Southend-on-Sea

Southend-on-Sea | |

|---|---|

| Motto(s): Per Mare Per Ecclesiam (By Sea, By Church) | |

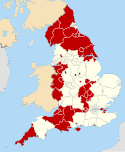

Shown within Essex | |

| Coordinates: 51°33′N 0°43′E / 51.55°N 0.71°E | |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Constituent country | England |

| Region | East of England |

| Ceremonial county | Essex |

| Admin HQ | Southend-on-Sea |

| Areas of the city | |

| Government | |

| • Type | Unitary authority |

| • Leadership | Leader & Cabinet (Labour) |

| • Governing Body | Southend-on-Sea City Council |

| • Executive | No overall control |

| • MPs | Bayo Alaba (L) David Burton-Sampson (L) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 16.12 sq mi (41.76 km2) |

| Population | |

| • Total | Ranked by District 116th 180,915 |

| • Density | 11,240/sq mi (4,341/km2) |

| Ethnicity (2021) | |

| • Ethnic groups | |

| Religion (2021) | |

| • Religion | List

|

| Time zone | UTC+0 (GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (British Summer Time) |

| Postcode | |

| Post town | southend-on-sea |

| Dialling code | 01702 |

| ISO 3166 code | GB-SOS |

| Grid reference | TQ883856 |

| ONS code | 00KF (ONS) E06000033 (GSS) |

| Website | southend |

Southend-on-Sea (/ˌsaʊθɛndɒnˈsiː/ ), commonly referred to as Southend (/saʊˈθɛnd/), is a coastal city and unitary authority area with borough status in south-eastern Essex, England. It lies on the north side of the Thames Estuary, 40 miles (64 km) east of central London. It is bordered to the north by Rochford and to the west by Castle Point. The city is one of the most densely populated places in the country outside of London. It is home to the longest pleasure pier in the world, Southend Pier,[2] while London Southend Airport is located to the north of the city centre.

Southend-on-Sea originally consisted of a few fishermen's huts and farm at the southern end of the village of Prittlewell. In the 1790s, the first buildings around what was to become the High Street of Southend were completed. In the 19th century, Southend's status as a seaside resort grew after a visit from the Princess of Wales, Caroline of Brunswick, and the construction of both the pier and railway, allowing easier access from London. From the 1960s onwards, the city declined as a holiday destination. After the 1960s, much of the city centre was developed for commerce and retail, and many original structures were lost to redevelopment. As part of its reinvention, Southend became the home of the Access credit card, due to its having one of the UK's first electronic telephone exchanges. An annual seafront airshow, which started in 1986 and featured a flypast by Concorde, used to take place each May until 2012.

On 18 October 2021, it was announced that Southend would be granted city status, in memorial to the Conservative Member of Parliament for Southend West, Sir David Amess, a long-time supporter of city status for the borough, who was murdered on 15 October 2021.[3][4] Southend was granted city status by letters patent dated 26 January 2022. On 1 March 2022, the letters patent were presented to Southend Borough Council by Charles, Prince of Wales.[5][6]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]Southend was first recorded in 1309 as Stratende, a small piece of land in the Manor of Milton (now known as Westcliff-on-Sea), within the Parish of Prittlewell.[7][8] Its next recorded mention was in a will from 1408, where the area south of Prittlewell was called Sowthende.[9] In March 1665, the British naval ship, The London, blew up while moored just of South-end on its was to fight in the Second Anglo-Dutch War.[10] The hamlet of South-end, a few fishermen's huts and Thames Farm farmhouse stayed this way until the mid 18th century, when in 1758 a large house was built, which by 1764 had become the Ship Inn.[8] The area was further developed by the building of oystermen cottages called Pleasant Row in 1767, and a year later the settlement was recorded in the parishes records for taxation purposes for the first time. The records also recorded a salt works and a lime kiln.[8] A visitor to the settlement in 1780 said "not anything in the worth place notice", but a year later the first bathing machine was brought to the hamlet.[8] By 1785, the Chelmsford Chronicle were reporting that plans were being contemplated to build a hotel with the plan to make South-end,

equal, if not rival any of the watering places to which the genteelest company usually resort; there being nothing wanted but a place of accommodation, where the agreeable distance from the metropolis, and the excellence of the roads, added to the incomparable fineness of the water, have induced so much polite company down these last two summers[8]

Nothing came of the subscription but the Chronicle reported in 1787, "Southend is likely to become a place of fashionable resort, and that there are a greater number of genteel families there this season than was ever known before".[8] By the end of the decade, the number of bathing machines had increased, the hamlet was recorded as containing the Ship Inn and 25 houses and cottages, and reported visitors such as Lord Cholmondley.[11]

The start and fail of New South-End

[edit]

In 1790, the local lord of the Manor of both Prittlewell and Milton (now Westcliff-on-Sea) and landowner Daniel Scratton set aside 35-acres of land at the top of the cliffs to the west of South-end called Grove Field and the Grove.[12] The site was split into three leasehold sites with 99 year leases, with the development called New South-End, and the original settlement being renamed Old South-end. A new road was created that cut through the development, which would later become the High Street.[12] The Chelmsford Chronicle wrote at the time,

There seems but little doubt of its becoming a place of fashionable resort, and answering the expectations of the proprietors, being only 42 miles from London and two coaches, and the post passes through it three times a week; water carriage is also convenient, being only eight hours sail, with a fair wind, from London[12]

Scratton leased the parcels of land to building firm Pratt, Watt & Louden and John Sanderson, an architect, both of Lambeth. Another site was leased from Scratton by Pratt, Watt & Louden for a brick works for the development.[12] The first house in Grove Terrace was completed by January 1792 and it was reported that the hotel had been roofed and 60 dwellings had been started on. By the summer two public houses, the Duke of York and the Duke of Clarence had opened.[12] However, by September that year The Times was reporting that the resort was likely to attract the lower and middle classes, not the wealthy clientele that was being aimed at.[12] At this time, Pratt, Watt & Louden transferred the lease to Thomas Holland, a builder and solicitor from Grays Inn, however his finances were not sound and he was soon selling off building materials.[12] By December 1792, the operators of the Duke of York, brewers Sea and Woollet closed the public house, but by September 1793 it was still in their ownership.[12] The Grand Hotel, now known as The Royal Hotel opened on the 1st July 1793, and most of Grove Terrace was available to let.[13] Later that year New South-End was listed for the first time by the parish for the annual rate, and by the summer of 1794 the Terrace, Grove Terrace, the Mews and Library had finally been completed.[12] However, by February 1795, Thomas Holland had been declared bankrupt, and the property he owned was not sold by auction until 1797, with the Heygate family purchasing the buildings. John Sanderson, the other developer was also declared bankrupt, with only Grove House built, and his estate was not sold until 1802, with much of the site still open land.[12][14] In contrast, Old South-end doubled in size during the same period including two public houses, the Ship Inn and the Anchor and Hope Inn, five shops and the Caroline baths.[15] A large house was built by Abraham Vandervord in 1792 in Old South-end which would later become the Minerva public house.[16]

Growth of the town

[edit]Due to the bad transportation links between Southend and London, there was not rapid development during the Georgian Era as there was in Brighton. Margate, although further away from London than Southend, offered cheaper boat and stagecoach fares and had more to offer the visitor.[17] Development was piecemeal in the early 19th century, with a Theatre being built in Old South-end by Thomas Trotter in 1804.[16] Southend was however mentioned in Jane Austen's novel Emma of 1815. The resort first received Royal patronage in 1801 when Princess Charlotte of Wales visited to sea bathe on the order of her physician.[18][19] Her mother, Princess Caroline of Brunswick stayed at 7-9 The Terrace during 1803, and in 1805 Lady Hamilton held a ball in the hotel assembly room in honour of Lord Nelson.[13] The visit of Princess Caroline boosted Southend's popularity with tourists.[9][20] Travellers would often arrive by sailing boat or later by Thames steamer, which presented problems as boats could only dock during high tide.[21] The Southend coast consists of mudflats that extend far from the shore, with a high tide depth that seldom exceeds 5.5 metres (18 ft). Large boats were unable to port near to the beach and no boats could approach at low tide.[22] Many potential visitors would travel beyond Southend on to Margate or other resorts with better docking facilities.[23] Due to this, local dignitaries led by the former Lord Mayor of the City of London Sir William Heygate, campaigned in the early 1820s to gain permission from parliament to build a pier.[23] On the 7 May 1829, the House of Lords passed the Bill and it received Royal Assent on the 14 May.[24][25] By July, Lord Mayor of London, Sir William Thompson laid the foundation stone, and the first section of the pier opened a year later.[24] However, Southend was still a quiet health resort, as the pier did not extend far enough out and visitors had issues disembarking.[26]

