Duloxetine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Cymbalta, Ariclaim, Yentreve, others[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a604030 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ~ 50% (32% to 80%) |

| Protein binding | ~ 95% |

| Metabolism | Liver, two P450 isozymes, CYP2D6 and CYP1A2 |

| Elimination half-life | 12 hours |

| Excretion | 70% in urine, 20% in feces |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI |

|

| ChEMBL |

|

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.116.825 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

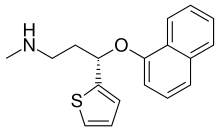

| Formula | C18H19NOS |

| Molar mass | 297.42 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Duloxetine, sold under the brand name Cymbalta among others,[1] is a medication used to treat major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, fibromyalgia, neuropathic pain and central sensitization.[7][8] It is taken by mouth.[7]

Duloxetine is a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI).[9] Similarly to SSRIs and other SNRIs, the precise mechanism for its antidepressant and anxiolytic effects is not known.[7]

Common side effects include dry mouth, nausea, feeling tired, dizziness, agitation, sexual problems, and increased sweating.[7] Severe side effects include an increased risk of suicide, serotonin syndrome, mania, and liver problems.[7] Antidepressant withdrawal syndrome may occur if stopped.[7] There are concerns that use during the later part of pregnancy can harm the developing fetus.[7]

Duloxetine was approved for medical use in the United States and in the European Union in 2004.[5][6][7] It is available as a generic medication.[9] In 2022, it was the 31st most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 18 million prescriptions.[10][11]

Medical uses

[edit]The main uses of duloxetine are in major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, neuropathic pain, chronic musculoskeletal pain, and fibromyalgia.[4][7][12][13]

Duloxetine is recommended as a first-line agent for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced neuropathy by the American Society of Clinical Oncology,[14] as a first-line therapy for fibromyalgia in the presence of mood disorders by the German Interdisciplinary Association for Pain Therapy,[15] as a Grade B recommendation for the treatment of diabetic neuropathy by the American Association for Neurology[16] and as a level A recommendation in certain neuropathic states by the European Federation of Neurological Societies.[17]

Painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy

[edit]A 2014 Cochrane review concluded that duloxetine is beneficial in the treatment of diabetic neuropathy and fibromyalgia but that more comparative studies with other medicines are needed.[18] The French medical journal Prescrire concluded that duloxetine is no better than other available agents and has a greater risk of side effects.[19] Whereas duloxetine has shown efficacy in treating painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy by blocking late Nav 1.7 sodium ion channels and increasing norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine in the CNS and while improving mean NPRS scores and achieving a ≥50% pain response in more patients compared to placebo, it has been associated with potentially serious adverse reactions including hepatotoxicity, serotonin syndrome, severe skin reactions, increased risk of bleeding, increased blood pressure and sexual dysfunction.[20]

Major depressive disorder

[edit]Duloxetine was approved for the treatment of major depression in 2004.[4][5] While duloxetine has demonstrated improvement in depression-related symptoms compared to placebo, comparisons of duloxetine to other antidepressant medications have been less successful. A 2012 Cochrane Review did not find greater efficacy of duloxetine compared to SSRIs and newer antidepressants. Additionally, the review found evidence that duloxetine has increased side effects and reduced tolerability compared to other antidepressants. It thus did not recommend duloxetine as a first line treatment for major depressive disorder, given the (then) high cost of duloxetine compared to inexpensive off-patent antidepressants and lack of increased efficacy.[21] Duloxetine appears less tolerable than some other antidepressants.[22] Generic duloxetine became available in 2013.[23]

Generalized anxiety disorder

[edit]Duloxetine is more effective than placebo in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).[24] A review from the Annals of Internal Medicine lists duloxetine among the first line drug treatments along with citalopram, escitalopram, sertraline, paroxetine, and venlafaxine.[25]

Neuropathic pain

[edit]Duloxetine was approved for the pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) by the US FDA.[26][27][28] The response is achieved in the first two weeks on the medication. Duloxetine slightly increased the fasting serum glucose.[29]

The comparative efficacy of duloxetine and established pain-relief medications for DPN is unclear. A systematic review noted that tricyclic antidepressants (imipramine and amitriptyline), traditional anticonvulsants and opioids have better efficacy than duloxetine. Duloxetine, tricyclic antidepressants and anticonvulsants have similar tolerability while the opioids caused more side effects.[30] Another review in Prescrire International considered the moderate pain relief achieved with duloxetine to be clinically insignificant and the results of the clinical trials unconvincing. The reviewer saw no reason to prescribe duloxetine in practice.[31] The comparative data collected by reviewers in BMC Neurology indicated that amitriptyline, other tricyclic antidepressants and venlafaxine may be more effective. The authors noted that the evidence in favor of duloxetine is much more solid, however.[32] A Cochrane review concluded that the evidence in support of duloxetine's efficacy in treating painful diabetic neuropathy was adequate, and that further trials should focus on comparisons with other medications.[18] A crossover trial found that duloxetine, pregabalin, and amitriptyline offered similar levels of pain relief. Combination treatment of duloxetine and pregabalin offered additional pain relief for people whose pain is not adequately controlled with one medication, and was safe.[33][34]

