Genocides in history (1946 to 1999)

| Part of a series on |

| Genocide |

|---|

|

| Issues |

| Related topics |

| Category |

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people[a] in whole or in part. The term was coined in 1944 by Raphael Lemkin. It is defined in Article 2 of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG) of 1948 as "any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group, as such: killing members of the group; causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; deliberately inflicting on the group's conditions of life, calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; [and] forcibly transferring children of the group to another group."[1]

The preamble to the CPPCG states that "genocide is a crime under international law, contrary to the spirit and aims of the United Nations and condemned by the civilized world", and it also states that "at all periods of history genocide has inflicted great losses on humanity."[1] Genocide is widely considered to be the epitome of human evil,[2] and has been referred to as the "crime of crimes".[3][4][5] The Political Instability Task Force estimated that 43 genocides occurred between 1956 and 2016, resulting in 50 million deaths.[6] The UNHCR estimated that a further 50 million had been displaced by such episodes of violence.[6]

Definitions of genocide

[edit]The debate continues over what legally constitutes genocide. One definition is any conflict that the International Criminal Court has so designated. Mohammed Hassan Kakar argues that the definition should include political groups or any group so defined by the perpetrator.[7] He prefers the definition from Frank Chalk and Kurt Jonassohn, which defines genocide as "a form of one-sided mass killing in which a state or other authority intends to destroy a group so defined by the perpetrator."[8]

In literature, some scholars have popularly emphasized the role that the Soviet Union played in excluding political groups from the international definition of genocide, which is contained in the Genocide Convention of 1948,[9] and in particular they have written that Joseph Stalin may have feared greater international scrutiny of the political killings that occurred in the country, such as the Great Purge;[10] however, this claim is not supported by evidence. The Soviet view was shared and supported by many diverse countries, and they were also in line with Raphael Lemkin's original conception,[b] and it was originally promoted by the World Jewish Congress.[12]

Post-World War II

[edit]Post–World War II Central and Eastern Europe

[edit]Ethnic cleansing of Germans

[edit]

After WWII ended in Europe, about 11–12 million[13][14][15] Germans were forced to flee from or were expelled from several countries throughout Eastern and Central Europe, including Russia, Romania, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Yugoslavia and the prewar territory of Poland.[16] A large number of them were also displaced when Germany's former eastern provinces either passed to Soviet Russia or became part of Poland in accordance with the Potsdam Agreement (Poland lost some of these territories in various periods over several centuries),[16] regardless of the fact that those lands had been under heavy German ethnic and cultural influence since the German colonization of them in the Late Middle Ages or the 19th century,[17][18][19] and the fact that they had been under German rule since the conquests and expansion of Brandenburg and Prussia. The majority of these expelled and displaced Germans ended up in what remained of Germany, with some of them being sent to West Germany and others being sent to East Germany.[20]

The ethnic cleansing of the Germans was the largest displacement of a single European population in modern history.[13][14] Estimates for the total number of those who died during the removals range from 500,000 to 2,000,000, where the higher figures include "unsolved cases" of persons reported as missing and presumed dead. Many German civilians were sent to internment and labor camps as well, where they often died.[where?] Usually, the events are either classified as a population transfer,[21][22] or they are classified as an ethnic cleansing.[23][24] Felix Ermacora, among a minority of legal scholars, equated ethnic cleansing with genocide,[25][26][page needed] and stated that the expulsion of the Germans therefore constituted genocide.[27]

Partition of India

[edit]The Partition of India was the partition of the British Indian Empire[28][page needed] that led to the creation of the sovereign states of the Dominion of Pakistan (which later split into Pakistan and Bangladesh) and the Dominion of India (later the Republic of India) on 15 August 1947. During the Partition, one of British India's provinces, the Punjab Province, was split along communal lines into West Punjab and East Punjab[29] (later split into the three separate modern-day Indian states of Punjab, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh). West Punjab was formed out of the Muslim majority districts of the former British Indian Punjab Province, while East Punjab was formed out of the Hindu and Sikh majority districts of the former province.[30][31]

Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs who had co-existed for a millennium attacked each other in what is argued to be a retributive genocide of horrific proportions,[32] accompanied by arson, looting, rape and the abduction of women. The Indian government claimed that 33,000 Hindu and Sikh women were abducted, and the Pakistani government claimed that 50,000 Muslim women were abducted during riots. By 1949, there were governmental claims that 12,000 women had been recovered in India and 6,000 women had been recovered in Pakistan.[33] By 1954 there were 20,728 recovered Muslim women and 9,032 Hindu and Sikh women recovered from Pakistan.[34]

This partition triggered what was one of the world's largest mass migrations in modern history.[35] Around 11.2 million people successfully crossed the India-West Pakistan border, mostly through the Punjab. 6.5 million Muslims migrated from India to West Pakistan and 4.7 million Hindus and Sikhs from West Pakistan arrived in India. However many people went missing.[citation needed]

A study of the total population inflows and outflows in the districts of the Punjab, using the data provided by the 1931 and 1951 Census has led to an estimate of 1.26 million missing Muslims who left western India but did not reach Pakistan.[29] The corresponding number of missing Hindus/Sikhs along the western border is estimated to be approximately 0.84 million.[29] This puts the total number of missing people due to Partition-related migration along the Punjabi border at around 2.23 million.[29]

Nisid Hajari, in Midnight's Furies (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) wrote:[36]

Gangs of killers set whole villages aflame, hacking to death men and children and the aged while carrying off young women to be raped. Some British soldiers and journalists who had witnessed the Nazi death camps claimed Partition's brutalities were worse: pregnant women had their breasts cut off and babies hacked out of their bellies; infants were found literally roasted on spits.

By the time the violence had subsided, Hindus and Sikhs had been completely wiped out of Pakistan's West Punjab and similarly Muslims were completely wiped out of India's East Punjab.[37]

Partition also affected other areas of the subcontinent besides the Punjab. Anti-Hindu riots took place in Hyderabad, Sind. On 6 January anti-Hindu riots broke out in Karachi, leading to an estimate of 1100 casualties.[38] 776,000 Sindhi Hindus fled to India.[39]

Anti-Muslim riots also rocked Delhi. According to Gyanendra Pandey's recent account of the Delhi violence between 20,000 and 25,000 Muslims in the city lost their lives.[40] Tens of thousands of Muslims were driven to refugee camps regardless of their political affiliations and numerous historic sites in Delhi such as the Purana Qila, Idgah and Nizamuddin were transformed into refugee camps. At the culmination of the tensions in Delhi 330,000 Muslims were forced to flee the city to Pakistan. The 1951 Census registered a drop of the Muslim population in Delhi from 33.22% in 1941 to 5.33% in 1951.[41]

Hyderabad

[edit]The Hyderabad massacres[42] refers to the mass killings and massacre of Hyderabadi Muslims that took place simultaneously with the Indian annexation of Hyderabad (Operation Polo). The killings were perpetrated by local Hindu fanatic militias, and by the Indian Army. The death toll of Muslims massacred in the process has been estimated to be at least 200,000.[43] Apart from mass killings, activists such as Sundarayya mention systematic torture, rapes and lootings by Indian soldiers.[44] The violence was committed by Hindu militias included the desecration of mosques, mass killings, the seizure of houses and land, looting and burning of Muslim shops, as well as the rape and abduction of Muslim women.[45][46][47]

Since 1951

[edit]The CPPCG was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 9 December 1948 and came into effect on 12 January 1951 (Resolution 260 (III)). After the necessary 20 countries became parties to the convention, it came into force as international law on 12 January 1951.[1] At that time however, only two of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council (UNSC) were parties to the treaty, which caused the convention to languish for over four decades.[48]

Zanzibar

[edit]In 1964, towards the end of the Zanzibar Revolution—which led to the overthrow of the Sultan of Zanzibar and his mainly Arab government by local African revolutionaries—John Okello claimed in radio speeches to have killed or imprisoned tens of thousands of the Sultan's "enemies and stooges",[49] but estimates of the number of deaths vary greatly, from "hundreds" to 20,000. The New York Times and other Western newspapers gave figures of 2–4,000;[50][51] the higher numbers possibly were inflated by Okello's own broadcasts and exaggerated media reports.[49][52][53] The killing of Arab prisoners and their burial in mass graves was documented by an Italian film crew, filming from a helicopter, in Africa Addio.[54] Many Arabs fled to safety in Oman[52] and by Okello's order no Europeans were harmed.[55] The violence did not spread to Pemba.[53]

