field, the major pictorial cycles preserved today, with elegant scenes illustrating the pastimes of courtly life, are the fresco cycle of the so-called Borromeo Games in the Borromeo Palace in Milan, the decorations of the Sala degli Svaghi and the Sala dei Vizi e delle Virtù in the Masnago Castle, whose authors have not yet been identified[6] and the dames commissioned by Gian Galeazzo in 1393 to be frescoed in the "ladies' room" of the Visconti Castle, recently attributed to Gentile da Fabriano.[7]

-

Apsidal part of the Milan Cathedral

-

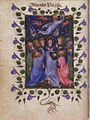

Michelino da Besozzo, Offiziolo Bodmer (Book of Hours), first half of the 15th century, Pierpont Morgan Library, New York

-

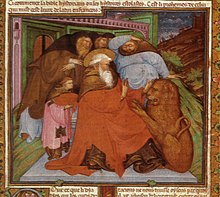

Franco and Filippolo de Veris, Last Judgment, Santa Maria dei Ghirli, Campione d'Italia (1400).

-

Detail of Bernando Visconti.

-

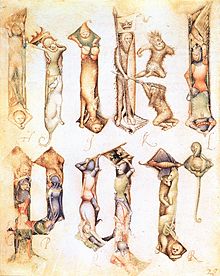

Visconti-era miniature.

-

The interior of the Certosa di Pavia

Venice

[edit]

In the first two decades of the 15th century Venice initiated a momentous political shift, concentrating its interests toward the mainland, inserting itself more actively into the Western framework and gradually detaching itself from Byzantine influence. In painting, sculpture and architecture there was a contemporary grafting of late Gothic motifs, amalgamated with the Byzantine substratum: the linear and chromatic finesse of Gothic art were in fact very akin to the sumptuous abstractions of the oriental stamp. The renovation was also favored by the influx of artists from outside, enlisted at St. Mark's Basilica and the Doge's Palace.[8]

The Basilica was crowned with domes, and it was decided in 1422 to extend the Doge's Palace on the side of the square to St. Mark's, continuing the style of the earlier, 14th-century part. Thus was consecrated a "Venetian" architectural style, free from the European trends of the time, which was reused for centuries. Belonging to this style are the elegant poliforas with finely ornamented arches of Ca' Foscari, Palazzo Giustinian and Ca' d'Oro, where at one time the facade was also decorated with dazzling gilding and polychrome effects. These palaces are characterized by a ground-floor portico open to the water for docking vessels, while the upper floor is lit by large poliforas, usually at the central hall, which is reached by a grand staircase that also serves the other rooms. The small arches create dense and modular decorations, which multiply the openings and create rhythms of lace-like chiaroscuro.[9]

The Doge's Palace was covered with frescoes between 1409 and 1414, featuring renowned artists such as Pisanello, Michelino da Besozzo and Gentile da Fabriano, works now almost totally lost due to various causes. The Venetian influence is seen in some of Gentile's works, such as the Coronation of the Virgin in the Valle Romita Polyptych (1400-1410), painted for a hermitage near Fabriano.[8]

-

Doge's Palace (completed by 1422).

-

Palazzo Giustinian and Ca' Foscari (15th century).

-

Palazzo Bernardo (first half of the 15th century).

-

Gothic architecture in Koper.

Istria

[edit]In Istria, Venetian territory, John of Kastav worked in the Holy Trinity Church in Hrastovlje, and Vincenzo di Càstua[10] in the sanctuary of Santa Maria alle Lastre in Beram.

Verona

[edit]

Verona, although subjugated to Venice from 1406, long maintained its own artistic school, closer to the Lombard style brought by the earlier Visconti domination and the stay of artists such as Michelino da Besozzo (Madonna of the Rose Garden, c. 1435).[11]

Prominent was the painter Stefano da Verona, son of a French painter (Jean d'Arbois, who was formerly in the service of Philip II of Burgundy and Gian Galeazzo Visconti). In the Adoration of the Magi (signed and dated 1435), he constructed with soft strokes and sinuous lines one of the finest works of international Gothic art, paying great attention to detail, to the rendering of precious materials and fabrics, and to the calibration of the crowded composition, with a mostly linear style.[11]