In June 1852, after several attempts at building a railway to Southend, Royal Assent was given to build the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway[27] with the line finally opening at Southend in 1856. The line had been planned to terminate opposite the pier, however residents in The Royal Terrace opposed this, and the station was built further back.[27] In 1859, the Grove Field area was leased to Sir Morton Peto, and with a consortium which included Thomas Brassey, the contractors for the railway construction, hired architects Banks & Barry to design Clifftown.[9] The first houses were made available for sale in 1871, with even the smaller properties offering a glimpse of the sea, and eventually the development would include the Clifftown Congregational Church, the Nelson Road shopping parade and Prittlewell Square, Southend's first park.[9] The arrival of the railway did not at first greatly increase visitor numbers, with Southend still being seen as quiet resort and not a noisy fashionable seaside town, with Benjamin Disraeli visiting regularly between 1833 and 1884,[28] Prince Arthur visiting in 1868, while the Empress of France, Eugénie and her son, Louis-Napoléon, Prince Imperial also came to the town.[26][19] However the growth of Southend saw a Local Board of Health be created in 1866,[29] and the large steam powered Middleton brewery was opened by Henry Luker & Co in 1869 to serve a growing population.[30][31] Southend's development as a resort however seem to stall, until the Bank Holidays Act of 1871 with holidays becoming available to more of the population.[26] The growth in visitor numbers due to the new bill saw the Local Board purchase the pier in 1873, construct Marine Parade in 1878, while the cliffs west of the pier were purchased and transformed into tree lined walkways during 1886.[32] In 1889, the Great Eastern Railway opened its station at Southend Victoria, and a new iron built replacement for the pier opened.[9][33] The town was officially incorporated in 1892, with the Local Board of Health being replaced by a municipal corporation,[29] and a year later added the on-sea to the town's name.[9] During 1892, the famous Southend department store Keddies opened its doors for the first time.[34] Between 1871 and 1901 the towns population grew 100 fold from 2,800 to 29,000.[9] Marine Park & Gardens opened during 1894, which in 1901 was redeveloped into The Kursaal amusement park.[35][36][37] In the same year, the Metropole Hotel opened on Pier Hill, which would later be renamed the Palace Hotel,[38] while the town first received both electric street lighting and trams,[39] and had fitted an electric staircase fitted by Jesse W. Reno on the site of where the current Cliff lift is.[40][41]

To celebrate Queen Victoria's diamond jubilee, a statue of her pointing out to sea was placed at the top of Pier Hill, although the locals stated she was pointing at the gents toilets![42] A foundation stone was laid by Lord Avebury in 1901 for the new Day Technical School, School of Art and Evening Class Institute with the completed building being opened by the Countess of Warwick a year later.[43][44][45][46] The site had previously been planned to be home to a new joint town hall, library and school but spiraling costs had seen the town hall and library being dropped.[47] In 1903, it was reported that around 1 million people had paid admission to use the pier, while 250,000 passengers had alighted from pleasure steamboats.[33] Further facilities were built for the growing visitor numbers, including extending the esplanade to Chalkwell in 1903,[32] and in 1909 adding the "wedding cake" bandstand at the top of the cliffs, opposite Prittlewell Square, which was one of six bandstands that stood in Southend.[48]

In 1909, an indoor roller-skating rink was opened in Warrior Square.[43] The new facilities were not only serving the growing visitor numbers, but also the residents, with the inhabitants having grown by 1911 to 62,723, the fastest growing population in England,[49] and was being regarded an Eastern suburb of London.[50] During 1913, the Day Technical School split, with the girls moving to the new Southend High School for Girls at Boston Avenue, while the day technical school was renamed Southend High School for Boys.[51][52] In 1914, the town gained county borough status, and the corporation formed the first police force.[53]

Southend during World War I

[edit]Shortly after the declaration of war, the British government began the internment of German citizens and several thousand were held on three ships, the Royal Edward, Saxonia and the Ivernia which were moored off the pier until May 1915.[54][55] The War Office selected a piece of land north of the town in 1914 for a new aerodrome, with Squadron no. 37 of the Royal Flying Corps moving in a year later.[56] Many soldiers passed through Southend en route to the Western Front. The pier was frequently used to reach troop ships, with the Admiralty stationing a war signal station at the pierhead, and Southchurch Park was taken over as an army training ground.[57][58] During the war, the public could still walk the length of the pier.[58] As the war drew on, Southend also became an evacuation point for casualties and several hotels were converted to hospitals, including the Metropole into the Queen Mary Naval Hospital.[59] Arthur Maitland Keddie, from the Keddies department store organised day trips for wounded soldiers from the Queen Mary Naval Hospital to Thundersley and Runwell.[60] The town was first bombed by German Zeppelins on 10 May 1915 with the death of one woman, while a second attack happened on the 26 May again with one death.[61][62] Another bombing raid by Gothas took place in 1917 with a further 33 deaths.[63] When peace was confirmed in 1919, official celebrations were organised by the town. A large Naval review off the Southend shore took place, with a twenty-one gun salute being fired on Peace Day on the 23 July. The town organised a carnival, fetes and a firework display.[64]

Between the wars

[edit]After the war Southend continued to grow in both residents and visitors, with many moving out of London to live in better conditions.[65] Its population in 1921 was recorded as 106,050, but as the census was postponed to the summer months due to a planned general strike, it was greatly inflated by holidaymakers.[66][67] The Corporation purchased three former German U-boat engines to generate power for the tram network, siting them at Leigh, London Road and Thorpe Bay.[68] During 1924, the Sunken Gardens at the side of the pier became Peter Pan Playground, a children's pleasure garden.[69] The pier head was enlarged in 1929 with the Prince George extension, at a cost of £58,000, to manage the increasing number of visitors arriving by paddle steamer.[70] A Southend icon, EKCO, opened their large factory at Priory Crescent on the site of a former cabbage patch in 1930.[71] To cope with the increase demand for housing, estates like Earls Hall were built during 1930, with the Manners Way estate joining it just north along with a new road towards in Rochford in 1937.[72] The London Taxi Drivers Charity for Children completed their first taxi drive to Southend in 1931, with 40 Hackney Carriages bringing children to the town, who were given 6d to spend on the seafront.[73] At the 1931 Census the population of Southend was recorded at 110,790,[74] however the town would grow further by absorbing South Shoebury district and parts of Rochford district in 1933. Southend tried their first autumn illuminations during 1935, following the example set in 1913 by Blackpool.[43] The town became a favourite with motorcycle riders during the 1930s, with the phase, Promenade Percy, coming from this pastime.[75] In the same year, the council purchased land on the Cliffs at Westcliff to build a 500 seater theatre and concert venue to be called Shorefield Pavilion with working starting four years later only to be suspended by the start of the war.[76][77]

Southend during World War II

[edit]Southend became an essential part of the British war machine.[78][79] In 1939, the Royal Navy had commandeered Southend Pier, renaming it HMS Leigh,[80] with the army building a concrete platform on the Prince George extension to house anti-aircraft guns. The navy also took over the Royal Terrace for its personnel.[81] The pier was used by the navy to help control the River Thames, along with the Thames Estuary boom that was built at Shoebury Garrison during 1939, and organised over 3,000 East Coast convoys by the end of the war.[82][83][84] HMS Leigh was attacked by the Germans on the 22 November when they dropped magnetic mines and machine gunned the pier, but none of the mines caused any damage and the navy's anti-aircraft guns destroyed one of the German planes. It was the last time there was a concentrated attack on the pier.[85] Southend Airport was requisitioned by the RAF at the outbreak of war, becoming a satellite of Hornchurch and being renamed RAF Rochford.[86] The town was believed to be the most heavily defended place in Essex, ranging from three and half miles of anti-tank cubes on the seafront, machine gun and anti-aircraft posts, road blocks and barrage balloons.[79][87]