Duloxetine is also an option for the management of neuropathic pain in multiple sclerosis patients.[35]

Fibromyalgia and chronic pain

[edit]A review of duloxetine found that it reduced pain and fatigue, and improved physical and mental performance compared to placebo.[36]

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the drug for the treatment of fibromyalgia in June 2008.[37][38]

It may be useful for chronic pain from osteoarthritis.[39][40]

On 4 November 2010, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved duloxetine to treat chronic musculoskeletal pain, including discomfort from osteoarthritis and chronic lower back pain.[41][42]

Stress urinary incontinence

[edit]Duloxetine failed to receive US approval for stress urinary incontinence amid concerns over liver toxicity and suicidal events; it was approved for this use in the UK, however, where it is recommended as an add-on medication in stress urinary incontinence instead of surgery.[43]

The safety and utility of duloxetine in the treatment of incontinence has been evaluated in a series of meta analyses and practice guidelines.

- A 2017 meta-analysis found that harms are at least as great if not greater than the benefits.[44]

- A 2013 meta-analysis concluded that duloxetine decreased incontinence episodes more than placebo with people about 56% more likely than placebo to experience a 50% decrease in episodes. Adverse effects were experienced by 83% of duloxetine-treated subjects and by 45% of placebo-treated subjects.[45]

- A 2012 review and practice guideline published by the European Association of Urology concluded that the clinical trial data provides Grade 1a evidence that duloxetine improves but does not cure urinary incontinence, and that it causes a high rate of gastrointestinal side effects (mainly nausea and vomiting) leading to a high rate of treatment discontinuation.[46]

- The National Institute for Clinical and Health Excellence recommends (as of September 2013) that duloxetine not be routinely offered as first line treatment, and that it only be offered as second line therapy in women wishing to avoid therapy. The guideline further states that women should be counseled regarding the drug's side effects.[47]

Contraindications

[edit]The following contraindications are listed by the manufacturer:[48]

- Hypersensitivity: duloxetine is contraindicated in patients with a known hypersensitivity to duloxetine or any of the inactive ingredients.

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs): concomitant use in patients taking MAOIs is contraindicated.

- Uncontrolled narrow-angle glaucoma: in clinical trials, Cymbalta use was associated with an increased risk of mydriasis (dilation of the pupil); therefore, its use should be avoided in patients with uncontrolled narrow-angle glaucoma, in which mydriasis can cause sudden worsening.

- Central nervous system (CNS) acting drugs: given the primary CNS effects of duloxetine, it should be used with caution when it is taken in combination with or substituted for other centrally acting drugs, including those with a similar mechanism of action.

- Duloxetine and thioridazine should not be co-administered.[note 1]

In addition, the FDA has reported on life-threatening drug interactions that may be possible when co-administered with triptans and other drugs acting on serotonin pathways leading to increased risk for serotonin syndrome.[50]

Duloxetine should also be avoided in hepatic impairment such as cirrhosis.[51]

Adverse effects

[edit]Nausea, somnolence, insomnia, and dizziness are the main side effects, reported by about 10% to 20% of patients.[52]

In a trial for major depressive disorder (MDD), the most commonly reported treatment-emergent adverse events among duloxetine-treated patients were nausea (34.7%), dry mouth (22.7%), headache (20.0%) and dizziness (18.7%), and except for headache, these were reported significantly more often than in the placebo group.[53] In a long-term study of fibromyalgia patients receiving duloxetine, frequency and type of adverse effects was similar to that reported in the MDD trial above. Side effects tended to be mild-to-moderate, and tended to decrease in intensity over time.[54][55]

Sexual dysfunction

[edit]In four clinical trials of duloxetine for the treatment of MDD, sexual dysfunction occurred significantly more frequently in patients treated with duloxetine than those treated with placebo, and this difference occurred only in men.[56][55] Specifically, common side effects include difficulty becoming aroused, lack of interest in sex, and anorgasmia (trouble achieving orgasm). Loss of or decreased response to sexual stimuli and ejaculatory anhedonia are also reported.[57] Frequency of treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction were similar for duloxetine and SSRIs when compared in a 6-month observational study in depressed patients.[58] Rates of sexual dysfunction in MDD patients treated with duloxetine versus escitalopram did not differ significantly at 4, 8, and 12 weeks of treatment, although the trend favored duloxetine (33.3% of duloxetine patients experienced sexual side effects compared to 43.6% of those receiving escitalopram and 25% of those receiving placebo).[57]

