User:PizzaKing13/sandbox

Salvadoran Civil War

[edit]

| Salvadoran Civil War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Central American crisis and the Cold War | |||||||

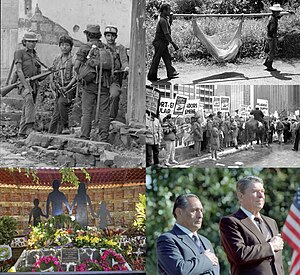

Clockwise from top right: two Salvadorans carrying a casualty of war, an anti-war protest in Chicago, Salvadoran president José Napoleón Duarte and U.S. president Ronald Reagan, a memorial to the El Mozote massacre, ERP fighters in Perquín | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 10,360+ killed | 12,274–20,000 killed | ||||||

|

65,161+ civilians killed 5,292+ disappeared 550,000 internally displaced 500,000 refugees in other countries | |||||||

The Salvadoran Civil War (Spanish: guerra civil de El Salvador) was a twelve-year-long civil war fought in El Salvador between the Salvadoran government and the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), a coalition of left-wing rebel groups. The government was supported by the United States, while the FMLN received backing from Cuba and the Soviet Union.

Throughout the 1970s, repression by the Salvadoran military government against the Salvadoran lower classes led to social unrest in the country and the formation of various left-wing militant groups which sought to topple the military government. The civil war began on 15 October 1979 after a coup d'état led by junior military officers overthrew military president Carlos Humberto Romero and established the Revolutionary Government Junta (JRG) to govern the country. A subsequent increase in repression and the assassinations of various political and religious figures led to five left-wing militant groups forming the FMLN in October 1980. In January 1981, the FMLN launched a military offensive against the JRG and gained control of several rural areas of El Salvador.

Background

[edit]Political situation

[edit]Since the 1931 coup d'état which overthrew democratically elected president Arturo Araujo, El Salvador had been governed by a series of military dictatorships.[3] In January 1932, President and Brigadier General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez crushed an uprising led by the Communist Party of El Salvador following the cancelation of the 1932 legislative and municipal elections.[4] The ensuing government mass killings, known in El Salvador as La Matanza, resulted in the deaths of between 10,000 to 40,000 peasants and indigenous people.[5] Martínez was the longest serving president in Salvadoran history, remaining in office from 1931 until his resignation in 1944.[6][a] Martínez's military colleagues—Brigadier General Andrés Ignacio Menéndez, Colonel Osmín Aguirre y Salinas, and Brigadier General Salvador Castaneda Castro—continued Martínez's government after his resignation in short, consecutive presidential terms.[9][10]

The Majors' Coup of December 1948 overthrew Castaneda and established the Revolutionary Council of Government (a military junta), ending the last remnants of Martínez's government.[10] From 1950 to 1960, Major Óscar Osorio and Lieutenant Colonel José María Lemus of the Revolutionary Party of Democratic Unification held the presidency in two consecutive presidential terms until Lemus was overthrown in October 1960 by senior and junior military officers who established the Junta of Government.[11] This reformist government—which promised to implement economic, political, and social reforms–was short-lived, however; a counter-coup in January 1961 overthrew the Junta of Government and established the Civic-Military Directory.[12]

The leaders of the 1961 counter-coup established the military-run right-wing National Conciliation Party (PCN),[13] and in the 1962 presidential election, Lieutenant Colonel Julio Adalberto Rivera Carballo was elected as president of El Salvador unopposed.[14] Although the 1961 coup sought to undermine the reforms proposed by the Junta of Government, the Civic-Military Directory and subsequent PCN-led government eventually promised to carry out the promised economic, political, and social reforms.[14] Under the PCN's government, El Salvador held presidential and legislative elections in which opposition parties were allowed to participate.[15] During the PCN's rule of El Salvador, the center-left Christian Democratic Party (PDC) was the largest opposition party.[16]

Economic inequality

[edit]For most of Salvadoran history, the majority of land had been controlled by a few wealthy landowners commonly referred to as the "Fourteen Families". By the 1970s, these landowners owned most of the country's coffee, sugar, and cotton plantations, accounting for over 60 percent of El Salvador's land.[17] Meanwhile, almost half of El Salvador's population owned no land.[18]

During the 1960s, the Salvadoran government allowed workers and peasants to organize trade unions and other workers' organizations.[18]

Prelude

[edit]Football War

[edit]1972 and 1977 presidential elections

[edit]Political scientist Dieter Nohlen identified both the 1972 and 1977 presidential elections as having been marred by "massive electoral fraud".[19]

Presidency of Carlos Humberto Romero

[edit]

Order of battle

[edit]Salvadoran government

[edit]

In 1979, the Salvadoran military implemented a mandatory 18-month (later 24-month) conscription period for all 18 and 19-year-olds, after which, the conscripts could continue military service or be reverted to reservists.[20]

The following is the chain of command of the Salvadoran security forces at the start of the civil war in 1979.[21][22]

President of El Salvador (Commander-in-Chief)

President of El Salvador (Commander-in-Chief)

- Minister of Defense and Public Security

- Vice Minister of Defense

- Joint General Staff

Salvadoran Army

Salvadoran Army

- 1st Infantry Brigade

- 2nd Infantry Brigade

- 3rd Infantry Brigade

- Frontier Detachment 1

- Frontier Detachment 2

- Frontier Detachment 3

- Frontier Detachment 4

- Frontier Detachment 5

- Frontier Detachment 6

- Frontier Detachment 7

- Recruit Instruction Center

- Engineer Instruction Center

- Commando Instruction Center

- Artillery Brigade

- Cavalry Regiment

Salvadoran Navy

Salvadoran Navy Salvadoran Air Force

Salvadoran Air Force

- Joint General Staff

- Public Security Forces Joint Staff

- Vice Minister of Defense

- Minister of Defense and Public Security

Rebel groups

[edit]

The Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front was named after Farabundo Martí, a leader of the Communist Party of El Salvador who was executed by the Salvadoran government shortly after the events of La Matanza in 1932.[23]

The FMLN was composed of five major left-wing militant groups: the Communist Party of El Salvador (PCES), the Farabundo Martí Popular Liberation Forces (FPL), the National Resistance Armed Forces (FARN), the People's Revolutionary Army (ERP), and the Revolutionary Party of the Central American Workers (PRTC). Each of these military groups also had an associated political wing: the PCES' National Democratic Union (UDN), the FPL's People's Revolutionary Bloc (BPR), FARN's Unified Popular Action Front (FAPU), the ERP's 28 February Popular Leagues (LP-28), and the PRTC's People's Liberation Movement (MLP).[24]

