Genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people.[a][1]

Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by means such as "the disintegration of [its] political and social institutions, of [its] culture, language, national feelings, religion, and [its] economic existence".[2] During the struggle to ratify the Genocide Convention, powerful countries restricted Lemkin's definition to exclude their own actions from being classified as genocide, ultimately limiting it to any of five "acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group".[3]

Genocide has occurred throughout human history, even during prehistoric times, but is particularly likely in situations of imperial expansion and power consolidation. Therefore, it is usually associated with colonial empires and settler colonies, as well as with both world wars and repressive governments in the twentieth century. The colloquial understanding of genocide is heavily influenced by the Holocaust as its archetype and is conceived as innocent victims targeted for their ethnic identity rather than for any political reason. Genocide is widely considered to be the epitome of human evil and often referred to as the "crime of crimes"; consequently, events are often denounced as genocide.

Origins

Polish-Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin coined the term genocide between 1941 and 1943.[6][7] Lemkin's coinage combined the Greek word γένος (genos, "race, people") with the Latin suffix -caedo ("act of killing").[8] He submitted the manuscript for his book Axis Rule in Occupied Europe to the publisher in early 1942, and it was published in 1944 as the Holocaust was coming to light outside Europe.[6] Lemkin's proposal was more ambitious than simply outlawing this type of mass slaughter. He also thought that the law against genocide could promote more tolerant and pluralistic societies.[8] His response to Nazi criminality was sharply different from that of another international law scholar, Hersch Lauterpacht, who argued that it was essential to protect individuals from atrocities, whether or not they were targeted as members of a group.[9]

According to Lemkin, the central definition of genocide was "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" in which its members were not targeted as individuals, but rather as members of the group. The objectives of genocide "would be the disintegration of the political and social institutions, of culture, language, national feelings, religion, and the economic existence of national groups".[2] These were not separate crimes but different aspects of the same genocidal process.[10] Lemkin's definition of nation was sufficiently broad to apply to nearly any type of human collectivity, even one based on a trivial characteristic.[11] He saw genocide as an inherently colonial process, and in his later writings analyzed what he described as the colonial genocides occurring within European overseas territories as well as the Soviet and Nazi empires.[8] Furthermore, his definition of genocidal acts, which was to replace the national pattern of the victim with that of the perpetrator, was much broader than the five types enumerated in the Genocide Convention.[8] Lemkin considered genocide to have occurred since the beginning of human history and dated the efforts to criminalize it to the Spanish critics of colonial excesses Francisco de Vitoria and Bartolomé de Las Casas.[12] The 1946 judgement against Arthur Greiser issued by a Polish court was the first legal verdict that mentioned the term, using Lemkin's original definition.[13]

Crime

Development

According to the legal instrument used to prosecute defeated German leaders at the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, atrocity crimes were only prosecutable by international justice if they were committed as part of an illegal war of aggression. The powers prosecuting the trial were unwilling to restrict a government's actions against its own citizens.[15]

In order to criminalize peacetime genocide, Lemkin brought his proposal to criminalize genocide to the newly established United Nations in 1946.[15] Opposition to the convention was greater than Lemkin expected due to states' concerns that it would lead their own policies - including treatment of indigenous peoples, European colonialism, racial segregation in the United States, and Soviet nationalities policy - to be labeled genocide. Before the convention was passed, powerful countries (both Western powers and the Soviet Union) secured changes in an attempt to make the convention unenforceable and applicable to their geopolitical rivals' actions but not their own.[16] Few formerly colonized countries were represented and "most states had no interest in empowering their victims– past, present, and future".[17]

The result severely diluted Lemkin's original concept; he privately considered it a failure.[16] Lemkin's anti-colonial conception of genocide was transformed into one that favored colonial powers.[18][19] Among the violence freed from the stigma of genocide included the destruction of political groups, which the Soviet Union is particularly blamed for blocking.[20][21] Although Lemkin credited women's NGOs with securing the passage of the convention, the gendered violence of forced pregnancy, marriage, and divorce was left out.[22] Additionally omitted was the forced migration of populations—which had been carried out by the Soviet Union and its satellites, condoned by the Western Allies, against millions of Germans from central and Eastern Europe.[23]

Genocide Convention

Two years after passing a resolution affirming the criminalization of genocide, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Genocide Convention on 9 December 1948.[24] It came into effect on 12 January 1951 after 20 countries ratified it without reservations.[25] The convention defines genocide as:

... any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

- (a) Killing members of the group;

- (b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

- (c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

- (d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

- (e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.[3]