However, the most important artist active in Verona was Pisanello, who brought northern figurative art to its peak. In the Pellegrini Chapel of the church of Santa Anastasia is located his best-known work, Saint George and the Princess, wherein a wholly personal manner he mixed elegance of detail and tension of narrative, reaching heights of "idealized realism." Today the paintings are not in the best state of preservation, with many alterations to the paint surface and the loss of the entire left side. Pisanello later moved to other Italian courts (Pavia, Ferrara, Mantua, Rome), where he spread his artistic accomplishments, being in turn influenced by local schools, with particular regard to the rediscovery of the ancient world already promoted by Petrarch, to which he devoted himself by copying numerous Roman reliefs into drawings that have partly come down to us. Also extraordinary is his production of drawings, and veritable studies from life, among the first in the history of art to acquire a value independently of the finished panel work.[12]

Trentino Alto Adige

[edit]

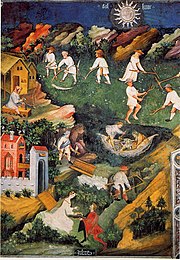

Trentino was linked beyond the Alpine range to German-speaking and Central European countries. The entire area is rich in secular cycles, among which the work of Master Wenceslas, of Bohemian origin, who decorated the Eagle Tower in the Buonconsiglio Castle in Trent with the Cycle of the Months, commissioned by George of Lichtenstein, stands out for its richness and quality. The scenes are rich in details inferred from the iconographies of the Tacuina sanitatis, with a dense interweaving of the chivalrous and everyday worlds, yet devoid of grotesque overtones.[13]

Another interesting piece of evidence, in the Alpine area, is Sibyl's fresco, found in Cortina d'Ampezzo. The fresco has survived in fragments: the scene probably compared six or more Sibyls in pairs, holding scrolls. Five remain: from the left, one recognizes the "Sibyl Valuensis," a symbol of justice. The second, holding a palm tree, may be the "Sibyl Nicaulia" or "Tiburtina." The central sibyl with three lions, according to the scroll she is holding, is the "Sibilla Portuensis"; but it could also be the "Sibilla Libica," because of the presence of the lions. The fourth, best preserved one should be the "Erythraean Sibyl," pointing to the rays of the Sun with her right hand. The fifth sibyl wears a different crown and looks outward.

Johannes Hinderbach, Bishop of Trent, enlarged his residence, the Buonconsiglio Castle in Trent, by making, among other things, a Venetian loggia with Corinthian capitals in Gothic style in the 15th century.[14]

In South Tyrol, the frescoes with chivalric and profane-courtly cycles in Runkelstein Castle and Rodengo Castle are relevant and valuable, while in Trentino those in Castle of Avio are worth mentioning.

Savoy, Piedmont and Aosta Valley

[edit]

The entire Alpine range had always been traversed via the passes by various flows of travelers, which is why it was a place of smooth cultural exchanges.

In Piedmont, Amadeus VIII linked his duchy through close diplomatic relations to Berry and Burgundy, going so far as to marry Mary of Burgundy, the daughter of the Duke of Burgundy Philip the Bold. The art produced at his court reflected this cosmopolitan climate, with artists such as Giacomo Jaquerio.[13]

He took Burgundian sculpture as his model, but soon developed a more personal style, where the finest stylistic sweetnesses and the sharpest expressive depictions coexisted, as in the moving Ascent to Calvary frescoed in the former sacristy of the church of St. Anthony in Ranverso (c. 1430). In the great variety of human types in the procession around Christ, a linear sense prevails due to the pronounced black line of the borders, yet each subject detaches expressively from the neutral background and group, creating a dramatic vision devoid of sentimentality.[13]

The Master of the Castello della Manta, formerly identified as Jaquerio and now regarded as a separate individual,[15] painted around 1420 a cycle of fine frescoes in the castle near Saluzzo, very rich in courtly elements on a bright, yet flat, white background. In scenes such as the Fountain of Youth, the fairy-tale world of sinuous lines, drawn from private miniatures, is transferred to a monumental scale, with great attention to detail and numerous genre scenes: the heavy trudging of the elderly, men undressing, the old woman acting as a stepladder to her sore peer, the scenes of love and joy within the elaborate Gothic miraculous fountain.[16]

In the Aosta Valley, the frescoes in Fénis Castle and Issogne Castle belong to the International Gothic.

