Pacification of Algeria

| Pacification of Algeria | |

|---|---|

| Part of the French conquest of Algeria | |

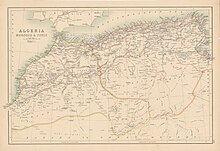

Chronological map of the French conquest | |

| Location | French Algeria |

| Date | 1830–1875 |

| Target | Muslim Algerians |

Attack type | Genocide, ethnic cleansing, forced displacement, chemical warfare, scorched earth |

| Deaths | 500,000–1,000,000[1] |

| Perpetrator | French colonial empire |

| Motive | French nationalism, imperialism, settler colonialism, Islamophobia, anti-Arab racism, Kabyle myth[2] |

The pacification of Algeria, also known as the Algerian genocide,[3][4] refers to violent military operations between 1830 to 1875 during the French conquest of Algeria, that often involved ethnic cleansing, massacres and forced displacement, aimed at repressing various tribal rebellions by the native Algerian population. Out of an estimated population of 3 million, between 500,000 and 1 million Algerians were killed.[5][1][6] During this period, France formally annexed Algeria in 1834, and approximately 1 million European settlers moved to the Algerian colony.[7] Various governments and scholars consider France's actions in Algeria as constituting a genocide.[5][1]

Background

[edit]After the capture of Algiers by France and the defeat of Ottoman troops, France invaded the rest of the country. The end of military resistance to the French presence did not mean that the region was totally conquered. France faced several tribal rebellions, massacres of settlers and razzias in French Algeria. To eliminate them, many campaigns and colonisation operations were conducted over nearly 70 years, from 1835 to 1903.

Campaigns

[edit]First campaign against Abd al-Qadir (1835–1837)

[edit]Tribal elders in the territories near Mascara chose the 25-year-old `Abd al-Qādir (Abd-el-Kader), to lead the jihad against the French. Recognised as Amir al-Muminin (commander of the faithful), he quickly gained the support of tribes in the western territories. In 1834, he concluded a treaty with General Desmichels, who was then military commander of the French Department of Oran. The treaty was reluctantly accepted by the French administration and made France recognise Abd al-Qādir as the sovereign of the territory in Oran Province not under French control, and it authorized him to send consuls to French-held cities. The treaty did not require Abd al-Qādir to recognize French rule, something glossed over in its French text. He used the peace provided by the treaty to widen his influence with tribes throughout western and central Algeria.

D'Erlon was apparently unaware of the danger posed by Abd al-Qādir's activities, but General Camille Alphonse Trézel, then in command at Oran, saw it and attempted to separate some of the tribes from Abd al-Qādir. When he succeeded in convincing two tribes near Oran to acknowledge French supremacy, Abd al-Qādir dispatched troops to move those tribes to the interior, away from French influence. Trézel countered by marching a column of troops out from Oran to protect those tribes' territory on 16 June 1835. After exchanging threats, Abd al-Qādir withdrew his consul from Oran and ejected the French consul from Mascara, a de facto declaration of war. The two forces clashed in a bloody but inconclusive engagement near the Sig River. However, when the French, who were short on provisions, began withdrawing toward Arzew, Abd al-Qādir led 20,000 men against the beleaguered column and, in the Battle of Macta routed the force, killing 500 men. The debacle led to the recall of d'Erlon.

General Clausel was appointed a second time to replace d'Erlon and led an attack against Mascara in December of that year, which Abd al-Qādir, with advance warning, had evacuated. In January 1836, he occupied Tlemcen and established a garrison there before he returned to Algiers to plan an attack against Constantine. Abd al-Qādir continued to harry the French at Tlemcen and so additional troops, under Thomas Robert Bugeaud, a veteran of the Napoleonic Wars experienced in irregular warfare, were sent from Oran to secure control up to the Tafna River and to resupply the garrison. Abd al-Qādir retreated before Bugeaud but decided to make a stand on the banks of the Sikkak River. On July 6, 1836, Bugeaud decisively defeated Abd al-Qādir in the Battle of Sikkak, losing fewer than 50 men to more than 1,000 casualties suffered by Abd al-Qādir. The battle was one of the few formal battles that Abd al-Qādir engaged in; after the loss, he restricted his actions as much as possible to guerilla-style attacks.