Increased sweating

[edit]Duloxetine may also cause sweating more than usual (hyperhidrosis).[59][60]

The exact mechanism behind why duloxetine increases sweating is still not fully understood. However, a possible explanation is in duloxetine's action on the sympathetic nervous system. Sympathetic nerves control thermoregulation and sweating in humans; when increased levels of noradrenaline are present (as seen with SNRIs), this can stimulate sweat gland activity, leading to an increase in perspiration. Noradrenaline release may also cause increased serotonin availability that results from inhibiting reuptake enhances and further facilitates the activation of post-synaptic α-adrenoceptors by noradrenaline, which can stimulate sweat gland activity, leading to more significant amounts of copious liquid secretion mainly at higher duloxetine dosages above certain thresholds. The amount of sweating experienced may be influenced by the noradrenergic tone, which is determined by the interaction between noradrenergic and serotonergic neurons.[61][62] Therefore, at higher serum doses or concentrations (above certain thresholds) resulting from therapeutic antidepressant treatment, patients may show more perspiration than at lower doses.[61]

Discontinuation syndrome

[edit]During marketing of other SSRIs and SNRIs, there have been spontaneous reports of adverse events occurring upon discontinuation of these drugs, particularly when abrupt, including the following: dysphoric mood, irritability, agitation, dizziness, sensory disturbances (e.g., paresthesias such as brain zap electric shock sensations), anxiety, confusion, headache, lethargy, emotional lability, insomnia, hypomania, tinnitus, and seizures. The withdrawal syndrome from duloxetine resembles the SSRI discontinuation syndrome.

When discontinuing treatment with duloxetine, the manufacturer recommends a gradual reduction in the dose, rather than abrupt cessation, whenever possible. If intolerable symptoms occur following a decrease in the dose or upon discontinuation of treatment, then resuming the previously prescribed dose may be considered. Subsequently, the physician may continue decreasing the dose but at a more gradual rate.

In placebo-controlled clinical trials of up to nine weeks' duration of patients with MDD, a systematic evaluation of discontinuation symptoms in patients taking duloxetine following abrupt discontinuation found the following symptoms occurring at a rate greater than or equal to 2% and at a significantly higher rate in duloxetine-treated patients compared to those discontinuing from placebo: dizziness, nausea, headache, paresthesia, vomiting, irritability, and nightmare.[63]

In 2012 The Institute for Safe Medical Practices (ISMP) published a report: "Duloxetine and Serious Withdrawal Symptoms". The report highlights early clinical studies which found "abrupt discontinuation showed that withdrawal effects occurred in 40-50% of patients, that 10% of those were severe and approximately half were not resolved when side effects monitoring had ended after one or two weeks".

Withdrawal symptoms listed in 48 case reports (in the first quarter of 2012) included anger, crying, dizziness and suicidal ideation.

The report concluded there was insufficient information and a lack of clear warnings about the effects of discontinuing duloxetine and that in many cases withdrawal symptoms may be "severe, persistent, or both", adding "the prescribing information for physicians and pharmacists does not provide realistic schedules for tapering or a clear picture of the likely incidence of these reactions".

Suicidality

[edit]In the United States all antidepressants, including duloxetine carry a black box warning stating that antidepressants may increase the risk of suicide in persons younger than 25. This warning is based on statistical analyses conducted by two independent groups of the FDA experts that found a 2-fold increase of the suicidal ideation and behavior in children and adolescents, and 1.5-fold increase of suicidality in the 18–24 age group.[64][65][66] To obtain statistically significant results the FDA combined the results of 295 trials of 11 antidepressants for psychiatric indications. As suicidal ideation and behavior in clinical trials are rare, the results for any drug taken separately usually do not reach statistical significance.

