Architecture of Leipzig

The history of the architecture of Leipzig extends from the Middle Ages to the 21st century. Numerous typical buildings and valuable cultural monuments from different eras are still preserved or have been rebuilt. Leipzig, Germany, begins its architectural history with several buildings in the Romanesque style. An example of Gothic architecture in Leipzig is the late Gothic hall vault of the Thomaskirche (1482/1496). In the early modern period, the Old Town Hall was expanded in the Renaissance style. The city experienced the peak of urban design and artistic development from around 1870 to 1914 with historicism, Reformarchitektur and Art Nouveau. Numerous trade fair palaces, commercial buildings, representative buildings such as the Imperial Court Building and the new town hall and the arcade galleries known for the city were built. After the First World War, Leipzig became known for its neoclassicism. During the air raids on Leipzig in World War II , large parts of the city center, which was rich in historic buildings, were destroyed. This was followed in the post-war period by (socialist) neoclassicism and modernism.

Architectural history

[edit]Romanesque and Gothic

[edit]

Leipzig was founded on the site of the later churchyard of St. Matthew as “urbs LIPSK”[1] (Lipa, Linde, Tilia) around 929. The castle urbs LIBZI was first mentioned in 1015 in the chronicle of Bishop Thietmar of Merseburg. The Leipzig art historian Herbert Küas conducted research there between 1950 and 1956. The castle was destroyed in 1217 and the later Leipzig Monastery of the Franciscans was built on this site in 1253. The oldest churches, St. Nicholas (1165) and St. Thomas (1212), are of Romanesque origin. The monastery of St. Thomas and the monastery of St. George were built in the 13th century. The later Katharinenstrasse was named after a Romanesque St. Catherine's chapel consecrated around 1233. The later university church Paulinerkirche emerged from the Dominican monastery founded around 1230. Petersstrasse was also named after the Romanesque chapel of St. Petri.

In the 13th century there were four castles, of which only the Pleissenburg remained as a margrave's castle. In 1270 there was a council consisting of twelve councilors. These were subordinate to a margrave mayor from Pleißenburg.

Important Romanesque buildings in Leipzig are or were:[2]

- The St. Andrew's Chapel in Knautnaundorf is one of the oldest buildings in Saxony; the chapel was built around 1100. The original Romanesque round chapel with a semicircular apse was built based on the model of the round chapel that Wiprecht of Groitzsch had built for his wife at the Groitzsch ancestral castle. At the end of the 15th century, the semicircular apse of the rotunda was demolished. In 1720 a baroque octagon was added to the Romanesque round tower.[3]

- The church in Leipzig-Thekla was built in the 12th century as a massive building made of quarry stone masonry - consisting of a rectangular nave with a rectangular east choir. There is a rectangular tower in the west.[4]

- The foundation walls, walls of the nave and choir as well as the portal of the Gnadenkirche at Rittergutstrasse 2 in Wahren date from the 12th century. Likewise the baptismal font and the door leaf.[5]

- Leipzig's St. Nicholas Church was originally a Romanesque, three-aisled basilica. Remains of the masonry and the westwork with the two corner towers are still preserved from the basilica. From 1784 to 1797 the building was rebuilt in the classicism style based on designs by Johann Carl Friedrich Dauthe (1746-1816).[6]

- The important Gothic Church St. Thomas was built from 1482 to 1496 on the remains of a previous Romanesque building as a late Gothic hall building. The nave still shows the original Gothic ribbed vault with a presumably reconstructed color scheme from the 15th century. The facade comes from historicism (1877–1889).[7]

- Buildings in the Romanesque and Gothic styles

-

St. Andrew's Chapel in Knautnaundorf

-

Church in Thekla

-

Gnadenkirche in Wahren

-

St. Nicholas Church, largest church in Leipzig

-

Church St. Thomas, one of the two main churches in the city

-

Gothic ribbed vault of the Thomaskirche

Leipzig Trade Fair and Renaissance

[edit]

Around 1500 Leipzig had 7,000 to 8,000 inhabitants, but was not as important as Erfurt, which had 13,000 inhabitants at the same time. Through imperial trade fair privileges, the Leipzig Trade Fair was elevated to the status of an Imperial Fair in 1497 and 1507. The provisions of the Leipzig trade fair privilege were particularly at the expense of other regional trading centers such as Erfurt, Halle and Magdeburg, because the privilege of 1507 stated that no trade fair, no fair, no business or sale could be held within a 112 kilometres (70 miles) radius of Leipzig - first of all to visit the Leipzig trade fair and previously all goods were available in Leipzig. This meant that trade fairs in Erfurt, Halle and Magdeburg were prohibited. Leipzig thus developed into a nationally important trading center in central Germany. In Leipzig grew an important merchant bourgeoisie.

For trade, buildings such as the town hall, the armory, the public weigh house, the stables and the granary were built in the Renaissance style, which flourished in Saxony as the Saxon Renaissance. Hieronymus Lotter gave the Old Town Hall its current facade in 1556/1557. The “Leipzig Erker” (Leipzig square oriel window)[8] has had its own tradition in Leipzig since the 16th century. The first stone oriel window was built in 1523 at the Haus zur goldenen Schlange (Golden Snake House). This type of “oriel window became increasingly widespread”.[9] The art historian Wolfgang Haubenreißer notes that Hieronymus Lotter's Renaissance oriel windows in particular influenced the other homeowners. Lotter's works are the single-story box oriel windows from 1556 at the Old Town Hall, the Pappenheim oriel window in the courtyard of the Pleissenburg and the two-story corner bay window on Lotter's home from 1550 at Katharinenstrasse 26.

Important buildings of the Renaissance in Leipzig are or were:[10]

- Alte Nikolaischule (Old school building St. Nicholas), built in 1597. The painted wooden ceiling in the entrance area of the house, the Leipzig coat of arms above the door and the door frame made of Rochlitz porphyry tuff are from the Renaissance and the 16th century.[11]

- Moritzbastei, a two-wing building with a pentagonal floor plan, built by Hieronymus Lotter from 1551 to 1554.[12]

- Public weigh house, built by Hieronymus Lotter in 1555. The scales were inside the house. Leipzig received the rigt for weighing goods in 1507 and weighed and cleared all goods in the public weigh house.[13]

- Old Town Hall (Altes Rathaus), built by Hieronymus Lotter in 1556.[14]

- Buildings in the Renaissance style

-

Public weigh house and north side of the market square

-

Alte Nikolaischule

Leipzig bourgeois town houses and oriel windows of the Baroque era

[edit]

After the Thirty Years' War, Leipzig achieved a leading role in Central Europe as a trade fair city and, thanks to its own trade connections in all directions, it developed into one of the most important trading centers in Europe. The Baroque period began with the construction of the Leipzig Stock Exchange Building and took on an independent, bourgeois form in this city. Leipzig's Katharinenstrasse, Leipzig's market square and Leipzig's Petersstrasse developed into places with bourgeois, four-story magnificent buildings with multi-story, ornately decorated box oriel windows. Since Leipzig was a leader in printing and bookselling, Leipzig also became a trading center for progressive ideas. Outside the city walls, unhindered by guild barriers, numerous manufactory productions emerged, which marked the beginning of Leipzig's industrial development. Trade fairs and manufactories were run by large entrepreneurs who were also bankers who had immigrated to Leipzig from southern and western Germany. The profit earned was immediately invested in baroque buildings.[15]

The “Baroque Leipzig Oriel Window”[16] was influenced by the two-story corner oriel window on Hieronymus Lotter's house from 1550 at Katharinenstrasse 26. The two-story corner oreil window of the Romanus House at Katharinenstrasse 23 corresponded to the oriel window of Hieronymus Lotter's home. An “important link between the Leipzig oriel windows of the Renaissance and those of the Baroque”[9] was the oriel window of the house at Hainstrasse 3, called Weber's Hof. The oriel window from 1662 is two-story and shows decorations from the early Baroque: festoons, putti, cornucopias. Paul Wiedemann's oriel window on the Fürstenhaus (Prince's House), made of Rochlitz porphyry tuff, was influenced by the Torgau Hartenfels Castle (Johann-Friedrich-Bau) from 1533–1536. “A Leipzig special form from the end of the 17th century”[17] are the box oriel windows at Hainstraße 8 and in the courtyard of the Stentzlers Hof exhibition center at Petersstrasse 39 to 41. These oriel windows are “lavishly decorated with vegetal ornamentation”.[18] The box oriel window at Hainstrasse 8 was described as follows: “The stucco work, floral tendrils and a lion's head holding flower garlands still bear witness to the extraordinary quality of the craftsmanship of the time.”[19]

Important Baroque buildings in Leipzig are or were:[20]

- Webers Hof, Hainstrasse 3. Christian Richter designed the house in 1662 in the Baroque style. The two-story oriel window is particularly elaborate: “This… box oriel window… is the oldest oriel window preserved in Leipzig, if not the first oriel window ever built.”[21]

- Old trading exchange (1687). “At that point in time, you probably wouldn't have noticed that Leipzig's first building was built here in a completely new architectural style, which differed greatly from the previously usual geometrically strict forms based on ancient models. Only when the bright façade, decorated with decorative flower and fruit garlands, was completed, did the new baroque splendor emerge. The building by Johann Georg Starcke was the first baroque building in Leipzig."[22]