The Revolutionary Democratic Front (FDR) served as the political and diplomatic branch of the FMLN.[25]

The following is the chain of command of the FMLN during the civil war.[24]

Course of civil war

[edit]1979 coup d'état

[edit]Assassination of Óscar Romero

[edit]Final offensive of 1981

[edit]General offensive of 1982

[edit]

By 1985, 171 of El Salvador's then-262 municipalities had been directly affected by the civil war.[26]

Final offensive of 1989

[edit]Foreign involvement

[edit]United States

[edit]

Soviet Union

[edit]Cuba

[edit]Other involvement

[edit]Casualties

[edit]Supporters of the Salvadoran government claimed that a maximum of 20,000 people were killed during the civil war, while some activists claimed that more than 100,000 were killed. According to the Truth Commission for El Salvador, around 75,000 people were killed. In 2019, Demographic Research estimated that 71,629 were killed.[27]

According to the Truth Commission for El Salvador, the Commission for Human Rights in El Salvador, and the Catholic Archdiocese of San Salvador, the period between 1981 and 1983 was the most violent era of the civil war.[26]

Human rights abuses

[edit]Massacres

[edit]

Death squads

[edit]Peace efforts

[edit]Anti-war protests

[edit]

Peace negotiations

[edit]Chapultepec Peace Accords

[edit]

Aftermath

[edit]Political ramifications

[edit]ARENA and the FMLN held an effective duopoly in Salvadoran politics until the 2019 presidential election where Nayib Bukele of the Grand Alliance for National Unity defeated both parties' candidates.[28][29][30]

Military and police reform

[edit]Refugees and Salvadoran diaspora

[edit]

Truth Commission for El Salvador

[edit]

Post-war litigation

[edit]Amnesty law

[edit]On 11 July 2016, the Supreme Court of Justice ruled the law to be unconstitutional for obstructing El Salvador's constitutional obligation to investigate crimes against humanity.[31]

Prosecution of war criminals

[edit]Legacy

[edit]Public perception in El Salvador

[edit]In 2017, The Economist described the 25th anniversary of the peace accords as an "unhappy anniversary", reporting that celebrations to commemorate the anniversary were "emptier than normal" in comparison to other public events.[32]

Commemoration

[edit]

In January 2017, Cerén inaugurated the Monument to the Reconciliation to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the peace accords. The monument was demolished in January 2024 by the Ministry of Public Works to make way for a park.[33]

On 16 December 2020, Bukele stated that 16 January would no longer commemorate the signing of the peace accords but rather commemorate those who were killed or disappeared during the civil war. He further called the peace accords a "farce". Shortly after Bukele's remarks, 107 academic wrote an open letter to his government calling upon it to "honor the memory of the victims of the armed conflict, strengthening the positive legacy of the Peace Accords".[34]

In popular culture

[edit]Several films and documentaries have been made which cover events of the Salvadoran Civil War.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Maximiliano Hernández Martínez was president of El Salvador from 1931 to 1944, however, he briefly left office from 1934 to 1935 in order to run for election in the 1935 presidential election. Minister of Defense Andrés Ignacio Menéndez served as provisional president during this period.[7][8]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ McClintock 1985, pp. 344–345.

- ^ a b Bosch 1999, p. 112.

- ^ Haggerty 1990, p. 33.

- ^ McClintock 1985, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Tulchin & Bland 1992, p. 167.

- ^ Haggerty 1990, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Luna 1969, pp. 50 & 97.

- ^ Ching 1997, p. 501.

- ^ Bosch 1999, p. 8.

- ^ a b McClintock 1985, pp. 130–132.

- ^ Haggerty 1990, pp. 18–21.

- ^ McClintock 1985, pp. 137 & 149.

- ^ Haggerty 1990, pp. 21 & 169–170.

- ^ a b McClintock 1985, p. 149.

- ^ Nohlen 2005, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Haggerty 1990, pp. 21 & 164.

- ^ Ram 1983, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Hoover Green & Ball 2019, p. 783.

- ^ Nohlen 2005, pp. 288–289.

- ^ Haggerty 1990, pp. 209–210.

- ^ Haggerty 1990, p. 210.

- ^ Bosch 1999, p. 21.

- ^ Lindo Fuentes, Ching & Lara Martínez 2007, pp. 184 & 242.

- ^ a b Central Intelligence Agency 1984, p. 9.

- ^ Ram 1983, p. 4.

- ^ a b Acosta et al. 2023, p. 206.

- ^ Hoover Green & Ball 2019, pp. 781–782.

- ^ Gonzalez 2019.

- ^ Harrison 2022.

- ^ Meléndez-Sánchez 2023, pp. 16 & 18.

- ^ DeLugan 2016.

- ^ The Economist 2017.

- ^ Beltrán Luna 2024.

- ^ Luz Nóchez 2021.

Bibliography

[edit]Books

[edit]- Bernal Ramírez, Luis Guillermo & Quijano de Batres, Ana Elia, eds. (2009). Historia 2 El Salvador [History 2 El Salvador] (PDF). Historia El Salvador (in Spanish). El Salvador: Ministry of Education. ISBN 9789992363683. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- Bosch, Brian J. (1999). The Salvadoran Officer Corps and the Final Offensive of 1981. Jefferson, North Carolina; London: McFarland & Company Incorporated Publishers. ISBN 0786406127. LCCN 99-26678. OCLC 41662421. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- Ching, Erik K. (1997). From Clientelism to Militarism: The State, Politics and Authoritarianism in El Salvador, 1840–1940. Santa Barbara, California: University of California, Santa Barbara. OCLC 39326756. ProQuest 304330235. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- Haggerty, Richard A., ed. (1990). El Salvador: A Country Study (2nd ed.). Washington, D.C., United States: Federal Research Division. ISBN 9780525560371. LCCN 89048948. OCLC 1044677008. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- Lindo Fuentes, Héctor; Ching, Erik & Lara Martínez, Rafael A. (2007). Remembering a Massacre in El Salvador: The Insurrection of 1932, Roque Dalton, and the Politics of Historical Memory. Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 9780826336040. OCLC 122424174. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- McClintock, Michael (1985). The American Connection: State Terror and Popular Resistance in El Salvador. Vol. 1. London, United Kingdom: Zed Books. ISBN 9780862322403. OCLC 1145770950. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- Nohlen, Dieter (2005). Elections in the Americas A Data Handbook Volume 1: North America, Central America, and the Caribbean. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. pp. 270–299. ISBN 9780191557934. OCLC 58051010. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- Tulchin, Joseph S. & Bland, Gary, eds. (1992). Is There a Transition to Democracy in El Salvador?. L. Rienner Publishers. doi:10.1515/9781685854638. ISBN 9781555873103. OCLC 1378174458. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

Journals

[edit]- Acosta, Pablo; Baez, Javier E.; Caruso, Germán & Carcach, Carlos (2023). "The Scars of Civil War: The Long-Term Welfare Effects of the Salvadoran Armed Conflict". Economía. 22 (1). LSE Press: 203–217. ISSN 1529-7470. JSTOR 27302241. OCLC 10243911663.

