Caryophyllene

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

(1R,4E,9S)-4,11,11-Trimethyl-8-methylidenebicyclo[7.2.0]undec-4-ene | |

| Other names

β-Caryophyllene

trans-(1R,9S)-8-Methylene-4,11,11-trimethylbicyclo[7.2.0]undec-4-ene | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.588 |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C15H24 | |

| Molar mass | 204.357 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 0.9052 g/cm3 (17 °C)[1] |

| Boiling point | 262–264 °C (504–507 °F; 535–537 K)[2] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

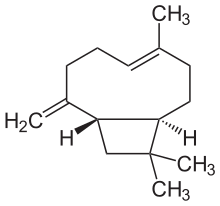

Caryophyllene (/ˌkærioʊˈfɪliːn/), more formally (−)-β-caryophyllene (BCP), is a natural bicyclic sesquiterpene that occurs widely in nature. Caryophyllene is notable for having a cyclobutane ring, as well as a trans-double bond in a 9-membered ring, both rarities in nature. [3]

Production

[edit]Caryophyllene can be produced synthetically,[4] but it is invariably obtained from natural sources because it is widespread. It is a constituent of many essential oils, especially clove oil, the oil from the stems and flowers of Syzygium aromaticum (cloves), the essential oil of Cannabis sativa, copaiba, rosemary, and hops.[3] It is usually found as a mixture with isocaryophyllene (the cis double bond isomer) and α-humulene (obsolete name: α-caryophyllene), a ring-opened isomer.

Caryophyllene is one of the chemical compounds that contributes to the aroma of black pepper.[5]

Basic research

[edit]β-Caryophyllene is under basic research for its potential action as an agonist of the cannabinoid receptor type 2 (CB2 receptor).[6] In other basic studies, β-caryophyllene has a binding affinity of Ki = 155 nM at the CB2 receptors.[7]

β-Caryophyllene has the highest cannabinoid activity compared to the ring opened isomer α-caryophyllene humulene which may modulate CB2 activity.[8] To compare binding, cannabinol binds to the CB2 receptors as a partial agonist with an affinity of Ki = 126.4 nM,[9] while delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol binds to the CB2 receptors as a partial agonist with an affinity of Ki = 36 nM.[10]

Safety

[edit]Caryophyllene has been given generally recognized as safe (GRAS) designation by the FDA and is approved by the FDA for use as a food additive, typically for flavoring.[11][12] Rats given up to 700 mg/kg daily for 90 days did not produce any significant toxic effects.[13] Caryophyllene has an LD50 of 5,000 mg/kg in mice.[14][15]

Metabolism and derivatives

[edit]14-Hydroxycaryophyllene oxide (C15H24O2) was isolated from the urine of rabbits treated with (−)-caryophyllene (C15H24). The X-ray crystal structure of 14-hydroxycaryophyllene (as its acetate derivative) has been reported.[16]

The metabolism of caryophyllene progresses through (−)-caryophyllene oxide (C15H24O) since the latter compound also afforded 14-hydroxycaryophyllene (C15H24O) as a metabolite.[17]

- Caryophyllene (C15H24) → caryophyllene oxide (C15H24O) → 14-hydroxycaryophyllene (C15H24O) → 14-hydroxycaryophyllene oxide (C15H24O2).

Caryophyllene oxide,[18] in which the alkene group of caryophyllene has become an epoxide, is the component responsible for cannabis identification by drug-sniffing dogs[19][20] and is also an approved food additive, often as flavoring.[12] Caryophyllene oxide may have negligible cannabinoid activity.[21]

Natural sources

[edit]The approximate quantity of caryophyllene in the essential oil of each source is given in square brackets ([ ]):

- Cannabis (Cannabis sativa) [3.8–37.5% of cannabis flower essential oil][22]

- Black caraway (Carum nigrum) [7.8%][23]

- Cloves (Syzygium aromaticum) [1.7–19.5% of clove bud essential oil][24]

- Hops (Humulus lupulus)[25] [5.1–14.5%][26]

- Basil (Ocimum spp.)[27] [5.3–10.5% O. gratissimum; 4.0–19.8% O. micranthum][28]

- Oregano (Origanum vulgare)[29] [4.9–15.7%][30][31]

- Black pepper (Piper nigrum) [7.29%][5]

- Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) [4.62–7.55% of lavender oil][32][33]

- Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis)[34] [0.1–8.3%][citation needed]

- True cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum) [6.9–11.1%][35]

- Malabathrum (Cinnamomum tamala) [25.3%][36]

- Ylang-ylang (Cananga odorata) [3.1–10.7%]

- Copaiba oil (Copaifera)[37][38]