- The Großbosische Garten (from 1680/1692): This French formal garden was created based on designs by Leonhard Christoph Sturm. Sturm was another Baroque artist who was called to Leipzig and sponsored by Georg Bose.[23]

- Hainstrasse 15, built by Wolfgang Bachmann from 1693 to 1695. The half-timbered house is two window axes wide. An unadorned, wooden, two-story box oriel window extends across the entire width of the facade. Nikolaus Pevsner describes this as an intentional innovation to set itself apart from the ornate oriel windows of the neighboring houses through “simplicity, sobriety and lack of decoration”.[24]

- Romanus House at Katharinenstrasse 23, built from 1701 to 1704 by Johann Gregor Fuchs.[25]

- Knauthain Castle and Apel's Garden (from 1702). These were designed according to designs by David Schatz, who lived in the house at Neumarkt 13 in Leipzig, which he himself had built according to his design.[26] Cornelius Gurlitt describes David Schatz's architectural style as follows: "From these buildings one can see a progression from simple Dutch forms to Baroque, the latter expressed more in added ornament, not in an inner liberation."[27]

- Torhaus Dölitz, Helenenstrasse 24. The model was the architectural style of Cornelius Floris : the “earliest evidence of the transition from the Renaissance to the Baroque, which was based on Nordic models ”.[28]

- Königshaus (Royal house) at Markt 17, built from 1705 to 1706 by Johann Gregor Fuchs.[29]

- Fregehaus at Katharinenstrasse 11, rebuilt by Johann Gregor Fuchs from 1706 to 1708 using still visible Renaissance components from around 1535 (portals). The builder was Gottfried Otto.[30]

- Bosehaus at Thomaskirchhof 16, built by Nikolaus Rempe from 1711 to 1712. The builder was Georg Heinrich Bose.[31]

- Schillerhaus at Menckestrasse 42 in Gohlis, built in 1717 in the Baroque style.[32]

- The house Zum Arabischen Coffe Baum (House of the Arab Coffee Tree) at Kleine Fleischergasse 4, built by Adam Jacob from 1717 to 1719.[33]

- Hainstrasse 13, built by George Werner from 1744 to 1746. The three-story box oriel window is made of stone and stucco. The side surfaces are slightly concave.[34]

- House of the Golden Snake (Barthels Hof), built by George Werner from 1747 to 1750.[35]

- House Zum Grönländer (At the Greenlander) at Petersstrasse 24/Sporergäßchen, built by George Werner from 1749 to 1750.[36]

- Aeckerlein's Hof. Peter Hohmann had the building built in the Baroque style by Johann Gregor Fuchs and Christian Schmidt from 1708 to 1714.

- Griechenhaus (House of the Greeks) at Katharinenstrasse 4, built in 1640.

- Hohmanns Hof at Petersstrasse 15. Peter Hohmann had the building built by George Werner in the Baroque style between 1728 and 1731.

- Jöcher's House: Merchant Johann Christoph Jöcher had the building built in 1707 by Johann Gregor Fuchs in the Baroque style. The portal with the female figures on the balcony was created by Christian Döring in 1736.

- Koch's Hof: The banker Michael Koch had the building built between 1735 and 1739 based on designs by George Werner.

- Hainstrasse 8: The oldest surviving town house in Leipzig at Hainstrasse 8 dates from around 1550 to 1560. It was the construction period of the Renaissance, when solid construction replaced half-timbered construction. Half-timbered buildings themselves were banned in Leipzig in 1559. The builder was Antonius Lotter, brother of the municipal builder Hieronymus Lotter. At the beginning of the 18th century, the building received an elaborately designed, baroque box oriel window.[37] Russian students who were trained in Leipzig in the 1760s on the orders of Tsarina Catherine the Great also lived here, according to Alexander Nikolayevich Radishchev.

- Baroque houses and oriel windows in Leipzig

-

Königshaus (Royal House) at the Markt

-

House Zum Grönländer (At the Greenlander)

-

Fregehaus

-

Stentzlers Hof

-

Jöcher's House (1930)

More pictures can be found here.

Rococo (18th century)

[edit]

Gurlitt[38] describes that in the 1830s, Rococo also appeared in Leipzig in the forms that Jean de Bodt, Zacharias Longuelune and Johann Christoph Knöffel used in the neighboring Saxon Dresden.

Gurlitt describes Rococo buildings in Leipzig.[38] The Rococo style was represented in Leipzig by George Werner, who had a preference for grouping the windows on an axis across different floors with lesenes. Rococo buildings in Leipzig are or were:

- Katharinenstrasse then number 27 (now 19): The facade is nine axes wide with four upper floors. The building mixes the Knöffel style with the Baroque style. The portal was still Baroque with corner pilasters and a curved cornice over the basket arch of the door.[39] The preserved building is also called Hannsen's House after its builders, Justus and Ludolph Hannsen. The Hannsen brothers had it designed by George Werner in the Rococo style between 1748 and 1749. Here, too, windows across the four upper floors were grouped into vertical groups with lisenes. The windows in the central axis of the facade are roofed, and there are rocailles underneath. There are also rocailles in the wall panels under the side windows.[40]

- Markt number 5: lesenes house in the Longuelune style with elaborate infill panels for the delicately rich rococo gable.

- Markt number 14: Large building with simple architecture. There is a “simple, cleaned mirror” between the simply rectangular or eared windows on the different floors.[41]

- Hainstrasse No. 11 and Fleischergasse No. 19: The rear building had two oriel windows. On the front building there was a coat of arms with two crossed anchors. The house received “slightly curved ornaments under the oriel windows” on both facades[42] and was “beautified on both Hainstrasse and Fleischergasse during the Rococo period”.[42]

- Katharinenstrasse No. 7: Building with simpler Rococo ornaments that is only three window axes wide. The house stands at the end of the Rococo era in Leipzig: “The building probably marks the end of the direction that culminates in Katharinenstrasse No. 29.”[43]

- Universitätsstraße No. 18 Silberner Bär (Silver Bear):[44] The client was the music publisher Johann Gottlob Immanuel Breitkopf (1719–1794), who had it rebuilt in 1765. Its axis towards Universitätsstrasse was designed in “rough Rococo”.[44] Originally there was an elaborately designed, large portal on the ground floor, above which a bear holds a cartouche. The stucco ornamentation was handled in a very special way here: “The crowning of the windows is typical of the handling of the stucco ornamentation at that time.”[44]

- Councilor and merchant Gottlieb Beck had the house at Klostergasse 5 designed by George Werner from 1740 to 1741 in the Rococo style. The building is located on the site of the former St. Thomas Monastery, which is why it is also known as the Old Monastery.[45]

- Peterstrasse No. 24. Very stately but simple house with many simply used lesenes in the Knöffel style and with rococo decoration on the oriel windows, which extend over three upper floors.[46]

- Peterstrasse Nr. 13

- Corner of Reichsstrasse and Brühl Rother Löwe (Red Lion)

- Reichsstrasse Nr. 38

- Katharinenstrasse No. 29 (today 21): The builder was Gottfried Winckler, who ran his company, as well as a banking and exchange business as well as a spice trade, in his house, which had belonged to the Winckler family since 1654 and also served as a residential building. The building was strongly influenced by Knöffel's lesenes architecture: "Lesenes through the three upper floors in the style of Knöffel, with Rococo ornaments in the parapets."[47] At the same time, the building was the highlight of Leipzig's bourgeois Rococo - "the one in Katharinenstrasse No. 29 culminating direction.”“[43] The ground floor was divided into three parts, the courtyard was closed, the attic was in the back of the house, and the writing rooms were on the right. The staircase to the upper floor was particularly elaborate. This was covered with Delft tiles on the parapet. The rooms on the first floor had good parquet floors, complete paneling on the walls and beautiful doors with elaborate profiling, as well as a ceiling painting by Adam Friedrich Oeser.

- Another Rococo building in Leipzig is the Gohlis Palace.

- Rococo lesenes architecture in Leipzig

-

Katharinenstrasse then 27 (now 19) was also Hannsen's house

-

Katharinenstrasse No. 29 (today 21)

-

Old Monastery, Klostergasse 5

Rapid urban development and neoclassicism (19th century)

[edit]

The Leipzig Trade Fair and the associated market advantages played an important role in Leipzig's industrial development. New exhibition buildings were created for the new form of the sample fair. In addition, Leipzig's extensive banks and financial markets were important for the city's industrial development, for which the Alte Handelsbörse (old trading exchange) was used. Another factor in development was Leipzig's early railway connection to raw material and sales markets. The suburbs became densely built-up mixed areas consisting of working-class residential areas and industrial and commercial facilities. The mixed areas grew together with the newly created industrial suburbs in the former village surroundings of Leipzig. As a result, Leipzig's population increased from 33,000 in 1815 to 100,000 around 1870. Leipzig was now one of the leading industrial cities in Germany.