- Hoover Green, Amelia (2017). "Armed Group Institutions and Combatant Socialization: Evidence from El Salvador". Journal of Peace Research. 54 (5). Sage Publishing: 687–700. doi:10.1177/0022343317715300. ISSN 0022-3433. JSTOR 48590496. OCLC 7126356262.

- Hoover Green, Amelia & Ball, Patrick (2019). "Civilian Killings and Disappearances During Civil War in El Salvador (1980–1992)" (PDF). Demographic Research. 41 (27). Max Planck Society: 781–814. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2019.41.27. ISSN 1435-9871. JSTOR 26850667. OCLC 8512899425. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- Luna, David (1969). "Analisis de una Dictadura Fascista Latinoamericana, Maximiliano Hernández Martínez, 1931–1944" [Analysis of a Latin American Fascist Dictatorship, Maximiliano Hernández Martínez, 1931–1944]. Revista la Universidad (in Spanish) (5). San Salvador, El Salvador: University of El Salvador: 41–130. ISSN 0041-8242. OCLC 493370684. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- Ram, Susan (1983). "El Salvador: Perspectives on a Revolutionary Civil War". Social Scientist. 11 (8). Social Scientist: 3–38. doi:10.2307/3517048. ISSN 0970-0293. JSTOR 3517048. OCLC 5546270152.

Newspapers

[edit]Web sources

[edit]- Beltrán Luna, Jorge (3 January 2024). "Obras Públicas Demuele Monumento a la Reconciliación Nacional" [Ministry of Public Works Demolished Monument to the National Reconciliation]. El Diario de Hoy (in Spanish). Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- DeLugan, Robin Maria (20 July 2016). "Amnesty No More". North American Congress on Latin America. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- "El Salvador: Significant Political Actors and Their Interaction" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency. April 1984. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

- Gonzalez, Elizabeth (4 February 2019). "Bukele Breaks El Salvador's Two-Party Hold on Power". Americas Society. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- Harrison, Chase (31 May 2022). "In El Salvador, a Chastened Opposition Looks to Find Its Way". Americas Quarterly. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- Luz Nóchez, María (19 January 2021). "Letter from Academia Scolds Bukele for Depicting Peace Accords as a 'Farce'". El Faro. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- Meléndez-Sánchez, Manuel (April 2023). "Analysis of Trends in Democratic Attitudes: El Salvador Report" (PDF). NORC at the University of Chicago. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- "Unhappy Anniversary: El Salvador Commemorates 25 Years of Peace". The Economist. San Salvador, El Salvador. 21 January 2017. OCLC 7065876503. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Ching, Erik K. (2014). Authoritarian El Salvador: Politics and the Origins of the Military Regimes, 1880–1940. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvpj7923. ISBN 9780268076993. JSTOR j.ctvpj7923. OCLC 875865660. Retrieved 20 October 2024.

- "Elections and Events 1980–1989". University of California, San Diego. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

External links

[edit]

Category:1970s in El Salvador

Category:1980s in El Salvador

Category:1990s in El Salvador

Category:20th century in El Salvador

Category:Civil wars involving the states and peoples of North America

Category:Civil wars of the 20th century

Category:Cold War

Category:Communism in El Salvador

Category:Coup-based civil wars

Category:Guerrilla wars

Category:MS-13

Category:Proxy wars

Category:Revolution-based civil wars

Category:Wars involving El Salvador

Totoposte War

[edit]| Totoposte Wars | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Signatories of the Treaty of Marblehead which ended the third war on 28 July 1906 | |||||

| |||||

| Belligerents | |||||

|

|

| ||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||

|

| |||||

| Strength | |||||

| Unknown | 55,000 | ||||

For adding new infoboxes to president pages

[edit]PizzaKing13/sandbox | |

|---|---|

| President of El Salvador | |

| Personal details | |

| Occupation | Politician |

Orders, decorations, and medals of El Salvador

[edit]The following article lists the civil and military orders, decorations, and medals presented by the Republic of El Salvador.

Civil decorations

[edit] Order of José Matías Delgado

Order of José Matías Delgado Order of José Simeón Cañas, Liberator of the Slaves

Order of José Simeón Cañas, Liberator of the Slaves 5 November 1811 Order of Merit

5 November 1811 Order of Merit Order of Military Merit

Order of Military Merit Order of Police Merit

Order of Police Merit 1839 Medal for Heroism

1839 Medal for Heroism 1839 Medal for Distinguished Valor

1839 Medal for Distinguished Valor Red Cross Medal of Merit

Red Cross Medal of Merit Meritorious Son or Daughter of El Salvador

Meritorious Son or Daughter of El Salvador

Military decorations

[edit] Golden Cross of the Armed Forces

Golden Cross of the Armed Forces Silver Medal of Valor

Silver Medal of Valor Gold Medal for Distinguished Service

Gold Medal for Distinguished Service Gold Medal of Merit

Gold Medal of Merit Medal for Excellence in Military Service

Medal for Excellence in Military Service Fighter's Medal

Fighter's Medal Wound Medal

Wound Medal Killed in Action Medal

Killed in Action Medal 1980–1992 Military Campaign Medal

1980–1992 Military Campaign Medal General Captain Gerardo Barrios Medal

General Captain Gerardo Barrios Medal Medal for the Graduate with Honors

Medal for the Graduate with Honors Command Medal of Military Education

Command Medal of Military Education Nu Tanesi Star

Nu Tanesi Star Star for Distinguished Services

Star for Distinguished Services Star for Merit

Star for Merit Star of Captain General Gerardo Barrios

Star of Captain General Gerardo Barrios Medal of Atonal, Warrior of Cuscatlán

Medal of Atonal, Warrior of Cuscatlán Medal Helmet of Valor

Medal Helmet of Valor Air Force Medal Protector Coeli

Air Force Medal Protector Coeli Mare Nostrum Medal

Mare Nostrum Medal Medal Torch of Doctor Manuel Enrique Araujo

Medal Torch of Doctor Manuel Enrique Araujo Medal Torch of Academic Excellence

Medal Torch of Academic Excellence

References

[edit]

