Taíno genocide

| Taíno genocide | |

|---|---|

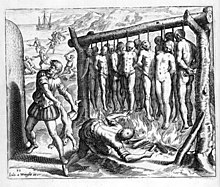

A 16th-century illustration by Flemish Protestant Theodor de Bry for Bartolomé de las Casas' Brevisima relación de la destrucción de las Indias, depicting Spanish torture of Indigenous peoples during the conquest of Hispaniola. | |

| Location | West Indies |

| Date | 1493 - 1550 |

| Target | Taíno |

Attack type | Genocide, mass murder, forced displacement, ethnic cleansing, slavery, starvation, collective punishment, mass rape, forced conversion |

| Deaths | Between 80% and 90% of the Taíno population died in first 30 years.[1][2][page needed] |

| Perpetrators | Spanish Empire |

| Motive | Settler colonialism Spanish imperialism White supremacy |

| Part of a series on |

| Genocide of indigenous peoples |

|---|

| Issues |

The Taíno genocide was committed against the Taíno Indigenous people by the Spanish during their colonization of the Caribbean during the 16th century.[3] The population of the Taíno before the arrival of the Spanish Empire on the island of Hispaniola in 1492[4] (which Christopher Columbus baptized as Hispaniola), is estimated at between 10,000 and 1,000,000.[3][5] The Spanish subjected them to slavery, massacres and other violent treatment after the last Taíno chief was deposed in 1504. By 1514, the population had reportedly been reduced to just 32,000 Taíno,[3] by 1565 the number was reported at 200, and by 1802 they were declared extinct by the Spanish colonial authorities. However, descendants of the Taíno continue to live and their disappearance from records was part of a fictional story created by the Spanish Empire with the intention of erasing them from history.[6]

History

[edit]The Taíno people were the descendants of the Arawak people who arrived in America approximately 4000 years before the conquest, [6] and they lived in the Bahamas, the Greater Antilles and the Lesser Antilles.[7] Christopher Columbus was looking for gold, however, when he did not find it, he focused on the slavery. Upon arriving on the island, a confrontation occurred between the crew of the Santa María and the Taíno after the crew sexually abused Taíno women.[4] In 1503 most of the caciques were captured and burned alive in the Jaragua massacre.[4] Fray Bartolomé de las Casas wrote that in that massacre the Spanish also attacked the other inhabitants, cutting off the children's legs as they ran.[4]

For several months after the massacre, Nicolás de Ovando continued a campaign of persecution against the Taíno until their numbers became very small, [4] according to historian Samuel M. Wilson in his book Hispaniola. Caribbean Chiefdoms in the Age of Columbus. The Taíno suffered physical abuse in the gold mines and sugar cane fields, as well as religious persecution during the Spanish Inquisition, along with the exposure to diseases that arrived with the colonizers.[6] Others were captured and taken to Spain to be traded as slaves, which resulted in numerous deaths due to poor human conditions during the journey.[8]

In thirty years, between 80% and 90% of the Taíno population died.[1][2] Because of the increased number of people (Spanish) on the island, there was a higher demand for food. Taíno cultivation was converted to Spanish methods. In hopes of frustrating the Spanish, some Taínos refused to plant or harvest their crops. The supply of food became so low in 1495 and 1496 that some 50,000 died from famine.[9] Historians have determined that the massive decline was due more to infectious disease outbreaks than any warfare or direct attacks.[10][11] By 1507, their numbers had shrunk to 60,000. Scholars believe that epidemic disease (smallpox, influenza, measles, and typhus) was an overwhelming cause of the population decline of the Indigenous people,[12] and also attributed a "large number of Taíno deaths...to the continuing bondage systems" that existed.[13][14]

Academic discourse

[edit]Academics, such as historian Andrés Reséndez of the University of California, Davis, assert that disease alone does not explain the destruction of Indigenous populations of Hispaniola. While the populations of Europe rebounded following the devastating population decline associated with the Black Death, there was no such rebound for the Indigenous populations of the Caribbean. He concludes that, even though the Spanish were aware of deadly diseases such as smallpox, there is no mention of them in the New World until 1519, meaning perhaps they did not spread as fast as initially believed, and that, unlike Europeans, the Indigenous populations were subjected to enslavement, exploitation, and forced labor in gold and silver mines on an enormous scale.[15] Reséndez says that "slavery has emerged as a major killer" of the Indigenous people of the Caribbean.[16] Anthropologist Jason Hickel estimates that the lethal forced labor in these mines killed a third of the Indigenous people there every six months.[17]

Subsequently, in the United States, Yale University classified the atrocities which the Spanish Empire committed against the Taíno as a "genocide" and it also included the Taíno genocide in its Genocide Studies Program.[3]

Raphael Lemkin considered Spain's abuses of the native population of the Americas to constitute cultural and even outright genocide including the abuses of the encomienda system.[18] University of Hawaii historian David Stannard describes the encomienda as a genocidal system which "had driven many millions of native peoples in Central and South America to early and agonizing deaths."[19] Scholars Bridget Conley and Alex de Waal highlight the weaponisation of starvation employed by conquistadors against the Taíno as being a contributing factor to the genocide,[20] and historian Harald E. Braun highlight Jaragua massacre in 1503 as a case of genocidal massacre.[21]

See also

[edit]- Taíno

- Jaragua massacre

- Colonialism and genocide

- Genocide of indigenous peoples

- Genocides in history

- Indigenous response to colonialism

- List of ethnic cleansing campaigns

- List of genocides

References

[edit]- ^ a b "La tragédie des Taïnos" [The Tragedy of the Tainos]. L'Histoire (in French) (322): 16. July–August 2007.

