Belt and Road Initiative

Belt and Road Initiative and related projects | |

| Abbreviation | BRI |

|---|---|

| Formation | 2013 2017 (Forum) 2019 (Forum) 2023 (Forum) |

| Founder | |

| Legal status | Active |

| Purpose | Promote economic development and inter-regional connectivity |

| Location |

|

| Website | www |

| The Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-century Maritime Silk Road | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 丝绸之路经济带和21世纪海上丝绸之路 | ||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 絲綢之路經濟帶和21世紀海上絲綢之路 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| One Belt, One Road (OBOR) | |||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 一带一路 | ||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 一帶一路 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

|

|---|

|

|

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI or B&R[1]), known in China as the One Belt One Road[a] and sometimes referred to as the New Silk Road,[2] is a global infrastructure development strategy adopted by the Chinese government in 2013 to invest in more than 150 countries and international organizations.[3] The BRI is composed of six urban development land corridors linked by road, rail, energy, and digital infrastructure and the Maritime Silk Road linked by the development of ports.

Chinese Communist Party (CCP) general secretary Xi Jinping originally announced the strategy as the "Silk Road Economic Belt" during an official visit to Kazakhstan in September 2013. "Belt" refers to the proposed overland routes for road and rail transportation through landlocked Central Asia along the famed historical trade routes of the Western Regions; "road" is short for the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, which refers to the Indo-Pacific sea routes through Southeast Asia to South Asia, the Middle East and Africa.[4]

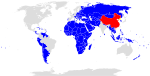

It is considered a centerpiece of Xi Jinping's foreign policy.[5] The BRI forms a central component of Xi's "Major Country Diplomacy"[b] strategy, which calls for China to assume a greater leadership role in global affairs in accordance with its rising power and status.[6] As of early 2024, more than 140 countries were part of the BRI.[7]: 20 The participating countries include almost 75% of the world's population and account for more than half of the world's GDP.[8]: 192

The initiative was incorporated into the constitution of the Chinese Communist Party in 2017.[5] The Xi Jinping Administration describes the initiative as "a bid to enhance regional connectivity and embrace a brighter future."[9] The project has a target completion date of 2049,[10] which will coincide with the centennial of the People's Republic of China (PRC)'s founding.

Numerous studies conducted by the World Bank have estimated that BRI can boost trade flows in 155 participating countries by 4.1 percent, as well as cutting the cost of global trade by 1.1 percent to 2.2 percent, and grow the GDP of East Asian and Pacific developing countries by an average of 2.6 to 3.9 percent.[11][12] According to London-based consultants Centre for Economics and Business Research, BRI is likely to increase the world GDP by $7.1 trillion per annum by 2040, and that benefits will be "widespread" as improved infrastructure reduces "frictions that hold back world trade". CEBR also concludes that the project will be likely to attract further countries to join, if the global infrastructure initiative progresses and gains momentum.[13][14][15]

Supporters praise the BRI for its potential to boost the global GDP, particularly in developing countries. However, there has also been criticism over human rights violations and environmental impact, as well as concerns of debt-trap diplomacy resulting in neocolonialism and economic imperialism. These differing perspectives are the subject of active debate.[16]

Objectives

[edit]Background

[edit]China's policy of channeling its construction companies abroad began with Jiang Zemin's Go Out policy.[17]: 67 Xi Jinping's BRI built on and expanded this policy[17]: 67 as well as built on Jiang's China Western Development policy.[18]: 149

Xi announced the BRI concept as the "Silk Road Economic Belt" on 7 September 2013 at Nazarbayev University in Astana, Kazakhstan [17]: 75 In October 2013 during a speech delivered in Indonesia, Xi stated that China planned to build a "twenty-first century Maritime Silk Road" to enhance cooperation in Southeast Asia and beyond.[17]: 75

The BRI's stated objectives are "to construct a unified large market and make full use of both international and domestic markets, through cultural exchange and integration, to enhance mutual understanding and trust of member nations, resulting in an innovative pattern of capital inflows, talent pools, and technology databases."[19] The Belt and Road Initiative addresses an "infrastructure gap" and thus has the potential to accelerate economic growth across the Asia Pacific, Africa and Central and Eastern Europe. A report from the World Pensions Council estimates that Asia, excluding China, requires up to US$900 billion of infrastructure investments per year over the next decade, mostly in debt instruments, 50% above current infrastructure spending rates.[20] The gaping need for long-term capital explains why many Asian and Eastern European heads of state "gladly expressed their interest in joining this new international financial institution focusing solely on 'real assets' and infrastructure-driven economic growth".[21]

The initial focus has been infrastructure investment, education, construction materials, railway and highway, automobile, real estate, power grid, and iron and steel.[22] Already, some estimates list the Belt and Road Initiative as one of the largest infrastructure and investment projects in history, covering more than 68 countries, including 65% of the world's population and 40% of the global gross domestic product as of 2017.[23][24] The project builds on the old trade routes that once connected China to the west, Marco Polo and Ibn Battuta's routes in the north and the maritime expedition routes of Ming dynasty admiral Zheng He in the south. The Belt and Road Initiative now refers to the entire geographical area of the historic "Silk Road" trade route, which has been continuously used in antiquity.[25]

The goals of the BRI were officially presented for the first time in a 2015 document, the Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Belt and Road.[17]: 76 It outlined six economic corridors for trade and investment connectivity would be implemented.[17]: 76

The BRI develops new markets for Chinese firms, channels excess industrial capacity overseas, increases China's access to resources, and strengthens its ties with partner countries.[17]: 34 The initiative generates its own export demand because Chinese loans enable participating countries to develop infrastructure projects involving Chinese firms and expertise.[7]: 43 The infrastructure developed also helps China to address the imbalance between its more developed eastern regions and its less developed western regions.[7]: 43

For developing countries, the BRI is appealing because of the opportunities it offers to alleviate their economic disadvantages relative to Western countries.[17]: 49 The BRI offers them infrastructure development, financial assistance, and technical assistance from China.[26]: 223 The increase in foreign direct investment and increased trade linkages also increases employment and poverty alleviation for these countries.[26]: 224

While some countries, especially the United States, view the project critically because of possible Chinese government influence, others point to the creation of a new global growth engine by connecting and moving Asia, Europe and Africa closer together.[27]

In the maritime silk road, which is already the route for more than half of all containers in the world, deep-water ports are being expanded, logistical hubs are being built, and new traffic routes are being created in the hinterland. The maritime silk road runs with its connections from the Chinese coast to the south, linking Hanoi, Kuala Lumpur, Singapore, and Jakarta, then westward linking the Sri Lankan capital city of Colombo, and Malé, capital of the Maldives, and onward to East Africa, and the city of Mombasa, in Kenya. From there the linkage moves northward to Djibouti, through the Red Sea and the Suez Canal to the Mediterranean, thereby linking Haifa, Istanbul, and Athens, to the Upper Adriatic region to the northern Italian hub of Trieste, with its international free port and its rail connections to Central Europe and the North Sea.[28][29][30][31]

As a result, Poland, the Baltic States, Northern Europe, and Central Europe are also connected to the maritime silk road and logistically linked to East Africa, India and China via the Adriatic ports and Piraeus. All in all, the ship connections for container transports between Asia and Europe will be reorganized. In contrast to the longer East Asian traffic via north-west Europe, the southern sea route through the Suez Canal towards the junction Trieste shortens the goods transport by at least four days.[32][33][34]

In connection with the Silk Road project, China is also trying to network worldwide research activities.[35]

Simon Shen and Wilson Chan have compared the initiative to the post-World War II Marshall Plan.[36] It is the largest infrastructure investment by a great power since the Marshall Plan.[7]: 1

China intentionally frames the BRI flexibly in order to adapt it to changing needs or policies, such as the addition of a "Health Silk Road" during the COVID-19.[17]: 147 The Health Silk Road (HSR) is an initiative under China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) aimed at enhancing public health infrastructure and fostering international cooperation in healthcare. Initiated as part of China's broader strategy to engage in global health governance, the HSR seeks to improve healthcare facilities, enhance disease prevention, and strengthen healthcare cooperation across participating countries. The initiative includes the construction of healthcare facilities, such as hospitals in Pakistan and Laos, and collaborative programs with global organizations like the World Health Organization. Academic Shaoyu Yuan finds that while the HSR contributes to health sector improvements in participating nations, it also prompts discussions regarding the long-term debt sustainability and the transparency of project execution. As the HSR expands, it exemplifies China's role in global health diplomacy, reflecting a complex interplay between development goals and geopolitical strategy.[37]