In May 1837, General Thomas Robert Bugeaud, then in command of Oran, negotiated the Treaty of Tafna with Abd al-Qādir that effectively recognised Abd al-Qādir's control over much of the interior of what is now Algeria.

Second campaign against Abd al-Qadir (1839–1847)

[edit]Abd al-Qādir used the Treaty of Tafna to consolidate his power over tribes throughout the interior by establishing new cities far from French control. He worked to motivate the population under French control to resist by peaceful and military means. Seeking to face the French again, he laid claim under the treaty to territory that included the main route between Algiers and Constantine. When French troops contested that claim in late 1839 by marching through a mountain defile known as the Iron Gates, Abd al-Qādir claimed a breach of the treaty and renewed calls for jihad. Throughout 1840, he waged guerilla war against the French in the provinces of Algiers and Oran, which Valée's failures to deal with adequately led to his replacement in December 1840 by General Bugeaud.

Bugeaud instituted a strategy of scorched earth, combined with fast-moving cavalry columns like those used by Abd al-Qādir to take territory from him gradually. The troops' tactics were heavy-handed, and the population suffered significantly. Abd al-Qādir was eventually forced to establish a mobile headquarters, which was known as a smala or zmelah. In 1843, French forces successfully raided his camp while he was away from it and captured more than 5,000 fighters and Abd al-Qādir's warchest.

Abd al-Qādir was forced to retreat into Morocco from which he had been receiving some support, especially from tribes in the border areas. When French diplomatic efforts to persuade Morocco to expel Abd al-Qādir failed, the French resorted to military means with the First Franco-Moroccan War in 1844 to compel the sultan to change his policy.

Eventually hemmed between French and Moroccan troops on the border in December 1847, Abd al-Qādir chose to surrender to the French under terms that would allow him to go into exile in the Middle East. The French violated the terms by holding him in France until 1852, when he was allowed to go to Damascus.

Campaign of Kabylia (1857)

[edit]Campaign against El-Mokrani (1871)

[edit]Conquest of the Sahara (1881–1902)

[edit]South-Oranese Campaign (1897–1903)

[edit]

In the 1890s, the French administration and military called for the annexation of the Touat, the Gourara and the Tidikelt,[8] a complex that had been part of the Moroccan Empire for many centuries prior to the arrival of the French in Algeria.[9]

An armed conflict opposed French 19th Corps Oran and Algiers divisions to the Aït Khabbash, a fraction of the Moroccan Aït Ounbgui khams of the Aït Atta confederation. The conflict ended with the annexation of the Touat-Gourara-Tidikelt complex by France in 1901.[10]

In the early 20th century, France faced numerous incidents, attacks and looting by uncontrolled armed groups in the newly occupied areas in the south of Oran.[11] Under the command of General Hubert Lyautey, the French Army's mission was to protect the areas newly controlled in the west of Algeria, near the poorly-defined Moroccan boundaries.[11]

The loose boundary, between French Algeria and the Sultanate of Morocco, promotes incursions and attacks perpetrated by Moroccan tribesmen.[11]

On 17 August 1903, the first battle of the South-Oranese campaign took place in Taghit in which French Foreign legionnaires were assailed by a contingent of more than 1,000 well-equipped Berbers.[11] For 3 days, the legionnaires repelled repeated attacks of an enemy more than 10 times higher in number and inflicted huge losses on the attackers, forcing them finally into a hasty retreat.[11]

A few days after the Battle of Taghit, 148 legionnaires of the 22nd mounted company, from the 2e REI, commanded by Captain Vauchez and Lieutenant Selchauhansen, 20 Spahis and 2 Mokhaznis, forming part of escorting a supply convoy, were ambushed, on September 2, by 3,000 Moroccans tribesmen, at El-Moungar.[11]