- ^ a b Diaz Soler, Luis Manuel (1950). Historia De La Esclavitud Negra en Puerto Rico (Thesis). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Hispaniola". Genocide Studies Program. Yale University. Archived from the original on May 22, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Pichardo, Carolina (October 12, 2022). "Anacaona, the Aboriginal chieftain who defied Christopher Columbus and was sentenced to a tragic death". BBC News.

- ^ Fernandes, Daniel M.; Sirak, Kendra A.; Ringbauer, Harald; Sedig, Jakob; Rohland, Nadin; Cheronet, Olivia; Mah, Matthew; Mallick, Swapan; Olalde, Iñigo; Culleton, Brendan J.; Adamski, Nicole (February 2021). "A genetic history of the pre-contact Caribbean". Nature. 590 (7844): 103–110. Bibcode:2021Natur.590..103F. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-03053-2. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 7864882. PMID 33361817.

- ^ a b c Baracutei Estevez, Jorge (October 15, 2019). "Conoce a los supervivientes de un «genocidio sobre el papel»" [Meet the survivors of a "genocide on paper"]. National Geographic (in Spanish). Archived from the original on June 28, 2024.

- ^ Méndez, Luis (October 12, 2022). "Los taínos: los indígenas que se extinguieron en el Caribe tras la conquista española" [The Taínos: the indigenous people who became extinct in the Caribbean after the Spanish conquest]. La Noticia (in Spanish). Archived from the original on May 31, 2024.

- ^ Haczek, Ángela Reyes (October 11, 2022). "Cómo la Conquista de América se cobró la vida de más de 50 millones de personas" [How the Conquest of America claimed the lives of more than 50 million people]. CNN in Spanish (in Spanish). Archived from the original on October 28, 2022.

- ^ D'Anghiera 2009, p. 108.

- ^ D'Anghiera 2009, p. 160.

- ^ Aufderheide, Arthur C.; Rodríguez-Martín, Conrado; Langsjoen, Odin (1998). The Cambridge encyclopedia of human paleopathology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 204. ISBN 978-0-521-55203-5. Archived from the original on 2016-02-02. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ^ Watts, Sheldon (2003). Disease and medicine in world history. Routledge. pp. 86, 91. ISBN 978-0-415-27816-4. Archived from the original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- ^ Schimmer, Russell. "Puerto Rico". Genocide Studies Program. Yale University. Archived from the original on September 8, 2011. Retrieved December 4, 2011.

- ^ Raudzens, George (2003). Technology, Disease, and Colonial Conquests, Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries. Brill. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-391-04206-3. Archived from the original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- ^ Treuer, David (May 13, 2016). "The new book 'The Other Slavery' will make you rethink American history". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 23, 2019. Retrieved June 22, 2019.

- ^ Reséndez 2016, p. 17.

- ^ Hickel, Jason (2018). The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions. Windmill Books. p. 70. ISBN 978-1786090034.

- ^ "Raphael Lemkin's History of Genocide and Colonialism". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Stannard 1993, p. 139.

- ^ Conley & de Waal 2023, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Braun 2023, pp. 626–628.

Works cited

[edit]- Braun, Harald E. (2023). "Genocidal Massacres in the Spanish Conquest of the Americas: Xaragua, Cholula and Toxcatl, 1503–1519". In Kiernan, Ben; Lemos, T. M.; Taylor, Tristan S. (eds.). The Cambridge World History of Genocide. Vol. 1: Genocide in the Ancient, Medieval and Premodern Worlds. Cambridge University Press. pp. 622–647. doi:10.1017/9781108655989. ISBN 978-1-108-65598-9.

- Conley, Bridget; de Waal, Alex (2023). "Genocide, Starvation and Famine". In Kiernan, Ben; Lemos, Tracy Maria; Taylor, Tristan S. (eds.). The Cambridge World History of Genocide. Vol. 1: Genocide in the Ancient, Medieval and Premodern Worlds. Cambridge University Press. pp. 127–149. doi:10.1017/9781108493536. ISBN 978-1-108-49353-6.

- D'Anghiera, Pietro Martire (July 2009). De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 9781113147608. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- Reséndez, Andrés (2016). The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0547640983. Archived from the original on October 14, 2019. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- Stannard, David E. (1993). American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-508557-0.

... estimated population for the year 1769 ... Nationwide by this time only about one-third of one percent of America's population—250,000 out of 76,000,000 people—were natives. The worst human holocaust the world had ever witnessed ... finally had leveled off. There was, at last, almost no one left to kill.