Life Investigation For Enceladus

This article needs to be updated. (August 2024) |

Life Investigation For Enceladus (LIFE) was a proposed astrobiology mission concept that would capture icy particles from Saturn's moon Enceladus and return them to Earth, where they could be studied in detail for signs of life such as biomolecules.[1][2][3][4]

The LIFE orbiter concept was proposed by a team led by Peter Tsou to NASA's 13th Discovery Mission solicitation,[3] but the mission was not selected by NASA for Phase-A design study.[5]

Mission concept

[edit]

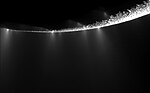

Enceladus is a small icy moon with jets or geysers of water erupting from its surface that might be connected to active hydrothermal vents at its subsurface water ocean floor,[6][7][8][9][10] where the moon's ocean meets the underlying rock, a prime habitat for life.[11][12] The geysers could provide easy access for sampling the moon's subsurface ocean, and if there is microbial life in it, ice particles from the sea could contain the evidence astrobiologists need to identify them.[13][14]

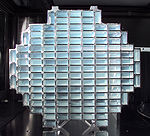

The 15-year LIFE mission would use a 'Tanpopo' aerogel collector[14] similar to the one NASA used in the Stardust sample return mission to return cometary dust in 2006. The proposed spacecraft would enter into Saturn orbit and enable multiple flybys through Enceladus's icy plumes. After spending about two years in orbit as slow as 2 km/s around Saturn,[2] LIFE would use its propulsion system to escape Saturn and begin the ~4.5 year long voyage back to Earth with the collected particles in a return capsule.[15][16] The spacecraft may sample Enceladus's plume, the E ring of Saturn, and the Titan upper atmosphere.[2]

In December 2014, NASA announced that it would be selecting finalists in June 2015 to submit proposals for a future Discovery Program mission, and selecting a winning proposal in September 2016. The selected mission must launch by the end of 2021.[17] The mission would have a $425 million development cost cap, and it would reach Saturn after a series of gravity assists past Venus and the Earth. Samples from Enceladus's plume would make it to Earth about 14 years later.[1] In September 2016, NASA announced that five proposals had been selected for further study.[18][needs update]

Science payload

[edit]

As currently envisioned, the probe's science payload would consist of:[1]

- an aerogel collector — for capture of particles at 2 km/s [2][14]

- a tool for collecting volatile chemicals

- a mass spectrometer —CHIMPS, an upgraded ROSINA on Rosetta spacecraft

- a camera — optical navigation shared with science to observe the dynamics of the jets

- a dust counter — to confirm the flux of the jet particles encountered by the collectors

The samples collected would be returned to Earth for extensive analyses.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Wall, Mike (December 6, 2012). "Saturn Moon Enceladus Eyed for Sample-Return Mission". Space.com. Retrieved 2015-04-10.

- ^ a b c d Tsou, Peter; Brownlee, D.E.; McKay, Christopher; Anbar, A.D.; Yano, H. (August 2012). "LIFE: Life Investigation For Enceladus A Sample Return Mission Concept in Search for Evidence of Life". Astrobiology. 12 (8): 730–742. Bibcode:2012AsBio..12..730T. doi:10.1089/ast.2011.0813. PMID 22970863. S2CID 34375065.

- ^ a b Tsou, Peter; Anbar, Ariel; Atwegg, Kathrin; Porco, Carolyn; Baross, John; McKay, Christopher (2014). "LIFE - Enceladus Plume Sample Return via Discovery" (PDF). 45th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. Retrieved 2015-04-10.

- ^ Tsou, Peter (2013). "LIFE: Life Investigation For Enceladus - A Sample Return Mission Concept in Search for Evidence of Life". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 12 (8): 730–42. doi:10.1089/ast.2011.0813. PMID 22970863. Archived from the original (.doc) on 2015-09-01. Retrieved 2015-04-10.

- ^ "NASA announces five Discovery proposals selected for further study". The Planetary Society. September 30, 2015. Retrieved 2017-01-02.

- ^ Ocean Within Enceladus May Harbor Hydrothermal Activity. March 11, 2015.

- ^ Platt, Jane; Bell, Brian (April 3, 2014). "NASA Space Assets Detect Ocean inside Saturn Moon". NASA. Retrieved 2014-04-03.

- ^ Iess, L.; Stevenson, D. J.; Parisi, M.; Hemingway, D.; Jacobson, R.A.; Lunine, Jonathan I.; Nimmo, F.; Armstrong, J. W.; Asmar, S. W.; Ducci, M.; Tortora, P. (April 4, 2014). "The Gravity Field and Interior Structure of Enceladus" (PDF). Science. 344 (6179): 78–80. Bibcode:2014Sci...344...78I. doi:10.1126/science.1250551. PMID 24700854. S2CID 28990283.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (April 3, 2014). "Saturn's Enceladus moon hides 'great lake' of water". BBC News. Retrieved 2014-04-07.

- ^ Kane, Van (3 April 2014). "Discovery Missions for an Icy Moon with Active Plumes". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 2015-04-09.

- ^ Witze, Alexandra (March 11, 2015). "Hints of hot springs found on Saturnian moon". Nature News. Retrieved 2015-04-07.

- ^ Anderson, Paul Scott (March 13, 2015). "Cassini Finds Evidence for Hydrothermal Activity on Saturn's Moon Enceladus". AmericaSpace. Retrieved 2015-04-07.

- ^ Gronstal, Aaron (July 30, 2014). "Enceladus in 101 Geysers". NASA Astrobiology Institute. Archived from the original on August 16, 2014. Retrieved 2015-04-08.

- ^ a b c Yano, H.; Strange, Nathan; Dissly, Richard; Kanik, I. (June 18, 2013). Tsou, Peter; Brownlee, D. E.; McKay, C. P.; et al. (eds.). Low Cost Enceladus Sample Return Mission Concept (PDF). Low Cost Planetary Missions Conference #10. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 8, 2014. Retrieved April 10, 2015.

- ^ Gilster, Paul (May 28, 2014). "Proposed Europa/Io Sample Return Mission". Centauri Dreams. Retrieved 2015-04-10.

- ^ LePage, Drew (March 27, 2014). "A Europa-Io Sample Return Mission". Drew ExMachina. Retrieved 2015-04-10.

- ^ Kane, Van (December 2, 2014). "Selecting the Next Creative Idea for Exploring the Solar System". Planetary Society. Retrieved 2015-02-10.

- ^ Dreier, Casey; Lakdawalla, Emily (December 2, 2014). "Selecting the Next Creative Idea for Exploring the Solar System". Planetary Society. Retrieved 2015-02-10.