A specific "intent to destroy" is the mens rea requirement of genocide.[26] The issue of what it means to destroy a group "as such" and how to prove the required intent has been difficult for courts to resolve. The legal system has also struggled with how much of a group can be targeted before triggering the Genocide Convention.[27][28][29] The two main approaches to intent are the purposive approach, where the perpetrator expressly wants to destroy the group, and the knowledge-based approach, where the perpetrator understands that destruction of the protected group will result from his actions.[30][31] Intent is the most difficult aspect for prosecutors to prove;[32][33] the perpetrators often claim that they merely sought the removal of the group from a given territory, instead of destruction as such,[34] or that the genocidal actions were collateral damage of military activity.[35]

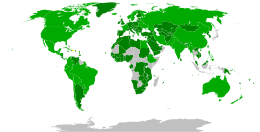

Attempted genocide, conspiracy to commit genocide, incitement to genocide, and complicity in genocide are criminalized.[36] The convention does not allow the retroactive prosecution of events that took place prior to 1951.[36] Signatories are also required to prevent genocide and prosecute its perpetrators.[37] Many countries have incorporated genocide into their municipal law, varying to a lesser or greater extent from the convention.[38] The convention's definition of genocide was adopted verbatim by the ad hoc international criminal tribunals and by the Rome Statute that established the International Criminal Court (ICC).[39] The crime of genocide also exists in customary international law and is therefore prohibited for non-signatories.[citation needed]

Prosecutions

During the Cold War, genocide remained at the level of rhetoric because both superpowers (the United States and the Soviet Union) felt vulnerable to accusations of genocide, and were therefore unwilling to press charges against the other party.[40] Despite political pressure to charge "Soviet genocide", the United States government refused to ratify the convention fearing countercharges.[41] Authorities have been reluctant to prosecute the perpetrators of many genocides, although non-judicial commissions of inquiry have also been created by some states.[42] The first conviction for genocide in an international court was in 1998 for a perpetrator of the Rwandan genocide. The first head of state to be convicted of genocide was in 2018 for the Cambodian genocide.[7] Although it is widely recognized that punishment of the perpetrators cannot be of an order with their crimes, the trials often serve other purposes such as attempting to shape public perception of the past.[42]

Genocide studies

The field of genocide studies emerged in the 1970s and 1980s, as social science began to consider the phenomenon of genocide.[43][44] Due to the occurrence of the Bosnian genocide, Rwandan genocide, and the Kosovo crisis, genocide studies exploded in the 1990s.[45] In contrast to earlier researchers who took for granted the idea that liberal and democratic societies were less likely to commit genocide, revisionists associated with the International Network of Genocide Scholars emphasized how Western ideas led to genocide.[46] The genocides of indigenous peoples as part of European colonialism were initially not recognized as a form of genocide.[47] Pioneers of research into settler colonialism such as Patrick Wolfe spelled out the genocidal logic of settler projects, prompting a rethinking of colonialism.[48] Many genocide scholars are concerned both with objective study of the topic, and obtaining insights that will help prevent future genocides.[49]

Definitions

The definition of genocide generates controversy whenever a new case arises and debate erupts as to whether or not it qualifies as a genocide. Sociologist Martin Shaw writes, “Few ideas are as important in public debate, but in few cases are the meaning and scope of a key idea less clearly agreed.”[51][52] Some scholars and activists use the Genocide Convention definition.[18] Others prefer narrower definitions that indicate genocide is rare in human history, reducing genocide to mass killing[53] or distinguishing it from other types of violence by the innocence,[4] helplessness, or defencelessness of its victims.[54] Most genocides occur during wartime,[55][56] and distinguishing genocide or genocidal war from non-genocidal warfare can be difficult.[56] Likewise, genocide is distinguished from violent and coercive forms of rule that aim to change behavior rather than destroy groups.[57][58] Some definitions include political or social groups as potential victims of genocide.[59] Many of the more sociologically oriented definitions of genocide overlap that of the crime against humanity of extermination, which refers to large-scale killing or induced death as part of a systematic attack on a civilian population.[60] Isolated or short-lived phenomena that resemble genocide can be termed genocidal violence.[61]

Cultural genocide or ethnocide—actions targeted at the reproduction of a group's language, culture, or way of life[62]—was part of Raphael Lemkin's original concept, and its proponents in the 1940s argued that it, along with physical genocide, were two mechanisms aiming at the same goal: destruction of the targeted group. Because cultural genocide clearly applied to some colonial and assimilationist policies, several states with overseas colonies threatened to refuse to ratify the convention unless it was excluded.[63] Most genocide scholars believe that both cultural genocide and structural violence should be included in the definition of genocide, if committed with intent to destroy the targeted group.[64] Although included in Lemkin's original concept and by some scholars, political groups were also excluded from the Genocide Convention. The result of this exclusion was that perpetrators of genocide could redefine their targets as being a political or military enemy, thus excluding them from consideration.[65]