In those times of a rapid urban development the style of neoclassical architecture was prevalent. Representatives of classicism in Leipzig were Friedrich Weinbrenner, Eduard Pötzsch, Albert Geutebrück, Johann Carl Friedrich Dauthe and Carl Gotthard Langhans.

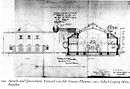

The Old Leipzig Theater,[48] built in 1766, was rebuilt in 1817 by Friedrich Weinbrenner in the neoclassicism style. The plain west side was redesigned by Weinbrenner into a “representative, classicist entrance front”.[49] The front curtain painted by Adam Friedrich Oeser was replaced in 1799 by a curtain by Hans Veit Schnorr.

Eduard Pötzsch designed the masonic lodges Apollo and Balduin zur Linde (1847), the Hotel de Pologne, the Leipzig Dresdner Bahnhof train station and the Leipzig Bayerischer Bahnhof train station in the neoclassicist style.

According to James Stevens Curl, Karl Friedrich Schinkel is the “greatest German architect of the first half of the 19th century”.[50] Albert Geutebrück designed the building using Schinkel's facade design for the university building Augusteum. What remains is the portal of the old university (Schinkel gate). According to Schinkel's designs, Geutebrück also built the three-story, fifteen-axis building of the former Schützenhaus (today Wintergartenstrasse) from 1833 to 1834.[51] Geutebrück also built: Großer Blumenberg, the Post Office Building on Augustusplatz, the Booksellers' Exchange Building and the Royal Palace.

The concert hall[52][53] was built from 1780 to 1783 in the armory wing of the Gewandhaus under the direction of the building director Johann Carl Friedrich Dauthe in the classicist style. The ceiling was painted by Adam Friedrich Oeser, but in 1833 it was painted over with an architectural painting by Johann August Giesel from Dresden. Dauthe designed the banker Löhr's garden house (1772) and rebuilt the interior of the late Gothic Leipzig Nikolaikirche (1785 to 1796) in the neoclassicist style.

The New Leipzig Theater[54] was built on the north side of Augustusplatz between 1864 and 1867 in the neoclassicist style based on designs by the late Royal Prussian Building Councilor Carl Gotthard Langhans, architect of the Royal Opera House (today: Berlin State Opera) in Berlin. The Royal Prussian Building Council's designs for the Leipzig City Theater were based on the Royal Opera House in Berlin, which was also remodeled by Langhans in the neoclassicist architectural style. The façade facing the Schwanenteich (swan pond) showed parallels to the Acropolis of Athens. Like the Erechtheion located there, the New Leipzig Theater had a vestibule facing the swan pond, which was supported by six larger-than-life girl figures (caryatids) instead of columns.

The Roman House was built in 1832/1833 based on designs by Woldemar Hermann for the publisher Hermann Härtel. Although it has neoclassicist elements, it is seen as the beginning of the Neo-Renaissance in Leipzig according to its model and intention.[55] It was based on the Villa Farnesina in Rome, a building of the High Renaissance, and, like this Roman villa, featured a five-arched loggia. The building was known for its paintings, including the seven-panel Odysseus cycle and the six-panel Cinderella cycle. The house became Ernst Ziller's model for the realization of Heinrich Schliemann's Renaissance residential palace Iliou Melathron in Athens.

A garden hall in the Roman house contained the Odysseus cycle. The artist was Friedrich Preller the Elder.[56] The boxes of the Odysseus cycle, created based on the frescoes, were exhibited in the Municipal Museum on Augustusplatz. The Preller frescoes were moved to the walls of the stairwell of the university library before the house was demolished in 1904, but were destroyed in the Second World War.

The ballroom of the house showed six individual pictures of Cinderella in wax colors based on Moritz von Schwind's picture cycle from 1852 to 1854. The artist was Julius Naue, who painted the cycle from 1873 to 1875. When the house was demolished in 1904, the paintings and masonry were sawn out of the walls and installed in the auditorium of the II Higher Girls' School[57] (today the Gaudig School) in 1907. When the Workers and Farmers Faculty moved into the Gaudig School building in 1949, four paintings were replaced by contemporary images. Two of the paintings are now in the foyer of the Leipziger Volkszeitung publishing house.

- Neoclassicism buildings

-

Großer Blumenberg

-

Schützenhaus 1835 (later part of the Krystallpalast)

-

Augusteum before the restructuring

-

Aula of the Augusteum

-

New post office building around 1840

-

Booksellers' Exchange Building 1840

-

Royal Palace (Königliches Palais) of the Leipzig University

-

New Leipzig Theater

-

Hotel de Pologne, frescoes (selection)

-

Neoclassicistic ceiling of the St. Nicholas Church

Franco-Prussian War and historicism (from 1871)

[edit]

After Germany's victory in the Franco-Prussian War and the subsequent continuous French reparation payments, there was an economic upswing and a construction boom in Germany in the style of historicism. The Victory Monument in Leipzig, which commemorated Germany's victory and was erected on the Leipzig market square in 1888, was demolished in 1946 because it "symbolized militarism".[58] The monument, created by Rudolf Siemering from the Berlin School of Sculpture, consisted of the allegory of Germania as well as depictions of various historical personalities of Saxony and the Wilhelmine Empire: the German Emperor Wilhelm I, the German Emperor Frederick III, King Albert of Saxony, Reich Chancellor Bismarck and Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke.

Between 1871 and 1914, Leipzig's population rose from 100,000 to 625,000. The suburbs were incorporated. It started in 1889 with Reudnitz and Anger-Crottendorf. Thonberg, Sellerhausen, Volkmarsdorf, Gohlis and Eutritzsch followed in 1890. In 1891 came Lindenau, Plagwitz, Schleußig, Kleinzschocher, Connewitz, Lößnig. In 1910 they were Dölitz, Dösen, Probstheida, Stötteritz, Stünz and Möckern.[59]

According to Wolfgang Hocquél, Leipzig's historicism is important: "The largest share of the 1,410 listed buildings in the city of Leipzig is made up of around 700 residential buildings of historicist architecture...". Representatives of historicism in Leipzig were August Friedrich Viehweger, Martin Gropius, Heino Schmieden, Hugo Licht, Paul Richter, Arwed Roßbach, Hans Enger, Karl Weichardt and Otto Simonson.

According to the art historian and monument conservator Wolfgang Hocquél, the Leipzig passages and courtyards are cultural monuments of European importance.[60] There are world heritage efforts in Leipzig to specifically honor this cultural era, which left unique traces in the city.

Italian Neorenaissance

[edit]The empire, which was created when the empire was founded in 1871 after winning the Franco-Prussian War, located its highest court, the Reichsgericht, in Leipzig. The building was designed in the Italian Neo-Renaissance style.[61] After the founding of the empire, the “style of the Italian Renaissance was propagated as a national style ”.[62] The Italian Neo-Renaissance was based on Renaissance architecture. The essential design elements of Classical antiquity were adopted. Numerous buildings were built around the Imperial Court that “took up the formal language of the Renaissance”:[61] the New Concert House, the Municipal Museum, the Reich Post Office Building, the New Commercial Exchange (Neue Börse), the University Library, the Royal Conservatory of Music , the Royal Academy of Arts and the School of Applied Arts (design by Otto Warth) and a polytechnic.

Reich Court Building

[edit]The Reich Court Building was created in the style of historicist architecture based on models from the Italian Renaissance. The Reich Court building was built from 1888 to 1895 based on designs by Ludwig Hoffmann and Peter Dybwad. The dome is decorated with the sculpture The Truth. Other figures from German legal history decorate the building, including Eike of Repgow, Johann of Schwarzenberg, Johann Jakob Moser, Carl Gottlieb Svarez (General State Laws for the Prussian States), Paul Johann Anselm Ritter von Feuerbach and Friedrich Carl von Savigny. The interior furnishings, including the figurines and wall decorations, deal with the themes of investigation, judgment, execution and mercy.

- Reich Court Building

-

Historicism: Reich Court Building

-

Historicism: Reich Court Building, floor plan

Zweites Gewandhaus

[edit]

The New Concert Hall[63] in the music district was built between 1882 and 1884 based on designs by Martin Gropius and Heino Schmieden and opened on 11 December 1884. The building contained two concert halls, changing rooms and music rooms. The main hall was 37.5 metres (123 feet) long and 19 metres (62 feet) wide. The hall was 14.6 metres (48 feet) high. The historicist facade was based on the classical Renaissance: "The facade was designed entirely in the spirit of the Hellenic Renaissance direction cultivated by Gropius and in closer connection to Schinkel's Konzerthaus Berlin."[64] Otto Lessing created the architectural decoration. The structure became the model for the Symphony Hall in Boston, built in 1900. The Mendelssohn Monument stood in front of the building until 9 November 1936, created based on a design by Werner Stein and inaugurated on 26 May 1892. It was demolished at the instigation of Rudolf Haake, deputy of Mayor Carl Goerdeler, during his absence and the statue probably melted down. Damaged during the Bombing of Leipzig in World War II, the ruins of the second Gewandhaus were demolished on 29 March 1968.