Biosynthesis

[edit]Caryophyllene is a common sesquiterpene among plant species. It is biosynthesized from the common terpene precursors dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) and isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP). First, single units of DMAPP and IPP are reacted via an SN1-type reaction with the loss of pyrophosphate, catalyzed by the enzyme GPPS2, to form geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP). This further reacts with a second unit of IPP, also via an SN1-type reaction catalyzed by the enzyme IspA, to form farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP). Finally, FPP undergoes QHS1 enzyme-catalyzed intramolecular cyclization to form caryophyllene.[39]

Compendial status

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Ghelardini, C.; Galeotti, N.; Di Cesare Mannelli, L.; Mazzanti, G.; Bartolini, A. (2001). "Local anaesthetic activity of beta-caryophyllene". Farmaco. 56 (5–7): 387–389. doi:10.1016/S0014-827X(01)01092-8. hdl:2158/397975. PMID 11482764.

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ SciFinder Record, CAS Registry Number 87-44-5

- ^ Baker, R. R. (2004). "The pyrolysis of tobacco ingredients". Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis. 71 (1): 223–311. doi:10.1016/s0165-2370(03)00090-1.

- ^ a b Sell, Charles S. (2006). "Terpenoids". Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. doi:10.1002/0471238961.2005181602120504.a01.pub2. ISBN 0471238961.

- ^ Corey, E. J.; Mitra, R. B.; Uda, H. (1964). "Total Synthesis of d,l-Caryophyllene and d,l-Isocaryophyllene". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 86 (3): 485–492. doi:10.1021/ja01057a040.

- ^ a b Jirovetz, L.; Buchbauer, G.; Ngassoum, M. B.; Geissler, M. (November 2002). "Aroma compound analysis of Piper nigrum and Piper guineense essential oils from Cameroon using solid-phase microextraction–gas chromatography, solid-phase microextraction–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and olfactometry". Journal of Chromatography A. 976 (1–2): 265–275. doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(02)00376-X. PMID 12462618.

- ^ Ceccarelli, Ilaria; Fiorenzani, Paolo; Pessina, Federica; Pinassi, Jessica; Aglianò, Margherita; Miragliotta, Vincenzo; Aloisi, Anna Maria (18 August 2020). "The CB2 Agonist β-Caryophyllene in Male and Female Rats Exposed to a Model of Persistent Inflammatory Pain". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 14: 850. doi:10.3389/fnins.2020.00850. PMC 7461959. PMID 33013287.

- ^ Alberti, Thaís Barbosa; Barbosa, Wagner Luiz Ramos; Vieira, José Luiz Fernandes; Raposo, Nádia Rezende Barbosa; Dutra, Rafael Cypriano (1 April 2017). "(−)-β-Caryophyllene, a CB2 Receptor-Selective Phytocannabinoid, Suppresses Motor Paralysis and Neuroinflammation in a Murine Model of Multiple Sclerosis". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 18 (4): 691. doi:10.3390/ijms18040691. PMC 5412277. PMID 28368293.

- ^ Hashiesh, Hebaallah Mamdouh; Sharma, Charu; Goyal, Sameer N.; Sadek, Bassem; Jha, Niraj Kumar; Kaabi, Juma Al; Ojha, Shreesh (1 August 2021). "A focused review on CB2 receptor-selective pharmacological properties and therapeutic potential of β-caryophyllene, a dietary cannabinoid". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 140: 111639. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111639. PMID 34091179. S2CID 235362290.

- ^ Russo, Ethan B.; Marcu, Jahan (2017). "Cannabis Pharmacology: The Usual Suspects and a Few Promising Leads". Cannabinoid Pharmacology. Advances in Pharmacology. Vol. 80. pp. 67–134. doi:10.1016/bs.apha.2017.03.004. ISBN 978-0-12-811232-8. PMID 28826544.

- ^ Bow, Eric W.; Rimoldi, John M. (28 June 2016). "The Structure–Function Relationships of Classical Cannabinoids: CB1/CB2 Modulation". Perspectives in Medicinal Chemistry. 8: 17–39. doi:10.4137/PMC.S32171. PMC 4927043. PMID 27398024.

- ^ "Nomination Background: beta-Caryophyllene (CASRN: 87-44-5)" (PDF).

- ^ a b "CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21".

- ^ Schmitt, D.; Levy, R.; Carroll, B. (2016). "Toxicological Evaluation of β-Caryophyllene Oil". International Journal of Toxicology. 35 (5): 558–567. doi:10.1177/1091581816655303. PMID 27358239. S2CID 206689471.