These events have been described by some as an act of genocide,[56][57][58] including genocide scholar Leo Kuper.[59]

Nigeria

[edit]Biafra (1966–1970)

[edit]After Nigeria gained its independence from British rule in 1960, stigma towards the Igbo ethnic group of the east increased. When a supposedly Igbo led coup[60] overthrew and murdered senior government officials, the other ethnic groups of Nigeria, particularly the Hausa, launched a massive anti-Igbo campaign. This campaign began with the 1966 anti-Igbo pogrom and the 1966 Nigerian counter-coup. In the pogrom, Igbo property was destroyed and up to 300,000 Igbos fled the North and sought safety in the East and about 30,000 Igbos were killed. In the counter-coup that followed, Igbo civilians and military personnel were also systematically murdered.[61]

On 30 May 1967, when the Igbos declared their independence from Nigeria and formed the breakaway state of Biafra,[62] the Nigerian and British governments launched a total blockade of Biafra.[63] Initially on the offensive, Biafra began to suffer and its government frequently had to move because the Nigerian army kept on conquering its capital cities. The main cause of death was starvation, which occurred after the middle of the war.[64] Children were often afflicted with Kwashiorkor, a disease caused by malnutrition. The people resorted to cannibalism on many occasions.[65] The documentation of the suffering of the Igbo children is attributed to the work of the French Red Cross and other Christian organisations. There are many estimates for the death toll of the Igbo in the genocide. The number of soldiers who were killed in the war is estimated to be 100,000 and the number of civilians who were also killed ranges from 500,000 to 3.5 million. More than half of those who died in the war were children.[63] Historians, such as Chima Korieh and Apollos Nwauwa, have argued that the pogroms against Igbos and Nigeria's blockade of Biafra constitute acts of genocide.[66]

Currently, Nigeria still suppresses peaceful protests by Biafra independence hopefuls, often by sending soldiers to beat protestors and even to kill them.[67]

Cambodia (1975–1979)

[edit]

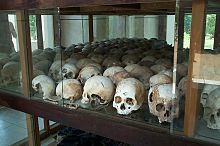

In Cambodia between 1975 and 1979, a genocide in which an estimated 1.5 to 3 million people died was committed by the Khmer Rouge (KR) regime.[68][69][70] The KR group and its leader Pol Pot overthrew Lon Nol and the Khmer Republic when it captured Phnom Penh at the end of the Cambodian Civil War on 17 April 1975, renamed Cambodia Democratic Kampuchea and attempted to transform Cambodia into an agrarian socialist society which would be governed according to the ideals of Stalinism and Maoism. The KR's policies which included the forced relocation of the Cambodian population from urban centers to rural areas, torture, mass executions, the use of forced labor, malnutrition, and disease caused the death of an estimated 25 percent of Cambodia's total population (around 2 million people).[71][72] The genocide ended following the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia.[73] Since then, at least 20,000 mass graves, known as the Killing Fields, have been uncovered.[74]

The Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot, Ta Mok and other leaders, organized the mass killing of ideologically suspect groups, ethnic minorities such as ethnic Vietnamese, Chinese (or Sino-Khmers), Chams and Thais, former civil servants, former government soldiers, Buddhist monks, secular intellectuals and professionals, and former city dwellers. Khmer Rouge cadres who were defeated in factional struggles were also liquidated in purges. Man-made famines and slave labor resulted in many hundreds of thousands of deaths.[75] Craig Etcheson suggested that the death toll was between 2 and 2.5 million, with a "most likely" figure of 2.2 million. After 5 years of researching 20,000 grave sites, he concluded that "these mass graves contain the remains of 1,386,734 victims of execution."[76] However, some scholars argued that the Khmer Rouge were not racist and they had no intention to exterminate ethnic minorities or the Cambodian people as a whole; in the view of these scholars, the Khmer Rouge's brutality was the product of an extreme version of communist ideology.[77]

On 6 June 2003, the Cambodian government and the United Nations agreed to set up the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), which would exclusively focus on the crimes which were committed by the most senior Khmer Rouge officials during the period of Khmer Rouge rule from 1975 to 1979.[78][79] The judges were sworn in during early July 2006.[80] The investigating judges were presented with the names of five possible suspects by the prosecution on 18 July 2007.[80][81]

Kang Kek Iew was formally charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity and detained by the Tribunal on 31 July 2007.[82] He was indicted on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity on 12 August 2008.[83] His appeal was rejected on 3 February 2012, and he continued serving a sentence of life imprisonment.[84] Nuon Chea, a former prime minister, was indicted on charges of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and several other crimes under Cambodian law on 15 September 2010.[78] He was transferred into the custody of the ECCC on 19 September 2007. His trial began on 27 June 2011.[85][86] On 16 November 2018, he was sentenced to a life in prison for genocide.[87] Khieu Samphan, a former head of state, was indicted on charges of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and several other crimes under Cambodian law on 15 September 2010.[78] He was transferred into the custody of the ECCC on 19 September 2007. His trial also began on 27 June 2011.[85][86] On 16 November 2018, he was sentenced to a life in prison for genocide.[87] Ieng Sary, a former foreign minister, was indicted on charges of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and several other crimes under Cambodian law on 15 September 2010.[82] He was transferred into the custody of the ECCC on 12 November 2007. His trial began on 27 June 2011.[85][86] He died in March 2013.[88] Ieng Thirith, wife of Ieng Sary and a former minister for social affairs, was indicted on charges of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and several other crimes under Cambodian law on 15 September 2010.[82] She was transferred into the custody of the ECCC on 12 November 2007. Proceedings against her have been suspended pending a health evaluation.[86][89]

Some of the international jurists and the Cambodian government disagreed over whether any other people should be tried by the Tribunal.[81]

Guatemala (1981–1983)

[edit]

During the Guatemalan civil war, between 140,000 and 200,000 people are estimated to have died and more than one million people fled their homes and hundreds of villages were destroyed. The officially chartered Historical Clarification Commission attributed more than 93% of all documented human rights violations to U.S.–supported Guatemala's military government; and estimated that Maya Indians accounted for 83% of the victims.[90] Although the war lasted from 1960 to 1996, the Historical Clarification Commission concluded that genocide might have occurred between 1981 and 1983,[91] when the government and guerrilla had the fiercest and bloodiest combats and strategies, especially in the oil-rich area of Ixcán on the northern part of Quiché.[92] The total numbers of killed or "disappeared" was estimated to be around 200,000,[93] although this is an extrapolation that was done by the Historical Clarification Commission based on the cases that they documented, and there were no more than 50,000.[94] The commission also found that U.S. corporations and government officials "exercised pressure to maintain the country's archaic and unjust socio-economic structure", and that the Central Intelligence Agency backed illegal counterinsurgency operations.[95]

In 1999, Nobel peace prize winner Rigoberta Menchú brought a case against the military leadership in a Spanish Court. Six officials, among them Efraín Ríos Montt and Óscar Humberto Mejía Victores, were formally charged on 7 July 2006 to appear in the Spanish National Court after Spain's Constitutional Court ruled in 2005 that Spanish courts could exercise universal jurisdiction over war crimes committed during the Guatemalan Civil War.[97] In May 2013, Rios Montt was found guilty of genocide for killing 1,700 indigenous Ixil Mayans during 1982–83 by a Guatemalan court and sentenced to 80 years in prison.[96] However, on 20 May 2013, the Constitutional Court of Guatemala overturned the conviction, voiding all proceedings back to 19 April and ordering that the trial be "reset" to that point, pending a dispute over the recusal of judges.[98][99] Ríos Montt's trial was supposed to resume in January 2015,[100] but it was suspended after a judge was forced to recuse herself.[101] Doctors declared Ríos Montt unfit to stand trial on 8 July 2015, noting that he would be unable to understand the charges brought against him,[102] subsequently dying in 2018. As of 2023,[update] the court cases around the Guatemalan genocide remain in limbo.[103]

Burundi in 1972 and 1993

[edit]After Burundi gained its independence in 1962, two events occurred which were labeled genocides. The first event was the mass-killing of Hutus by Burundi's Tutsi-dominated government and army in 1972[104][page needed] and the second event was the killing of Tutsis by Burundi's Hutu population in 1993.[105][106] This event and the coup attempt which triggered it also triggered the Burundian Civil War and it was recognized as an act of genocide in the final report of the International Commission of Inquiry for Burundi which was presented to the United Nations Security Council in 2002.[107]

