Chronology of the Crusades, 1187–1291

This chronology presents the timeline of the Crusades from the beginning of the Third Crusade, first called for, in 1187 to the fall of Acre in 1291. This is keyed towards the major events of the Crusades to the Holy Land, but also includes those of the Reconquista, the Popular Crusades and the Northern Crusades.[1]

Background

[edit]After the loss of Jerusalem in 1187, Saladin was in a position to drive the Franks out of the Holy Land. The pope responded by calling for a new crusade and Western Europe responded.[2]

1187

- 20 September – 2 October. Saladin's conquest over the Franks is nearly complete with his successful Siege of Jerusalem.[3]

- 20 October. Urban III dies and is succeeded by Gregory VIII on 25 October.[a][5]

- 29 October. Gregory VIII issues the bull Audita tremendi calling for the Third Crusade.[6]

- Shortly thereafter. Richard the Lionheart, then duke of Aquitaine, takes the cross with other nobles at Tours.[7]

- 12 November. Conrad of Montferrat leads the defense of the city against Saladin at the Siege of Tyre. The siege is abandoned on 1 January 1188.[8]

- 19 December. Clement III becomes pope after the death of Gregory VIII.[9]

- Late December. Saladin begins his Siege of Belvoir Castle.[10]

- (Date unknown). Chieftain Esbern the Resolute calls for Danish support of the Third Crusade.[11]

- (Date unknown). Canute I of Sweden repels a fleet of pagan Karelians ravaging coastal towns. He builds a defensive tower in Stockholm in response.[12]

Third Crusade

[edit]The Third Crusade was led by Frederick Barbarossa and Richard the Lionheart, and was followed shortly by the Crusade of 1197.[2]

1188

- January. Henry II of England and Philip II of France take the cross at Gisors.[13][14]

- 11 February. In order to finance the crusade, the Saladin tithe is begun in England.[15]

- 27 March. Frederick Barbarossa takes the cross at the Curia Christi held in Mainz.[16]

- Spring. Saladin releases Guy of Lusignan from captivity.[17]

- 26 May. Barbarossa sends Saladin an ultimatum to withdraw from the lands he had taken.[18]

- 20–22 July. Bohemond III of Antioch is defeated by Saladin at the Siege of Laodicea.[19]

- 26–29 July. Saladin defeats the Knights Hospitaller at the Siege of Sahyun Castle.[20]

- 5–9 August. The Principality of Antioch is defeated by the forces of Saladin at the Siege of al-Shughur.[21]

- 20–23 August. Shortly thereafter, Saladin successfully executes the Siege of Bourzey Castle.[21]

- November. The Franks abandon Kerak Castle to the Ayybuids after the Siege of Kerak.[22]

- Early November – 6 December. Saladin and his brother al-Adil I capture the Templar castle after the Siege of Safed.[23]

1189

- 9 January. After over a year, Saladin is successful in his Siege of Belvoir Castle.[10]

- 11 May. The Third Crusade begins, with Frederick Barbarossa and his forces departing Regensburg.[24]

- June. A Holy Roman Empire fleet, supported by Denmark and Flanders, en route to the Holy Land, stops in the Algarve and attack the castle there in the Alvor massacre.[25]

- 6 July. Henry II of England dies and is succeeded by his son Richard the Lionheart, who was crowned on 3 September and continued his father's plans for the crusade.[26]

- 21 July – 3 September. Sancho I of Portugal teams with Crusaders en route to the Holy Land defeat the Moors at the Siege of Silves.[27]

- August. Guy of Lusignan marches to Tyre but is refused entry by Conrad of Montferrat.

- 26 August. Barbarossa's forces seize the Byzantine city of Philippopolis.[28]

- 28 August. Guy of Lusignan begins the Siege of Acre.[29]

- 1 September. The Holy Roman Empire fleet arrives at Acre.[25]

- 11 November. William II of Sicily dies and the kingdom is seized by Tancred of Sicily.[30]

1190

- April. An English fleet under the command of Richard de Camville and Robert de Sablé departs Dartmouth to meet Richard the Lionheart in Marseille.[31]

- April. After a long siege, Muslim forces under Saladin capture Beaufort Castle from Reginald of Sidon.[32]

- Spring. A northern fleet fought a battle with the Moors and is defeated at the Strait of Gibraltar.[33]

- Spring. A Bulgarian force defeats the Byzantines at the Battle of Tryavna Pass.[34]

- 7 May. A Crusader army led by Frederick of Swabia and Berthold of Merania defeat the Seljuk Turks led by Kaykhusraw I at the Battle of Philomelion.[35]

- 18 May. Barbarossa led an army commanded by Frederick of Swabia, Děpolt II and Géza of Hungary to defeat the Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Iconium.[36]

- 10 June. Frederick Barbarossa drowns while crossing the Saleph River and his army returns to Germany.[16]

- Summer. An English ship separated from its fleet sails into Silves while the city was besieged by the Almohads and the English crusaders participated in the successful defense of the city.[33]

- 13–19 July. The Knights Templar under Gualdim Pais successfully repel the Moors at the Siege of Tomar.[37]

- 25 July. Sibylla of Jerusalem and her two daughters die and her sister Isabella I of Jerusalem becomes queen.[38]

- 7 August. Richard the Lionheart leaves for Sicily, arriving at Messina on 23 September. His fleet had arrived earlier, on 14 September.[39]

- 4 October. Richard the Lionheart captures Messina.[39] Tancred of Sicily agrees to a treaty in exchange for his recognition and the release of Joan of England.[40]

- Early November. The marriage of Isabella I of Jerusalem and Humphrey IV of Toron is annulled.[38]

- 24 November Isabella I of Jerusalem marries Conrad of Montferrat.[41]

1191

- 30 March. Celestine III becomes pope.[42]

- 10 April. Richard the Lionheart leaves Sicily. Bad weather forces him to land in Cyprus, entering Limassol on 6 May.[43]

- 15 April. Henry VI of Germany becomes Holy Roman Emperor.[44]

- 20 April. Philip II of France arrives at Acre.[43]

- 6 May. Bad weather forces the fleet of Richard the Lionheart to land at Limassol. The Conquest of Cyprus is complete by 1 June.[45]

- 12 May. Berengaria of Navarre marries Richard the Lionheart in Cyprus. She was the eldest daughter of Sancho VI of Navarre and Sancha of Castile.[46]

- 8 June. Richard the Lionheart arrives at Acre.[47]

- 12 July. Acre surrenders to the Crusaders, ending the two-year Siege of Acre.[47]

- 31 July. Philip II of France, accompanied by Conrad of Montferrat, departs to Tyre and returns to France. He leaves behind a French army under the command of Hugh III of Burgundy.[14]

- 20 August. Richard the Lionheart has the Muslim prisoners of war captured at Acre beheaded during the Massacre at Ayyadieh. In retaliation, Saladin does same to his Christian prisoners.[48]

- 7 September. Richard the Lionheart leads a Crusader army to defeat Saladin at the Battle of Arsuf.[49]

- November. The Crusader army advances on Jerusalem.[50]

- 12 December. Saladin disbands most of his army under pressure from his emirs.[51]

- (Date unknown). Canute VI leads a Danish Crusade to Finland.[52]

1192

- Before 24 April. Conrad of Montferrat (Conrad I of Jerusalem) is elected king of Jerusalem.[41]

- 28 April. Conrad of Montferrat is murdered by two Assassins.[53]

- 6 May. Henry II of Champagne marries Isabella I of Jerusalem, then pregnant with their child Maria of Montferrat. He becomes Henry I of Jerusalem.[38]

- 21 June. Enrico Dandolo becomes doge of Venice.[54]

- 8 August. In the final battle of the Third Crusade, Richard the Lionheart defeats Saladin at the Battle of Jaffa.[55]

- 2 September. Richard the Lionheart and Saladin agree to the Treaty of Jaffa. Jerusalem would remain under Muslim control, while allowing unarmed Christian pilgrims and traders to visit the city.[56]

- 9 October. Richard the Lionheart departs the Holy Land.[57]

- Before Christmas. Leopold V of Austria arrests Richard the Lionheart, accusing him of the murder of his cousin Conrad of Montferrat, holding him in captivity at Dürnstein Castle.[58]

- (Date unknown). The Teutonic Knights are recognized by Celestine III.[59]

- (Date unknown). English chronicler and monk Richard of Devizes writes hisChronicon de rebus gestis Ricardi Primi covering the reign of Richard I of England from 1189–1192.[60]

1193

- 4 March. Saladin dies and is succeeded by his sons Al-Aziz Uthman in Egypt and Al-Afdal in Syria.[61]

- 28 March. Richard the Lionheart turned over to Henry VI of Germany who imprisons him in Trifels Castle.[b]

- (Date unknown). Celestine III calls for a crusades in Spain and in Northern Europe.[63]

1194

- 4 February. Richard the Lionheart is ransomed and released from captivity.[58]

- 11 March. Forgiving his brother John of England for his revolt with Philip II of France during his captivity, Richard the Lionheart was crowned a second time and declares war on France.[64]

- Spring. Casimir II the Just organizes an expedition against the Baltic Yotvingians.[65]

- October. Leo I of Armenia invites Bohemond III of Antioch to Bagras to resolve their differences. Upon Bohemond's arrival, Leon captures him and his family, and takes them to the capital of Sis.[66]

- (Date unknown). The Bulgarians defeat the Byzantines at the Battle of Arcadiopolis.[67]

- (Date unknown). Raymond V of Toulouse, strong opponent of heresy, dies and his succeeded by his son Raymond VI of Toulouse who favored the Cathars.[68]

1195

- March. Henry VI of Germany announces a new crusade, later known at the Crusade of 1197.[44]

- 8 April. Alexios III Angelos becomes Byzantine emperor after deposing Isaac II Angelos.[69]

- 1 June. A Georgian force defeats the Ildenizids of Azerbaijan at the Battle of Shamkor.[70]

