Sabra and Shatila massacre

| Sabra and Shatila massacre | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Lebanese Civil War | |

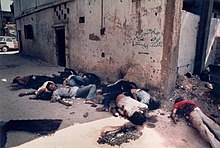

Bodies of victims of the massacre in the Sabra neighbourhood and Shatila refugee camp[1] | |

Site of the attack in Lebanon | |

| Location | Beirut, Lebanon |

| Coordinates | 33°51′46″N 35°29′54″E / 33.8628°N 35.4984°E |

| Date | 16–18 September 1982 |

| Target | Sabra neighbourhood and the Shatila refugee camp |

Attack type | Massacre |

| Deaths | 1,300 to 3,500+ |

| Victims | Palestinians and Lebanese Shias |

| Perpetrators | |

The Sabra and Shatila massacre was the 16–18 September 1982 killing of between 1,300 and 3,500 civilians—mostly Palestinians and Lebanese Shias—in the city of Beirut during the Lebanese Civil War. It was perpetrated by the Lebanese Forces, one of the main Christian militias in Lebanon, and supported by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) that had surrounded Beirut's Sabra neighbourhood and the adjacent Shatila refugee camp.[2]

In June 1982, Israel invaded Lebanon with the intention of rooting out the PLO. By 30 August 1982, under the supervision of the Multinational Force, the PLO withdrew from Lebanon following weeks of battles in West Beirut and shortly before the massacre took place. Various forces—Israeli, Lebanese Forces and possibly also the South Lebanon Army (SLA)—were in the vicinity of Sabra and Shatila at the time of the slaughter, taking advantage of the fact that the Multinational Force had removed barracks and mines that had encircled Beirut's predominantly Muslim neighborhoods and kept the Israelis at bay during the siege of Beirut.[3] The Israeli advance over West Beirut in the wake of the PLO withdrawal, which enabled the Lebanese Forces raid, was in violation of the ceasefire agreement between the various forces.[4]

The killings are widely believed to have taken place under the command of Lebanese politician Elie Hobeika, whose family and fiancée had been murdered by Palestinian militants and left-wing Lebanese militias during the Damour massacre in 1976, itself a response to the Karantina massacre of Palestinians and Lebanese Shias at the hands of Christian militias.[5][6][7][8] In total, between 300 and 400 militiamen were involved in the massacre, including some from the South Lebanon Army.[9] As the massacre unfolded, the IDF received reports of atrocities being committed, but did not take any action to stop it.[10] Instead, Israeli troops were stationed at the exits of the area to prevent the camp's residents from leaving and, at the request of the Lebanese Forces,[11] shot flares to illuminate Sabra and Shatila through the night during the massacre.[12][13]

In February 1983, an independent commission chaired by Irish diplomat Seán MacBride, assistant to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, concluded that the IDF, as the then occupying power over Sabra and Shatila, bore responsibility for the militia's massacre.[14] The commission also stated that the massacre was a form of genocide.[15] And in February 1983, the Israeli Kahan Commission found that Israeli military personnel had failed to take serious steps to stop the killings despite being aware of the militia's actions, and deemed that the IDF was indirectly responsible for the events, and forced erstwhile Israeli defense minister Ariel Sharon to resign from his position "for ignoring the danger of bloodshed and revenge" during the massacre.[16]

Background

Lebanese Civil War and Israeli-PLO skirmishes

From 1975 to 1990, groups in competing alliances with neighboring countries fought against each other in the Lebanese Civil War. Infighting and massacres between these groups claimed several thousand victims. Examples: the Syrian-backed Karantina massacre (January 1976) by the Kataeb and its allies against Kurds, Syrians and Palestinians in the predominantly Muslim slum district of Beirut; Damour (January 1976) by the PLO against Christian Maronites, including the family and fiancée of the Lebanese Forces intelligence chief Elie Hobeika; and Tel al-Zaatar (August 1976) by Phalangists and their allies against Palestinian refugees living in a camp administered by UNRWA. The total death toll in Lebanon for the whole civil war period was around 150,000 victims.[17]

As the civil war unfolded, Israel and the PLO had been exchanging attacks since the early 1970s until early 1980s.[18]

The casus belli cited by the Israeli side to declare war, however, was an assassination attempt, on 3 June 1982, made upon Israeli Ambassador to Britain Shlomo Argov. The attempt was the work of the Iraq-based Abu Nidal, possibly with Syrian or Iraqi involvement.[19][20] Historians and observers[21][22] such as David Hirst and Benny Morris have commented that the PLO could not have been involved in the assault, or even approved of it, as Abu Nidal's group was a bitter rival to Arafat's PLO and even murdered some of its members.[23] The PLO issued a condemnation of the attempted assassination of the Israeli ambassador.[23] Nonetheless, Israel used the event as a justification to break the ceasefire with the PLO, and as a casus belli for a full-scale invasion of Lebanon.[24][25]

Post-war assessment

After the war, Israel presented its actions as a response to terrorism being carried out by the PLO from several fronts, including the border with Lebanon.[26][27] However, these historians have argued that the PLO was respecting the ceasefire agreement then in force with Israel and keeping the border between the Jewish state and Lebanon more stable than it had been for over a decade.[28] During that ceasefire, which lasted eight months, UNIFIL—the UN peacekeeping forces in Lebanon—reported that the PLO had launched not a single act of provocation against Israel.[29] The Israeli government tried out several justifications to ditch the ceasefire and attack the PLO, even eliciting accusations from the Israeli opposition that "demagogy" from the government threatened to pull Israel into war.[29] Before the attempted assassination of the ambassador, all such justifications had been shot down by its ally, the United States, as an insufficient reason to launch a war against the PLO.[29]

On 6 June 1982, Israel invaded Lebanon moving northwards to surround the capital, Beirut.[30] Following an extended siege of the city, the fighting was brought to an end with a U.S.-brokered agreement between the parties on 21 August 1982, which allowed for safe evacuation of the Palestinian fighters from the city under the supervision of Western nations and guaranteed the protection of refugees and the civilian residents of the refugee camps.[30]

On 15 June 1982, 10 days after the start of the invasion, the Israeli Cabinet passed a proposal put forward by the Prime Minister, Menachem Begin, that the IDF should not enter West Beirut but this should be done by Lebanese Forces. Chief of Staff, Rafael Eitan, had already issued orders that the Lebanese predominantly Christian, right-wing militias should not take part in the fighting and the proposal was to counter public complaints that the IDF were suffering casualties whilst their allies were standing by.[31] The subsequent Israeli inquiry estimated the strength of militias in West Beirut, excluding Palestinians, to be around 7,000. They estimated the Lebanese Forces to be 5,000 when fully mobilized of whom 2,000 were full-time.[32]

On 23 August 1982, Bachir Gemayel, leader of the right-wing Lebanese Forces, was elected President of Lebanon by the National Assembly. Israel had relied on Gemayel and his forces as a counterbalance to the PLO, and as a result, ties between Israel and Maronite groups, from which hailed many of the supporters of the Lebanese Forces, had grown stronger.[33][34][35]