Equatorial Guinea

[edit]Francisco Macías Nguema was the first President of Equatorial Guinea, from 1968 until his overthrow in 1979.[108] During his presidency, his country was nicknamed "the Auschwitz of Africa". Nguema's regime was characterized by its abandonment of all government functions except internal security, which was accomplished by terror; he acted as his country's chief judge and sentenced thousands of people to death. This led to the death or exile of up to 1/3 of the country's population. From a population of 300,000, an estimated 80,000 had been killed, in particular those of the Bubi ethnic minority on Bioko associated with relative wealth and education.[109] Uneasy around educated people, he had killed everyone who wore glasses.[110] All schools were ordered closed in 1975. The economy collapsed and skilled citizens and foreigners emigrated.[111]

On 3 August 1979, he was overthrown by his nephew Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo.[112] Macías Nguema was captured and tried for genocide and other crimes along with 10 others. All were found guilty, four received terms of imprisonment and Nguema and the other six were executed on 29 September.[113]

[John B. Quigley] noted at Macías Nguema's trial that Equatorial Guinea had not ratified the Genocide convention and that records of the court proceedings show that there was some confusion over whether Nguema and his co-defendants were tried under the laws of Spain (the former colonial government) or whether the trial was justified on the claim that the Genocide Convention was part of customary international law. Quigley stated, "The Macias case stands out as the most confusing of domestic genocide prosecutions from the standpoint of the applicable law. The Macias conviction is also problematic from the standpoint of the identity of the protected group."[114]

Indonesia

[edit]Indonesian mass killings of 1965–66

[edit]In the mid-1960s, hundreds of thousands of leftists and others who were tied to the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) were massacred by the Indonesian military and right-wing paramilitary groups after a failed coup attempt which was blamed on the Communists. At least 500,000 people were killed over a period of several months, and thousands of other people were interned in prisons and concentration camps under extremely inhumane conditions.[115] The violence culminated in the fall of President Sukarno and the commencement of Suharto's thirty-year authoritarian rule. Some scholars have described the killings as genocide,[116][117][page needed] including Robert Cribb, Jess Melvin and Joshua Oppenheimer.[118][119][120]

According to scholars and a 2016 international tribunal held in the Hague, Western powers, including Great Britain, Australia and the United States, aided and abetted the mass killings.[121] U.S. Embassy officials provided kill lists to the Indonesian military which contained the names of 5,000 suspected high-ranking members of the PKI.[122][123] Many of those accused of being Communists were journalists, trade union leaders and intellectuals.[124] Historian Geoffrey B. Robinson states that the context of the cold war is crucial in understanding the violence and provided a conducive environment to the perpetration.[125]

Methods of killing included beheading, evisceration, dismemberment and castration.[126] A top-secret CIA report stated that the massacres "rank as one of the worst mass murders of the 20th century, along with the Soviet purges of the 1930s, the Nazi mass murders during the Second World War, and the Maoist bloodbath of the early 1950s."[123] While there is contention in it being considered alongside genocides, Robinson states "there is no doubt that it was one of the largest and swiftest instances of mass killing and incarceration in the twentieth century, nor that it meets the legal definition of extermination."[127]

West New Guinea/West Papua

[edit]An estimated 100,000+ Papuans have died since Indonesia took control of West New Guinea from the Dutch Government in 1963.[128] An academic report published by Yale Law School alleged that "contemporary evidence set out [in this report] suggests that the Indonesian government has committed proscribed acts with the intent to destroy the West Papuans as such, in violation of the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide and the customary international law prohibition this Convention embodies."[129] Historian Geoffrey Robinson highlights Indonesian policies of assimilation forced onto West Papuans which have been described as cultural genocide.[130]

East Timor

[edit]

East Timor was invaded by Indonesia on 7 December 1975 and it remained under Indonesian occupation as an annexed territory with provincial status until it gained its independence from Indonesia in 1999.[131][132][133] A detailed statistical report which was prepared for the Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor cited a lower range of 102,800 conflict-related deaths in the period from 1974 to 1999,[134] namely, approximately 18,600 killings and 84,200 excess deaths which were caused by hunger and illness, including deaths which were caused by the Indonesian military's use of "starvation as a weapon to exterminate the East Timorese",[135][136] most of which occurred during the Indonesian occupation.[135][137] Earlier estimates of the number of people who died during the occupation ranged from 60,000 to 200,000.[138]

According to Sian Powell, a UN report confirmed that the Indonesian military used starvation as a weapon and employed Napalm and chemical weapons, which poisoned the food and water supply.[135] Ben Kiernan wrote:

the crimes committed ... in East Timor, with a toll of 150,000 in a population of 650,000, clearly meet a range of sociological definitions of genocide ... [with] both political and ethnic groups as possible victims of genocide. The victims in East Timor included not only that substantial 'part' of the Timorese 'national group' targeted for destruction because of their resistance to Indonesian annexation ... but also most members of the twenty-thousand strong ethnic Chinese minority.[139][140]

Bangladesh

[edit]Biharis

[edit]Immediately after the Bangladesh independence war of 1971, those Biharis who were still living in Bangladesh were accused of being "pro-Pakistani" "traitors" by the Bengalis, and an estimated 1,000 to 150,000 Biharis were killed by Bengali mobs in what has been described as a "Retributive Genocide".[141][142] Mukti Bahini has been accused of crimes against minority Biharis by the Government of Pakistan. According to a white paper released by the Pakistani government, the Awami League killed 30,000 Biharis and West Pakistanis. Bengali mobs were often armed, sometimes with machetes and bamboo staffs.[143] 300 Biharis were killed by Bengali mobs in Chittagong. The massacre was used by the Pakistani Army as a justification to launch Operation Searchlight against the Bengali nationalist movement.[144] Biharis were massacred in Jessore, Panchabibi and Khulna (where, in March 1972, 300 to 1,000 Biharis were killed and their bodies were thrown into a nearby river).[145][146][147] Having generated unrest among Bengalis,[148] Biharis became the target of retaliation. The Minorities at Risk project puts the number of Biharis killed during the war at 1,000;[149] however, political scientist and statitician R. J. Rummel cites a "likely" figure of 150,000.[150]

1971 war

[edit]An academic consensus holds that the events that took place during the Bangladesh Liberation War constituted genocide.[151] During the nine-month-long conflict an estimated 300,000 to 3 million people were killed and the Pakistani armed forces raped between 200,000 and 400,000 Bangladeshi women and girls in an act of genocidal rape.[152]

A 2008 study estimated that up to 269,000 civilians died in the conflict; the authors of the study noted that this estimate is far higher than two earlier estimates.[153] Although Bangladesh is an officially secular country,[154] professor of political scientist Donald Beachler argues that the events leading up to East Pakistan's secession amounted to religious and ethnic genocide.[155]

A case was filed in the Federal Court of Australia on 20 September 2006 for alleged war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide during 1971 by the Pakistani Armed Forces and its collaborators:[156]

We are glad to announce that a case has been filed in the Federal Magistrate's Court of Australia today under the Genocide Conventions Act 1949 and War Crimes Act. This is the first time in history that someone is attending a court proceeding in relation to the [alleged] crimes of Genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity during 1971 by the Pakistani Armed Forces and its collaborators. The Proceeding number is SYG 2672 of 2006. On 25 October 2006, a direction hearing will take place in the Federal Magistrates Court of Australia, Sydney registry before Federal Magistrate His Honor Nicholls.