On 31 May 1940, six cockle fishing boats: the Endeavour, Letitia, Defender, Reliance, Renown and the Resolute were joined by the Southend lifeboat Greater London at the pier on their way to assist at the Dunkirk evacuation.[88][89] The town itself was first hit by German bombing in May 1940, when the Nore Yacht club was hit while 10 soldiers were killed near the airport.[90] Southend High School for Boys was hit in a raid in June 1940.[90] By June 1940, much of the town was sealed off, with all bar 10% of the population that were engaged in essential services, evacuated and only military personnel remaining.[91] A cordon of 20 miles was set up, with the town being designated part of the coastal defence area, but with the risk of invasion dropping, in 1941 it was reduced to 10 miles.[87][92] By 28 October 1940, RAF Rochford had been renamed RAF Southend, no longer being a satellite of Hornchurch, although they still had Fighter Control at the base. A day later 264 Squadron arrived for night fighter duties equipped with the Boulton Paul Defiant.[93] In the same month, a bombing raid damaged houses in the Fleetwood Avenue in Westcliff.[90] During 1941, Prime Minister Winston Churchill visited Shoebury Garrison twice for weapon demonstrations, with the Experimental Establishment carrying out numerous trials of weird and wonderful weapons.[94] An air raid in February 1941 destroyed the London Hotel in the High Street,[95] while the foreshore was often used by German bomber aircraft as a dumping ground for their bomb loads during the war if their primary target was not possible to hit.[96]

In 1942, the area along the seafront from the Pier to Chalkwell was transformed into HMS Westcliff, a huge naval transit and training camp run by Combined Operations.[97][98] The police helped the Combined Operations Service find the owners of the empty properties so they could requisition properties to billet their staff.[97] HMS Westcliff was officially opened, in secret, by Lord Mountbatten in 1943.[98] The well known jeweller R.A. Jones store was damaged by bombing in October 1942.[99] An amusing moment during the war was Lord Haw-Haw announcing in his radio broadcasts that German forces had sunk the British ships HMS Westcliff and HMS Leigh.[97] The town started to fall under constant V1 and V2 rocket attacks until December 1944, with one hitting the Pavilion on the pier.[100][101] In 1944, while towing a Mulberry harbour caisson to Goole in Hampshire, it was found to be leaking so it was brought into the Thames Estuary off Thorpe Bay to be checked, but after being left by the tugs, it moved partially into the channel, and without support of the mudflat snapped in half and remains there to this day.[102] Further disaster happened when in August 1944, the liberty ship SS Richard Montgomery, with over 6,000 tonnes of explosive on board, lost its mooring off the Isle of Sheppey, opposite Southend, in strong winds and wedged itself onto the mudflat, breaking its back.[103] Prior to this, HMS Leigh had been the mustering point for 576 ships in June 1944 before they headed for Normandy and D-Day.[104] Force L, the follow up forces that were to follow the initial D-Day invasion force were located at Southend.[105]

Decline and regeneration

[edit]After the war Southend soon opened up to visitors again, with pier officially being given permission to open by the Home Office in March 1945, although the Prince George Extension was still out of bounds to the public. The Chelmsford Chronicle reported that the public returned in their droves, with 79,000 visitors turning up in the first nineteen days, though it wasn't until 30 September that the pier was officially derequisitioned by the Navy.[106] The town, which had been heavily fortified, slowly started to remove the defences during 1945, however the dust and noise attracted unhappiness with the holidaymakers, with two elderly ladies complaining to the police that it should be stopped while they were on their vacation for the week. Many of the fairground attractions only opened at weekend due many of the men who worked them still being enlisted.[107] It wasn't until 1946 that the town started to return to normal,[106] and by 1949-50 visitor numbers had returned with over 5.75 million visiting the pier alone.[108] The visitors would have used the replaced pier railway, newly installed in 1949,[109] or may have visited the newly opened Golden Hind replica containing waxworks by Louis Tussaud next to the pier.[110][106] These numbers grew to a peak of 7 million the following year.[111]

Southend would use the Kursaal and Pier as nodal attractions to promote the town to tourists during the 50s and 60s.[112] On 31 January 1953, Southend seafront was affected by the North Sea flood, with Peter Pan's Playground left underwater. However the town was not affected as badly as other parts of Essex.[113] The town however was more joyous in June, with the town holding a week of celebrations to commemorate the Coronation of Elizabeth II. This included an air race at the airport featuring aerobatic displays by supersonic jets, a military tattoo, a coronation ball at the Kursaal featuring Ted Heath and his Music and a grand fireworks display on the seafront.[114] In 1956, the Great Eastern line was electrified[115] which encouraged more Londoners move to the town, further making it into a dormitory town for the capital.[116] On 14 April 1955, Air Charter inaugurated its first vehicle ferry service between Southend and Calais using a Bristol 170 Mark 32 Super Freighter.[117] It was the sign of the future for tourism in the town, with the British public moving from UK holidays to foreign vacations that saw the start of the downturn on for the British seaside towns,[118] though Southend still had strong numbers visiting.[119]

Between 1948 and 1962, it was recorded that 22% of the town's population were working in holiday related industries.[120] The council were concerned that the town was to reliant on tourism and being a dormitory town, that they decided to try and grow the commercial industry in the town, which coincided with plans in central government to de-centralise services.[121][122] The Miles Report of 1944 had already identified Victoria Avenue as the perfect location for office development,[123] and the council in 1960 finally started work on a new Civic Centre on land previously purchased to build a new further education college.[124] The Civic Centre would encompass a new police station that opened in 1962, a courthouse in 1966, council offices and chamber in 1967, a new College in 1971 and a Library in 1974. The planned fire station was dropped and was eventually built in Sutton Road. These replaced cramped facilities located in Alexandra Road and Clarence Street.[125] The council in 1960 put forward a redevelopment plan, called Prospect of Southend to central government, to improve both the commercial and retail growth in the town, but the original plan and an amendment, which requested compulsory purchase orders, were both rejected by the Minister for Housing Development and Local Government.[126][127][128][129] Part of the plans included redeveloping the area north of the High Street, which included the Talza and Victoria Arcades, had been discussed with developer Hammerson. Although the plans were rejected by central government, Hammerson started a programme of buying property in the area, and in 1964 the council accepted Hammerson's plans for the site. Hammerson had by this point had purchased 93% of the freeholds, with the council using Section 4 of the Town and Country Act 1962 to compulsory purchase the remaining properties.[128] The development, which became Victoria Circus Shopping Centre, opened in 1970 and saw a large area of much loved Southend demolished.[128][130]

Further developments put forward by the council included building a ring road around the town centre. First discussed by the council in 1955,[131] plans were started to be developed in 1961, with the electrification of the London, Tilbury and Southend railway line acting as impetus as bridges over the line which were on the route of the planned ring road needed replacing.[131][132] In 1965, the Ministry of Transport gave the council a grant of £869,986 to the planned cost of £1.2 million to build the North and East sections of the ring road.[133] The council used compulsory purchase orders to buy up many of the properties along the planned route and work started in 1966,[132] with the first section opening in 1967 with the first high pressure sodium street lamps in Britain.[134] The West and South sections of the ring road were never completed.[135] In the same year, work was started on dualing Victoria Avenue to Carnarvon Road,[136] while part of the High Street was pedestrianised by 1968.[137] By this point Victoria Avenue had seen further development, with offices opening along the section opposite the Civic Centre including Portcullis House in 1966, the first offices opened by HM Customs and Excise in the town.[138][139]

In 1969, Southend-on-Sea Borough Police amalgamated with Essex Constabulary to become the Essex and Southend-on-Sea Joint Constabulary. This merger was campaigned against by the council and the local MPs.[140] The town's decline as a holiday resort continued, with the visitor numbers on the pier falling to a million during 1969-70 and the attraction lost £45,000.[108] The town saw the number of visitors had fallen from the 1950s by 73%, which was against the backdrop of more Brits travelling abroad, growing from just 1.5 million holidays in 1951, to 4.2 million by 1971.[118][141] The pier slowly began to decline and with it the structure began to deteriorate. In 1971, a child's injury prompted a survey, leading to repairs and replacement to much of the pier railway throughout the decade.[142] In response, the council allocated £370,000 over two years, starting in 1972, to ensure the pier remained maintained,[143] however the pier head burnt down in 1976 and in 1978 the pier railway was closed due to its poor condition.[144] Prior to the pier railway closure, the Kursaal closed the majority of the amusement park in 1973.[145]