By 1 September, the PLO fighters had been evacuated from Beirut under the supervision of Multinational Force.[4][36] The evacuation was conditional on the continuation of the presence of the Multinational Force in Lebanon (MNF) to provide security for the community of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon.[4] Two days later the Israeli Premier Menachem Begin met Gemayel in Nahariya and strongly urged him to sign a peace treaty with Israel. Begin also wanted the continuing presence of the SLA in southern Lebanon (Haddad supported peaceful relations with Israel) in order to control attacks and violence, and action from Gemayel to move on the PLO fighters which Israel believed remained a hidden threat in Lebanon. However, the Phalangists, who were previously united as reliable Israeli allies, were now split because of developing alliances with Syria, which remained militarily hostile to Israel. As such, Gemayel rejected signing a peace treaty with Israel and did not authorize operations to root out the remaining PLO militants.[37]

On 11 September 1982, the international forces that were guaranteeing the safety of Palestinian refugees left Beirut. Then on 14 September, Gemayel was assassinated in a massive explosion which demolished his headquarters. Eventually, the culprit, Habib Tanious Shartouni, a Lebanese Christian, confessed to the crime. He turned out to be a member of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party and an agent of Syrian intelligence. Palestinian and Lebanese Muslim leaders denied any connection to him.[38]

On the evening of 14 September, following the news that Bachir Gemayel had been assassinated, Prime Minister Begin, Defense Minister Sharon and Chief of Staff Eitan agreed that the Israeli army should invade West Beirut. The public reason given was to be that they were there to prevent chaos. In a separate conversation, at 20:30 that evening, Sharon and Eitan agreed that the IDF should not enter the Palestinian refugee camps but that the Phalange should be used.[39] The only other member of the cabinet who was consulted was Foreign Minister Yitzhak Shamir.[40] Shortly after 6.00 am 15 September, the Israeli army entered West Beirut,[41] This Israeli action breached its agreement with the United States not to occupy West Beirut[42] and was in violation of the ceasefire.[43]

Fawwaz Traboulsi writes that while the massacre was presented as a reaction to the assassination of Bachir, it represented the posthumous achievement of his "radical solution" to Palestinians in Lebanon, who he thought of as "people too many" in the region. Later, the Israeli army's monthly journal Skira Hodechith wrote that the Lebanese Forces hoped to provoke "the general exodus of the Palestinian population" and aimed to create a new demographic balance in Lebanon favouring the Christians.[44]

Attack

Lead-up events

On the night of 14/15 September 1982 the IDF chief of staff Raphael Eitan flew to Beirut where he went straight to the Phalangists' headquarters and instructed their leadership to order a general mobilisation of their forces and prepare to take part in the forthcoming Israeli attack on West Beirut. He also ordered them to impose a general curfew on all areas under their control and appoint a liaison officer to be stationed at the IDF forward command post. He told them that the IDF would not enter the refugee camps but that this would be done by the Phalangist forces. The militia leaders responded that the mobilisation would take them 24 hours to organise.[45]

On morning of Wednesday 15 September Israeli Defence Minister, Sharon, who had also travelled to Beirut, held a meeting with Eitan at the IDF's forward command post, on the roof of a five-storey building 200 metres southwest of Shatila camp. Also in attendance were Sharon's aide Avi Duda'i, the Director of Military Intelligence -Yehoshua Saguy, a senior Mossad officer, General Amir Drori, General Amos Yaron, an Intelligence officer, the Head of GSS—Avraham Shalom, the Deputy Chief of Staff—General Moshe Levi and other senior officers. It was agreed that the Phalange should go into the camps.[45] According to the Kahan Commission report throughout Wednesday, R.P.G. and light-weapons fire from the Sabra and Shatila camps was directed at this forward command post, and continued to a lesser degree on Thursday and Friday (16–17 September). It also added that by Thursday morning, the fighting had ended and all was 'calm and quiet'.[46]

Following the assassination of Lebanese Christian President Bachir Gemayel, the Phalangists sought revenge. By noon on 15 September, Sabra and Shatila had been surrounded by the IDF, which set up checkpoints at the exits and entrances, and used several multi-story buildings as observation posts. Amongst them was the seven-story Kuwaiti embassy which, according to Time magazine, had "an unobstructed and panoramic view" of Sabra and Shatila. Hours later, IDF tanks began shelling Sabra and Shatila.[40]

The following morning, 16 September, the sixth IDF order relating to the attack on West Beirut was issued. It specified: "The refugee camps are not to be entered. Searching and mopping up the camps will be done by the Phalangists/Lebanese Army".[47]

According to Linda Malone of the Jerusalem Fund, Ariel Sharon and Chief of Staff Rafael Eitan[48] met with Phalangist militia units and invited them to enter Sabra and Shatila, claiming that the PLO was responsible for Gemayel's assassination.[49] The meeting concluded at 15:00 on 16 September.[40]

Shatila had previously been one of the PLO's three main training camps for foreign fighters and the main training camp for European fighters.[50] The Israelis maintained that 2,000 to 3,000 terrorists remained in the camps, but were unwilling to risk the lives of more of their soldiers after the Lebanese army repeatedly refused to "clear them out."[51] No evidence was offered for this claim. There were only a small number of forces sent into the camps and they suffered minimal casualties.[40]: 39 Two Phalangists were wounded, one in the leg and another in the hand.[52] Investigations after the massacre found few weapons in the camps.[40]: 39 [53] Thomas Friedman, who entered the camps on Saturday, mostly found groups of young men with their hands and feet bound, who had been then lined up and machine-gunned down gang-land style, not typical he thought of the kind of deaths the reported 2,000 terrorists in the camp would have put up with.[54]

Massacre

An hour later, 1,500 militiamen assembled at Beirut International Airport, then occupied by Israel. Under the command of Elie Hobeika, they began moving towards the area in IDF-supplied jeeps, some bearing weapons provided by Israel,[55] following Israeli guidance on how to enter it. The forces were mostly Phalangist, though there were some men from Saad Haddad's "Free Lebanon forces".[40] According to Ariel Sharon and Elie Hobeika's bodyguard, the Phalangists were given "harsh and clear" warnings about harming civilians.[42][56] However, it was by then known that the Phalangists presented a special security risk for Palestinians. It was published in the edition of 1 September of Bamahane, the IDF newspaper, that a Phalangist told an Israeli official: "[T]he question we are putting to ourselves is—how to begin, by raping or killing?"[57] A US envoy to the Middle East expressed horror after being told of Sharon's plans to send the Phalangists inside the camps, and Israeli officials themselves acknowledged the situation could trigger "relentless slaughter".[4]

The first unit of 150 Phalangists entered Sabra and Shatila at sunset on Thursday, 16 September. They entered the homes of the camp residents and began shooting and raping them, often taking groups outside and lining them up for execution.[40]: 40 During the night, the Israeli forces fired illuminating flares over the area. According to a Dutch nurse, the camp was as bright as "a sports stadium during a football game".[58]