On 21 May 2007, at the request of the applicant, the case was discontinued.[157]

Indigenous Chakmas

[edit]In Bangladesh the persecution of the indigenous tribes of the Chittagong Hill Tracts such as the Chakma, Marma, Tripura and others, who are mainly Buddhists, has been described as genocidal.[158] There are also accusations of Chakmas being forced to leave their religion, many of them children who have been abducted for this purpose. The conflict started soon after Bangladeshi independence in 1971, when the Constitution imposed Bengali as the only sole language and a military coup happened in 1975. Subsequently, the government encouraged and sponsored the massive settlement of Bangladeshis in the region,[159] which changed the indigenous population's demographics from 98 percent in 1971 to fifty percent by 2000.[160] The Bangladeshi government sent one third of its military forces to the region to support the settlers, sparking a protracted guerilla war between Hill tribes and the military.[161] During this conflict, which officially ended in 1997, and during the subsequent period, a large number of human rights violations against the indigenous peoples have been reported, with violence against indigenous women being particularly extreme.[162]

Bengali soldiers and some fundamentalist settlers were also accused of raping native Jumma (Chakma) women "with impunity", with the Bangladeshi security forces doing little or nothing to protect the Jummas and instead assisting the rapists and settlers.[163][164]

Laos

[edit]In 1975 the Pathet Lao was able to win the Laotian Civil War, they abolished the constitutional monarchy and established a Marxist–Leninist state. Many ethnic Hmong fought for the CIA-backed Secret Army against the Pathet Lao during the civil war,[165] and have fought an insurgency against the Laotian government since 1975, as a result ethnic Hmong in Laos have been subject to human rights abuses and persecution.[166][167][168] Some have labelled this persecution as genocide.[169][170] Vang Pobzeb of the Lao Human Rights Council estimated that 300,000 Hmong and Lao people have been killed by the Vietnamese and Laotian governments between 1975 and 2002, claiming that the Laotian government engaged in ethnic cleansing and genocide.[171]

Argentina

[edit]

In September 2006, Miguel Osvaldo Etchecolatz, who had been the police commissioner of the province of Buenos Aires during the Dirty War (1976–1983), was found guilty of six counts of murder, six counts of unlawful imprisonment and seven counts of torture in a federal court. The judge who presided over the case, Carlos Rozanski, described the offences as part of a systematic attack that was intended to destroy parts of society that the victims represented and as such was genocide. Rozanski noted that CPPCG does not include the elimination of political groups (because that group was removed at the behest of Stalin),[172] but instead based his findings on 11 December 1946 United Nations General Assembly Resolution 96 barring acts of genocide "when racial, religious, political and other groups have been destroyed, entirely or in part" (which passed unanimously), because he considered the original UN definition to be more legitimate than the politically compromised CPPCG definition.[173]

Ethiopia

[edit]Mengistu regime

[edit]Ethiopia's former Soviet-backed Marxist dictator Mengistu Haile Mariam was tried in an Ethiopian court, in absentia, for his role in mass killings. Mengistu's charge sheet and evidence list covered 8,000 pages. The evidence against him included signed execution orders, videos of torture sessions, and personal testimonies.[174] The trial began in 1994 and on 12 December 2006 Mengistu was found guilty of genocide and other offences. He was sentenced to life in prison in January 2007.[175][176] Ethiopian law includes attempts to annihilate political groups in its definition of genocide.[177] Including Mengistu, 55 Derg officials were found guilty of genocide during the trials.[178] Several former Derg members have been sentenced to death.[179] Zimbabwe refused to respond to Ethiopia's extradition request for Mengistu, which permitted him to avoid a life sentence. Mengistu supported Robert Mugabe, the former long-standing President of Zimbabwe, during his leadership of Ethiopia.[180]

Michael Clough, a US attorney and a longtime Ethiopia observer, told Voice of America in a statement released on 13 December 2006,[181]

The biggest problem with prosecuting Mengistu for genocide is that his actions did not necessarily target a particular group. They were directed against anybody who was opposing his government, and they were generally much more political than based on any ethnic targeting. In contrast, the irony is the Ethiopian government itself has been accused of genocide based on atrocities committed in Gambella. I'm not sure that they qualify as genocide either. But in Gambella, the incidents, which were well documented in a human rights report of about 2 years ago, were clearly directed at a particular group, the tribal group, the Anuak.

An estimated 150,000 university students, intellectuals, and politicians were killed during Mengistu's rule.[182] Amnesty International estimates that up to 500,000 people were killed during the Ethiopian Red Terror[183] Human Rights Watch described the Red Terror as "one of the most systematic uses of mass murder by a state ever witnessed in Africa".[174] During his reign it was not uncommon to see students, suspected government critics or rebel sympathisers hanging from lampposts. Mengistu himself is alleged to have murdered opponents by garroting or shooting them, saying that he was leading by example.[184]

Amhara genocide

[edit]Since the 1990s, the Amhara people of Ethiopia have been subject to ethnic violence, including massacres by Tigrayan, Oromo and Gumuz ethnic groups among others, which some have characterized as a genocide.[185][186][187]

Uganda

[edit]Idi Amin's regime

[edit]After Idi Amin Dada overthrew the regime of Milton Obote in 1971, he declared that the Acholi and Lango tribes were his enemies, because Obote was a Lango and Amin saw their domination of the army as a threat to his rule.[188] In January 1972, Amin issued an order to the Ugandan army which commanded it to assemble and kill all Acholi and Lango soldiers, and then, he ordered the Ugandan army to round up all Acholi and Lango soldiers and confine them within army barracks, there, they were either slaughtered by the Ugandan army or they were killed when the Ugandan air force bombed the barracks.[188]

In August of that same year, Amin ordered the mass expulsion of the Indian community.[189][190] Amin declared God had spoken to him in a dream and told him not only to expel all Indian residents, but also to take revenge on the United Kingdom. Indian-Ugandans were given 90 days to leave the country, with many willingly doing so in fearing the same fate as the Acholi and Lango peoples months before. During this time, Ugandan soldiers engaged in theft and physical and sexual assault against Indians in the country.[191][better source needed] Amin cloaked the actions in black nationalist rhetoric, portraying the acts as necessary for transferring economic control into the hands of black Ugandans.[192] Indian refugees were largely accepted by the governments of the United Kingdom, Canada, and India, with smaller numbers going to different countries. By 1979, the Indian community of Uganda was rumoured to be no more than 50 people, and there is no longer any identifiable "Indian-Ugandan" community anywhere in the world.[193]

Bush War (1981–1985)

[edit]The genocide under Amin would later lead to reprisals by Milton Obote's regime during the Ugandan Bush War, resulting in widespread human rights abuses which primarily targeted the Baganda people.[188] These abuses included the forced removal of 750,000 civilians from the area of the then Luweero District, including present-day Kiboga, Kyankwanzi, Nakaseke, and others. They were moved into refugee camps controlled by the military. Many civilians outside the camps, in what came to be known as the "Luweero triangle", were continuously abused as "guerrilla sympathizers". The International Committee of the Red Cross has estimated that by July 1985, the Obote regime had been responsible for more than 300,000 civilian deaths across Uganda.[194][195]

Ba'athist Iraq

[edit]The regime of Saddam Hussein has been accused of committing multiple mass killings and genocides. According to Human Rights Watch, 290,000 Iraqis were killed or disappeared by Saddam's regime:

The estimate of 290,000 "disappeared" and presumed killed includes the following: more than 100,000 Kurds killed during the 1987-88 Anfal campaign and lead-up to it; between 50,000 and 70,000 Shi`a arrested in the 1980s and held indefinitely without charge, who remain unaccounted for today; an estimated 8,000 males of the Barzani clan removed from resettlement camps in Iraqi Kurdistan in 1983; 10,000 or more males separated from Feyli Kurdish families and deported to Iran in the 1980s; an estimated 50,000 opposition activists, including Communists and other leftists, Kurds and other minorities, and out-of-favor Ba`thists, arrested and "disappeared" in the 1980s and 1990s; some 30,000 Iraqi Shi`a men rounded up after the abortive March 1991 uprising and not heard from since; hundreds of Shi`a clerics and their students arrested and "disappeared" after 1991; several thousand marsh Arabs who disappeared after being taken into custody during military operations in the southern marshlands; and those executed in detention-in some years several thousand-in so-called "prison cleansing" campaigns.[196]

Genocide of Kurds

[edit]On 23 December 2005, a Dutch court delivered its ruling in a case which was brought against Frans van Anraat, who had previously supplied chemicals to Iraq. The court ruled that "[it] thinks and considers it legally and convincingly proven that the Kurdish population meets the requirement under the genocide convention as an ethnic group. The court has no other conclusion than that these attacks were committed with the intent to destroy the Kurdish population of Iraq." Because van Anraat supplied the chemicals before 16 March 1988, the date of the Halabja poison gas attack he was guilty of a war crime but he was not guilty of complicity in genocide.[197][198]

Ahwaris

[edit]In the 1990s, the Mesopotamian Marshes of Iraq were drained for political motives, namely to force the Ahwaris out of the area and to punish them for their role in the 1991 uprising against Saddam Hussein's government.[199] However, the government's stated reasoning was to reclaim land for agriculture and exterminate breeding grounds for mosquitoes.[200] The displacement of more than 200,000 of the Ahwaris, and the associated state-sponsored campaign of violence against them, has led the United States and others to describe the draining of the marshes as ecocide, ethnic cleansing,[201][202] or genocide.[203]

People's Republic of China

[edit]Tibet

[edit]On 5 June 1959, Shri Purshottam Trikamdas, Senior Advocate, Supreme Court of India, presented a report on Tibet to the International Commission of Jurists (an NGO). The press conference address on the report states in paragraph 26:

From the facts stated above the following conclusions may be drawn: ... (e) To examine all such evidence obtained by this Committee and from other sources and to take appropriate action thereon and in particular to determine whether the crime of Genocide—for which already there is strong presumption—is established and, in that case, to initiate such action as envisaged by the Genocide Convention of 1948 and by the Charter of the United Nations for suppression of these acts and appropriate redress;[204]

The report by the International Commission of Jurists (1960) claimed that there was only a "cultural" genocide. ICJ Report (1960) page 346: "The committee found that acts of genocide had been committed in Tibet in an attempt to destroy the Tibetans as a religious group, and its report also stated that independent of any conventional obligation, such acts are acts of genocide. The committee did not find that there was sufficient proof of the destruction of Tibetans as a race, nation or ethnic group as such by methods that can be regarded as genocide in international law."