Airports in El Salvador

[edit]United States Air Force Plant 42

[edit]

| United States Air Force Plant 42 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Air Force Materiel Command (AFMC) | |||||||||||

| Located near Palmdale, California in the United States | |||||||||||

USGS aerial image of United States Air Force Plant 42 | |||||||||||

| Coordinates | 34°37′43″N 118°05′04″W / 34.62861°N 118.08444°W[1] | ||||||||||

| Type | United States government manufacturing facility | ||||||||||

| Area | 5,832 acres (2,360 ha) | ||||||||||

| Site information | |||||||||||

| Owner | United States Air Force | ||||||||||

| Operator | United States Department of Defense | ||||||||||

| Condition | Operational | ||||||||||

| Site history | |||||||||||

| Built | 1935–1956 | ||||||||||

| Built by | Civil Aeronautics Administration / United States Air Force | ||||||||||

| In use | 1935–present | ||||||||||

| Garrison information | |||||||||||

| Current commander | Dr. David Smith | ||||||||||

| Garrison | 412th Test Wing Operating Location, Air Force Test Center | ||||||||||

| Occupants | Air Force Materiel Command | ||||||||||

| Airfield information | |||||||||||

| Identifiers | IATA: PMD, ICAO: KPMD, FAA LID: PMD, WMO: 72382 | ||||||||||

| Elevation | 2,542 feet (775 m) AMSL | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Sources: Federal Aviation Administration[2] | |||||||||||

United States Air Force Plant 42 (IATA: PMD, ICAO: KPMD, FAA LID: PMD),[3] formerly known as the Palmdale Airport and the Palmdale Army Airfield, is a United States Air Force aircraft manufacturing and maintenance facility located near Palmdale, California. Three aerospace manufacturers—Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman—have facilities and Plant 42, and other manufacturers formerly had facilities at the plant.

Plant 42 was established in 1953, although an airfield had existed on Plant 42's location since the 1930s. Various fighter aircraft, attack aircraft, trainer aircraft, bombers, and commercial airliners have been produced and tested at Plant 42. Some notable aircraft produced and tested at Plant 42 include the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress, the Lockheed L-1011 TriStar, the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird, the Northrop Grumman B-2 Spirit, and the Northrop Grumman B-21 Raider, which is currently being developed and tested at the plant. Plant 42 shares a runway with the Palmdale Regional Airport (PMD), although it has not serviced any scheduled commercial passenger flights since 2013.

Overview

[edit]Plant 42 is owned by the United States Air Force through the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base,[4] is operated by the United States Department of Defense, and is garrisoned by the 412th Test Wing Operating Location, Air Force Test Center.[5] It is located 3 miles (5 kilometers) northeast of Palmdale, California, covers 5,832 acres (2,360 hectares) of land, and is at an elevation of 2,542 feet (775 meters) above mean sea level.[6] Plant 42 is around 80 miles (129 kilometers) north of Los Angeles[7] and 23 miles (37 kilometers) southwest of Edwards Air Force Base. The land owned by Plant 42 is constrained to the north by Columbia Way (formerly named Avenue M), to the south by Avenue P, to the east by 40th Street East, and to the west by the Sierra Highway.[5]

Plant 42 employs around 9,000 people,[8] making it the second-largest employer in the Antelope Valley after Edwards Air Force Base.[7] Plant 42 has 3,200,000 square feet (297,290 square meters) of industrial space with various facilities which produce aircraft, maintenance and modify aircraft, and build spare parts for aircraft.[5]

In 1969, the United States House Committee on Appropriations stated that the mission of Plant 42 was to "augment the production potential of established aircraft industry by providing Government facilities to assigned contractors for final assembly, flight test and modification, and other approved Government contract work".[9]

Facilities

[edit]Airfield layout

[edit]Plant 42 has two runways and one military assault strip; the runways are designated as Runway 07/25 (12,002 feet (3,658 m) long and 200 feet (61 m) wide) and Runway 04/22 (12,001 feet (3,658 m) long and 150 feet (46 m) wide), and the assault strip is designated as Runway 072/252 (6,000 feet (1,829 m) long and 75 feet (23 m) wide). The two runways and the assault strip are all made of concrete.[6] Large aircraft primarily utilize Runway 07/25 while fighter and attack aircraft utilize Runway 04/22. The air force also utilizes both runways to practice touch-and-go landings.[10] The Los Angeles Air Route Traffic Control Center is located adjacent to Plant 42.[11] The Palmdale Flight Service Station was previously located at Plant 42.[9]

In January 2019, Plant 42 proposed replacing the airfield's 106-foot tall air traffic control tower which had been built in 1959, arguing that its view of the airfield's taxiways and parking spots was obstructed and that its replacement would be built in a more optimum location.[12] On July 5, 2019, a 7.1 magnitude earthquake damaged the air traffic control tower.[13] A new 160-foot tall air traffic control tower was completed at Plant 42 on November 30, 2022;[14] it was built by the United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and Stronghold Engineering,[15] and was constructed with an "advanced buckling-restrained brace frame" to minimize earthquake damage.[16]

In August 2020, the United States Department of Defense awarded J G Contracting a contract to perform construction and maintenance work at Plant 42 through July 2025.[17] In August 2021, the Department of Defense awarded KAL Architects Inc. a contract to perform "architect and engineering services" at Plant 42 through August 2026.[18]

Plant 42 consists of 10 sites.

