Energy crisis

An energy crisis or energy shortage is any significant bottleneck in the supply of energy resources to an economy. In literature, it often refers to one of the energy sources used at a certain time and place, in particular, those that supply national electricity grids or those used as fuel in industrial development. Population growth has led to a surge in the global demand for energy in recent years. In the 2000s, this new demand – together with Middle East tension, the falling value of the US dollar, dwindling oil reserves, concerns over peak oil, and oil price speculation – triggered the 2000s energy crisis, which saw the price of oil reach an all-time high of $147.30 per barrel ($926/m3) in 2008.[citation needed]

Most energy crises have been caused by localized shortages, wars and market manipulation. However, the recent historical energy crises listed below were not caused by such factors.

Causes

[edit]

Most energy crises have been caused by localized shortages, wars and market manipulation. Some have argued that government actions like tax hikes, nationalisation of energy companies, and regulation of the energy sector shift supply and demand of energy away from its economic equilibrium.[1] However, the recent historical energy crises listed below were not caused by such factors. Market failure is possible when monopoly manipulation of markets occurs. A crisis can develop due to industrial actions like union organized strikes or government embargoes. The cause may be over-consumption, aging infrastructure, choke point disruption, or bottlenecks at oil refineries or port facilities that restrict fuel supply. An emergency may emerge during very cold winters due to increased consumption of energy.

Large fluctuations and manipulations in future derivatives can impact price. Investment banks trade 80% of oil derivatives as of May 2012, compared to 30% a decade ago.[2] This consolidation of trade contributed to an improvement of global energy output from 117,687 TWh in 2000 to 143,851 TWh in 2008.[3] Limitations on free trade for derivatives could reverse this trend of growth in energy production. Kuwaiti Oil Minister Hani Hussein stated that "Under the supply and demand theory, oil prices today are not justified," in an interview with Upstream.[4]

Pipeline failures and other accidents may cause minor interruptions to energy supplies. A crisis could possibly emerge after infrastructure damage from severe weather. Attacks by terrorists or militia on important infrastructure are a possible problem for energy consumers, with a successful strike on a Middle East facility potentially causing global shortages. Political events, for example, when governments change due to regime change, monarchy collapse, military occupation, and coup may disrupt oil and gas production and create shortages. Fuel shortage can also be due to the excess and useless use of the fuels.

Historical crises

[edit]- North Korea has had energy shortages for many years.

- Zimbabwe has experienced a shortage of energy supplies for many years due to financial mismanagement.

20th century

[edit]- 1970s energy crisis – caused by the peaking of oil production in major industrial nations (Germany, United States, Canada, etc.) and embargoes from other producers

- 1973 oil crisis – caused by an OAPEC oil export embargo by many of the major Arab oil-producing states, in response to Western support of Israel during the Yom Kippur War

- 1979 oil crisis – caused by the Iranian Revolution

- 1990 oil price shock – caused by the Gulf War

2000s

[edit]- 2000 fuel protests in the United Kingdom in 2000 were caused by a rise in the price of crude oil combined with already relatively high taxation on road fuel in the UK.

- 2000s energy crisis – Since 2003, a rise in prices caused by continued global increases in petroleum demand coupled with production stagnation, the falling value of the US dollar, and a myriad of other secondary causes.

- 2000–2001 California electricity crisis – Caused by market manipulation by Enron and failed deregulation; resulted in multiple large-scale power outages

- 2000–2008 North American natural gas crisis

- 2004 energy crisis in Argentina

- 2005, 2008 China experienced severe energy shortages towards the end of 2005 and again in early 2008. During the latter crisis they suffered severe damage to power networks along with diesel and coal shortages.[5] Supplies of electricity in Guangdong province, the manufacturing hub of China, are predicted to fall short by an estimated 10 GW.[6] In 2011 China was forecast to have a second quarter electrical power deficit of 44.85 – 49.85 GW.[7]

- 2007 Political riots occurring during the 2007 Burmese anti-government protests were sparked by rising energy prices.

- 2008 energy crisis in Central Asia, caused by abnormally cold temperatures and low water levels in an area dependent on hydroelectric power. At the same time the South African President was appeasing fears of a prolonged electricity crisis in South Africa.[8]

- 2008. In February, the President of Pakistan announced plans to tackle energy shortages that were reaching crisis stage, despite having significant hydrocarbon reserves.[9] In April 2010, the Pakistani government announced the Pakistan national energy policy, which extended the official weekend and banned neon lights in response to a growing electricity shortage.[10]

- 2008 South African energy crisis. The South African crisis led to large price rises for platinum in February 2008 and reduced gold production.[11] and continues as of 2023.