Marche and Umbria

[edit]

In the Marches there was a period of sudden artistic flourishing due to the emergence of special wide-ranging political and commercial relations. Small local lordships undertook very active exchanges with the Emilian, Venetian and Lombard area, as during the lordship of Pandolfo II Malatesta, lord of Fano, but also of Bergamo and Brescia, or during the alliance of many small local lords with Gian Galeazzo Visconti in an anti-Florentine perspective.[17]

Ancona, at once antagonist and admirer of the Serenissima, from the mid-15th century began an ambitious restyling of its monuments according to the latest trends of the time, following the Venetian style. The architect Giorgio di Matteo, first called to the city by the Benincasa family of shipowners, who commissioned him to build the new family palace, was the architect behind this turnaround. Later the Council of the Republic entrusted him sequentially with the constructions of the Loggia dei Mercanti in 1451, the Church of San Francesco alle Scale, where in 1454 he made the portal, one of his highest masterpieces, and the Church of Sant'Agostino, where in 1460 he made another remarkable portal.

In San Severino Marche the Smeducci family had a period of considerable economic prosperity with trade beyond the region. This economic and cultural openness is reflected in works such as Lorenzo Salimbeni's Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine (1400, Pinacoteca comunale di San Severino), characterized by a swirling movement of the lines of the drapery, unreal colors and detailed realism, following the most up-to-date Lombard-Emilian and French models.[17] A masterpiece of the Salimbeni brothers, in an excellent state of preservation, are the frescoes in the oratory of St. John the Baptist in Urbino.

In San Ginesio there is tangible evidence of foreign contributions in the field of architecture with an ornate terracotta decoration applied to the old facade of the Collegiate Church of Santa Maria Assunta in 1421 by a certain master Enrico Alemanno, a Bavarian,[18] brother of Pietro Alemanno, thus making it the only example of late Gothic, precisely florid Gothic, in the Marche region.[19]

Gentile da Fabriano, a native of the Marche town near Umbria, was one of the greatest exponents of the Late Gothic style throughout the peninsula. Nourished by an Umbrian-Marche background with Lombard influences, taken on as a result of frequent travels, he fostered the flourishing of the Late Gothic style at first not far from his hinterland (the frescoes of humanistic inspiration inside the Palazzo Trinci in Foligno are illustrative), later gaining prominence even farther afield: to this day in Florence, the Adoration of the Magi, his greatest work, is on display in the Uffizi Gallery. In Umbria, the Late Gothic style also flourished due to the Salimbeni brothers. Ottaviano Nelli, who worked throughout the region, was formed in Gubbio

Active in Terni were Francesco di Antonio, more commonly called Maestro della Dormitio di Terni, and Bartolomeo di Tommaso.

Florence

[edit]

In Florence the International Gothic penetrated with very specific characteristics (as had happened with Gothic painting), linked strongly, as a tradition, to classicism. The city at the beginning of the 15th century was beginning a period of apparent stability, after the serious upheavals of the previous century, with the end of the Visconti threat, territorial (subjugation of Pisa in 1406, of Cortona in 1411, of Livorno in 1421) and economic growth dominated by the bourgeoisie. The costs of these achievements, however, wore down the political class from within, paving the way for the advent of the oligarchy, which came to fruition in 1434 with the de facto seigniory of the Medici. This fragility, however, was not felt by contemporaries, who rather praised the reaffirmation of prestige, according to the "civil" humanism of the republic's chancellors such as Coluccio Salutati. The appreciation of local tradition and the Roman origins of the city led again to the rejection of the courtly models, which had already been tried out, for example, in nearby Siena in the 14th century. In architecture, classical design already manifested itself with the construction of the Loggia della Signoria (1376-1382), with its wide round arches in the midst of the Gothic era; in sculpture, a greater adherence to classical plasticity was sought, as in the decoration of the Porta della Mandorla (1391-1397, then 1404-1406 and later) of the Cathedral, by Nanni di Banco and others; in painting, adherence to Giotto's style remained strong, with little further development.[20]