Site 5 consists of the two runways.[12]

Manufacturing facilities

[edit]Three major manufacturers currently operate at Plant 42: Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman.[5] Additionally, Convair, Douglas, Hughes, IT&T, Lockheed Air Terminal, Lockheed California, McDonnell Douglas, Norair, and Rockwell International formerly had facilities at Plant 42.[5][7][9] Manufacturers at the plant either own their own facilities or lease facilities from the air force through the Government Owned Contractor Operated (GOCO) program. In total, there are eight production facilities.[5]

Some aircraft produced at Plant 42 are flown to Edwards Air Force Base, Area 51, or the Tonopah Test Range either on board a Lockheed C-5 Galaxy, a Boeing C-17 Globemaster III, or are flown under their own power.[19]

Boeing

[edit]- B-52 Stratofortress[citation needed]

- Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy[citation needed]

- Rockwell

Rockwell utilized Plant 42 for final assembly of the Space Shuttles,[20] as well as for producing parts and systems for the Space Shuttles. The company also serviced the B-1 Lancer at Plant 42.[7]

- North American

- A3J Vigilante[21]

- F-100 Super Sabre[21]

- T-39 Sabreliner[21]

- X-15[citation needed]

- XB-70 Valkyrie[citation needed]

- Convair

- Douglas

- Hughes

Lockheed Skunk Works

[edit]In 1956, the Lockheed Corporation signed a lease to utilize 237 acres (96 hectares) of land at Plant 42 for aircraft final assembly and aircraft testing.[7]

Final assembly for the SR-71 Blackbird occurred at Plant 42.[22]

- F-22 Raptor[citation needed]

- F-35 Lightning II[citation needed]

- L-1011 TriStar[citation needed]

- P-791[23]

- RQ-170 Sentinel[citation needed]

- X-33[24]

- X-55[25]

- Lockheed

- A-12[22]

- EC-130[26]

- F-104 Starfighter[21]

- F-117 Nighthawk[27]

- SR-71 Blackbird[28]

- T2V SeaStar[21]

- T-33 Shooting Star[21]

- U-2 Dragon Lady[27]

Northrop Grumman

[edit]Northrop Grumman developed the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber at Plant 42 during the 1980s.[29] The B-2 Spirit flew for the first time on July 17, 1989, and flew from Plant 42 to Edwards Air Force Base.[30] Plant 42 continues to service and maintenance the B-2 Spirit,[31][32] and every two to three years, the B-2's stealth coating is repaired at Plant 42.[33]

The Northrop Grumman B-21 Raider long-rang stealth bomber is being developed at Plant 42. The aircraft was publicly displayed for the first time on December 9, 2022,[34] and flew for the first time on November 10, 2023. The air force plans to purchase around 100 B-21's to replace its B-1 and B-2 fleet.[35]

- B-2 Spirit[29]

- B-21 Raider[29]

- MQ-4C Triton[29]

- RQ-4 Global Hawk[29]

- X-47B[citation needed]

- Northrop

NASA

[edit]NASA utilized Plant 42 to service the Space Shuttles until 2002 when it moved its servicing operations to Florida.[7]

Airline services

[edit]From the 1960s to 1980s, Los Angeles World Airports (LAWA) wanted to utilize the runways at Plant 42 as a part of an auxiliary airport to reduce congestion at the Los Angeles International Airport.[36] Additionally, LAWA purchased 17,000 acres (6,900 hectares) of land east of Plant 42 to construct a new airport known as Palmdale International Airport, however, no airport was ever built. Airlines did offer passenger services out of Plant 42; airlines utilized the plant's runways and a leased passenger terminal during the 1990s and 2000s, however, all commercial airlines have since ceased all routes to Plant 42.[7]

Janet, a United States Department of the Air Force-operated passenger airline, operates routes from Plant 42 to Harry Reid International Airport in Las Vegas, Nevada and to the Homey Airport, more commonly known as Area 51. Janet designates Plant 42 as "Station 1".[37]

Museums

[edit]Two museums are located adjacent to Plant 42: the Blackbird Airpark Museum and the Joe Davies Heritage Airpark. The Blackbird Airpark Museum displays 4 Cold War-era reconnaissance aircraft which were developed by the Lockheed Corporation,[38] while the Joe Davies Heritage Airpark displays 22 aircraft from multiple manufacturers which were designed, built, and flown at Plant 42.[39]

History

[edit]Pre-1953 use

[edit]

The Civil Aeronautics Administration designated the airfield, located in Palmdale, California, as "CAA Intermediate #5".[1]

From 1940 to 1946,[40] United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) leased the Palmdale Airport from Palmdale's irrigation district, during which, the Works Progress Administration built a 9,000-foot-long (2,743-meter) runway and a 5,000-foot-long (1,524-meter) auxiliary runway.[5] Renamed as the Palmdale Army Airfield, it was utilized as a sub-base to both the Muroc Army Airfield (the modern-day Edwards Air Force Base) and the Hammer Army Airfield (the modern-day Fresno Yosemite International Airport).[1] The USAAC utilized the Palmdale Army Airfield for North American B-25 Mitchell support training and for emergency landings.[7] In 1946, USAAC transfered ownership of the airfield to the Los Angeles County to resume operations as a municipal airport.[40]

Air force ownership

[edit]In 1951, the United States Air Force purchased 5,832 acres (2,360 hectares) of land from the Los Angeles County, and in 1953, officially established Plant 42[40] for the purpose of producing aircraft and testing jet aircraft.[7] The construction of Plant 42 led to Palmdale shifting from an agriculture-based economy to an aerospace manufacturing-based economy.[41]

In October 1993, the air force stated that it would review closing Plant 42 and the other seven air force plants nationwide as a result of a cut in defense spending after the end of the Cold War. Arnie Rodio, the mayor of Lancaster, California, opposed closing Plant 42, stressing its importance to the air force, while Howard Brooks, the executive director of the Antelope Valley Board of Trade, believed that Plant 42 would not be affected by the air force's review.[27] Contrarily, William J. Knight, a member of the California State Assembly and a retired air force colonel, supported closing the plant believing that it could be better utilized by private industry. He argued that if there would no longer be any military contracts at Plant 42, the plant would be useless and "essentially closed".[42]

In 1999, the United States Congress cut US$3.3 million from Plant 42's operating budget and various officials worried that such a budget cut would lead to Plant 42 being shutdown. Buck McKeon, a member of the United States House of Representatives from California's 25th congressional district, stated that the budget cut would be "disastrous".[43]

In January 2021, Plant 42 allowed the Samaritan's Purse humanitarian aid organization to utilize its runways to delivery emergency supplies to the Antelope Valley Hospital to treat patients of COVID-19.[44]

On March 26, 2021, John P. Roth, the United States Secretary of the Air Force, and Mike Garcia, a member of the United States House of Representatives from the then California's 25th congressional district, toured Plant 42. After the tour, Garcia stated that Plant 42 played a "critical role" in the United States' defense, "[helped] advance and improve" the United States military's "presence and strength in air and space", and that it was a "significant job source" for residents of his congressional district.[45]

