Battle of Lake Hód

| Battle of Lake Hód | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Feudal anarchy in Hungary | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Kingdom of Hungary | Cumans | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

King Ladislaus IV Roland Borsa Roland Rátót | Oldamir | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 3,000[1] | 2,500[1] | ||||||

The Battle of Lake Hód (Hungarian: Hód-tavi csata) was fought between the Kingdom of Hungary and the Cumans in September or October 1282. King Ladislaus IV of Hungary successfully repelled the invaders.

Background

[edit]In the midst of imminent danger of the Mongol invasion, the first Cumans settled in the Kingdom of Hungary, after King Béla IV of Hungary offered refuge to Khan Köten (Kötöny) and his people in 1239.[2] The king's decision caused social, economic and political tension and the settlement of masses of nomadic Cumans in the plains along the river Tisza gave rise to many conflicts between them and the local villagers. When the Mongols reached the border and invaded Hungary in the spring of 1241, several Hungarians accused Köten and their Cumans of cooperating with the enemy. The Cumans left Hungary amid plunder, after an angry mob massacred Köten and his retinue in Pest. With their departure Béla lost his most valuable allies and the Mongols decisively defeated his royal army in the Battle of Mohi on 11 April 1241.[3] Following the withdrawal of the Mongols in the next year, Béla invited the Cumans to return and settle in the depopulated plains between the rivers Danube and Tisza, in return for their military service. He even arranged the engagement of his firstborn son, Stephen, who was crowned king-junior in or before 1246, to Elizabeth, a daughter of a Cuman chieftain.[4][5]

The issue of the social integration of the Cumans had marginalized in the following decades.[6] Their military value became a significant portion within the Hungarian royal army, which also contributed to the formation of the light cavalry structure. Cumans participated in military campaigns abroad, for instance during the fights against the Duchy of Austria and the Kingdom of Bohemia.[7][8] In the civil war between King Béla IV and his son Stephen, both sides tried to gain Cuman support.[9] During this conflict, in 1264, Béla sent Cuman troops to fight his son Stephen, despite that the Cumans officially belonged to the suzerainty of the latter, who had taken the title of "Dominus Cumanorum". After Stephen's victory in the civil war, significant number of Cumans intended to leave Hungary amid looting and plunder, however, they were important militarily to the royal authority. Around April 1266, Stephen successfully persuaded them to remain in Hungary, when launched a punitive expedition against them.[10][11]

After the death of Stephen V in 1272, the 10-year-old Ladislaus IV (subsequently also known as Ladislaus the Cuman) ascended the Hungarian throne under the regency of his mother Elizabeth the Cuman, but in fact, baronial parties administered the kingdom. Hungary fell into feudal anarchy, when various groups fought for supreme power. Between 1277 and 1279, Ladislaus, who was declared to be of age, has temporarily succeeded in domestic and foreign policy.[12] Pope Nicholas III sent Philip, Bishop of Fermo, to Hungary to help him restore royal power in early 1279. However, the arrival of the papal legate had an overall negative impact on domestic political stability. The bishop sensed angrily that majority of the Cumans has retained their pagan religion and customs in recent decades within a Christian realm. Philip extracted a ceremonious promise from the Cuman chieftains of giving up their pagan customs, and persuaded the Hungarian monarch to swear an oath to enforce the keeping of the Cuman chieftains' promise. During the assembly at Tétény in the summer of 1279, the so-called Cuman laws were passed, which prescribed social and cultural assimilation of the Cumans.[13][14] They, however, did not obey the laws, and Ladislaus IV, himself being also of half-Cuman descent, failed to force them. As a result, Philip excommunicated the monarch and placed Hungary under interdict shortly thereafter. After mutual imprisonment and political struggles, Ladislaus IV took a new oath to enforce the Cuman laws in the spring of 1280.[15] In response, many Cumans decided to leave Hungary instead of obeying the legate's demands. This fundamentally endangered the effectiveness of the Hungarian military capability. The king was chasing the outgoing Cumans as far as Szalánkemén (now Stari Slankamen in Serbia), but could not hinder them from crossing the frontier.[13] According to the king's donation letter to Thomas Talpas in 1288, the Hungarian army crossed the Southern Carpathians in order to bring back the "secretly defected Cumans from the borderlands of the Tartars".[16] The Cuman invasion of Hungary occurred following that.

