Ethiopian art

Ethiopian art is the manifestation in art of the Ethiopian civilization. Primarily African Christian [1] civilization, Ethiopian art traditions have developed for millennia along side Christian Art the world over, and since the 7th century, the Islamic artistic traditions as well. The main artistic expressions have been architecture, painting, goldsmithing, and manuscript illuminations. There is also a range of traditions in textiles, many with woven geometric decoration, along side many more plain styles. [2]

Overview

[edit]

Prehistoric rock art comparable to that of other African sites survives in a number of places, and until the arrival of Christianity stone stelae, often carved with simple reliefs, were erected as grave-markers and for other purposes in many regions; Tiya is one important site. The "pre-Axumite" Iron Age culture of about the 5th century BCE to the 1st century CE was influenced by the Kingdom of Kush to the north, and settlers from Arabia, and produced cities with simple temples in stone, such as the ruined one at Yeha, which is impressive for its date in the 4th or 5th century BCE.

The powerful Kingdom of Aksum emerged in the 1st century BCE and dominated Ethiopia until the 10th century, has become very largely Christian from the 4th century.[3] Although some buildings and large, pre-Christian stelae exist, there appears to be no surviving Ethiopian Christian art from the Axumite period. However, the earliest works remaining show a clear continuity with Coptic art of earlier periods. There was considerable destruction of churches and their contents in the 16th century when Muslim neighbors invaded the country. The revival of art after this was influenced by Catholic European art in both iconography and elements of style but retained its Ethiopian character. In the 20th century, Western artists and architects began to be commissioned by the government, and to train local students, and more fully Westernized art was produced alongside continuations of traditional church art.[3]

Types

[edit]

Painting

[edit]

Church paintings in Ethiopia were likely produced as far back as the introduction of Christianity in the 4th century AD,[4] although the earliest surviving examples come from the church of Debre Selam Mikael in the Tigray Region, dated to the 11th century AD.[5] However, the 7th-century AD followers of the Islamic prophet Muhammad who fled to Axum in temporary exile mentioned that the original Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion was decorated with paintings.[5] Other early paintings include those from the rock-hewn churches of Lalibela, dated to the 12th century AD, and in nearby Geneta Maryam, dated to the 13th century AD.[5] However, paintings in illuminated manuscripts predate the earliest surviving church paintings; for instance, the Ethiopian Garima Gospels of the 4th-6th centuries AD contain illuminated scenes imitating the contemporary Byzantine style.[6]

Ethiopian painting, on walls, in books, and in icons,[7] is highly distinctive, though the style and iconography are closely related to the simplified Coptic version of Late Antique and Byzantine Christian art. It is typified by simplistic, almost cartoonish, figures with large, almond-shaped, eyes. Colours are usually bright and vivid. Most paintings are religious in nature, often decorating church walls and bibles. One of the best-known examples of this type of painting is at Debre Berhan Selassie in Gondar (pictured), famed for its angel-covered roof (angels in Ethiopian art are often represented as winged heads) as well as its other murals dating from the late 17th century. Diptychs and triptychs are also commonly painted with religious icons.[8] From the 16th century, Roman Catholic church art and European art in general began to exert some influence. However, Ethiopian art is highly conservative and retained much of its distinct character until modern times. The production of illuminated manuscripts for use continued up to the present day.[9] Pilgrimages to Jerusalem, where there has long been an Ethiopian clerical presence, also allowed some contact with a wider range of Orthodox art.

Churches may be very fully painted, although until the 19th century there is little sign of secular painting other than scenes commemorating the life of donors to churches on their walls. Unusually for Orthodox Christianity, icons were not usually kept in houses (where talismanic scrolls were often kept instead), but in the church. Some "diptychs" are in the form of an "ark" or tabot, in these cases consecrated boxes with a painted inside of the lid, placed closed on the altar during Mass, somewhat equivalent to the altar stone in the Western church, and the antimins in other Orthodox churches. These are regarded as so holy that the laity is not allowed to see them, and they are wrapped in cloth when taken in procession.

Ethiopian diptychs often have a primary wing with a frame. A smaller second wing, which is only the size of the image within the frame, is painted on both sides to allow closed and open views. Icons are painted on a wood base support, but since about the 16th century with intervening cloth support glued to a gesso layer above the wood. The binding medium for the paint is also animal-based glue, giving a matt finish which is then often varnished. A range of mostly mineral pigments is used, giving a palette based on reds, yellows, and blues. Underdrawing was used, which may remain visible or reinforced by painted edges to areas of colour in the final layer.