The town became one of the earliest to receive an electronic telephone exchange in 1971,[146] and by 1972 Access, Britain's second credit card, opened their offices in the former EKCO site in Priory Crescent.[147][148] A year later HM Customs and Excise opened the central offices for the collection of VAT.[149] In 1972, Southend Air Museum opened its doors for the first time at Aviation Way.[150] This was against the backdrop of the government planning to build a new airport on Maplin Sands at Foulness Island, which the council purchased a share in the consortium of developers hoping to shape the benefits for the town,[151] but the airport plans were pulled by the new Labour government in 1974.[152] During 1976, plans called Prospects 1976 was released to improve the town's ability to attract holidaymakers, including bastions with facilities at Chalkwell and Westcliff, but they never got off the drawing board.[153]

In 1980, the town's reinvention as a commercial centre had seen it shrug off its tag as a dormitory town for London,[154] however the future of the pier was in doubt and a campaign, which included Sir John Betjeman, pushed the council to keep the pier open.[155][156] The pier may have been saved, now run by Lecorgne Amusements,[157] but the town lost another attraction in 1983, when the Southend Aircraft Museum closed for the final time.[158] However in the same year the council put up £800,000 with the Historic Buildings Fund investing £200,000 in restoring the pier.[157] Further invest saw a new narrow gauge railway fitted to the pier, which was reopened by Princess Anne on 2 May 1986.[159] A contract was given to Brent Walker to run the pier in 1986,[160] but in September of that year it was damaged by the ship Kings Abbey, destroying the lifeboat station.[157] Two years later, management of the pier returned to the council.[161] The seafront would see several plans put forward in the late 70s and the 1980s to build a marina on the seafront by numerous developers including Brent Walker, including an artificial island alongside the pier, though the council ended the plans after they were objected to by the RSPB due to loss of intertidal areas for wildlife was deemed to much.[162][163][164][165] Plans were resurrected again in 2020 for a marina off the coast at Shoeburyness.[166] In May 1986, the Southend Airshow was started, featuring a fly past by Concorde, and after the first year where entry was charged by the council, it would grow to become Europe's biggest free airshow.[167] The final show took place on 2012, with the council announcing in January 2013 it could no longer afford to run the show.[168] An attempt to revive the show for September 2015, as the Southend Airshow and Military Festival, failed.[169]

The town started to regenerate its visitor attractions, with the Sealife Centre opening in 1993.[170] In 1995, the owners of Peter Pan's Playground purchased the land East of the pier and started to expand, creating Adventure Island,[171] being rated best-value amusement park in Britain in 2024.[172] The Kursaal, was purchased by Brent Walker in 1988 with plans to redevelop the site as a water theme park, but the company entered liquidation and the site remained empty.[173] The council purchased the Kursaal, and after a multimillion-pound redevelopment by the Rowallan Group, the main Kursaal building was reopened in 1998 with a bowling alley, a casino and other amusements.[174][173] In 2003, during excavations for a road widening scheme at Priory Crescent, an Anglo-Saxon royal burial was found dating from the 6th century, with a display of the finds displayed at Southend Central Museum since 2019.[175][176] The road widening was cancelled after a campaign known as Camp Bling. A year earlier there was a slippage on the Cliffs, which saw the bandstand close. The cliffs were stabilised in 2013, with the council planning to build a new museum at the location to host the Anglo Saxon discoveries, as well as the Central Museum and Beecroft Art Gallery, but in 2018 it was abandoned due to rising costs.[177] The town's commercial growth during the 60s and 70s, declined with the departure of many of their former tenants, including HM Revenue and Customs in 2022, and many of the former offices have been converted to apartments.[178][179][180][181]

The formation of the city

[edit]On 15 October 2021, the Member of Parliament for Southend West, Sir David Amess, was fatally stabbed during a constituency meeting in Leigh-on-Sea. On 18 October 2021, the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, announced that the Queen had agreed to grant Southend-on-Sea with city status as a memorial to Amess, who had long campaigned for this status to be granted.[3] Preparations, led by Amess, for Southend to enter a competition for city status in 2022 as part of the Queen's Platinum Jubilee were underway at the time of his death.[182][183] A "City Week" was held throughout the town between 13 and 20 February 2022,[184] beginning with the inaugural "He Built This City" concert named in honour of Amess.[185][186] The concert was held at the Cliffs Pavilion and included performers such as Digby Fairweather, Lee Mead, and Leanne Jarvis.[187] Other events such as a city ceremony and the Southend LuminoCity Festival of Light were held during the week. Sam Duckworth, who knew Amess personally, performed at some of the events.[186] On 1 March, Southend Borough Council was presented letters patent from the Queen, by Charles, Prince of Wales, officially granting the borough city status.[5] Southend became the second city in the ceremonial county of Essex, after Chelmsford, which was granted city status in 2012.[188]

Geology

[edit]The seven kilometres of cliffs from Hadleigh Castle to Southend Pier consist of London Clay overlaid in the Ice age by sand, gravel and river alluvium.[189] The cliffs have been affected by slip planes affected by groundwater, with major slips having occurred in 1956, 1962, 1964 and 1969.[190] In 2001, a small slippage occurred, which was followed by a major slippage in November 2002, which irreparably damaged the cliffs bandstand and restaurant. At a later date, a report came to light from a month before the slip which showed there was already signs of a slippage.[190] A £2.8 million cliffs stabilisation programme was completed in 2013.[191] In May 2023, work started to investigate further slippage at Belton Hills in Leigh-on-Sea, with remedy work said to cost £500,000.[192][193]

The British Geological Survey provided a summary in 1986 of the geology of the country around Southend and Foulness:[194]

Geological succession

[edit]| Recent and Pleistocene | Description |

|---|---|

| Made Ground | Urban refuse, rock debris etc |

| Blown sand | Sands with shell debris overlying beach gravels |

| Alluvium and tidal flat deposits | Soft greyish brown clays and silty sands with subordinate peat. Shell banks north of the River Crouch |

| River Terrace Deposits: Loam and Sand and Gravel | Yellow-brown sandy silts, locally calcareous in the lower part and sandy gravels with seams of silt and clay |

| Head | Firm brown sandy clay or loam with clayey gravel intercalations |

| Brickearth | Yellow-brown clayey silts, locally calcareous in the lower part |

| Sand and gravel of unknown age | Sand and gravel with variable clay content |

| Boulder Clay | Unsorted stony clays |

| Glacial Sand and Gravel | Sand and gravel with seams of silt and clay |

| Buried Channel Deposits––(not exposed at surface) | Grey laminated clays with subordinate sands, overlying silty sands with gravels |

Solid Formations

[edit]| Palaeocene and Eocene | Description | Thickness |

|---|---|---|

| Bagshot Pebble Bed | Rounded black flint pebbles in a sandy matrix | up to 4 |

| Bagshot Beds | Orange-brown fine-grained sands with subordinate silt and clay beds | up to 23 |

| Claygate Beds | Brown and orange-brown interbedded fine-grained sands, sandy silts, clayey silts and silty clays | 17 to 23 |

| London Clay | Grey (unweathered) and brown (weathered) fine-grained sandy clays, and silty clays | 125 to 135 |

| Woolwich Beds including Oldhaven Beds | Yellowish orange fine- and medium-grained sands with subordinate grey clays and pebble beds | up to 15 |

| Thanet Beds | Buff fine-grained sands | up to 40 |

| Cretaceous | Description | Thickness |

|---|---|---|

| Upper Chalk | White chalk with abundant flint horizons | about 85 |

| Middle Chalk | White chalk with occasional flint horizons | about 70 |

| Lower Chalk | Grey chalk with marls | about 50 |

| Upper Greensand | Calcareous sandstone | 4 to 9 |

| Gault | Dark greenish grey calcareous mudstones (with local basal white sand) | 34 to 56 |

Governance

[edit]Current administration

[edit]Southend is governed by Southend-on-Sea City Council, which is a unitary authority, performing the functions of both a county and district council. There is one civil parish within the city at Leigh-on-Sea, which has a Town Council that was established in 1996.[195] The rest of the city is an unparished area.[196][197] The city is split into seventeen wards, with each ward returning three councillors. The 51 councillors serve four years and one third of the council is elected each year, followed by one year without election.[198] As of the 2024 local elections a coalition led by Labour run the council.[199]

Administrative history

[edit]Southend's first elected council was a local board, which held its first meeting on 29 August 1866.[200] Prior to that the town was administered by the vestry for the wider parish of Prittlewell. The local board district was enlarged in 1877 to cover the whole parish of Prittlewell.[201]