Date and location

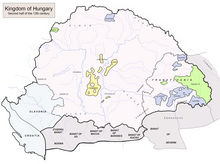

[edit]Pre-19th century historiography claimed that the battle took place at the Lake Hód that once existed, near present-day Hódmezővásárhely. Late 19th-century historiography – Károly Szabó and Gyula Pauler – considered the Cuman's incursion and the Battle of Lake Hód took place in early August 1280, based on a royal charter – contains that a certain castle warrior Denis is granted nobility because of his participation – which later proved to be a forgery.[17] Historians István Gyárfás and Károly Szabó considered the place of the battle was a settlement [locus] called Hód instead of a lake [lacus]. Gyula Pauler placed the battle site to a field called Hód near Makó. According to Pauler's reconstruction, the Cumans rebelled against Ladislaus IV, when the monarch took his second oath to enforce the Cuman laws after his liberation from captivity. They plundered the region between the area of rivers Tisza and Maros (Mureș), until they were defeated by Ladislaus IV in the Battle of Lake Hód in August 1280. Thereafter, the king marched to Székesfehérvár and gathered an army in the autumn of 1280 to persuade the outgoing Cumans to stay in Hungary.[18]

In his study published in 1901, historian János Karácsonyi put the date of the battle to late April or early May 1282. He argued the diplomas Pauler had previously put forward as an argument, only refer to domestic rebellion of the Cumans occurred in the autumn of 1280, while other charters suggest that the Battle of Lake Hód chronologically took place after the siege of the castle of Szalánc (today Slanec, Slovakia) and the defeat of Finta Aba, a rebellious lord, which occurred in 1281. In addition, Karácsonyi proved that the aforementioned charter (allegedly issued on 21 August 1280) regarding the ennoblement of Denis (ancestor of the Mokcsay family) is non-authentic. The historian emphasized that the Illuminated Chronicle mentions the skirmish under the year 1282, while Ladislaus Miskolc, one of the participants, who was killed in the battle, is mentioned as a living person in 1281. In that year, the king launched a campaign against Finta Aba, which covered about the entire year. In addition, a royal charter from 1283 listed Ladislaus' victories in the following chronological order: Battle on the Marchfeld (1278), Siege of Szalánc (1281) and the Battle of Lake Hód, while another royal charter from the next year states that the battle took place before the siege of Bernstein Castle (Borostyánkő), which occurred in 1284.[19] In another study (1907), Karácsonyi cited another document, which proves that Demetrius Rosd, who also fell in the battle, was still alive in the first months of 1282.[20] In summary, Karácsonyi argued the Cumans' revolt took place in the autumn of 1280; they intended to leave Hungary, and Ladislaus IV was unable to defeat the Cumans and prevent them from doing so. A year and a half later, in the spring of 1282, the Cumans led by a certain Oldamir (also Oldomerus or Oldamur) invaded the kingdom, but the monarch repelled their attack at the Lake Hód.[21]

Local historian Károly Czímer – while accepted the date 1282 – refused the identification of the place of the battle with the area of Hódmezővásárhely, arguing that the two sites were first connected in the 18th century by local Calvinist pastor and scholar Benjámin Szőnyi. This tradition is rooted locally in Hódmezővásárhely, then was integrated into the national historiography too throughout the 19th century.[22] Czímer claimed that the battle took place near the village of Hód in Arad County, later called Temesszécsény (present-day Seceani in Timiș County, Romania), arguing that the village and the surrounding area lay along the usual military marching area of the Cumans.[23] Czímer's theory has not been embraced by the subsequent historiography, while the area of Hódmezővásárhely was unanimously accepted.[24]