Initiative name

[edit]

The official name for the initiative is the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road Development Strategy (丝绸之路经济带和21世纪海上丝绸之路发展战略),[38] which was initially abbreviated as the One Belt One Road (Chinese: 一带一路) or the OBOR strategy. The English translation has been changed to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) since 2016, when the Chinese government considered the emphasis on the words "one" and "strategy" were prone to misinterpretation and suspicion, so they opted for the more inclusive term "initiative" in its translation.[39][40] However, "One Belt One Road" is still the reference term in Chinese-language media.[41]

International relations

[edit]The Belt and Road Initiative is believed by some analysts to be a way to extend Chinese economic and political influence.[24][42] Some geopolitical analysts have couched the Belt and Road Initiative in the context of Halford Mackinder's heartland theory.[43][44][45] Scholars have noted that official PRC media attempts to mask any strategic dimensions of the Belt and Road Initiative as a motivation,[46] while others note that the BRI also serves as signposts for Chinese provinces and ministries, guiding their policies and actions.[47] Academic Keyu Jin writes that while the BRI does advance strategic interests for China, it also reflects the CCP's vision of a world order based on "building a global community of shared future".[48]: 281–282

China has already invested billions of dollars in several South Asian countries like Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Afghanistan to improve their basic infrastructure, with implications for China's trade regime as well as its military influence. This project can also become a new economic corridor for different regions. For example, in the Caucasus region, China considered cooperation with Armenia from May 2019. Chinese and Armenian sides had multiple meetings, signed contracts, initiated a north–south road program to solve even infrastructure-related aspects.[49]

Military implications

[edit]The BRI has been viewed as part of a strategy to lessen the effect of choke points such as the Strait of Malacca in the event of a military conflict and to blunt the U.S. island chain strategy.[50][51][52][53] A 2023 study by AidData of the College of William & Mary determined that overseas port locations subject to significant BRI investment raise questions of dual military and civilian use and may be favorable for future naval bases.[54][55]

Writing in 2023, David H. Shinn and academic Joshua Eisenman state that through the BRI, China seeks to strengthen its position and diminish American military influence, but that China's BRI activity is likely not a prelude to American-style military bases or American-style global military presence.[56]: 161

Other analysts characterize China's construction of ports which could have dual-uses as an attempt to avoid the necessity of establishing strictly military bases.[56]: 273 According to academic Xue Guifang, China is not motivated to repeat the model of the People's Liberation Army Support Base in Djibouti.[56]: 273

Western regions

[edit]Economic development of China's less developed western regions, particularly Xinjiang, is one of the government's stated goals in pursuing the BRI.[57][58]: 199 The strategic location of Xinjiang has also been recognized as central. In 2014, state media outlet Xinhua News Agency stated Xinjiang "connects Pakistan, Mongolia, Russia, India, and four other central Asian countries with a borderline extending 5,600 km, giving it easy access to the Eurasian heartland."[59] Some analysts have suggested that the CCP considers Xinjiang's local population, the Uyghurs, and their attachment to their traditional lands potential threats to the BRI's success, or it fears that developing Xinjiang may also open it up to radicalizing Islamic influences from other states which are participating in the BRI.[60][61][62][63]

Leadership

[edit]A leading group was formed sometime in late 2014, and its leadership line-up publicized on 1 February 2015. This steering committee reports directly into the State Council of China and is composed of several political heavyweights, evidence of the importance of the program to the government. Then Vice-Premier Zhang Gaoli, who was also a member of the 7-man CCP Politburo Standing Committee, was named leader of the group, and Wang Huning, Wang Yang, Yang Jing, and Yang Jiechi named deputy leaders.[64]

On 28 March 2015, China's State Council outlined the principles, framework, key areas of cooperation and cooperation mechanisms with regard to the initiative.[65] The BRI is considered a central element within China's foreign policy, and was incorporated into the CCP's constitution in 2017 during its 19th Congress.[66][56]: 58 The BRI represents a set of policies for Chinese engagement with the global South, including diversifying resource and energy supplies, building loan-funded infrastructure using Chinese companies, creating new markets for Chinese companies, and engaging global South countries simultaneously at bilateral and regional levels.[17]: 6

With regard to China and the African countries, the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) is a significant multi-lateral cooperation mechanism for facilitating BRI projects.[67] The China-Arab States Cooperation Forum (CASCF) serves a similar coordinating role with regard to BRI projects in the Arab states.[67]

Membership

[edit]This section's factual accuracy may be compromised due to out-of-date information. (July 2024) |

Countries join the Belt and Road Initiative by signing a memorandum of understanding with China regarding their participation in it. The Government of China maintains a listing of all involved countries on its Belt and Road Portal,[68] and state media outlet Xinhua News Agency puts out a press release whenever a memorandum of understanding related to the Belt and Road Initiative is signed with a new country.[69] Not counting China, there were 154 countries formally affiliated with the Belt and Road Initiative As of August 2023[update] according to observers at Fudan University's Green Finance and Development Center,[70] and an independent analysis from Germany from the same time also found 148 member states out of 249 political entities surveyed.[71] The Council on Foreign Relations additionally found 139 member countries as of March 2021;[72] countries that are documented as joining since then include Syria[73] and Argentina.[74] The full list of current members according to the Chinese government[68] is below:

Current members

[edit] Afghanistan[75]

Afghanistan[75] Albania[75]

Albania[75] Algeria[75]

Algeria[75] Angola[75]

Angola[75] Antigua and Barbuda[75]

Antigua and Barbuda[75] Armenia[75]

Armenia[75] Austria[75]

Austria[75] Azerbaijan[75]

Azerbaijan[75] Bahrain[75]

Bahrain[75] Bangladesh[75]

Bangladesh[75] Barbados[75]

Barbados[75] Belarus[75]

Belarus[75] Benin[75]

Benin[75] Bolivia[75]

Bolivia[75] Bosnia and Herzegovina[75]

Bosnia and Herzegovina[75] Botswana[75]

Botswana[75] Brunei[75]

Brunei[75] Bulgaria[75]

Bulgaria[75] Burkina Faso[76]

Burkina Faso[76] Burundi[75]

Burundi[75] Cambodia[75]

Cambodia[75] Cape Verde[75]

Cape Verde[75] Cameroon[75]

Cameroon[75] Central African Republic[75]

Central African Republic[75] Chad[75]

Chad[75] Chile[75]

Chile[75] China[75]

China[75] Comoros[75]

Comoros[75] Democratic Republic of the Congo[75]

Democratic Republic of the Congo[75] Republic of Congo[75]

Republic of Congo[75] Cook Islands[75]

Cook Islands[75] Costa Rica[75]

Costa Rica[75] Croatia[75]

Croatia[75] Cuba[75]

Cuba[75] Cyprus[75]

Cyprus[75] Czech Republic[75]

Czech Republic[75] Djibouti[75]

Djibouti[75] Dominica[75]

Dominica[75] Dominican Republic[75]

Dominican Republic[75] Ecuador[75]

Ecuador[75] Egypt[75]

Egypt[75] El Salvador[75]

El Salvador[75] Equatorial Guinea[75]

Equatorial Guinea[75] Eritrea[75]

Eritrea[75] Ethiopia[75]

Ethiopia[75] Fiji[75]

Fiji[75] Gabon[75]

Gabon[75] Gambia[75]

Gambia[75] Georgia[75]

Georgia[75] Ghana[75]

Ghana[75] Greece[75]

Greece[75] Grenada[75]

Grenada[75] Guinea[75]

Guinea[75] Guinea-Bissau[75]

Guinea-Bissau[75] Guyana[75]

Guyana[75] Honduras[77]

Honduras[77] Hungary[75]

Hungary[75] Indonesia[75]

Indonesia[75] Iran[75]

Iran[75] Iraq[75]

Iraq[75] Ivory Coast[75]

Ivory Coast[75] Jamaica[75]

Jamaica[75] Jordan[78]

Jordan[78] Kazakhstan[75]

Kazakhstan[75] Kenya[75]