Criticism of the concept of genocide and alternatives

Most civilian killings in the twentieth century were not from genocide, which only applies to select cases.[67][68] Alternative terms have been coined to describe processes left outside narrower definitions of genocide. Ethnic cleansing—the forced expulsion of a population from a given territory—has achieved widespread currency, although many scholars recognize that it frequently overlaps with genocide, even where Lemkin's definition is not used.[69] Other terms ending in -cide have proliferated for the destruction of particular types of groupings: democide (people by a government), eliticide (the elite of a targeted group), ethnocide (ethnic groups), gendercide (gendered groupings), politicide (political groups), classicide (social classes), and urbicide (the destruction of a particular locality).[70][71][72]

The word genocide inherently carries a value judgement[73] as it is widely considered to be the epitome of human evil.[74] In the past, violence that could be labeled genocide was sometimes celebrated[75]—although it always had its critics.[76] The idea that genocide sits on top of a hierarchy of atrocity crimes—that it is worse than crimes against humanity or war crimes—is controversial among scholars[77] and it suggests that the protection of groups is more important than of individuals.[78]

Causes

We have been reproached for making no distinction between the innocent Armenians and the guilty: but that was utterly impossible in view of the fact that those who are innocent today might be guilty tomorrow. The concern for the safety of Turkey simply had to silence all other concerns.

The colloquial understanding of genocide is heavily influenced by the Holocaust as its archetype and is conceived as innocent victims targeted because of racism rather than for any political reason.[4] Genocide is not an end of itself, but a means to another end—often chosen by perpetrators after other options failed.[81] Most are ultimately caused by its perpetrators perceiving an existential threat to their own existence, although this belief is usually exaggerated and can be entirely imagined.[82][83][84] Particular threats to existing elites that have been correlated to genocide include both successful and attempted regime change via assassination, coups, revolutions, and civil wars.[85]

Most genocides were not planned long in advance, but emerged through a process of gradual radicalization, often escalating to genocide following resistance by those targeted.[86] Genocide perpetrators often fear—usually irrationally—that if they do not commit atrocities, they will suffer a similar fate as they inflict on their victims.[87][88] Despite perpetrators' utilitarian goals,[89] ideological factors are necessary to explain why genocide seems to be a desirable solution to the identified security problem.[89][87] Noncombatants are harmed because of the collective guilt ascribed to an entire people—defined according to race but targeted because of its supposed security threat.[90] Other motives for genocide have included theft, land grabbing, and revenge.[3]

War is often described as the single most important enabler of genocide[91] providing the weaponry, ideological justification, polarization between allies and enemies, and cover for carrying out extreme violence.[92] A large proportion of genocides occurred under the course of imperial expansion and power consolidation.[93] Although genocide is typically organized around pre-existing identity boundaries, it has the outcome of strengthening them.[94] Although many scholars have emphasized the role of ideology in genocide, there is little agreement in how ideology contributes to violent outcomes;[95] others have cited rational explanations for atrocities.[89]

Perpetrators

Genocides are usually driven by states[96][97] and their agents, such as elites, political parties, bureaucracies, armed forces, and paramilitaries.[97] Civilians are often the leading agents when the genocide takes places in remote frontier areas.[98] A common strategy is for state-sponsored atrocities to be carried out in secrecy by paramilitary groups, offering the benefit of plausible deniability while widening complicity in the atrocities.[99][100][101] The leaders who organize genocide usually believe that their actions were justified and regret nothing.[102]

How ordinary people can become involved in extraordinary violence under circumstances of acute conflict is poorly understood.[103][104] The foot soldiers of genocide (as opposed to its organizers) are not demographically or psychologically aberrant.[105][106][107][108] People who commit crimes during genocide are rarely true believers in the ideology behind genocide, although they are affected by it to some extent[109] alongside other factors such as obedience, diffusion of responsibility, and conformity.[110] Other evidence suggests that ideological propaganda is not effective in inducing people to commit genocide[111] and that for some perpetrators, the dehumanization of victims, and adoption of nationalist or other ideologies that justify the violence occurs after they begin to perpetrate atrocities[112] often coinciding with escalation.[113] Although genocide perpetrators have often been assumed to be male, the role of women in perpetrating genocide—although they were historically excluded from leadership—has also been explored.[114] People's behavior changes under the course of events, and someone might choose to kill one genocide victim while saving another.[115][116][117] Anthropologist Richard Rechtman writes that in circumstances where atrocities such as genocides are perpetrated, many people refuse to become perpetrators, which often entails great sacrifices such as risking their lives and fleeing their country.[118]