At 19:30, the Israeli Cabinet convened and was informed that the Phalangist commanders had been informed that their men must participate in the operation and fight, and enter the extremity of Sabra, while the IDF would guarantee the success of their operation though not participate in it. The Phalangists were to go in there "with their own methods". After Gemayel's assassination there were two possibilities, either the Phalange would collapse or they would undertake revenge, having killed Druze for that reason earlier that day. With regard to this second possibility, it was noted, 'it will be an eruption the likes of which has never been seen; I can already see in their eyes what they are waiting for.' 'Revenge' was what Bachir Gemayel's brother had called for at the funeral earlier. Levy commented: 'the Phalangists are already entering a certain neighborhood—and I know what the meaning of revenge is for them, what kind of slaughter. Then no one will believe we went in to create order there, and we will bear the blame. Therefore, I think that we are liable here to get into a situation in which we will be blamed, and our explanations will not stand up ..."[59] The press release that followed reads:

In the wake of the assassination of the President-elect Bashir Jemayel, the I.D.F. has seized positions in West Beirut in order to forestall the danger of violence, bloodshed and chaos, as some 2,000 terrorists, equipped with modern and heavy weapons, have remained in Beirut, in flagrant violation of the evacuation agreement.

An Israeli intelligence officer present in the forward post, wishing to obtain information about the Phalangists' activities, ordered two distinct actions to find out what was happening. The first failed to turn up anything. The second resulted in a report at 20:00 from the roof, stated that the Phalangists' liaison officer had heard from an operative inside the camp that he held 45 people and asked what he should do with him. The liaison officer told him to more or less "Do the will of God." The Intelligence Officer received this report at approximately 20:00 from the person on the roof who heard the conversation. He did not pass on the report.[60]

At roughly the same time or a little earlier at 19:00, Lieutenant Elul testified that he had overheard a radio conversation between one of the militia men in the camp and his commander Hobeika in which the former asking what he was to do with 50 women and children who had been taken prisoner. Hobeika's reply was: "This is the last time you're going to ask me a question like that; you know exactly what to do." Other Phalangists on the roof started laughing. Amongst the Israelis there was Brigadier General Yaron, Divisional Commander, who asked Lieutenant Elul, his Chef de Bureau, what the laughter was about; Elul translated what Hobeika had said. Yaron then had a five-minute conversation, in English, with Hobeika. What was said is unknown.[42][60]

The Kahan Commission determined that the evidence pointed to 'two different and separate reports', noting that Yaron maintained that he thought they referred to the same incident, and that it concerned 45 "dead terrorists". At the same time, 20:00, a third report came in from liaison officer G. of the Phalangists who in the presence of numerous Israeli officers, including general Yaron, in the dining room, stated that within 2 hours the Phalangists had killed 300 people, including civilians. He returned sometime later and changed the number from 300 to 120.[52]

At 20:40, General Yaron held a briefing, and after it the Divisional Intelligence Officer stated that it appeared no terrorists were in the Shatila camp, and that the Phalangists were in two minds as to what to do with the women, children and old people they had massed together, either to lead them somewhere else or that they were told, as the liaison officer was overheard saying, to 'do what your heart tells you, because everything comes from God.' Yaron interrupted the officer and said he'd checked and that 'they have no problems at all,' and that with regard to the people, 'It will not, will not harm them.' Yaron later testified he had been sceptical of the reports and had in any case told the Phalangists not to harm civilians.[61] At 21:00 Maj. Amos Gilad predicted during a discussion at Northern Command that, rather than a cleansing of terrorists, what would take place was a massacre, informing higher commanders that already between 120 and 300 had already been killed by that time.[62]

At 23:00 the same evening, a report was sent to the IDF headquarters in East Beirut, reporting the killings of 300 people, including civilians. The report was forwarded to headquarters in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, and to the office of the Bureau Chief of the director of Military Intelligence, Lt. Col. Hevroni, at 05:30 the following day where it was seen by more than 20 senior Israeli officers. It was then forwarded to his home by 06:15.[40][63] That same morning an IDF historian copied down a note, which later disappeared, which he had found in the Northern Command situation room in Aley.

During the night the Phalangists entered the Sabra and Shatilla refugee camps. Even though it was agreed that they would not harm civilians, they 'butchered.' They did not operate in orderly fashion but dispersed. They had casualties, including two killed. They will organize to operate in a more orderly manner—we will see to it that they are moved into the area."[64]

Early on that morning, between 08:00 and 09:00, several IDF soldiers stationed nearby noted killings were being conducted against the camp refugees. A deputy tank commander some 180 metres (200 yd) away, Lieutenant Grabowski, saw two Phalangists beating two young men, who were then taken back into the camp, after which shots rang out, and the soldiers left. Sometime later, he saw the Phalangists had killed a group of five women and children. When he expressed a desire to make report, the tank crew said they had already heard a communication informing the battalion commander that civilians had been killed, and that the latter had replied, "We know, it's not to our liking, and don't interfere."[65]

At around 08:00, military correspondent Ze'ev Schiff received a tip-off a source in the General Staff in Tel Aviv that there had been a slaughter in the camps. Checking round for some hours, he got no confirmation other than that there "there's something." At 11:00 he met with Mordechai Tzipori, Minister of Communications and conveyed his information. Unable to reach Military Intelligence by phone, he got in touch with Yitzhak Shamir at 11:19 asking him to check reports of a Phalangist slaughter in the camps.[66][page needed] Shamir testified that from his recollection the main thing Tzipori had told him of was that 3/4 IDF soldiers killed, no mention of a massacre or slaughter, as opposed to a "rampage" had been made. He made no check because his impression was that the point of the information was to keep him updated on IDF losses.[67] At a meeting with American diplomats at 12:30 Shamir made no mention of what Tzipori told him, saying he expected that he would hear from Ariel Sharon, the Military Intelligence chief and the American Morris Draper about the situation in West Beirut,[65] At that noontime meeting Sharon insisted that "terrorists" needed "mopping up."[4] Americans pressed for the intervention of the Lebanese National Army, and for an IDF withdrawal immediately. Sharon replied:

I just don't understand, what are you looking for? Do you want the terrorists to stay? Are you afraid that somebody will think that you were in collusion with us? Deny it. We denied it,[4]

adding that nothing would happen except perhaps for a few more terrorists being killed, which would be a benefit to all. Shamir and Sharon finally agreed to a gradual withdrawal, at the end of Rosh Hashana, two days later. Draper then warned them:

Sure, the I.D.F. is going to stay in West Beirut and they will let the Lebanese go and kill the Palestinians in the camps.[4]

Sharon replied:

So, we'll kill them. They will not be left there. You are not going to save them. You are not going to save these groups of the international terrorism.. . If you don't want the Lebanese to kill them, we will kill them.[4]