- 18 July. The Almohads led by caliph Yaqub al-Mansur attacked the Kingdom of Castile at the Battle of Alarcos.[71][72]

- Later. Alfonso IX of León invades Castile and is excommunicated by Celestine III.[73]

1196

- January. The Treaty of Louviers is signed by Philip II of France and Richard the Lionheart.[74]

- (Date unknown). Bulgarian forces under Ivan Asen I defeat the Byzantine army at the Battle of Serres.[75]

- (Date unknown). Norman poet and chronicler Ambroise of Evreux writes of the Third Crusade in his Old French poems L´Estoire de la guerre sainte and Itinerarium regis Ricardi.[76]

- (Date unknown). Ephraim of Bonn write his Emeḳ ha-Bacha concerning the treatment of Jews in Europe in the 12th century.[77]

1197

- March. The German forces under Henry VI of Germany begin the Crusade of 1197.[78]

- 10 September. Al-Adil I leads a force that takes the city in the Battle of Jaffa.[79]

- 10 September. Henry I of Jerusalem dies from falling out of a window at his palace in Acre. His widow, Isabella I of Jerusalem, becomes regent while the kingdom is thrown into consternation.[80]

- 22 September. The German forces of the Crusade of 1197 arrive at Acre.[81]

- 28 September. Henry VI of Germany dies of malaria at Messina, while preparing an expedition against the Byzantine usurper Alexios III Angelos.[44]

- 28 November. The German crusaders fail to take the city during the Siege of Toron, which lasts until 2 February 1198.[82]

- (Date unknown). Celestine III again calls for a crusade in Spain.[83]

- (Date unknown). Knights of the Order of Calatrava take Salvatierra Castle from the Moors, holding it until 1211.[84]

Fourth Crusade

[edit]The Fourth Crusade was launched to again go the Holy Land, but instead resulted in the Sack of Constantinople and the collapse of the Byzantine Empire. Shortly thereafter, the Albigensian Crusade against the Cathar heretics and the Children's Crusade began.[85]

1198

- 8 January. Innocent III becomes pope.[86]

- 2 February. Failing to take the city, the German crusaders lift the Siege of Toron and return home.[82]

- Spring. Aimery of Cyprus marries Isabella I of Jerusalem and are crowned as king and queen of Jerusalem at Acre.[87]

- July 1 Aimery of Cyprus signs a treaty with al-Adil I securing the Crusader possessions from Acre to as far as Antioch for five years and eight months.[87]

- 15 August. Innocent III issues the bull Post miserabile calling for the Fourth Crusade.[88]

- August. The Livonian Crusades begin with the Wars against Livs and Latgalians. Berthold of Hanover fails to defeat the Livonians and is killed.[89]

1199

- 6 April. Richard the Lionheart dies and his brother John of England becomes king.[90]

- 28 November. Due to the preaching of Fulk of Neuilly, a Crusade army is organized at a tournament held at Ecry-sur-Aisne by Theobald III of Champagne.[91][92]

- (Date unknown). Michael the Syrian writes his Chronicle in Syriac, covering history of the world down to 1196.[93]

1200

- 17 February. Al-Adil I proclaims himself sultan of Egypt.[94]

- (Date unknown). Albert of Buxhoeveden, bishop of Riga, leads a crusade to conquer Latvia.[95]

- (Date unknown). The Livre au Roi, the earliest surviving text of the Assizes of Jerusalem, is written.[96]

1201

- March. Envoys are sent to Venice, then led by doge Enrico Dandolo, to negotiate sea transportation of the crusaders to Cairo, believed to be the best route to secure Jerusalem.[97]

- 24 May. Theobald III of Champagne dies and is replaced by Boniface of Montferrat as leader of the crusade that summer.[98]

- (Date unknown). Alexios IV Angelos, son of Isaac II Angelos, takes refuge in Germany with his brother-in-law Philip of Swabia. He begins to get backing to be placed as Byzantine emperor.[99]

1202

- May. The Crusader force gathers in Venice, but in smaller numbers that expected. Unable to pay the Venetians for the boats they built, Enrico Dandolo proposes an attack on Adriatic ports as payment.[c][100]

- Spring. Crusaders who chose to continue to the Holy Land arrive in Acre.[101]

- Later. As part of the War of the Antiochene Succession, Leo I of Armenia attacks Antioch, defended by recently arrived Crusaders. Renard of Dampierre is captured, to be held prisoner until 1233.[102]

- 10–24 November. The Crusaders and Venetians sack the city after the Siege of Zara.[103]

- Later. Innocent III excommunicates those who attacked Zara and orders them to proceed to Jerusalem. The excommunication is lifted for non-Venetians in February 1203.[104]

- Winter. Boniface of Montferrat meets with Alexios IV Angelos who offers to provide resources to the crusade in exchange for being placed as Byzantine emperor.[99]

- (Date unknown). Anders Sunesen leads a crusade against the Finns as part of the Danish Crusade.[105]

- (Date unknown). The Livonian Brothers of the Sword is established.[106]

1203

- April. The Crusaders depart for Constantinople.[107]

- 11 July – 1 August. The Crusaders are victorious after the Siege of Constantinople.[108]

- 19 July. Isaac II Angelos and Alexios IV Angelos become co-emperors of Byzantium.[109]

- Late August. Crusade leadership writes to Innocent III explaining their actions and vowing to proceed to Egypt in the spring.[110]

1204

- 27 January. Nicholas Kanabos is proclaimed as rival Byzantine emperor. Isaac II Angelos dies shortly thereafter.[99]

- 8 February. Alexios IV Angelos is murdered and Nicholas Kanabos is imprisoned. Alexios V Doukas becomes emperor.[111]

- 12–15 April. The Crusaders and Venetians participate in the Sack of Constantinople, essentially ending the Byzantine empire. The new Latin Empire was created under Baldwin IX of Flanders, as Baldwin I.[112]

- May. Alexios I of Trebizond establishes the Empire of Trebizond with the backing of Tamar of Georgia.[113]

- September–October. The Byzantine empire is formally partitioned with the signing of the Partitio terrarum imperii Romaniae, creating the Frankokratia.[114]

- September. Realizing that the Fourth Crusade will not bring sufficient reinforcements to Acre, Aimery of Cyprus negotiates a six-year truce with al-Adil I.[115]

- December. Alexios V Doukas is captured by Thierry de Loos and executed by being thrown from the Column of Theodosios in Constantinople.[111]

- Late. Innocent III authorizes those who took a crusading vow but could not go may crusade in the Baltic instead.[116]

1205

- Early. Theodore I Laskaris founds the Empire of Nicaea.[117]

- 18 March. Nicaea defeats the Latins at the Battle of Adramyttion, the first battle of the Nicaean–Latin wars.[118]

- 1 April. Aimery of Cyprus dies and is succeeded by Hugh I of Cyprus. Isabella I of Jerusalem is the sole ruler of Jerusalem.[119]

- 14 April. The Bulgarians are successful in the Battle of Adrianople, the first of the Bulgarian–Latin wars. This if followed by a similar victory at the Battle of Serres in June.[120]

- April. Isabella I of Jerusalem dies and is succeeded as queen of Jerusalem by her daughter Maria of Montferrat.[121]

- Summer. The Franks defeat the remaining Byzantines at the Battle of the Olive Grove of Kountouras completing their conquest of the Morea. The Principality of Achaea is founded shortly thereafter.[122]

- (Date unknown). The Seljuk Turks led by Kaykhusraw I fail in their first Siege of Trebizond with the defenses of the city led by Alexios I of Trebizond, emperor and claimant to the Byzantine throne.[123]

- (Date unknown). Othon de la Roche founds the Duchy of Athens.[124]

- (Date unknown). German monk Gunther of Pairis writes his Historia Constantinopolitana about the Fourth Crusade.[125]

1206

- 31 January. Bulgarian forces under Kaloyan, defeat the remnants of the Latin army at the Battle of Rusion.[120]

- February. The Bulgarians attack and loot the fortified town after the Battle of Rodosto, defended by a Venetian garrison.[120]

- July. Baldwin I, Latin Emperor, captive since the Battle of Adrianople, dies at Baldwin's Tower and is succeeded by Henry of Flanders who is crowned on 20 August.[126]

- Late. Saint Dominic and Diego de Acebo establish the Monastery of Our Lady of Prouille which embraced Albigensianism.[d][127]

- (Date unknown). Byzantine historian Niketas Choniates writes Nicetæ Choniatæ Historia, covering the period 1118–1207.[128]

1207

- 2 February. Terra Mariana (Old Livonia) is established as a vassal state of the Holy See.[129]

- March. The Seljuk Turks are successful at the Siege of Antalya.[130]

- May. Raymond VI of Toulouse is excommunicated for not dealing with the Cathars.[68]

- 4 September. The Bulgarians defeat the Latins at the Battle of Messinopolis. Latin commander Boniface of Montferrat is killed.[120]

1208

- 13 January. Senior papal legate Pierre de Castelnau meets with Raymond VI of Toulouse over the Cathar issue and is murdered the next day.[131]

- March. Innocent III calls for the Albigensian Crusade against the Cathars.[132]

- Early June. The Bulgarians defeat the Latins at the Battle of Beroia.[120]

- 30 June. The Latin Empire defeats the Bulgarians at the Battle of Philippopolis.[133]

1209

- July. The Albigensian Crusade against the Cathars begins under the command of Arnaud Amalric.[68]

- 22 July. The Crusaders conduct the Massacre at Béziers.[e][134]

- 15 August. Cathar stronghold Carcassonne falls to the Crusaders.[132]

- Later. Simon de Montfort given control of the conquered territories of Béziers and Carcassonne and takes command of the Crusade.[68]

- (Date unknown). At the Council of Avignon, Raymond VI of Toulouse and the inhabitants of Toulouse are excommunicated for failing to expel the Cathars.[68]