The town was made a municipal borough in 1892. In 1897 the borough was enlarged to also include the neighbouring parish of Southchurch,[202] with further enlargement in 1913 by taking over the area formerly controlled by Leigh-on-Sea Urban District Council.[203] In 1914 the enlarged Southend became a county borough making it independent from Essex County Council and a single-tier of local government.[53] The county borough was enlarged in 1933 by the former area of Shoeburyness Urban District and part of Rochford Rural District.[204]

Southend Civic Centre was designed by borough architect, Patrick Burridge, and officially opened by the Queen Mother on 31 October 1967.[205]

On 1 April 1974, under the Local Government Act 1972, Southend became a district of Essex, with the county council once more providing county-level services to the town. In 1990, Southend was the first local authority to outsource its municipal waste collection to a commercial provider.[206] However, in 1998 it again became the single tier of local government when it became a unitary authority.[207]

Upon receiving city status on 1 March 2022, the council voted to rename itself 'Southend-on-Sea City Council'.[5]

Coat of Arms and Twinning

[edit]The Latin motto, 'Per Mare Per Ecclesiam', emblazoned on the municipal coat of arms, translates as 'By [the] Sea, By [the] Church', reflecting Southend's position between the church at Prittlewell and the sea as in the Thames estuary. The city has been twinned with the resort of Sopot in Poland since 1999[208] and has been developing three-way associations with Lake Worth Beach, Florida.

Members of Parliament

[edit]Current MPs

[edit]Due to boundary changes, the seats in Southend changed at the 2024 election to Southend East and Rochford[209] and Southend West and Leigh.[210]

In the 2024 United Kingdom general election, Bayo Alaba of Labour won 38.8% of the vote to win the seat of Southend East and Rochford, with a 57% turnout.[211] The new MP for Southend West and Leigh is David Burton-Sampson of Labour, who won 35.6% of the vote on a turnover of 63%.[212] This was the first time since the initial seat in parliament was created in 1918, that Labour have been elected, as the city had previously been held by the Conservatives.[213]

Former MPs

[edit]From the creation of the first Member of Parliament seat for Southend in 1918, there has been a history of long serving MPs. Rupert Guinness of the Guinness family was Southend's first MP, and only stepped down when he was given a peerage. His wife, Gwendolen Guinness replaced him in 1927, until she retired and her son-in-law Henry Channon replaced her in 1935, serving until his death in 1958.[214] Because of the Guinness connection, the seat became known in the media as "Guinness-on-Sea".[215]

In 1950, the one seat was split into two, Southend East and Southend West due to the growth in the town.

Sir Stephen McAdden served as the MP for Southend East from 1950 until his death in 1979.[216] His replacement Sir Teddy Taylor served Southend East, then its replacement seat Rochford and Southend East from 1980 until he retired in 2005.[217] James Duddridge served as Sir Teddy's replacement from 2005 until stepping down at the 2024 election.[218]

Paul Channon, son of Henry replaced his father as the MP for Southend West from 1959 until he stepped down in 1997.[219] He was replaced by Sir David Amess, who served from 1997 until his murder in 2021. Anna Firth of the Conservatives had replaced Amess at the by-election in January 2022 with 86% of the vote but lost her seat at the 2024 election.[220][221][222][223]

Demography

[edit]Population density

[edit]Southend is the seventh most densely populated area in the United Kingdom outside of the London Boroughs, with 38.8 people per hectare compared to a national average of 3.77.[224]

Greater Urban Area

[edit]

The greater urban area of Southend spills outside of the borough boundaries into the neighbouring Castle Point and Rochford districts, including the towns of Hadleigh, Benfleet, Rayleigh and Rochford, as well as the villages of Hockley and Hullbridge. According to the 2011 census, it had a population of 295,310.[225]

Deprivation

[edit]Save the Children's research data shows that for 2008–09, Southend had 4,000 children living in poverty, a rate of 12%, the same as Thurrock, but above the 11% child poverty rate of Essex as a whole.[226]

The Department for Communities and Local Government's 2010 Indices of Multiple Deprivation Deprivation Indices data showed that Southend is one of Essex's most deprived areas. Out of 32,482 Lower Super Output Areas in England, area 014D in the Kursaal ward is 99th, area 015B in Milton ward is 108th, area 010A in Victoria ward is 542nd, and area 009D in Southchurch ward is 995th, as well as an additional 5 areas all within the top 10% most deprived areas in England (with the most deprived area having a rank of 1 and the least deprived a rank of 32,482).[227] Victoria and Milton wards have the highest proportion of ethnic minority residents – at the 2011 Census these figures were 24.2% and 26.5% respectively. Southend has the highest percentage of residents receiving housing benefits (19%) and the third highest percentage of residents receiving council tax benefits in Essex.

Employment and unemployment

[edit]As of May 2024, The Office of National Statistics have recorded the following employment, unemployment and economic inactivity in Southend-on-Sea.[228]

| Area Recorded | Southend - Current (%) | East of England Rate - Current (%) | Southend - Previous Year (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employment rate (16-64 year olds) | 75.6 (December 2023) | 78.3 | 75.7 |

| Unemployment rate (16 years +) | 5.2 (December 2023) | 3.6 | 2.9 |

| Claimant Count (16-64 year olds) | 4.5 (March 2024) | Not provided | 4.3 |

| Economic inactivity (16-64 year olds) | 21 (December 2023) | 19.4 | 23 |

In the 2021 census, it was reported that 69.1% of the working population work in full-time employment, with 10.9% working more than 48 hours a week.[1]

Population statistics

[edit]As of the 2021 census, the population was recorded as 180,686, with 51.3% of the population being female, and 48.7% recorded as male.[1]

The following table shows the breakdown of the population by age:[1]

| Age Group | No. | % of the population. |

|---|---|---|

| Aged 4 years and under | 10,242 | 5.7 |

| Aged 5 to 9 years | 10,899 | 6.0 |

| Aged 10 to 15 years | 13,135 | 7.3 |

| Aged 16 to 19 years | 7,201 | 4.0 |

| Aged 20 to 24 years | 9,356 | 5.2 |

| Aged 25 to 34 years | 23,158 | 12.8 |

| Aged 35 to 49 years | 36,681 | 20.3 |

| Aged 50 to 64 years | 35,453 | 19.6 |

| Aged 65 to 74 years | 18,023 | 10.0 |

| Aged 75 to 84 years | 11,560 | 6.4 |

| Aged 85 years and over | 11,560 | 2.8 |

In the census it was reported that 87.5% of the population were born in the UK, while for those who were born outside of the country, most were born in Europe, and most had lived in the UK for more than 10 years. The census reported that nearly 33,000 of the population were retired.[1]

A fifth of the working population commutes to London daily. Wages for jobs based in Southend were the second lowest among UK cities in 2015. It also has the fourth-highest proportion of people aged over 65. This creates considerable pressure on the housing market. It is the 11th most expensive place to live in Britain.[229]

Economy

[edit]Current industry

[edit]Tourism is still a key industry in Southend, with over 7,500 employed people in the sector, which counts as 15.9% of jobs in the city.[230] In 2019, it was reported that 253,900 people had stayed, generating £53.4 million while over 7.3 million day visitors had contributed over £308 million to the economy.[230] Rossi's Ice-cream is a famous Southend institution, having existed since 1932.[231]

Aerospace is another key industry.[232] Southend is one of EasyJet's 10 bases in the UK.[233] In addition to flights, Southend has several aircraft maintenance firms including Inflite MRO Services,[234] and in Ipeco, have a former London Stock Exchange listed international aircraft seat and airframe manufacturer headquartered in the city since 1960.[235][236][237] In 2024, Ipeco was awarded The King's Awards for Enterprise for promoting opportunity.[238]

Other manufacturing companies based in Southend include MK Electric, who relocated there in 1961 and in 2014 had seen the 100 millionth socket made at the factory,[239] and Olympus UK & Ireland (formerly Keymed), who specialise in medical equipment and have been in Southend since 1969.[240][241][242]

Another major employment area in Southend is Financial Services, with NatWest's credit card operations located in Thanet Grange.[232][243][244] In 2006, travel insurance company InsureandGo relocated its offices from Braintree to Maitland House in Southend-on-Sea. The company brought 120 existing jobs from Braintree and announced the intention to create more in the future.[245] However the business announced the plan to relocate to Bristol in 2016.[246] The company however as of 2021 is still located in Southend.[247] The building is now also home to Ventrica, a customer service outsourcing company.[248][249]

