Abortion in Minnesota

Abortion in Minnesota is legal at all stages of pregnancy[1][2] and is restricted only to standards of good medical practice.[3][4] The Minnesota Supreme Court ruled the Minnesota Constitution conferred a right to an abortion in 1995 and the DFL-led Minnesota Legislature passed and Minnesota Governor Tim Walz signed into law a bill in 2023 to recognize a right to reproductive freedom and preventing local units of government from limiting that right. The Center for Reproductive Rights labels Minnesota as one of the most abortion-protective states in the country.[5]

About 10,000 abortions occur each year in the state.

In a 2014 Pew Research Center survey, 52% of Minnesota adults said that abortion should be legal in all or most cases, while 45% said that abortion should be illegal in all or most cases.[6] The 2023 American Values Atlas reported that, in their most recent survey, 67% of Minnesotans said that abortion should be legal in all or most cases.[7]

Background

[edit]Abortion was a criminal offense for women by 1950. By 2007, the state had informed consent laws on the book. The state legislature passed abortion restrictions in 2011, 2012[8] and 2018[9] that were ultimately all vetoed by DFL governor Mark Dayton.[10][11]

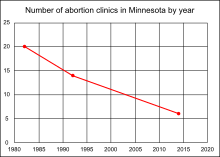

The number of abortion clinics have been declining in recent years, going from twenty in 1982 to fourteen in 1992 to six in 2014. There were 10,123 legal abortions performed in 2014, and 9,861 in 2015.[12] Abortion was criminally prosecuted between 1911 and 1930, resulting in 30 convictions against women in that period.

By 2019, Minnesota was one of only two states in the nation (along with Alabama) that did not have a law that terminated parental rights of men who produced a child via rape or incest.[13][14]

Today, the state has an active abortion rights community, including the organization UnRestrict MN [15] and Pro-Choice Minnesota,[16][17] involved in activities such as facilitating travel for women seeking abortions and advocating in support of abortion rights. There is also an active anti-abortion rights community, which includes organizations like Minnesota Family Council and Minnesota Citizens Concerned for Life.

History

[edit]Legislative history

[edit]In the 1950s, the state legislature passed a law stating that a woman who had an abortion or actively sought one (regardless of whether she went through with it) was guilty of a criminal offense.[18] Parental consent laws passed by Massachusetts and Minnesota in the 1980s created over 12,000 petitions to bypass consent. Of these, 21 were denied and half of these denials were overturned on appeal.[19][20]

The state was one of 23 states in 2007 to have a detailed abortion-specific informed consent requirement.[21] Arkansas, Minnesota and Oklahoma all require that women seeking abortions after 20-weeks be verbally informed that the fetus may feel pain during the abortion procedure despite a Journal of the American Medical Association conclusion that pain sensors do not develop in the fetus until between weeks 23 and 30.[22] The state legislature was one of four states nationwide that tried, and failed, to pass an early abortion ban in 2012 (often called a "fetal heartbeat bill" by proponents).[23] It was also introduced in 2019 by Representative Tim Miller.[24]

In 2018, the state was one of eleven where the legislature introduced a bill that would have banned abortion in almost all cases. It did not pass.[23] The state legislature was one of ten states nationwide that tried to unsuccessfully pass a "heartbeat bill" in 2018. Only Iowa successfully passed such a bill, but it was struck down by the courts.[23] As of May 14, 2019, the state prohibited abortions after the fetus was viable, generally some point between weeks 24 and 28 in gestation. This period was defined by the US Supreme Court in their landmark 1973 case Roe v. Wade.[23]

Protect Reproductive Options Act

[edit]In January 2023, the Minnesota Legislature passed the Protecting Reproductive Options Act to "explicitly protect and codify abortion rights" within Minnesota law. Tim Walz, the Governor of Minnesota, signed the bill into law on January 31, 2023.[25][26]

Judicial history

[edit]In a 1894 case on abortion, the Minnesota Supreme Court said, "As a first impression, it may seem to be an unsound rule that one who solicits the commission of an offense, and willingly submits to its being committed upon her own person, should not be deemed an accomplice, while those whom she has thus solicited should be deemed principal criminals in the transaction. But in cases of this kind the public welfare demands the application of this rule, and its exceptions from the general rule seems to be justified by the wisdom of experience. The wife, then, in this case, was not, within the rules of the law, an accomplice. She was the victim of the cruel act which resulted in her death. Misguided by her own desires, and mistaken in her belief, she, by the advice of the defendant, submitted to his treatment, willing, it may be; but the desire of one, and the criminal act of the other, resulted in the death of one, and the imprisonment of the other."[18]