1210

- Early June – 22 July. Simon de Montfort and Arnaud Amalric defeat the Cathars at the Siege of Minerve.[132]

- 3 October. John of Brienne is crowned king of Jerusalem by virtue of his marriage to Maria of Montferrat.[135]

- (Date unknown). The forces of Peter II of Aragon defeat the defending Moorish forces at the Siege of al-Dāmūs.[136]

1211

- April. Simon de Montfort lays siege to Lavaur, destroying the city and its inhabitants.[68]

- 17 June. The Nicean forces of Theodore I Laskaris defeat the Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Antioch on the Meander. Kaykhusraw I, was killed on the field of battle and Alexios III Angelos was taken prisoner.[137]

- 15 October. Latin forces under Henry of Flanders defeat the Niceans led by Theodore I Laskaris at the Battle of the Rhyndacus.[138]

1212

- Early. Simon de Montfort takes Toulouse, causing his brother-in-law Peter II of Aragon to intervene later in the year.[68]

- Early Spring. The Children's Crusade begins with disastrous results.[139]

- 16 July. Alfonso VIII of Castile, Sancho VII of Navarre and Peter II of Aragon defeat the Moorish forces under Muhammad al-Nasir at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa.[140]

- (Date unknown). Isabella II of Jerusalem becomes queen of Jerusalem after the death of her mother Maria of Montferrat.[141]

- (Date unknown). Pope Innocent III calls for a crusade in Spain.[83]

- (Date unknown). Benedictine monk and chronicler Arnold of Lübeck writes Duellum Nicænum, a continuation of Helmold's Chronica Sclavorum.[142]

- (Date unknown). German knight and poet Wolfram von Eschenbach writes Willehalm, a tale involving Saracens.[143]

Fifth Crusade

[edit]The Fifth Crusade attacked Egypt with disastrous results.[144]

1213

- 18 January. Tamar of Georgia dies and is succeeded by her son George IV of Georgia.[145]

- 19 April. Innocent III issues his papal bull Quia maior calling for what will become the Fifth Crusade.[146][147]

- 12 September. Peter II of Aragon dies fighting his brother-in-law Simon de Montfort in the Battle of Muret, the last major battle of the Languedoc phase of the Albigensian Crusade.[148]

- (Date unknown). French knight and historian Geoffrey of Villehardouin writes his chronicle De la Conquête de Constantinople (On the Conquest of Constantinople) on the Fourth Crusade based on his experiences in the endeavor.[149]

- (Date unknown). Cistercian monk Peter of Vaux-de-Cernay writes his chronicle Historia Albigensis about the Albigensian Crusade, a primary source of that endeavor.[150]

1214

- 1 November. The Seljuk Turks under Kaykaus I defeat the Empire of Trebizond at the Siege of Sinope. Alexios I of Trebizond is taken prisoner.[151]

- December. After the Battle of the Rhyndacus, the Treaty of Nymphaeum is signed between the Latin Empire and the Empire of Nicaea.[138]

1215

- 8 January. Simon de Montfort is elected lord of Languedoc after his campaign against the Cathar heretics during the Albigensian Crusade.[152]

- Summer. Frederick II becomes king of Germany after the excommunication and abdication of Otto IV, taking the cross for the first time.[153]

- 24 August. Raymond VI of Toulouse captures Beaucaire, the first heretic victory in the Albigensian Crusade.[154]

- 11 November. The Fourth Lateran Council endorses the Fifth Crusade.[83]

1216

- 14 February. Leo I of Armenia reconquers the Principality of Antioch and Raymond-Roupen is installed as prince.[155]

- 18 July. Honorius III becomes pope, continuing the support of the new crusade.[156]

- (Date unknown). French knight Robert de Clari writes La Conquête de Constantinople, covering the period 1202–1205.[157]

1217

- 1 July. Forces depart France on the Fifth Crusade.[158]

- 30 July – 18 October. Portugal and the Crusaders under Soeiro II of Lisbon and William I of Holland defeat the Moors at the Siege of Alcácer do Sal, the first engagment of the Fifth Crusade.[159]

- 23 August. The forces of Andrew II of Hungary depart from Split for Syria on what is known as the Crusade of Andrew II of Hungary (Hungarian Crusade), part of the Fifth Crusade.[160]

- 21 September. The Livonian Brothers of the Sword defeat the Estonians at the Battle of St. Matthew's Day.[161]

- 22 September. Simon de Montfort begins the Siege of Toulouse, to put down the Languedoc revolt of the Albigensian Crusade.[162]

- 30 November – 7 December. The army of Andrew II of Hungary fails in their Siege of Mount Tabor against the fortress held by the Ayyubids.[160]

- 15 December. The Hungarian Crusade ends with their defeat at the Battle of Machghara by the Ayyubids.[160]

1218

- 10 January. Hugh I of Cyprus dies and is succeeded in Cyprus by his one-year old son Henry I of Cyprus.[163]

- March. Honorius III authorizes the Prussian Crusade.[164]

- 27 May. The first of the Crusader ships arrive in Egypt. Led by John of Brienne, other commanders include Leopold VI of Austria, Simon III of Sarrebrück, and masters Peire de Montagut, Hermann of Salza and Guérin de Montaigu.[165]

- 29 May. The Siege of Damietta begins.[166]

- 25 June. Simon de Montfort dies at the Siege of Toulouse. His son Amaury de Montfort continues the Albigensian Crusade with little success.[152]

- 1 August. Honorius III proclaims a new Albigensian Crusade.[167]

- 24 August. The siege engines of Oliver of Paderborn breach the main tower of Damietta which is taken is taken the next day.[166]

- 31 August. Al-Adil I dies and Al-Kamil becomes Ayyubid sultan of Egypt.[168]

- 9 November. Papal delegate Pelagius Galvani arrives in Egypt and takes command of the Crusade from John of Brienne.[169]

1219

- Early. Valdemar II of Denmark invades Estonia, which is elevated to a crusade by Honorius III, and takes Tallinn (Revel).[170]

- May. Leopold VI of Austria returns home from the Fifth Crusade.[171]

- 19 June. The forces of Valdemar II of Denmark defeat the Estonians at the Battle of Lyndanisse.[172]

- 29 August. After his overtures of peace were rejected, al-Kamil defeats the Crusaders under Pelagius Galvani and John of Brienne at the Battle of Fariskur.[173]

- September. Saint Francis of Assisi arrives in Egypt to negotiate with the sultan.[174]

- 5 November. The Crusaders take the city from the Ayyubids after the successful Siege of Damietta.[166]

1220

- Summer. An Egyptian fleet attacks a crusader fleet at Limassol, resulting in over a thousand casualties. The sea lanes had been left unguarded by Pelagius.[175]

- 8 August. The Estonians defeat the invading Swedes at the Battle of Lihula, ending their aggression for centuries.[176]

- 22 November. Frederick II and Constance of Aragon are crowned Holy Roman Emperor and Empress by Honorius III, taking the cross for the second time.[153]

- (Date unknown). Cardinal Oliver of Paderborn writes his Historia Damiatina, reflecting his experience in the Fifth Crusade.[177]

1221

- 26–28 August. In the final battle of the Fifth Crusade, the Crusader forces under Pelagius Galvani and John of Brienne are defeated by the Ayyubid forces of al-Kamil at the Battle of Mansurah.[178]

- 8 September. Pelagius Galvani surrenders and the Crusaders begin to depart Egypt. The Fifth Crusade has ended with nothing gained by the West.[179]

- (Date unknown). A Kievan Rus' force fails to defeat the Seljuk Turks under Kayqubad I at the Battle of Sudak.[180]

- (Date unknown). An Estonian force fails to take the city from the Danes in the Siege of Tallinn.[181]

1222

- September. The Mongols are successful at the Battle of Khunan, beginning the Mongol Invasions of Georgia.[182]

- (Date unknown). The Seljuk Turks fail in their second Siege of Trebizond.[180]

Sixth Crusade

[edit]Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, undertook the Sixth Crusade and made significant gains with no military actions.[183]

1223

- 23 March. In a meeting between Honorius III and Frederick II and John of Brienne, preparations begin for the Sixth Crusade to recapture Jerusalem. Frederick agrees to lead the Crusade and again takes the cross.[184]

- 14 July. Louis VIII of France becomes king after the death of his father Philip II of France.[185]

- (Date unknown). The Niceans defeat the Latins at the Battle of Poimanenon.[186]

1224

- (Date unknown). Amaury de Montfort cedes his titles and lands in Languedoc to Louis VIII of France.[187]

- (Date unknown). English chronicler Ralph of Coggeshall writes his Chronicon Anglicanum on the Fourth Crusade.[188]

1225

- 9 November. Frederick II marries Isabella II of Jerusalem, becoming king of Jerusalem.[189]

- (Date unknown). At the first Siege of Jaén, the forces of the Taifa of Jayyān defeat the forces of Ferdinand III of Castile.[190]

- (Date unknown). Icelandic historian Snorri Sturluson writes his Heimskringla concerning Scandinavian involvement in the Northern Crusades.[191]

1226

- 10 June – 9 September. Louis VIII of France is successful in his Siege of Avignon as part of the Royal intervention phase of the Albigensian Crusade.[192]

- 8 November. Louis IX of France becomes king after the death of his father Louis VIII of France.[193]

- (Date unknown). The Teutonic Knights undertake a new Crusade to subdue the pagan Prussians.[59]

- (Date unknown). French historian Jacques de Vitry writes his Historia Hierosolymitana on the Holy Land from the advent of Islam until the Fifth Crusade.[194]

1227

- January. The Livonian Brothers of the Sword and their allies defeat the last Estonian strongholds in the Battle of Muhu.[181]

- 19 March. Gregory IX becomes pope.[195]

- 22 July. Holstein forces defeat Valdemar II of Denmark and Otto the Child at the Battle of Bornhöved.[170]

- 8 September. The forces of the Sixth Crusade depart Europe. Shortly thereafter, Frederick II is forced to return due to illness. The rest of the army, now under the command of Henry of Limburg and Gérold of Lausanne.[196]

- 29 September. Gregory IX excommunicates Frederick II for his failure to fulfil his crusading vows.[196]

- 11 November. After the death of his brother al-Muazzam Isa, al-Kamil takes control of Jerusalem. His brother al-Ashraf Musa maintains control of Syria.[197]

- (Date unknown). Henry of Latvia writes his Livonian Chronicle.[176]

1228

- 4 May. Conrad II of Jerusalem becomes king of Jerusalem upon the death of his mother Isabella II of Jerusalem.

