Vanadyl sulfate

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Oxovanadium(2+) sulfate

| |

| Other names

Basic vanadium(IV) sulfate

Vanadium(IV) oxide sulfate Vanadium(IV) oxysulfate | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.044.214 |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| Properties | |

| H10O10SV | |

| Molar mass | 253.07 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Blue solid |

| Melting point | 105 °C (221 °F; 378 K) decomposes |

| Soluble | |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards

|

Irritant |

| Flash point | Non-flammble |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Vanadyl chloride Vanadyl nitrate |

Other cations

|

Vanadium(III) sulfate |

Related compounds

|

Vanadyl acetylacetonate |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

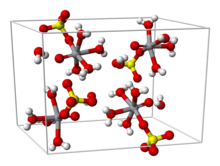

Vanadyl(IV) sulfate describes a collection of inorganic compounds of vanadium with the formula, VOSO4(H2O)x where 0 ≤ x ≤ 6. The pentahydrate is common. This hygroscopic blue solid is one of the most common sources of vanadium in the laboratory, reflecting its high stability. It features the vanadyl ion, VO2+, which has been called the "most stable diatomic ion".[1]

Vanadyl sulfate is an intermediate in the extraction of vanadium from petroleum residues, one commercial source of vanadium.[2]

Synthesis, structure, and reactions

[edit]Vanadyl sulfate is most commonly obtained by reduction of vanadium pentoxide with sulfur dioxide:

- V2O5 + 7 H2O + SO2 + H2SO4 → 2 [V(O)(H2O)4]SO4

From aqueous solution, the salt crystallizes as the pentahydrate, the fifth water is not bound to the metal in the solid. Viewed as a coordination complex, the ion is octahedral, with oxo, four equatorial water ligands, and a monodentate sulfate.[1][3] The trihydrate has also been examined by crystallography.[4] A hexahydrate exists below 13.6 °C (286.8 K).[5] Two polymorphs of anhydrous VOSO4 are known.[6]

The V=O bond distance is 160 pm, about 50 pm shorter than the V–OH2 bonds. In solution, the sulfate ion dissociates rapidly.

Being widely available, vanadyl sulfate is a common precursor to other vanadyl derivatives, such as vanadyl acetylacetonate:[7]

- [V(O)(H2O)4]SO4 + 2 C5H8O2 + Na2CO3 → [V(O)(C5H7O2)2] + Na2SO4 + 5 H2O + CO2

In acidic solution, oxidation of vanadyl sulfate gives yellow-coloured vanadyl(V) derivatives. Reduction, e.g. by zinc, gives vanadium(III) and vanadium(II) derivatives, which are characteristically green and violet, respectively.

Occurrence in nature

[edit]Like most water-soluble sulfates, vanadyl sulfate is only rarely found in nature. Anhydrous form is pauflerite,[8] a mineral of fumarolic origin. Hydrated forms, also rare, include hexahydrate (stanleyite), pentahydrates (minasragrite, orthominasragrite,[9] and anorthominasragrite) and trihydrate - bobjonesite.[10]

Medical research

[edit]Vanadyl sulfate is a component of food supplements and experimental drugs. Vanadyl sulfate exhibits insulin-like effects.[11]

Vanadyl sulfate has been extensively studied in the field of diabetes research as a potential means of increasing insulin sensitivity. No evidence indicates that oral vanadium supplementation improves glycaemic control.[12][13] Treatment with vanadium often results in gastrointestinal side-effects, primarily diarrhea.

Vanadyl sulfate is also marketed as a health supplement, often for bodybuilding. Deficiencies in vanadium result in reduced growth in rats.[14] Its effectiveness for bodybuilding has not been proven; some evidence suggests that athletes who take it are merely experiencing a placebo effect.[15]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1984). Chemistry of the Elements. Oxford: Pergamon Press. p. 1157. ISBN 978-0-08-022057-4.

- ^ Günter Bauer; Volker Güther; Hans Hess; Andreas Otto; Oskar Roidl; Heinz Roller; Siegfried Sattelberger (2005). "Vanadium and Vanadium Compounds". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a27_367. ISBN 3-527-30673-0.

- ^ Tachez, M.; Theobald, F.R. (1980). "Structure du Sulfate de Vanadyle Pentahydrate VO(H2O)5SO4 beta (variete orthorhombique)". Acta Crystallographica B. B36 (8): 1757–p1761. Bibcode:1980AcCrB..36.1757T. doi:10.1107/S0567740880007170.

