Tardigrades on the Moon

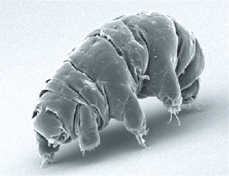

On April 11, 2019, the Israeli spacecraft Beresheet crashed into the Moon during a failed landing attempt.[1] Its payload included a few thousand tardigrades (also known as water bears). Initial reports suggested they could have survived the crash landing.[2][3][4] If any of them did survive, they would be the tenth species to reach the surface of the Moon, after humans, brought by the American Apollo program, and fruit flies, silkworms, cottonseed, potato, rapeseed, Arabidopsis thaliana (a flowering plant), as well as yeast — the latter seven all taken to the moon by China's Chang'e 4.[5]

We believe the chances of survival for the tardigrades... are extremely high.

— Nova Spivack, author and businessman, [2]

Lunar crash

[edit]The lander crash-landed on the surface of the Moon on April 11, 2019, due to technical problems involving the loss of a gyroscope during the last phase of the lunar landing.[6] The lander later hit the surface at more than 3,000 km/h.[7]

Tardigrade hardiness

[edit]Tardigrades can withstand extremely low temperatures close to absolute zero[8] and high temperatures over 400 K.[9] In comparison, temperatures on the Moon range from 140 K at night to 400 K during the day.[10] They are also able to survive large doses of ionizing radiation and the vacuum of outer space.[9][11][3]

Tardigrades are a valuable model organism for researching the possibility of life in space because of their exceptional ability to survive harsh environments, such as high radiation, desiccation, and extremely high temperatures.[12]

Due to their intricate anatomy, ability to adapt to limited lab settings, and unique ability to stop metabolism in order to survive extreme circumstances like anhydrobiosis and cryobiosis, water bears, also known as tardigrades, are ideal model organisms for space biology. Their adaptability has been tested in Low Earth Orbit, according to Guidetti et al. (2012), and the results are crucial for preserving space and lunar habitats for life.[13]

Tardigrades can undergo all five types of cryptobiosis, reducing their metabolism to less than 0.01% and their water content to 1% compared to their normal state.[9][14] They can be revived from this state even decades later.[15]

2021 tardigrade bullet research

[edit]In 2021, researchers at the Queen Mary University of London placed tardigrades in hollow nylon bullets and fired them from a two stage light gas gun into sand targets. The tested tardigrades were able to survive impacts of up to 3,000 km/h and momentary shock pressures of up to 1.14 GPa. The results suggest the tardigrades were unlikely to survive the crash because the shock pressure of the lander's metal frame hitting the surface would have been well above 1.14 GPa.[16][14]

Possible contamination

[edit]The possibility of surviving tardigrades raised concerns about possible contamination of the Moon with biological material.[7] If recovered and hydrated they could be awakened, but this is unlikely to happen because of the lack of liquid water on the Moon.[15]

Spilling tardigrades across the Moon is legal.[17][18] The Outer Space Treaty only explicitly bans weapons and experiments or tools that could interfere with other missions.[1] Large space agencies typically follow guidelines for sterilizing mission equipment, but there is no single entity to enforce these rules globally.[15]

See also

[edit]- Animals in space

- List of microorganisms tested in outer space

- List of species that have landed on the Moon

References

[edit]- ^ a b Mindy Weisberger (2019-08-06). "Thousands of Tardigrades Stranded on the Moon After Lunar Lander Crash". livescience.com. Retrieved 2023-06-14.

- ^ a b "Tardigrades: 'Water bears' stuck on the moon after crash". BBC News. 2019-08-07. Retrieved 2023-06-14.

- ^ a b Resnick, Brian (2019-08-06). "Tardigrades, the toughest animals on Earth, have crash-landed on the moon". Vox. Retrieved 2023-06-14.

- ^ "Did these tardigrades survive crash-landing on the moon?". earthsky.org. 2019-08-14. Retrieved 2023-06-14.

- ^ "Change-4 Probe lands on the moon with "mysterious passenger" of CQU". Archived from the original on 18 January 2019. Retrieved 2024-04-28.

- ^ Palkapublished, Laurent (2024-03-02). "Could tardigrades have colonized the moon?". Space.com. Retrieved 2024-03-02.

- ^ a b "What Happened to Beresheet?". Davidson Institute of Science Education. 2020-02-20. Retrieved 2023-06-14.

- ^ "Tardigrade | Facts & Lifespan | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2023-04-28. Retrieved 2023-06-14.

- ^ a b c "Tardigrades". Tardigrade. Retrieved 2023-06-14.

- ^ Urrutia, Doris Elin; updated, Tim Sharp last (2022-02-28). "What is the Temperature on the Moon?". Space.com. Retrieved 2023-06-14.

- ^ "Space creatures". BBC Nature. 2011-05-17. Retrieved 2023-06-14.

- ^ Erdmann, W.; Kaczmarek, Ł. (2016). "Tardigrades in space research - past and future". Origins of Life and Evolution of Biospheres. 47 (4): 545–553. doi:10.1007/s11084-016-9522-1. PMC 5705745. PMID 27766455.

- ^ Guidetti, R.; Rizzo, A. M.; Altiero, T.; Rebecchi, L. (2012). "What can we learn from the toughest animals of the Earth? Water bears (tardigrades) as multicellular model organisms in order to perform scientific preparations for lunar exploration". Planetary and Space Science. 74 (1): 97–102. Bibcode:2012P&SS...74...97G. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2012.05.021.

- ^ a b "Hardy water bears survive bullet impacts—up to a point". www.science.org. Retrieved 2023-06-14.

- ^ a b c Mindy Weisberger (2019-08-15). "There Are Thousands of Tardigrades on the Moon. Now What?". livescience.com. Retrieved 2023-06-14.

- ^ Traspas, Alejandra; Burchell, Mark J. (2021-07-01). "Tardigrade Survival Limits in High-Speed Impacts—Implications for Panspermia and Collection of Samples from Plumes Emitted by Ice Worlds". Astrobiology. 21 (7): 845–852. doi:10.1089/ast.2020.2405. ISSN 1531-1074. PMC 8262385. PMID 33978458.

- ^ Oberhaus, Daniel. "A Crashed Israeli Spacecraft Spilled Tardigrades on the Moon". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2023-06-14.

- ^ Yasemin Saplakoglu (2019-08-13). "Tardigrades and Poop: What Does Space Law Say About Moon Clutter?". livescience.com. Retrieved 2023-06-14.