Southend has industrial parks located at Progress Road, Comet and Aviation Way in Eastwood and Stock Road in Sutton. Firms located in Southend include Hi-Tec Sports.[250]

As of 2023, large employers (those employing more than 250 people) made up only 0.4% of companies within the city, while micro employers (9 or less employees) make up 90.8%, which is 1.2% greater than the East of England average.[251]

Former notable industry

[edit]-

Former EcoMold factory

-

Former HMRC office at Alexandra House

-

British Air Ferries Carvair at Southend Airport

EKCO was an electronics manufacturer formed by local, Eric Kirkham Cole in 1926.[252] The business started at factory in Leigh-on-Sea, before opening a larger site at Priory Crescent in 1930.[71] The company expanded from radio production into televisions, radar and plastics, and employed over 8,000 people in Southend at its height.[71] In 1960, EKCO merged with Pye to form British Electronic Industries Ltd, but due to several financial issues, the television and radio manufacturing on the site was closed in 1966 with the loss of 800 jobs.[147] Pye of Cambridge (British Electronic Industries was renamed in 1963) was purchased by Philips in 1967. The offices and radio factory was sold to the Joint Credit Card Company in 1972, however EKCO Plastics continued to operate from the site.[147] EKCO Plastics had been a separate subsidiary, and had won awards from the Design Council and the Duke of Edinburgh for their products.[253] Pye sold Ekco Plastics to National Plastics, a subsidiary of Courtaulds, in 1978.[254][255][256] Linpac purchased National Plastics subsidiary NP Ekco in 1986.[257][258] Linpac became Ecomold, but closed the factory after it fell into administration in 2008.[259] After the Ecomold factory closed, the whole site was converted into Ekco Park, a 231 home estate.[260] A statue of Eric Cole was placed in his honour on the estate during 2020.[261]

The Joint Credit Card Company was created by Lloyds Bank, Midland Bank and National Westminster Bank, and operated as the Access credit card.[148] It was the second credit card company launched in the UK, becoming available during 1972. The company purchased the former EKCO television and radio factory on Priory Crescent from owners Philips to operate from.[147] The company would expand by opening further offices across the city. In 1989, the company was renamed as Signet Ltd in 1989, along with a change to allow member banks to process their own customers as part of a Competition and Monopolies Commission review into credit cards.[262] In the same year, processing was transferred to a new site in Basildon,[263][264] while offices across Southend were transferred to the member banks. This included Esplanade House to NatWest,[265] Chartwell House to Midland Bank/HSBC[266] and Essex House to Lloyds Bank.[267] In 1991, the business was sold to First Data Resources,[268] and the Priory Crescent site was sold to Royal Bank of Scotland. The credit card industry in Southend declined with HSBC closing their operations in 2011,[269] while Lloyds Bank joined them by closing Essex House in 2013.[270] Royal Bank of Scotland/NatWest however stayed, and moved to a new purpose built building at Thanet Grange in 2003.[271]

C. E. Heath moved to Southend during 1966 into the purpose built Heath House on Victoria Avenue. C. E. Heath was one of the largest insurance brokers in the world. The company also operated offices in Sutton Road and had a social club in Wellstead Gardens. In 1996, redundancies saw the number of staff drop from 600 to 300. However six years later, C. E. Heath merged with Lambert Fenchurch Group and announced closure of the Southend office.[272][273] The property remained empty until 2016 when it was converted into flats.[274]

HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) previously employed over 4,000 people in Southend in Alexandra House and Portcullis House, which sat side by side on Victoria Avenue, and Tylers House/Dencora Court, Tylers Avenue.[275] A training centre was located in Carby House, also in Victoria Avenue.[276] In 2008, it was announced that both Tylers House and Portcullis House would be surplus to requirements.[277] Tylers House would close, with the space rented out by HMRC to other government departments.[278] HMRC announced in 2015 that they would be closing its Southend office and transferring the operations to Stratford.[279] Portcullis House closed first in 2008, and in 2019 the site was purchased by Weston Homes to develop into 217 flats.[280][281] Alexandra House has since closed and in late 2023 planning permission was being sought to convert the building into 557 flats by Comer Group.[282]

Flightline was an airline, maintenance and aircraft sales company that operated out of London Southend Airport, which went into administration in 2008.[283][284]

ATC Lasham was an aircraft maintenance company based out of both Southend and Southampton airports. It collapsed in 2015 with the loss of 144 jobs.[285]

British Air Ferries was an airline that from 1967 was headquartered at Southend Airport.[286] The company went into administration, and after several changes of ownership became British World Airlines in 1993, however the business entered administration for a final time in 2001.[287]

Jota Aviation was a specialist air haulage company working in the motorsport industry and based at London Southend Airport since 2009. The company ceased operations in 2022.[288][289][290]

Essex Furniture plc was a furniture manufacturer and retailer that was based in Southend that first listed on the Unlisted Securities Market of the London Stock Exchange in 1989.[291] The business operated five stores under the Essex Furniture brand within Essex, and expanded nationally to 28 stores under The Furniture Workshop nameplate.[292] In 1998, the company experienced financial difficulties, closing their Southend factory before their shares being suspended on the London Stock Exchange, announcing a £3.7 million loss in the first half of 1998.[293] The company entered insolvency later that year.[294]

Utilities history

[edit]Electricity

[edit]Southend-on-Sea County Borough Corporation provided the borough with electricity from the early twentieth century up to 1966 from the Southend power station in London Road. Upon nationalisation of the electricity industry in 1948, ownership passed to the British Electricity Authority and later to the Central Electricity Generating Board. Electricity connections to the national grid rendered the 5.75 megawatt (MW) power station redundant. Electricity was generated by diesel engines and by steam obtained from the exhaust gases. The power station closed in 1966 and in its final year of operation it delivered 2,720 MWh of electricity to the borough.[295]

Gas

[edit]In 1853, a new company, Southend Gas Company, was set up to build a coal gas works to supply Southend.[296] The works opened on Eastern Esplanade in 1855, and helped with the development of the then fledgling town.[297][298] The company was purchased by Southend Corporation after the First World War,[299] with its own landing pier locally known as Southend Pier Junior.[298] The company was nationalised in 1949 and was transferred to the North Thames Gas Board,[300] who in 1960 added the brutalist Esplanade House to the site as offices. The site stopped producing coal gas in 1968, and the works was demolished.[297] Esplanade House, was taken over by Access credit card operations in the 1980s, but by the 1990s they had moved out and the gas works site remained empty until it was demolished to make way for a Premier Inn in 2014.[301][302]

Water

[edit]Southend Waterworks Company was formed by Thomas Brassey in 1865, initially to provide water for the steam engines on the new railway line that opened in 1856, and to which Brassey was involved with. The company constructed the city's first deep borehole in Milton Road, which would be known as Southend No.1 Well, along with a reservoir to hold 300,000 gallons.[303] In 1870, Brassey died, and a limited company was formed to take over the works. In 1879, the Southend Water Bill was passed to incorporate the company to allow it to raise the necessary cash to expand the supply to the growing town, and to be able to charge rates per home based on the properties value.[304] The company created further boreholes in and around Southend, including Vange, where a treatment works was built to soften the water from the five boreholes located in Vange and Fobbing, with a first of its kind lime recovery plant.[303] During 1896, the water supply was tested due to a rising issue with Typhoid fever in the town. The investigation, led by Dr. R. Bruce Low, concluded that the water quality was good, but it was poor sanitation, with issues with the identified with the town's sewer system and discharge onto the beach. The sewer system had been found to be wanting at a previous investigation in 1890 by Dr Thresh, and the town council was investing £35,000 to upgrade and improve the sewers.[305] In 1907, the company's boundaries were extended by the government to incorporate the areas of both Leigh on Sea Urban District Council and Billericay Rural District Council.[306]

By 1920, the limit had been meet by how much water could be extracted from the boreholes in the chalk, and in 1921 a joint application with neighbouring water firm South Essex Waterworks was raised to extract water from the River Chelmer and the River Blackwater at Langford.[307][303] That scheme was rejected, but a further application resulted in the Southend Waterworks Act of 1924 which was passed by parliament allowed the company to extract river water at Langford.[303][308] The supply at Langford was pumped to reservoirs built at Oakwood on the Belfairs/Daws Heath border.[303] In the late 1940s, both Southend Waterworks Company and South Essex Waterworks jointly planned a new large reservoir in the Sandon Valley, south of Chelmsford. Work started in 1951, which included the demolition of the hamlet of Peasdown near South Hanningfield. Hanningfield Reservoir opened in 1957 at a cost of £6 million.[309] In 1970, the Essex Water Order was passed by parliament which saw Southend Waterworks Company and South Essex Waterworks merge to create the Essex Water Company.[310][311] The company became Essex and Suffolk Water in 1994.