2010s

[edit]- 2012 United Kingdom fuel crisis

- 2015 – Nepal experienced a major energy crisis in 2015 when India imposed an economic blockade on Nepal. Nepal faced shortages of various kinds of petroleum products and food materials which severely affected Nepal's economy.

- 2017 – The Gaza electricity crisis is a result of the tensions between Hamas, which rules the Gaza Strip, and the Palestinian Authority/Fatah, which rules the West Bank over custom tax revenue, funding of the Gaza Strip, and political authority. Residents receive electricity for a few hours a day on a rolling blackout schedule.[12][13][14][15]

- 2019 California energy crisis

2020s

[edit]

- 2021 Texas power crisis

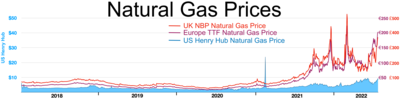

- 2021 United Kingdom natural gas supplier crisis and 2021 United Kingdom fuel supply crisis

- 2021 global energy crisis. The record-high energy prices were driven by a global surge in demand as the world quit the economic recession caused by COVID-19 pandemic, particularly due to strong energy demand in Asia.[16][17][18]

- The Lebanese liquidity crisis lead to shortages of fuel for electricity plants, resulting in the 2021 Lebanese blackout and public utilities being able to offer power for only a few hours a day.[19]

- Ukrainian energy crisis

Emerging oil shortage

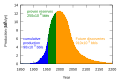

[edit]"Peak oil" is the period when the maximum rate of global petroleum extraction is reached, after which the rate of production enters terminal decline. It relates to a long-term decline in the available supply of petroleum. This, combined with increasing demand, significantly increases the worldwide prices of petroleum-derived products. Most significant is the availability and price of liquid fuel for transportation.

The US Department of Energy in the Hirsch report indicates that "The problems associated with world oil production peaking will not be temporary, and past 'energy crisis' experience will provide relatively little guidance."[20]

Mitigation efforts

[edit]To avoid the serious social and economic implications a global decline in oil production could entail, the 2005 Hirsch report emphasized the need to find alternatives, at least ten to twenty years before the peak, and to phase out the use of petroleum over that time. Such mitigation could include energy conservation, fuel substitution, and the use of unconventional oil. Because mitigation can reduce the use of traditional petroleum sources, it can also affect the timing of peak oil and the shape of the Hubbert curve.

Energy policy may be reformed leading to greater energy intensity, for example in Iran with the 2007 Gas Rationing Plan in Iran, Canada and the National Energy Program and in the US with the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 also called the Clean Energy Act of 2007. Another mitigation measure is the setup of a cache of secure fuel reserves like the United States Strategic Petroleum Reserve, in case of national emergency. Chinese energy policy includes specific targets within their 5-year plans.

Andrew McKillop has been a proponent of a contract and converge model or capping scheme, to mitigate both emissions of greenhouse gases and a peak oil crisis. The imposition of a carbon tax would have mitigating effects on an oil crisis.[citation needed] The Oil Depletion Protocol has been developed by Richard Heinberg to implement a powerdown during a peak oil crisis. While many sustainable development and energy policy organisations have advocated reforms to energy development from the 1970s, some cater to a specific crisis in energy supply including Energy-Quest and the International Association for Energy Economics. The Oil Depletion Analysis Centre and the Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas examine the timing and likely effects of peak oil.

Ecologist William Rees believes that

To avoid a serious energy crisis in coming decades, citizens in the industrial countries should actually be urging their governments to come to an international agreement on a persistent, orderly, predictable, and steepening series of oil and natural gas price hikes over the next two decades.

Due to a lack of political viability on the issue, government-mandated fuel prices hikes are unlikely and the unresolved dilemma of fossil fuel dependence is becoming a wicked problem. A global soft energy path seems improbable, due to the rebound effect. Conclusions that the world is heading towards an unprecedented large and potentially devastating global energy crisis due to a decline in the availability of cheap oil lead to calls for a decreasing dependency on fossil fuel.

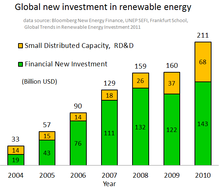

Other ideas concentrate on design and development of improved, energy-efficient urban infrastructure in developing nations.[21] Government funding for alternative energy is more likely to increase during an energy crisis, so too are incentives for oil exploration. For example, funding for research into inertial confinement fusion technology increased during the 1970s.