Roe v. Wade

[edit]The US Supreme Court's decision in 1973's Roe v. Wade ruling meant the state could no longer regulate abortion in the first trimester.[18] However, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, No. 19-1392, 597 U.S. ___ (2022) later in 2022.[27][28]

Hodgson v. Minnesota

[edit]The 1990 US Supreme Court case Hodgson v. Minnesota said that parental consent can cause danger for minors seeking abortions if physical, emotional or sexual abuse is already present.[19][29] The case concerned a Minnesota law that required notifying both parents of a minor before she could undergo an abortion; it also contained a judicial bypass provision designed to take effect only if a court found it necessary.[30] Dr. Jane Hodgson, a Minneapolis gynecologist, challenged the law. The Eighth Circuit had ruled that the law would have been unconstitutional without a judicial bypass option.[30] While Justice Stevens delivered a majority opinion for one of the holdings, there were five votes for each of two holdings, with Justice O'Connor proving as the decisive vote for each.[30] Justices Stevens, Brennan, Marshall, Blackmun and O'Connor formed a majority holding that the two-parent notice requirement by itself was unconstitutional.[30] Justice O'Connor believed that the two-parent requirement entailed risk to a pregnant teenager; she also argued that the rule failed to meet even the lowest standard of judicial review, a rationality standard.[30] She joined the Court's more conservative Justices (Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justices White, Scalia and Kennedy), to form a majority for the law being valid with the judicial bypass; Justice Kennedy had pointed out the usefulness of the bypass procedure, as judges granted all but a handful of requests to authorize abortions without parental notice.[30]

Doe v. Gomez

[edit]In 1995, the Minnesota Supreme Court ruled in Doe v. Gomez that the Minnesota Constitution conferred a right to an abortion and public funding for an abortion.[31] A 2022 ruling by a state district court in Doe v. Minnesota decided that certain regulations on abortion were also unconstitutional.[32]

Clinic history

[edit]

Between 1982 and 1992, the number of abortion clinics in the state decreased by six, going from twenty in 1982 to fourteen in 1992.[33] In 2014, there were six abortion clinics in the state.[34] In 2014, 95% of the counties in the state did not have an abortion clinic. That year, 59% of women in the state aged 15–44 lived in a county without an abortion clinic.[35]

Statistics

[edit]In the period between 1972 and 1974, there were no recorded illegal abortion-related death in the state.[36] In 1990, 529,000 women in the state faced the risk of an unintended pregnancy.[33] In 2013, among white women aged 15–19, there were 510 abortions, 260 abortions for black women aged 15–19, 80 abortions for Hispanic women aged 15–19, and 140 abortions for women of all other races.[37]

In 2014, 52% of adults said in a poll conducted by the Pew Research Center that abortion should be legal in all or most cases. 45% said they opposed abortion in all or most cases.[38] The New York Times estimated that in 2022, 54% of Minnesotan's thought abortion should be "mostly legal", while 40% thought it should be "mostly illegal".[39]

| Census division and state | Number | Rate | % change 1992–1996 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | 1995 | 1996 | 1992 | 1995 | 1996 | ||

| West North Central | 57,340 | 48,530 | 48,660 | 14.3 | 11.9 | 11.9 | –16 |

| Iowa | 6,970 | 6,040 | 5,780 | 11.4 | 9.8 | 9.4 | –17 |

| Kansas | 12,570 | 10,310 | 10,630 | 22.4 | 18.3 | 18.9 | –16 |

| Minnesota | 16,180 | 14,910 | 14,660 | 15.6 | 14.2 | 13.9 | –11 |

| Missouri | 13,510 | 10,540 | 10,810 | 11.6 | 8.9 | 9.1 | –21 |

| Nebraska | 5,580 | 4,360 | 4,460 | 15.7 | 12.1 | 12.3 | –22 |

| North Dakota | 1,490 | 1,330 | 1,290 | 10.7 | 9.6 | 9.4 | –13 |

| South Dakota | 1,040 | 1,040 | 1,030 | 6.8 | 6.6 | 6.5 | –4 |

| Location | Residence | Occurrence | % obtained by

out-of-state residents |

Year | Ref | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Rate^ | Ratio^^ | No. | Rate^ | Ratio^^ | ||||

| Minnesota | 15.6 | 1992 | [40] | ||||||

| Minnesota | 14,910 | 14.2 | 1995 | [40] | |||||

| Minnesota | 14,660 | 13.9 | 1996 | [40] | |||||

| Minnesota | 9,533 | 9.1 | 136 | 10,123 | 9.6 | 145 | 9.3 | 2014 | [41] |

| Minnesota | 9,234 | 8.8 | 132 | 9,861 | 9.4 | 141 | 9.8 | 2015 | [42] |

| Minnesota | 9,425 | 8.9 | 135 | 10,017 | 9.5 | 144 | 9.0 | 2016 | [43] |

| ^number of abortions per 1,000 women aged 15–44; ^^number of abortions per 1.000 live births | |||||||||