However, the use of the term cultural genocide is contested by academics such as Barry Sautman.[205] Tibetan is the everyday language of the Tibetan people.[206]

The Central Tibetan Administration and other Tibetans who work in the exile media have claimed that approximately 1.2 million Tibetans have died of starvation, violence, or other indirect causes since 1950.[207] White states that "In all, over one million Tibetans, a fifth of Tibet's total population, had died as a result of the Chinese occupation right up until the end of the Cultural Revolution."[208] This figure has been refuted by Patrick French, the former Director of the Free Tibet Campaign in London.[209]

Jones argued that the struggle sessions which were held after the crushing of the 1959 Tibetan uprising may be considered acts of genocide, based on the claim that the conflict resulted in 92,000 deaths.[210] However, according to tibetologist Tom Grunfeld, "the veracity of such a claim is difficult to verify."[211]

Paraguay

[edit]Between 1956 and 1989, while Paraguay was under the military rule of General Alfredo Stroessner, the indigenous population of Paraguay lost more of its territory through confiscations than it ever lost during any other period in Paraguay's history and it was also subjected to systematic human rights abuses. In 1971, Mark Münzel, a German anthropologist, accused Stroessner of attempting to commit a genocide against the indigenous peoples of Paraguay[212] and Bartomeu Melià, a Jesuit anthropologist stated that the forced relocations of the indigenous peoples was an ethnocide.[213] In the early 1970s, the Stroessner regime was charged with being complicit in genocide by international human rights groups. However, because of the repressive actions which were undertaken against them by the state, the indigenous tribes politically organized themselves and as a result, they played a major role in bringing about the end of the military dictatorship and they also played a major role in Paraguay's eventual transition to democracy.[214][213][215]

The Aché of Eastern Paraguay were hardest-hit by the Stroessner regime's policies. Under Stroessner, the Paraguayan government promoted the exploitation of Aché territory for its natural resources by multinational corporations. During the 1960s and 1970s, 85 percent of the Aché tribe died, many of the Aché were hacked to death with machetes so room could be made for the timber industry, mining, farming and ranchers.[216] One estimate posits this amounts to 900 deaths.[217]

Brazil

[edit]The Helmet massacre of the Tikuna people which occurred in 1988 was initially labeled a homicide. During the massacre four people died, nineteen were wounded, and ten disappeared. Since 1994, Brazilian courts have labeled the episode a genocide.[218] Thirteen men were convicted of genocide in 2001. In November 2004, after an appeal was filed before Brazil's federal court, the man initially found guilty of hiring men to carry out the genocide was acquitted, and the killers had their initial sentences of 15–25 years reduced to 12 years.[219]"

In November 2005, during an investigation which was code-named Operation Rio Pardo, Mario Lucio Avelar, a Brazilian public prosecutor in Cuiabá, told Survival International that he believed that there were sufficient grounds to prosecute the perpetrators of the genocide of the Rio Pardo Indians. In November 2006 twenty-nine people were arrested and others were implicated, such as a former police commander and the governor of Mato Grosso state.[220]

In 2006 the Brazilian Supreme Federal Court unanimously reaffirmed its ruling that the crime which is known as the Haximu massacre (perpetrated against the Yanomami people in 1993)[221] was a genocide and ruled that the decision of a federal court to sentence miners to 19 years in prison for genocide in connection with other offenses, such as smuggling and illegal mining, was valid.[221][222]

Zimbabwe

[edit]The Gukurahundi was a series of massacres of Ndebele civilians which were carried out by the Zimbabwe National Army from early 1983 to late 1987. Its name is derived from a Shona language term which reads "the early rain which washes away the chaff before the spring rains" when it is loosely translated into English.[223] During the Rhodesian Bush War two rival nationalist parties, Robert Mugabe's Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) and Joshua Nkomo's Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU), had emerged in order to challenge Rhodesia's predominantly white government.[224] ZANU initially defined Gukurahundi as an ideological strategy which was aimed at carrying the war into major settlements and individual homesteads.[225] Following Mugabe's ascension to power, his government remained threatened by "dissidents"—disgruntled former guerrillas and supporters of ZAPU.[226] ZANU mainly recruited from the majority Shona people, whereas ZAPU received its greatest amount of support among the minority Ndebele. In early 1983, the North Korean-trained Fifth Brigade, an infantry brigade of the Zimbabwe National Army (ZNA), launched a crackdown against dissidents in Matabeleland North Province, a homeland of the Ndebele. Over the following two years, thousands of Ndebele were either detained by government forces and marched to re-education camps or they were summarily executed. Although there are different estimates, the consensus of the International Association of Genocide Scholars (IAGS) is that more than 20,000 people were killed. The IAGS has classified the massacres as a genocide.[227]

Lebanon

[edit]The Sabra and Shatila massacre occurred from 16–18 September 1982, where between 1,300 and 3,500 civilians—mostly Palestinians and Lebanese Shias—were killed, in the city of Beirut during the Lebanese Civil War.[228] It was perpetrated by the Lebanese Forces, one of the main Christian militias in Lebanon, and supported by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) that had surrounded Beirut's Sabra neighbourhood and the adjacent Shatila refugee camp.[229] On 16 December 1982, the United Nations General Assembly condemned the Sabra and Shatila massacre and declared it to be an act of genocide.[230][231][232] In February 1983, an independent commission chaired by Irish diplomat Seán MacBride, assistant to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, concluded that the IDF, as the then occupying power over Sabra and Shatila, bore responsibility for the militia's massacre.[233] The commission also stated that the massacre was a form of genocide.[234]

Afghanistan

[edit]Genocide of Afghans by Soviet Armed Forces and proxies

[edit]

Numerous scholars and academics have stated that the Soviet military perpetrated a genocidal campaign of extermination against Afghan people during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.[235][236] Afghan president Mohammed Daoud Khan was deposed and murdered in 1978's Saur Revolution by the Khalqist faction of People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), who subsequently established their own government, the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan.[237]

What followed the April coup of 1978 was severe repression of a kind previously unknown in Afghanistan. American journalist and CNAS member Robert D. Kaplan argued that, while Afghanistan had been "poor" and "underdeveloped", it was a "relatively civilized" country that "had never known very much political repression" until 1978.[238] Political scientist Barnett Rubin wrote, "Khalq used mass arrests, torture, and secret executions on a scale Afghanistan had not seen since the time of Abdul Rahman Khan, and probably not even then".[239] After gaining power, the Khalqists unleashed a campaign of "red terror", killing more than 27,000 people in the Pul-e-Charkhi prison, prior to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979.[238]

After Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, deposing and killing Hafizullah Amin in Operation Storm-333 and installing Babrak Karmal as General Secretary, the brutality of communists intensified. The army of the Soviet Union killed large numbers of Afghans, attempting to suppress resistance from the Afghan mujahideen.[240] Numerous mass murders were perpetrated by the Soviet Army during the summer of 1980. Soviet forces also launched chemical attacks against civilian populations.[241] During the 1980s, the communist PDPA regime also killed and tortured thousands of individuals in the Pul-e-Charkhi prison.[242]

One notorious atrocity was the Laghman massacre in April 1985 in the villages of Kas-Aziz-Khan, Charbagh, Bala Bagh, Sabzabad, Mamdrawer, Haider Khan and Pul-i-Joghi[243] in the Laghman Province. At least 500 civilians were killed.[244] In the Kulchabat, Bala Karz and Mushkizi massacre which was committed on 12 October 1983, the Red Army gathered 360 people at the village square and shot them, including 20 girls and over a dozen older people.[245][246][247] The Rauzdi massacre and Padkhwab-e Shana massacre were also documented.[248] Approximately 2 million Afghan civilians were killed by the Soviet military and its proxies during the Soviet invasion and occupation.[249]