In 2005, the United States FDA released a public health advisory noting that there had been eleven reports of suicide attempts and three reports of suicidality within the mostly middle-aged women participating in the open label extension trials of duloxetine for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence (SUI). The FDA described the potential role of confounding social stressors "unclear". The suicide attempt rate in the SUI study population (based on 9,400 patients) was calculated to be 400 per 100,000 person years. This rate is greater than the suicide attempt rate among middle-aged U.S. women that has been reported in published studies, i.e., 150 to 160 per 100,000 person years. In addition, one death from suicide was reported in a Cymbalta clinical pharmacology study in a healthy female volunteer without SUI. No increase in suicidality was reported in controlled trials of Cymbalta for depression or diabetic neuropathic pain.[67]

Postmarketing reports

[edit]Reported adverse events that were temporally correlated to duloxetine therapy include rash, reported rarely, and the following adverse events, reported very rarely: alanine aminotransferase increased, alkaline phosphatase increased, anaphylactic reaction, angioneurotic edema, aspartate aminotransferase increased, bilirubin increased, glaucoma, hepatotoxicity, hyponatremia, jaundice, orthostatic hypotension (especially at the initiation of treatment), Stevens–Johnson syndrome, syncope (especially at initiation of treatment), and urticaria.[68]

Pharmacology

[edit]Mechanism of action

[edit]| Receptor | Ki (nM) |

|---|---|

| SERT | 0.7~0.8 |

| NET | 7.5 |

| DAT | 240 |

| 5-HT2A | 504 |

| 5-HT2C | 916 |

| 5-HT6 | 419 |

Duloxetine inhibits the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine (NE) in the central nervous system. Duloxetine increases dopamine (DA) specifically in the prefrontal cortex, where there are few DA reuptake pumps, via the inhibition of NE reuptake pumps (NET), which is believed to mediate reuptake of DA and NE.[71] Duloxetine has no significant affinity for dopaminergic, cholinergic, histaminergic, opioid, glutamate, and GABA reuptake transporters, however, and can therefore be considered to be a selective reuptake inhibitor at the 5-HT and NE transporters. Duloxetine undergoes extensive metabolism, but the major circulating metabolites do not contribute significantly to the pharmacologic activity.[72][73]

In vitro binding studies using synaptosomal preparations isolated from rat cerebral cortex indicated that duloxetine was approximately 3 fold more potent at inhibiting serotonin uptake than norepinephrine uptake.[74]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Absorption: Duloxetine is acid labile, and is formulated with enteric coating to prevent degradation in the stomach. Duloxetine has good oral bioavailability, averaging 50% after one 60 mg dose. There is an average 2-hour lag until absorption begins with maximum plasma concentrations occurring about 6 hours post dose. Food does not affect the Cmax of duloxetine, but delays the time to reach peak concentration from 6 to 10 hours.[73]

Distribution: Duloxetine is highly bound (>90%) to proteins in human plasma, binding primarily to albumin and α1-acid glycoprotein. Volume of distribution is 1640L.[75]

Metabolism: Duloxetine undergoes predominately hepatic metabolism via two cytochrome P450 isozymes, CYP2D6 and CYP1A2. Circulating metabolites are pharmacologically inactive. Duloxetine is a moderate CYP2D6 inhibitor.[75]

Elimination: Administered in healthy young male subjects at doses between 20 and 40 mg twice a day, had a half-life of 12.5 hours and its pharmacokinetics are dose proportional over the therapeutic range. Steady-state is usually achieved after 3 days. Only trace amounts (<1%) of unchanged duloxetine are present in the urine and most of the dose (approx. 70%) appears in the urine as metabolites of duloxetine with about 20% excreted in the feces.[75]

Smoking is associated with a decrease in duloxetine concentration.[76][77][78]

Research directions

[edit]Major depressive disorder is believed to be due in part to an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines within the central nervous system.[79][80] Antidepressants including ones with a similar mechanism of action as duloxetine, i.e., serotonin metabolism inhibition, cause a decrease in proinflammatory cytokine activity and an increase in anti-inflammatory cytokines;[81] this mechanism may apply to duloxetine in its effect on depression but research on cytokines specific to duloxetine therapy is insufficient.[82][83] Cytokines are immunoregulatory molecules that play a key role in the human immune response. Some cytokines are proinflammatory and contribute to the development of inflammation, while others are anti-inflammatory and help to control the proinflammatory response.[84] Duloxetine can reduce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin 6 (IL-6) and may increase the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin 10 (IL-10), however, mechanisms behind these effects are not well elucidated, there have been mixed findings regarding duloxetine's impact on cytokine production in different contexts, and the results are inconclusive.[85][86][87][88]

Duloxetine is being investigated for its potential to decrease opioid use in the perioperative period because duloxetine administration can help reduce opioid consumption and mitigate the risk of opioid-related side effects and dependence. In total hip arthroplasty (THA) or total knee arthroplasty (TKA), duloxetine is researched to provide pain relief; studies demonstrated that it can reduce pain for several weeks post-surgery without an increased risk of adverse drug events, suggesting that duloxetine could be a valuable component of a multimodal management regimen for patients undergoing THA or TKA.[89] Also, duloxetine can reduce postoperative nausea and vomiting after THA or TKA, which are common side effects of anesthesia and opioids: this additional benefit could improve patient comfort and satisfaction, potentially enhancing recovery outcomes.[89]