In the afternoon, before 16:00, Lieutenant Grabowski had one of his men ask a Phalangist why they were killing civilians, and was told that pregnant women will give birth to children who will grow up to be terrorists.[65]

At Beirut airport at 16:00 journalist Ron Ben-Yishai heard from several Israeli officers that they had heard that killings had taken place in the camps. At 11:30 he telephoned Ariel Sharon to report on the rumours, and was told by Sharon that he had already heard of the stories from the Chief of Staff.[66][page needed] At 16:00 in a meeting with the Phalangist staff, with Mossad present, the Israeli Chief of Staff said he had a "positive impression" of their behavior in the field and from what the Phalangists reported, and asked them to continue 'mopping up the empty camps' until 5 am, whereupon they must desist due to American pressure. According to the Kahan Commission investigation, neither side explicitly mentioned to each other reports or rumours about the way civilians were being treated in the camp.[66][page needed] Between 18:00 and 20:00, Israeli Foreign Ministry personnel in Beirut and in Israel began receiving various reports from U.S. representatives that the Phalangists had been observed in the camps and that their presence was likely to cause problems. On returning to Israel, the Chief of Staff spoke to Ariel Sharon between 20:00 and 21:00, and according to Sharon, informed him that the "Lebanese had gone too far", and that "the Christians had harmed the civilian population more than was expected." This, he testified, was the first he had ever heard of Phalangist irregularities in the camps.[68] The Chief of Staff denied they had discussed any killings "beyond what had been expected".[68]

Later in the afternoon, a meeting was held between the Israeli Chief of Staff and the Phalangist staff.

On the morning of Friday, 17 September, the Israeli Army surrounding Sabra and Shatila ordered the Phalange to halt their operation, concerned about reports of a massacre.[42]

Foreign reporters' testimonies

On 17 September, while Sabra and Shatila still were sealed off, a few independent observers managed to enter. Among them were a Norwegian journalist and diplomat Gunnar Flakstad, who observed Phalangists during their cleanup operations, removing dead bodies from destroyed houses in the Shatila camp.[69]

Many of the bodies found had been severely mutilated. Young men had been castrated, some were scalped, and some had the Christian cross carved into their bodies.[70]

Janet Lee Stevens, an American journalist, later wrote to her husband, Dr. Franklin Lamb, "I saw dead women in their houses with their skirts up to their waists and their legs spread apart; dozens of young men shot after being lined up against an alley wall; children with their throats slit, a pregnant woman with her stomach chopped open, her eyes still wide open, her blackened face silently screaming in horror; countless babies and toddlers who had been stabbed or ripped apart and who had been thrown into garbage piles."[71]

Before the massacre, it was reported that the leader of the PLO, Yasir Arafat, had requested the return of international forces, from Italy, France and the United States, to Beirut to protect civilians. Those forces had just supervised the departure of Arafat and his PLO fighters from Beirut. Italy expressed 'deep concerns' about 'the new Israeli advance', but no action was taken to return the forces to Beirut.[72] The New York Times reported in September 1982:

Yasir Arafat, leader of the Palestine Liberation Organization, demanded today that the United States, France and Italy send their troops back to Beirut to protect its inhabitants against Israel...The dignity of three armies and the honor of their countries is involved, Mr. Arafat said at his news conference. I ask Italy, France and the United States: What of your promise to protect the inhabitants of Beirut?

In interviews with film director Lokman Slim in 2005, some of the Lebanese Christian militia fighters reported that, prior to the massacre, the IDF took them to training camps in Israel and showed them documentaries about the Holocaust.[73] The Israelis told the Lebanese fighters that the same would happen to them too, as a minority in Lebanon, if the fighters did not take action against the Palestinians.[73] The film was called "Massaker", it featured six perpetrators of the Sabra and Shatila massacre, and it was awarded the Fipresci Prize at the 2005 Berlinale.[74]

Number of victims

- Palestinian Red Crescent estimated that over 2,000 had been killed. 1,200 death certificates were issued to anyone who produced three witnesses claiming a family member disappeared during the time of the massacre.[75]

- Bayan Nuwayhed al-Hout in her Sabra and Shatila: September 1982 gives a minimum consisting of 1,300 named victims based on detailed comparison of 17 victim lists and other supporting evidence, and estimates an even higher total of 3500.[76]

- Robert Fisk wrote, "After three days of rape, fighting and brutal executions, militias finally leave the camps with 1,700 dead".[77]

- In his book published soon after the massacre, the Israeli journalist Amnon Kapeliouk of Le Monde Diplomatique, arrived at about 2,000 bodies disposed of after the massacre from official and Red Cross sources and "very roughly" estimated 1,000 to 1,500 other victims disposed of by the Phalangists themselves to a total of 3,000–3,500.[78]

- The Lebanese army's chief prosecutor, Assad Germanos, investigated the killings, but following orders from above, did not summon Lebanese witnesses. Also Palestinian survivors from the camps were afraid to testify, and Phalangist fighters were expressly forbidden to give testimony. Germanos' report concluded that 460 people had been killed (including 15 women and 20 children.)

- Israeli intelligence estimated 700–800 dead.

Role of various parties

The primary responsibility for the massacre is generally attributed to Elie Hobeika. Robert Maroun Hatem, Elie Hobeika's bodyguard, stated in his book From Israel to Damascus that Hobeika ordered the massacre of civilians in defiance of Israeli instructions to behave like a "dignified" army.[56]

Hobeika was assassinated by a car bomb in Beirut on 24 January 2002. Lebanese and Arab commentators blamed Israel for the murder of Hobeika, with alleged Israeli motive that Hobeika would be "apparently poised to testify before the Belgian court about Sharon's role in the massacre"[79] (see section above). Prior to his assassination, Elie Hobeika had stated "I am very interested that the [Belgian] trial starts because my innocence is a core issue."[5]

According to Alain Menargues, on 15 September, an Israeli special operations group of Sayeret Matkal entered the camp to liquidate a number of Palestinian cadres, and left the same day. It was followed the next day, by "killers" from the Sa'ad Haddad's South Lebanon Army, before the Lebanese Forces units of Elie Hobeika entered the camps.[80][81][82]

The US responsibility was considerable;[83] indeed the Arab states and the PLO blamed the US.[84] The negotiations under the mediation of US diplomat Philip Habib, which oversaw the withdrawal of the PLO from Beirut, had assigned responsibility to the American-led Multi National Force for guaranteeing the safety of those non-combatant Palestinians who remained. The US administration was criticized for the early withdrawal of the Multi National Force, a criticism which George Shultz accepted later.[83] Shultz recounted in his memoirs that "The brutal fact is that we are partially responsible. We took the Israelis and Lebanese at their word".[85] On 20 September the Multi National Force was redeployed to Beirut.[83]

Aftermath

U.N. condemnation

On 16 December 1982, the United Nations General Assembly condemned the massacre and declared it to be an act of genocide.[86] The voting record[87][88][89] on section D of Resolution 37/123 was: yes: 123; no: 0; abstentions: 22; non-voting: 12.