Toward the end of the 14th century, people began to tire of the old models and two main paths to renewal appeared: embrace the International Style or develop classical roots with even greater rigor. An extraordinary synthesis of the two schools of thought is offered by the two surviving panels from the 1401 competition for the north door of the Baptistery of Florence, cast in bronze by Lorenzo Ghiberti and Filippo Brunelleschi respectively and now in the Bargello National Museum. The test was to depict the Binding of Isaac within a quatrefoil, like those already used by Andrea Pisano in the older gate, which the two artists resolved very differently.[20]

Ghiberti divided the scene into two vertical bands harmonized by a rocky spur of archaic flavor, with a balanced narrative, proportionate figures and updated to Gothic cadences. He also included generic quotations from "antiquity" with a Hellenistic flavor, as in the powerful nude of Isaac, thus mediating between the stimuli available at the time. The use of the rocky background also generated a fine chiaroscuro, which "enveloped" the figures without violent breaks (which also influenced Donatello's stiacciato).[21]

Quite different was the relief created by Brunelleschi, who divided the scene into two horizontal bands, with overlapping planes creating a pyramidal composition. At the apex, behind a flat background where the figures violently emerge, is the climax of the sacrifice episode, where perpendicular lines create the collision between the three different wills (of Abraham, Isaac and the angel, who grasps Abraham's armed arm to stop him). The scene is rendered with such expressiveness that Ghiberti's tile looks like a calm recitation by comparison. This style derives from a meditation on the work of Giovanni Pisano (as in the Slaughter of the Innocents in the pulpit of St. Andrew) and on ancient art, as evidenced also by the mention of the spinario in the left corner. The victory fell to Ghiberti, a sign of how Florence was not yet ready for the innovative classicism that was at the origin of the Renaissance, precisely in sculpture before painting. In 1414, while working on the bronze gate, he produced a St. John the Baptist with a falling cloak with a large rhythmic stride, canceling out the forms of the body, just as was done by contemporary Bohemian masters.[21]

In painting, Gherardo Starnina's trip to Valencia in 1380 was of considerable importance; having brought himself up to date with international innovations, when he returned to Florence he had a strong influence on the new generation of painters such as Lorenzo Monaco and Masolino da Panicale. Lorenzo Monaco, a Camaldolese painter and miniaturist, painted, from 1404, elongated figures covered in broad drapery, with refined and unnaturally bright hues. However, he did not adhere to the secular courtly culture; rather, he lavished his works with a strong spirituality accentuated by the detachment of the figures from reality and by the aristocratic gestures that are only slightly hinted at. Masolino da Panicale was a sensitive and gifted interpreter, only recently reevaluated by critics because of the canonical comparison with the works of his "pupil" Masaccio: a mutual influence between the two has now been pointed out, not only from Masaccio to Masolino.[22]

Gentile da Fabriano also lived in Florence for a time, leaving behind his masterpiece, the Adoration of the Magi (1423), commissioned by the wealthiest citizen, Palla Strozzi, for his chapel. The later Quaratesi Polyptych already shows an influence related to Masaccio's isolated monumentality.[23]

Siena

[edit]

In Siena, artists of the first half of the 15th century elaborated on the prestigious local tradition, which had been among the founding contributions of the late Gothic style at the papal court in Avignon, while grafting some Florentine elements and maintaining a composed sense of religiosity.

The leader of this period is Sassetta, who painted works with figures that have a typically elongated silhouette. The light is clear and sharp, and the compositions are often original but measured. In the early part of his activity the attention to ornament and linear effects is very meticulous, while after 1440, when he worked, among other places, in Sansepolcro and probably saw the first works of Piero della Francesca, his painted panels became essential.[24]

Other important artists were the Master of the Osservanza, perhaps to be identified as Sano di Pietro, and Giovanni di Paolo, the latter linked to late Gothic Lombard and Flemish painting,[25] visible in the importance given to the landscape, which dominates the background, with careful definition of details even at a great distance (Madonna of Humility dated 1435). Gradually the stylistic features of the Renaissance permeated the Sienese artists, so much so that it seems extremely difficult to draw a line between the two styles, which in Siena in particular seem to merge seamlessly. Examples of this are some works by Giovanni di Paolo himself, attached to tradition but with Renaissance elements such as the use of perspective.