Criminal prosecutions of abortion

[edit]Between 1911 and 1930, there were 100 indictments and 30 convictions for women having abortions.[18] Dr. Jane Hodgson was convicted in 1970 of performing an illegal abortion on a 23-year-old woman in Minnesota. Hodgson was an abortion rights activist.[44]

Abortion financing

[edit]Minnesota is one of seventeen states that uses state funds to cover all or most medically necessary abortions sought by low-income women under Medicaid. Minnesota is one of thirteen other states that are required by State court orders to do so.[45] In 2010, the state had 3,941 publicly funded abortions, of which sixteen were federally funded and 3,925 were state funded.[46]

Abortion rights views and activities

[edit]Protests

[edit]Following the overturn of Roe v. Wade on June 24, 2022, abortion rights protests were held in Minneapolis and Saint Paul.[47] An abortion rights protest was also held in St. Cloud at the Stearns County Courthouse.[48]

Anti-abortion views and activities

[edit]Organizations

[edit]Minnesota Family Council (MFC) is a Christian organization that, among other issues, opposes abortion and abortion-related education in public schools, stating that: "human life is sacred from conception to natural death and must be protected by government".[49]

Violence

[edit]In 1977, there was an arson attack on a Minnesota abortion clinic.[50] An act of violence took place at an abortion clinic in Crow Wing County, Minnesota.[50] On January 22, 2009, Matthew L. Derosia, 32, who was reported to have had a history of mental illness, rammed an SUV into the front entrance of a Planned Parenthood clinic in Saint Paul, Minnesota, causing between $2,500 and $5,000 in damage.[51][52] Derosia, who told police that Jesus told him to "stop the murderers", was ruled competent to stand trial. He pleaded guilty in March 2009 to one count of criminal damage to property.[52]

References

[edit]- ^ "Where Can I Get an Abortion? | U.S. Abortion Clinic Locator". www.abortionfinder.org. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ^ Institute, Guttmacher. "Interactive Map: US Abortion Policies and Access After Roe". states.guttmacher.org. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ^ "MMA Policies 2023" (PDF). Minnesota Medical Association.

- ^ "147.091 Grounds for Disciplinary Action". 2023 Minnesota Statutes.

- ^ "Minnesota". Center for Reproductive Rights. Retrieved August 28, 2024.

- ^ "Views about abortion among adults in Minnesota". Pew Research. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ "Abortion Views in All 50 States: Findings from PRRI's 2023 American Values Atlas | PRRI". PRRI | At the intersection of religion, values, and public life. May 2, 2024. Retrieved October 30, 2024.

- ^ "2012 Saw Second-Highest Number of Abortion Restrictions Ever". Guttmacher Institute. January 2, 2013. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Kayser, Zach (May 10, 2018). "Controversial abortion bill heads for governor's desk - Session Daily". Minnesota House of Representatives. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Bailey, David (May 25, 2011). "Minnesota governor vetoes 20-week abortion law". U.S. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Magan, Christopher (May 16, 2018). "Mark Dayton vetoes bill requiring a chance to see an ultrasound before an abortion". Twin Cities. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Induced Abortions in Minnesota January - December 2015: Report to the Legislature (PDF) (Report). July 2016.

- ^ Wax-Thibodeaux, Emily (June 9, 2019). "In Alabama — where lawmakers banned abortion for rape victims — rapists' parental rights are protected". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 10, 2019.

- ^ Michaels, Samantha (June 6, 2019). "Alabama banned abortions. Then its lawmakers remembered rapists can get parental rights". Mother Jones. Retrieved June 8, 2019.

- ^ "Unrestrict Minnesota". Gender Justice. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ "Pro-Choice Minnesota". National Institute for Reproductive Health. February 15, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ^ "Pro-Choice Minnesota". Pro-Choice Minnesota. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Buell, Samuel (January 1, 1991). "Criminal Abortion Revisited". New York University Law Review. 66 (6): 1774–1831. PMID 11652642.

- ^ a b Adolescence, Committee On (February 1, 2017). "The Adolescent's Right to Confidential Care When Considering Abortion". Pediatrics. 139 (2): e20163861. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-3861. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 28115537.

- ^ Crosby, Margaret C.; English, Abigail (March 1991). "Mandatory parental involvement/judicial bypass laws: Do they promote adolescents' health?". Journal of Adolescent Health. 12 (2): 143–147. doi:10.1016/0197-0070(91)90457-w. ISSN 1054-139X. PMID 2015239.