The delegate for Canada stated: "The term genocide cannot, in our view, be applied to this particular inhuman act".[90] The delegate of Singapore – voting 'yes' – added: "My delegation regrets the use of the term 'an act of genocide' ... [as] the term 'genocide' is used to mean acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group." Canada and Singapore questioned whether the General Assembly was competent to determine whether such an event would constitute genocide.[91] The Soviet Union, by contrast, asserted that: "The word for what Israel is doing on Lebanese soil is genocide. Its purpose is to destroy the Palestinians as a nation."[92] The Nicaragua delegate asserted: "It is difficult to believe that a people that suffered so much from the Nazi policy of extermination in the middle of the twentieth century would use the same fascist, genocidal arguments and methods against other peoples."[90]

The United States commented that "While the criminality of the massacre was beyond question, it was a serious and reckless misuse of language to label this tragedy genocide as defined in the 1948 Convention".[93]

William Schabas, director of the Irish Centre for Human Rights at the National University of Ireland,[94] stated that "there was little discussion of the scope of the term genocide, which had obviously been chosen to embarrass Israel rather than out of any concern with legal precision".[90]

Irish Commission (MacBride)

The independent commission headed by Seán MacBride looking into reported violations of International Law by Israel, however, did find that the concept of genocide applied to the case as it was the intention of those behind the massacre "the deliberate destruction of the national and cultural rights and identity of the Palestinian people".[95] Individual Jews throughout the world also denounced the massacre as genocide.[15]

The MacBride Commission's report, Israel in Lebanon, concluded that the Israeli authorities or forces were responsible in the massacres and other killings that have been reported to have been carried out by Lebanese militiamen in Sabra and Shatila in the Beirut area between 16 and 18 September.[14] Unlike the Israeli commission, the McBride Commission did not work with the idea of separate degrees of responsibility, viz., direct and indirect.

Kahan Commission (Israel)

Israel's own Kahan commission found that only "indirect" responsibility befitted Israel's involvement. For British journalist David Hirst, Israel crafted the concept of indirect responsibility so as to make its involvement and responsibility seem smaller. He said of the commission's verdict that it was only by means of errors and omissions in the analysis of the massacre that the commission was able to reach the conclusion of indirect responsibility.[96][page needed]

The Kahan Commission concluded Israeli Defense minister Sharon bore personal responsibility "for ignoring the danger of bloodshed and revenge" and "not taking appropriate measures to prevent bloodshed". Sharon's negligence in protecting the civilian population of Beirut, which had come under Israeli control, amounted to a non-fulfilment of a duty with which the Defense Minister was charged, and it was recommended that Sharon be dismissed as Defense Minister.[97][16]

At first, Sharon refused to resign, and Begin refused to fire him. It was only after the death of Emil Grunzweig after a grenade was tossed by a right-wing Israeli into the dispersing crowd of a Peace Now protest march, which also injured ten others, that a compromise was reached: Sharon would resign as Defense Minister, but remain in the Cabinet as a minister without portfolio. Notwithstanding the dissuading conclusions of the Kahan report, Sharon would later become Prime Minister of Israel.[98][99]

The Kahan commission also recommended the dismissal of Director of Military Intelligence Yehoshua Saguy,[100][97] and the effective promotion freeze of Division Commander Brig. Gen. Amos Yaron for at least three years.[97]

On 25 September 1982, Peace Now, which had been established 4 years previously, organised in Tel Aviv a protest demonstration which brought to the streets some 10% of Israel’s population, an estimated 400,000 participants.[101] They expressed their anger and demanded an investigation into Israel's part and responsibility in the massacre.[101] It would remain Israel's largest street protest until the 2023 Israeli judicial reform protests[102] and 7 September 2024 rally for the liberation of hostages in exchange for a cease-fire deal with Hamas.[103]

An opinion poll indicated that 51.7% of the Israeli public thought the commission was too harsh, and only 2.17% too lenient.[104]

Post-war testimonies by Lebanese Forces operatives

Lokhman Slim and Monika Borgman's Massaker, based on 90 hours of interviews with the LF soldiers who participated in the massacre, gives the participants' memories of how they were drawn into the militia, trained with the Israeli army and unleashed on the camps to take revenge for the murder of Bachir Gemayel. The motivations are varied, from blaming beatings from their fathers in childhood, the effects of the brutalization of war, obedience to one's leaders, a belief that the camp women would breed future terrorists, and the idea three-quarters of the residents were terrorists. Others spoke of their violence without traces of repentance.[105]

Lawsuits against Sharon

Sharon's libel suit

Ariel Sharon sued Time magazine for libel in American and Israeli courts in a $50 million suit, after Time published a story in its 21 February 1983, issue, implying that Sharon had "reportedly discussed with the Gemayels the need for the Phalangists to take revenge" for Bachir's assassination.[106] The jury found the article false and defamatory, although Time won the suit in the U.S. court because Sharon's defense failed to establish that the magazine's editors and writers had "acted out of malice", as required under U.S. libel law.[107]

Relatives of victims sue Sharon

After Sharon's 2001 election as Israeli Prime Minister, relatives of the victims of the massacre filed a lawsuit.[108] On 24 September 2003, Belgium's Supreme Court dismissed the war crimes case against Ariel Sharon, since none of the plaintiffs had Belgian nationality at the start of the case.[109]

Reprisal attacks

According to Robert Fisk, Osama bin Laden cited the Sabra and Shatila massacre as one of the motivations for the 1996 Khobar Towers bombing, in which al-Qaeda attacked an American Air Force housing complex in Saudi Arabia.[110]

See also

- War of the Camps

- 1982 Hama massacre

- List of massacres in Lebanon

- Al-Manam, 1987 Syrian documentary taking place in Palestinian refugee camps prior to the massacre. Many of the subjects interviewed were killed in the massacre

- Waltz with Bashir, 2008 Israeli film by Ari Folman on events surrounding the massacre

References

- ^ "1982, Robin Moyer, World Press Photo of the Year, World Press Photo of the Year". archive.worldpressphoto.org. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ Fisk 2001, pp. 382–383; Quandt 1993, p. 266; Alpher 2015, p. 48; Gonzalez 2013, p. 113

- ^ Hirst 2010, p. 154.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Anziska, Seth (17 September 2012). "A Preventable Massacre". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 August 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ a b Mostyn, Trevor (25 January 2002). "Obituary: Elie Hobeika". The Guardian. guardian.co.uk. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ Friedman 1982. Also articles in The New York Times on the 20, 21, and 27 September 1982.