Abruzzo

[edit]

In Abruzzo the late Gothic period was influenced by artists from other areas, such as Gentile da Fabriano, who was called to paint a fresco in San Flaviano (c. 1420), L'Aquila. Among the adherents was the Master of the Beffi Triptych, perhaps the leading Abruzzese exponent.[26] In the Peligna-Marsica area, on the other hand, Giovanni da Sulmona, a painter and sculptor who also worked in the Marsica region, stood out.[27] There were two important artists in the province of Teramo: Jacobello del Fiore (of Venetian origin) and Antonio Martini of Atri, who, formed in Siena and the Emilian area, is documented throughout the whole of Abruzzo.

Late Gothic goldsmithing had its center in Sulmona, where a veritable school was established whose artists also worked outside the region (as evidenced by their works in Montecassino, Venafro, Apulia and parts of central Italy).[28] A prominent figure was Nicola da Guardiagrele, a goldsmith and painter trained at the school of Ghiberti in Florence and the proponent in his region of an interesting blend of Gothic and Renaissance.

-

Gothic portal of the Sulmona City Museum, circa 1415

-

Nave of Santa Maria Maggiore, Lanciano

-

Rose window of Santa Maria Maggiore, Lanciano

Naples

[edit]

In the Angevin, first, and later the Aragonese court of Naples, many foreign artists worked, making the city a point of artistic exchange and interaction. Among the most significant were the Catalan Jaime Baço, the Veronese Pisanello and the French Jean Fouquet. Prominent among local artists was Colantonio.[29] The traditional alliance between the Angevin kings and their French cousins made possible for nearly two centuries the construction of many religious and civil buildings of typically Gothic-French workmanship.

After the mid-15th century, with René of Anjou, the works of the Flemish masters arrived in the city, maturing an adherence to the Northern-inspired Renaissance, with the presence in the city of artists such as Antonello da Messina. René of Anjou was also the commissioner of an illustrated codex called Livre du coeur d'amour epris, which was probably begun in Naples and completed after his exile in Tarascon.

With the Aragonese, patronage remained typically Gothic, and Catalan Gothic blended with French Gothic and the emerging Renaissance style. For a spread of the Renaissance style one had to wait until the 1570s and 1580s.

-

Apse in Forcella.

-

Cross vaults of Sant'Eligio.

-

The main facade of Sant'Eligio.

-

Cathedral apse, the windows are walled up today.

-

Fresco depicting St. William of Gellone in a cycle dedicated to his story, in Castel Nuovo (Naples).

-

Gothic portal of the Penne Palace, the only surviving 15th-century element of the entire structure.

-

Detail of the Lilies of France on the Palace portal, Naples 15th century.

-

Castel Nuovo in Naples, Hall of the Barons, 15th century.

-

Castelnuovo of Naples, Hall of the Barons, 15th century.

-

Hours of Alfonso the Magnanimous, 1450 Naples; National Library.

-

Colantonio, Saint Vincent Ferrer and stories of his life, 1456-57

Sicily

[edit]

In Sicily, with the settlement of Ferdinand I (1412) and Alfonso V of Aragon (who in 1416 made it his base for the conquest of the Kingdom of Naples), there was a rapid artistic flowering favored first and foremost by the rich and demanding royal patronage and the system of trade and cultural exchanges with Catalonia, Valencia, Provence, northern France and the Netherlands.[17]

The finest work of this era was the fresco of the Triumph of Death for the courtyard of the Sclafani Palace (now detached and preserved in the Regional Gallery of Palermo), probably commissioned directly by the sovereign and characterized by a lofty quality unprecedented in the area. In a garden, Death bursts in, on a ghostly skeleton horse, and shoots arrows that strike people from all walks of life and different religions, killing them. The iconography is not new, and the attention to the most grotesque and macabre details reveals a transalpine hand. The expressiveness is extraordinary, with many secondary episodes of remarkable preciousness: musicians and hunters who continue their activities undaunted, characters barely surprised by death, and the sorrowful humbler characters who invoke Death but are ignored by it.[17]

With the personal union of the Kingdom of Sicily and that of Naples, the island lost the impulse of a political center to stimulate its own artistic activity. The local tradition thus continued to repeat itself, especially in architecture and sculpture, renewing itself superficially and taking in some elements of the new styles in isolation.[30]

-

Palace of Taormina.