During late-2020, the air force considered Plant 42 as a potential permanent headquarters for the United States Space Command. Brigadier General Matthew W. Higer, the commander of the 412th Test Wing, supported selecting Plant 42 as the space command's headquarters, stating, "Air Force Plant 42, already a vital part of our Nation's critical defense industrial base, is a natural fit for Headquarters U.S. Space Command".[46]

Commanders

[edit]Plant 42 was commanded by Joe Davies from 1963 to 1967.[28]

Major Peter Drinkwater commanded plant 42 during the early 1990s.[42]

Lieutenant Colonel Robert Catlin commanded Plant 42 during the late 1990s.[43]

Colonel Dwayne Robison commanded Plant 42 until July 1, 2020, when he relinquished command to Dr. David Smith.[47]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency

This article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency

- ^ a b c "California World War II Airfield Database". Airfields Database. Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ "FAA Airport Form 5010 for PMD" (PDF). United States Department of Transportation. 30 November 2023. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ "Palmdale Regional/USAF Plant 42 Airport". Business Air News. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ "Air Force Plant 42". Aerotech News. 30 December 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g "January 8, 1942: Palmdale Airport Becomes Plant 42". Air Force Test Center. Mojave, California. 8 January 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Palmdale USAF Plant 42 Airport". SkyVector. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Air Force Plant 42". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ "Palmdale USAF Plant 42 Airport". Los Angeles Air Route Traffic Control Center. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ a b c United States House Committee on Appropriations (1969). Department of Defense Appropriations for 1970: Hearings ... Ninety-First Congress, First Session. pt. 1–2. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Publishing Office. pp. 816–817. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ "Palmdale International Airport, New Airport: Environmental Impact Statement, Volume 1". Los Angeles, California: Federal Aviation Administration. February 1979. p. 51. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ "Los Angeles Air Route Traffic Control Center, California". Center for Land Use Interpretation. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Air Traffic Control Tower Replacement Air Force Plant 42, Palmdale, California". City of Palmdale. Palmdale, California. January 2019. pp. 1-1 & 1-3 & 2-2. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ Everstine, Brian W. (8 July 2019). "Earthquakes Damage Edwards AFB Plant 42, Navy's China Lake Base". Air and Space Forces Magazine. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ Grooms, Larry (1 December 2022). "New AF Plant 42 Control Tower Dedicated". Aero Tech News. Palmdale, California. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ O'Dell, Dena (8 December 2022). "Corps Joins Air Force to Unveil Completion of Air Traffic Control Tower at Plant 42, Described as "Center of the Aerospace Testing Universe"". United States Army Corps of Engineers. Palmdale, California. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "Construct Air Traffic Control Tower, Air Force Plant 42". Stronghold Engineering. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "Contracts For Aug. 7, 2020". United States Department of Defense. 7 August 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ "Contracts For Aug. 31, 2021". United States Department of Defense. 31 August 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ "Air Force Plant 42". Dreamland Resort. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "Overland Transport of Space Shuttle Orbiter, USAF Plant 42 to Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards Air Force Base (AFB): Environmental Impact Statement". NASA. January 1976. p. i. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "FAA Team Study of R-484 & Southern California ATC Problems". Washington, D.C.: Federal Aviation Administration. 18 February 1959. p. 213. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ a b Goodall, James C. (13 May 2021). 75 years of the Lockheed Martin Skunk Works. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 147 & 171. ISBN 9781472846457. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ Lobner, Peter (16 June 2023). "Lockheed Martin – P-791 Hybrid Airship" (PDF). Lynceans. p. 7. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ X-33 Advanced Technology Demonstrator Vehicle Program [CA,UT,WA]: Environmental Impact Statement. NASA. June 1997. p. 3-12. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ Kaufman, Derek (3 June 2009). "Advanced Composite Cargo Aircraft Makes First Flight". United States Air Force. Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. Archived from the original on 10 June 2009. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ van Geffen, Theo (2022). "Joint Task Force Proven Force and the Gulf War (Part 2)". Air & Space Power History. 69 (2). Air Force Historical Foundation: 12–13. JSTOR 48712438.

- ^ a b c Chandler, John (14 October 1993). "Air Force's Plant 42 May Face Closure: Military: The Only California Facility is Among Eight Nationwide to be Studied". Los Angeles Times. Palmdale, California. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ a b c Gatlin, Allison (20 August 2021). "Palmdale Legend Davies is Honored". Antelope Valley Press. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Air Force B-21 Raider Long-Range Strike Bomber". Congressional Research Service. 22 September 2021. p. 8. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ "Strategic Bombers: B-2 Program Status and Current Issues : Report to the Chairman, Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives". Washington, D.C.: Government Accountability Office. February 1990. p. 9. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ Casem, Giancarlo (29 September 2020). "Plant 42 Gears Up "Spirit of Pennsylvania" for Next Mission". Edwards Air Force Base. Edwards Air Force Base. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ Trevithick, Joseph (22 September 2022). "Damaged B-2 Returns To Palmdale For Repairs A Year After Landing Mishap". The Drive. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ Stephens, Hampton (11 July 2003). "Contractor Seeks $31 Million in DOD Spending Bill: Feinstein Pushes for Funds to Fix Cracks in B-2's Stealthy Skin". Inside the Air Force. 14 (28). Inside Washington Publishers: 9. JSTOR 24792164.

