Ocean Worlds Exploration Program

The Ocean Worlds Exploration Program (OWEP) is a NASA program[1] to explore ocean worlds in the outer Solar System that could possess subsurface oceans to assess their habitability and to seek biosignatures of simple extraterrestrial life.

Prime targets include moons that harbor hidden oceans beneath a shell of ice: Europa, Enceladus, and Titan. A host of other bodies in the outer Solar System are inferred by a single type of observation or by theoretical modeling to have subsurface oceans.

The US House Appropriations Committee approved the bill on May 20, 2015, and directed NASA to create the Ocean Worlds Exploration Program.[2] The "Roadmaps to Ocean Worlds" (ROW) was started in 2016,[3][4] and was presented in January 2019.[5] The formal program is being implemented within the agency by supporting the Europa Clipper orbiter mission to Europa,[3][6] and the Dragonfly mission to Titan. The program is also supporting concept studies for a proposed Europa Lander,[7] and concepts to explore the moon Triton.[8][5] Amanda Hendrix and Terry A. Hurford are the co-leads of the NASA Roadmaps to Oceans World Group.[5][9]

History

[edit]

The chief author of NASA's budget proposal is John Culberson, who was at the time the head of the science subcommittee in the House of Representatives. In Spring 2015 he presented a budget request, creating the possibility of an all-new NASA mission program.[11][12] The House Appropriations Committee approved its version of the FY2016 House Appropriations Commerce-Justice-Science (CJS) bill on May 20, 2015.[6] Therefore, the Committee directed NASA to create the Ocean Worlds Exploration Program whose primary goal is to discover extant life on another world using a mix of Discovery, New Frontiers and Flagship class missions consistent with the recommendations of current and future Planetary Science Decadal Surveys.[3]

In the FY2017 Budget Request, the committee recommended $348 million for "Outer Planets" and "Ocean Worlds," of which not less than $260 million is for the Europa Clipper orbiter and lander, with launch of the orbiter in 2025[13] and the potential Europa Lander shortly after.[14]

A 2017 technical analysis stated that the technical challenges are enormous, and that "Without a genuinely strategic program plan, the great promise of an OWEP [Ocean Worlds Exploration Program] is highly likely to remain unfulfilled."[15] The report noted that development of OWEP-enabling technologies must currently compete for priority with other Solar System objectives, which is not useful for strategic planning. The report recommends common, multi-mission technical infrastructure and secure funding to develop it.[15]

The Roadmaps to Ocean Worlds (ROW) report was submitted and it was published in January 2019.[5]

Science goals

[edit]

On Earth, itself an ocean world, liquid water is essential to life as we know it. A question is whether the dark, alien oceans of the outer Solar System could be habitable for simple life forms, and if so, what their biochemistry might be.[16]

The goals of the Ocean Worlds Exploration Program are to "identify ocean worlds, characterize their oceans, evaluate their habitability, search for life, and ultimately understand any life we find."[5]

Exploring these moons could help to answer the question of how life arose on Earth and whether it exists anywhere else in the Solar System.[17] It may also be possible to find pre-biotic chemistry occurring, which could provide clues to how life started on Earth.[18] Any life detected at the remote ocean worlds in the outer Solar System would likely have formed and evolved along an independent path from life on Earth, giving us a deeper understanding of the potential for life in the universe.[4]

Oceanographers, biologists and astrobiologists are part of the team developing the strategy roadmap.[3] The planning also considers implementing planetary protection measures to avoid contaminating extraterrestrial habitable environments with resilient stowaway bacteria on their landers.[3][4]

Targets

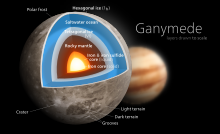

[edit]Ocean worlds identified in the Solar System so far with reasonable certainty are the major moons Europa, Enceladus, Titan, Ganymede, and Callisto.[5] Of these, Europa and Enceladus have the highest priority because their icy shells are thinner than the others (Enceladus’ is less than 10 km; Europa's is about 40 km) and there is some evidence their oceans are in contact with the rocky mantle, which could provide both energy and chemicals for life to form.[5] Enceladus' ice crust has fractures at the south pole that allow ice and gas from the ocean to escape to space, where it has been sampled by mass spectrometers aboard the Cassini Saturn orbiter with tantalizing results.[19] Titan's ocean is the deepest, at 50 to 100 km, and no evidence for active plumes or ice volcanism have been observed.

Bodies such as Triton, Pluto, Ceres, Miranda, Ariel, and Dione are considered candidate ocean worlds, based on hints from limited spacecraft observations.[5]

Missions

[edit]The Ocean Worlds Exploration Program (OWEP) is supporting the Europa Clipper orbiter mission to Europa, which is the first planned target of this program to be launched in 2024.[3][6] The second is the Dragonfly mission to Titan.[5]

The program is also supporting concept studies for a proposed Europa Lander,[7] and a concept to explore the moon Triton with Trident, a mission selected as a finalist in NASA's Discovery Program in 2020.[8][5]

See also

[edit]Astrobiology mission concepts to water worlds in the outer Solar System:

