Punk visual art

Punk visual art is artwork associated with the punk subculture and the no wave movement. It is prevalent in punk rock album covers, flyers for punk concerts and punk zines, but has also been prolific in other mediums, such as the visual arts, the performing arts, literature and cinema.[1] Punk manifested itself "differently but consistently" in different cultural spheres.[2] Punk also led to the birth of several movements: new wave, no wave, dark wave, industrial, hardcore, queercore, etc., which are sometimes showcased in art galleries and exhibition spaces.[2] The punk aesthetic was a dominant strand from 1982 to 1986 in the many art galleries of the East Village of Manhattan.

History

[edit]In his book, Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the 20th Century, cultural critic Greil Marcus expands upon the historical influence of Dada, Lettrism and Situationism on punk aesthetics in the art and music of the 1980s and early 1990s. Marcus argues that artists in the 1960s and 1970s, particularly those surrounding the Situationist International artist and theorist Guy Debord spearheaded a movement fueled by alienation and "angry, absolute demands" on society and art that gave rise to the punk sensibility. At its core was a subculture of artistic rebellion.[3][4]

Aesthetics

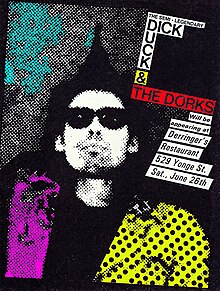

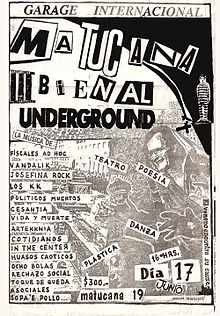

[edit]Characteristics associated with punk visual art is the usage of black or gray colors, and letters cut out from newspapers and magazines: a device previously associated with Dada collage and kidnap ransom notes. A prominent example of that style is the cover of the Sex Pistols Never Mind the Bollocks album designed by Jamie Reid. Images and figures are also sometimes cut and pasted from magazines and newspapers to create collages, album covers and paste-ups for posters that were often reproduced using copy machines.[3] Punk visual art often conveys a rejection of traditionalist values with self-derision that can be compared to Dada.[5]

In New York City

[edit]In New York City in the mid-1970s, there was much overlap between the punk music and the No wave downtown art scene. In 1978, many of the visual artists who were regulars at Tier 3, CBGB and other punk-related music venues participated in punk art exhibitions in New York.[6] Early punk art exhibits included the Colab organized The Times Square Show (1980)[7][8][9][10] and New York New Wave at PS1 (1981). Punk art found an ongoing home on the New York's lower east side with the establishment of several artist-run galleries such as ABC No Rio, FUN Gallery, Civilian Warfare, Nature Morte and Gracie Mansion Gallery. The art critic Carlo McCormick reviewed numerous exhibitions from this time in the East Village Eye.[11][12]

In the early 1980s, New York was on the verge of bankruptcy; the punk protest of the mid-1970s was transformed into a new artistic sensibility. It is in this context that Richard Hambleton arrives in New York. Drawing on the most visceral aspects of punk, he created "urban art" with the aim of constructing real experiences that provoke sensations of fear. Drawing on the poetic terrorism conceptualized by the Situationist movement, the creation of over 450 life-size black male figures in half-lit doorways and on the walls of dilapidated Manhattan buildings sought to provoke fear in passersby. Hambleton worked in the middle of the night and was never caught red-handed. His approach sought to confront preconceived notions of what art is and where it should be presented. "People expect to see balls in galleries (they do, sometimes). The work I do outside is somewhere between art and life," [13]

Notable artists

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Skov, Marie Arleth (2018-11-15). "The Art of the Enfants Terribles: Infantilism and Dilettantism in Punk Art". RIHA Journal.

- ^ a b Matt, Gerald (2008). No One Is Innocent: Punk: Art-Style-Revolt. Nürnberg. p. 7. ISBN 9783852470665.

- ^ a b Marcus, Greil (2009). Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674034808. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- ^ McWhirter, Cameron. "Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century". Harvard Review Online. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- ^ "In a Post-World: Post-Punk Art Now". The Invisible Dog Art Center. Retrieved 2022-03-12.

- ^ Masters, Marc (2007). No Wave. London: Black Dog Publishing. ISBN 978-1-906155-02-5

- ^ Goldstein, Richard, The First Radical Art Show of the '80s, Village Voice 16, June 1980, pp. 31-32

- ^ Levin, Kim, The Times Square Show, Arts September 1980, pp. 87-90

- ^ Deitch, Jeffrey, Report from Times Square, Art in America September 1980, pp. 58-63

- ^ Sedgwick, Susana, Times Square Show, East Village Eye Summer 1980, p. 21

- ^ Rosen, M. (25 September 2019). "The explosive rise–and inevitable fall of the East Village art scene". Document Journal.

- ^ Lippard, Lucy, Sex and Death and Shock and Schlock: A Long Review of The Times Square Show, by Anne Ominous in Post-modern Perspectives: Issues in Contemporary Art Ed. Howard Risatti. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1990, pp. 77-86

- ^ Beauchesne, Claudia Eve (2016). Post-Punk Art Now (PDF). PESOT - Organisme de création. p. 11. ISBN 978-2-9816126-0-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Alan Moore and Marc Miller, eds., ABC No Rio Dinero: The Story of a Lower East Side Art Gallery, NY, Colab, 1985

- Masters, Marc (2007). No Wave. London: Black Dog Publishing. ISBN 978-1-906155-02-5.

External links

[edit]- 98 Bowery: 1969-1989 - catalogue for a 1978 exhibition at the Washington Project for the Arts

- Everything's Punk in This Pop-Up Art Show - review of the 2016 exhibition at the Invisible Dog