Kirk Sorensen and others[22] have suggested that additional nuclear power plants, particularly liquid fluoride thorium reactors have the energy density to mitigate global warming and replace the energy from peak oil, peak coal and peak gas. The reactors produce electricity and heat so much of the transportation infrastructure should move over to electric vehicles. However, the high process heat of the molten salt reactors could be used to make liquid fuels from any carbon source.

Social and economic effects

[edit]The macroeconomic implications of a supply shock-induced energy crisis are large, because energy is the resource used to exploit all other resources. Oil price shocks can affect the rest of the economy through delayed business investment,[23] sectoral shifts in the labor market,[24] or monetary policy responses.[25] When energy markets fail, an energy shortage develops. Electricity consumers may experience intentionally engineered rolling blackouts during periods of insufficient supply or unexpected power outages, regardless of the cause.

Industrialized nations are dependent on oil, and efforts to restrict the supply of oil would have an adverse effect on the economies of oil producers. For the consumer, the price of natural gas, gasoline (petrol) and diesel for cars and other vehicles rises. An early response from stakeholders is the call for reports, investigations and commissions into the price of fuels. There are also movements towards the development of more sustainable urban infrastructure.

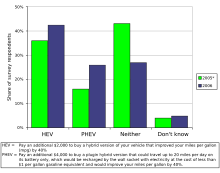

In the market, new technology and energy efficiency measures become desirable for consumers seeking to decrease transport costs.[27] Examples include:

- In 1980 Briggs & Stratton developed the first gasoline hybrid electric automobile; also appearing are plug-in hybrids.

- the growth of advanced biofuels.

- innovations like the Dahon, a folding bicycle

- modernized and electrifying passenger transport

- Railway electrification systems and new engines such as the Ganz-Mavag locomotive

- variable compression ratio for vehicles

Other responses include the development of unconventional oil sources such as synthetic fuel from places like the Athabasca Oil Sands, more renewable energy commercialization and use of alternative propulsion. There may be a relocation trend towards local foods and possibly microgeneration, solar thermal collectors and other green energy sources.

Tourism trends and gas-guzzler ownership varies with fuel costs. Energy shortages can influence public opinion on subjects from nuclear power plants to electric blankets. Building construction techniques—improved insulation, reflective roofs, thermally efficient windows, etc.—change to reduce heating costs.

The percentage of businesses indicating that energy prices represent a barrier to investment has increased in 2022 (82%) as found in recent surveys, particularly for those who see it as a significant obstacle (59%). According to varied energy prices and energy intensity across nations and industries, various countries have different percentages of businesses that view energy costs as a key obstacle, ranging from 24% in Finland to 81% in Greece for example.[28]

Crisis management

[edit]An electricity shortage is felt most acutely in heating, cooking, and water supply. Therefore, a sustained energy crisis may become a humanitarian crisis. If an energy shortage is prolonged a crisis management phase is enforced by authorities. Energy audits may be conducted to monitor usage. Various curfews with the intention of increasing energy conservation may be initiated to reduce consumption. For example, to conserve power during the Central Asia energy crisis, authorities in Tajikistan ordered bars and cafes to operate by candlelight."Crisis Looms as Bitter Cold, Blackouts Hit Tajikistan". NPR. Retrieved 10 February 2008.

In the worst kind of energy crisis energy rationing and fuel rationing may be incurred. Panic buying may beset outlets as awareness of shortages spread. Facilities close down to save on heating oil; and factories cut production and lay off workers. The risk of stagflation increases.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Power outage

- Energy conservation

- Energy market

- Embodied energy

- Energy industry

- Gasoline usage and pricing

- Peak coal

- Petroleum politics

- Resource-based view

- Social metabolism

References

[edit]- ^ Kumail Kazmi (4 September 2021). "Essay on Energy Crisis". Smadent. Archived from the original on 4 September 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- ^ F. William Engdahl (18 March 2012). "Behind Oil Price Rise: Peak Oil or Wall Street Speculation?". Axis of Logic. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- ^ Eenergiläget in Sweden 2012 figure 49000 and 53

- ^ "Kuwait says high oil price not justified". UpStreamOnline. Associated Press. 12 March 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- ^ "Coal shortage has China living on the edge". Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- ^ "China's Guangdong faces severe power shortage". Reuters. 6 March 2008. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- ^ "TABLE-China power shortage forecasts by region". Reuters. 2 June 2011. Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ "Mbeki in pledge on energy crisis". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 10 February 2008.