Soviet Air Forces perpetrated scorched-earth strategy during its bombing campaigns, which consisted of carpet bombing of cities and indiscriminate attacks that destroyed entire villages. Millions of land-mines (often camouflaged as kids' playthings) were planted by Soviet military across Afghanistan. Around 90% of Kandahar's inhabitants were forcibly expelled, as a result of Soviet atrocities during the war.[250] Everything was the target in the country, from cities, villages, up to schools, hospitals, roads, bridges, factories and orchards. Soviet tactics included targeting areas which showed support for the Afghan resistance, and forcing the populace to flee the rural regions where the communists had no territorial control. Half of Afghanistan's 24,000 villages and most of the rural facilities were destroyed by the end of the war.[251][252] During the Soviet invasion and occupation between 1979 and 1992, more than 20% of the Afghan population were focibly displaced as refugees.[252][253]

Historians, academics and scholars have widely described the Soviet military campaign in Afghanistan as a genocide. These include American professor Samuel Totten,[254] Australian professor Paul R. Bartrop,[254] political scientist Anthony James Joyce,[255] scholars from Yale Law School including W. Michael Reisman and Charles Norchi,[256] writer and journalist Rosanne Klass,[257] Canadian professor Adam Jones[258] and historian Mohammed Kakar.[259] American anthropologist Louis Dupree stated that Afghans were victims of "migratory genocide" implemented by Soviet military.[250]

Massacres of Hazaras and other groups by the Taliban

[edit]Between 1996 and 2001, 15 massacres were committed by the Taliban and Al-Qaeda; the United Nations stated: "These are the same types of war crimes as those which were committed in Bosnia and they should be prosecuted in international courts"[260] Following the 1997 massacre of 3,000 Taliban prisoners by Abdul Malik Pahlawan in Mazar-i-Sharif[261] (which the Hazaras did not commit[262]) thousands of Hazara men and boys were massacred by other Taliban members in the same city in August 1998.[263] After the attack, Mullah Niazi, the commander of the attackers and the new governor of Mazar, made the following declaration when he made separate speeches at several mosques in the city:

Last year you rebelled against us and killed us. From all your homes you shot at us. Now we are here to deal with you. ...

Hazaras are not Muslim, they are Shia. They are kofr (infidels). The Hazaras killed our force here, and now we have to kill Hazaras. ...

If you do not show your loyalty, we will burn your houses, and we will kill you. You either accept to be Muslims or leave Afghanistan. ...

[W]herever you [Hazaras] go we will catch you. If you go up, we will pull you down by your feet; if you hide below, we will pull you up by your hair. ...

If anyone is hiding Hazaras in his house he too will be taken away. What [Hizb-i] Wahdat and the Hazaras did to the Talibs, we did worse ... as many as they killed, we killed more.[264]

In these killings 2,000[265][262] to 5,000,[262] or perhaps up to 20,000[266] Hazara were systematically executed across the city.[262][266] Niamatullah Ibrahimi described the killings as "an act of genocide at full ferocity".[267] The Taliban searched for combat age males by conducting door to door searches of Hazara households,[262] shooting them and slitting their throats right in front of their families.[262] Human rights organizations reported that the dead were lying on the streets for weeks before the Taliban allowed their burial due to stench and fear of epidemics. There were also reports of Hazara women being abducted and kept as sex slaves.[265] The Hazara claim the Taliban executed 15,000 of their people in their campaign through northern and central Afghanistan.;[268] the United Nation investigated three mass graves allegedly containing the victims in 2002.[268] The persecution of Hazaras has been called genocide by media outlets.[269]

Bosnia and Herzegovina

[edit]

In July 1995 Bosnian Serb forces killed more than 8,000[270][271] Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims), mainly men and boys, both in and around the town of Srebrenica during the Bosnian War. The killing was perpetrated by units of the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) which were under the command of General Ratko Mladić. The Secretary-General of the United Nations described the mass murder as the worst crime on European soil since the Second World War.[272][273] A paramilitary unit from Serbia known as the Scorpions, officially a part of the Serbian Interior Ministry until 1991, participated in the massacre,[274][275] along with several hundred Russian and Greek volunteers.[276]

In 2001 the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) delivered its first conviction for the crime of genocide, against General Krstić for his role in the 1995 Srebrenica massacre (on appeal he was found not guilty of genocide but was instead found guilty of aiding and abetting genocide).[277]

In February 2007 the International Court of Justice (ICJ) returned a judgement in the Bosnian Genocide Case. It upheld the ICTY's findings that genocide had been committed in and around Srebrenica but did not find that genocide had been committed on the wider territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina during the war. The ICJ also ruled that Serbia was not responsible for the genocide nor was it responsible for "aiding and abetting it", although it ruled that Serbia could have done more to prevent the genocide and Serbia failed to punish the perpetrators of it.[278] Before this ruling the term Bosnian Genocide had been used by some academics[279] and human rights officials.[280]

In 2010, Vujadin Popović, Lieutenant Colonel and the Chief of Security of the Drina Corps of the Bosnian Serb Army, and Ljubiša Beara, Colonel and Chief of Security of the same army, were convicted of genocide, extermination, murder and persecution by the ICTY for their role in the Srebrenica massacre and were each sentenced to life in prison.[281] In 2016 and 2017, Radovan Karadžić[282] and Ratko Mladić were sentenced for genocide.[283]

German courts handed down convictions for genocide during the Bosnian War. Novislav Djajic was indicted for his participation in the genocide, but the Higher Regional Court failed to find that there was sufficient certainty for a criminal conviction for genocide. Nevertheless, Djajic was found guilty of 14 counts of murder and one count of attempted murder.[284] At Djajic's appeal on 23 May 1997, the Bavarian Appeals Chamber found that acts of genocide were committed in June 1992, confined within the administrative district of Foca.[285] The Oberlandesgericht (higher regional court) of Düsseldorf, in September 1997, handed down a genocide conviction against Nikola Jorgic, a Bosnian Serb from the Doboj region who was the leader of a paramilitary group located in the Doboj region.[286] He was sentenced to four terms of life imprisonment for his involvement in genocidal actions that took place in regions of Bosnia and Herzegovina, other than Srebrenica;[287] and "On 29 November 1999, the Higher Regional Court (Oberlandesgericht) of Düsseldorf condemned Maksim Sokolović to 9 years in prison for aiding and abetting the crime of genocide and for grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions."[288]

Rwanda

[edit]Tutsis

[edit]

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) is a court under the auspices of the United Nations for the prosecution of offences[289] which were committed in Rwanda during the genocide which occurred there during April and July 1994, commencing on 6 April and coinciding with the end of the Rwandan Civil War.[290] The ICTR was created by the UN Security Council on 8 November 1994 in order to resolve claims which were made in Rwanda, and claims which were made by Rwandan citizens who were living in nearby states, between 1 January and 31 December 1994. For approximately 100 days from the assassination of President Juvénal Habyarimana on 6 April through mid-July, at least 800,000 people were killed, according to a Human Rights Watch estimate.[291]

As of mid-2011, the ICTR had convicted 57 people and acquitted 8 others. Another ten persons were still on trial and one is still awaiting trial. Nine other persons remain at large.[292] The first trial, of Jean-Paul Akayesu, ended in 1998 with his conviction for genocide and crimes against humanity.[293] This was the world's first conviction for genocide, as defined by the 1948 Convention. Jean Kambanda, interim Prime Minister during the genocide, pleaded guilty.[294]

Hutus

[edit]In 2010 a report accused Rwanda's Tutsi-led army of committing genocide against ethnic Hutus. The report accused the Rwandan Army and allied Congolese rebels of killing tens of thousands of ethnic Hutu refugees from Rwanda and locals in systematic attacks which were committed between 1996 and 1997. The government of Rwanda rejected the accusation.[295][296]

Somalia

[edit]1988–1991 Isaaq genocide

[edit]The Isaaq genocide or "(Sometimes referred to as the Hargeisa Holocaust)"[297][298] was the systematic, state-sponsored massacre of Isaaq civilians between 1988 and 1991 by the Somali Democratic Republic under the dictatorship of Siad Barre.[299] A number of genocide scholars (including Israel Charny,[300] Gregory Stanton,[301] Deborah Mayersen,[302] and Adam Jones[303]) as well as international media outlets, such as The Guardian,[304] The Washington Post[305] and Al Jazeera[306] among others, have referred to the case as one of genocide. In 2001, the United Nations commissioned an investigation on past human rights violations in Somalia,[299] specifically to find out if "crimes of international jurisdiction (i.e. war crimes, crimes against humanity or genocide) had been perpetrated during the country's civil war." The investigation was jointly commissioned by the United Nations Co-ordination Unit (UNCU) and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. The investigation concluded with a report which confirmed that the crime of genocide had taken place against the Isaaqs in Somalia.[299]