History

[edit]

Duloxetine was created by Eli Lilly and Company researchers. David Robertson; David Wong, a co-discoverer of fluoxetine; and Joseph Krushinski are listed as inventors on the patent application filed in 1986 and granted in 1990.[90] The first publication on the discovery of the racemic form of duloxetine known as LY227942, was made in 1988.[91] The (+)-enantiomer, assigned LY248686, was chosen for further studies, because it inhibited serotonin reuptake in rat synaptosomes to twice the degree of the (–)-enantiomer. This molecule was subsequently named duloxetine.[92]

In 2001, Lilly filed a New Drug Application (NDA) for duloxetine with the US Food and Drug Administration. In 2003, however, the FDA "recommended this application as not approvable from the manufacturing and control standpoint" because of "significant cGMP (current Good Manufacturing Practice) violations at the finished product manufacturing facility" of Eli Lilly in Indianapolis. Additionally, "potential liver toxicity" and QTc interval prolongation appeared as a concern. The FDA experts concluded that "duloxetine can cause hepatotoxicity in the form of transaminase elevations. It may also be a factor in causing more severe liver injury, but there are no cases in the NDA database that clearly demonstrate this. Use of duloxetine in the presence of ethanol may potentiate the deleterious effect of ethanol on the liver." The FDA also recommended "routine blood pressure monitoring", since there was a dose-dependant increase in elevated blood pressure readings, including at the new highest recommended dose of 120 mg "where 24% of patients had one or more [elevated] blood pressure readings of 140/90 vs. 9% of placebo patients."[93][94]

After the manufacturing issues were resolved, the liver toxicity warning included in the prescribing information, and the follow-up studies showed that duloxetine does not cause QTc interval prolongation, duloxetine was approved by the FDA for depression and diabetic neuropathy in 2004.[95] In 2007, Health Canada approved duloxetine for the treatment of depression and diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain.[96]

Duloxetine was approved for use of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in the EU in 2004.[6] In 2005, Lilly withdrew the duloxetine application for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in the U.S., stating that discussions with the FDA indicated "the agency is not prepared at this time to grant approval ... based on the data package submitted." A year later Lilly abandoned the pursuit of this indication in the U.S. market.[97][98]

The FDA approved duloxetine for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in February 2007.[99]

Cymbalta generated sales of nearly US$5 billion in 2012, with US$4 billion of that in the U.S., but its patent protection terminated 1 January 2014. Lilly received a six-month extension beyond 30 June 2013, after testing for the treatment of depression in adolescents, which may produce US$1.5 billion in added sales.[100][101]

The first generic duloxetine was marketed by Indian pharmaceutical company Dr. Reddy's Laboratories.[102]

See also

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Duloxetine". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 29 September 2018. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). 31 March 2023. Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ a b c "Cymbalta- duloxetine hydrochloride capsule, delayed release". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ a b c "Cymbalta EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ a b c "Yentreve EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Duloxetine". Monograph. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 26 November 2018. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- ^ "Medications for OCD". International OCD Foundation. Archived from the original on 27 January 2024. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ a b British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. pp. 364–365. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Duloxetine Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical guideline 96: Neuropathic pain – pharmacological management. London, 2010.

- ^ Bril V, England J, Franklin GM, Backonja M, Cohen J, Del Toro D, et al. (May 2011). "Evidence-based guideline: Treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy: report of the American Academy of Neurology, the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine, and the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation". Neurology. 76 (20): 1758–65. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182166ebe. PMC 3100130. PMID 21482920.

- ^ Hershman DL, Lacchetti C, Dworkin RH, Lavoie Smith EM, Bleeker J, Cavaletti G, et al. (June 2014). "Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 32 (18): 1941–1967. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.54.0914. PMID 24733808. S2CID 11183183.

- ^ Sommer C, Häuser W, Alten R, Petzke F, Späth M, Tölle T, et al. (June 2012). "[Drug therapy of fibromyalgia syndrome. Systematic review, meta-analysis and guideline]". Schmerz (in German). 26 (3): 297–310. doi:10.1007/s00482-012-1172-2. PMID 22760463. S2CID 1348989.

- ^ Bril V, England JD, Franklin GM, Backonja M, Cohen JA, Del Toro DR, et al. (June 2011). "Evidence-based guideline: treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy--report of the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine, the American Academy of Neurology, and the American Academy of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation". Muscle & Nerve. 43 (6): 910–7. doi:10.1002/mus.22092. hdl:2027.42/84412. PMID 21484835. S2CID 15020212.