- ^ Harris, William W. (2006). The New Face of Lebanon: History's Revenge. Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-55876-392-0. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

the massacre of 1,500 Palestinians, Shi'is, and others in Karantina and Maslakh, and the revenge killings of hundreds of Christians in Damour

- ^ Hassan, Maher (24 January 2010). "Politics and war of Elie Hobeika". Egypt Independent. Archived from the original on 27 January 2023. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ Bulloch, John (1983). Final Conflict: The War in Lebanon. Century London. p. 231. ISBN 0-7126-0171-6.

- ^ Malone, Linda A. (1985). "The Kahan Report, Ariel Sharon and the Sabra Shatilla Massacres in Lebanon: Responsibility Under International Law for Massacres of Civilian Populations". Utah Law Review: 373–433. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ^ Hirst 2010, p. 157: "The carnage began immediately. It was to continue without interruption till Saturday noon. Night brought no respite; the Lebanses Forces liaison officer asked for illumination and the Israelis duly obliged with flares, first from mortars and then from planes."

- ^ Friedman, Thomas (1995). From Beirut to Jerusalem. Macmillan. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-385-41372-5.

From there, small units of Lebanese Forces militiamen, roughly 150 men each, were sent into Sabra and Shatila, which the Israeli army kept illuminated through the night with flares.

- ^ Cobban, Helena (1984). The Palestinian Liberation Organisation: people, power, and politics. Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-521-27216-2.

and while Israeli troops fired a stream of flares over the Palestinian refugee camps in the Sabra and Shatila districts of West Beirut, the Israeli's Christian Lebanese allies carried out a massacre of innocents there which was to shock the whole world.

- ^ a b MacBride et al. 1983, pp. 191–192.

- ^ a b Hirst 2010, p. 153.

- ^ a b Schiff & Ya'ari 1985, pp. 283–284.

- ^ Wood, Josh (12 July 2012). "After 2 Decades, Scars of Lebanon's Civil War Block Path to Dialogue". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 December 2023.

- ^ Metz, Helen Chapin, ed. (1988). "Israel in Lebanon". Israel: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

In July 1981 Israel responded to PLO rocket attacks on northern Israeli settlements by bombing PLO encampments in southern Lebanon. United States envoy Philip Habib eventually negotiated a shaky cease-fire that was monitored by UNIFIL.

- ^ Becker 1984, p. 362.

- ^ Schiff & Ya'ari 1985, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Fisk, Robert (25 October 2008). "Abu Nidal, notorious Palestinian mercenary, 'was a US spy'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 4 May 2024.

- ^ Cushman, Thomas; Cottee, Simon; Hitchens, Christopher (2008). Christopher Hitchens and His Critics: Terror, Iraq, and the Left. NYU Press. p. 300. ISBN 978-0814716878.

shlomo argov casus belli.

- ^ a b Hirst 2010, p. 134: "Clearly, the Israelis had just about dispensed with pretexts altogether. For form's sake, however, they did claim one for the launching of the Fifth Arab–Israeli war. The attempted assassination, on 3 June, of the Israeli ambassador in Britain, Shlomo Argov, was not the doing of the PLO, which promptly denounced it. It was another exploit of Arafat's arch-enemy, the notorious, Baghdad-based, Fatah dissident Abu Nidal ... the Israelis ignored such distinctions."

- ^ Bergman, Ahron (2002). Israel's Wars: A History since 1947 (Warfare and History). Routledge. pp. 158–159. ISBN 978-0415424387. Archived from the original on 8 October 2024. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ Gannon, James (2008). Military Occupations in the Age of Self-Determination: The History Neocons Neglected (Praeger Security International). Praeger. p. 162. ISBN 978-0313353826. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ Becker 1984, p. 257.

- ^ Israeli, Raphael (1983). PLO in Lebanon: Selected Documents. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 7. ISBN 0-297-78259-2.

From July 1981 to June 1982, under cover of the ceasefire, the PLO pursued its acts of terror against Israel, resulting in 26 deaths and 264 injured.

- ^ Morris, Benny (2001). Righteous Victims : A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881–2001. New York: Vintage Books. p. 509. ISBN 978-0-679-74475-7.

The most immediate problem was the PLO's military infrastructure, which posed a standing threat to the security of northern Israeli settlements. The removal of this threat was to be the battle cry to rouse the Israeli cabinet and public, despite the fact that the PLO took great pains not to violate the agreement of July 1981. Indeed, subsequent Israeli propaganda notwithstanding, the border between July 1981 and June 1982 enjoyed a state of calm unprecedented since 1968. But Sharon and Begin had a broader objective: the destruction of the PLO and its ejection from Lebanon. Once the organization was crushed, they reasoned, Israel would have a far freer hand to determine the fate of the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

- ^ a b c Hirst 2010, p. 133.

- ^ a b Nuwayhed al-Hout 2004, p. 1.

- ^ Kahan, Barak & Efrat 1983, p. 50.

- ^ Kahan, Barak & Efrat 1983, p. 6.

- ^ Eisenberg, Laura Zittrain; Caplan, Neil (1998). Negotiating Arab-Israeli Peace: Patterns, Problems, Possibilities. Indiana University Press. p. 45. ISBN 0-253-21159-X.

By 1982, the Israeli-Maronite relationship was quite the open secret, with Maronite militiamen training in Israel and high-level Maronite and Israeli leaders making regular reciprocal visits to one another's homes and headquarters"

- ^ "Sabra and Shatilla". Jewish Voice for Peace. Archived from the original on 30 October 2006. Retrieved 17 July 2006.

- ^ Asser, Martin (14 September 2002). "Sabra and Shatila 20 years on". BBC News. Archived from the original on 7 December 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2006.

- ^ "1982: PLO leader forced from Beirut". BBC News. 30 August 1982. Archived from the original on 21 June 2024. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ Bregman, Ahron; Al-Tahri, Jihan (1998). The Fifty Years War: Israel and the Arabs. London: BBC Books. pp. 172–174. ISBN 0-14-026827-8.

- ^ Walid Harb, Snake Eat Snake The Nation, posted 1 July 1999 (19 July 1999 issue). Accessed 9 February 2006.

- ^ Kahan, Barak & Efrat 1983, p. 36.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Shahid, Leila (Autumn 2002). "The Sabra and Shatila Massacres: Eye-Witness Reports". Journal of Palestine Studies. 32 (1): 36–58. doi:10.1525/jps.2002.32.1.36. ISSN 0377-919X.

- ^ Kahan, Barak & Efrat 1983, pp. 11, 31.

- ^ a b c d Panorama: "The Accused", broadcast by the BBC, 17 June 2001; transcript Archived 23 June 2024 at the Wayback Machine accessed 9 February 2006.

- ^ Mark Ensalaco, Middle Eastern Terrorism: From Black September to 11 September Archived 8 October 2024 at the Wayback Machine, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012 p. 137.

- ^ Traboulsi 2007.

- ^ a b Kahan, Barak & Efrat 1983, p. 9.

- ^ Kahan, Barak & Efrat 1983, p. 11.

- ^ Kahan, Barak & Efrat 1983, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Malone, Linda (14 June 2001). "Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, A War Criminal". The Jerusalem Fund / The Palestine Center. Information Brief. Archived from the original on 14 July 2006. Retrieved 24 February 2006.