- 28 June. Gregory IX resinds his excommunication of Frederick II.[196]

- 7 September. Frederick II arrives at Acre. He sends Thomas of Accera and Balian Grenier to negotiate with the sultan al-Kamil.[198]

- (Date unknown). Ibn Hud seizes power over much of al-Andalus.[199]

- (Date unknown). Willibrand of Oldenburg leads the Drenther Crusade against the residents of Drenthe, lasting until 1232.[200]

1229

- 13 February. Gregory IX issues a papal bull calling for a new crusade in Spain.[201]

- 18 February. The Sixth Crusade end with the signing of the Treaty of Jaffa between Frederick II and al-Kamil. Jerusalem is restored to Christian rule.[202]

- 17 March. Frederick II enters Jerusalem and crowns himself king. He departs eight days later.[203]

- 12 April. Louis IX of France and Raymond VII of Toulouse sign the Treaty of Paris ending the Albigensian Crusade.[204]

- 5 September. James I of Aragon begins the Conquest of Majorca resulting in the creation of the Kingdom of Majorca.[205]

- 12 September. The Aragonese win the first engagement at Majorca at the Battle of Portopí.[205]

- (Date unknown). The Council of Toulouse entrusts the Inquisition to deal with the surviving heretics remaining from the Albigensian Crusade.[206]

- (Date unknown). The Chronicle of Ernoul is written.[207]

1230

- 9 March. Bulgaria defeats Thessalonica at the Battle of Klokotnitsa.[208]

- 24 June. The forces of Ferdinand III of Castile and García Fernández de Villamayor fail in their second Siege of Jaén.[209]

- 10–12 August. The Seljuks and Ayyubids defeat the Khwarazmians at the Battle of Yassıçemen.[210]

- October. The Teutonic Knights occupy Chelmno Land and begin their conquest of Prussia as authorized by Gregory IX.[211]

- 30 October. The Conquest of Majorca is completed.[205]

- (Date unknown). Berber historian Ibn Hammad writes his Akhbar muluk bani Ubayd wa-siratuhum about the Fatimids.[212]

1231

- Autumn. John of Brienne is crowned Latin Emperor.[135]

- (Date unknown). The crusade of Ferdinand III of Castile begins.[213]

- (Date unknown). The forces of Ferdinand III of Castile led by Alfonso de Molina and Álvaro Pérez de Castro defeat those of Ibn Hud at the Battle of Jerez, leading to the rise of Muhammad I of Granada.[214]

1232

- 15 June. Forces loyal to Henry I of Cyprus defeat those of Richard Filangieri at the Battle of Agridi.[215]

- 13 July. The Nasrid dynasty begins ruling the Emirate of Granada under Muhammad I of Granada, the first sultan of Granada.[216]

- (Date unknown). James I of Aragon begins his campaign against the Moors occupying Valencia.[213]

1233

- May–July. As part of his Valencian campaign, James I of Aragon and Bernat Guillem d'Entença defeat Zayyan ibn Mardanish at the Siege of Burriana.[217][218]

- (Date unknown). The papal attacks on heretics in the Stedinger Crusade is finally successful in 1234.[219]

- (Date unknown). Arab historian Ali ibn al-Athir writes his Complete Work of History.[220]

Barons' Crusade

[edit]After the truce that ended the Sixth Crusade, a further military action known as the Barons' Crusade was launched by Theobald I of Navarre and Richard of Cornwall, returning the Kingdom of Jerusalem to its largest extent since 1187.[221]

1234

- 7 April. Theobald I of Navarre becomes king.[222]

- 17 November. Gregory IX issues the papal bull Rachel suum videns calling for a new crusade to the Holy Land. This would result in the Barons' Crusade to begin in 1239.[223]

1235

- (Date unknown). An inconclusive Siege of Constantinople was launched by John III Doukas Vatatzes of Nicaea and Ivan Asen II of Bulgaria against the city defended by John of Brienne.[224]

- (Date unknown). Hungarian prince Coloman fails to quell the heretics during the Bosnian Crusade.[225]

1236

- 29 June. Ferdinand III of Castile captures Córdoba from Ibn Hud after the Siege of Córdoba, regaining the city held by the Moors since 711.[226]

- 22 September. Pagan troops of Samogitians and Semigallians defeat the Livonian Brothers of the Sword at Battle of Saule.[227]

1237

- 22 March. John of Brienne dies and is succeeded by Baldwin II, Latin Emperor.[135]

- 15 August. James I of Aragon and Bernat Guillem d'Entença defeat Zayyan ibn Mardanish at the Battle of the Puig, completing their Valencian campaign.[218]

1238

- Spring. The Portuguese conquest of the Algarve begins.[228]

- (Date unknown). The Taifa of Valencia becomes part of Aragon.[218]

- (Date unknown). Ibn Hud is assassinated.[199]

1239

- 2 November. Theobald I of Navarre initiates the Barons' Crusade after the expiration of the ten-year treaty between the West and the Ayyubids.[229]

- 13 November. The army of Theobald I of Navarre is defeated by the Ayyubids at the Battle at Gaza.[230]

- 3 December. Theobald I of Navarre departs the Holy Land. Four days later, Damascene emir an-Nasir Dawud captures Jerusalem from the Franks but does not hold it.[230]

Red: Crusader states in 1239; Pink: territory acquired in 1239–1241

1240

- 8 October. The English forces of Richard of Cornwall arrive in the Holy Land.[231]

- 15 July. In the beginning of the Swedish–Novgorodian Wars, the Novgorods defeats the Kingdom of Sweden at the Battle of the Neva.[232]

- (Date unknown). The Teutonic Knights of the Livonian Order are unsuccessful in their Livonian campaign against Rus'.[233]

1241

- 13 February. In the first Mongol invasion of Poland, the Mongols conduct their Sack of Sandomierz.[234]

- March. The First Mongol invasion of Hungary is successful.[235]

- 9 April. The Battle of Legnica completes the Mongol invasion of Poland.[236]

- 23 April. Richard of Cornwall completes the negotiation of the treaty with Al-Salih Ismail.[221]

- 3 May. The forces of Richard of Cornwall depart Acre, ending the Barons' Crusade.[229]

- May–June.The fleet of the Republic of Venice defeats that of the Empire of Nicaea at the Battle of Constantinople. [237]

- August. The first of the Danish Campaigns to Novgorod is inconclusive.[238]

1242

- 12 April. The forces of the Republic of Novgorod led by Alexander Nevsky defeat the forces of the Livonian Order at the Battle on the Ice. As a result, the Teutonic Order dropped all territorial claims over Russian lands[239]

- 28 May. During the Royal intervention phase of the Albigensian Crusade, a group of Cathars killed a group of inquisitors at the Avignonet massacre..[240]

- (Date unknown). Aleppan historian Kamal al-Din writes his Chronicle of Aleppo.[241]

1243

- May. The royal forces of Louis IX of France defeat the Cathars at the Siege of Montségur.[240]

- 25 June. Innocent IV becomes pope.[242]

- 23 September. Innocent IV issues the papal bull Qui iustis causis authorizing crusades in Prussia and Livonia.[242]

1244

- 22 May. The Moors surrender Xativa Castle to James I of Aragon following a five-month siege. The terms of surrender of the Moors were laid out in the subsequent Treaty of Xàtiva.[243]

- 11 July – 23 August. The Khwarazmians destroy the city and its inhabitants after their successful Siege of Jerusalem.[244]

- 17–18 October. The Ayyubid army as-Salih Ayyub, reinforced with Khwarezmian mercenaries, defeat the Franksh forces at the Battle of Forbie.[245]

- Late. After a near-fatal illness, Louis IX of France takes the cross (prior to papal authorization of a crusade).[193]

Seventh Crusade

[edit]Louis IX of France launched the Seventh Crusade against Egypt, again resulting in disaster.[246]

1245

- 28 June. At the First Council of Lyon, the Seventh Crusade to the Holy Land under Louis IX of France is authorized.[247]

- October. Jean de Joinville joins the Crusade.[248]

1246

- 28 February. Kingdom of Castile and the Order of Santiago commanded by Ferdinand III of Castile and Grand Master Pelayo Pérez Correa defeat a defending force of the Taifa of Jaén and the Emirate of Granada under Muhammad I of Granada at the Third Siege of Jaén.[249]

- March. Muhammad I enters into peace agreement with Castile and Granada becomes its vassal.[250]

- 15 April. James I of Aragon and his son-in-law Alfonso X of Castile enter into the Al-Azraq Treaty of 1245 with Moorish commander al-Azraq.[251]

- August. As an embassy of Innocent IV, Franciscan John of Plano Carpini travels to Mongolia to meet with Güyük Khan who demands that the pope pay him homage. Upon his return at the end of 1247, John reports to Rome that the Mongols were only out for conquest.[252]

1247

- May. Dominican Ascelin of Lombardy is sent to meet the Mongol general Baiju Noyan. Baiju and Ascelin discussed an alliance against the Ayyubids.[253]

- July. Castile begins the 16-month Siege of Seville.[254]

- August – 15 October. The Ayyubids defeat the Hospitallers at the Siege of Ascalon and occupy the city.[255]

1248

- 25 August. The Seventh Crusade begins when Louis IX of France leaves Paris with his queen Margaret of Provence, her sister Beatrice of Provence and two of Louis' brothers, Charles I of Anjou and Robert I of Artois.[256]

