CAESAR (spacecraft)

An artist's concept of CAESAR obtaining a sample from comet 67P. | |

| Mission type | Sample return |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| Website | caesar |

| Mission duration | 14 years, 3 months (proposed) |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | Northrop Grumman (proposed)[1] |

| Dimensions | Solar panels length: 43.5 m [2] |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | August 2024 (proposed)[3] |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | November 2038 (proposed)[3][4] |

| Landing site | Utah Test and Training Range[3] |

| Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko orbiter | |

| Orbital insertion | January 2029 (proposed)[3] |

| Orbital departure | February 2032 (proposed)[3] |

| Sample mass | 80 to 800 g (2.8 to 28.2 oz) |

CAESAR (Comet Astrobiology Exploration Sample Return) is a sample-return mission concept to comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko. The mission was proposed in 2017 to NASA's New Frontiers program mission 4, and on 20 December 2017 it was one of two finalists selected for further concept development. On 27 June 2019, the other finalist, the Dragonfly mission, was chosen instead.[5]

Had it been selected in June 2019, it would have launched between 2024 and 2025, with a capsule delivering a sample back to Earth in 2038. The Principal Investigator is Alexander Hayes of Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. CAESAR would be managed by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. Curation of the returned sample would take place at NASA's Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science Directorate, based at Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas.

The CAESAR team chose comet 67P over other cometary targets in part because the data collected by the Rosetta mission, which studied the comet from 2014 to 2016, allows the spacecraft to be designed to the conditions there, increasing the mission's chance of success.[6] The Rosetta mission also provides a vast geologic context for this mission's sample-return analysis.

Overview

[edit]

The two New Frontiers program Mission 4 finalists, announced on 20 December 2017, were Dragonfly to Titan, and CAESAR.[7] Comet 67P was previously explored by the European Space Agency's Rosetta probe and its lander Philae during 2014-2016 to determine its origin and history. Squyres explained that knowing the existing conditions at the comet allows them to design systems that would dramatically improve the chances for success.[6]

The CAESAR and Dragonfly missions received US$4 million funding each through the end of 2018 to further develop and mature their concepts.[6] NASA selected the Dragonfly mission on 27 June 2019 to build and launch in 2026.[5][7][6]

Background

[edit]A comet sample-return mission was one of the goals in a list of options for a New Frontiers mission in both the 2003 and the 2011 Planetary Science Decadal Survey, which were guiding surveys among those in the scientific community of what and where NASA should prioritize.[8] Another comet mission proposal, Comet Hopper, was one of three Discovery Program finalists that received US$3 million in May 2011 to develop a detailed concept study; however, it was not selected.[9] NASA has launched several missions to comets in the late 1990s and 2000s; these missions include Deep Space 1 (launched 1998), Stardust (launched 1999), CONTOUR (launched 2002 but failed after launch), and Deep Impact (launched 2005), as well as some participation on the Rosetta mission.

Astrobiology

[edit]CAESAR's objectives were to understand the formation of the Solar System and how these components came together to form planets and give rise to life.[4] Some researchers have hypothesized that Earth may have been seeded with organic compounds early in its development by tholin-rich comets, providing the raw material necessary for life to emerge.[2][10][11] Tholins were detected by the Rosetta mission to comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko.[12][13]

Spacecraft

[edit]The spacecraft would be built by Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems and it would inherit technology used by the successful Dawn mission.[1] Navigation, sample site selection, and sample documentation are enabled by the camera suite, provided by Malin Space Science Systems.[4] This camera suite consists of six cameras of varying fields of view and focal ranges: narrow angle camera (NAC), medium angle camera (MAC), touch-and-go camera (TAGCAM), two navigation cameras (NAVCAMs), and a sample container camera (CANCAM).[14]

The robotic arm (TAG) and the Sample Acquisition System would be provided by Honeybee Robotics.[4] The sample return capsule and heatshield are provided by the Japanese space agency JAXA.[2]

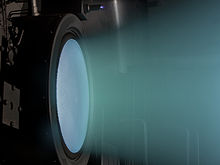

Propulsion

[edit]

The propulsion system on CAESAR would be NASA's Evolutionary Xenon Thruster (NEXT),[3][4] a type of solar electric propulsion. It would employ three NEXT thrusters, with one used as a spare.[15] The propellant is xenon.