Atrocities

[edit]During their pacification of Algeria, French forces engaged in a scorched earth policy against the Algerian population. Returning from an investigation trip to Algeria, Tocqueville wrote that "we make war much more barbaric than the Arabs themselves [...] it is for their part that civilization is situated."[12] Colonel Montagnac stated that the purpose of the pacification was to "destroy everything that crawl at our feet like dogs."[13] The scorched earth policy, decided by Governor General Bugeaud has, had devastating effects on the socio-economic and food balances of the country: "we fire little gunshot, we burn all douars, all villages, all huts; the enemy flees across taking his flock."[13] According to Olivier Le Cour Grandmaison, the colonisation of Algeria led to the extermination of a third of the population from multiple causes (massacres, deportations, famines or epidemics) that were all interrelated.[14]

French forces deported and banished entire Algerian tribes. The great Moorish families (of Spanish origin) of Tlemcen were exiled to the Orient (Levant), and others were emigrated elsewhere. The tribes that were considered too troublesome were banned, and some took refuge in Tunisia, Morocco and even Syria. Other tribes were deported to New Caledonia or Guyana. Also, French forces also engaged in wholesale massacres of entire tribes. All 500 men, women and children of the El Oufia tribe were killed in one night.[15] All 500 to 700 members of the Ouled Rhia tribe were killed by suffocation in a cave.[15] During the Siege of Laghouat, the French army engaged in one of the first instances of recorded use of chemical weapon on civilians and other atrocities causing Algerians to refer to the period as the year of the "Khalya", Arabic for emptiness, which is commonly known to the inhabitants of Laghouat as the year that the city was emptied of its population. It is also commonly known as the year of Hessian sacks, referring to the way the captured surviving men and boys were put alive in the hessian sacks and thrown into dug-up trenches.

Characterisation as genocide

[edit]Some governments and scholars have called France's conquest of Algeria a genocide,[16] such as Raphael Lemkin,[17] who coined the word "genocide" in the 20th century and Ben Kiernan, an Australian expert on the Cambodian genocide,[18] who wrote in Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur on the French conquest of Algeria:[19]

By 1875, the French conquest was complete. The war had killed approximately 825,000 indigenous Algerians since 1830. A long shadow of genocidal hatred persisted, provoking a French author to protest in 1882 that in Algeria, "we hear it repeated every day that we must expel the native and if necessary destroy him." As a French statistical journal urged five years late, "the system of extermination must give way to a policy of penetration."

— Ben Kiernan, Blood and Soil

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Schaller, Dominik J. (2010). "Genocide and Mass Violence in the 'Heart of Darkness': Africa in the Colonial Period". In Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 356. ISBN 978-0-19-923211-6.

- ^ Kiernan, Ben (2007). Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur. Yale University Press. p. 364-374. ISBN 978-0300100983.

- ^ Gallois, William (2013), Gallois, William (ed.), "An Algerian Genocide?", A History of Violence in the Early Algerian Colony, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 145–171, doi:10.1057/9781137313706_7, ISBN 978-1-137-31370-6, retrieved 2024-09-17

- ^ Gallois, William (20 February 2013). "Genocide in nineteenth-century Algeria". Journal of Genocide Research. 15 (1): 69–88. doi:10.1080/14623528.2012.759395. ISSN 1462-3528.

- ^ a b Kiernan, Ben (2007). Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur. Yale University Press. p. 364-374. ISBN 978-0300100983.

- ^ Jalata, Asafa (2016). Phases of Terrorism in the Age of Globalization: From Christopher Columbus to Osama bin Laden. Palgrave Macmillan US. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-1-137-55234-1.

- ^ "Opinion | France must reckon with its dark history in Algeria. It's not too late". Washington Post. 2020-01-29. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2024-09-17.