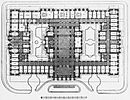

Municipal Museum

[edit]The core of the Municipal Museum on Augustusplatz consisted of a work by the Munich architect and professor Ludwig Lange in “Italian Renaissance forms”[65] from 1855. At the end of 1881, an application was submitted to significantly enlarge the building based on a design by Hugo Licht. The design was further supplemented by Baron Heinrich von Ferstel in Vienna and Heino Schmieden from Berlin. The construction costs were financed with 600,000 marks from the assets of Franz Dominic Grassi. In addition, Grassi donated another 99,200 marks to renovate the inner main staircase. The eastern loggia of the old building, which was painted by Professor Theodor Grosse, was built up as a result of the work. Since the loggia no longer received any light from outside, a large skylight room was created in front of the loggia. In a mirror image, a loggia was also created on the western side with indirect lighting through a skylight hall in front of it. The renovation took place from 1883 to 1886.[66]

The facades were made of ashlar, the figurative decorations were made of Istrian limestone. It was built according to models of the “Italian High Renaissance.”[67] The forms were “made to appear somewhat more energetically […] than they were in Lange 's original building.”[67] The main staircase was made of Salzburg marble, Istrian limestone and polished granite. The vaults under the skylights and ceilings showed picturesque decoration.[67]

According to a design by the Leipzig architect Hugo Licht, the Royal Conservatory of Music was built between 1885 and 1887 at Grassistrasse 8 in the music neighbourhood (Musikviertel) in Leipzig-Mitte and inaugurated on 5 December 1887.

- Municipal Museum

-

Historicism: Municipal Museum on Augustusplatz

-

Historicism: Municipal Museum on Augustusplatz, upper floor

-

Historicism: Municipal Museum on Augustusplatz, ground floor

Reichspost building

[edit]The Reichspost building[68] was rebuilt from 1881 to 1884 by Paul Richter in the style of historicism based on models of the Italian Renaissance: “The facades are partly made of ashlar and partly made of fine brick in the special forms of the Saxon school of the Italian Renaissance”.[69] The material of the architectural structures consisted of sandstone. The smooth surfaces were plastered. The Reichspost and Telegraph Administration building had three main floors with large hall-like rooms. The property covered 3,920 square metres (42,200 square feet), of which 2,824 square metres (30,400 square feet) was built and 1,096 square metres (11,800 square feet) was open space. Joseph Kaffsack created six 4 metres (13 ft) tall attic statues on the main post office, which were commissioned by the Reichspost and Telegraph Administration and were allegories of postal services, telegraphy, art, science, trade and industry. The allegorical figure with wings represented the most modern form of message transmission at the time, telegraphy. This figure was juxtaposed with a second figure, also winged, which symbolized postal mail. The other four wingless figures in between represented trade, art, science and industry. This arrangement of figures indicated the importance of rapid message transmission.[70]

- Main Post Office

-

Historicism: Reichspost building

-

Historicism: Reichspost building, floor plan

Fashion house August Polich (until 1936)

[edit]

Towards the end of the 19th century, the era of large universal and specialty department stores began in Leipzig, including the Leipzig fashion store Gustav Steckner and the Leipzig department store Althoff, between Neumarkt, Petersstrasse and Preußergäßchen. The southern entrance to Petersstrasse was adorned on the left by the representative August Polich fashion house, which was demolished during the Nazi dictatorship. Roßbach provided the designs for the Polich department store at Markgrafenstrasse 2/Petersstrasse/Schloßgasse. The building, equipped with an escalator, was built around 1888 and expanded in 1898.[71] August Polich's department store group also had its own mail order business and laundry factories. The purveyor to the court, August Polich, Leipzig, was next to Rudolph Herzog , Berlin; Hermann Gerson , Berlin; N. Israel, Berlin; Abraham Wertheim , Berlin in the Verein zur Abwehr des Antisemitismus (Association for the Defense of Anti-Semitism).[72] In the 30th volume of Merian, Heinz Maegerlein describes his experiences in the old Jewish Leipzig and the Jewish department store Polich. Maegerlein describes Leipzig as an “extraordinarily complex city”,[73] including Leipzig as a city of the fur trade and “industry”: [73]

"... and the Jews in Brühl, the most important fur street in the world at the time, in their black caftans, trading and gesticulating animatedly in front of their shops, with their side-locks that seemed so alien to us ... and the first escalator of our lives in August Polich's progressive department store next to the Deutsche Bank at the exit from Petersstrasse.”

— Heinz Maegerlein, 1977[73]

- Fashion house August Polich

-

Polich Jewish department store demolished in 1936 (left)

-

August Polich commercial building, floor plan and cross section, 1892

-

August Polich commercial building, escalator, 1900

Neue Handelsbörse (New trading exchange building)

[edit]

The Neue Handelsbörse (New trading exchange building)[74] at Tröndlinring 2 was built from 1884 to 1887 according to designs by the architects Hans Enger and Karl Weichardt in the style of historicism based on models of the Italian Renaissance: “The architecture outside and inside is carried out in the Italian High Renaissance”.[75] On the ground floor there was a 600 square metres (6,500 square feet) main hall for the trading exchange and another 280 square metres (3,000 square feet) hall for the grain exchange, another 180 square metres (1,900 square feet) hall as well as a reading hall and the meeting room of the Chamber of Commerce. The built area was 2,400 square metres (26,000 square feet).

- Neue Handelsbörse (New trading exchange building)

-

Neue Handelsbörse, chamber of commerce meeting room and stock exchange hall

-

Neue Handelsbörse, cross section

-

Neue Handelsbörse, floor plan

Villas and townhouses

[edit]

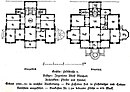

Numerous residential buildings were also built in the Italian Neo-Renaissance style: the architects Hermann Ende and Wilhelm Böckmann created a two-story villa with a porch in the shape of an ancient triumphal arch. The building, built in 1876/77, was located at Sidonienstrasse 13 and was built for the commercial councilor Julius Meißner.[76] In 1890–1891, the architectural firm Pfeifer & Händel created a large villa at Feldstrasse 3 (today Lützowstrasse 9) in Leipzig-Gohlis for the engineer and founder Adolf Bleichert, owner of the largest cable car factory. The facades were made of Postelwitz and Cotta sandstone.[77] The building was named Villa Hilda after Bleichert's wife Hildegard. The dome and a side projection were destroyed in 1945. Since 1956 the building has been called the Klubhaus Heinrich Budde, after a former technician from the Bleicherts company; Interior renovations were made.[78][79]

In 1882, Heino Schmieden from Berlin created the four-story, seven-window-wide residential building at An der Pleiße 9–10 for the banker Max Meyer. On the sides of the building there were two-story bay windows with caryatids and a tympanum above. A spacious portal with a balcony above marked the entrance area.[80]

In 1885/86 Max Pommer created the second Villa Meyer at Plagwitzerstrasse 55 (today Käthe-Kollwitz-Strasse 115) for the publishing bookseller Herrmann Julius Meyer.[81] After a general renovation, the building received the Denkmalpflegepreis (monument preservation award) in 2004.

Another building in the Italian Neo-Renaissance style was the Villa Giesecke, built in 1899 by the Berlin government architect Max Hasak for the type foundry owner Georg Giesecke at Carl-Tauchnitz-Straße 37 (today Karl-Tauchnitz-Straße 21).[82]

Bruno Grimm created a four-story urban house with 12 window axes in the Italian Neo-Renaissance style in 1880 for the factory owner H. L. Wolff at Täubchenweg 1.[83] The architect Gustav Strauß created the four-story house at Promenadenstrasse 1 from 1881 to 1882.[80] The Architect and professor at the Art Academy Constantin Lipsius built the building at Königstrasse 33 for Ernst Keil's widow in 1861. The three-story building was decorated with an elaborate central Avant-corps and corner core.[84]

Max Bösenberg created two four-story residential buildings in the Italian Neo-Renaissance style on Stephanstrasse in Leipzig. The facades were divided into 15 window axes, the central and corner axes were emphasized like an avant-corps. Bösenberg built the semi-detached house at Stephanstrasse 10/12 for the Naumann brothers between 1882 and 1883.[85] In the years 1881–1882, Bösenberg created the semi-detached house at Stephanstrasse 16/18 for C. A. Schulze.[86] The two buildings built by Bösenberg on Stephanstrasse have been preserved.