- Enceladus Explorer (EnEx) – Planned interplanetary orbiter and lander mission

- Enceladus Life Finder (ELF) – Proposed NASA mission to a moon of Saturn

- Enceladus Life Signatures and Habitability (ELSAH) – Astrobiology concept mission

- Enceladus Orbilander – Proposed NASA space probe to Saturn's moon Enceladus

- Explorer of Enceladus and Titan (E2T) – NASA/ESA Saturnian moon probe concept

- Journey to Enceladus and Titan (JET) – Proposed space mission

- Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) – European mission to study Jupiter and its moons since 2023

- Laplace-P – Proposed Russian spacecraft to study the Jovian moon system and land on Ganymede

- Life Investigation For Enceladus (LIFE) – Proposed astrobiology mission

- Neptune Odyssey – NASA orbiter mission concept to study the Neptune system

- Oceanus (Titan orbiter) – 2017 proposed NASA Triton orbiter space probe

- Testing the Habitability of Enceladus's Ocean (THEO) – Orbiter mission to Enceladus

- Titan Lake In-situ Sampling Propelled Explorer (TALISE) – Proposed space mission

- Titan Mare Explorer (TiME) – Proposed spacecraft lander design

- Trident – NASA space probe proposal to study the ice giant planet Neptune and its moon Triton

- Triton Hopper – Proposed NASA Triton lander space probe

References

[edit]- ^ Implementable program for efficient ocean-world exploration. Sherwood, Brent; Sotin, Christophe; Lunine, Jonathan; Cwik, Tom. 42nd COSPAR Scientific Assembly. Held 14–22 July 2018, in Pasadena, California, USA, Abstract id. B5.3-5-18.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (14 April 2017). ""Ocean Worlds" discoveries build case for new missions". Space News. Retrieved 2017-09-30.

- ^ a b c d e f McEwen, Alfred (1 February 2016). "Roadmaps to Ocean Worlds (ROW)" (PDF). Lunar and Planetary Institute. Retrieved 2017-09-30.

- ^ a b c "NASA's plans to explore Europa and other "ocean worlds"". Universe Today. PhysOrg. 6 March 2017. Retrieved 2017-09-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j The NASA Roadmap to Ocean Worlds. Amanda R. Hendrix, Terry A. Hurford, Laura M. Barge, Michael T. Bland, Jeff S. Bowman, William Brinckerhoff, Bonnie J. Buratti, Morgan L. Cable, Julie Castillo-Rogez, Geoffrey C. Collins, etal. Astrobiology, Vol. 19, No. 1. doi:10.1089/ast.2018.1955

- ^ a b c "NASA's FY2016 Budget Request" (PDF). Space Policy Online. 27 May 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-07-31. Retrieved 2017-09-30.

In fact, the report accompanying the bill directs NASA to create an "Ocean Worlds Exploration Program" of which the Europa mission is part.

- ^ a b Europa Lander. Home Page at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) NASA. Accessed on 22 September 2019.

- ^ a b Brown, David W. (19 March 2019). "Neptune's Moon Triton Is Destination of Proposed NASA Mission". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ^ Fish, Tom (5 March 2019). "NASA Ocean Worlds mission: NASA's space program to search for alien life". UK Express.

- ^ Hsu, Hsiang-Wen; Postberg, Frank; et al. (March 11, 2015). "Ongoing hydrothermal activities within Enceladus". Nature. 519 (7542): 207–10. Bibcode:2015Natur.519..207H. doi:10.1038/nature14262. PMID 25762281. S2CID 4466621.

- ^ Wenz, John (19 May 2015). "NASA Wants to go Underwater Exploring on Ocean Moons". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 2017-09-30.

- ^ Berger, Eric (19 May 2015). "The House budget for NASA plants the seeds of a program to finally find life in the outer solar system". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2017-09-30.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (22 August 2019). "Europa Clipper passes key review". Space News.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (17 February 2019). "Final fiscal year 2019 budget bill secures $21.5 billion for NASA". Space News.

- ^ a b FOLLOW THE (OUTER SOLAR SYSTEM) WATER: PROGRAM OPTIONS TO EXPLORE OCEAN WORLDS. (PDF). B. Sherwood, J. Lunine, C. Sotin, T. Cwik1, F. Naderi. Planetary Science Vision 2050 Workshop 2017.

- ^ Amanda R. Hendrix; Terry A. Hurford; et al. (January 1, 2019). "The NASA Roadmap to Ocean Worlds". Astrobiology. 19 (1): 1–27. Bibcode:2019AsBio..19....1H. doi:10.1089/ast.2018.1955. PMC 6338575. PMID 30346215.

- ^ Creech, Stephen D; Vane, Greg. "Ocean World Exploration and SLS: Enabling the Search for Life". Nasa Technical Reports Server. NASA. Retrieved 2017-09-30.

- ^ Anderson, Paul Scott (15 May 2015). "'Ocean Worlds Exploration Program': New Budget Proposal Calls for Missions to Europa, Enceladus, and Titan". AmericaSpace. Retrieved 2017-09-30.

- ^ Postberg, Frank; et al. (June 27, 2018). "Macromolecular organic compounds from the depths of Enceladus". Nature. 558 (7711): 564–568. Bibcode:2018Natur.558..564P. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0246-4. PMC 6027964. PMID 29950623.