- ^ "Musharraf for emergency measures to overcome energy crisis". Associated Press of Pakistan. Archived from the original on 22 April 2007. Retrieved 10 February 2008.

- ^ "Pakistan's PM announces energy policy to tackle crisis". BBC. 22 April 2010. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- ^ Tollefson, Jeff (2008). "Energy crisis upsets platinum market". Nature. 451 (7181): 877. Bibcode:2008Natur.451..877T. doi:10.1038/451877a. PMID 18288152. S2CID 46240720.

- ^ "Israel cannot shirk its responsibility for Gaza's electricity crisis", B'Tselem, 16 January 2017

- ^ Palestinian Authority halts payments for Israeli electricity to Gaza: Israel, Reuters, 27 April 2017

- ^ Gaza's electricity crisis sheds light on gap between social classes, al-Monitor, March 2016

- ^ The humanitarian impact of Gaza's electricity and fuel crisis Archived 22 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine, UN OCHA, March 2014

- ^ "Covid is at the center of world's energy crunch, but a cascade of problems is fueling it". NBC News. 8 October 2021.

- ^ "Energy crisis: The blame game has begun - but are some of the claims just hot air?". Sky News. 22 September 2021.

- ^ "Don't Expect OPEC to Keep You Warm This Winter". Bloomberg. 17 October 2021.

- ^ Shirin Jaafari (22 November 2021). "Lebanon's electricity crisis means life under candlelight for some, profits for others".

- ^ "DOE Hirsch Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ Vittorio E. Pareto, Marcos P. Pareto (August 2008). "The Urban Component of the Energy Crisis". SSRN 1221622.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Super Fuel: Thorium, The Green Energy Source For The Future", Macmillan, 2012.

- ^ Bernanke, Ben S. (February 1983). "Irreversibility, Uncertainty, and Cyclical Investment" (PDF). The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 98 (1): 85–106. doi:10.2307/1885568. JSTOR 1885568. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 September 2014.

- ^ Hamilton, James D. (1988). "A Neoclassical Model of Unemployment and the Business Cycle". Journal of Political Economy. 96 (3): 593–617. doi:10.1086/261553. ISSN 0022-3808. JSTOR 1830361. S2CID 153422483.

- ^ Bernanke, Ben; Gertler, Mark; Watson, Mark (1997). "Systematic Monetary Policy and the Effects of Oil Price Shocks" (PDF). Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 28 (1): 91–157. doi:10.2307/2534702. JSTOR 2534702. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2017.

- ^ Bloomberg New Energy Finance, UNEP SEFI, Frankfurt School, Global Trends in Renewable Energy Investment 2011 Archived 13 January 2013 at archive.today

- ^ Bergin, Tom (30 January 2008). "High Oil Prices Boost Energy Efficiency - Report". www.planetark.org. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ^ Bank, European Investment (8 November 2022). EIB Investment Survey 2022 - EU overview. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5397-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Ammann, Daniel (2009). The King of Oil: The Secret Lives of Marc Rich. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-57074-3.

- The Power of Community: How Cuba Survived Peak Oil – examines the effect of cold war oil shortages during the Special Period.

- Resource Wars: The New Landscape of Global Conflict by Michael Klare

- Half Gone: Oil, Gas, Hot Air and the Global Energy Crisis by Jeremy Leggett

- The Long Emergency by James Howard Kunstler, explores a psychology of previous investment

- Eating Fossil Fuels by Dale Allen Pfeiffer

- The Coming Oil Crisis by Colin Campbell

- Energy and American Society: Thirteen Myths – disputes an energy crisis exists in 2007

- The Final Energy Crisis (2nd edition) ed by Sheila Newman (Pluto Press, London, 2008); a study of energy trends, prospects, assets and liabilities in different political systems and regions

- The End of Oil by Paul Roberts

- Sustainable energy - Without the Hot Air, David J.C. MacKay, 384 pages, UIT Cambridge (2009) ISBN 978-0954452933

- 2081: A Hopeful View of the Human Future, Gerard K. O'Neill, 284 pages, Simon & Schuster (1981) ISBN 978-0671242572

- The Nuclear Imperative: A Critical Look at the Approaching Energy Crisis (More Physics for Presidents), Jeff Eerkens, 212 pages, Springer (2010) ISBN 978-9048186662

- Rocks, Lawrence; Runyon, Richard P (1972). The Energy Crisis. Crown Publishers. ISBN 978-0-517-501641.

External links

[edit]