- 28 November. Ferdinand III of Castile, supported by Ramón de Bonifaz, defeats the Moors led by Axataf after the 16-month Siege of Seville.[254][257]

1249

- March. Afonso III of Portugal and Paio Peres Correia capture the Algarve from the Taifa of Niebla after the Siege of Faro.[258] This marked the end of the Portuguese conquest of the Algarve and therefore their Reconquista efforts in the Iberian peninsula.[228]

- 6 June. The Crusades capture the Egyptian city after the successful Siege of Damietta.[259]

- 22 November. Ayyubid sultan as-Salih Ayyub dies and is succeeded by his son Turanshah.[260]

- Approximate. The Tavastians are defeated in the Second Swedish Crusade.[261]

1250

- 8–11 February. Louis IX of France and his forces are defeated by the Ayyubids at the Battle of Mansurah (1250).[262]

- 6 April. In the last major battle of the Seventh Crusade, the Franks are totally defeated by the Ayyubids at the Battle of Fariskur. Louis IX of France and much of his force is captured.[263]

- 2 May. Turanshah is murdered by a group of Mamluks led by Baibars. He is succeeded by his father's widow Shajar al-Durr, marking the end of the Ayyubid dynasty.[264]

- 6 May. Louis IX of France is freed and later goes to Acre where he works to free his captive force. He finally returns home in 1254.[246]

- 31 July. Aybak becomes the first Mamluk sultan and later marries Shajar al-Durr.[264]

- 13 December. Frederick II dies and the Holy Roman Empire enters the Great Interregnum.[153]

1251

- 2 February. The Mamluks of Egypt defeat the Ayyubids of Syria at the Battle of al-Kura.[265]

- (Date unknown). A popular crusade known as the Shepherds' Crusade is formed to free Louis IX of France from captivity. The crusade does not advance out of France.[266]

- (Date unknown). Cistercian monk Alberic of Trois-Fontaines writes his Chronicle.[267]

1252

- 15 May. Innocent IV issues the papal bull Ad exstirpanda, which authorizes the torture of heretics in the Inquisition.[268]

- (Date unknown). Italian historian Philip of Novara writes his History of the War between the Emperor Frederick and Sir John of Ibelin. This was included in Les Gestes des Chiprois.[269][270]

1253

- 8 July. Theobald II of Navarre becomes king.[271]

1254

- 24 April. Louis IX of France departs from Acre, ending the Seventh Crusade.[246]

- 21 May. Conradin becomes the nominal king of Jerusalem upon the death of Conrad II of Jerusalem.[272]

1256

- 15 December. Mongol forces under Hulagu Khan end their campaign against the Assassins and Abbasid Caliphate, begun in the Spring, with the capture of Alamut Castle.[273]

1257

- (Date unknown). Arab historian Ibn al-Jawzi writes his Al-Muntadham fi tarikh al-muluk wa-'l-umam (History of the caliph and the nation).[274]

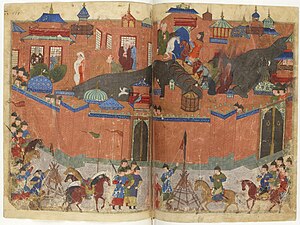

1258

- 10 February. The Mongols under Hulegu attack the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate and are successful if their Siege of Baghdad. Caliph al-Musta'sim is killed 10 days later and the caliphate goes into decline.[275]

1259

- Summer/Fall. The Empire of Nicaea is successful against the Despotate of Epirus, Kingdom of Sicily and Principality of Achaea in the Battle of Pelagonia.[276]

- Late. The Second Mongol invasion of Poland is successful.[277]

- (Date unknown). English chronicler Matthew Paris writes his Chronica Majora, presenting a universal history from Creation until 1259.[278]

1260

- 18–24 January. Mongol leader Hulagu Khan, supported by forces of Bohemond VI of Antioch and Hethum I of Armenia, conquer the city in their Siege of Aleppo.[279]

- January–August. The Latin Empire defeats an attempt by the Empire of Nicaea to conquer the city in the Siege of Constantinople.[280]

- 3 September. The Mamluks defeat the Mongols at the Battle of Ain Jalut.[281]

- 10–23 September. After the Battle of Salé, a Castilian fleet sent by Alfonso X of Castile temporarily occupies Salé in Morocco.[282]

- 24 October. Baybars becomes Mamluk sultan of Egypt.[283]

- (Date unknown). Persian historian Ata-Malik Juvayni writes his Tarīkh-i Jahān-gushā (History of the World Conqueror), an account of the Mongol Empire.[284]

1261

- 24 July. The Empire of Nicaea is successful in their Reconquest of Constantinople, ousting the Latin Empire and restoring the Byzantine Empire.[280]

- 15 August 1261. Michael VIII Palaiologos begins the Palaiologan dynasty to rule the Byzantine Empire until 1453.[285]

- 29 August. Urban IV becomes pope.[286]

- 25 November. After the 11-month Siege of Jerez, the Moorish enclave of Jerez de la Frontera is incorporated into the Crown of Castile.[287]

1263

- (Date unknown). The Principality of Achaea defeats the Byzantines at the Battle of Prinitza.[288]

- (Date unknown). The Achaea again defeats the Byzantines at the Battle of Makryplagi.[280]

1265

- 5 February. Clement IV become pope.[289]

- 8 February. Abaqa becomes second to rule the Mongol Ilkhanate, after the death of his father Hulagu Khan.[290]

- 21 March – 29 April. The Mamluks under Baibars defeat the Knights Hospitaller in battle, resulting in the Fall of Arsuf.[291]

- October. James I of Aragon begins the Conquest of Murcia, taking the Muslim-held Taifa of Murcia on behalf of his ally Alfonso X of Castile. He is supported by Manuel of Castile and Paio Peres Correia.[292]

- Fall–Winter. Clement IV issues a general Crusade bull for the whole of Spain, when the kings of Aragon and Castile joined in the expedition against the Taifa of Murcia.[293]

- (Date unknown). Baibars destroys the city of Caesarea Maritima.[294]

Eighth Crusade

[edit]Louis IX of France again takes the cross, launching Eighth Crusade against Tunis. His death marked the end of the crusade.[246]

1266

- 5 January 1266. Charles I of Anjou and Beatrice of Provence crowned king and queen of Sicily.[295]

- Mid-January. Clement IV calls for a new expedition to the Holy Land which will become the Eighth Crusade.[296]

- 31 January. Murcia surrenders to James I of Aragon.[292]

- 13 June – 23 July. Baibars destroys the contingent of Knights Templar at the Siege of Safed.[297]

- 24 August. Baibars conquers Cilician Armenia at the Battle of Mari.[298]

1267

- 2 March. German knights depart on the Crusade of 1267 in response to the papal bull Expansis in cruce issued in August 1265. The crusade accomplished nothing.[299]

- 24 March. Louis IX of France takes the cross to go on the Eighth Crusade.[300]

1268

- 18 February. The combined forces of Danish Estonia and the Livonian Order engage the forces of Novgorod and Pskov at the inconclusive Battle of Wesenberg.[301]

- May. Baibars is successful in his Siege of Antioch.[302]

- 29 October. Conradin is beheaded on orders of Charles I of Anjou. and is succeeded by Hugh III of Cyprus as king of Cyprus and Jerusalem.[303]

1269

- 1 September. Fernando Sánchez de Castro and Pedro Fernández de Híjar begin the Crusade of the Infants of Aragon, abandoning it the next year with no results.[304]

- 24 September 1269. Hugh III of Cyprus is crowned king of Jerusalem. The claim of Maria of Antioch to the throne is rejected.[305]

1270

- 1 July. The Eighth Crusade begins as the forces of Louis IX of France depart for Tunis.[306]

- 17 August. Philip of Montfort killed by Assassins on the orders of Baibars.[307]

- 25 August. Louis IX of France dies while on the Eighth Crusade and succeeded by his son Philip III of France.[308]

- 20 October. Lord Edward and his forces depart for Tunis. They will arrive too late for the Eighth Crusade and proceed to the Holy Land.[309]

- 21 October. Hethum I of Armenia abdicates and is succeeded by his son Leo II of Armenia.[310]

- 1 November. The Treaty of Tunis is signed, ending the Eighth Crusade. Philip III of France, Charles I of Anjou and Theobald II of Navarre signed for the Latin Christians and sultan Muhammad I al-Mustansir for Tunis.[311]

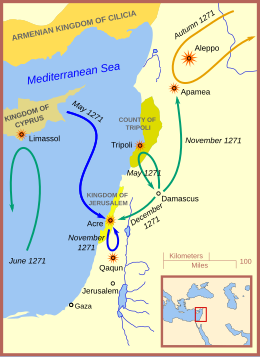

Lord Edward's Crusade

[edit]English forces en route to the Eighth Crusade arrived too late and launched Lord Edward's Crusade in the Holy Land, the last major Western offensive there.[312]

Mamluks Crusaders Mongols

1270

- 18 November. Lord Edward and his forces arrive in Sardinia.[309]

1271

- Winter–Spring. Baibars besieges Safita in February, then takes Krak des Chevaliers, Gibelacar and Tripoli.[313]

- 13 March – 8 April. Baibars captures the Hospitaller stonghold with the Fall of Krak des Chevaliers.[314]

- 9 May. Lord Edward and his forces arrive in Acre.[315]

- Late May. Baibars offers Bohemond VI of Antioch a ten-year truce after the Siege of Tripoli.[316]

- 1 September. Gregory X is elected pope and preaches new crusade in coordination with the Mongols.[317]

- (Date unknown). The Gran conquista de Ultramar, a late 13th-century Castilian chronicle of the crusades for the period 1095–1271, is written.[318]

1272

- 21 February. Charles I of Anjou proclaimed king of Albania.[319]

- 22 May. Lord Edward's Crusade, the last major crusade to the Holy Land, ends inconclusively with a ten-year truce with Baibars. Edward is attacked by an Assassin the next month.[320]