Despite Karácsonyi's new research in the early 20th century, later scholars were divided on the question of when the battle took place. Bálint Hóman put the date to 1280, accepting Gyula Pauler's argument, in the interwar period, in addition to the first volume of the 1960s academic history series (Magyarország története 1.: Magyarország története az őskortól 1526-ig) during the Communist regime.[25] Historian Gyula Kristó considered the battle took place in the summer of 1280 (although he mentioned the other theory),[26] while his frequent scientific opponent György Györffy narrated the event under the year 1282.[27] In his 1977 study, László Blazovich contested Karácsonyi's arguments regarding the date 1282. He argued the authenticity of all three charters, which suggest that the battle took place in that year, is questionable, while there are other documents, where the military events of the 1280s are mentioned in a different order. Blazovich also questioned the credibility of the victim list of the battle provided by the contemporary Simon of Kéza's The Deeds of the Hungarians, because the chronicler presumably "could not distinguish between warriors who had fallen in battle and those who had recovered from their serious injury". According to Blazovich's interpretation, there was only a single skirmish between the monarch and the Cumans in the summer of 1280. In a response to the adoption of the Cuman laws, they rebelled against the royal power and devastated the region between the area of rivers Tisza, Maros and Körös (for instance, they stormed Egres Abbey, Hájszentlőrinc Chapter and Sövényvár Castle). Ladislaus IV gathered his army consisted of nobles from Northeast Hungary and Transylvania, and marched from Várad (today Oradea, Romania) to the area, where he defeated them at the Lake Hód in late October or early November 1280.[28]

Several historians – e.g. Gyula Kristó, András Pálóczi Horváth and Rózsa Zsótér – accepted Blazovich's argument and considered the battle took place in the autumn of 1280.[29][30][31] Zsótér claimed the battle occurred around 16 or 17 August 1280 or – if the year 1282 is correct – between around September and October 1282 based on the data of King Ladislaus' itinerary, when the monarch resided in Szeged.[31] In contrast, other historians continued to support Karácsonyi's interpretation and considered 1282 as the year of the clash, for instance, László Solymosi, András Borosy, György Székely and Jenő Szűcs.[29][32][33] Historian Attila Zsoldos rejected Blazovich's critics in his 1997 study. He emphasized the reward of those who took part in the battle appears first since 1283 (excluding non-authentic charters), which makes it more likely that the clash took place not long before, the previous year. He also emphasized Simon of Kéza's reliability with contemporary documents regarding the list of victims, while Zsoldos presented another document, which confirms that John Parasznyai, one of the participants, who was killed in the battle, was still alive in 1281.[34] Zsoldos provided the following reconstruction after separating the events for 1280 and 1282, respectively: Ladislaus gathered an army around October possibly near Várad and chased the outgoing Cumans as far as Szalánkemén in the autumn of 1280 (he issued his charter there on 11 November) and also crossed the border at the Carpathians.[16] Accordingly, there were no clashes in that year in Hungary between the king and the Cumans. Zsoldos argued Ladislaus IV successfully persuaded the Cumans to return to Hungary during the military campaign to Transalpina under unknown circumstances.[35] Zsoldos considered the rebellion broke out around July 1282 among the Cumans who were forced to return two years earlier. They looted and pillaged the region between the rivers Tisza and Maros. This conflict elevated into the Battle of Lake Hód sometime between 17 September and 21 October 1282.[36] Regarding English-language publications, orientalist István Vásáry accepted Zsoldos' interpretation,[37] while Nora Berend also supported the date 1282, referring to Zsoldos' study.[38] Pál Engel dated the battle to the year 1282 too.[39] Romanian historian Tudor Sălăgean also shared Zsoldos' reconstruction of the events, when narrated it from the perspective of Transylvania.[40] Tamás Kádár, who compiled the itinerary of Ladislaus IV, inserted the supposed date of the Battle of Lake Hód sometime between September and October 1282, in accordance with Zsoldos' interpretation.[41]

Battle

[edit]King Ladislas was noble, spirited, and ambitious, and when he learnt that the Cumans were plotting treason against him, he set out to make war on them. There was a fierce battle, which ended in utter defeat for the Cumans. A great many were killed; others abandoned their wives, children, and all their possessions and fled to the barbarian peoples. The few who are left are so abjectly subject to the King's authority that their hearts tremble in his presence and they scarcely dare look him in the face.