Kenya[75] Kiribati[75]

Kiribati[75] Kuwait[75]

Kuwait[75] Kyrgyzstan[75]

Kyrgyzstan[75] Laos[75]

Laos[75] Latvia[75]

Latvia[75] Lebanon[75]

Lebanon[75] Lesotho[75]

Lesotho[75] Liberia[75]

Liberia[75] Libya[75]

Libya[75] Lithuania[75]

Lithuania[75] Luxembourg[75]

Luxembourg[75] Madagascar[75]

Madagascar[75] Malawi[75]

Malawi[75] Malaysia[75]

Malaysia[75] Maldives[75]

Maldives[75] Mali[75]

Mali[75] Malta[75]

Malta[75] Mauritania[75]

Mauritania[75] Mauritius[79]

Mauritius[79] Micronesia[75]

Micronesia[75] Moldova[75]

Moldova[75] Mongolia[75]

Mongolia[75] Montenegro[75]

Montenegro[75] Morocco[75]

Morocco[75] Mozambique[75]

Mozambique[75] Myanmar[75]

Myanmar[75] Namibia[75]

Namibia[75] Nepal[75]

Nepal[75] New Zealand[75]

New Zealand[75] Nicaragua[75]

Nicaragua[75] Niger[75]

Niger[75] Nigeria[75]

Nigeria[75] Niue[75]

Niue[75] North Macedonia[75]

North Macedonia[75] Oman[75]

Oman[75] Pakistan[75]

Pakistan[75] Palestine[75]

Palestine[75] Panama[75]

Panama[75] Papua New Guinea[75]

Papua New Guinea[75] Peru[75]

Peru[75] Poland[75]

Poland[75] Portugal[75]

Portugal[75] Qatar[75]

Qatar[75] Romania[75]

Romania[75] Russia[75]

Russia[75] Rwanda[79]

Rwanda[79] Samoa[75]

Samoa[75] São Tomé and Príncipe[80]

São Tomé and Príncipe[80] Saudi Arabia[75]

Saudi Arabia[75] Senegal[79]

Senegal[79] Serbia[75]

Serbia[75] Seychelles[75]

Seychelles[75] Sierra Leone[75]

Sierra Leone[75] Singapore[75]

Singapore[75] Slovakia[75]

Slovakia[75] Slovenia[75]

Slovenia[75] Solomon Islands[75]

Solomon Islands[75] Somalia[75]

Somalia[75] South Africa[75]

South Africa[75] South Sudan[75]

South Sudan[75] Sri Lanka[75]

Sri Lanka[75] Sudan[75]

Sudan[75] Suriname[75]

Suriname[75] Syria[75]

Syria[75] Tajikistan[75]

Tajikistan[75] Tanzania[75]

Tanzania[75] Thailand[75]

Thailand[75] Timor-Leste[75]

Timor-Leste[75] Togo[75]

Togo[75] Tonga[75]

Tonga[75] Trinidad and Tobago[75]

Trinidad and Tobago[75] Tunisia[75]

Tunisia[75] Turkey[75]

Turkey[75] Turkmenistan[75]

Turkmenistan[75] Uganda[75]

Uganda[75] United Arab Emirates[75]

United Arab Emirates[75] Uruguay[75]

Uruguay[75] Uzbekistan[75]

Uzbekistan[75] Vanuatu[75]

Vanuatu[75] Venezuela[75]

Venezuela[75] Vietnam[75]

Vietnam[75] Yemen[75]

Yemen[75] Zambia[75]

Zambia[75] Zimbabwe[75]

Zimbabwe[75]

Past members

[edit]Financing

[edit]China's investment in the BRI began at a moderate level in 2013 and increased significantly over 2014 and 2015.[84]: 214 Investment volume peaked in 2016 and 2017.[84]: 214 Afterwards, investments decreased gradually, and then significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic.[84]: 214 The BRI's lowest investment volume was in 2023.[84]: 214

China's investment in the Maritime Silk Road portion of the BRI has grown at a steady pace.[84]: 214 As of 2023, Maritime Silk Road investments were 60% of the BRI's total investment volume.[84]: 214

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB)

[edit] Prospective members (regional)

Members (regional)

Prospective members (non-regional)

Members (non-regional) |

The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, first proposed in October 2013, is a development bank dedicated to lending for infrastructure projects. As of 2015, China announced that over one trillion yuan (US$160 billion) of infrastructure-related projects were in planning or construction.[85]

The primary goals of AIIB are to address the expanding infrastructure needs across Asia, enhance regional integration, promote economic development and improve public access to social services.[86] At inception, the AIIB was explicitly linked to the BRI.[7]: 166 The AIIB was subsequently broadened to include investments with states that are not involved with the BRI.[7]: 166

Loans through AIIB are accessible on AIIB's website, unlike many other forms of Chinese investment through the BRI.[17]: 85

Silk Road Fund

[edit]On 29 December 2014, China established the Silk Road Fund with total capital of US$40 billion and ¥100 billion.[26]: 221 The Silk Road Fund invests in BRI infrastructure, resource development, energy development, industrial cooperation, and financial cooperation.[26]: 221 The Karot Hydropower Project in Pakistan was its first project.[26]: 221–222

China Investment Corporation

[edit]China Investment Corporation supports the BRI by investing in its infrastructure projects, participating in other BRI-related development funds, and assisting Chinese corporations with foreign mergers and acquisitions.[87]: 124 China Investment Corporation also invested in the Silk Road Fund.[26]: 221

CIC's domestic subsidiary Central Huijin indirectly supports the BRI through its support of domestic financial institutions, such as policy banks or state-owned commercial banks, which in turn fund BRI projects.[87]: 124

Policy banks

[edit]Policy banks, including the Chinese Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China, have important roles in funding BRI projects.[7]: 167

Other financing

[edit]Between 2015 and 2020, the Bank of China lent over US$185.1 billion for BRI projects.[88]: 143

As of April 2019, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China had lent over US$100 billion for BRI projects.[88]: 143

Debt sustainability

[edit]In 2017, China joined the G20 Operational Guidelines for Sustainable Financing and in 2019 to the G20 Principles for Quality Infrastructure Investment. The Center for Global Development described China's New Debt Sustainability Framework as "virtually identical" to the World Bank's and IMF's own debt sustainability framework.[89][90] According to academic Jeremy Garlick, for many impoverished countries, China is the best available option for development finance and practical assistance.[17]: 6 Western investors and the World Bank have been reluctant to invest in troubled countries like Pakistan, Cambodia, Tajikistan, and Montenegro, which China is willing to invest in through the BRI.[17]: 146–147 Generally, the United States and EU have not offered global South countries with investment comparable to what China offers through the BRI.[17]: 147

China is the largest bilateral lender in the world.[91] Loans are backed by collateral such as rights to a mine, a port or money.[5]

This policy has been alleged by the U.S. Government to be a form of debt-trap diplomacy; however, the term itself has come under scrutiny as analysts and researchers have pointed out that there is no evidence to prove that China is deliberately aiming to do debt-trap diplomacy.[92] Research from Deborah Brautigam, an international political economy professor at Johns Hopkins University, and Meg Rithmire, an associate professor at Harvard Business School, have disputed the allegations of debt-trap diplomacy by China and pointed out that "Chinese banks are willing to restructure the terms of existing loans and have never actually seized an asset from any country, much less the port of Hambantota". In an editorial letter, they argued that it was 'long overdue' for people to know the truth and not to have it be "willfully misunderstood".[93] Writing in 2023, academic and former UK diplomat Kerry Brown states that China's relationship to the Hambantota port has become the opposite of the theorized debt-trap modus operandi.[94]: 56 Brown observes that China has had to commit more money to the project, expose itself to further risk, and has had to become entangled in complex local politics.[94]: 56 As of 2024, the port has not been a significant economic success, although shipping through the port is on the increase.[7]: 69

In his comparison of BRI loans to IMF loans and Paris Club loans, which have not been very successful in reducing the debt of developing countries, academic Jeremy Garlick concludes that there is no reason to believe the BRI framework is worse for developing countries' debt than Western lending frameworks.[17]: 69

For China itself, a report from Fitch Ratings doubts Chinese banks' ability to control risks, as they do not have a good record of allocating resources efficiently at home. This may lead to new asset quality problems for Chinese banks where most funding is likely to originate.[95]