Another four-story residential building, which was 17 window axes wide, stood at Stephanstrasse 14 and was built in 1880/1881 for the bookseller Franz Köhler based on plans by Karl Weichardt.[87]

For Moritz Lazarus, the Leipzig architect Steib built a five-story residential and commercial building at Packhofstrasse 11-13 from 1865 to 1866 that was 15 axes wide. The middle part was decorated with colossal columns that supported a gable triangle.[88] Lazarus was an internationally renowned Jewish scholar and champion of Jewish emancipation, co-founder and long-time vice-president of the Deutsch-Israelitischer Gemeindebund (German-Israelitic Community Association), an umbrella organization of Jewish communities in Germany, founded in Leipzig in 1869 and expelled from Saxony in 1882. Alexander Rapaport (1833–1910), a fur trader, and his wife Maria Rapaport (1841–1912) lived in the building at Packhofstrasse 11–13. The Jewish company Hundert &/ Co., which traded in linen and cotton goods and had a branch at Hainstrasse 5, also had its headquarters in the house.[89]

Arwed Roßbach built a villa for the Leipzig merchant August Louis Davignon in 1880/1881. Roßbach also built a villa with a sandstone-clad facade in the Italian Renaissance style with stairs and terraces for the publishing bookseller Leopold Gebhardt (1880/1881). In 1894 Roßbach built Villa Swiderski for the manufacturer Philipp Swiderski ; well-known residents were Rudolf Swiderski and Hans Heinrich Reclam. The war-damaged villa was blown up in 1947. Roßbach built the building at Weststrasse 15 in Leipzig from 1874 to 1876 for Consul General Alfred Thieme. The construction costs for 1 square metre (11 square feet) of built area were 230 marks at that time. Roßbach built the Villa Gruner at Karl-Tauchnitz-Straße 19 (old Carl-Tauchnitz-Straße 35) in the neo-renaissance style for the city councilor R. Gruner from 1886 to 1887. The construction costs for 1 square metre (11 square feet) of built area were 335 marks.[90]

Max Pommer built the Villa Oelßner at Karl-Tauchnitz-Straße 13 (old Carl-Tauchnitz-Straße 29) for Wilhelm Oelßner in 1888. The construction costs for 1 square metre (11 square feet) of built area were 350 marks. Pommer also built Villa Ledig between 1881 and 1883.[91]

- Photographs

-

House Gebrüder Naumann, Stephanstraße 10–12

-

Villa Georg Giesecke

-

House Oldenbourg, Schillerstraße 6

-

House C. A. Schulze, Stephanstraße 16–18

-

Villa Adolf Bleichert

-

Villa Ernst Keil

-

Villa Julius Meißner

-

Villa Davignon

-

Villa Gebhardt

-

Villa Swiderski

-

Villa Gruner

-

Villa Thieme

-

Villa Oelßner

-

Villa Ledig

- Floor plans

-

Floor plan by Bösenberg for House Naumann, Stephanstraße 10–12

-

Floor plan by Hasak for Villa Georg Giesecke

-

Floor plan by Aeckerlein for House Oldenbourg, Schillerstraße 6

-

Floor plan by Bösenberg für House Schulze, Stephanstraße 16–18

-

Floor plan by Pfeifer for Villa Adolf Bleichert

-

Floor plan by Lipsius for Villa Ernst Keil

-

Floor plan by Ende & Böckmann for Villa Julius Meißner

-

Floor plan by Roßbach for Villa Davignon

-

Floor plan by Roßbach for Villa Thieme

-

Floor plan by Roßbach for Villa Gruner

-

Floor plan by Pommer for Villa Oelßner

-

Floor plan by Pommer for Villa Ledig

Hotels, restaurants and coffee houses

[edit]

The oldest café in the city since 1711 and therefore one of Europe's oldest coffee bars is the baroque house Zum Arabischen Coffe Baum (“ Arabian Coffe Tree ”).

One of the best-known cafés was Café Metz in the Otto-Schill-Strasse 2 building. The two houses on the Dorotheenpassage (Otto-Schill-Strasse 1 and 2) were built in 1890/91 by the Leipzig architect and owner Paul Jacobi in the historicist style with a dome and corner oriel windows. Both buildings look like the gateway to the Colonnade Quarter (Kolonnadenviertel). They were designed to be identical mirror images and were each crowned with an onion-shaped dome in neo-Renaissance style. The café inside was lavishly decorated with stylized flowers. The building at Otto-Schill-Strasse 2 has been preserved and is since 2017 home of several offices of the city administration.[92]

The most famous hotel in Leipzig was the “Hotel Kaiserhof” at Georgi-Ring 7. The owner of the hotel was Robert Börner, a traiteur and Royal warrant of appointment. The building was built in 1889 according to designs by the architect Julius Zeißig in the style of historicism based on the model of “Baroque Renaissance”.[93]

The ground floor contained the porter's lodge, an office, a reading room, a small hall and a grand hall. The stairwell was lit by large windows. The steps were made of Carrara marble. The grand hall showed large paintings of the German Kaiser family.

- Historic hotels and coffeehouses

-

Hotel Kaiserhof, stairs

-

Hotel Kaiserhof, Small Hall

-

Dorotheenpassage, Café Metz

-

Otto-Schill-Strasse 1 and 2 (Dorotheenpassage)

German Renaissance Revival Architecture

[edit]

The Deutsches Buchhändlerhaus (German Booksellers House) was completed in 1888 based on designs by Kayser & von Großheim. The ballroom featured murals by Woldemar Friedrich, as well as a glass painting entitled Leipzig as the Center of the German Book Trade. The Leipzig bookseller's house was created in the style of historicism: "The façade design of the entire complex is an excellent achievement of the German Renaissance Revival style."[94] As a counterpart to the bookseller's house, the Deutsches Buchgewerbehaus (German Book Trade House) was built in the Graphic Quarter, which was also connected to the Leipzig book trade. The Renaissance Rivaval building, built by Emil Hagberg from 1898 to 1901, served to present the products of the graphic industry. Another building in the German Renaissance Revival style was the Villa Wölker at Karl-Tauchnitz-Straße 15 (old 31), which was completed in this style in 1888 for Consul General Wilhelm Wölker based on designs by Max Pommer.[95] The Villa Rehwoldt at Karl-Tauchnitz-Straße 29 (old 45) and the Villa Fritzsche at Karl-Tauchnitz-Straße 37 (old 55) were also built according to designs by Max Pommer. Hugo Licht also designed the New Town Hall in the German Renaissance Revival architecture style. Gerhard Weidenbach and Richard Tschammer designed the Reformed Church in the style of the German Renaissance Revival Arhitecture (1896/99). The Huguenot cross on the church tower commemorates the origins of the members of Leipzig's Reformed community, who fled Catholic France as Huguenots.[96]

- Buildings in the German Renaissance Architecture style

-

Villa Fritzsche, Karl Tauchnitzerstrasse 37 (old 55), designed by Max Pommer (1898)

-

Villa Rehwoldt, Karl Tauchnitzstrasse 29 (old 45), designed by Arwed Roßbach (1898)

-

Villa Wölker, Karl Tauchnitzstrasse 15 (old 31), designed by Max Pommer (1900)

-

Deutsches Buchhändlerhaus in Leipzig (German Bookseller's House, around 1900)

-

Deutsches Buchgewerbehaus (German Book Trade Building, around 1900)

-

Reformed Church (Reformierte Kirche) (2009)

Gothic Revival architecture

[edit]The building “Die Gute Quelle”, Brühl 42, was completed in the Gothic Revival architecture style in 1867 based on designs by the architect August Friedrich Viehweger. The client was the fur trader E. B. Lomer.[97] A sacred building in the Gothic Revival style was the Leipzig University Church of St. Pauli, designed by Arwed Roßbach. St. Peter's Church was built in this style in 1882/1885 according to designs by the architects August Hartel and Constantin Lipsius.

The tower of the Leipzig Central Market Hall was stylized in a Gothic Revival style based on the model of the campanile of the Florentine Palazzo Vecchio between 1889 and 1891 according to plans by the city planning director Hugo Licht.[98]

- Buildings in the Gothic Revival architecture style

-

Historicism: Paulinerkirche

-

Historicism: Lomer commercial building, architect: August Friedrich Viehweger, 1867

-

Historicism: Peterskirche

Moorish Revival architecture

[edit]

Hannelore Künzl describes how Otto Simonson mixed elements from different periods when building the Leipzig Synagogue, but all of them came from the Spanish-Islamic or North African cultures. According to Künzl, Simonson used the horseshoe-shaped arcades in the Leipzig synagogue for the first time. The Leipzig synagogue was not just one of many big city synagogues, it was a special synagogue because Leipzig, as a trade fair city, also had many Jewish visitors. Because of the role that the synagogue had in the trade fair city of Leipzig, the history of the Leipzig Jews and the reasons for adopting Islamic styles were particularly important (writes also Hammer-Schenk): Only the Saxon Emancipation Act allowed the Leipzig Jews to have one to found their own religious community. Besides Dresden, Leipzig was the only Saxon city that was allowed to have a Jewish religious community. The Emancipation Act lifted the ban on building synagogues in Saxony, so that a large synagogue could also be built in Leipzig. For Simonson - according to Künzl - the Orient was not only the country of origin of the Jews, but also the motherland in the religious sense, since the Jewish religion originated there. Simonson therefore connected the Leipzig synagogue with the Orient. Künzl explains that Simonson wanted to overcome his teacher, Gottfried Semper. While Semper used Arabic lettering ribbons as ornaments for the Dresden synagogue, Semper's student Simonson only used Hebrew lettering ribbons, for example in the frame of the eastern rose window and as ornamental ribbons in the horseshoe arches of the arcades. Semper student Simonson wanted to characterize the synagogue as a Jewish building more than his teacher. The models were the synagogue in Córdoba and the Synagogue of El Tránsito in Toledo, where Hebrew banners frame ornamental fields and window zones. According to Künzl, the synagogue in Leipzig created a type of synagogue that served as a model for many subsequent synagogue buildings.[99]

In 1903/1904 Oscar Schade delivered the designs for the Brody Synagogue , designed in the “neo-Moorish style”,[100] the interior of which (Torah ark, Bimah) was destroyed during the pogrom night of 9/10. November 1938. The Leipzig Stadtbad at Eutritzscher Straße 21 contains a sauna relaxation room designed in the Moorish style. The rooms were designed by Otto Wilhelm Scharenberg and Mathieu Molitor from 1913 to 1915. The Ez Chaim Synagogue, built in 1922 based on designs by the Leipzig architect Gustav Pflaume, was also orientalizing.