- 20 November. Edward I of England becomes king after the death of his father Henry III three days earlier.[321]

Decline and Fall of the Crusader States

[edit]The Mamluks under Baibars, later Qalawun, continued their onslaught on the Franks in the Levant, leading to the Fall of Tripoli in 1289 and, two years later, their successful Siege of Acre.[309] The West would never recover Jerusalem even though the Crusades continued for many centuries.[322]

1273

- 22 January. Muhammad II of Granada becomes the Nasrid ruler of the Emirate of Granada.[323]

- 11 March. Gregory X issues the papal bull Dudum super generalis asking for information on Islamic threats to Christendom.[324]

- Early. Haymo Létrange puts Beirut and their ruler Isabella of Beirut under the protection of Baibars.[325]

- July. Al-Kahf, the last Assassin stronghold in Syria, falls to the Mamluks.[326]

- 1 October. Rudolf I of Germany elected king, ending the Great Interregnum.[327]

- October. Philip of Courtenay becomes Latin Emperor upon the death of Baldwin II.[328]

- (Date unknown). William of Tripoli publishes De statu Saracenorum in response to the papal bull serving as a handbook for the Christian missionary on the history, law and beliefs of Islam.[329]

1274

- Early. Gregory X receives reports on the failure of the crusades including Gilbert of Tournai's Collectio de scandalis ecclesiae, Bruno of Olomouc's Relatio de statu ecclesiae in regno alemaniae, and Humbert of Romans' Opus tripartitum.[330]

- 7 May – 17 July. The Second Council of Lyon discusses reconquest of the Holy Land.[331] Representatives of the Ilkhanate attend and the Union of Churches approved.[332]

- (Date unknown). Byzantine forces are defeated by John I Doukas, ruler of Thessaly, at the Battle of Neopatras.[333]

- (Date unknown). The forces of Euboea and Crete are defeated by the Byzantines at the Battle of Demetrias.[333]

- (Date unknown). Geoffrey of Beaulieu writes his The Life of Saint Louis, a biography of Louis IX of France, as directed by the pope.[334]

1275

- March. Baibars continues his campaign against Armenia and demands the return of the Christian half of Latakia.[335]

- Spring. Marco Polo arrives at the court of Kublai Khan.[336]

- 13 May. Marinid forces led by Abu Yusuf Yaqub begin their first Invasion of Spain.[337]

- 4 June. Hugh III of Cyprus negotiates a truce with Baibars that protects Latakia in exchange for an annual tribute.[335]

- 8 September. The Moors defeat Castile at the Battle of Écija.[338]

- 21 October. The Moors defeat the army of Castile led by Sancho II de Aragon at the Battle of Martos. Sancho II was killed and Alfonso X of Castile was forced to accept a peace treaty.[339]

- (Date unknown). Philip III of France and Rudolf I of Germany take the cross without corresponding action.[340]

1276

- 19 January. Abu Yusuf Yaqub ends his Invasion of Spain, and, with Muhammad II of Granada, agrees to a truce with Alfonso X of Castile for two years.[337]

- October. The Knights Templar purchase La Fauconnerie (La Féve), omitting to secure the consent of Hugh III of Cyprus.[341]

- October. Hugh III of Cyprus relocates from Acre to Cyprus.[342]

1277

- January/March. Philip of Sicily dies and the title to the Principality of Achaea reverts to his father Charles I of Anjou.[343]

- 18 March. Charles I of Anjou secures the disputed title of king by purchasing Maria of Antioch's claim to the throne of Jerusalem.[344]

- 15 April. Mamluk forces defeat a Mongol occupying force at the Battle of Elbistan.[345]

- 25 November. Nicholas III is elected pope after the death of John XXI on 20 May 1277.[346]

- 1 July. Baibars dies and is succeeded by sons Barakah and then Solamish.[347]

- August. Abu Yusuf Yaqub begins his second Invasion of Spain, ravaging the districts of Jerez de la Frontera, Seville and Córdoba.[348]

- Approximate. The Estoire d'Eracles, a history of the Crusades, is written.[349]

1278

- January. Charles I of Anjou is crowned king of Jerusalem at Acre and is recognized by the kingdom's barons. He appoints Roger of San Severino as his representative.[350]

- 1 May. William of Villehardouin dies and his lands in Achaea revert to Charles I of Anjou.[351]

- 24 May. Charles I of Anjou swears fealty to Nicholas III and promises not to invade the Byzantine Empire.[352]

- 25 July. Castile defeated by the Marinids at the naval Battle off Algeciras.[353]

- 5 August. Alfonso X of Castile launches the unsuccessful first Siege of Algeciras. Castilian forces were commanded by Peter of Castile and Alfonso Fernández el Niño.[353]

1279

- 16 February. Alfonso III of Portugal dies and is succeeded by his son Denis of Portugal.[354]

- 5 March. The Teutonic Knights are defeated by Grand Duchy of Lithuania at the Battle of Aizkraukle.[355]

- November. Qalawun becomes Mamluk sultan after deposing Solamish.[356]

1280

- April–June. Sunqur al-Ashqar, Mamluk governor of Damascus, revolts against Cairo. He flees after Qalawun invades the city.[357]

- 23 June. The Emirate of Granada defeats Castile and León at the Battle of Moclín.[358]

- 22 August. Nicholas III dies suddenly and the 1280–1281 papal election begins 22 September.[359]

- 29 October. The Mongols sack Aleppo.[360]

- (Date unknown). The Byzantines defeat Sicily after the Siege of Berat.[361]

1281

- 22 February. Martin IV is elected pope.[362]

- 10 April. Byzantine emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos is excommunicated.[363][364]

- 3 May. Qalawun renews the truce with the Kingdom of Jerusalem for another ten years.[365]

- 16 July. Bohemond VII of Tripoli agrees to Qalawun's truce for the County of Tripoli.[365]

- 29 October. The Mamluks defeat a coalition of Mongols, Armenians and Hospitallers at the second Battle of Homs.[366]

1282

- January. Bohemond VII of Tripoli kills Guy II Embriaco, alienating the Genoese.[367]

- 30 March. The War of the Sicilian Vespers begins with European powers and the papacy vying for control of Sicily.[368]

- 28 April. Charles I of Anjou's fleet at Messina is sunk, and Mategriffon Castle is forced to surrender.[369]

- 1 May. Guelphs and Ghibellines fight at the Battle of Forti, with the Guelph army defeated.[370]

- 6 May. Tekuder becomes ruler of the Ilkhanate after the death of his brother Abaqa on 1 April, and soon converts to Islam taking the name Ahmad.[371]

- 25 August. Tekuder sends an embassy to Qalawun seeking an alliance.[372]

- 30 August. Peter III of Aragon lands in Sicily, claims the crown four days later and is excommunicated by Martin IV.[373][374]

- September/October. Hungary defeats the Cumans at the Battle of Lake Hód.[375]

- 11 December. Andronikos II Palaiologos becomes Byzantine emperor, succeeding Michael VIII Palaiologos.[376]

- (Date unknown). Roger of Lauria named commander of the Aragonese fleet.[377]

- (Date unknown). George Akropolites publishes his Annales (Chronike Syngraphe), the main Greek source for the period 1203–1261.[378]

1283

- 13 January. Martin IV declares the Aragonese Crusade against Peter III of Aragon.[379]

- Before 5 March. Ata-Malik Juvayni writes his Tarīkh-i Jahān-gushā (History of the World Conqueror), an account of the Mongol Empire.[380]

- 8 July 1283, Roger of Lauria defeats the Angevins at the Battle of Malta.[381]

- Late July. Hugh III of Cyprus sails for Acre, arriving in August to lukewarm reception.[382]

- Summer. The Prussian rebellion against the Teutonic Knights collapses.[383]

- (Date unknown). German pilgrim Burchard of Mount Sion writes Descriptio Terrae Sanctae (Description of the Holy Land) of his travels in Syria, Egypt and Armenia.[384]

1284

- 4 March. Hugh III of Cyprus dies in Tyre and his son John I of Cyprus crowned king of Jerusalem two months later. John is recognized as king only in Beirut and Tyre.[385]

- 4 April. Alfonso X of Castile dies and is succeeded by his son Sancho IV of Castile.[386]

- 5 June. Roger of Lauria defeats the Neapolitan fleet at the Battle of the Gulf of Naples, capturing the commander Charles II of Naples.[387]

- 5–6 August. Pisa is ruined after loss to Genoa at the naval Battle of Meloria.[388]

- 11 August. Arghun becomes the fourth ruler of the Ilkhanate after the murder of his uncle Tekuder.[389] He relies on advice from the patriarch Yahballaha III.[390]

- 16 August. Joan I of Navarre marries Philip IV of France, and thus Navarre forms a personal union with the Kingdom of France.[391] [392]

1285

- 7 January. Charles I of Anjou dies and is succeeded by his son Charles II of Naples, who also claims the crown of Jerusalem.[393]

- 28 March. Martin IV dies and Honorius IV is elected pope on 2 April.[394]

- 25 April – 24 May. Mamluks capture of the Hospitaller castle at Marqab.[395]

- 20 May. John I of Cyprus dies, and his brother Henry II of Cyprus is crowned king of Cyprus.[396]

- 26 June. Philip III of France invades Aragon in response to call to crusade of 1282.[397]

- 4 September. The Aragonese fleet commanded by Roger of Lauria defeats a French and Genoese at the Battle of Les Formigues.[398]

- 1 October. Aragon defeats the French at the Battle of the Col de Panissars.[399]

- 5 October. Philip IV of France becomes king upon the death of his father Philip III of France.[400]

- 5 October. Joan I of Navarre becomes queen consort of France by virtue of her marriage to Philip IV of France. Navarre goes under French rule.[401]

- Winter. The Teutonic Knights launch the Lithuanian Crusade.[402]