[...] Then in the year of our Lord 1282 Oldamir, leader of the Cumans assembled an army of Cumans near the lake which is called Hód with the intention to invade and make subject the kingdom of the Hungarians. King Ladislas, like the brave Joshua, went out against him to fight for his people and his realm. [...] A most fierce battle was joined between the two armies, but by divine clemency a sudden and unexpected shower of rain drove in the faces of the pagans, and the downpour was so heavy that they who had put their hope in bows and arrows became, as in the words of the prophet, as dung for the earth. Thus King Ladislas, trusting in divine help, obtained victory.

The battle is mentioned by the contemporary Simon of Kéza's The Deeds of the Hungarians in its last entry, the 14th-century Illuminated Chronicle and 19 royal charters of King Ladislaus IV.[44]

According to Attila Zsoldos, the monarch was informed on the Cuman revolt, when held a general assembly near Patak Castle (today ruins near Sátoraljaújhely) in July 1282, after capturing the fort from the forces of the rebellious lord Finta Aba. If the narration of the Illuminated Chronicle is authentic, the rebellion was led by Oldamir, "leader" or "prince of the Cumans" (dux Cumanie), which suggests that the Cumans in Hungary called on their relatives living under Mongol suzerainty for assistance. Although Simon of Kéza does not refer to the Cuman chieftain, but says about they "were plotting treason" against the king. Zsoldos claimed the devastation of the region between the rivers Tisza and Maros took place in the 1282 invasion: for instance, they attacked and burnt the monastery at Egres, where a large amount of royal treasury was kept.[36] It is plausible that they also plundered the estates of Thomas Csanád (although the document which narrates his ordeals is a non-authentic forgery). Rubinus Hermán and his udvornici from Vép successfully defended the fort of Sövényvár.[18]

In response to the Cuman attack, Ladislaus IV instantly summoned a royal army joined by nobles, knights and castle warriors in Northeast Hungary, mostly from Sáros, Ung and Zólyom counties.[18] With his army, Ladislaus marched into south and camped out at Szeged in order to await for the arrival of reinforcements from Transdanubia, including the queen's folk. Ladislaus and his army marched into the area of present-day Hódmezővásárhely, where they defeated the Cumans. Some of them fled the kingdom through the Southern Carpatian border, while others surrendered and swore loyalty to the king and their compliance with the 1279 Cuman law. After his victory, Ladislaus returned to Szeged, where he summoned another general assembly. The king arrived to Buda shortly before 2 November 1282.[41][45]

Several young noblemen, who subsequently became powerful and important barons of the realm by the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, had participated in the battle, for instance Roland Borsa – the Illuminated Chronicle refers to him as a "brave warrior", who "hurled himself with his spear upon the Cumans with impetuous courage and to his great renown smote them and struck them down in great numbers" –,[43] Amadeus Aba, Stephen Ákos, Roland Rátót and plausibly Dominic Rátót. Károly Czímer considered that Roland Borsa served as general of the vanguard, while Roland Rátót functioned as his deputy.[46][47] Ladislaus' loyal partisans were also present in large numbers, including brothers Thomas Baksa and George Baksa,[18] in addition to lesser nobles, e.g. Thomas Talpas, Sebastian Vejtei and Rophoin Debreceni.[48] Probably both sides suffered significant losses. Contemporary documents say Lawrence Rátót (son of Stephen Rátót), Dominic Gutkeled, John Bő and John Parasznyai were killed in the battlefield.[18][49] Furthermore, Simon of Kéza's chronicle provides a detailed list of that younger nobles who perished in the skirmish. Accordingly, among the fallen soldiers were Oliver Aba (from his clan's Rédei [Rhédey] branch), Andrew Igmánd, Ladislaus Miskolc (son of Panyit Miskolc) and Demetrius Rosd (son of Michael Rosd).[50]