- Buildings of Moorish Revival Architecture

-

Relaxroom of the sauna in Stadtbad Leipzig (moorish)

-

Orthodox Brody Synagogue

-

Grand Leipzig Synagogue, designed by Otto Simonson

-

Grand Leipzig Synagogue, designed by Otto Simonson

-

Ez-Chaim-Synagogue, designed by Gustav Pflaume

Neo-Byzantine architecture

[edit]The Leipzig Russian Memorial Church (Russische Gedächtniskirche) was built from 1912 to 1913 in the style of Neo-Byzantine architecture, a style within historicism, based on the model of the Ascension Church in Moscow-Kolomenskoye, based on designs by Vladimir Alexandrovich Pokrovsky (1871–1931) and decorated in the style of Novgorod icon painting.

- Neo-Byzantine Building

-

Leipzig Russian Memorial Church

-

Interior of the church (Novgorod icon painting)

Baroque Revival architecture

[edit]

Steib's Hof at the Dussmann Passage Nikolaistrasse 28-32, Brühl 64-66 is an example of the Baroque Revival architecture in Leipzig. The central axis was particularly elaborately designed: “With its neo-baroque sandstone decoration, the emphasized central axis trumps even the richest town house facades of the 18th century.”[101] The architectural sculptures are allegories of trade and industry. The building was built in 1907 by the Leipzig master builder Felix Steib. Hugo Licht also designed the St. John's Church (Johanniskirche) in this style. Based on designs by Robert Ludwig & Alfred Hülßner, the Café Bauer was completed by Albert Bohm (1853–1933) in 1889/90. The café and restaurant on the ground and upper floors was designed in the neo-baroque style (“in rich baroque forms” [102]).

- Buildings of Baroque Revival architecture

-

Cafe Bauer, Facade

-

Cafe Bauer, Host room in the ground floor

-

Cafe Bauer, Host room in the firstfloor

-

Cafe Bauer, Plan

Swiss chalet style

[edit]

The villa for the consul Friedrich Nachod at Carl-Tauchnitz-Strasse 43, built according to designs by the architect Max Pommer in 1889–1890, was built in the style of eclecticism in a mixture of Swiss chalet style and Renaissance. The roof with its open rafters and the wooden decorative elements attached underneath showed elements of the Swiss chalet style. This was intended to create the impression of country house architecture. Friedrich Nachod was the son of Jacob Nachod (1814–1882), the head of the Israelite Religious Community in Leipzig and co-owner of the bank Knauth, Nachod & Kühne, city councilor in 1888/1889.[103][104][105][106] The building at Hillerstraße 3 was also designed with elements of the Swiss chalet style. It was built for the Secretary of the Chamber of Commerce Dr. Gensel in 1883 based on designs by the architect Heinrich Stöckhardt.[107] The villas in Lößnig are also built in the Swiss chalet style, built in 1890 for the owner Consul Limburger based on designs by the architects Karl Weichardt and Bruno Eelbo.[108]

- Buildings in the Swiss chalet style

-

Villa Schwägrichenstrasse 6

-

Villa Cunnersdorfer Strasse 6

-

Villa Karl-Tauchnitz-Strasse 61

-

Swiss chalet style: Villa Konsul F. Nachod, Floor plan (Max Pommer)

Reform architecture (monumental and material style) and modernism (from 1900)

[edit]

According to Wolfgang Hocquél, Leipzig's reform architecture and Leipzig's Art Nouveau are important - "Around 700 residential buildings... from the turn of the century account for the largest share of the 1,410 monuments in the city of Leipzig."[citation needed]

In terms of urban development,[110] the construction of the new main train station directly adjacent at the old town center was important in 1915, which strengthened Leipzig's position as an international transport hub. In 1927 there were 294 stock corporations in Leipzig with a total capital of approximately 321 million Reichsmarks. Leipzig became an important financial center and the headquarters of the central administrations of many large companies and a transshipment point for goods. The German Credit-Anstalt, the largest German private bank, had its headquarters in Leipzig. The „Meßamt für die Mustermessen in Leipzig“ (“Trade Fair Office for the Sample Fairs in Leipzig”),[111] which was founded in June 1916, and the „Zentralstelle für Interessenten der Leipziger Musterlagermessen“ (“Central Office for those interested in the Leipzig Sample Fairs”) [111] with the industry and business associations behind it successfully called for a revitalization of the Leipzig Trade Fair. The first technical trade fair took place in the city center from 25 to 31 August 1918. The historic old town was completely changed because the new form of trade, the sample fair (Mustermesse), replaced the historic goods fair. Therefore, historically grown city districts were completely destroyed in order to build exhibition centers such as Handelshof or Specks Hof. The change to an industrial city now took place more intensively. In March 1920, the technical fair was organized outside Leipzig and showed machine tools and vehicles there. The exhibition area was constantly increased, from 6,000 square metres (65,000 square feet) in 1920 to 130,000 square metres (1,400,000 square feet) in 1928. Accordingly, goods exported in 1928 amounted to 400 million RM, which corresponded to one sixth of German exports. At the last trade fair before the Great Depression, 34,420 foreigners attended the trade fair. Leipzig maintained its position as a world trading center. After the First World War, the Leipzig trams were taken over by the city and the trams ran into the suburbs. In 1926 came Wiederitzsch, in 1927 Taucha and Engelsdorf, in 1928 Markkleeberg-Ost and Liebertwolkwitz, and in 1931 Thekla and Marienbrunn. In 1929 a general development plan was drawn up. Accordingly, the old town should remain free of high-rise buildings and skyscrapers should be built outside the established historic old town. The inner city ring road was created specifically for this purpose.[112][113] The global depression of 1929 ended Leipzig's economic boom.

Monument to the Battle of the Nations

[edit]

The Monument to the Battle of the Nations (designed by Bruno Schmitz) is an example of the monumental style of reform architecture around 1900.[114] The monument is of "monumental size"[115] and is the "most colossal expression of the Wilhelmine age".[115]

The outsides show rustication. The material effect (in addition to monumentality) was emphasized in reform architecture. The monument was created from regional building material (“local granite porphyry”[114]). It is a synthesis of building and architectural decoration (“fusion of architecture and sculpture”[114]). The Michael relief was created by Christian Behrens. The colossal figures were created by Franz Metzner. They are located in the Hall of Fame and are almost 10 metres (33 feet) tall figures that represent allegories of bravery, strength of faith, people's strength and willingness to sacrifice.[116][117]

- Sculpture work

-

Christian Behrens, Michael relief

-

Franz Metzner,

People's Power (Volkskraft) -

Franz Metzner, Strength of Faith (Glaubensstärke)

-

Franz Metzner,

Bravery (Tapferkeit) -

Franz Metzner, Willingness to sacrifice (Opferbereitschaft)

LVZ building, Volkshaus and ATSB school

[edit]The Leipzig civil engineer and architect Oscar Schade created the designs for the Richard Lipinski House on 19 to 21, Tauchaer Strasse (today Rosa-Luxemburg-Strasse). The house was built in 1910[118] as a publishing building for the “established in 1894”[119] Leipziger Volkszeitung (LVZ).[120][121] There was also a Lenin memorial in the building.[122] The house was designed “in the industrial architecture of Art Nouveau”.[123]

In 1912/1913, Schade was also responsible for designing the residential buildings in the garden suburb of Marienbrunn in the reform architecture style.[124]

In 1904, Schade also provided designs for the Volkshaus[125] with a “ neo-Romanesque ”[126] sandstone facade. During the Kapp Putsch, the building was shot at and set on fire on 19 March 1920. In 1928 the house burned down again. On 2 May 1933, the Sturmabteilung (SA) occupied the Volkshaus.

In 1903/1904 Schade also designed the Brody Synagogue in Leipzig, which was demolished in the pogrom night of 9/10 November 1938.

The Workers' Gymnastics and Sports School (ATSB School) at Fichestrasse 36 in Leipzig was designed in 1924/1925 based on designs by the architect Oscar Schade.[127] On 23 March 1933, the building was occupied by the SA and further school operations were prohibited.

Oscar Schade also rebuilt the Villa Schreiber at Beethovenstrasse 16 in 1936. The villa was built in 1891 in the Italian Renaissance style for the banker Walter Schreiber according to plans by Max Pommer. Schreiber was co-owner of the Leipzig bank Herz Cusel Plaut, which was liquidated as part of the Aryanization in 1933. The banking house was named after Herz Cusel Plaut (1783–1837). The founder was his son Jacob Plaut, after whom the Jacob Plaut Foundation and Leipzig's Jacob-Plaut-Strasse are named.[128] After the Jewish bank was liquidated in 1933, the villa was also confiscated in 1935. The 1936 renovation was designed by the architect Oscar Schade. Very rich double doors from the construction period have been preserved inside.[129][130]

The tomb for the architect Oskar Schade[131] is located in the Leipzig South Cemetery and shows the Masonic badge.