- (Date unknown). Arghun writes to Honorius IV proposing a military alliance against the Mamluks.[403]

- (Date unknown).The Second Mongol invasion of Hungary is unsuccessful, with the invaders retreating after just two months.[404]

1286

- March. Abu Yaqub Yusuf an-Nasr becomes Marinid sultan of Morocco upon the death of his father Abu Yusuf Ya'qub.[405]

- 24 June. Henry II of Cyprus returns to Acre.[406]

- 29 July. Angevin bailli Odo Poilechien, loyal to Charles II of Naples, hands the citadel over to Henry II at the insistence of the three military orders.[407]

- 15 August. Henry II of Cyprus is crowned king of Jerusalem at Tyre. A few weeks later, he returns to Cyprus after appointing Philip of Ibelin as regent.[396]

1287

- 22 March. A major earthquake strikes Syria causing serious damage to the walls of Latakia.[408]

- 3 April. Honorius IV dies and Rome enters into lengthy 1287–1288 papal election.[409]

- Easter. Arghun's ambassador to the West, Rabban Bar Sauma, enters Constantinople.[410]

- 20 April. Qalawun takes Latakia, claiming it is not covered by the truce of 1281.[411]

- 31 May. The Genoese fleet defeats the Pisan and Venetian fleets at Acre, and begins a blockade of the city.[412]

- 18 June. Rabban Bar Sauma records the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.[413]

- 23 June. Aragon defeats Naples at the naval Battle of the Counts.[414]

- 19 October. Bohemond VII of Tripoli dies, succeeded by his sister Lucia of Tripoli.[415]

- 6 December. The third Mongol raid into Poland begins.[416]

1288

- 28 October. Edward I of England enters into the Treaty of Canfranc with Alfonso III of Aragon to secure the release of Charles II of Naples, captured four years earlier.[387]

- Early. Lucia of Tripoli and her husband Narjot de Toucy arrive in Acre.[415]

- February. The Mongols are repulsed by Poland after the third of the Mongol raids into Poland.[416]

- 22 February. Nicholas IV becomes pope, immediately supports a crusade to the Holy Land.[417]

- 8 August. Nicholas IV declares a crusade against Ladislaus IV of Hungary.[418]

- 28 October. Edward I of England enters into the Treaty of Canfranc with Alfonso III of Aragon to secure the release of Charles II of Naples, captured four years before.[387]

- (Date unknown). Nicholas IV sends envoy Giovanni da Montecorvino to Persia and China.[419]

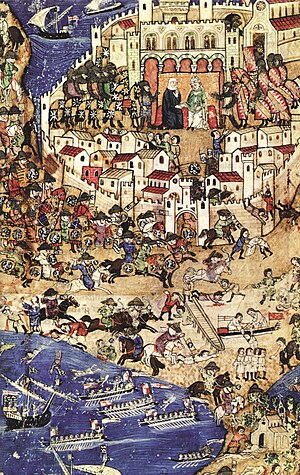

1289

- 27 March – 26 April. Mamluk sultan Qalawan begins the Siege of Tripoli, causing the fall of one of the last remnants of the kingdom in the Levant a month later.[420]

- Easter. Arghun sends Buscarello de Ghizolfi to Italy and France to announce that he intends to invade Syria in 1291.[421]

- May. Fort Nephin and Le Boutron are occupied by Qalawan. Peter Embriaco is allowed to retain his estates in Tripoli.[422]

- September. Jean de Grailly is sent to the West to appeal for help.[423]

- (Date unknown). Osman I forms what is to become the Ottoman Empire.[424]

- (Date unknown). Leo II of Armenia dies and is succeeded by his son Hethum II of Armenia.[425]

1290

- 10 February. Nicholas IV calls for a crusade against the Mamluks.[426]

- August. Venetian and Aragonese crusaders arrive at Acre, and instigate a massacre of Muslims in the city.[427]

- Fall. The Egyptian army mobilizes towards Acre.[428]

- 4 November. Qalawun leaves Cairo for Syria, en route to Acre. He dies six days later.[429]

- 10 November. Qalawun's son al-Ashraf Khalil becomes Mamluk sultan.[430]

1291

- 6 August. Genoese-Sevillian fleet led by Benedetto Zaccaria wins a victory over Marinid fleet at Alcácer Seguir.[431]

- Approximate. The annals of the Crusades Annales de Terre Sainte is written.[349]

- 12 March. Mongol Ieader Arghun dies, destablizing the Ilkhanate.[432]

- 4 April – 18 May. Crusaders lose their last stronghold in the Holy Land when Mamluk sultan Khalil successfully executes the Siege of Acre.[433][434]

- May–July. Tyre, Sidon, Beirut surrender to Mamluks.[435]

- 18 June. Alfonso III of Aragon dies and is succeeded by his brother James II of Aragon.[436]

- 15 July. Rudolf I of Germany dies,[437] and is succeeded by his son Albert I.[438]

- 30 July. Mamluks occupy Haifa.[439]

- 3–14 August. Templar castles Tortosa and Château Pèlerin evacuated, but retain their presence on the island fortress of Ruad. The Fall of Ruad to the Mamluks on 26 September 1302 marks ends the presence of the Crusaders in the mainland of the Levant.[439]

See also

[edit]- A History of the Crusades: list of contributions

- Bibliography of the Crusades: modern works

- Chronology of the later Crusades through 1400

- Chronology of the Crusades after 1400

- Historians and histories of the Crusades

Notes

[edit]- ^ Urban III allegedly collapsed when hear the news of the loss of Jerusalem, but William of Newburgh believed that the pope died before he heard the news.[4]

- ^ Richard the Lionheart famously refused to show deference to Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor and declared to him, "I am born of a rank which recognises no superior but God".[62]

- ^ The leaders of the Fourth Crusade were Boniface of Montferrat, Enrico Dandolo, Theobald III of Champagne, Baldwin of Flanders, Louis of Blois, Hugh IV of Saint-Pol, Conrad of Halberstadt, Martin of Pairis andConon de Béthune

- ^ The Cathars were also known as the Albigensians. Saint Dominic would later form the Dominicans.

- ^ Arnaud Amalric reportingly said of the residents when asked how to distinguish Cathars from Catholics: "Kill them. The Lord knows those that are his own."

References

[edit]- ^ Wolff & Hazard 1969, The Later Crusades.

- ^ a b Nicolle 2005a, The Third Crusade.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 462–466, The Siege of Jerusalem.

- ^ Lock 2006, p. 72, Death of Urban III.

- ^ James Francis Loughlin (1909). "Pope Gregory VIII". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Smith, Thomas W. (2018). "Audita Tremendi and the Call for the Third Crusade Reconsidered, 1187–1188". Viator. 49 (3): 63–101. doi:10.1484/J.VIATOR.5.119574.

- ^ Henry W. Davis (1911). "Richard I". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Runciman 1952, pp. 470–472, Defense of Tyre.

- ^ James Francis Loughlin (1908). "Pope Clement III". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ a b Riley-Smith 1967, pp. 109–111, Siege of Belvoir Castle.

- ^ Skovgaard-Petersen, Karen (2001). A Journey to the Promised Land: Crusading Theology in the Historia de Profectione Danorum in Hierosolymam (c. 1200). Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. 35–37, 70, 75.

- ^ Bengt Liljegren (2004). Rulers of Sweden. Historiska Media.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Henry II "the Saint". Encyclopædia Britannica. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pgs. 273–274.

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Philip II, king of France. Encyclopædia Britannica. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pgs. 378–381.

- ^ Fred A. Cazel (1955). “The Tax of 1185 in Aid of the Holy Land.” Speculum, Vol. 30, No. 3, ppgs. 385–392.

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Frederick I, Roman Emperor. Encyclopædia Britannica. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pgs. 45–46.

- ^ Lock 2006, p. 73, Guy of Lusignan.

- ^ Johnson 1969, pp. 87–122, Barbarossa's ultimatum to Saladin.

- ^ Conder 1897, pp. 129–130, Siege of Laodicea.

- ^ Conder 1897, pp. 130–132, Sieges of Sahyun Castle and al-Shughur.

- ^ a b Conder 1897, pp. 130–134, Sieges of Sahyun Castle, al-Shughur and Bourzey.

- ^ Michael S Fulton (2024), Crusader Castle: The Desert Fortress of Kerak. pgs. 72–74.

- ^ Lane-Poole 1898, p. 248, Fall of Safed.

- ^ Johnson 1969, pp. 87–122, The Crusades of Frederick Barbarossa and Henry VI.

- ^ a b Jonathan Wilson (2020). ““Neither age nor sex sparing”: the Alvor massacre 1189, an anomaly in the Portuguese Reconquista?” Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies 12, pgs. 199–229.

- ^ Thomas Andrew Archer (1896). "Richard I" . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 46. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pgs. 136–145.

- ^ Dana Cushing (2017). “The Siege of Silves in 1189: Attacked with Siege-Engines and Arrows.” Medieval Warfare, Vol. 7, No. 5, pgs. 48–53.

- ^ Johnson 1969, pp. 94–96, Philippopolis.

- ^ Hosler 2018, p. The Siege of Acre, 1189–1191.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Tancred (Sicily). Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pg. 395.

- ^ Painter 1969a, pp. 45–86, The Third Crusade: Richard the Lionhearted and Philip Augustus.

- ^ Kennedy 1994, pp. 43–44, Beaufort Castle.

- ^ a b Charles Wendell David (1939). “Narratio de Itinere Navali Peregrinorum Hierosolymam Tendentium et Silviam Capientium, A. D. 1189.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 81, No. 5, pp. 591–676.

- ^ Aleksandar Stoyanov (2019). The Size of Bulgaria's Medieval Field Armies: A Case Study of Military Mobilization Capacity in the Middle Ages. The Journal of Military History, 83(3), pgs. 719–746

- ^ Loud 2010, pp. 95–106, Battle of Philomalion.