- ^ Tachez, M.; Theobald, F. R. (1980). "Liaisons hydrogène dans les cristaux de sulfate de vanadyle trihydrate VOSO4(H2O)3: Comparaison structurale de quatre sulfates de vanadyle hydrate". Acta Crystallographica B. 36 (12): 2873–2880. Bibcode:1980AcCrB..36.2873T. doi:10.1107/S056774088001045X.

- ^ M. Tachez, F. Theobald, G. Trouillot. Crystal data for vanadyl sulphate hexahydrate VOSO4.6H2O. J. Appl. Crystallogr. (1976). 9, 246

- ^ Boghosian, S.; Eriksen, K.M.; Fehrmann, R.; Nielsen, K. (1995). "Synthesis, Crystal Structure Redetermination and Vibrational Spectra of beta- VOSO4". Acta Chemica Scandinavica. 49: 703–708. doi:10.3891/acta.chem.scand.49-0703.Longo, J. M.; Arnott, R. J. (1970). "Structure and magnetic properties of VOSO4". Journal of Solid State Chemistry. 1 (3–4): 394–p398. Bibcode:1970JSSCh...1..394L. doi:10.1016/0022-4596(70)90121-0.

- ^ Bryant, Burl E.; Fernelius, W. Conard (1957), "Vanadium(IV) Oxy(acetylacetonate)", Inorganic Syntheses, vol. 5, pp. 113–16, doi:10.1002/9780470132364.ch30, ISBN 978-0-470-13236-4

- ^ Krivovichev, S. V.; Vergasova, L. P.; Britvin, S. N.; Filatov, S. K.; Kahlenberg, V.; Ananiev, V. V. (1 August 2007). "Pauflerite, -VO(SO4), a New Mineral Species from the Tolbachik Volcano, Kamchatka Peninsula, Russia". The Canadian Mineralogist. 45 (4): 921–927. Bibcode:2007CaMin..45..921K. doi:10.2113/gscanmin.45.4.921.

- ^ Hawthorne, F. C.; Schindler, M.; Grice, J. D.; Haynes, P. (1 October 2001). "Orthominasragrite, V4+O(SO4)(H2O)5, A New Mineral Species from Temple Mountain, Emery County, Utah, U.A.A.". The Canadian Mineralogist. 39 (5): 1325–1331. Bibcode:2001CaMin..39.1325H. doi:10.2113/gscanmin.39.5.1325.

- ^ Schindler, M.; Hawthorne, F. C.; Huminicki, D. M.C.; Haynes, P.; Grice, J. D.; Evans, H. T. (1 February 2003). "Bobjonesite, V4+ O (So4) (H2O)3, A New Mineral Species from Temple Mountain, Emery County, Utah, U.s.a.". The Canadian Mineralogist. 41 (1): 83–90. Bibcode:2003CaMin..41...83S. doi:10.2113/gscanmin.41.1.83.

- ^ Crans, D. C.; Trujillo, A. M.; Pharazyn, P. S.; Cohen, M. D. (2011). "How environment affects drug activity: Localization, compartmentalization and reactions of a vanadium insulin-enhancing compound, dipicolinatooxovanadium(V)". Coord. Chem. Rev. 255 (19–20): 2178–2192. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.032.

- ^ Yeh, Gloria Y.; Eisenberg, David M.; Kaptchuk, Ted J.; Phillips, Russell S. (2003). "Systematic Review of Herbs and Dietary Supplements for Glycemic Control in Diabetes". Diabetes Care. 26 (4): 1277–1294. doi:10.2337/diacare.26.4.1277. PMID 12663610.

- ^ Smith, D.M.; Pickering, R.M.; Lewith, G.T. (31 January 2008). "A systematic review of vanadium oral supplements for glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus". QJM. 101 (5): 351–358. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcn003. PMID 18319296.

- ^ Schwarz, Klaus; Milne, David B. (1971). "Growth Effects of Vanadium in the Rat". Science. 174 (4007): 426–428. Bibcode:1971Sci...174..426S. doi:10.1126/science.174.4007.426. JSTOR 1731776. PMID 5112000. S2CID 24362265.

- ^ Talbott, Shawn M.; Hughes, Kerry (2007). "Vanadium". The Health Professional's Guide to Dietary Supplements. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 419–422. ISBN 978-0-7817-4672-4.