- ^ "β-Caryophyllene - SDS". Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ "Oil of cinnamon - SDS" (PDF). Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^

- • Asakawa, Y.; Taira, Z.; Takemoto, T.; Ishida, T.; Kido, M.; Ichikawa, Y. (June 1981). "X-Ray Crystal Structure Analysis of 14-Hydroxycaryophyllene Oxide, a New Metabolite of (—)-Caryophyllene, in Rabbits". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 70 (6): 710–711. doi:10.1002/jps.2600700642. PMID 7252830. S2CID 38358882.

- • Adams, T.B.; Gavin, C. Lucas; McGowen, M.M.; Waddell, W.J.; Cohen, S.M.; Feron, V.J.; Marnett, L.J.; Munro, I.C.; Portoghese, P.S.; Rietjens, I.M.C.M.; Smith, R.L. (2011). "The FEMA GRAS assessment of aliphatic and aromatic terpene hydrocarbons used as flavor ingredients". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 49 (10). Elsevier BV: 2471–2494. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2011.06.011. ISSN 0278-6915. PMID 21726592. S2CID 207734236.

- • Ishida, Takashi (2005). "Biotransformation of Terpenoids by Mammals, Microorganisms, and Plant-Cultured Cells". Chemistry & Biodiversity. 2 (5). John Wiley & Sons, Inc (Swiss Chemical Society): 569–590. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200590038. ISSN 1612-1872. PMID 17192005. S2CID 22213646.

- ^ "Caryophyllene oxide – C15H24O". PubChem. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- ^ Yang, Depo; Michel, Laura; Chaumont, Jean-Pierre; Millet-Clerc, Joëlle (1999). "Use of caryophyllene oxide as an antifungal agent in an in vitro experimental model of onychomycosis". Mycopathologia. 148 (2): 79–82. doi:10.1023/a:1007178924408. PMID 11189747. S2CID 24242933.

- ^ Russo, Ethan B (August 2011). "Taming THC: potential cannabis synergy and phytocannabinoid-terpenoid entourage effects: Phytocannabinoid-terpenoid entourage effects". British Journal of Pharmacology. 163 (7): 1344–1364. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01238.x. PMC 3165946. PMID 21749363.

- ^ Stahl, E.; Kunde, R. (1973). "Die Leitsubstanzen der Haschisch-Suchhunde" [The tracing substances of hashish search dogs]. Kriminalistik (in German). 27: 385–389.

- ^ Wiley, Jenny L.; Marusich, Julie A.; Blough, Bruce E.; Namjoshi, Ojas; Brackeen, Marcus; Akinfiresoye, Luli R.; Walker, Teneille D.; Prioleau, Cassandra; Barrus, Daniel G.; Gamage, Thomas F. (June 2024). "Evaluation of cannabimimetic effects of selected minor cannabinoids and Terpenoids in mice". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 132: 110984. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2024.110984. PMID 38417478. S2CID 267941924.

- ^ Mediavilla, V.; Steinemann, S. "Essential oil of Cannabis sativa L. strains". International Hemp Association. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- ^ Singh, G.; Marimuthu, P.; De Heluani, C. S.; Catalan, C. A. (January 2006). "Antioxidant and biocidal activities of Carum nigrum (seed) essential oil, oleoresin, and their selected components". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 54 (1): 174–181. doi:10.1021/jf0518610. hdl:11336/99544. PMID 16390196.

- ^ Alma, M. Hakki; Ertaş, Murat; Nitz, Siegfrie; Kollmannsberger, Hubert (23 May 2007). "Chemical composition and content of essential oil from the bud of cultivated Turkish clove (Syzygium aromaticum L.)". BioResources. 2 (2): 265–269. doi:10.15376/biores.2.2.265-269.

- ^ Wang, Guodong; Tian, Li; Aziz, Naveed; Broun, Pierre; Dai, Xinbin; He, Ji; King, Andrew; Zhao, Patrick X.; Dixon, Richard A. (6 November 2008). "Terpene Biosynthesis in Glandular Trichomes of Hop". Plant Physiology. 148 (3): 1254–1266. doi:10.1104/pp.108.125187. PMC 2577278. PMID 18775972.

- ^ Bernotienë, G.; Nivinskienë, O.; Butkienë, R.; Mockutë, D. (2004). "Chemical composition of essential oils of hops (Humulus lupulus L.) growing wild in Auktaitija" (PDF). Chemija. 2. 4: 31–36. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 7, 2023. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

- ^ Zheljazkov, V. D.; Cantrell, C. L.; Tekwani, B.; Khan, S. I. (January 2008). "Content, composition, and bioactivity of the essential oils of three basil genotypes as a function of harvesting". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 56 (2): 380–5. doi:10.1021/jf0725629. PMID 18095647.