It has been suggested by some scholars that critical discussions about an evolving BRI and its financing needs to transcend the debt-trap diplomacy debate. This concerns the networked nature of financial centers and the vital role of advanced business services (e.g. law and accounting) that bring agents and sites into view (such as law firms, financial regulators, and offshore centers) that are generally less visible in geopolitical analysis, but vital in the financing of BRI.[96]

In August 2022, China announced that it would forgive 23 of its interest-free loans to 17 African nations.[97] The loans had matured at the end of 2021.[97]

Effects

[edit]An analysis of BRI loans from 2007 to 2022 found that they make other forms of financing on the bond market more expensive for the debtor country.[98]

Infrastructure networks

[edit]The BRI is composed of six urban development land corridors linked by road, rail, energy, and digital infrastructure and the Maritime Silk Road linked by the development of ports.[7]: 1

The Silk Road has proven to be a productive but at the same time elusive concept, increasingly used as an evocative metaphor.[99] With China's 'Belt and Road Initiative', it has found fresh invocations and audiences.[100] These are the belts in the name, and there is also a maritime silk road.[101] Infrastructure corridors spanning some 60 countries, primarily in Asia and Europe but also including Oceania and East Africa, will cost an estimated US$4–8 trillion.[102][103] The land corridors include:[101]

- The China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) (Chinese:中国-巴基斯坦经济走廊; Urdu: پاكستان-چین اقتصادی راہداری) is the most developed land corridor of the BRI, as of at least 2024.[7]: 42 It is a US$62 billion collection of infrastructure projects throughout Pakistan[104][105][106] which aims to rapidly modernize Pakistan's transportation networks, energy infrastructure, and economy.[105][106][107][108] On 13 November 2016, CPEC became partly operational when Chinese cargo was transported overland to Gwadar Port for onward maritime shipment to Africa and West Asia.[109] CPEC and Gwadar port infrastructure is particularly significant because it opens routes independent of the Malacca strait.[110]: 99

- The New Eurasian Land Bridge, which runs from Western China to Western Russia through Kazakhstan, and includes the Silk Road Railway through China's Xinjiang Autonomous Region, Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, Poland and Germany. Astana, Kazakhstan is a major hub for the BRI, including related financial services and legal services.[7]: 45 Khorgos which straddles the Kazakhstan-China border, is the major dry port for this corridor and is the place where rail cargo switches from the standard gauge used in China to the wider gauge used in the former Soviet Union.[7]: 57

- The China–Mongolia–Russia Economic Corridor,[7]: 39 running from Northern China through Mongolia to the Russian Far East. The Russian government-established Russian Direct Investment Fund and China's China Investment Corporation, a Chinese sovereign wealth fund, partnered in 2012 to create the Russia-China Investment Fund, which concentrates on opportunities in bilateral integration.[111][112]

- The China–Central Asia–West Asia Corridor, which will run from Western China to Turkey.

- The China-Indochina Peninsula economic corridor, which will run from Southern China to Singapore.

- The Trans-Himalayan Multi-dimensional Connectivity Network, which will turn Nepal from a landlocked to a land-linked country.

This kind of connectivity is the focus of BRI efforts because China's significant economic growth has been supported by exports and the overland import of major quantities of raw materials and intermediate components.[110]: 98

By 2022, China had built cross-border highways and expressway networks to almost every nearby region.[110]: 99

Railway connectivity is a major focus of the BRI.[7]: 62 Use of BRI-related rail surged after the COVID-19 pandemic, which had congested air freight and sea shipping, and hampered port access.[110]: 99 As of 2024, multiple BRI railway projects were branded as the China Railways Express, which linked approximately 60 Chinese cities to approximately 50 European cities.[7]: 62

Silk Road Economic Belt

[edit]Xi Jinping visited Astana, Kazakhstan, and Southeast Asia in September and October 2013, and proposed jointly building a new economic area, the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) (Chinese: 丝绸之路经济带).[113] The "belt" includes countries on the original Silk Road through Central Asia, West Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. The initiative would create a cohesive economic area by building both hard infrastructure such as rail and road links and soft infrastructure such as trade agreements and a common commercial legal structure with a court system to police the agreements.[4]

Besides a zone largely analogous to the historical Silk Road, an expansion includes South Asia and Southeast Asia. The BRI is important from the Southeast Asian perspective because, with the exception of Singapore, Southeast Asian countries require significant infrastructure investment to advance their development.[114]: 210

Three belts are proposed. The North belt would go through Central Asia and Russia to Europe. The Central belt passes through Central Asia and West Asia to the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean. The South belt runs from China through Southeast Asia and South Asia and on to the Indian Ocean through Pakistan. The strategy will integrate China with Central Asia through Kazakhstan's Nurly Zhol infrastructure program.[115]

21st Century Maritime Silk Road

[edit]The "21st Century Maritime Silk Road" (Chinese:21世纪海上丝绸之路), or just the Maritime Silk Road, is the sea route 'corridor.'[4] It is a complementary initiative aimed at investing and fostering collaboration in Southeast Asia, Oceania and Africa through several contiguous bodies of water: the South China Sea, the South Pacific Ocean, and the wider Indian Ocean area.[116][117][118] It was first proposed in October 2013 by Xi Jinping in a speech to the Indonesian Parliament.[119]

The maritime Silk Road runs with its links from the Chinese coast to the south via Hanoi to Jakarta, Singapore and Kuala Lumpur through the Strait of Malacca via the Sri Lankan Colombo opposite the southern tip of India via Malé, the capital of the Maldives, to the East African Mombasa, from there to Djibouti, then through the Red Sea over the Suez Canal into the Mediterranean, there via Haifa, Istanbul and Athens to the Upper Adriatic to the northern Italian junction of Trieste with its international free port and its rail connections to Central Europe and the North Sea.[citation needed]

According to estimates in 2019, the land route of the Silk Road remains a niche project and the bulk of the Silk Road trade continues to be carried out by sea. The reasons are primarily due to the cost of container transport. The maritime Silk Road is also considered to be particularly attractive for trade because, in contrast to the land-based Silk Road leading through the sparsely populated Central Asia, there are on the one hand, far more states on the way to Europe and, on the other hand, their markets, development opportunities, and population numbers are far larger. In particular, there are many land-based links, such as the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Corridor (BCIM). Due to the attractiveness of this now subsidized sea route and the related investments, there have been major shifts in the logistics chains of the shipping sector in recent years.[120] Due to its unique geographical location, Myanmar is viewed to be playing a pivotal role in China's BRI projects.[121]

From the Chinese point of view, Africa is important as a market, raw material supplier and platform for the expansion of the new Silk Road – the coasts of Africa should be included. In Kenya's port of Mombasa, China has built a rail and road connection to the inland and to the capital Nairobi. To the northeast of Mombasa, a large port with 32 berths including an adjacent industrial area including infrastructure with new traffic corridors to South Sudan and Ethiopia is being built. A modern deep-water port, a satellite city, an airfield and an industrial area are being built in Bagamoyo, Tanzania. Further towards the Mediterranean, the Teda Egypt special economic zone is being built near the Egyptian coastal town of Ain Sochna as a joint Chinese-Egyptian project.[122][123]

-

Container ship transiting the Suez Canal

-

Mombasa Port on Kenya's Indian Ocean coast

As part of its Silk Road strategy, China is participating in large areas of Africa in the construction and operation of train routes, roads, airports and industry. In several countries, such as Zambia, Ethiopia and Ghana, dams have been built with Chinese help. In Nairobi, China is funding the construction of the tallest building in Africa, the Pinnacle Towers. With the Chinese investments of 60 billion dollars for Africa announced in September 2018, on the one hand, sales markets are created, and the local economy is promoted, and, on the other hand, African raw materials are made available for China.[124]

One of the Chinese bridgeheads in Europe is the port of Piraeus. Overall, Chinese companies are to invest a total of 350 million euros directly in the port facilities there by 2026 and a further 200 million euros in associated projects such as hotels.[125] In Europe, China wants to continue investing in Portugal with its deep-water port in Sines, but especially in Italy and there at the Adriatic logistics hub around Trieste. Venice, the historically important European endpoint of the maritime Silk Road, has less and less commercial importance today due to the shallow depth or silting of its port.[126]