- ^ Attal N, Cruccu G, Baron R, Haanpää M, Hansson P, Jensen TS, et al. (September 2010). "EFNS guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain: 2010 revision". European Journal of Neurology. 17 (9): 1113–e88. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.02999.x. PMID 20402746. S2CID 14236933.

- ^ a b Lunn MP, Hughes RA, Wiffen PJ (January 2014). "Duloxetine for treating painful neuropathy, chronic pain or fibromyalgia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD007115. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007115.pub3. PMC 10711341. PMID 24385423.

- ^ "Towards better patient care: drugs to avoid in 2014". Prescrire International. 23 (150): 161–5. June 2014. PMID 25121155. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ^ Mallick-Searle T, Adler JA (2024). "Update on Treating Painful Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy: A Review of Current US Guidelines with a Focus on the Most Recently Approved Management Options". J Pain Res. 17: 1005–1028. doi:10.2147/JPR.S442595. PMC 10949339. PMID 38505500.

- ^ Cipriani A, Koesters M, Furukawa TA, Nosè M, Purgato M, Omori IM, et al. (October 2012). "Duloxetine versus other anti-depressive agents for depression". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012 (10): CD006533. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006533.pub2. PMC 4169791. PMID 23076926.

- ^ Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Chaimani A, Atkinson LZ, Ogawa Y, et al. (April 2018). "Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". Lancet. 391 (10128): 1357–1366. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7. PMC 5889788. PMID 29477251.

- ^ Swiatek J (13 October 2013). "Loss of Cymbalta patent a major blow for Eli Lilly". Indianapolis Star. Archived from the original on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ^ Carter NJ, McCormack PL (2009). "Duloxetine: a review of its use in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder". CNS Drugs. 23 (6): 523–41. doi:10.2165/00023210-200923060-00006. PMID 19480470. S2CID 30897102.

- ^ Patel G, Fancher TL (December 2013). "Generalized anxiety disorder". Annals of Internal Medicine. 159 (11): ITC6–1, ITC6–2, ITC6–3, ITC6–4, ITC6–5, ITC6–6, ITC6–7, ITC6–8, ITC6–9, ITC6–10, ITC6–11, quiz ITC6–12. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-11-201312030-01006. PMID 24297210. S2CID 42889106.

- ^ Jang HN, Oh TJ (November 2023). "Pharmacological and Nonpharmacological Treatments for Painful Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy". Diabetes Metab J. 47 (6): 743–756. doi:10.4093/dmj.2023.0018. PMC 10695723. PMID 37670573.

- ^ Goldstein DJ, Lu Y, Detke MJ, Lee TC, Iyengar S (July 2005). "Duloxetine vs. placebo in patients with painful diabetic neuropathy". Pain. 116 (1–2): 109–18. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2005.03.029. PMID 15927394. S2CID 10291281.

- ^ Raskin J, Pritchett YL, Wang F, D'Souza DN, Waninger AL, Iyengar S, et al. (2005). "A double-blind, randomized multicenter trial comparing duloxetine with placebo in the management of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain". Pain Medicine. 6 (5): 346–56. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.00061.x. PMID 16266355.

- ^ "Application number 21-733. Medical review(s)" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 3 September 2004. Retrieved 14 April 2009. [dead link]

- ^ Wong MC, Chung JW, Wong TK (July 2007). "Effects of treatments for symptoms of painful diabetic neuropathy: systematic review". BMJ. 335 (7610): 87. doi:10.1136/bmj.39213.565972.AE. PMC 1914460. PMID 17562735.

- ^ "Duloxetine: new indication. Depression and diabetic neuropathy: too many adverse effects". Prescrire International. 15 (85): 168–72. October 2006. PMID 17121211.

- ^ Sultan A, Gaskell H, Derry S, Moore RA (August 2008). "Duloxetine for painful diabetic neuropathy and fibromyalgia pain: systematic review of randomised trials". BMC Neurology. 8: 29. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-8-29. PMC 2529342. PMID 18673529.

- ^ "Combination therapy for painful diabetic neuropathy is safe and effective". NIHR Evidence. 6 April 2023. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_57470. S2CID 258013544. Archived from the original on 28 April 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ Tesfaye S, Sloan G, Petrie J, White D, Bradburn M, Julious S, et al. (August 2022). "Comparison of amitriptyline supplemented with pregabalin, pregabalin supplemented with amitriptyline, and duloxetine supplemented with pregabalin for the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain (OPTION-DM): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised crossover trial". Lancet. 400 (10353): 680–690. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(22)01472-6. PMC 9418415. PMID 36007534.