-

Frederick's Tower.

-

Gothic facade of the Abatellis Palace, Palermo.

-

Detail of the Palace's Gothic gateway.

-

Gothic windows in Sicily.

-

Palace Tower.

-

Remnant entrance arch of the ancient church of San Giovanni de' Fleres, Catania.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ De Vecchi & Cerchiari (1999, p. 2).

- ^ Zuffi (2004, p. 14).

- ^ a b c De Vecchi & Cerchiari (1999, p. 8).

- ^ De Vecchi-Cerchiari, Volume 1, pag. 409.

- ^ a b De Vecchi & Cerchiari (1999, p. 9).

- ^ Carlo Perogalli (1987). "Gli affreschi della Sala dei Vizi e delle Virtù nel «Castello» di Masnago". Arte Lombarda. No. 80/81/82. pp. 73–83.

- ^ Carlo Cairati (2021). Pavia viscontea. La capitale regia nel rinnovamento della cultura figurativa lombarda. Vol. 1: castello tra Galeazzo II e Gian Galeazzo (1359-1402). Milano: Scalpendi Editore. pp. 181–184.

- ^ a b De Vecchi & Cerchiari (1999, p. 10).

- ^ De Vecchi & Cerchiari (1999, p. 11).

- ^ Vincenzo di Castua entry (in Italian) in the Enciclopedia Treccani

- ^ a b De Vecchi & Cerchiari (1999, p. 12).

- ^ De Vecchi & Cerchiari (1999, p. 13).

- ^ a b c De Vecchi & Cerchiari (1999, p. 14).

- ^ "Loggia veneziana". 2014. Archived from the original on 2016-03-20. Retrieved 2024-03-05.

- ^ Renzo Zorzi (a cura di), La Sala Baronale del Castello della Manta, Edizioni Olivetti, 1992.

- ^ Zuffi (2004, p. 207).

- ^ a b c d De Vecchi & Cerchiari (1999, p. 18).

- ^ Cristiano Marchegiani, Il frontespizio in terracotta della pieve di San Ginesio. Una proposta gotica alemanna nella Marca di Martino V, in I da Varano e le arti, a cura di A. De Marchi e P. L. Falaschi, Atti del convegno internazionale di studi, Camerino, Palazzo Ducale, 4-6 ottobre 2001, Comune e Università degli Studi di Camerino, Ripatransone, Maroni Editore, 2003, vol. II, pp. 637-654.

- ^ "La Collegiata". Archived from the original on 23 June 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ a b De Vecchi & Cerchiari (1999, p. 15).

- ^ a b De Vecchi & Cerchiari (1999, p. 16).

- ^ De Vecchi & Cerchiari (1999, p. 17).

- ^ De Vecchi & Cerchiari (1999, p. 45).

- ^ Zuffi (2004, p. 209).

- ^ Marco Pierini (2004). Arte a Siena. Firenze. p. 85. ISBN 8881170787.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Maestro delle storie di San Silvestro". Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ^ "Museo Civico Sulmona". December 2017. Archived from the original on 2021-04-11. Retrieved 2024-03-05.

- ^ Regione Abruzzo. "Introduzione arte orafa". Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ Zuffi (2004, p. 204).

- ^ De Vecchi & Cerchiari (1999, p. 19).

Bibliography

[edit]- Liana Castelfranchi Vegas (1966). Il gotico internazionale in Italia. Roma: Editori Riuniti.

- Sergio Bettini (1996). Elia Bordignon Favero (ed.). Il gotico internazionale. Vicenza: Neri Pozza.

- De Vecchi, Pierluigi; Cerchiari, Elda (1999). I tempi dell'arte. Vol. 2. Milano: Bompiani. ISBN 88-451-7212-0.

- Zuffi, Stefano (2004). Il Quattrocento. Milano: Electa. ISBN 88-370-2315-4.