The international free zone of Trieste provides in particular special areas for storage, handling and processing as well as transit zones for goods.[127][128] At the same time, logistics and shipping companies invest in their technology and locations in order to benefit from ongoing developments.[129][130] This also applies to the logistics connections between Turkey and the free port of Trieste, which are important for the Silk Road, and from there by train to Rotterdam and Zeebrugge. There is also direct cooperation, for example between Trieste, Bettembourg, and the Chinese province of Sichuan. While direct train connections from China to Europe, such as from Chengdu to Vienna overland, are partially stagnating or discontinued, there are (as of 2019) new weekly rail connections between Wolfurt or Nuremberg and Trieste or between Trieste, Vienna and Linz on the maritime Silk Road.[131][132]

There are also extensive intra-European infrastructure projects to adapt trade flows to current needs. Concrete projects (as well as their financing), which are to ensure the connection of the Mediterranean ports with the European hinterland, are decided among others at the annual China-Central-East-Europe summit, which was launched in 2012. This applies, for example, to the expansion of the Belgrade-Budapest railway line, the construction of the high-speed train between Milan, Venice and Trieste[133] and connections on the Adriatic-Baltic and Adriatic-North Sea axis. Poland, the Baltic States, Northern Europe and Central Europe are also connected to the maritime Silk Road through many links and are thus logistically networked via the Adriatic ports and Piraeus to East Africa, India and China. Overall, the ship connections for container transport between Asia and Europe will be reorganized. In contrast to the longer East Asia traffic via northwest Europe, the south-facing sea route through the Suez Canal towards the Trieste bridgehead shortens the transport of goods by at least four days.[134]

According to a study by the University of Antwerp, the maritime route via Trieste dramatically reduces transport costs. The example of Munich shows that the transport there from Shanghai via Trieste takes 33 days, while the northern route takes 43 days. From Hong Kong, the southern route reduces transport to Munich from 37 to 28 days. The shorter transport means, on the one hand, better use of the liner ships for the shipping companies and, on the other hand, considerable ecological advantages, also with regard to the lower CO2 emissions, because shipping is a heavy burden on the climate. Therefore, in the Mediterranean area, where the economic zone of the Liverpool–Milan Axis meets functioning railroad connections and deep-water ports, there are significant growth zones. Henning Vöpel, Director of the Hamburg World Economic Institute, recognizes that the North Range (i.e. transport via the North Sea ports to Europe) is not necessarily the one that will remain dominant in the medium term.[135]

From 2025, the Brenner Base Tunnel will also link the upper Adriatic with southern Germany. The port of Trieste, next to Gioia Tauro the only deep water port in the central Mediterranean for container ships of the seventh generation, is therefore a special target for Chinese investments. In March 2019, the China Communications Construction Company (CCCC) signed agreements to promote the ports of Trieste and Genoa. Accordingly, the port's annual handling capacity will be increased from 10,000 to 25,000 trains in Trieste (Trihub project) and a reciprocal platform to promote and handle trade between Europe and China will be created. It is also about logistics promotion between the North Adriatic port and Shanghai or Guangdong. This also includes a state Hungarian investment of 100 million euros for a 32 hectare logistics center and funding from the European Union of 45 million euros in 2020 for the development of the railway system in the port city.[136] Furthermore, the Hamburg port logistics group HHLA invested in the logistics platform of the port of Trieste (PLT) in September 2020.[137] In 2020, Duisburger Hafen AG (Duisport), the world's largest intermodal terminal operator, took a 15% stake in the Trieste freight terminal.[138] There are also further contacts between Hamburg, Bremen and Trieste with regard to cooperation.[139] There are also numerous collaborations in the Upper Adriatic, for example with the logistics platform in Cervignano.[140] In particular, the area of the upper Adriatic is developing into an extended intersection of the economic areas known as the Blue Banana and the Golden Banana. The importance of the free port of Trieste will continue to increase in the coming years due to the planned port expansion and the expansion of the Baltic-Adriatic railway axis (Semmering Base Tunnel, Koralm Tunnel and in the wider area Brenner Base Tunnel).[141][142][143]

Ice Silk Road

[edit]In addition to the Maritime Silk Road, Russia and China are reported to have agreed to jointly build an 'Ice Silk Road' along the Northern Sea Route in the Arctic, along a maritime route within Russian territorial waters.[144][145]

China COSCO Shipping Corp. has completed several trial trips on Arctic shipping routes, and Chinese and Russian companies are cooperating on oil and gas exploration in the area and to advance comprehensive collaboration on infrastructure construction, tourism and scientific expeditions.[145]

Digital Silk Road

[edit]In 2015, Xi announced the Digital Silk Road.[7]: 71 The Digital Silk Road is a component of the BRI which includes digital technological development, the development of digital standards, and the expansion of digital infrastructure.[146]: 177–188 Its stated aim is to improve digital connectivity among participating countries, with China as the main driver of the improved digital infrastructure, with the benefit to China of reducing its reliance on American digital technology.[147]: 205 It has also been called a way to export China's system of mass surveillance and censorship, according to rights group Article 19.[148][149]

Like the BRI more broadly, the Digital Silk Road is not monolithic and involves many actors across both China's public and private sectors.[147]: 205 Alibaba supplies a significant amount of technology for the Digital Silk Road.[150]: 272

China frames the Digital Silk Road as part of an effort to create a community of common destiny in cyberspace.[7]: 72 A key component of the strategy is to build digital infrastructure in areas of the global south where private providers have not been willing to develop infrastructure and where local governments do not have the capacity to do so.[7]: 76 China's willingness to develop digital infrastructure in such locations is in part due to the expectation that future population growth will be especially high in global south regions.[7]: 76–77

As part of the Digital Silk Road, China built 34 terrestrial cables and dozens of underwater cables within 12 BRI countries in Asia, Africa, and Europe over the period 2017–2022.[146]: 180 Digital Silk Road-related investments in projects outside China reached an estimated US$79 billion as of 2018.[147]: 205

At the opening ceremony of the first Belt and Road Forum, Xi Jinping emphasized the importance of developing a Digital Silk Road through innovation in intelligent cities concepts, the digital economy, artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, and quantum computing.[146]: 77

The Eurasian Economic Union cooperates with China on the development of the Digital Silk Road.[151]: 187 Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Belarus are actively involved in the Digital Silk Road while Russia incorporated Chinese technologies into its digital infrastructure.[152]

Super grid

[edit]The super grid project aims to develop six ultra high voltage electrical grids across China, Northeast Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, Central Asia and West Asia. The wind power resources of Central Asia would form one component of this grid.[153][154]

Additionally proposed

[edit]The Bangladesh–China–India–Myanmar Economic Corridor (BCIM) was proposed to run from southern China to Myanmar and was initially officially classified as "closely related to the Belt and Road Initiative".[155] Since the second Belt and Road Forum in 2019, BCIM has been dropped from the list of projects due to India's refusal to participate in the Belt and Road Initiative.[156]

Projects

[edit]

China has engaged 149[158] countries and 30 international organizations in the BRI.[159] Infrastructure projects include ports, railways, highways, power stations, aviation and telecommunications.[160] The flagship projects include the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor, the Boten–Vientiane railway in Laos and Khorgos land port.[161][162][163] The launch of the China-Europe Freight Train (CEFT) preceded the BRI but was later incorporated into the BRI.[7]: 120

Interpretations of which projects are part of the BRI can differ because the Chinese government does not publish a comprehensive list of projects.[7]: 60–61 The Chinese Academy of Sciences takes a narrow definition, including only projects derived from, or included in, cooperation dialogues between China and other BRI countries.[164]: 223

Corruption scandals

[edit]There is limited data on corruption involving the BRI in Chinese government sources.[165] In response to public corruption scandals such as the bribery and money laundering conviction of BRI advocate Patrick Ho, in 2019, the CCP's Central Commission for Discipline Inspection announced that it would embed officers in countries participating in the BRI.[166] A 2021 analysis by AidData at the College of William & Mary found that Pakistan, Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Papua New Guinea, Cambodia, Mozambique, and Belarus, were the top countries for reported corruption scandals involving BRI projects.[167]

Ecological issues

[edit]Approximately 54% of the BRI's energy projects are in clean energy or alternative energy sectors.[84]: 216