- ^ Johnson 1969, pp. 111–112, Battle of Iconium.

- ^ Hamilton White (2021). The Tomar Hoard. Dolman Scott Publishing, pg. 23.

- ^ a b c Isabella I, Queen of Jerusalem. Britannica.

- ^ a b Painter 1969b, pp. 59–60, Richard the Lionheart at Messina.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 36–38, King Tancred of Sicily.

- ^ a b Conrad of Montferrat, King of Jerusalem. Britannica.

- ^ Thomas Joseph Shahan (1908). "Pope Celestine III". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ a b Painter 1969b, pp. 63–64, Richard at Limassol.

- ^ a b c Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Henry VI (Roman emperor). Encyclopædia Britannica. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pg. 278.

- ^ Painter 1969b, pp. 64–65, Conquest of Cyprus.

- ^ William Hunt (1885). "Berengaria" . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography, Vol. 4, pgs. 325–326.

- ^ a b Painter 1969b, pp. 67–69, Siege of Acre.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 53–55, Massacre at Ayyadieh.

- ^ Sidney Dean (2014). “‘Crusader King’: From Arsuf to the Treaty of Jaffa.” Medieval Warfare, Vol. 4, No. 5, pgs. 27–34

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 57–58, Richard's victory.

- ^ Conder 1897, pp. 360–361, The Sultan's expedition.

- ^ Robert Nisbet Bain (1911). "Canute VI". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pgs. 222–223.

- ^ Patrick A. Williams (1970). "The Assassination of Conrad of Montferrat: Another Suspect?". Traditio 26 Fordham University: 381–389

- ^ Luigi Villari (1911). "Dandolo". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pgs. 801–802.

- ^ Battle of Jaffa. Britannica.

- ^ Richard the Lionheart Makes Peace With Saladin. Jewish Virtual Library.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 73–75, Treaty between Saladin and Richard.

- ^ a b Runciman 1954, p. 74, Cæur-de-Lion.

- ^ a b Ernest Barker (1911). "The Teutonic Order". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pgs. 676–679.

- ^ Henry W. Davis (1911). "Richard of Devizes". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pg. 298.

- ^ Anne-Marie Eddé (2021). al-Malik al-Afḍal b. Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn. Encyclopaedia of Islam Three Online.

- ^ Longford 1989, p. 85.

- ^ Riley-Smith 1998, p. 12, Chronology, 1191–1216.

- ^ Henry W. Davis (1911). "John of England". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press, pgs. 439–440.

- ^ Casimir II the Just. Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ^ Jochen Burgtorf (2016). The Antiochene War of Succession, pg. 199. In Boas, Adrian J. (ed.). The Crusader World. University of Wisconsin Press.

- ^ Battle of Arcadiopolis. Byzantine Battles.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nicholas Aloysius Weber (1907). "Albigenses". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company, pgs. 267–269.

- ^ John Bagnell Bury (1911). "Alexius III". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pg. 577–578.

- ^ Donvito, Philippo (2005). "Queen Tamar of Georgia (1184-1213): The Lioness of the Caucasus". Medieval Warfare. IV-2: Female Knights and Fighting Princesses - Medieval Women as Warriors: 19–23.

- ^ Battle of Alacos. Britannica.

- ^ Tsurtsumia, Mamuka (2014). "Couched Lance and Mounted Shock Combat in the East: The Georgian Experience". In Rogers, Clifford J.; DeVries, Kelly; France, John (eds.). Journal of Medieval Military History. Vol. XII. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell & Brewer Ltd. pp. 89–90. ISBN 9781843839361.

- ^ Michal Lower (2014). “The Papacy and Christian Mercenaries of Thirteenth-Century North Africa.” Speculum 89: 601–631.

- ^ Louviers, Treaty of (1196). The Oxford Companion to British History.

- ^ Second Bulgarian Empire. HistoryMaps.

- ^ Henry W. Davis (1911). "Ambrose (poet)". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pg. 798.

- ^ Kaufmann Kohler and Louis Ginzberg (1906). Ephraim B. Jacob. JewishEncyclopedia.

- ^ Graham A. Loud (2014). "The German Crusade of 1197–1198". Crusades. 13: 143–172.

- ^ Jean Richard (1979), The Latin Kingdom Of Jerusalem. North Holland Publishing, pg. 204.

- ^ Hardwicke 1969, p. 529, Death of Henry I of Jerusalem.

- ^ Johnson 1969, pp. 116–122, The Crusades of Henry VI.

- ^ a b Alan V. Murray (2015), The Crusades to the Holy Land, The Essential Reference Guide. ABC–CLIO, pg. 127.

- ^ a b c Riley-Smith 1998, p. 12, Chronology of the Crusades in North Africa.

- ^ Ruibal Rodríguez, Amador (1992). "La arquitectura militar de la frontera musulmana, en Castilla, en torno al 1200. El caso de Salvatierra" (PDF). El arte español en épocas de transición. Universidad de León. p. 40.

- ^ McNeal & Wolff 1969, pp. 153–186, The Fourth Crusade.

- ^ Michael Ott (1910). "Pope Innocent III". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ a b Hardwicke 1969, pp. 529–532, Aimery of Cyprus.

- ^ Ryan 2008, p. 10, Post miserabile.

- ^ MIchael Ott (1907). "Berthold". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ William Hunt (1892). "John (1167?–1216)". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 29. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pgs. 402–417.

- ^ Louis René Bréhier (1909). "Foulque de Neuilly". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Edgar H. McNeal (1953). “Fulk of Neuilly and the Tournament of Écry.” Speculum, Vol. 28, No. 2, pgs. 371–375.

- ^ Florence Jullien (2006). "Michael the Syrian". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Online edition.

- ^ R. S. Humphreys (2011). "Ayyubids". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. III, Fasc. 2, pgs. 164-167.

- ^ Tyerman 2006, pp. 689–694, Livonia, 1188–1300.

- ^ Myriam Greilsammer (1995). Le livre au roi. Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres

- ^ McNeal & Wolff 1969, pp. 162–163, The Venetians and the Crusade.

- ^ Runciman 1954, p. 111, Boniface of Montferrat.

- ^ a b c Charles M. Brand (1968). “A Byzantine Plan for the Fourth Crusade.” Speculum, Vol. 43, No. 3, pgs. 462–475.

- ^ Louis René Bréhier (1908). "Enrico Dandolo". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Lock 2006, p. 83, Crusaders arrive at Acre.

- ^ Hardwicke 1969, p. 533, War of the Antiochene Succession.

- ^ Siege of Zara. Britannica.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 114–116, The Sack of Zara.

- ^ Lind 2006a, pp. 436–439, Finland and the Crusades.

- ^ Order of the Brothers of the Sword. Britannica.

- ^ Phillips 2005, p. 113, Departure for Constantinople.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 116–118, Siege of Constantinople.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Isaac II (Angelus). Encyclopædia Britannica. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pg. 858.

- ^ McNeal & Wolff 1969, p. 180, Letter to Innocent III from the Crusaders.

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Alexius V. Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pg. 578.

- ^ John C. Moore (1962). “Count Baldwin IX of Flanders, Philip Augustus, and the Papal Power.” Speculum, Vol. 37, No. 1, 1962, pgs. 79–89.

- ^ A. A. Vasiliev (1936). “The Foundation of the Empire of Trebizond (1204-1222).” Speculum, Vol. 11, No. 1, pgs. 3–37.

- ^ A. Carole (1965). "Partitio terrarum imperii Romanie". Studi Veneziani. 7: 125–305.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 129–130, Innocent III condemns the Crusade.

- ^ Lock 2006, p. 87, The end of the Crusade.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 90, Theodore I Laskaris.

- ^ Wolff 1969, Nicaea-Latin wars.

- ^ Boas, Adrian (2015). The Crusader World. Routledge. p. 229.

- ^ a b c d e Fine 1994, Bulgarian-Latin wars.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 103–104, Maria of Montferrat.

- ^ Fine 1994, pp. 62–70, Battle of Kountouras.

- ^ Michel Kursanskis (1988). L'empire de Trébizonde et les Turcs au 13e siècle. Revue des études byzantines 46, pgs. 109–124.

- ^ A. von Reumont (1871). "Der Herzog von Athen". Historische Zeitschrift (in German). 26 (1): 1–74.

- ^ Andrew Holt (2005). Gunther von Pairis. Crusades-Encyclopedia.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Henry of Romania. Encyclopædia Britannica. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pg. 280.

- ^ John Bonaventure O'Connor (1909). "St. Dominic". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 5. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Acominatus, Michael. Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pgs. 150–151.

- ^ "Terra Mariana". The Encyclopedia Americana. Americana Corp. 1967.

- ^ Claude Cahen (1968). Pre-Ottoman Turkey: A General Survey of the Material and Spiritual Culture and History c. 1071-1330, pg. 119f

- ^ Evans 1969, pp. 277, Pierre de Castelnau.

- ^ a b c Paul Daniel Alphandéry (1911). "Albigenses". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press, pgs. 505–506.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 94, Battle of Philippopolis.

- ^ Costen 1997, p. 121, Massacre at Béziers.

- ^ a b c Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). John of Brienne. Encyclopædia Britannica. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pg. 442.

- ^ Peter II, King of Aragon. Britannica.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, p. 717, Battle of Antioch on the Meander.

- ^ a b Charles M. Brand. (1991). "Rhyndakos River". In Kazhdan, Alexander (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Zacour 1969, pp. 325–342, The Children's Crusade.

- ^ Guy Perry (2015). “Isabella II or Yolanda? The Name of the Queen of Jerusalem and Spouse of the Emperor Frederick II.” Medieval Prosopography, Vol. 30, pgs. 73–86.

- ^ Werthschulte, Leila (2016). "Arnold of Lübeck". Encyclopedia of the Medieval Chronicle.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Wolfram von Eschenbach. Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pgs. 775–776.

- ^ Van Cleve 1969a, pp. 277–428, The Fifth Crusade.