Methods

It is a common misconception that genocide necessarily involves mass killing; indeed, it may occur without a single person being killed.[119]

Forced displacement is a common feature of many genocides, with the victims often transported to another location where their destruction is easier for the perpetrators. In some cases, victims are transported to sites where they are killed or deprived of the necessities of life.[120] People are often killed by the displacement itself, as was the case for many Armenian genocide victims.[121] Cultural destruction, such as that practised at Canadian boarding schools for indigenous children, is often dependent on controlling the victims at a specific location.[121] Destruction of cultural objects, such as religious buildings, is common even when the primary method of genocide is not cultural.[72] Cultural genocide, such as residential schools, is particularly common during settler-colonial consolidation.[122][123]

Men, particularly young adults, are disproportionately targeted for killing before other victims in order to stem resistance.[124][125] Although diverse forms of sexual violence—ranging from rape, forced pregnancy, forced marriage, sexual slavery, mutilation, forced sterilization—can affect either males or females, women are more likely to face it.[126] The combination of killing of men and sexual violence against women is often intended to disrupt reproduction of the targeted group.[124]

Almost all genocides are brought to an end either by the military defeat of the perpetrators or the accomplishment of their aims.[127]

Reactions

According to rational choice theory, it should be possible to intervene to prevent genocide by raising the costs of engaging in such violence relative to alternatives.[128] Although there are a number of organizations that compile lists of states where genocide is considered likely to occur,[129] the accuracy of these predictions are not known and there is no scholarly consensus over evidence-based genocide prevention strategies.[130] Intervention to prevent genocide has often been considered a failure[131][132] because most countries prioritize business, trade, and diplomatic relationships:[133][130] as a consequence, "the usual powerful actors continue to use violence against vulnerable populations with impunity".[132]

Responsibility to protect is a doctrine that emerged around 2000, in the aftermath of several genocides around the world, that seeks to balance state sovereignty with the need for international intervention to prevent genocide.[134] However, disagreements in the United Nations Security Council and lack of political will have hampered the implementation of this doctrine.[131] Although military intervention to halt genocide has been credited with reducing violence in some cases, it remains deeply controversial[135] and is usually illegal.[136] Researcher Gregory H. Stanton found that calling crimes genocide rather than something else, such as ethnic cleansing, increased the chance of effective intervention.[137] Perhaps for this reason, states are often reluctant to recognize crimes as genocide while they are taking place.

History

Lemkin applied the concept of genocide to a wide variety of events throughout human history. He and other scholars date the first genocides to prehistoric times.[138][139][12] Prior to the advent of civilizations consisting of sedentary farmers, humans lived in tribal societies, with intertribal warfare often ending with the obliteration of the defeated tribe, killing of adult males and integration of women and children into the victorious tribe.[140] Genocide is mentioned in various ancient sources including the Hebrew Bible.[141][142] The massacre of men and the enslavement or forced assimilation of women and children—often limited to a particular town or city rather than applied to a larger group—is a common feature of ancient warfare as described in written sources.[143][119] The events that some scholars consider genocide in ancient and medieval times had more pragmatic than ideological motivations.[144] As a result, some scholars such as Mark Levene argue that genocide is inherently connected to the modern state—thus to the rise of the West in the early modern era and its expansion outside Europe—and earlier conflicts cannot be described as genocide.[145][146]

Although all empires rely on violence, often extreme violence, to perpetuate their own existence, they also seek to preserve and rule the conquered rather than eradicate them.[147] Although the desire to exploit populations was a disincentive to extermination,[148] imperial rule could lead to genocide when resistance emerged.[147] Ancient and medieval genocides were often committed by empires.[144] Unlike traditional empires, settler colonialism—particularly associated with the settlement of Europeans outside of Europe—is characterized by militarized populations of settlers in remote areas beyond effective state control. Rather than labor or economic surplus, the settlers want to acquire land from indigenous people[149] making genocide more likely than with classical colonialism.[150] While the lack of law enforcement on the frontier ensured impunity for settler violence, the advance of state authority enabled settlers to consolidate their gains using the legal system.[151]