- ^ Stone, Mike; Whitcomb, Dan (3 December 2022). Gregorio, David; Feast, Lincoln (eds.). "Northrop Grumman Unveils B-21 Nuclear Bomber for U.S. Air Force". Reuters. Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ Swanson, David; Stone, David; Insinna, Valerie (11 November 2023). Paul, Franklin (ed.). "US Air Force's New B-21 Raider "Flying Wing" Bomber Takes First Flight". Reuters. Palmdale and Washington, D.C. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ McGarry, T. W. (8 May 1988). "Plans for "Superport" Announced in 1968: Palmdale Airport: Undying Dream". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ "Janet Flight Schedule". Dreamland Resort. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ K., Igor (7 March 2019). "Air Force Flight Test Museum – Blackbird Airpark". Air Museum Guide. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ K., Igor (27 April 2017). "Joe Davies Heritage Airpark at Palmdale Plant 42". Air Museum Guide. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ a b c "Joe Davies Heritage Airpark Brochure". City of Palmdale. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ "Antelope Valley Frequently Asked Questions". County of Los Angeles Public Library. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ a b Sneiderman, Phil; Moeser, Sharon (18 October 1993). "Closing Plant 42 Could Be Beneficial, Knight Says: Economy: The Assemblyman Says Area Could See Job Gains if the Facility is Used by Private Industry. Many Disagree". Los Angeles Times. Palmdale, California. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ a b "The State of United States Military Forces: Hearing Before the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives, One Hundred Sixth Congress, First Session: Hearing Held January 20, 1999, Volume 4". Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. 1999. pp. 141 & 169. ISBN 9780160600203. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ Casem, Giancarlo (15 January 2021). "Aircraft Carrying Supplies for Emergency Field Hospital Lands at Plant 42". United States Department of Defense. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "Secretary of US Air Force Tours Plant 42". Antelope Valley Press. Palmdale, California. 30 March 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "Palmdale In The Running For Future, Permanent Home Of US Space Command". CBS News. Palmdale, California. 24 August 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ Casem, Giancarlo (1 July 2020). "Plant 42 Changes Leadership". Air Force Test Center. Edwards Air Force Base. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Gatlin, Allison (2 December 2022). "Another Success Story from Plant 42". Antelope Valley Press. Palmdale, California. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

External links

[edit]

Category:1935 establishments in California

Category:1953 establishments in California

Category:Airfields of the United States Army Air Forces in California

Category:Antelope Valley

Category:Boeing manufacturing facilities

Category:Buildings and structures in Palmdale, California

Category:Edwards Air Force Base

Category:Government buildings completed in 1953

Category:Industrial buildings completed in 1935

Category:Lockheed Martin-associated military facilities

Category:Military facilities in Greater Los Angeles

Category:Military facilities in the Mojave Desert

Category:Plants of the United States Air Force

Category:Science and technology in Greater Los Angeles

Municipalities template

[edit][MUNICIPALITY NAME] | |

|---|---|

| Country | |

| Established | 1 May 2024 |

| Government | Mayor–council |

[MUNICIPALITY NAME] (Spanish for "[MUNICIPALITY NAME TRANSLATED]") is a municipality of El Salvador. [MUNICIPALITY NAME] was established on 1 May 2024. The municipality consists of [NUMBER] districts: [DISTRICT NAMES], all of which were municipalities before [MUNICIPALITY NAME]'s establishment.

History

[edit]On 1 June 2023, Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele presented a bill, known as the Special Law to Restructure Municipal Territory, to the Legislative Assembly of El Salvador proposing the reduction number of the country's 262 municipalities down to 44. The Legislative Assembly approved the bill on 13 June. The borders of [MUNICIPALITY NAME] and the number of districts, third-level subdivisions, it would have were outlined in the bill.[1]

During the 2024 municipal elections, [NAME] of (the) [PARTY] (political party) was elected as [MUNICIPALITY NAME]'s first mayor. [IF APPLICABLE: Prior to being elected as mayor of [MUNICIPALITY NAME], [LAST NAME] served as the mayor of [DISTRICT NAME] since [YEAR].<ref here>

Districts

[edit][MUNICIPALITY NAME] is composed of [NUMBER] districts, third-layer subdivisions which formerly were municipalities.[2]

Government

[edit][MUNICIPALITY NAME] is governed by a mayor and a municipal council, consisting of 1 trustee, 4 proprietary aldermen, and 4 substitute aldermen. Mayors and municipal councils are elected every three years.[3] The following table lists all the mayors of the municipality since its establishment in May 2024.

SANTA ANA CENTRO and SAN MIGUEL CENTRO: [MUNICIPALITY NAME] is governed by a mayor and a municipal council, consisting of 1 trustee, 10 proprietary aldermen, and 4 substitute aldermen. Mayors and municipal councils are elected every three years.[4] The following table lists all the mayors of the municipality since its establishment in May 2024.

SAN SALVADOR CENTRO and SAN SALVADOR ESTE: [MUNICIPALITY NAME] is governed by a mayor and a municipal council, consisting of 1 trustee, 10 proprietary aldermen, and 4 substitute aldermen. Mayors and municipal councils are elected every three years.[5] The following table lists all the mayors of the municipality since its establishment in May 2024.

| Mayor | Elected | Term of office | Political party | Ref. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assumed office | Left office | Duration | |||||

| 2024 | 1 May 2024 | Incumbent | 194 days | ||||

References

[edit]- ^ García, Jessica (13 June 2023). "Asamblea Aprueba Reducir de 262 a 44 el Número de Municipios en El Salvador" [The Assembly Approves to Reduce the Number of Municipalities in El Salvador from 262 to 44]. El Diario de Hoy (in Spanish). Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ "Los 44 Municipios de El Salvador a Partir del 1 de Mayo de 2024" [The 44 Municipalities of El Salvador Beginning on 1 May 2024]. El Mundo (in Spanish). 26 February 2024. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ "Los 622 Funcionarios Públicos que Elegirán los Salvadoreños en 2024" [The 622 Public Workers that Salvadorans Will Elect in 2024]. El Mundo (in Spanish). 3 July 2023. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ "Los 622 Funcionarios Públicos que Elegirán los Salvadoreños en 2024" [The 622 Public Workers that Salvadorans Will Elect in 2024]. El Mundo (in Spanish). 3 July 2023. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ "Los 622 Funcionarios Públicos que Elegirán los Salvadoreños en 2024" [The 622 Public Workers that Salvadorans Will Elect in 2024]. El Mundo (in Spanish). 3 July 2023. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

Municipalities to do

[edit]- Ahuachapán Centro

- Ahuachapán Norte

- Ahuachapán Sur

- Cabañas Este

- Cabañas Oeste

- Chalatenango Centro

- Chalatenango Norte

- Chalatenango Sur

- Cuscatlán Norte

- Cuscatlán Sur

- La Libertad Centro

- La Libertad Costa

- La Libertad Este

- La Libertad Norte

- La Libertad Oeste

- La Libertad Sur

- La Paz Centro

- La Paz Este

- La Paz Oeste

- La Unión Norte

- La Unión Sur

- Morazán Norte

- Morazán Sur

- San Miguel Centro

- San Miguel Norte

- San Miguel Oeste

- San Salvador Centro

- San Salvador Este

- San Salvador Norte

- San Salvador Oeste

- San Salvador Sur

- San Vicente Norte

- San Vicente Sur

- Santa Ana Centro

- Santa Ana Este

- Santa Ana Norte

- Santa Ana Oeste

- Sonsonate Centro

- Sonsonate Este

- Sonsonate Norte

- Sonsonate Oeste

- Usulután Este

- Usulután Norte

- Usulután Oeste

Ahuachapán Centro

[edit]Ahuachapán Centro | |

|---|---|

| Country | |

| Department | |

| Established | 1 May 2024 |

| Government | Mayor–council |

| Area | |

• Total | 449 km2 (173 sq mi) (19th) |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | 162,590 (8th) |

• Density | 325.8/km2 (843.8/sq mi) (19th) |

Ahuachapán Centro (Spanish for "Central Ahuachapán") is a municipality of El Salvador. Ahuachapán Centro was established on 1 May 2024. The municipality consists of four districts: Ahuachapán, Apaneca, Concepción de Ataco, and Tacuba, all of which were municipalities before Ahuachapán Centro's establishment.