Peru

[edit]Alberto Fujimori's Plan Verde included a campaign to forcibly sterilize vulnerable groups through the Programa Nacional de Población (PNSRPF), a campaign that has been variably described as an ethnic cleansing or a genocidal operation.[307][308][309][310] According to Back and Zavala, the plan was an example of ethnic cleansing as it targeted indigenous and rural women.[307] Jocelyn E. Getgen of Cornell University wrote that the systemic nature of sterilizations and the mens rea of officials who drafted the plan proved an act of genocide.[308] The Centro Amazónico de Antropología y Aplicación Práctica non-profit stated that the act "was the largest genocide since [Peru's] colonization".[310] At least 300,000 Peruvians were victims of forced sterilization in the 1990s, with the majority being affected by the PNSRPF.[311]

See also

[edit]- Accusation in a mirror

- Anti-communist mass killings

- Anti-Mongolianism

- Black genocide in the United States – the notion that African Americans have been subjected to genocide throughout their history because of racism against African Americans, an aspect of racism in the United States

- Crimes against humanity

- Criticism of communist party rule

- Democide

- Ethnic cleansing

- Ethnic conflict

- Ethnic violence

- Ethnocentrism

- Ethnocide

- Far-left politics

- Far-right politics

- Far-right subcultures

- Genocide denial

- Genocide recognition politics

- Genocide of Christians by the Islamic State

- Genocide of Yazidis by the Islamic State

- Hate crime

- List of ethnic cleansing campaigns

- List of genocides

- Mass killings under communist regimes

- Nativism (politics)

- Persecution of Shias by the Islamic State

- Political cleansing of population – an aspect of political violence

- Population transfer

- Racism

- Religious intolerance

- Religious discrimination

- Religious persecution

- Religious violence

- Sectarian violence

- Supremacism

- Terrorism

- War crime

- Xenophobia

Notes

[edit]- ^ Defined under the Genocide Convention as a "national, ethnical, racial, or religious group."

- ^ By 1951, Lemkin was saying that the Soviet Union was the only state that could be indicted for genocide; his concept of genocide, as it was outlined in Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, covered Stalinist deportations as genocide by default, and differed from the adopted Genocide Convention in many ways. From a 21st-century perspective, its coverage was very broad, and as a result, it would classify any gross human rights violation as a genocide, and many events that were deemed genocidal by Lemkin did not amount to genocide. As the Cold War began, this change was the result of Lemkin's turn to anti-communism in an attempt to convince the United States to ratify the Genocide Convention.[11]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 12 January 1951. Archived from the original on 11 December 2005. Note: "ethnical", although unusual, is found in several dictionaries.

- ^ Towner 2011, pp. 625–638; Lang 2005, pp. 5–17: "On any ranking of crimes or atrocities, it would be difficult to name an act or event regarded as more heinous. Genocide arguably appears now as the most serious offense in humanity's lengthy—and, we recognize, still growing—list of moral or legal violations."; Gerlach 2010, p. 6: "Genocide is an action-oriented model designed for moral condemnation, prevention, intervention or punishment. In other words, genocide is a normative, action-oriented concept made for the political struggle, but in order to be operational it leads to simplification, with a focus on government policies."; Hollander 2012, pp. 149–189: "... genocide has become the yardstick, the gold standard for identifying and measuring political evil in our times. The label 'genocide' confers moral distinction on its victims and indisputable condemnation on its perpetrators."

- ^ Schabas, William A. (2000). Genocide in International Law: The Crimes of Crimes (PDF) (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 9, 92, 227. ISBN 0-521-78262-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2024.

- ^ Straus, Scott (2022). Graziosi, Andrea; Sysyn, Frank E. (eds.). Genocide: The Power and Problems of a Concept. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 223, 240. ISBN 978-0-2280-0951-1.

- ^ Rugira, Lonzen (20 April 2022). "Why Genocide is "the crime of crimes"". Pan African Review. Archived from the original on 13 June 2024. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ a b Anderton, Charles H.; Brauer, Jurgen, eds. (2016). Economic Aspects of Genocides, Other Mass Atrocities, and Their Prevention. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-937829-6.

- ^ Kakar, Mohammed Hassan (1995). Afghanistan: The Soviet Invasion and the Afghan Response, 1979–1982. University of California Press. pp. 213–214. ISBN 978-0-5209-1914-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ Chalk & Jonassohn 1990.

- ^ Staub 1989, p. 8.

- ^ Gellately & Kiernan 2003, p. 267.

- ^ Weiss-Wendt 2005.

- ^ Schabas 2009, p. 160: "Rigorous examination of the travaux fails to confirm a popular impression in the literature that the opposition to the inclusion of political genocide was some Soviet machination. The Soviet views were also shared by a number of other States for whom it is difficult to establish any geographic or social common denominator: Lebanon, Sweden, Brazil, Peru, Venezuela, the Philippines, the Dominican Republic, Iran, Egypt, Belgium, and Uruguay. The exclusion of political groups was originally promoted by a non-governmental organization, the World Jewish Congress, and it corresponded to Raphael Lemkin's vision of the nature of the crime of genocide."

- ^ a b Weber, Jürgen (2004). Germany, 1945–1990: A Parallel History. Central European University Press. p. 2. ISBN 963-9241-70-9.

- ^ a b Kacowicz, Arie Marcelo; Lutomski, Pawel (2007). Population resettlement in international conflicts: a comparative study. Lexington Books. p. 100. ISBN 978-0739116074.

largest movement of European people in modern history

- ^ Schuck, Peter H.; Münz, Rainer (1997). Paths to Inclusion: The Integration of Migrants in the United States and Germany. Berghahn Books. p. 156. ISBN 1-57181-092-7.

- ^ a b "Agreements of the Berlin (Potsdam) Conference, 17 July – 2 August 1945". PBS. Archived from the original on 31 October 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ Murray, Alan V. (15 May 2017). The North-Eastern Frontiers of Medieval Europe: The Expansion of Latin Christendom in the Baltic Lands. Taylor & Francis. pp. 23–. ISBN 978-1-351-88483-9.

- ^ Berend, Nora (15 May 2017). The Expansion of Central Europe in the Middle Ages. Taylor & Francis. pp. 194–. ISBN 978-1-351-89008-3.

- ^ Best, Ulrich (2008). Transgression as a Rule: German–Polish cross-border cooperation, border discourse and EU-enlargement. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 58. ISBN 978-3825806545.

- ^

- Kenety, Brian (14 April 2005). "Memories of World War II in the Czech Lands: The Expulsion of Sudeten Germans". Radio Prahs. Archived from the original on 10 June 2023. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- Prauser, Steffen; Rees, Arfon. The Expulsion of 'German' Communities from Eastern Europe at the end of the Second World War (PDF) (Report). European University Institute, Florence. p. 47. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2009. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- Phillips, Ann L. (2000). Power and influence after the Cold War: Germany in East-Central Europe. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 86. ISBN 0-8476-9523-9. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- Eberhardt, Piotr; Owsinski, Jan (2003). Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-century Central-Eastern Europe: History, Data, Analysis. M.E. Sharpe. p. 456. ISBN 0-7656-0665-8.

- ^ Frank 2008, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Fritsch-Bournazel, Renata (1992). Europe and German unification. Berg Publishers. p. 77.

- ^

- Osmańczyk, Edmund Jan (2003). Encyclopedia of the United Nations and international agreements. Routledge. p. 656. ISBN 978-0-415-93924-9. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021.

- Naimark, Norman M. (2001). Fires of hatred: ethnic cleansing in twentieth-century Europe. Harvard University Press. pp. 15, 112. 121, 136. ISBN 978-0-674-00994-3.

- Curp, T. David (2006). A clean sweep?: the politics of ethnic cleansing in western Poland, 1945–1960. University of Rochester Press. p. 200. ISBN 978-1-58046-238-9.

- Cordell, Karl (1999). Ethnicity and democratisation in the new Europe. Routledge. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-415-17312-4.