- ^ Frank E. Trout, Morocco's Boundary in the Guir-Zousfana River Basin Archived 2023-05-23 at the Wayback Machine, in: African Historical Studies, Vol. 3, No. 1 (1970), pp. 37-56, Publ. Boston University African Studies Center: « The Algerian-Moroccan conflict can be said to have begun in the 1890s when the administration and military in Algeria called for annexation of the Touat-Gourara-Tidikelt, a sizable expanse of Saharan oases that was nominally a part of the Moroccan Empire (...) The Touat-Gourara-Tidikelt oases had been an appendage of the Moroccan Empire, jutting southeast for about 750 kilometers into the Saharan desert »

- ^ Frank E. Trout, Morocco's Saharan Frontiers, Droz (1969), p.24 (ISBN 9782600044950) : « The Gourara-Touat-Tidikelt complex had been under Moroccan domination for many centuries prior to the arrival of the French in Algeria »

- ^ Claude Lefébure, Ayt Khebbach, impasse sud-est. L'involution d'une tribu marocaine exclue du Sahara Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, in: Revue de l'Occident musulman et de la Méditerranée, N°41-42, 1986. Désert et montagne au Maghreb. pp. 136-157: « les Divisions d'Oran et d'Alger du 19e Corps d'armée n'ont pu conquérir le Touat et le Gourara qu'au prix de durs combats menés contre les semi-nomades d'obédience marocaine qui, depuis plus d'un siècle, imposaient leur protection aux oasiens »

- ^ a b c d e f "Historique de la bataille d'El Moungar by the French Ministry of Defence". Archived from the original on 2022-07-04. Retrieved 2011-04-30.

- ^ Alexis de Tocqueville, De colony in Algeria. 1847, Complexe Editions, 1988.

- ^ a b Quoted in Marc Ferro, "The conquest of Algeria", in The black book of colonialism, Robert Laffont, p. 657 .

- ^ Colonize Exterminate. On War and the Colonial State, Paris, Fayard, 2005. See also the book by the American historian Benjamin Claude Brower, A Desert named Peace. The Violence of France's Empire in the Algerian Sahara, 1844-1902, New York, Columbia University Press.

- ^ a b Blood and Soil: Ben Kiernan, page 365, 2008

- ^ Gallois, William (20 February 2013). "Genocide in nineteenth-century Algeria". Journal of Genocide Research. 15 (1): 69–88. doi:10.1080/14623528.2012.759395. S2CID 143969946. Archived from the original on 27 May 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ^ Irvin-Erickson, Douglas (2017). Raphael Lemkin and the Concept of Genocide. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-8122-4864-7. Archived from the original on 2024-05-21. Retrieved 2024-02-11.

In the last years of his life, Lemkin developed these ideas most fully in his research on French genocides against Algerians and Muslim Arab culture. In 1956, he collaborated with the chief of the UN Arab States Delegation Office, Muhammed H. El-Farra, to produce an article calling for the UN to charge French officials with genocide. The text that survives in Lemkin's archives contains his annotations and comments. It is notable that El-Farra wrote in language that closely resembles Lemkin's-that France was following a "long-term policy of exploitation and spoliation" in its colonial territories, squeezing nearly one million Arab colonial subjects into poverty and starvation in "conditions of life [that] have been deliberately inflicted on the Arab populations to bring about their destruction." The French authorities, El-Farra continued, "are committing national genocide by persecuting, exiling, torturing, and imprisoning arbitrarily and in conditions pernicious to their health, the Algerian leaders" who are responsible for carrying and promoting Algerian national consciousness and culture, including teachers, writers, poets, journalists, artists, and spiritual leaders in addition to political leaders.

- ^ "Disowning Morris". Archived from the original on 2023-05-08. Retrieved 2019-04-18.

- ^ Kiernan, Ben (2007). Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur. Yale University Press. p. 374. ISBN 978-0300100983. Archived from the original on 2024-05-21. Retrieved 2019-04-18.