- LVZ building, Volkshaus und ATSB school

-

Former LVZ building, Tauchaer Strasse; today Rosa-Luxemburg-Strasse 19/21 (2013)

-

Volkshaus on Karl-Liebknecht-Strasse (2013)

-

ATSB school on Fichtestrasse (1926)

Art Nouveau houses and Richard Wagner National Monument

[edit]Fritz Drechsler, Raymund Brachmann, Josef Mágr, Paul Möbius, Alfons Berger and Paul Lange are considered representatives of Art Nouveau architecture in Leipzig. Works include the building at Paul-Michael-Strasse 6,[132] the building at Menckestraße 19,[133] the Künstlerhaus , the Riquet House[134] and the Märchenhaus (Fairy Tale House)[135] from 1906/1907.

The Villa Görke at Paul-Michael-Strasse 6,[136] built in 1904 based on designs by Paul Möbius, shows a variety of sculptural shapes and is a “particularly creative variant of Art Nouveau”.[132]

The house at Menckestrasse 19 in Gohlis,[133] built in 1903/1904 based on designs by Alfons Berger, shows a variety of different window formats and is “one of the most interesting examples of Art Nouveau in Leipzig”.[137] In the gable field there are winged, scantily clad elves, which were created using the plaster technique. They carry festoons and flank a cartouche depicting a resting lion.

The Leipzig sculptor Carl Seffner designed Adam with Klinger's facial features in his bronze relief Adam and Eve at the Leipzig Künstlerhaus. The base of the Leipzig Richard Wagner National Monument, created by Max Klinger in 1904, shows themes from the Ring of the Nibelung:

"The front of the block shows three naked Rhinemaidenss - symbolizing music, poetry and drama and thus alluding to Wagner's pursuit of the total work of art. On the left you can see Siegfried, Mime and the slain dragon, on the right the Grail guardian Parsifal and the Grail messenger Kundry.”

— Markus Cottin, 1998[138]

- Leipzig Art Nouveau buildings

-

Fire Station (J. Mágr)

-

Märchenhaus (Fairy Tale House) (R. Brachmann)

-

Künstlerhaus (F. Drechsler)

-

Riquet-Haus, detail (P. Lange)

-

Künstlerhaus club room

-

Richard Wagner National Monument, Siegfried, Mime and the Slain Dragon

-

Richard Wagner National Monument, Grail Guardian Parsifal and the Grail Messenger Kundry

-

Max Klinger as Adam in Adam and Eve by Carl Seffner

-

Möbius House

Shop window facades

[edit]

The Brühl department store building was built in the reform architecture style based on designs by the Leipzig architect Emil Franz Hänsel. Hänsel was a member of the Werkbund and was one of the “most original and therefore probably busiest architects in Leipzig”.[139] Hänsel also built the Dresden Residenz department store and the City of Warsaw commercial building, Brühl 76/78 (probably the site of the former “Gasthaus Zur Stadt Warschau”). The City of Warsaw commercial building had a continuous shop window facade and had the following tenants around 1904: wine wholesaler August Schneider, Vienna & Leipzig; Bernhard Schmidt fur trader; F. A. Seiler cloth goods; Arthur Hermsdorf (fur trading store); Wilhelm Moosdorf Restaurant and Cafe Weissenfelser-Bier-Halle.

Messow & Waldschmidt opened the Brühl GmbH department store on 3 October 1908. The managing directors were Heinrich Hirschfeld and Walter Riess. Paul Messow died in 1909 and the managing director Walter Riess married Messow's daughter Gertrud a year later and became the sole director. Otto Mühlstein and Salomon Sigismund Hirschfeld became the new managing directors. As part of the Aryanization, the previous managing directors Riess, Meiser and Pelz were dismissed in April 1936 and from 12 September 1936 the Jewish property finally became the property of Knoop Co. GmbH.[140]

Leopold Stentzler also built the Messehaus Stentzlers Hof buildings at Petersstrasse 39 to 41[141] and the Messehaus Dresdner Hof at Neumarkt 21 to 27 from 1914 to 1916. Messehaus means, that these houses were used as exhibition centers in the context of the Leipzig Trade Fair. The Messehaus Dresdner Hof was built for the entrepreneur Richard Pudor. Stentzler's trade fair palace is comparable to Behrens' work: "In terms of design, Leopold Stentzler's trade fair palace Dresdner Hof is close to the design of contemporary buildings by Peter Behrens, one of the leading German architects of the time, who demonstrated a similar traditional objectivity in the festival hall of the Cologne Werkbund exhibition in 1914."[142] The Mädlerhaus Leipzig and the F. Lindner commercial building were also built in the style of reform architecture based on designs by the Leipzig architect Leopold Stentzler. The Mädlerhaus Leipzig featured a continuous shop window facade.

Krochhochhaus and Europahaus

[edit]The Krochhochhaus on Augustusplatz is the first high-rise building in Leipzig and also an example of “ classic modernism ”. The building,[143] which was built in 1927/1928 based on designs by German Bestelmeyer for the German-Jewish banker Hans Kroch, met with both rejection and approval. Critics said that the architectural decoration was inappropriate for a private, Jewish bank: “The proposed roof figures, which are supposed to drum on a fairly large bell in order to elicit the note E several times during the day, are also impossible... After all, the Kroch private bank is not a “city hall, not a public symbol that could be given a privileged effect”.[144] Others also saw the connections to Italy. The model for the Kroch high-rise was the Torre dell'Orologio clock tower in Venice, built between 1496 and 1499, with St. Mark's lions: “The building quotes were applauded in Leipzig, certainly also because of the centuries-old connections to the Italian trading cities and their culture... The result also convinced them, who had feared that the tower house would visually devalue the 'most beautiful square in Europe', as they confidently said at the time."[145] The second high-rise building, the Europahaus, designed by Otto Paul Burghardt (1875–1959), was built in 1928/1929 as a counterweight to the Kroch High Rise on Augustusplatz.

- Kroch High Rise and Europahaus – classic modernism

-

Kroch High Rise (Krochhochhaus) (2011)

-

St. Mark's lions on the Krochhochhaus based on the model of the Torre dell'Orologio in Venice (2010)

-

Europahaus (2007)

Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (German National Library) and Sculptures

[edit]The German National Library building at Deutscher Platz 1 was built from 1914 to 1916 based on designs by Oskar Pusch.

Above the building's main entrance are busts of Otto von Bismarck, Johannes Gutenberg and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the latter signed by the Dresden sculptor Fritz Kretzschmar. On the main facade there are seven larger-than-life sculptures that stand on consoles above the ground floor area. These figures by Adolf Lehnert and Felix Pfeifer are allegories for technology, art, justice, philosophy, theology and medicine, flanked on the sides by the figures of the writer and the reader by Johannes Hartmann with the coats of arms of the city of Leipzig (left) and the Börsenverein (right). The following inscriptions can be read in German language above the main entrance:

Körper und Stimme leiht die Schrift dem stummen Gedanken, durch der Jahrhunderte Strom trägt ihn das redende Blatt.

— Writing lends body and voice to the silent thought, through the centuries-old stream the speaking paper carries it.

and

Freie Statt für freies Wort, freier Forschung sicherer Port, reiner Wahrheit Schutz und Hort.

— Free place for free speech, free research a safe haven, pure truth protection and refuge.

The building rejects conventional historicism in favor of reform architecture: “This architecture does not follow a specific stylistic model; rather, the different details are handled completely freely in the sense of adaptations and put together to form a facade design that sets itself apart from models of all kinds.”[146]

- German National Library (Deutsche Nationalbibliothek)

-

Entrance to the German National Library in Leipzig

-

Allegories for philosophy, theology and medicine

Petershof exhibition center and sculptures (until 1938)

[edit]The Messehaus Petershof (trade fair building Petershof) at Petersstrasse 20 is an example of “classic modernism”[147] and was built for the publisher Josef Mathias Petersmann[148] based on designs by Alfred Liebig: “ Liebig reduced the structure of the main front with boldly protruding window frames traditional facade architecture in the simplest forms, but avoided the hallmarks of modernity - ribbon windows and insubstantial external walls. Instead, the barrenness is refined with high-quality natural stone (Cannstatter Travertine).”[149]

The Leipzig artist Johannes Göldel (1891–after 1946) created the seven larger-than-life sculptures that are located on consoles above the ground floor area. These are people whose activities are directly linked to the history of the building.