From the 15th century the Theotokos or Virgin Mary, with or without her Child, became increasingly popular. They used versions of a number of common Byzantine types, typically flanked by two archangels in iconic depictions. She is often depicted with a neighboring image of a mounted Saint George and the Dragon, who is regarded as especially linked to Mary in Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity, for carrying messages or intervening in human affairs on her behalf.

Crosses and other metalwork

[edit]

Another important form of Ethiopian art, also related to Coptic styles, is crosses made from wood and metal.[10][11] They are usually copper alloy or brass, plated (at least originally) with gold or silver. The heads are typically flat cast plates with elaborate and complex openwork decoration. The cross motif emerges from the decoration, with the whole design often forming a rotated square or circular shape, though the designs are highly varied and inventive. Many incorporate curved motifs rising from the base, which are called the "arms of Adam". Except in recent Western-influenced examples, they usually have no corpus, or figure of Christ, and the design often incorporates numerous smaller crosses. Engraved figurative imagery has sometimes been added. Crosses are mostly either processional crosses, with the metal head mounted on a long wooden staff, carried in religious processions and during the liturgy, or hand crosses, with a shorter metal handle in the same casting as the head. Smaller crosses worn as jewelry are also common.

The Lalibela Cross is an especially venerated hand cross, perhaps of the 12th century, which was stolen from a church in Lalibela in 1997 and eventually recovered and returned from a Belgian collector in 2001.

Distinctive forms of the crown were worn in ceremonial contexts by royalty and important noble officials, as well as senior clergy. Royal crowns rose high, with a number of circular bands, while church crowns often resemble an elongated version of the typical European closed crown, with four arms, joined at the top and surmounted by a cross.

Other arts and crafts

[edit]

Ethiopia has great ethnic and linguistic diversity, and styles in secular traditional crafts vary greatly in different parts of the country. There is a range of traditions in textiles, many with woven geometric decoration, although many types are also usually plain. Ethiopian church practices make a great deal of use of colourful textiles, and the more elaborate types are widely used as church vestments and as hangings, curtains, and wrappings in churches, although they have now largely been supplanted by Western fabrics. Examples of both types can be seen in the picture at the top of the article. Icons may normally be veiled with a semi-transparent or opaque cloth; very thin chiffon-type cotton cloth is a specialty of Ethiopia, though usually with no pattern.

Colourful basketry with a coiled construction is common in rural Ethiopia. The products have many uses, such as storing grains, seeds, and food and being used as tables and bowls. The Muslim city of Harar is well known for its high-quality basketry,[12] and many craft products of the Muslim minority relate to wider Islamic decorative traditions.

Illuminated Manuscripts from Other Religious Groups of Ethiopia

[edit]

Basketry wasn't the only artistry to emerge from the Muslim city of Harar. While Christian illuminated manuscripts dominate the literature on religious texts emerging from this region, Ethiopia is also home to a rich history of Islamic illuminated manuscripts. Located in central-eastern Ethiopia at the crossroads of multiple migration and trade routes, Harar became the epicentre for Islamization by the 14th century.[13] This followed previous introductions of the religion by Muslim religious figures in the northeast of the country in the 7th century, and coasts of neighboring Somalia in the 8th century.[14] The confluence of culture from both nomadic groups indigenous to the region and trade partners beyond, resulted in a style of manuscript unique to the Harari people.

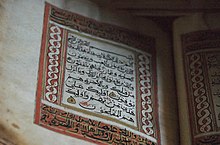

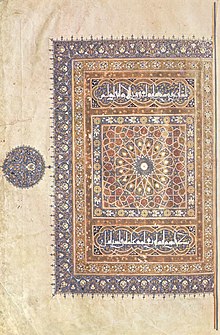

The Khalili manuscript (a single-volume Qur’ān of 290 folios) is regarded by scholar Dr. Sana Mirza as representative of distinct Harari codices (known in Arabic as Mus'haf). In part, because of its stylistic parallels to the 25 recorded collections produced in Harar.[15] Additionally, because it is one of the earliest documented texts from the city—the oldest datable manuscript containing text in Old Harari was produced in 1460.[16] The Khalili Qur’ān has distinct, wide horizontal margins, creating the optics of a script elongated across the page. The wide margins are filled with notes and ornate decorations. Some notes are written diagonally to the main text creating a vertical zigzagging effect, and others are written in blocking patterns. The colourful gray, gold, and red text serve both an aesthetic and functional purpose, each colour indicating a different reading of the text or sayings of the prophet.[15]

Ajami Script and Ajamization of Ethiopian Art

[edit]The text itself is written in Ajami, differing from the native Ge'ez script—an alphabet used to write languages local to Ethiopia and Eritrea. Ajami refers to an adapted Arabic script influenced by local languages primarily spoken in Eastern Africa.[14] Beyond the script, Ajami represents the contextual enrichment of Islamic traditions within the region during this period more broadly, a process growing literature on the subject refers to as Ajamization.[13][14] With the introduction of Islamic texts, culture, and art to Africa, communities modified these traditions to accommodate local palates. The Ajamization of Qur’ānic texts by the Harari people, reflects this intersection of assimilation and preservation, through adapting traditional Islamic practices to indigenous culture and taste.