- ^ Shkodina AD, Bardhan M, Chopra H, Anyagwa OE, Pinchuk VA, Hryn KV, et al. (March 2024). "Pharmacological and Non-pharmacological Approaches for the Management of Neuropathic Pain in Multiple Sclerosis". CNS Drugs. 38 (3): 205–224. doi:10.1007/s40263-024-01072-5. PMID 38421578.

- ^ Acuna C (October 2008). "Duloxetine for the treatment of fibromyalgia". Drugs of Today. 44 (10): 725–34. doi:10.1358/dot.2008.44.10.1269675. PMID 19137126.

- ^ "FDA Approves Cymbalta for the Management of Fibromyalgia". Eli Lilly Co. (Press release). 16 June 2008. Archived from the original on 30 July 2008. Retrieved 17 June 2008.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Cymbalta (duloxetine hydrochloride) NDA #022148". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ Citrome L, Weiss-Citrome A (January 2012). "A systematic review of duloxetine for osteoarthritic pain: what is the number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed?". Postgraduate Medicine. 124 (1): 83–93. doi:10.3810/pgm.2012.01.2521. PMID 22314118. S2CID 20599116.

- ^ Myers J, Wielage RC, Han B, Price K, Gahn J, Paget MA, et al. (March 2014). "The efficacy of duloxetine, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and opioids in osteoarthritis: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis". BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 15: 76. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-15-76. PMC 4007556. PMID 24618328.

- ^ "FDA clears Cymbalta to treat chronic musculoskeletal pain". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). Food and Drug Administration. 4 November 2010. Archived from the original on 7 August 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Cymbalta (duloxetine hydrochloride) NDA #022516". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 16 September 2011. Archived from the original on 5 April 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical guideline 40: Urinary incontinence. London, 2006.

- ^ Maund E, Guski LS, Gøtzsche PC (February 2017). "Considering benefits and harms of duloxetine for treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a meta-analysis of clinical study reports". CMAJ. 189 (5): E194–E203. doi:10.1503/cmaj.151104. PMC 5289870. PMID 28246265.

- ^ Li J, Yang L, Pu C, Tang Y, Yun H, Han P (June 2013). "The role of duloxetine in stress urinary incontinence: a systematic review and meta-analysis". International Urology and Nephrology. 45 (3): 679–86. doi:10.1007/s11255-013-0410-6. PMID 23504618. S2CID 10788312.

- ^ "www.uroweb.org" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 May 2014.

- ^ "Urinary incontinence Introduction CG171". Archived from the original on 4 May 2014.

- ^ "Eli Lilly and Company". Archived from the original on 13 April 2010. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- ^ Derby MA, Zhang L, Chappell JC, Gonzales CR, Callaghan JT, Leibowitz M, et al. (June 2007). "The effects of supratherapeutic doses of duloxetine on blood pressure and pulse rate". Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 49 (6): 384–393. doi:10.1097/FJC.0b013e31804d1cce. PMID 17577103. S2CID 2356196.

- ^ "Information for Healthcare Professionals: Duloxetine (marketed as Cymbalta) – Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) or Selective Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) and 5-Hydroxytryptamine Receptor Agonists (Triptans)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 14 August 2013. Archived from the original on 7 March 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ^ Ma J, Björnsson ES, Chalasani N (February 2024). "The Safe Use of Analgesics in Patients with Cirrhosis: A Narrative Review". Am J Med. 137 (2): 99–106. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2023.10.022. PMID 37918778. S2CID 264888110.

- ^ Cymbalta package insert. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly Pharmaceuticals; 2004, September.

- ^ Perahia DG, Kajdasz DK, Walker DJ, Raskin J, Tylee A (May 2006). "Duloxetine 60 mg once daily in the treatment of milder major depressive disorder". International Journal of Clinical Practice. 60 (5): 613–20. doi:10.1111/j.1368-5031.2006.00956.x. PMC 1473178. PMID 16700869.

- ^ Chappell AS, Littlejohn G, Kajdasz DK, Scheinberg M, D'Souza DN, Moldofsky H (June 2009). "A 1-year safety and efficacy study of duloxetine in patients with fibromyalgia". The Clinical Journal of Pain. 25 (5): 365–75. doi:10.1097/ajp.0b013e31819be587. PMID 19454869. S2CID 12208795.