The figures, starting from the left, represent: building director Ludwig Fraustadt, commercial councilor Felix Geissler, banker Hans Kroch, who obtained the building loan, mayor Karl Rothe, who was committed to the construction, trade fair director Raimund Köhler, architect of the house Alfred Liebig and trade fair board member Edgar Hoffmann. Through the attached attributes, the figures also symbolize music, decorative arts, trade, drama, trade fairs, architecture and industry. Since Hans Kroch was Jewish, the statues were removed during the November pogroms in 1938 at the “instance of the National Socialists”.[147] In 1994, the Leipzig sculptor Markus Brille created true-to-original copies, which were installed in the old location on the facade in 1995. The facade is a listed building.[150]

- Messehaus Petershof (Petershof exhibition center)

-

Petershof with the seven sculptures 1929

-

„Petershof“ exhibition center 1938

-

Petershof facade 2014

Ceremony hall at the New Israelite Cemetery (until 1939)

[edit]An example of a modern sacred building[151] in Leipzig was the celebration hall in the new Israelite cemetery, built from 1926 to 1928 (designs by Wilhelm Haller ). The domed building showed “oriental architectural decoration that the architect had gotten to know on various trips.”[152] This orientalizing architectural decoration, including the stalactite vault or muqarnas modeled on the Moorish Naṣrid palaces in the domed building, was linked to the expressionist tendencies of the 1920s. The inscription above the entrance read: Hebrew: כִּי-עַזָּה כַמָּוֶת אַהֲבָה (English: love is as strong as death). The building fell victim to Kristallnacht:

On 9 November 1938, the outbuildings of the celebration hall fell victim to the arson attacks on Kristallnacht. Although the domed hall remained almost undestroyed and could not be addressed as an actual fire ruin,[153] as the city reported to the Saxon Ministry of the Interior in a report dated 15 November 1938, the building police office asked the community to demolish all buildings just two days after the fire, as they represent a danger[154] and deface the cityscape.[154] Only a few weeks after the removal of the outbuildings, the community managed to postpone the demolition of the intact domed hall. At the end of the year, the city administration, in the person of the building police director Franz Gerlach, the city building officer Werner Liebig and the mayor Rudolf Haake, increased the effort to demolish it on their own initiative, using various legal pretexts and legal tricks. On 24 February 1939 the hall was blown up.[152]

- Ceremony hall at the New Israelite Cemetery

-

Former celebration hall in the New Israelite Cemetery

-

New celebration hall in the New Israelite Cemetery with the same inscription as the old, blown-up celebration hall

Leipzig Zoo: Bear Castle and Jason Monument

[edit]Carl James Bühring built a textile exhibition center at Härtelstrasse 16-18 from 1922 to 1924. He also designed the “Bear Castle” with six 10 metres (33 feet) tall towers in the Leipzig Zoo in the neoclassical style. The bear castle, built between 1929 and 1930, stands at the end of a path axis. Path axes with decorative places structure the garden.

At the beginning of the main route to the elephant enclosure is the Jason monument. The bronze group[155] is part of the development plan by Carl James Bühring and Johannes Gebbing from 1927, when the zoo was expanded from 7 hectares (17 acres) to 12.5 hectares (31 acres). The Jason group by the Berlin sculptor Walter Lenck (1873–1952),[156] which received the Grand Prix at the International Exhibition in Buenos Aires, was acquired in 1911 for the Zoological Garden in Berlin. The Berlin sculptor also created, among other things, a 43.5 centimetres (17.1 inches) tall bronze model of a naked archer. The casting was carried out by the bronze foundry Martin & Piltzing Berlin. The Leipzig Zoo's Jason monument has been there since 1928 and previously stood in the Berlin Zoo for 17 years. The group of figures at the Leipzig Zoo is 4 metres (13 feet) long and 3.50 metres (11.5 feet) wide.[157]

Max Klinger's bronze “Athlete” is the Leipzig Zoo's “most important visual artistic work” and was installed to the east of the pachyderm house.[156]

-

Jason Monument by W. Levy or W. Lenck

-

Athlete by M. Klinger

-

Leipzig Härtelstraße 16–18, Textilmessehaus (Textile Trade Fair House)

-

Bärenburg (Bear Castle)

Great Depression and Neo-Neoclassicism (from the 1930s)

[edit]After the National Socialists came to power, Nazi neoclassicism determined Leipzig architecture: “After 1933, the repressive policies of the Nazi regime also took control of exhibition architecture.”[158] Jewish architects had their professional licenses revoked; the German-Jewish architect Wilhelm Haller was able to escape. In housing construction, the Leipzig architects “very quickly became attuned to the traditional building forms and to the blood and soil architecture of small settlements [...] The representative buildings of the new rulers gained the upper hand in the field of urban planning and in public buildings in the demands for axiality.”[159] National Socialist architecture was particularly characterized by the timeless and elaborate building materials, including dimension stone, marble, Muschelkalk, travertine and granite. Porphyry has been used in Leipzig since 1951 in the architectural style of socialist neoclassicism.

Entrance building on Prager Strasse to the exhibition hall

[edit]The Great Depression, beginning with the Wall Street Crash in October 1929, had ended further construction of the Leipzig Trade Fair in the spring of 1930. According to Peter Leonhardt, it took seven years before the further construction of the Leipzig Trade Fair could be continued: “It was only in 1937 that the project was taken up again under the changed conditions of the Nazi dictatorship and shows, as in a few places, the breaks in 1933 in architectural history.”[160] Curt Schiemichen had now become a “kind of general architect of the Leipzig Trade Fair”.[160] Instead of using transparent glazing, Schiemichen now worked with stone cladding, for example in the entrance building on Prager Strasse to the exhibition hall (Technical Trade Fair, new Hall 20 - later Hall 2).[160] During recent demolition work at the old technical fair site in Leipzig, the listed stone entrance portal of Hall 2 remained standing.

Richard Wagner Hain

[edit]

In 1932, Emil Hipp won the city of Leipzig 's competition for a Richard Wagner monument in the style of neoclassicism, which "enjoyed the special support of the Nazi leadership".[161] On 6 March 1934, the foundation stone for the " Richard-Wagner-Hain " was laid by Adolf Hitler in the presence of Mayor Carl Friedrich Goerdeler. According to Markus Cottin, a “monument complex the size of the Dresden Zwinger”[161] was to be built on the east bank of the newly created Elster flood basin, in the eastern part of the Palmengarten Park.

According to Wolfgang Hocquél, Emil Hipp's reliefs were a neoclassical work with "an imaginative, allegorical sculptural work of timeless aesthetics".[162] The neoclassical sculptor planned 250 tons of marble. By 1944, the execution of the order was almost complete. Hipp's Leipzig Wagner monument had four sides, with each side being 10 metres (33 feet) long and approximately 3 metres (9.8 feet) high. Resting on a 1 metre (3.3 feet) high base, the monument was 4 metres (13 feet) tall in total. The four reliefs dealt with destiny, myth, redemption and bacchanal. For the 2.80 metres (9.2 feet) tall and 430 metres (1,410 feet) long wall surrounding the monument square, the sculptor created another 19 marble reliefs with scenes from Wagner's musical dramas, a Siegfried figure and a Rhinemaidens fountain, including the relief Hagen kills Siegfried. Leipzig paid for the 3.6 million Reichsmark work until it was completed. In the post-war period, Hipp's sculptural work was no longer up to date during the GDR era and the monument was sold. A doctor from Bavaria purchased the main reliefs and placed them on the inside of his courtyard wall.[163] During GDR times, the Richard-Wagner-Hain was forgotten. The supporting concrete block for the main reliefs was demolished, floor slabs were removed, and parts were built over and changed.

- Hipp – Neo-neoclassicism

-

Remains of the Richard Wagner monument in Leipzig (today in Bayreuth): Senta and maids in the “Flying Dutchman” spinning room

-

Note: Parts of a Richard Wagner monument that was planned by the city in 1932, designed and executed by Prof. Emil Hipp, but no longer erected

-

Remains of the Richard Wagner monument in Leipzig (today in Bayreuth): Hagen kills Siegfried “Twilight of the Gods”

Merkurhaus instead of Polich department store

[edit]

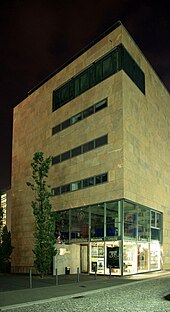

During the Nazi era, C&A benefited from the Aryanization of Jewish property, promoted NSDAP membership among senior employees and gave expensive gifts to important Nazi politicians.[164] The Polich Jewish department store, acquired by C&A Germany as part of the Aryanization, was demolished and in its place in 1937 the Merkurhaus in the New Objectivity style by Karl Fezer (1900–1984), who oversaw the conversion and new construction of C&A Germany's commercial buildings, was built.[165] The new building is an office and commercial building with three street facades, designed as a six-story reinforced concrete frame structure with elaborate shell limestone cladding. With its two oriel window-like porches, the building follows the Leipzig “bay window tradition”[citation needed] from the Baroque and Renaissance periods:

"The strict horizontal structure through the row of windows as well as the strong cornices determine the overall impression. The oriel window-like porches on Markgrafenstrasse and Schloßgasse provide an effective contrast. In keeping with its original purpose as a textile department store, the house was symbolically placed under the protection of the trade god Mercury, to whom a sculpture above the main entrance was once dedicated. The noble effect of the shell limestone for the facade cladding as well as the clever adaptation to the irregular site give the building a special aesthetic appeal even without elaborate decorative shapes [...]."

— Wolfgang Hocquél, 1990[166]