András Pálóczi Horváth emphasized the Cumans' defeat at Lake Hód resulted "a reduction in the Cuman population in Hungary, and with this their economic and military strength was also greatly diminished".[30] According to Jenő Szűcs, the territory between the rivers Maros and Körös, in addition to Temesköz (Banat) ceased to be Cuman-inhabited areas following the battle.[33] György Györffy argued their defeat marked the beginning of the "feudalization" (i.e. social integration) of the Cuman subjects to the political, social and cultural structure of majority society, which lasted throughout the 14th century. At the same time, the Cumans appear less and less in contemporary sources as a separate entity, which indicate their complete social, linguistic and cultural assimilation to the Hungarian nation despite their surviving privileged territory called Kunság until the late 19th century.[51]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Czímer 1929, p. 411.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 99.

- ^ Berend 2001, p. 196.

- ^ Sălăgean 2016, p. 65.

- ^ Berend 2001, p. 261.

- ^ Czímer 1929, p. 398.

- ^ Berend 2001, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Pálóczi Horváth 1989, pp. 68–73.

- ^ Nagy 2013, p. 74.

- ^ Szűcs 2002, pp. 173, 178.

- ^ Berend 2001, p. 145.

- ^ Zsoldos 1997, pp. 80–81.

- ^ a b Szűcs 2002, pp. 417–427.

- ^ Pálóczi Horváth 1989, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Zsoldos 1997, pp. 83–86.

- ^ a b Zsoldos 1997, pp. 86–88.

- ^ Pauler 1899, p. 561.

- ^ a b c d e Pauler 1899, pp. 370–371.

- ^ Karácsonyi 1901, pp. 630–633.

- ^ Karácsonyi 1907, p. 948.

- ^ Blazovich 1977, p. 942.

- ^ Czímer 1929, pp. 386–389.

- ^ Czímer 1929, p. 397.

- ^ Blazovich 1977, p. 941.

- ^ Zsoldos 1997, p. 75.

- ^ Kristó 1981, p. 174.

- ^ Györffy 1953, p. 259.

- ^ Blazovich 1977, pp. 943–945.

- ^ a b Zsoldos 1997, p. 76.

- ^ a b Pálóczi Horváth 1989, p. 80.

- ^ a b Zsótér 1991, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Érszegi & Solymosi 1981, pp. 176–177.

- ^ a b Szűcs 2002, p. 428.

- ^ Zsoldos 1997, pp. 77–79.

- ^ Zsoldos 1997, p. 89.

- ^ a b Zsoldos 1997, p. 95.

- ^ Vásáry 2005, p. 106.

- ^ Berend 2001, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Engel 2001, p. 109.

- ^ Sălăgean 2016, p. 133.

- ^ a b Kádár 2016, p. 34.

- ^ Simon of Kéza: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 75), p. 157.

- ^ a b The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 180), p. 333.

- ^ Czímer 1929, p. 385.

- ^ Zsoldos 1997, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Czímer 1929, p. 412.

- ^ Nagy 2013, p. 84.

- ^ Karácsonyi 1901, p. 634.

- ^ Zsoldos 1997, p. 79.

- ^ Czímer 1929, pp. 407–409.

- ^ Györffy 1953, pp. 263–266.

Sources

[edit]Primary sources

[edit]- Simon of Kéza: The Deeds of the Hungarians (Edited and translated by László Veszprémy and Frank Schaer with a study by Jenő Szűcs) (1999). CEU Press. ISBN 963-9116-31-9.

- Bak, János M.; Veszprémy, László; Kersken, Norbert (2018). Chronica de gestis Hungarorum e codice picto saec. XIV [The Illuminated Chronicle: Chronicle of the deeds of the Hungarians from the fourteenth-century illuminated codex]. Budapest: Central European University Press. ISBN 978-9-6338-6264-3.

Secondary sources

[edit]- Berend, Nora (2001). At the Gate of Christendom: Jews, Muslims and "Pagans" in Medieval Hungary, c. 1000–c.1300. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-02720-5.