Genocide was committed on a large scale during both world wars. The prototypical genocide, the Holocaust, involved such large-scale logistics that it reinforced the impression that genocide was the result of civilization drifting off course and required both the "weapons and infrastructure of the modern state and the radical ambitions of the modern man".[152] Scientific racism and nationalism were common ideological drivers of many twentieth century genocides.[153] After the horrors of World War II, world leaders attempted to proscribe genocide via the Genocide Convention. Despite the promise of never again and the international effort to outlaw genocide, it has continued to occur repeatedly into the twenty-first century.[154]

Effects and aftermath

In the aftermath of genocide, common occurrences are the attempt to prosecute perpetrators through the legal system and obtain recognition and reparations for survivors, as well as reflection of the events in scholarship and culture, such as genocide museums.[155] Except in the case of the Holocaust, few genocide victims receive any reparations despite the trend of requiring such reparations in international and municipal law.[156] The perpetrators and their supporters often deny the genocide and reject responsibility for the harms suffered by victims.[157] Efforts to achieve justice and reconciliation are common in postgenocide situations, but are necessarily incomplete and inadequate.[77] The effects of genocide on societies are under-researched.[155]

Much of the qualitative research on genocide has focused on the testimonies of victims, survivors, and other eyewitnesses.[158] Studies of genocide survivors have examined rates of depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, suicide, post-traumatic stress disorder, and post-traumatic growth. While some have found negative results, others find no association with genocide survival.[159] There are no consistent findings that children of genocide survivors have worse health than comparable individuals.[160] Most societies are able to recover demographically from genocide, but this is dependent on their position early in the demographic transition.[161]

Because genocide is often perceived as the "crime of crimes", it grabs attention more effectively than other violations of international law.[162] Consequently, victims of atrocities often label their suffering genocide as an attempt to gain attention to their plight and attract foreign intervention.[163] Although remembering genocide is often perceived as a way to develop tolerance and respect for human rights,[citation needed] the charge of genocide often leads to increased cohesion among the targeted people—in some cases, it has been incorporated into national identity—and stokes enmity towards the group blamed for the crime, reducing the chance of reconciliation and increasing the risk of future occurrence of genocide.[78][82] Some genocides are commemorated in memorials or museums.[164]

References

- ^ Kiernan et al. 2023, p. 11.

- ^ a b Bachman 2022, p. 48.

- ^ a b c Kiernan 2023, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Moses 2023, p. 19.

- ^ Shaw 2015, Conclusion of Chapter 4.

- ^ a b Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 7.

- ^ a b Kiernan 2023, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 14.

- ^ Ochab & Alton 2022, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Shaw 2015, p. 39.

- ^ Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 15.

- ^ a b Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 11.

- ^ Irvin-Erickson 2023, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Weiss-Wendt 2017, pp. 267–268.

- ^ a b Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 20.

- ^ a b Irvin-Erickson 2023, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Bachman 2021b, p. 1021.

- ^ a b Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 22.

- ^ Bachman 2021b, p. 1020.

- ^ Weiss-Wendt 2017, p. 4.

- ^ Bachman 2022, p. 53.

- ^ Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 8.

- ^ Weiss-Wendt 2017, pp. 267–268, 283.

- ^ Weiss-Wendt 2017, p. 3.

- ^ Weiss-Wendt 2017, p. 158.

- ^ Schabas 2010, pp. 136, 138.

- ^ Ozoráková 2022, pp. 292–295.

- ^ Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 13.

- ^ Schabas 2010, p. 136.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, p. 35.

- ^ Jones 2023, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Kiernan, Madley & Taylor 2023, pp. 4, 9.

- ^ Ochab & Alton 2022, pp. 28, 30.

- ^ Bachman 2022, p. 57.

- ^ Bachman 2022, p. 47.

- ^ a b Kiernan, Madley & Taylor 2023, p. 2.

- ^ Ochab & Alton 2022, p. 32.

- ^ Schabas 2010, p. 123.

- ^ Ozoráková 2022, p. 281.

- ^ Weiss-Wendt 2017, p. 9.

- ^ Weiss-Wendt 2017, p. 266.

- ^ a b Stone 2013, p. 150.

- ^ Kiernan et al. 2023, pp. 13, 17.

- ^ Jones 2023, p. 23.

- ^ Kiernan et al. 2023, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Kiernan et al. 2023, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Kiernan, Madley & Taylor 2023, p. 6–10.

- ^ Kiernan et al. 2023, p. 9.

- ^ Jones 2023, p. 24.

- ^ Moses 2021, pp. 443–444.

- ^ Shaw 2015, p. 38.

- ^ Williams 2020, p. 8.

- ^ Shaw 2014, p. 4.

- ^ Shaw 2015, Sociologists redefine genocide.

- ^ Mulaj 2021, p. 15.