Retail

[edit]

Southend High Street runs from the top of Pier Hill in the South, to Victoria Circus in the north. It currently has two shopping centres. The Victoria (built during the 1960s and a replacement for the old Talza Arcade, Victoria Arcade and Broadway Market) is located at the north end of the High Street.[312] The Royals Shopping Centre is located at the south end of the High Street, was designed by the Building Design Partnership, with construction starting in 1985.[313][314] The centre was officially opened in March 1988 by singer-actor Jason Donovan. The centre replaced the south end of High Street and Grove Road, and saw the demolition of the Ritz Cinema and Grand Pier Hotel.[315] Prior to the opening, Morrissey filmed the video for his top ten charting track Everyday Is Like Sunday in the centre.[316] Southend High Street mainly consists of chain stores, with Boots located in the Royals, while Next anchor the Victoria.[317] However, since the covid pandemic the amount of empty shops in the city centre has increased greatly, with the High Street being called a ghost town.[318][319][320]

A business that started in Southend during 1937 and is still active in 2024 is Dixons Retail, now renamed Currys plc.[321]

The city of Southend has shopping in other areas. The Broadway in Leigh-on-Sea is known for its independent boutiques and coffee shops.[322] Leigh Road in Leigh-on-Sea, Southchurch Road and London Road are where many of Southend's independent businesses now reside.[323] Hamlet Court Road, Westcliff-on-Sea was once known as the Bond Street of Essex,[324] and is full of historical buildings, having been made into a conservation area in 2021.[325] The road hosts the In Harmony festival each year.[326]

There are regular vintage fairs and markets in Southend, held at a variety of locations including the Leigh Community Centre and Garon Park.[327] A record fair is frequently held at West Leigh Schools in Leigh on Sea.[328]

York Road Market

[edit]Demolition of the historic Victorian covered York Road market began on 23 April 2010,[329] with the site becoming a car park. A temporary market had been held there every Friday until 2012 after the closure of the former Southend market at the rear of the Odeon.[330] As of 2013, a market started to be held in the High Street every Thursday with over 30 stalls, with a further Saturday market being started in 2023.[331][332]

Former retail businesses

[edit]-

R A Jones building in Southend High Street

-

Dixons in 1969

-

Havens (left) in 2015

Southend was not always full of chain stores, with many historical independent stores closing during the 70s, 80s and 90s.

- Keddies was a nationally recognised department store opened in 1892. The store, located in the High Street, went into administration in 1996.

- J F Dixons opened as a drapers in 1913 on the corner of London Road and what is now the High Street. Expansion before World War II saw it become a department store. The business closed in 1973.

- Brightwells was a department store that opened in 19th century. The store closed in the 1970s.

- Havens was a department store that opened in 1901, in Hamlet Court Road, Westcliff-on-Sea.[324][333] In May 2017, Havens announced that they would be closing their store to concentrate as an online retailer.[334]

- Garons opened as a grocers at 64 High Street in 1885.[335] The grocers in 1910 opened a cinema and cafe, which had a ballroom added in 1920.[336] The company further expanded the grocery side of the business, opening a large bakery in Sutton Road, and by 1946 branches were operating as grocers, butchers and greengrocers across the town.[337][338] The company also grew their catering facilities with the construction of Center House at 66-68 High Street.[339] In 1962, the 45 grocery stores across Essex and the bakery was sold to Moores Stores.[340] The cinema was closed a year later, with the premises sold to make way for a development by Hammerson and the remaining business, including the new Garons 1 Banqueting suite at Victoria Circus was sold to G and W Walker in 1972.[173][341][342] Garon Park was built on land donated by the family.

- R. A. Jones was a jewellers that was opened by Robert Arthur Jones in 1890. Jones would go on and become a benefactor for the town. The store closed in 1979.[343]

- Owen Wallis purchased an existing ironmongers store located in the High Street in around 1882.[344] The store expanded into selling toys, before closing in the 1980s.[345][346][347]

- Bermans was a sports and toy retailer who operated from Southchurch Road. The store closed in the 1980s.[348][346]

- J Patience was a photographic retailers located in Queens Road.[349][350]

- Schofield and Martin was a grocery firm with stores across Southend, that was purchased by Waitrose in 1944 with the name being used until the 1960s. The Alexandra Street branch was the first Waitrose store in 1951 to be made self-service.[351][352]

- Ravens was the longest surviving independent retail business in Southend. The outfitters was started in 1897 by Percy Raven from a small store in the High Street. The business moved to a larger store in the High Street designed by architect Mr Grover,[353] before moving to a newer store on London Road in the 1930s. The store relocated to Clifftown Road in 1952, and operated from the site until its closure in 2017.[354][355][356][357]

- LL Wellfare was a furniture and electrical store based in Sutton Road, which was started in 1946 by Linton Wellfare. The business closed in 2010 after the retirement of Linton's son Richard.[358][359]

Gross value added

[edit]As of 2014, the Office for National Statistics reported that Southend's gross value added to the economy was as follows:[360]

| Period | Value £m |

|---|---|

| 1997 | 58 |

| 1998 | 62 |

| 1999 | 73 |

| 2000 | 100 |

| 2001 | 89 |

| 2002 | 100 |

| 2003 | 100 |

| 2004 | 103 |

| 2005 | 95 |

| 2006 | 94 |

| 2007 | 94 |

| 2008 | 83 |

| 2009 | 68 |

| 2010 | 48 |

| 2011 | 72 |

| 2012 | 86 |

Transport

[edit]Airport

[edit]

London Southend Airport was developed from the military airfield at Rochford; it was opened as a civil airport in 1935. The airport was the UK's third-busiest airport during the 1960s, behind Heathrow and Manchester, before passenger numbers dropped off in the 1970s.[361] In 2008, Stobart Group bought the lease for £21 million, becoming part of the Stobart Air division of the Stobart Group,[362] who completed a rebuilding of the airport during 2010.[363] It now offers scheduled flights to destinations across Europe, corporate and recreational flights, aircraft maintenance and training for pilots and engineers. It is served by Southend Airport railway station, on the Shenfield–Southend line, part of the Great Eastern Main Line.

Buses

[edit]

Local bus services are provided by two main companies. Arriva Southend was formerly the council-owned Southend-on-Sea Corporation Transport and First Essex Buses was formerly Eastern National/Thamesway. Smaller providers include Stephensons of Essex. Southend-on-Sea Corporation Transport had been started by the council as a Tram service in 1901, before moving into Trolleybuses and Motorbuses, before being sold off to British Bus in 1993.[364][365][366]

Southend has a bus station, known as the Southend Travel Centre, on Chichester Road, which was developed from a temporary facility added in the 1970s in 2006.[367] The previous bus station was located on London Road and was run by Eastern National, but it was demolished in the 1980s to make way for a Sainsbury's supermarket.[368] Arriva Southend is the only bus company based in Southend, with their depot located in Short Street; it was previously sited on the corner of London Road and Queensway and also a small facility in Tickfield Road.[369] First Essex's buses in the Southend area are based out of the depot in Hadleigh but, prior to the 1980s, Eastern National had depots on London Road (at the bus station) and Fairfax Drive.[370]

First Essex run the Essex Airlink bus service from the Southend Travel Centre to London Stansted.

Railway

[edit]-

A c2c train at Southend Central station

-

Southend Victoria station

-

Southend Cliff Railway

Southend is served by two lines on the National Rail network:

- Running from Southend Victoria north out of the city is the Shenfield–Southend line, a branch of the Great Eastern Main Line, operated by Abellio Greater Anglia. Services operate to London Liverpool Street, via Shenfield.

- Running from Shoeburyness, in the east of the borough, is the London, Tilbury and Southend line operated by c2c. It runs west through Thorpe Bay, Southend East, Southend Central to London Fenchurch Street, either via Benfleet and Basildon or Tilbury Town and Barking. Additionally, one service from Southend Central each weekday evening terminates at Liverpool Street.