History

[edit]On 1 June 2023, Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele presented a bill to the Legislative Assembly of El Salvador proposing the reduction number of the country's 262 municipalities down to 44. The Legislative Assembly approved the bill on 7 June.[1]

Districts

[edit]Ahuachapán Centro is composed of four districts, third-layer subdivisions which formerly were municipalities. Those districts are Ahuachapán, Apaneca, Concepción de Ataco, and Tacuba.[2]

Government

[edit]Ahuachapán Centro is governed by a mayor and a municipal council, consisting of 1 trustee, 4 proprietary aldermen, and 4 substitute aldermen. Mayors and municipal councils are elected every three years.[3] The following table lists all the mayors of the municipality since its establishment in May 2024.

| Mayor | Elected | Term of office | Political party | Ref. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assumed office | Left office | Duration | |||||

| 2024 | 1 May 2024 | Incumbent | 194 days | ||||

References

[edit]- ^ García, Jessica (13 June 2023). "Asamblea Aprueba Reducir de 262 a 44 el Número de Municipios en El Salvador" [The Assembly Approves to Reduce the Number of Municipalities in El Salvador from 262 to 44]. El Diario de Hoy (in Spanish). Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ "Los 44 Municipios de El Salvador a Partir del 1 de Mayo de 2024" [The 44 Municipalities of El Salvador Beginning on 1 May 2024]. El Mundo (in Spanish). 26 February 2024. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ "Los 622 Funcionarios Públicos que Elegirán los Salvadoreños en 2024" [The 622 Public Workers that Salvadorans Will Elect in 2024]. El Mundo (in Spanish). 3 July 2023. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

Category:Municipalities of the Ahuachapán Department

Ahuachapán Norte

[edit]Ahuachapán Norte | |

|---|---|

| Country | |

| Department | |

| Established | 1 May 2024 |

| Government | Mayor–council |

Ahuachapán Norte (Spanish for "North Ahuachapán") is a municipality of El Salvador. Ahuachapán Norte was established on 1 May 2024. The municipality consists of four districts: Atiquizaya, El Refugio, San Lorenzo, and Turín, all of which were municipalities before Ahuachapán Norte's establishment.

References

[edit]Category:Municipalities of the Ahuachapán Department

Ahuachapán Sur

[edit]Ahuachapán Sur | |

|---|---|

| Country | |

| Department | |

| Established | 1 May 2024 |

| Government | Mayor–council |

Ahuachapán Sur (Spanish for "South Ahuachapán") is a municipality of El Salvador. Ahuachapán Sur was established on 1 May 2024. The municipality consists of four districts: Guaymango, Jujutla, San Francisco Menéndez, and San Pedro Puxtla, all of which were municipalities before Ahuachapán Sur's establishment.

References

[edit]Category:Municipalities of the Ahuachapán Department

Christian Guevara

[edit]

Christian Guevara | |

|---|---|

| Deputy of the Legislative Assembly of El Salvador from San Salvador | |

| Assumed office 1 May 2021 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Christian Reynaldo Guevara Guadrón El Salvador |

| Political party | Nuevas Ideas |

| Alma mater | Central American University Ibero-American University |

| Occupation | Politician, businessman, journalist |

Christian Reynaldo Guevara Guadrón is a Salvadoran politician, businessman, and journalist who serves as a leader of the Nuevas Ideas political party in the Legislative Assembly of El Salvador.

Early life

[edit]Guevara attended the Central American University in San Salvador and the Ibero-American University in Mexico City, Mexico, where he earned a degree in communications and journalism.[1]

In 2008, Guevara jointly established the E-Com distribution company with Porfirio de Jesús Chica Argueta, a supplement deputy of the Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA).[2]

Political career

[edit]Guevara's supplement deputy is Jenny del Carmen Solano Chávez.[3]

Guevara served as the chairman of the Legislative Assembly's treasury and special budget commission;[4] and as the secretary of the ad doc commission to study the Water Resources Law draft.[5] He was also a member of the politics commission.[6]

In June 2021, the United States Department of State listed Guevara on the Section 353 List of Corrupt and Undemocratic Actors and placed sanctions on him for proposing the Gang Prohibition Law which allegedly censored freedom of expression.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ "Perfil Público del Diputado: Christian Reynaldo Guevara Guadrón" [Public Profile of the Deputy: Christian Reynaldo Guevara Guadrón]. Legislative Assembly of El Salvador (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ Lemus, Efren; Labrador, Gabriel; Rauda, Nelson (19 February 2021). "El Candidato de NI que Promete Combatir a los Evasores Está Insolvente con Hacienda" [The NI Candidate Who Promises to Fight Evaders Is Insolvent with the Treasury]. El Faro (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ "Diputado Christian Reynaldo Guevara Guadrón y Suplente" [Deputy Christian Reynaldo Guevara Guadrón and Supplement]. Legislative Assembly of El Salvador (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ "Comisión: Hacienda y Especial del Presupuesto" [Commission: Treasury and Special Budget]. Legislative Assembly of El Salvador (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 1 December 2023. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ "Comisión: Ad Hoc para que Estudie el Proyecto de Ley de Recursos Hídricos" [Commission: Ad Hoc to Study the Water Resources Law Draft]. Legislative Assembly of El Salvador (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ "Comisión: Política" [Commission: Politics]. Legislative Assembly of El Salvador (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 29 September 2023. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ Méndez Dardón, Ana María (21 July 2022). "Engel List: What is the United States Telling Central America?". Washington Office on Latin America. Archived from the original on 5 April 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

Category:21st-century Salvadoran politicians

Category:Living people

Category:Members of the Legislative Assembly of El Salvador

Category:Nuevas Ideas politicians