- ^ Fisk, Robert (13 February 2007). The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East. National Geographic Books. pp. 484, 488–489. ISBN 978-1-4000-7517-1.

- ^ Becker 1984, pp. 239, 356–357.

- ^ Becker 1984, p. 264.

- ^ a b Kahan, Barak & Efrat 1983, p. 13.

- ^ Byman, Daniel (2011). A High Price: The Triumphs and Failures of Israeli Counterterrorism. Oxford University Press, US. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-19-983045-9.

- ^ Friedman, Thomas L. (2010). From Beirut to Jerusalem. Macmillan. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-374-70699-9. Archived from the original on 8 October 2024. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ^ Friedman, Thomas L. (26 September 1982). "The Beirut Massacre: The Four Days". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 October 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b Hatem, Robert Maroun. "7: The Massacres at Sabra and Shatilla". From Israel to Damascus. Archived from the original on 12 May 2004. Retrieved 24 February 2006.

- ^ Hirst 2010, p. 156.

- ^ The New York Times, 26 September 1982. in Claremont Research p. 76

- ^ Kahan, Barak & Efrat 1983, p. 14.

- ^ a b Kahan, Barak & Efrat 1983, p. 12.

- ^ Kahan, Barak & Efrat 1983, p. 23.

- ^ Morris, Benny (2 March 2018). "The Israeli Army Papers That Show What Ariel Sharon Hid From the Cabinet in the First Lebanon War". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 2 December 2023.

- ^ Kahan, Barak & Efrat 1983, p. 16.

- ^ Kahan, Barak & Efrat 1983, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Kahan, Barak & Efrat 1983, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Kahan, Barak & Efrat 1983.

- ^ Kahan, Barak & Efrat 1983, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Kahan, Barak & Efrat 1983, p. 19.

- ^ Aftenposten Middle East correspondent Harbo was also quoted with the same information on ABC News "Close up, Beirut Massacres", broadcast 7 January 1983.

- ^ "Syrians aid 'Butcher of Beirut' to hide from justice". The Daily Telegraph. 17 June 2001. Archived from the original on 14 April 2024.

- ^ Lamb, Franklin. "Remembering Janet Lee Stevens, martyr for the Palestinian refugees". Archived from the original on 3 April 2011.

- ^ Kamm, Henry (17 September 1982). "Arafat Demands 3 Nations Return Peace Force to Beirut". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 October 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ a b Rmeileh, Rami (18 September 2023). "Sabra & Shatila echoes past & ongoing Palestinian suffering". The New Arab. Archived from the original on 6 June 2024. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ Agencies, The New Arab Staff & (6 February 2021). "Lokman Slim: The daring Lebanese activist, admired intellectual". The New Arab. Archived from the original on 6 June 2024. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

Their film "Massaker" — which studied six perpetrators of the 1982 Christian militia massacres of 1,000 people at the Sabra and Shatila Palestinian camps in Beirut — was awarded the Fipresci Prize at the 2005 Berlinale.

- ^ Schiff & Ya'ari 1985, p. 282.

- ^ Nuwayhed al-Hout 2004, p. 296.

- ^ Fisk, Robert (15 September 2002). "The forgotten massacre". The Independent. Archived from the original on 8 June 2024.

- ^ Kapeliouk, Amnon (1982). Enquête sur un massacre: Sabra et Chatila [Investigation into a massacre: Sabra and Shatila] (in French). Translated by Jehshan, Khalil. Seuil. ISBN 2-02-006391-3. Archived from the original on 7 February 2006. Retrieved 15 July 2005.

- ^ Campagna, Joel (April 2002). "The Usual Suspects". World Press Review. 49 (4). Archived from the original on 2 July 2024. Retrieved 24 February 2006.

- ^ Menargues 2004, pp. 469–470.

- ^ Traboulsi 2007, p. 218: "On Wednesday 15th, units of the elite Israeli army 'reconnaissance' force, the Sayeret Mat`kal, which had already carried out the assassination of the three PLO leaders in Beirut, entered the camps with a mission to liquidate a selected number of Palestinian cadres. The next day, two units of killers were introduced into the camps, troops from Sa'd Haddad's Army of South Lebanon, attached to the Israeli forces in Beirut, and the LF security units of Elie Hobeika known as the Apaches, led by Marun Mash'alani, Michel Zuwayn and Georges Melko"

- ^ Avon, Dominique; Khatchadourian, Anaïs-Trissa; Todd, Jane Marie (2012). Hezbollah: A History of the "Party of God". Harvard University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-674-07031-8.

That triggered the massacre of Palestinians in Sabra and Shatila camps in three waves, according to Alain Menargues, first at the hands of special Israeli units, whose troops reoccupied West Beirut; then by the groups in the SLA; and finally by men from the Jihaz al-Amn, a Lebanese forces special group led by Elie Hobeika.

- ^ a b c Traboulsi 2007, p. 219.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (1999). The Fateful Triangle: The United States, Israel, and the Palestinians. Pluto Press. p. 377. ISBN 978-0-7453-1530-0.

- ^ Shultz, George P. (2010). Turmoil and Triumph: Diplomacy, Power, and the Victory of the American Deal. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-2311-6.

- ^ U.N. General Assembly, Resolution 37/123, adopted between 16 and 20 December 1982. Archived 29 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ^ "Voting Summary U.N. General Assembly Resolution 37/123D". Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ^ Kuper, Leo (1997). "Theoretical Issues Relating to Genocide: Uses and Abuses". In Andreopoulos, George J. (ed.). Genocide: Conceptual and Historical Dimensions. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 37. ISBN 0-8122-1616-4.

- ^ Schabas 2000, p. 455.

- ^ a b c Schabas 2000, p. 541.

- ^ Schabas 2000, p. 541-542.

- ^ Schabas 2000, p. 540.

- ^ Schabas 2000, p. 542.

- ^ "Professor William A. Schabas". Irish Centre for Human Rights at the National University of Ireland. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007.

- ^ Schabas 2000, p. 235.

- ^ Hirst 2010.

- ^ a b c Kahan, Barak & Efrat 1983, p. 49.

- ^ Tolworthy, Chris (March 2002). "Sabra and Shatila massacres – why do we ignore them?". September 11th and Terrorism FAQ. Global Issues. Archived from the original on 26 February 2024. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ Llewellyn, Tim (20 April 1998). "Israel and the PLO". BBC News. BBC. Archived from the original on 22 June 2024. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ^ "Around the world; Israeli General Resigns From Army". The New York Times. 15 August 1983. Archived from the original on 12 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Israelis Protest Sabra and Shatila Massacre" Archived 8 October 2024 at the Wayback Machine, Center for Israel Education, 25 September 1982, accessed 8 September 2024.