Sample return

[edit]The spacecraft would not land on the comet, but would momentarily contact the surface with its TAG (Touch-And-Go) robotic arm, as done by OSIRIS-REx on an asteroid, including raising the solar arrays into a Y-shaped configuration to minimize the chance of dust accumulation during contact and provide more ground clearance.[3] The sampler mechanism on the arm would produce a burst of nitrogen gas to blow regolith particles into the sampler head located at the end of the arm. CAESAR would collect between 80 and 800 g (2.8 and 28.2 oz) of regolith from the comet. The maximum pebble size would be 4.5 cm (1.8 in).[3] The system has enough compressed nitrogen gas for three samplings.[2]

The system would separate the volatiles from the solid substances into separate containers and preserve the samples cold for the return trip.[2][16] The spacecraft would head back to Earth and drop off the sample in a capsule, which would re-enter Earth's atmosphere and parachute down to the surface in 2038.[6] The sample-return capsule (SRC) would be provided by JAXA and its design is based upon the SRC flown on the Hayabusa and Hayabusa2 spacecraft.[4] The capsule would parachute down at the Utah Test and Training Range (UTTR), and it would be transported to NASA's Johnson Space Center for curation and analyses at the laboratory called Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science Directorate (ARES).[1] A small portion of the sample will also be curated at Japan's Extraterrestrial Sample Curation Center.[2] Most of the sample (≥75% of the total) would be preserved for analysis by future generations of scientists.[16][2]

See also

[edit]- List of missions to comets

- TAGSAM – Regolith scoop used on asteroid Bennu by the NASA probe OSIRIS-REx

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Glavin, Daniel; Squyres, Steven (2018). An Overview of the Comet Astrobiology Exploration Sample Return (CAESAR) New Frontiers Mission. 20th EGU General Assembly. 4–13 April 2018. Vienna, Austria. Bibcode:2018EGUGA..20.4823G.

- ^ a b c d e f g Squyres, Steven (7 November 2018). "PSW 2399 Comets and the Origin of Life". PSW Science. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Squyres, Steve (2018). CAESAR: Project Overview (PDF). 18th Meeting of the NASA Small Bodies Assessment Group. 17–18 January 2018. Ames Research Center, California. Lunar and Planetary Institute.

- ^ a b c d e f Messenger, Scott R. (2018). The CAESAR New Frontiers Comet Sample Return Mission. Japan Geosciences Union Meeting. 20–24 May 2018. Chiba, Japan. hdl:2060/20180002990. JSC-E-DAA-TN54564.

- ^ a b Brown, David (27 June 2019). "NASA Announces New Dragonfly Drone Mission to Explore Titan". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Chang, Kenneth (19 December 2017). "Finalists in NASA's Spacecraft Sweepstakes: A Drone on Titan, and a Comet-Chaser". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ a b Glowatz, Elana (20 December 2017). "NASA's New Frontier Mission Will Search For Alien Life Or Reveal The Solar System's History". International Business Times.

- ^ "New Frontiers Program: Overview". NASA. Archived from the original on 26 January 2017.

- ^ Taylor, Kate (9 May 2011). "NASA picks project shortlist for next Discovery mission". Tech Guru Daily. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ^ Sagan, Carl & Khare, Bishun (11 January 1979). "Tholins: organic chemistry of interstellar grains and gas". Nature. 277 (5692): 102–107. Bibcode:1979Natur.277..102S. doi:10.1038/277102a0. S2CID 4261076.

- ^ McDonald, Gene D.; et al. (July 1996). "Production and Chemical Analysis of Cometary Ice Tholins". Icarus. 122 (1): 107–117. Bibcode:1996Icar..122..107M. doi:10.1006/icar.1996.0112.

- ^ Pommerol, A.; et al. (November 2015). "OSIRIS observations of meter-sized exposures of H2O ice at the surface of 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko and interpretation using laboratory experiments" (PDF). Astronomy & Astrophysics. 583. A25. Bibcode:2015A&A...583A..25P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201525977.

- ^ Wright, I. P.; et al. (31 July 2015). "CHO-bearing organic compounds at the surface of 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko revealed by Ptolemy". Science. 349 (6247): aab0673. Bibcode:2015Sci...349b0673W. doi:10.1126/science.aab0673. PMID 26228155. S2CID 206637053.

- ^ Soderblom, Jason; et al. (2018). The CAESAR New Frontiers Mission: Overview and Imaging Objectives. 2018 CALCON Technical Meeting. 18–21 June 2018. Logan, Utah.

- ^ Schmidt, George; et al. (2018). Electric Propulsion Research and Development at NASA. Spacecraft Propulsion 2018. 14–18 May 2018. Seville, Spain. hdl:2060/20180004691. SP-2018-00389.

- ^ a b Nakamura-Messenger, K.; et al. (2018). The CAESAR New Frontiers Mission: 5. Contamination, Recovery, and Curation (PDF). 49th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. 19–23 March 2018. The Woodlands, Texas.