- ^ a b Shaw 2014, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Shaw 2014, p. 7.

- ^ Kiernan, Madley & Taylor 2023, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Kiernan et al. 2023, p. 3.

- ^ Kiernan et al. 2023, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Shaw 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Bachman 2022, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Bachman 2022, p. 62.

- ^ Bachman 2021a, p. 375.

- ^ Bachman 2022, pp. 45–46, 48–49, 53.

- ^ Moses 2023, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Moses 2023, p. 25.

- ^ Graziosi & Sysyn 2022, p. 15.

- ^ Shaw 2015, Chapter 5.

- ^ Shaw 2015, Chapter 6.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, p. 33.

- ^ a b Jones 2023, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Lang 2005, pp. 5–17.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, p. 32.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b Mulaj 2021, p. 11.

- ^ a b Sands 2017, p. 364.

- ^ Ihrig 2016, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Moses 2023, p. 32.

- ^ Kathman & Wood 2011, pp. 737–738.

- ^ a b Stone & Jinks 2022, p. 258.

- ^ Moses 2023, pp. 16–17, 27.

- ^ Nyseth Nzitatira 2022, p. 52.

- ^ Nyseth Nzitatira 2022, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Jones 2023, pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b Stone 2013, p. 146.

- ^ Moyd 2022, p. 245.

- ^ a b c Maynard 2022, p. 308.

- ^ Moses 2021, p. 329.

- ^ Moyd 2022, p. 233.

- ^ Moyd 2022, pp. 236–239.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, p. 49.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, p. 50.

- ^ Maynard 2022, p. 307.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, pp. 36–37.

- ^ a b Weiss-Wendt 2022, p. 189.

- ^ Häussler, Stucki & Veracini 2022, pp. 215–216.

- ^ Anderson & Jessee 2020, p. 12.

- ^ Anderton 2023, p. 146.

- ^ Weiss-Wendt 2022, pp. 179–180, 189.

- ^ Weiss-Wendt 2022, p. 186.

- ^ Anderson & Jessee 2020, p. 3.

- ^ Rechtman 2021, p. 174.

- ^ Williams 2020, pp. 1–2, 211.

- ^ Anderson & Jessee 2020, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Rechtman 2021, p. 190.

- ^ Maynard 2022, p. 319.

- ^ Maynard 2022, p. 152.

- ^ McDoom 2020, p. 124.

- ^ Luft 2020, p. 4.

- ^ McDoom 2020, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Luft 2020, p. 5.

- ^ Kiernan et al. 2023, p. 10.

- ^ Anderton 2023, p. 143.

- ^ Rechtman 2021, p. 177.

- ^ Luft 2020, p. 2.

- ^ Rechtman 2021, pp. 181–182, 187, 191.

- ^ a b Jones 2023, The Origins of Genocide.

- ^ Basso 2024, p. 20.

- ^ a b Basso 2024, p. 21.

- ^ Häussler, Stucki & Veracini 2022, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Adhikari 2023, p. 43.

- ^ a b Basso 2024, p. 33.

- ^ von Joeden-Forgey 2022, p. 118.

- ^ von Joeden-Forgey 2022, pp. 116–119.

- ^ Bellamy & McLoughlin 2022, p. 303.

- ^ Kathman & Wood 2011, p. 738.

- ^ Nyseth Nzitatira 2022, pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b Nyseth Nzitatira 2022, p. 68.

- ^ a b Mulaj 2021, p. 16.

- ^ a b Moyd 2022, p. 250.

- ^ Ochab & Alton 2022, pp. 3, 41.

- ^ Bachman 2022, p. 119.

- ^ Mulaj 2021, p. 17.

- ^ Moses 2023, p. 21.

- ^ Ochab & Alton 2022, p. 43.

- ^ Naimark 2017, p. vii.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, p. 31.

- ^ Häussler, Stucki & Veracini 2022, pp. 203–204.

- ^ Naimark 2017, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, pp. 39, 50.

- ^ a b Lemos, Taylor & Kiernan 2023, p. 43.

- ^ Weiss-Wendt 2022, p. 170.

- ^ Jones 2023, p. 84.

- ^ a b Häussler, Stucki & Veracini 2022, pp. 219–220.

- ^ Häussler, Stucki & Veracini 2022, p. 211.

- ^ Häussler, Stucki & Veracini 2022, pp. 212–213.

- ^ Häussler, Stucki & Veracini 2022, pp. 218–219.

- ^ Adhikari 2023, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Kiernan et al. 2023, p. 7.

- ^ Kiernan et al. 2023, p. 8.