- ^ Tamara Zieve (23 September 2012). "This Week In History: Masses protest Sabra, Shatila". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 6 December 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- ^ Lehmann, Noam; Schejter, Iddo; Kirsch, Elana (8 September 2024). "Organizers claim largest-ever rally in Tel Aviv as calls for hostage deal intensify. Groups behind demonstrations estimate 500,000 at main protest, 250,000 at other rallies around country". Times of Israel. Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- ^ Hirst 2010, p. 168.

- ^ Haugbolle, Sune (2010). War and Memory in Lebanon. Cambridge University Press. pp. 144–145. ISBN 978-0-521-19902-5. Archived from the original on 8 October 2024. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ^ "Time Collection: Ariel Sharon". Time. Archived from the original on 16 January 2006. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ Kroeger, Brooke W. (25 January 1985). "Sharon Loses Libel Suit; Time Cleared of Malice". Archived from the original on 3 March 2024. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ Flint, Julie (25 November 2001). "Vanished victims of Israelis return to accuse Sharon". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 October 2023. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

The fate of the disappeared of Sabra and Chatila will come back to haunt Sharon when a Belgian court hears a suit brought by their relatives alleging his involvement in the massacres.

- ^ Universal Jurisdiction Update, December 2003 Archived 10 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Redress (London). Retrieved 5 January 2010; section Belgium, subsection 'Shabra and Shatila'.

- ^ Penney, J. (2012). Structures of Love, The: Art and Politics beyond the Transference. State University of New York Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-1438439747. Archived from the original on 8 October 2024. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

Works cited

- Alpher, Yossi (2015). Periphery: Israel's Search for Middle East Allies. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-3102-3. Archived from the original on 11 March 2024. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- Becker, Jillian (1984). PLO: The Rise and Fall of the Palestine Liberation Organization. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4918-4435-9.

- Fisk, Robert (2001). Pity the Nation: Lebanon at War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280130-2.

- Gonzalez, Nathan (2013). The Sunni-Shia Conflict: Understanding Sectarian Violence in the Middle East. Nortia Media Ltd. ISBN 978-0-9842252-1-7.

- Hirst, David (2010). Beware of small states: Lebanon, battleground of the Middle East. Nation Books. ISBN 978-0-571-23741-8.

- Kahan, Yitzhak; Barak, Aharon; Efrat, Yona (1983). The Commission of Inquiry into events at the refugee camps in Beirut 1983 Final Report (Authorized translation) (Report). JSTOR 20692582.

- MacBride, Seán; Asmal, A. K.; Bercusson, B.; Falk, R. A.; Pradelle, G. de la; Wild, S. (1983). Israel in Lebanon: The Report of International Commission to enquire into reported violations of International Law by Israel during its invasion of the Lebanon. London: Ithaca Press. ISBN 0-903729-96-2.

- Menargues, Alain (2004). Secrets de la Guerre du Liban [Secrets of the Lebanese War] (in French).

- Nuwayhed al-Hout, Bayan (2004). Sabra and Shatila September 1982. Pluto Press. ISBN 0-7453-2303-0. Archived from the original on 8 October 2024. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- Quandt, William B. (1993). Peace Process: American Diplomacy and the Arab-Israeli Conflict Since 1967. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22374-5. Archived from the original on 8 October 2024. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- Schabas, William (2000). Genocide in International Law: The Crime of Crimes. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521782627.

- Schiff, Ze'ev; Ya'ari, Ehud (1985). Israel's Lebanon War. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-60216-1.

- Traboulsi, Fawwaz (2007). A History of Modern Lebanon. Pluto Press. ISBN 9780745324371.

Bibliography

- Hamdan, Ajal (16 September 2003). "Remembering Sabra and Shatila". Aljazeera. Archived from the original on 25 December 2005. Retrieved 4 December 2004.

- Klein, A. J. (2005). Striking Back: The 1972 Munich Olympics Massacre and Israel's Deadly Response. New York: Random House. ISBN 1-920769-80-3.

- Lewis, Bernard (Winter 2006). "The New Anti-Semitism". The American Scholar. 75 (1): 25–36. Archived from the original on 8 September 2011.. The paper is based on a lecture delivered at Brandeis University on 24 March 2004.

- Lewis, Bernard (1999). Semites and Anti-Semites: An Inquiry into Conflict and Prejudice. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-31839-7.

- Morris, Benny; Black, Ian (1991). Israel's Secret Wars: A History of Israel's Intelligence Services. Grove. ISBN 0-8021-1159-9.

- "New 'evidence' in Sharon trial". BBC News. 8 May 2002. Retrieved 4 December 2004.

- Shashaa, Esam (no date).

- United Nations General Assembly, A/RES/37/123(A-F). The situation in the Middle East (16 December 1982). A/RES/37/123(A-F) of 16 December 1982

- White, Matthew. "Secondary Wars and Atrocities of the Twentieth Century". Retrieved 4 December 2004.

- Harris, William (1996). Faces of Lebanon: Sects, Wars, and Global Extensions. Princeton, USA: Markus Wiener Publishers. ISBN 1-55876-115-2.

Notes

Further reading

- Bregman, Ahron (2002). Israel's Wars: A History Since 1947. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-28716-2.

- "1982: Refugees massacred in Beirut camps". BBC On This Day. BBC. 17 September 1982. Retrieved 17 June 2022. * BBC News archive and video

- "Sabra Shatila Massacre Photos". littleredbutton.com. 9 October 2004. Archived from the original on 9 October 2004. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Tamal, Ahmad (no date). Sabra and Shatila. All About Palestine. Retrieved 4 December 2004.

- "Eyewitness Lebanon". littleredbutton.com. 9 October 2004. Archived from the original on 9 October 2004. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Chomsky, Noam (1989). Necessary Illusions: Thought control in democratic societies. South End Press. ISBN 0-89608-366-7. Archived from the original on 7 June 2000.

- Anziska, Seth (26 April 2021). "Sabra and Shatila: New Revelations". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- Fisk, Robert. "Sabra and Shatila". Countercurrents. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- Fisk, Robert (28 November 2001). "Another war on terror. Another proxy army. Another mysterious". The Independent. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- Mason, Barnaby (17 April 2002). "Analysis: 'War crimes' on West Bank". BBC News. Retrieved 4 December 2004.

- Sabra and Shatila, the unforgivable slaughter Archived 6 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine (in French)

- The Kahan Commission on Sabra and Shatila Massacre, published by Israel State Archives

- Sabra and Shatila massacre

- Anti-Palestinian sentiment in Lebanon

- Massacres of the Lebanese Civil War

- Mass murder in Beirut

- Beirut in the Lebanese Civil War

- Persecution of Muslims by Christians

- September 1982 events in Asia

- Christian terrorism in Asia

- 1982 murders in Lebanon

- Violence against Shia Muslims in Lebanon

- Massacres of Shia Muslims

- Massacres of Palestinians

- 1980s crimes in Beirut

- Israeli war crimes in Lebanon

- Genocides in Asia

- Wartime sexual violence in Asia