From 1910 to 1939, the London Underground's District line's eastbound service ran as far as Southend and Shoeburyness.[371]

Besides its main line railway connections, Southend is also the home of two smaller railways. The Southend Pier Railway provides transport along the length of Southend Pier, whilst the nearby Southend Cliff Railway provides a connection from the promenade to the cliff top above.[372]

Roads

[edit]

Two A-roads connect Southend with London and the rest of the country: the A127 (Southend Arterial Road), via Basildon and Romford, and the A13, via Thurrock and London Docklands. Both are major routes; however, within the borough, the A13 is now a single carriageway local single-carriageway route, whereas the A127 is an entirely dual-carriageway. Both connect to the M25 and eventually London.

Climate

[edit]

Southend-on-Sea is one of the driest places in the UK. It has a marine climate with summer highs of around 22 °C (72 °F) and winters highs being around 7.8 °C (46.0 °F).[373] Summer temperatures are generally slightly cooler than those in London. Frosts are occasional. During the 1991–2020 period there was an average of 29.6 days of air frost. Rainfall averaged 527 millimetres (20.7 in). Weather station data is available from Shoeburyness, a suburb of the city.[373]

| Climate data for Shoeburyness, in eastern part of Southend Urban Area, 2m asl, 1991–2020 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.8 (46.0) |

8.3 (46.9) |

10.6 (51.1) |

13.5 (56.3) |

16.6 (61.9) |

19.8 (67.6) |

22.3 (72.1) |

22.4 (72.3) |

19.4 (66.9) |

15.3 (59.5) |

11.1 (52.0) |

8.4 (47.1) |

14.6 (58.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.7 (36.9) |

2.4 (36.3) |

3.7 (38.7) |

5.4 (41.7) |

8.3 (46.9) |

11.2 (52.2) |

13.6 (56.5) |

13.8 (56.8) |

11.5 (52.7) |

8.9 (48.0) |

5.5 (41.9) |

3.2 (37.8) |

7.5 (45.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 43.0 (1.69) |

36.1 (1.42) |

32.7 (1.29) |

36.1 (1.42) |

41.6 (1.64) |

44.1 (1.74) |

41.1 (1.62) |

48.6 (1.91) |

43.0 (1.69) |

57.8 (2.28) |

54.0 (2.13) |

48.8 (1.92) |

526.9 (20.75) |

| Average rainy days | 9.5 | 8.3 | 7.8 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 7.8 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 7.5 | 10.2 | 10.6 | 10.7 | 101.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 70.5 | 88.9 | 136.8 | 200.4 | 241.2 | 243.3 | 257.0 | 212.2 | 162.4 | 130.0 | 84.7 | 56.9 | 1,884.3 |

| Source: Met Office[374] | |||||||||||||

Education

[edit]-

University of Essex accommodation in Southend

-

Cecil Jones Academy

-

South Essex College Southend Campus

-

Southend Adult Community College

Secondary schools

[edit]Southend has a mixture of secondary school offerings. The mainstream secondary schools are mixed-sex comprehensives, including Belfairs Academy; Cecil Jones Academy; Chase High School; Southchurch High School; Shoeburyness High School and The Eastwood Academy.

In 2004, Southend retained the grammar school system and has four such schools: Southend High School for Boys; Southend High School for Girls; Westcliff High School for Boys and Westcliff High School for Girls.

Additionally, there are two single-sex schools assisted by the Roman Catholic Church: St Bernard's High School (girls) and St Thomas More High School (boys).

Higher and further education

[edit]The main higher education provider in Southend is the University of Essex which has a campus in Elmer Approach, that opened in 2007 and is on the site of the former Odeon cinema.[375][376] The University has operated from the city since 2003 when they opened a new satellite campus at Princess Caroline House in the High Street.[377] It also operates the East 15 Acting School Southend campus at the Clifftown Theatre.[378]

In addition to a number of secondary schools that offer further education, the largest provider is South Essex College in a purpose-built building in the centre of town. Formerly known as South East Essex College, (and previously Southend Municipal College) the college changed name in January 2010 following a merger with Thurrock and Basildon College.[379]

Additionally there is PROCAT, (an arm of South Essex College) that is based at Progress Road, while learners can travel to USP College (formerly SEEVIC College) in Thundersley. The East 15 Acting School, a drama school has its second campus in Southend, while the Southend Adult Community College is in Ambleside Drive. Southend United Futsal & Football Education Scholarship, located at Southend United's stadium Roots Hall, provides education for sports scholarships.

Formation of education in the city

[edit]Primary education

[edit]The first school in the city opened in Prittlewell in 1727, after the Reverend Case campaigned for one to be setup. Land was provided by the Lord of the Manor Daniel Scratton in North Street for establishment of a school, and by 1739, Scratton had donated a further 21 acres of land. The school was by subscription of 1d a week, with 16 free places provided, and the remainder of the funding provided by a partial subscription of the parish and collections at St Mary's.[380] The Parliamentary commission into charities of 1819-37 described the school as "The premises consists of a house of lath and plaster, situate in the village near the bridge; it comprises a schoolroom of about 30ft. in length and 20ft. in breadth, and several other rooms which are appropriated to the use of the schoolmaster".[380]

After Southend became a separate ecclesiastical district in 1842, the church of St. John's the Baptist founded the subscription National School in 1855 in Lower Southend.[380] By 1876, the Board of Education called for a local board of education be setup and extra places be created. At the time of their report Southend had the following schools providing education for under 12s:

- Prittlewell Church of England - 175 pupils

- British School - 233 pupils

- Miss Felton's Infant School - 7 pupils

- Grovesnor School - 54 pupils

It was reported that the National School had closed and that Southend required a further 220 places. Many parishioners were against a local school board being setup, but Daniel Scratton was for the development, and by 1877 the Prittlewell School Board was formed.[380]

By 1879, a new school was created called the London Road Schools which had places for over 500 pupils, and Prittlewell Church of England school had moved to East Street.[380] However, by 1892, with further expansion of Southend, the Brewery Road School (now called Porters Grange) opened, followed by Leigh Road (which would become Hamlet Court County School) in 1897, Southchurch Hall in 1904, Bournemouth Park in 1907 and Chalkwell Park in 1909.[380][381] The local board was dissolved by the Education Act of 1902 and replaced by the education committee of the council.[380]

Secondary and further education

[edit]The Science and Art Department formation in 1853 had seen the government push for education in art, science, technology, and design in Britain and Ireland.[382] The movement did not arrive in Southend until 1882 when two evening classes were set up at the London Road Schools for Art and Physiology.[380] By 1883 the classes were moved to Clarence Street in a building shared with the council.[380]

The Technical Instruction Act of 1889 and 1891 allowed councils to provide evening classes for technical subjects. The local board set up the Technical Instruction Committee, and soon classes were started at the council offices in Clarence Road. They were extremely popular, and the following year the newly created Southend Corporation purchased further land in Clarence Road to build a Technical Institute.[383] In 1895 the foundation stone was laid, but prior to it opening it was decided to also open a day technical school for about 20 pupils, influenced by the Bryce commission of 1894. The first headmaster was J Hitchcock from Woolwich and was supported by one assistant teacher.[384] A one-day a week art school was opened, which by 1899 was a fully organised art college.[385]

The Day Technical School soon outgrew the Clarence Road site, and in 1902 a new building opened at Victoria Circus to host them, the Evening Technical Institute and the School of Art.[44][45][46] In 1907, Essex County Council formed a new Higher Education committee, who decided that education should be split into separate boys and girls schools. In 1912, a foundation stone was laid in Boston Avenue for a new girls school, and a year later the girls left the Day Technical School to the new Southend High School for Girls.[51] The Day Technical School was renamed as Southend High School for Boys.[52] In 1914, Southend became a County Borough, taking charge of all education in the town, including the High School, School of Art and the Evening class institute all located still in the same building.[386] After the war the number of pupils increased, so in 1919 the School of Art moved out of the top floor to make room for the High School, into temporary wooden buildings at the rear of the building.[387] In 1920, The Commercial School was a co-educational school opened for the town’s rapidly expanding population in Bellsfield, a former large house located on Victoria Avenue.[388] Two years later, the school's name changed from The Commercial School to Westcliff High School, and by 1926, boys attending the school had moved to the school's present site on Kenilworth Gardens, becoming Westcliff High School for Boys. The accompanying girls' school, Westcliff High School for Girls, remained on the Victoria Avenue site until 1930, following their relocation to the same site as Westcliff High School for Boys.[388] The plans for the purchased land at the corner of Victoria Avenue and Carnarvon Road was changed in 1934 when it was decided to use this as the site of a new town hall.[389]