- ^ Ochab & Alton 2022, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b Mulaj 2021, p. 2.

- ^ Mulaj 2021, p. 24.

- ^ Mulaj 2021, pp. 2, 16.

- ^ Anderson & Jessee 2020, p. 7.

- ^ Lindert et al. 2019, p. 2.

- ^ Lindert et al. 2017, p. 246.

- ^ Kugler 2016, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Moses 2023, p. 22.

- ^ Moses 2023, p. 23.

- ^ Stone 2013, p. 151.

Bibliography

Books

- Bachman, Jeffrey S. (2022). The Politics of Genocide: From the Genocide Convention to the Responsibility to Protect. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-1-9788-2147-7.

- Basso, Andrew R. (2024). Destroy Them Gradually: Displacement as Atrocity. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-1-9788-3130-8.

- Ihrig, Stefan (2016). Justifying Genocide: Germany and the Armenians from Bismarck to Hitler. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-50479-0.

- Jones, Adam (2023). Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-000-95870-6.

- Maynard, Jonathan Leader (2022). Ideology and Mass Killing: The Radicalized Security Politics of Genocides and Deadly Atrocities. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-108266-5.

- Moses, A. Dirk (2021). The Problems of Genocide: Permanent Security and the Language of Transgression. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-02832-5.

- Naimark, Norman M. (2017). Genocide: A World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-976527-0.

- Ochab, Ewelina U.; Alton, David (2022). State Responses to Crimes of Genocide: What Went Wrong and How to Change It. Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-030-99162-3.

- Rechtman, Richard (2021). Living in Death: Genocide and Its Functionaries. Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0-8232-9788-7.

- Sands, Philippe (2017). East West Street: On the Origins of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-1-4746-0191-7.

- Shaw, Martin (2014). Genocide and International Relations: Changing Patterns in the Transitions of the Late Modern World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-11013-6.

- Shaw, Martin (2015). What is Genocide?. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-7456-8710-0.

- Weiss-Wendt, Anton (2017). The Soviet Union and the Gutting of the UN Genocide Convention. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-31290-9.

- Williams, Timothy (2020). The Complexity of Evil: Perpetration and Genocide. Rutgers University Press. hdl:20.500.12657/52460. ISBN 978-1-9788-1431-8.

Collections

- Anderson, Kjell; Jessee, Erin (2020). "Introduction". Researching Perpetrators of Genocide. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-32970-9.

- Bachman, Jeffrey (2021b). "Genocide and Imperialism". The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Imperialism and Anti-Imperialism. Springer International Publishing. pp. 1012–1022. ISBN 978-3-030-29901-9.

- Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk, eds. (2010). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-161361-6.

- Schabas, William A. "The Law and Genocide". In Bloxham & Moses (2010), pp. 123–141.

- Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk, eds. (2022). Genocide: Key Themes. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-286526-7.

- Nyseth Nzitatira, Hollie. "Predicting genocide". In Bloxham & Moses (2022), pp. 45-74.

- von Joeden-Forgey, Elisa. "Gender and genocide". In Bloxham & Moses (2022), pp. 100-131.

- Weiss-Wendt, Anton. "The state and genocide". In Bloxham & Moses (2022), pp. 161–190.

- Häussler, Matthias; Stucki, Andreas; Veracini, Lorenzo. "Genocide and empire". In Bloxham & Moses (2022), pp. 191–221.

- Moyd, Michelle. "Genocide and War". In Bloxham & Moses (2022), pp. 222–252.

- Stone, Dan; Jinks, Rebecca. "Genocide and memory". In Bloxham & Moses (2022), pp. 253–276.

- Bellamy, Alex J.; McLoughlin, Stephen. "Genocide and Military Intervention". In Bloxham & Moses (2022).

- Graziosi, Andrea; Sysyn, Frank E. (2022). "Introduction: Genocide and Mass Categorical Violence". In Graziosi, Andrea; Sysyn, Frank E. (eds.). Genocide: The Power and Problems of a Concept. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 3–21. ISBN 978-0-2280-0951-1.

- Kiernan, Ben; Lemos, T. M.; Taylor, Tristan S., eds. (2023). The Cambridge World History of Genocide: Volume 1, Genocide in the Ancient, Medieval and Premodern Worlds. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-64034-3.

- Kiernan, Ben. "General Editor’s Introduction to the Series: Genocide: Its Causes, Components, Connections and Continuing Challenges". In Kiernan, Lemos & Taylor (2023), pp. 1–30.

- Lemos, T. M.; Taylor, Tristan S.; Kiernan, Ben. "Introduction to Volume I". In Kiernan, Lemos & Taylor (2023), pp. 31–56.