- Diner, Dan; Gross, Raphael; Weiss, Yfaat (2006). Jüdische Geschichte als allgemeine Geschichte [Jewish history as general history] (in German). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 163. ISBN 978-3-525-36288-4.

- Gibney, Matthew J. (2005). Immigration and asylum: from 1900 to the present. Vol. 3. ABC-CLIO. p. 196. ISBN 978-1-57607-796-2.

- ^

- Glassheim, Eagle (2001). Ther, Philipp; Siljak, Ana (eds.). Redrawing nations: ethnic cleansing in East-Central Europe, 1944–1948. Harvard Cold War studies book series. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-7425-1094-4.

- Shaw, Martin (2007). What is genocide?. Polity. pp. 56, 60–61. ISBN 978-0-7456-3182-0.

- Totten, Samuel; Bartrop, Paul R.; Jacobs, Steven L. (2008). Dictionary of genocide. Vol. 2. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-34644-6.

- Frank 2008, p. 5

- Rubinstein 2004, p. 260

- ^ European Court of Human Rights – Jorgic v. Germany Judgment, 12 July 2007. § 47 Archived 15 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jescheck, Hans-Heinrich (1995). Encyclopedia of Public International Law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-14280-0.

- ^ Ermacora, Felix (1991). "Gutachten Ermacora 1991" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2011.

- ^ Khan, Yasmin (2008). The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300143331.

- ^ a b c d Bharadwaj, Prasant; Khwaja, Asim; Mian, Atif (30 August 2008). "The Big March: Migratory Flows after the Partition of India" (PDF). Economic & Political Weekly: 43. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ Sethi, Najam (25 December 2015). "A heritage all but erased". The Friday Times. Archived from the original on 24 April 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ Brass 2003, pp. 78–81.

- ^ Brass 2003, p. 72.

- ^ Visweswaran, Kamala (2011). Perspectives on Modern South Asia: A Reader in Culture, History, and Representation. John Wiley & Sons. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-4051-0062-5. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ Menon, Ritu; Bhasin, Kamla (1998). Borders & Boundaries: Women in India's Partition. Rutgers University Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-8135-2552-5. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ Bates, Crispin (3 March 2011). "The Hidden Story of Partition and its Legacies". BBC. Archived from the original on 29 March 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ^ Dalrymple, William (29 June 2015). "The Great Divide". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ Brass 2003, p. 78.

- ^ Bhavnani, Nandita (2014). The Making of Exile: Sindhi Hindus and the Partition of India. Westland. ISBN 978-93-84030-33-9.

- ^ Markovits, Claude (2000). The Global World of Indian Merchants, 1750–1947. Cambridge University Press. p. 278. ISBN 978-0-521-62285-1.

- ^ Zamindar, Vazira Fazila-Yacoobali (2010). The Long Partition and the Making of Modern South Asia: Refugees, Boundaries, Histories. Columbia University Press. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-231-13847-5.

- ^ Sharma, Bulbul (2013). Muslims In Indian Cities. HarperCollins Publishers India. ISBN 978-93-5029-555-7.

- ^ Purushotham, Sunil (19 January 2021). From Raj to Republic: Sovereignty, Violence, and Democracy in India. Stanford University Press. p. 330. ISBN 978-1-5036-1455-0.

- ^ Noorani, A. G. (3–16 March 2001). "Of a massacre untold". The Hindu. Frontline. Vol. 18, no. 5. Archived from the original on 30 May 2023. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

The lowest estimates, even those offered privately by apologists of the military government, came to at least ten times the number of murders with which previously the Razakars were officially accused...

- ^ Sundarayya, Puccalapalli (1972). Telangana People's Struggle and Its Lessons. Foundation Books. ISBN 9788175963160.

- ^ Gulbargavi, Talha Hussain (17 September 2022). "1948 Hyderabad Massacre: A Timeline". The Cognate. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ "The first genocide of Muslims in independent India is celebrated each year on September 17". Muslim Mirror. 18 September 2022. Archived from the original on 7 December 2023. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ Thomson, Mike (24 September 2013). "Hyderabad 1948: India's hidden massacre". BBC News. Archived from the original on 28 August 2024.

- ^ Korey, William (March 1997). "The United States and the Genocide Convention: Leading Advocate and Leading Obstacle". Ethics & International Affairs. 11: 271–290. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7093.1997.tb00032.x. S2CID 145335690.

- ^ a b Parsons, Timothy (2003). The 1964 Army Mutinies and the Making of Modern East Africa. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-325-07068-1.

- ^ Conley, Robert (19 January 1964). "Nationalism Is Viewed as Camouflage for Reds". The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ^ "Slaughter in Zanzibar of Asians, Arabs Told". Los Angeles Times. 20 January 1964. p. 4. ProQuest 168504360. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ a b Plekhanov 2004, p. 91.

- ^ a b Sheriff & Ferguson 1991, p. 241.

- ^ Jacopetti, Gualtiero (Director). (1970)

- ^ Speller 2007, p. 7.

- ^ Ibrahim, Abdullah Ali (June 2015). "The 1964 Zanzibar Genocide: The Politics of Denial". In Eickelman, Dale F.; Abusharaf, Rogaia Mustafa (eds.). Africa and the Gulf Region: Blurred Boundaries and Shifting Ties. Gerlach Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1df4hs4. ISBN 978-3-940924-70-4. JSTOR j.ctt1df4hs4.

- ^ Petterson, Donald (21 April 2009). Revolution In Zanzibar: An American's Cold War Tale. Basic Books. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-7867-4764-1.

Genocide was not a term that was as much in vogue then, as it came to be later, but it is fair to say that in parts of Zanzibar, the killing of Arabs was genocide, pure and simple.

- ^ Salahi, Amr (3 July 2020). "Zanzibar's forgotten legacy of slavery and ethnic cleansing". The New Arab. Archived from the original on 20 July 2024. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ Charny, Israel W. (1999). Encyclopedia of Genocide. ABC-CLIO; Bloomsbury Academic. p. 378. ISBN 978-0-87436-928-1. cites Genocide: Its Political Use in the 20th Century. London, New Haven: Penguin Books, Yale University Press. 1981–1982.

- ^ Siollun, Max (15 January 2016). "How first coup still haunts Nigeria 50 years on". BBC News. Archived from the original on 12 June 2022.

- ^ "Nigeria: Civil war | Mass Atrocity Endings". Tufts University. 7 August 2015. Archived from the original on 17 February 2024.

- ^ Daly 2023, p. 476.

- ^ a b Ekwe-Ekwe, Herbert (9 July 2015). "The Igbo genocide, Britain and the United States (Pt.1)". Pambazuka News. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ^ Daly 2023, pp. 491–492.

- ^ "Nigerian Watch - Free Online Newspaper for Nigerian Community". www.nigerianwatch.com. Archived from the original on 14 November 2023.

- ^ Daly 2023, pp. 494–495.

- ^ "Biafra, scene of a bloody civil war decades ago, is once again a place of conflict". Los Angeles Times. 27 November 2016. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017.

- ^ Frey 2009, p. 83.

- ^ Seybolt, Aronson & Fischhoff 2013, p. 238.

- ^ Heuveline 1998, p. 56.

- ^ Etcheson 2005, p. 119.

- ^ Heuveline 1998, pp. 59–61.

- ^ Mayersan 2013, p. 182.

- ^ Etcheson 2005, p. 114.

- ^ Sliwinski, Marek (1995). Le génocide khmer rouge: une analyse démographique [The Khmer Rouge Genocide: A Demographic Analysis] (in French). L'Harmattan. p. 82. ISBN 978-2-7384-3525-5.

- ^ Sharp, Bruce (1 April 2005). "Counting Hell: The Death Toll of the Khmer Rouge Regime in Cambodia". Archived from the original on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ Rosefielde, Steven (2009). Red Holocaust. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-77757-5.

- ^ a b c Kiernan 2023, p. 518.

- ^ "Resolution adopted by the General Assembly: 57/228 Khmer Rouge trials B1" (PDF). United Nations General Assembly. 22 May 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2007. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ^ a b

- Doyle, Kevin (26 July 2007). "Putting the Khmer Rouge on Trial". Time. Archived from the original on 19 November 2023. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- MacKinnon, Ian (7 March 2007). "Crisis talks to save Khmer Rouge trial". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 November 2007.

- "The Khmer Rouge Trial Task Force". Royal Cambodian Government. Archived from the original on 3 April 2005.

- ^ a b Buncombe, Andrew (11 October 2011). "Judge quits Cambodia genocide tribunal". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 29 August 2024.

- ^ a b c Kiernan 2023, pp. 520–525.