Stylistic Parallels

[edit]Transcultural parallels and adaptations in the illumination of the text, such as the Byzantine influence on Christian illustrations within the region, can also be observed in Islamic art. Beyond visual likeness to Byzantine art, Ethiopia's geographic positioning in the Horn of Africa at the junction of the Mediterranean, Red Sea, and the Indian Ocean is reflected in the aesthetic similarities between Harari script and other visual cultures.[15] Notably, Dr. Mirza has drawn parallels between the Harari manuscripts and the decorative devices from the Islamic texts of the Mamluk Sultanate (modern-day Egypt and Syria) and the calligraphic letterform of the Biḥārī script (northeast India).[15]

Representation of Ethiopian Islamic Art

[edit]The lack of representation for Islamic manuscripts compared to other religious texts from Ethiopia in mainstream scholarship can be attributed to a variety of reasons. A leading scholar in Islamic manuscript cultures in Sub-Saharan Africa, Dr. Alessandro Gori, ascribes this disproportionate representation within academia to a variety of socio-political factors. Dr. Gori claims that a change in regime in 1991 and the geopolitics of "classical" Arabic studies have contributed to an understudied field.[17]

Research on Islam is also limited due to private ownership. The most prominent Ethiopian institutions to house these manuscripts include the Institute of Ethiopian Studies, the National Museum of Ethiopia, and the Harar National Museum.[18] Yet, the majority of these collections remain in private hands. The emergence of tourism in the 1970s brought foreign buyers with little knowledge of the historical relevance of these bodies of work.[17] This privatization made it easier for collectors from Europe, the United States, and Arab countries to acquire these texts without going through institutional channels.[18] In conjunction with the destruction of manuscripts by foreign aggressors or disputing citizens,[17] lack of trust in government bodies, and smuggling;[18] cataloging and preserving these sacred texts remains a difficult task.

Despite these challenges, academics, curators, and the Ethiopian government have made increasing efforts to inventory Harari and other Islamic manuscripts. In collaboration with the Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Dr. Gori published a catalog of Islamic codices in 2014 to help facilitate future research on these manuscripts.[17]

Gallery

[edit]-

Stone statue from Addi-Galamo, Tigray Province, 6th - 5th century BCE

-

Stelae in the royal cemetery at Tiya

-

The Obelisk of Axum, 4th century

-

12th-century processional cross

-

Bible from a monastery on Lake Tana, 12th-13th century

-

Page from Gunda Gunde Gospel, c. 1540

-

Small pendant diptych icon with St George and the Virgin and Child, late 18th century

-

Guardian angel, around 1800

-

Folding book

-

19th-century pendant cross

-

The roof of Debre Berhan Selassie church

-

Folding Processional Icon in the Shape of a Fan

-

Painting of Solomon, Ethiopian Chapel in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

-

Mary with Child, Ethiopian, Early 16th century

-

Ethoipian Orthodox Icon, Early 16th century

-

Ethiopian Orthodox Icon, Late 17th-early 18th century

-

Marian Scenes, c.a. 1630-1700

-

Mary with Child, Mid-late 17th century

-

Pendant Icon, Mary with Child and St. George, 17th century

-

Diptych: Christ crowned with thorns; descent from the Cross (c.a. 1750)

-

Mary with Child, and St. George (15th-16th century)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Hansberry, William Leo. Pillars in Ethiopian History; the William Leo Hansberry African History Notebook. Washington: Howard University Press, 1974. Fuente citada en Christianity in Ethiopia. Mathurin Veyssière de Lacroze, João Bermudez « Histoire du christianisme d'Éthiopie et d'Arménie », Vve Le Vier et P. Paupie, 1739, (ASIN B001BMUX7G). Fuente citada en Christianisme en Éthiopie. CIA World Factbook. Fuente citada en Religion in Ethiopia. Véase también Etiopía#religión, iglesia ortodoxa etíope, iglesia católica etíope e iglesia ortodoxa copta.

- ^ Jacques Mercier, en Gérard Prunier, L'Éthiopie contemporaine, Karthala, 2007, pgs. 257-260.

- ^ a b Biasio 2003.

- ^ "Christian Ethiopian art". Smarthistory. 2016-12-22. Retrieved 2017-07-27.

- ^ a b c Briggs, Philip (2015). Ethiopia. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 242. ISBN 978-1-84162-922-3.