The Belt and Road initiative has attracted attention and concern from environmental organizations. A joint report by the World Wide Fund for Nature and HSBC argued that the BRI presents significant risks as well as opportunities for sustainable development. These risks include the overuse of natural resources, the disruption of ecosystems, and the emission of pollutants.[168] Coal-fired power stations, such as Emba Hunutlu power station in Turkey, are being built as part of BRI, thus increasing greenhouse gas emissions and global warming.[169] Glacier melting as a result of excess greenhouse gas emissions, endangered species preservation, desertification and soil erosion as a result of overgrazing and over farming, mining practices, water resource management, and air and water pollution as a result of poorly planned infrastructure projects are some of the ongoing concerns as they relate to Central Asian nations.[170]

A point of criticism of the BRI overall relates to the motivation of pollution and environmental degradation outsourcing to poorer nations, whose governments will disregard the consequences. In Serbia, for instance, where pollution-related deaths already top Europe, the presence of Chinese-owned coal-powered plants have resulted in an augmentation in the country's dependency on coal, as well as air and soil pollution in some towns.[171] BRI coal projects accounted for as much as 42% of China's overseas investment in 2018,[172] and 93% of energy investments of the BRI-linked Silk Road Fund go to fossil fuels.[173]

The development of port infrastructure and increasing shipping associated with the maritime Belt and Road Initiative could impact sensitive species and marine habitats like coral reefs, mangroves, seagrass meadows and saltmarsh.[174]

A report by the United Nations Development Programme and the China Center for International Economic Exchanges frame the BRI as an opportunity for environmental protection so long as it is used to provide green trade, finance, and investment in alignment with each country's implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals.[175] Other proposals include providing financial support for BRI member countries aiming to fulfill their contribution to the Paris Agreement, or providing resources and policy expertise to aid the expansion of renewable energy sources such as solar power in member countries.[176][177]

China views the concept of ecological civilization as part of the BRI.[7]: 85

The Belt and Road Initiative International Green Development Coalition (BRIGC) was launched during the 2nd Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in April 2019.[56]: 60 It aims to "integrate sustainable development, in particular environmental sustainability, international standards and best practices, across the... priorities of the Belt and Road Initiative".[178][179][180] However, many scholars are unsure whether these best practices will be implemented. All BRI-specific environmental protection goals are outlined in informal guidelines rather than legally binding policies or regulations.[176][181] Moreover, member nations may choose to prioritize economic development over environmental protections, leading them to neglect to enforce environmental policy or lower environmental policy standards.[182] This could cause member nations to become "pollution havens" as Chinese domestic environmental protections are strengthened, though evidence of this currently happening is limited.[183][184]

Based on the most recent report from the Green Finance and Development center, which reports on the environmental progress of Belt and Road Initiative investment, there is evidence which shows that China has been successful in following the informal guidelines laid out by the BRIGC.[185] Many of the southeast Asia and eastern Europe countries that China seeks to work with through the BRI prioritize sustainable development.[7]: 87 China has responded by emphasizing a "Green Silk Road" and promoting harmony between humanity and the environment.[7]: 87 Chinese BRI investment in 2023 show that the year has been China's “greenest” yet since the project's inception when it comes to clean energy investment.[186] China made its largest ever contribution to investment in the green-energy sector, with US$7.9 billion being devoted to solar and wind power development, with projects being built in Brazil and Indonesia.[187][185][188] A further US$1.9 billion was invested in hydropower industry, including BRI hydroelectric dam projects in Cambodia, Pakistan, Uganda, Tajikistan, Georgia, Myanmar and Indonesia.[7]: 86 [185] There are additional solar and wind farm projects in Kazakhstan and Pakistan.[7]: 86

In September 2021, Xi Jinping announced that his country will "step up support" for developing countries to adopt "green and low-carbon energy" and will no longer be financing overseas coal-fired power plants.[189] Xi has seemingly failed to live up to this pledge, as there has been expressed interest by China in providing financial and technically support for new coal-fired power projects. In January 2023, Pakistan announced that it had approved the construction of a Chinese-funded 300 MW coal-fired power plant in Gwadar, Pakistan.[190] More recently in January 2024, a 380 MW coal-fired power plant started operation in Sulawesi, Indonesia.[185]

Allegations of human rights violations

[edit]A 2021 analysis by AidData at the College of William & Mary found that 35 percent of BRI infrastructure projects have encountered "major implementations problems" such as labor violations, corruption, environmental hazards, and public protests.[191][167]

According to a report by American NGO China Labor Watch, there are widespread human rights violations concerning Chinese migrant workers sent abroad. The Chinese companies allegedly "commit forced labor" and usually confiscate the workers' passports once they arrive in another country, make them apply for illegal business visas and threaten to report their illegal status if they refuse to comply, refuse to give adequate medical care and rest, restrict workers' personal freedom and freedom of speech, force workers to overwork, cancel vacations, delay the payment of wages, publish deceptive advertisements and promises, browbeat workers with high amount of damages if they intend to leave, provide bad working and living conditions, punish workers who lead protests and so on.[192][193]

Table of BRI investment by country from 2014 to 2018

[edit]| Country | Construction | Country | Investment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 31.9 | 24.3 | ||

| 23.2 | 14.1 | ||

| 17.5 | 10.4 | ||

| 16.8 | 9.4 | ||

| 15.8 | 8.1 | ||

| 15.3 | 7.9 | ||

| 14.7 | 7.6 |

Reactions

[edit]Generally, it is more important for China to persuade its domestic audiences of the benefits of BRI than it is to persuade foreign audiences at-large.[17]: 148 Academic Jeremy Garlick writes that this is a reason why the Chinese government presents the BRI in a way more intuitively understandable to domestic than global audiences.[17]: 148

Former EU diplomat Bruno Maçães describes the BRI as the world's first transnational industrial policy because it goes beyond national policy to influence the industrial policy of other states.[7]: 165

Support

[edit]As of 2020, more than 130 countries had issued endorsements.[5] UN Secretary General António Guterres has described the BRI as capable of accelerating the UN Sustainable Development Goals.[7]: 164 Institutional connections between the BRI and multiple UN bodies have also been established.[7]: 164

In June 2016, Xi Jinping visited Poland and met with Poland's President Andrzej Duda and Prime Minister Beata Szydło.[196][197] Duda and Xi signed a declaration on strategic partnership in which they reiterated that Poland and China viewed each other as long-term strategic partners.[198]

As a wealthy country, Singapore does not need massive external financing or technical assistance for domestic infrastructure building, but has repeatedly endorsed the BRI and cooperated in related projects in a quest for global relevance and to strengthen economic ties with BRI recipients. It is also one of the largest investors in the project. Furthermore, there is a strategic defensive factor: making sure a single country is not the single dominant factor in Asian economics.[199]

While the Philippines historically has been closely tied to the United States, China sought its support for the BRI in terms of the quest for dominance in the South China Sea. The Philippines adjusted its policy in favor of Chinese claims in the South China Sea under President Rodrigo Duterte.[200]

In 2017, Yanis Varoufakis, the former Greek Minister of Finance, wrote in Project Syndicate that his experience with the Belt and Road Initiative has been highly encouraging.[201] He remarked that the Chinese authorities managed to combine their sense of self-interest with a patient investment attitude and a genuine commitment to negotiate over and over again, in order to achieve a mutually advantageous agreement.[201]

In April 2019 and during the second Arab Forum for Environment and Development, China engaged in an array of partnerships called "Build the Belt and Road, Share Development and Prosperity" with 18 Arab countries. The general stand of African countries sees BRI as a tremendous opportunity for independence from foreign aid and influence.[202]

Greece, Croatia, and 14 other Eastern European countries are already dealing with China within the framework of the BRI. In March 2019, Italy was the first member of the Group of Seven nations to join the BRI. The new partners signed a Memorandum of Understanding worth €2.5 billion across an array of sectors such as transport, logistics, and port infrastructure.[203]

Despite initially criticizing BRI, the former Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad pledged support for the BRI project in 2019.[204]: 54 He stated that he was fully in support of the Belt and Road Initiative and that his country would benefit from BRI. "Yes, the Belt and Road idea is great. It can bring the land-locked countries of Central Asia closer to the sea. They can grow in wealth and their poverty reduced," Mahathir said.[205]