- ^ Vasconcelos Silva, M. G.; Abreu Matos, F. J.; Oliveira Lopes, P. R.; Oliveira Silva, F.; Tavares Holanda, M. (August 2, 2004). Cragg, G. M.; Bolzani, V. S.; Rao, G. S. R. S. (eds.). "Composition of essential oils from three Ocimum species obtained by steam and microwave distillation and supercritical CO2 extraction". Arkivoc. 2004 (6): 66–71. doi:10.3998/ark.5550190.0005.609. hdl:2027/spo.5550190.0005.609.

- ^ Harvala C, Menounos P, Argyriadou N (February 1987). "Essential oil from Origanum dictamnus". Planta Medica. 53 (1): 107–109. doi:10.1055/s-2006-962640. PMID 17268981. S2CID 260278580.

- ^ Calvo Irabién, L. M.; Yam-Puc, J. A.; Dzib, G.; Escalante Erosa, F.; Peña Rodríguez, L. M. (July 2009). "Effect of postharvest drying on the composition of Mexican oregano (Lippia graveolens) essential oil". Journal of Herbs, Spices & Medicinal Plants. 15 (3): 281–287. doi:10.1080/10496470903379001. S2CID 86208062.

- ^ Mockutė, D.; Bernotienė, G.; Judžentienė, A. (May 2001). "The essential oil of Origanum vulgare L. ssp. vulgare growing wild in Vilnius district (Lithuania)". Phytochemistry. 57 (1): 65–69. Bibcode:2001PChem..57...65M. doi:10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00474-x. PMID 11336262.

- ^ Prashar, A.; Locke, I. C.; Evans, C. S. (2004). "Cytotoxicity of lavender oil and its major components to human skin cells". Cell Proliferation. 37 (3): 221–229. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2184.2004.00307.x. PMC 6496511. PMID 15144499.

- ^ Umezu, T.; Nagano, K.; Ito, H.; Kosakai, K.; Sakaniwa, M.; Morita, M. (December 2006). "Anticonflict effects of lavender oil and identification of its active constituents". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 85 (4): 713–721. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2006.10.026. PMID 17173962. S2CID 21779233.

- ^ Ormeño, E.; Baldy, V.; Ballini, C.; Fernández, C. (September 2008). "Production and diversity of volatile terpenes from plants on calcareous and siliceous soils: effect of soil nutrients". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 34 (9): 1219–1229. Bibcode:2008JCEco..34.1219O. doi:10.1007/s10886-008-9515-2. PMID 18670820. S2CID 28717342.

- ^ Kaul, Pran N; Bhattacharya, Arun K; Rajeswara Rao, Bhaskaruni R; Syamasundar, Kodakandla V; Ramesh, Srinivasaiyer (1 January 2003). "Volatile constituents of essential oils isolated from different parts of cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum Blume)". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 83 (1): 53–55. Bibcode:2003JSFA...83...53K. doi:10.1002/jsfa.1277.

- ^ Ahmed, Aftab; Choudhary, M. Iqbal; Farooq, Afgan; Demirci, Betül; Demirci, Fatih; Başer, K. Hüsnü Can (2000). "Essential oil constituents of the spice Cinnamomum tamala (Ham.) Nees & Eberm". Flavour and Fragrance Journal. 15 (6): 388–390. doi:10.1002/1099-1026(200011/12)15:6<388::AID-FFJ928>3.0.CO;2-F.

- ^ Leandro, Lidiam Maia; de Sousa Vargas, Fabiano; Barbosa, Paula Cristina Souza; Neves, Jamilly Kelly Oliveira; da Silva, José Alexsandro; da Veiga-Junior, Valdir Florêncio (30 March 2012). "Chemistry and Biological Activities of Terpenoids from Copaiba (Copaifera spp.) Oleoresins". Molecules. 17 (4): 3866–3889. doi:10.3390/molecules17043866. PMC 6269112. PMID 22466849.

- ^ Sousa, João Paulo B.; Brancalion, Ana P.S.; Souza, Ariana B.; Turatti, Izabel C.C.; Ambrósio, Sérgio R.; Furtado, Niege A.J.C.; Lopes, Norberto P.; Bastos, Jairo K. (March 2011). "Validation of a gas chromatographic method to quantify sesquiterpenes in copaiba oils". Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 54 (4): 653–659. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2010.10.006. PMID 21095089.

- ^ Yang, Jianming; Li, Zhengfeng; Guo, Lizhong; Du, Juan; Bae, Hyeun-Jong (December 2016). "Biosynthesis of β-caryophyllene, a novel terpene-based high-density biofuel precursor, using engineered Escherichia coli". Renewable Energy. 99: 216–223. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2016.06.061.

- ^ The United States Pharmacopeial Convention. "Revisions to FCC, First Supplement". Archived from the original on 5 July 2010. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ Therapeutic Goods Administration. "Chemical substances" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 April 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2009.