- Kiernan, Ben; Madley, Benjamin; Taylor, Rebe (2023). "Introduction to Volume II". In Blackhawk, Ned; Kiernan, Ben; Madley, Benjamin; Taylor, Rebe (eds.). The Cambridge World History of Genocide. Vol. II: Genocide in the Indigenous, Early Modern and Imperial Worlds, from c.1535 to World War One. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–20. doi:10.1017/9781108765480. ISBN 978-1-108-76548-0.

- Kiernan, Ben; Lower, Wendy; Naimark, Norman; Straus, Scott (2023). "Introduction to Volume III". The Cambridge World History of Genocide: Volume 3: Genocide in the Contemporary Era, 1914–2020. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–28. ISBN 978-1-108-76711-8.

- Kugler, Tadeusz (2016). "The Demography of Genocide". Economic Aspects of Genocides, Other Mass Atrocities, and Their Preventions. Oxford University Press. pp. 102–124. ISBN 978-0-19-937829-6.

- Lang, Berel (2005). "The Evil in Genocide". Genocide and Human Rights: A Philosophical Guide. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 5–17. ISBN 978-0-230-55483-2.

- Moses, A. Dirk (2023). "Genocide as a Category Mistake: Permanent Security and Mass Violence Against Civilians". Genocidal Violence: Concepts, Forms, Impact. De Gruyter. pp. 15–38. doi:10.1515/9783110781328-002. ISBN 978-3-11-078132-8.

- Mulaj, Klejda (2021). "Introduction: Postgenocide: Living with Permutations of Genocide Harms". Postgenocide: Interdisciplinary Reflections on the Effects of Genocide. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-264825-9.

- Simon, David J.; Kahn, Leora, eds. (2023). Handbook of Genocide Studies. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-80037-934-3.

- Irvin-Erickson, Douglas. "The history of Rapha'l Lemkin and the UN Genocide Convention". In Simon & Kahn (2023), pp. 7–26.

- Adhikari, Mohamed. "Destroying to replace: reflections on motive forces behind civilian-driven violence in settler genocides of Indigenous peoples". In Simon & Kahn (2023), pp. 42–53.

- Anderton, Charles H. "Genocide prevention: perspectives from psychological and social economic choice models". In Simon & Kahn (2023), pp. 142–156.

- Stone, Dan (2013). "Genocide and Memory". The Holocaust, Fascism and Memory: Essays in the History of Ideas. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 143–156. ISBN 978-1-137-02953-9.

Journals

- Bachman, Jeffrey S (2021a). "Situating Contributions from Underrepresented Groups and Geographies within the Field of Genocide Studies". International Studies Perspectives. 22 (3): 361–382. doi:10.1093/isp/ekaa011.

- Kathman, Jacob D.; Wood, Reed M. (2011). "Managing Threat, Cost, and Incentive to Kill: The Short- and Long-Term Effects of Intervention in Mass Killings". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 55 (5): 735–760. doi:10.1177/0022002711408006.

- Lindert, Jutta; Kawachi, Ichiro; Knobler, Haim Y.; Abramowitz, Moshe Z.; Galea, Sandro; Roberts, Bayard; Mollica, Richard; McKee, Martin (2019). "The long-term health consequences of genocide: developing GESQUQ - a genocide studies checklist". Conflict and Health. 13 (1): 14. doi:10.1186/s13031-019-0198-9. ISSN 1752-1505. PMC 6460659. PMID 31011364.

- Lindert, Jutta; Knobler, Haim Y.; Kawachi, Ichiro; Bain, Paul A.; Abramowitz, Moshe Z.; McKee, Charlotte; Reinharz, Shula; McKee, Martin (2017). "Psychopathology of children of genocide survivors: a systematic review on the impact of genocide on their children's psychopathology from five countries". International Journal of Epidemiology: 246–257.

- Luft, Aliza (2020). "Three Stories and Three Questions about Participation in Genocide". Journal of Perpetrator Research. 3 (1): 196–. doi:10.21039/jpr.3.1.37. ISSN 2514-7897.

- McDoom, Omar Shahabudin (2020). "Radicalization as cause and consequence of violence in genocides and mass killings". Violence: An International Journal. 1 (1): 123–143. doi:10.1177/2633002420904267. ISSN 2633-0024.

- Ozoráková, Lilla (2022). "The Road to Finding a Definition for the Crime of Genocide – the Importance of the Genocide Convention". The Law & Practice of International Courts and Tribunals. 21 (2): 278–301. doi:10.1163/15718034-12341475. ISSN 1569-1853.