Russian political scientist Sergey Karaganov argues that the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) and China's Belt and Road Initiative will work together to promote economic integration throughout the region.[206]

Opposition

[edit]Some observers and skeptics, mainly from non-participant countries, including the United States, interpret it as a plan for a Sinocentric international trade network.[207][208] In response the United States, Japan, and Australia had formed a counter initiative, the Blue Dot Network in 2019, followed by the G7's Build Back Better World initiative in 2021.[209][210]

The United States proposes a counter-initiative called the "Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy" (FOIP). US officials have articulated the strategy as having three pillars: security, economics, and governance.[211] At the beginning of June 2019, there has been a redefinition of the general definitions of "free" and "open" into four stated principles: respect for sovereignty and independence; peaceful resolution of disputes; free, fair, and reciprocal trade; and adherence to international rules and norms.[212]

Government officials in India have repeatedly objected to China's Belt and Road Initiative.[213] In particular, they believe the "China–Pakistan Economic Corridor" (CPEC) project ignores New Delhi's essential concerns about its sovereignty and territorial integrity.[214]

Former Malaysian prime minister Mahathir Mohamad had initially found the terms of BRI to be too harsh for most countries and recommended countries avoid joining the BRI, but has changed his stance since.[215][216]

According to a report by Reuters, in 2019 the United States Central Intelligence Agency began a clandestine campaign on Chinese social media to spread negative narratives about the Xi Jinping administration in an effort to influence Chinese public opinion against the government. The CIA promoted narratives that CCP leaders were hiding money overseas and that the BRI was corrupt and wasteful. As part of the campaign, the CIA also targeted foreign countries where the United States and China compete for influence.[217][218]

Mixed

[edit]Vietnam historically has been at odds with China, so it has been indecisive about supporting or opposing BRI.[219] In December 2023, Vietnam and China agreed a number of cooperation documents, including one related to the BRI.[220]

South Korea has tried to develop the "Eurasia Initiative" (EAI) as its own vision for an east–west connection. In calling for a revival of the ancient Silk Road, the main goal of President Park Geun-hye was to encourage a flow of economic, political, and social interaction from Europe through the Korean Peninsula. Her successor, President Moon Jae-in announced his own foreign policy initiative, the "New Southern Policy" (NSP), which seeks to strengthen relations with Southeast Asia.[221]

In 2017, former secretary of state Henry Kissinger stressed that cooperation between the US and Chinese governments was preferable to a race towards a new cold war. In his view the United States should embed itself into the Belt and Road Initiative by way of joining the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which would allow the United States to legitimately object to Chinese diplomatic over-reach.[222][223]

While Italy and Greece have joined the Belt and Road Initiative, other European countries have voiced ambivalent opinions. German chancellor Angela Merkel declared that the BRI "must lead to a certain reciprocity, and we are still wrangling over that bit". In January 2019, French president Emmanuel Macron said, "the ancient Silk Roads were never just Chinese … New roads cannot go just one way."[203] European Commission Chief Jean-Claude Juncker and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe signed an infrastructure agreement in Brussels in September 2019 to counter China's Belt and Road Initiative and link Europe and Asia to coordinate infrastructure, transport, and digital projects.[224][225]

In 2018, the premier of the south-eastern Australian state of Victoria, Daniel Andrews, signed a memorandum of understanding on the Belt and Road Initiative to establish infrastructure ties and further relations with China.[226][227] Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton described the BRI as "a propaganda initiative from China" that brings an "enormous amount of foreign interference", while arguing that "Victoria needs to explain why it is the only state in the country that has entered into this agreement". Prime Minister Scott Morrison said Victoria was stepping into federal government policy territory, stating "We didn't support that decision at the time [the Victoria State Government and the National Development and Reform Commission of the People's Republic of China] made [the agreement]. National interest issues on foreign affairs are determined by the federal government, and I respect their jurisdiction when it comes to the issues they're responsible for, and it's always been the usual practice for states to respect and recognise the role of the federal government in setting foreign policy". In April 2021, Foreign Minister Marise Payne declared Australia would pull out of the Belt and Road Initiative, cancelling Victoria's agreements signed with China, and pulling out of the "Belt and Road" initiative completely.[228][227][229][230] The federal government's decision to veto the deal reflected the increasingly soured relationship between the Australian Government and the Chinese Government, after China's alleged attempts to employ economic coercion[231] in response to the Australian Government's support for an inquest into the origins of COVID-19,[232] as well as the Australian Government's decision to support the US in several regional disputes opposing China, such as the issue of Taiwan[233] or the South China Sea.[234]

In October 2024, Brazil opted against joining the BRI.[235][236]

Accusations of neo-colonialism and debt-trap diplomacy

[edit]

Accusations

[edit]Some, including Western governments,[237] have accused the Belt and Road Initiative of being a form of neo-colonialism, due to what they allege is China's practice of debt-trap diplomacy to fund the initiative's infrastructure projects.[238] The concept of debt-trap diplomacy was first coined by an Indian think tank, the New Delhi-based Centre for Policy Research, before being picked up and expanded on by papers by two Harvard students, which subsequently gained media attention in the mainstream press.[239]

China contends that the initiative has provided markets for commodities, improved prices of resources, and thereby reduced inequalities in exchange, improved infrastructure, created employment, stimulated industrialization, and expanded technology transfer, thereby benefiting host countries.[240]

Tanzanian President John Magufuli said the loan agreements of BRI projects in his country were "exploitative and awkward".[241] He said Chinese financiers set "tough conditions that can only be accepted by mad people," because his government was asked to give them a guarantee of 33 years and an extensive lease of 99 years on a port construction. Magufuli said Chinese contractors wanted to take the land as their own, but his government had to compensate them for drilling the project construction.[242]

In May 2021, DRC's President Félix Tshisekedi called for a review of mining contracts signed with China by his predecessor Joseph Kabila,[243] in particular, the Sicomines multibillion-dollar 'minerals-for-infrastructure' agreement.[244][245][246] China's plans to link its western Xinjiang province to Gwadar in the Balochistan province of Pakistan with its US$500m investment in the Gwadar Port has met resistance from local fishermen protesting against Chinese trawlers and illegal fishing.[247][248]

Rebuttals

[edit]Deborah Bräutigam, a professor at the School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) at Johns Hopkins University, described the debt-trap diplomacy theory as a "meme" that became popular due to "human negativity bias" based on anxiety about the rise of China.[16] A 2019 research paper by Bräutigam revealed that most of the debtor countries voluntarily signed on to the loans and had positive experiences working with China, and "the evidence so far, including the Sri Lankan case, shows that the drumbeat of alarm about Chinese banks' funding of infrastructure across the BRI and beyond is overblown" and "a large number of people have favorable opinions of China as an economic model and consider China an attractive partner for their development."[16] She said that the theory lacked evidence and criticized the media for promoting a narrative that "wrongfully misrepresents the relationship between China and the developing countries that it deals with," highlighting the fact that Sri Lanka owed more to Japan, the World Bank, and the Asian Development Bank than to China.[249] A 2018 China Africa Research Initiative report, co-authored by Bräutigam, remarked that "Chinese loans are not currently a major contributor to debt distress in Africa."[250]

According to New York-based economist Anastasia Papadimitriou, partnering countries are equally responsible when making deals with China. China's alleged "neocolonialist intentions" can be disproved by Sri Lanka's Hambantota Port project on the southeast coast of Sri Lanka, one of the most cited examples of debt-trap diplomacy.[251] After an analysis of the Belt and Road Initiative, Papadimitriou concludes that it is "not so much neocolonialism, rather it is economic regionalism".[251] Additionally, The Royal Institute of International Affairs, a London-based international affairs think tank, asserted that the debt crisis in Sri Lanka was unrelated to Chinese lending, but was instead caused mainly from "the misconduct of local elites and Western-dominated financial markets".[252] It was confirmed by Lowy Institute. A 2019 report by the Lowy Institute said that China had not engaged in deliberate actions in the Pacific which justified accusations of debt-trap diplomacy (based on contemporaneous evidence), and China had not been the primary driver behind rising debt risks in the Pacific; the report expressed concern about the scale of the country's lending, however, and the institutional weakness of Pacific states which posed the risk of small states being overwhelmed by debt.[253] A 2020 Lowy Institute article called Sri Lanka's Hambantota International Port the "case par excellence" for China's debt-trap diplomacy, but called the narrative a "myth" because the project was proposed by former Sri Lankan president Mahinda Rajapaksa, not Beijing.[254] The article added that Sri Lanka's debt distress was not caused by Chinese lending, but by "excessive borrowing on Western-dominated capital markets."[254]