- ^ "State Policy On Informed Consent for Abortion" (PDF). Guttmacher Policy Review. Fall 2007. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- ^ "State Abortion Counseling Policies and the Fundamental Principles of Informed Consent". Guttmacher Institute. November 12, 2007. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Lai, K. K. Rebecca (May 15, 2019). "Abortion Bans: 8 States Have Passed Bills to Limit the Procedure This Year". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ "Minnesota Legislature - HF271 - 91st Legislature (2019–2020)". revisor.mn.gov. Office of the Revisor of Statutes. Retrieved February 13, 2019.

Description: Abortion prohibited when a fetal heartbeat is detected with certain exceptions, and penalties provided.

- ^ Derosier, Alex (January 27, 2023). "Minnesota Senate sends abortion rights protections to governor's desk". Duluth News Tribune. Retrieved January 29, 2023.

- ^ "HF 1". Minnesota House of Representatives. January 31, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ de Vogue, Ariane (June 24, 2022). "Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade". CNN. Archived from the original on June 24, 2022. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- ^ Howe, Amy (June 24, 2022). "Supreme Court overturns constitutional right to abortion". SCOTUSblog. Archived from the original on June 24, 2022. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- ^ "Timeline of Important Reproductive Freedom Cases Decided by the Supreme Court". American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Greenhouse, Linda (2005), Becoming Justice Blackmun, Times Books, pp. 196–197

- ^ Doe v. Gomez

- ^ Doe v. Minnesota

- ^ a b Arndorfer, Elizabeth; Michael, Jodi; Moskowitz, Laura; Grant, Juli A.; Siebel, Liza (December 1998). A State-By-State Review of Abortion and Reproductive Rights. DIANE Publishing. ISBN 9780788174810.

- ^ Rebecca Harrington; Skye Gould. "The number of abortion clinics in the US has plunged in the last decade — here's how many are in each state". Business Insider. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ Panetta, Grace; lee, Samantha (August 4, 2018). "This is what could happen if Roe v. Wade fell". Business Insider (in Spanish). Archived from the original on May 24, 2019. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ Cates, Willard; Rochat, Roger (March 1976). "Illegal Abortions in the United States: 1972–1974". Family Planning Perspectives. 8 (2): 86–92. doi:10.2307/2133995. JSTOR 2133995. PMID 1269687.

- ^ "No. of abortions among women aged 15–19, by state of residence, 2013 by racial group". Guttmacher Data Center. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ "Views about abortion by state - Religion in America: U.S. Religious Data, Demographics and Statistics". Pew Research Center. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ "Do Americans Support Abortion Rights? Depends on the State". The New York Times. May 4, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Henshaw, Stanley K. (June 15, 2005). "Abortion Incidence and Services in the United States, 1995-1996". Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 30: 263–270. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- ^ Jatlaoui, Tara C. (2017). "Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2014". MMWR. Surveillance Summaries. 66 (24): 1–48. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6624a1. ISSN 1546-0738. PMC 6289084. PMID 29166366.

- ^ Jatlaoui, Tara C. (2018). "Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2015". MMWR. Surveillance Summaries. 67 (13): 1–45. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6713a1. ISSN 1546-0738. PMC 6289084. PMID 30462632.

- ^ Jatlaoui, Tara C. (2019). "Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2016". MMWR. Surveillance Summaries. 68 (11): 1–41. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6811a1. ISSN 1546-0738. PMC 6289084. PMID 31774741.

- ^ Tribune, Chicago. "Timeline of abortion laws and events". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ Francis, Roberta W. "Frequently Asked Questions". Equal Rights Amendment. Alice Paul Institute. Archived from the original on April 17, 2009. Retrieved September 13, 2009.

- ^ "Guttmacher Data Center". data.guttmacher.org. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ "Abortion advocates, opponents rally in Twin Cities following SCOTUS ruling on Roe v. Wade". CBS News. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ "Over 100 people gather in St. Cloud to protest Roe v. Wade reversal, spark change". SC Times. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ "Our Mission". Minnesota Family Foundation. Archived from the original on August 31, 2012. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

- ^ a b Jacobson, Mireille; Royer, Heather (December 2010). "Aftershocks: The Impact of Clinic Violence on Abortion Services". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 3: 189–223. doi:10.1257/app.3.1.189.

- ^ "Man charged with driving into Planned Parenthood facility". Star Tribune. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- ^ a b Pat Pheifer, Cottage Grove man pleads guilty to driving SUV into clinic, Minneapolis Star-Tribune (March 26, 2009).