- Blazovich, László (1977). "IV. László harca a kunok ellen [Ladislaus IV's Fight against the Cumans]". Századok (in Hungarian). 111 (5). Magyar Történelmi Társulat: 941–945. ISSN 0039-8098.

- Czímer, Károly (1929). "Az 1282. évi hódi csata helye és lefolyása [Location and Course of the Battle of Hód in 1282]". Hadtörténelmi Közlemények (in Hungarian). 30 (1). Hadtörténeti Intézet és Múzeum: 385–416. ISSN 0017-6540.

- Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526. I.B. Tauris Publishers. ISBN 1-86064-061-3.

- Érszegi, Géza; Solymosi, László (1981). "Az Árpádok királysága, 1000–1301 [The Monarchy of the Árpáds, 1000–1301]". In Solymosi, László (ed.). Magyarország történeti kronológiája, I: a kezdetektől 1526-ig [Historical Chronology of Hungary, Volume I: From the Beginning to 1526] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 79–187. ISBN 963-05-2661-1.

- Györffy, György (1953). "A kunok feudalizálódása [The Feudalization of the Cumans]". In Székely, György (ed.). Tanulmányok a parasztság történetéhez Magyarországon a 14. században (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 248–275.

- Kádár, Tamás (2016). "IV. László király itineráriuma (1264–[1272]–1290) [The Itinerary of King Ladislaus IV (1264–[1272]–1290)]". Fons. 23 (1). Szentpétery Imre Történettudományi Alapítvány: 3–64. ISSN 1217-8020.

- Karácsonyi, János (1901). "A hód-tavi csata éve [The Year of the Battle of Lake Hód]". Századok (in Hungarian). 35 (7). Magyar Történelmi Társulat: 626–636. ISSN 0039-8098.

- Karácsonyi, János (1907). "Új adat a hód-tavi csata évéhez [New data for the Year of the Battle of Lake Hód]". Századok (in Hungarian). 41 (10). Magyar Történelmi Társulat: 948–949. ISSN 0039-8098.

- Kristó, Gyula (1981). Az Aranybullák évszázada [The Century of the Golden Bulls] (in Hungarian). Gondolat. ISBN 963-280-641-7.

- Nagy, Gyöngyi (2013). "Kun László király és a hód-tavi csata [King Ladislaus the Cuman and the Battle of Lake Hód]". A Hódmezővásárhelyi Szeremlei Társaság Évkönyve 2012 (in Hungarian). 16. Szeremlei Társaság: 69–89. ISSN 1219-7084.

- Pálóczi Horváth, András (1989). Pechenegs, Cumans, Iasians: Steppe Peoples in Medieval Hungary. Corvina. ISBN 963-13-2740-X.

- Pauler, Gyula (1899). A magyar nemzet története az Árpád-házi királyok alatt, II. [The History of the Hungarian Nation during the Árpádian Kings, Vol. 2.] (in Hungarian). Athenaeum.

- Sălăgean, Tudor (2016). Transylvania in the Second Half of the Thirteenth Century: The Rise of the Congregational System. East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages 450–1450. Vol. 37. Leiden and Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-24362-0.

- Szűcs, Jenő (2002). Az utolsó Árpádok [The Last Árpáds] (in Hungarian). Osiris Kiadó. ISBN 963-389-271-6.

- Vásáry, István (2005). Cumans and Tatars: Oriental Military in the Pre-Ottoman Balkans, 1185–1365. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83756-1.

- Zsoldos, Attila (1997). "Téténytől a Hód-tóig. Az 1279 és 1282 közötti évek politikatörténetének vázlata [From Tétény to Hód Lake: Outline of the Political History of the Years Between 1279 and 1282]". Történelmi Szemle (in Hungarian). 39 (1). Hungarian Academy of Sciences: 69–98. ISSN 0040-9634.

- Zsótér, Rózsa (1991). "Megjegyzések IV. László király itineráriumához [Remarks to the Itinerary of King Ladislaus IV]". Acta Universitatis Szegediensis. Acta Historica (in Hungarian). 92. MTA-SZTE-MOL Magyar Medievisztikai Kutatócsoport: 37–41. ISSN 0324-6965.