- ^ De Lorenzi, James (2015). Guardians of the Tradition: Historians and Historical Writing in Ethiopia and Eritrea. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-1-58046-519-9.

- ^ Gossage, Carolyn; Chojnacki, Stanley (2000). Ethiopian icons: catalogue of the collection of the Institute of Ethiopian studies, Addis Ababa university. Skira. ISBN 978-88-8118-646-4. OCLC 848786240.[page needed]

- ^ "Ethiopia, its Art and Icons". Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ^ Ross 2002.

- ^ Chojnacki, Stanisław; Gossage, Carolyn (2006). Ethiopian crosses: a cultural history and chronology. Skira. ISBN 978-88-7624-831-3. OCLC 838853616.[page needed]

- ^ Evangelatou, Maria (2018). A Contextual Reading of Ethiopian Crosses through Form and Ritual. Gorgias Press. doi:10.31826/9781463240226. ISBN 978-1-4632-4022-6. S2CID 198628084.[page needed]

- ^ "Ethiopian Handicraft". Archived from the original on 1 July 2012. Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ^ a b Fani, Sara (17 October 2017). "Scribal Practices in Arabic Manuscripts from Ethiopia: The ʿAjamization of Scribal Practices in Fuṣḥā and ʿAjamī Manuscripts from Harar". Islamic Africa. 8 (1–2): 144–170. doi:10.1163/21540993-00801002.

- ^ a b c Hernández, Adday (17 October 2017). "The ʿAjamization of Islam in Ethiopia through Esoteric Textual Manifestations in Two Collections of Ethiopian Arabic Manuscripts". Islamic Africa. 8 (1–2): 171–192. doi:10.1163/21540993-00801004. hdl:10261/204784.

- ^ a b c d Mirza, Sana (28 December 2017). "The visual resonances of a Harari Qur'ān: An 18th century Ethiopian manuscript and its Indian Ocean connec". Afriques (8). doi:10.4000/afriques.2052.

- ^ Gori 2019.

- ^ a b c d Gori, Regourd & Delamarter 2014, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b c Kawo, Hassen Muhammad (2015). "Islamic Manuscript Collections in Ethiopia". Islamic Africa. 6 (1–2): 192–200. doi:10.1163/21540993-00602012. JSTOR 90017383.

References

[edit]- Biasio, Elisabeth (2003). "Ethiopia and Eritrea". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T026878. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.

- Gossage, Carolyn; Chojnacki, Stanley (2000). Ethiopian icons: catalogue of the collection of the Institute of Ethiopian studies, Addis Ababa university. Skira. ISBN 978-88-8118-646-4. OCLC 848786240.

- Fani, Sara (2017). "Scribal Practices in Arabic Manuscripts from Ethiopia: The ʿAjamization of Scribal Practices in Fuṣḥā and ʿAjamī Manuscripts from Harar". Islamic Africa. 8 (1–2): 144–170. doi:10.1163/21540993-00801002. JSTOR 90017960.

- Gnisci, Jacopo. "Christian Ethiopian art." In Smarthistory (Accessed 27 July 2017).

- Gori, Alessandro (2019). "Text Collections in the Arabic Manuscript Tradition of Harar: The Case of the Mawlid Collection and of šayḫ Hāšim's al-Fatḥ al-Raḥmānī". The Emergence of Multiple-Text Manuscripts. pp. 59–74. doi:10.1515/9783110645989-003. ISBN 978-3-11-064598-9. S2CID 214291690.

- Gori, Alessandro; Regourd, Anne; Delamarter, Steve (2014). A handlist of the manuscripts in the Institute of Ethiopian Studies. Volume two, Volume two. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4982-1761-3. OCLC 1196177778.

- Hernández, Adday (2017). "The ʿAjamization of Islam in Ethiopia through Esoteric Textual Manifestations in Two Collections of Ethiopian Arabic Manuscripts". Islamic Africa. 8 (1–2): 171–172. doi:10.1163/21540993-00801004. hdl:10261/204784. JSTOR 90017961.

- Horowitz, Deborah Ellen (2001). Ethiopian Art: The Walters Art Museum. Third Millennium. ISBN 978-1-903942-02-4.

- Kawo, Hassen Muhammad (2015). "Islamic Manuscript Collections in Ethiopia". Islamic Africa. 6 (1–2): 192–200. doi:10.1163/21540993-00602012. JSTOR 90017383.

- Mirza, Sana (28 December 2017). "The visual resonances of a Harari Qur'ān: An 18th century Ethiopian manuscript and its Indian Ocean connec". Afriques (8). doi:10.4000/afriques.2052.

- Ross, Emma George (October 2002). "African Christianity in Ethiopia". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.