The Rhodium Group, an American research company, analyzed Chinese debt renegotiations and concluded that China's leverage in them are often exaggerated and realistically limited in power. The findings of their study frequently showed an outcome in favor of the borrower rather than the supposedly predatory Chinese lender. The firm found that "asset seizures are a very rare occurrence" and that instead debt write-off was the most common outcome.[255]

Darren Lim, senior lecturer at the Australian National University, said that the debt-trap diplomacy claim was never credible, despite the first Trump administration pushing it.[256] Dawn C. Murphy, Professor of International Security Studies at the USAF Air War College, concludes that describing China's behavior as "neocolonialist" is an "exaggeration and misrepresentation".[67]: 158

According to political scientist and researcher Zhexin Zhang, the overwhelming enthusiasm of developing countries in the Belt and Road Initiative, as seen first in the "Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation" held in May 2017, is sufficient to invalidate the neo-colonialism argument.[257]

A March 2018 study released by the Center for Global Development, a Washington-based think tank, remarks that between 2001 and 2017, China restructured or waived loan payments for 51 debtor nations, the majority of BRI participants, without seizing state assets.[258] The study concluded that in most cases, it was unlikely that there would be severe problems with debt.[17]: 87 In September 2018, W. Gyude Moore, a former Liberian public works minister and senior policy fellow at the Center for Global Development, stated that "[t]he language of "debt-trap diplomacy" resonates more in Western countries, especially the United States, and is rooted in anxiety about China's rise as a global power rather than in the reality of Africa."[259] He also stated that "China has been a net positive partner with most African countries."[260] According to Pradumna Bickram Rana and Jason Ji Xianbai of Singapore's Nanyang Technological University, although there is a number of implementation issues confronting the Belt and Road Initiative mostly due to the COVID-19 Pandemic, China's alleged debt-trap diplomacy "more myth than reality".[261] While they acknowledge that various countries are facing difficulties in paying their debts to China, they highlight China's willingness to help these countries restructure their debt through forgiving policies, such as partial debt relief.[261] In eleven cases, China postponed loans for indebted countries, one being Tonga.[256]

Writing in 2023, academic Süha Atatüre stated that United States opposition to the Belt and Road Initiative stems from the fact that it lacks the capacity to implement a rival project.[262]: 40

Publishing in 2023, academic Austin Strange concludes that scholars have challenged the narrative of a Chinese debt-trap and that analysis of BRI projects does not substantiate the debt-trap narrative.[263]: 15–16 On the issue of criticism of the BRI more broadly, Strange writes that unintended negative consequences can result from global infrastructure projects generally (citing examples of issues arising from overseas projects by Japan and South Korea) and are not a BRI-specific or China-specific challenge.[263]: 58–59

Academics Yan Hairong and Barry Sautman stated in a 2024 study that the debt-trap narrative is incorrect, as China does not foreclose on borrower assets.[164]: 223

London School of Economics Professor Keyu Jin writes that the claim that China leads borrowers into a debt trap is misleading.[48]: 280 Jin observes that the majority of BRI countries' debt is owed to international organizations or private institutions like hedge funds, rather than to China.[48]: 280–281 Jin also writes that China has written off many of its loans and also provided debt relief to borrowers.[48]: 281

Country-specific

[edit]Through the BRI, China has a major role in infrastructure development in Cambodia.[204]: 29 In 2017, China financed approximately 70% of Cambodia's road and bridge development.[204]: 29 China built a major expressway between Sihanoukville and Phnom Penh, which began operating in 2023.[204]: 29 As of at least 2024, the expressway is the largest BRI project in Cambodia.[7]: 132

Chinese leadership describes Ethiopia as a bridge between the Belt and Road Initiative and Africa's development, stating that the relationship between the two countries is a model of South-South cooperation and "a pilot program for China-Africa production capacity cooperation."[164]: 222–223

Greece hosts the most successful BRI port project as of at least 2024, the port at Piraeus.[7]: 67 The port's incorporation as part of the BRI has been one of the mechanisms through which China has strengthened its relationship with Greece, following the increased strain in the European Union-Greece relationship after Greece's bailout.[7]: 67

As of at least 2024, Hungary and Serbia are also two of the major European supporters of the BRI.[264]

Italy was the only G7 country which had been a partner in the development of the BRI, having been involved since March 2019, but in July 2023 declared its intention to quit the BRI.[265] Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni stated that the project was not of any real benefit to Italy's economy.[266]

The China-Laos Railway is one of the most sectorally integrated of the major BRI projects.[7]: 129 It has brought together expertise in large-scale engineering, finance, construction, and economic design.[7]: 129 The Boten-Ventiane Railway is the Laos section of the broader railway, which is in turn part of the China-Laos Economic Corridor.[7]: 129 The railway's high speed trains travel at 160 km per hour and have reduced travel time from Ventiane to Luang Prabang to two hours, down from a day or more before the railway.[204]: 39

Due to its opposition to the Gwadar Port City in Pakistan, in 2019 the Baloch Liberation Army targeted Chinese nationals in an attack at the Pearl-Continental Hotel.[7]: 60

During a November 2024 visit by Xi to Peru, Boluarte and Xi celebrated the opening of the Chancay port, which is part of the Belt and Road Initiative.[267] Xi described the port as the beginning of a new maritime-land corridor between China and Latin America.[267] The port was built by COSCO Shipping Ports.[267]

In Thailand, the public views BRI projects, particularly railways, positively.[204]: 34–35

Belt and Road educational policy

[edit]Along with policy coordination, facilities connectivity, unimpeded trade and financial integration, people-to-people bonds are among the five major goals of BRI.[268] BRI educational component implies mutual recognition of qualifications, academic mobility and student exchanges, coordination on education policy, life-long learning, and development of joint study programmes.[269][270] To this end, Xi Jinping announced plan to allocate funds for additional 30,000 scholarships for SCO citizens and 10,000 scholarships for the students and teachers along the Road.[271] The Silk Road Scholarship is part of China's broader agenda of increasing academic and cultural cooperation with BRI-participating countries.[18]: 158

Among the BRI cooperation priorities is also strengthening people-to-people ties through academic mobility, research cooperation, and student exchanges.[272] Since the beginning of the BRI, China has occupied a key role in shaping how academic, and skilled migration in general, develops along the BRI and increased efforts to attract and retain foreign talents.[272]

The University Alliance of the Silk Road centered at Xi'an Jiaotong University aims to support the Belt and Road initiative with research and engineering.[273] A French think tank, Fondation France Chine (France-China Foundation), focused on the study of the New Silk Roads, was launched in 2018. It is described as pro–Belt and Road Initiative and pro-China.[274][275]

See also

[edit]- Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation

- Asia-Africa Growth Corridor

- Asian Highway Network

- Blue Banana

- Blue Dot Network – counter-initiative by the United States

- Build Back Better World – counter-initiative by the G7

- India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor

- China-Arab States Cooperation Forum

- Eurasian Land Bridge

- Eurasia Continental Bridge corridor

- Forum on China-Africa Cooperation

- Golden Banana

- International North–South Transport Corridor

- Southern Ocean – See Category: Ports and harbors of Antarctica

- Ports of the Baltic Sea

- Channel Ports – ports and harbours of the English Channel

- List of North Sea ports – ports of the North Sea and its influent rivers

- List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Wǒ wěi děng yǒuguān bùmén guīfàn "Yīdài Yīlù" chàngyì Yīngwén yì fǎ" 我委等有关部门规范"一带一路"倡议英文译法 [Regulations on the English translation of "Belt and Road" Initiative by our Commission and related departments]. ndrc.gov.cn (in Chinese (China)). National Development and Reform Commission. 11 May 2019. Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ "China's Massive Belt and Road Initiative". Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ "Belt and Road Initiative". World Bank. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ a b c Kuo, Lily; Kommenda, Niko (30 July 2018). "What is China's Belt and Road Initiative?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 September 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2018.