- ^ a b "Cymbalta - FDA prescribing information, side effects and uses". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ^ Nelson JC, Lu Pritchett Y, Martynov O, Yu JY, Mallinckrodt CH, Detke MJ (2006). "The safety and tolerability of duloxetine compared with paroxetine and placebo: a pooled analysis of 4 clinical trials". Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 8 (4): 212–9. doi:10.4088/pcc.v08n0404. PMC 1557468. PMID 16964316.

- ^ a b Clayton A, Kornstein S, Prakash A, Mallinckrodt C, Wohlreich M (July 2007). "Changes in sexual functioning associated with duloxetine, escitalopram, and placebo in the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 4 (4 Pt 1): 917–29. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00520.x. PMID 17627739.

- ^ Dueñas H, Brnabic AJ, Lee A, Montejo AL, Prakash S, Casimiro-Querubin ML, et al. (November 2011). "Treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction with SSRIs and duloxetine: effectiveness and functional outcomes over a 6-month observational period". International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 15 (4): 242–54. doi:10.3109/13651501.2011.590209. PMID 22121997. S2CID 23153099.

- ^ "Duloxetine (Oral Route) Side Effects - Mayo Clinic". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 19 October 2023. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ Štuhec M (September 2015). "Excessive sweating induced by interaction between agomelatine and duloxetine hydrochloride: case report and review of the literature". Wien Klin Wochenschr. 127 (17–18): 703–6. doi:10.1007/s00508-014-0688-0. PMID 25576334. S2CID 184484229.

- ^ a b Demling J, Beyer S, Kornhuber J (January 2010). "To sweat or not to sweat? A hypothesis on the effects of venlafaxine and SSRIs". Med Hypotheses. 74 (1): 155–7. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2009.07.011. PMID 19664885.

- ^ Idiaquez J, Casar JC, Arnardottir ES, August E, Santin J, Iturriaga R (2023). "Hyperhidrosis in sleep disorders – A narrative review of mechanisms and clinical significance" (PDF). Journal of Sleep Research. 32 (1): e13660. doi:10.1111/jsr.13660. hdl:20.500.11815/4065. PMID 35706374.

- ^ Perahia DG, Kajdasz DK, Desaiah D, Haddad PM (December 2005). "Symptoms following abrupt discontinuation of duloxetine treatment in patients with major depressive disorder". Journal of Affective Disorders. 89 (1–3): 207–12. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2005.09.003. PMID 16266753.

- ^ Levenson M, Holland C. "Antidepressants and Suicidality in Adults: Statistical Evaluation. (Presentation at Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee; December 13, 2006)". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 13 May 2007.

- ^ Stone MB, Jones ML (17 November 2006). "Clinical review: relationship between antidepressant drugs and suicidality in adults" (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). pp. 11–74. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 March 2007. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- ^ Levenson M, Holland C (17 November 2006). "Statistical Evaluation of Suicidality in Adults Treated with Antidepressants" (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). pp. 75–140. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 March 2007. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- ^ "Historical Information on Duloxetine hydrochloride (marketed as Cymbalta)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 22 July 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ "Duloxetine Side Effects, and Drug Interactions". RxList Monographs. Archived from the original on 12 September 2008.

- ^ Bymaster FP, Dreshfield-Ahmad LJ, Threlkeld PG, Shaw JL, Thompson L, Nelson DL, et al. (December 2001). "Comparative affinity of duloxetine and venlafaxine for serotonin and norepinephrine transporters in vitro and in vivo, human serotonin receptor subtypes, and other neuronal receptors". Neuropsychopharmacology. 25 (6): 871–80. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00298-6. PMID 11750180.

- ^ Li JJ (2015). Top Drugs: Their History, Pharmacology, and Syntheses. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-936258-5. Archived from the original on 25 February 2024. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ Stahl S (2013). Stahl's Essential Pharmacology (4th ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 305, 308, 309.

- ^ Stahl SM, Grady MM, Moret C, Briley M (September 2005). "SNRIs: their pharmacology, clinical efficacy, and tolerability in comparison with other classes of antidepressants". CNS Spectrums. 10 (9): 732–47. doi:10.1017/s1092852900019726. PMID 16142213. S2CID 40022100.

- ^ a b Bymaster FP, Lee TC, Knadler MP, Detke MJ, Iyengar S (2005). "The dual transporter inhibitor duloxetine: a review of its preclinical pharmacology, pharmacokinetic profile, and clinical results in depression". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 11 (12): 1475–93. doi:10.2174/1381612053764805. PMID 15892657.

- ^ Onuţu AH (October 2015). "Duloxetine, an antidepressant with analgesic properties - a preliminary analysis". Romanian Journal of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. 22 (2): 123–128. PMC 5505372. PMID 28913467.

- ^ a b c "Cymbalta product insert" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 October 2005. Retrieved 1 November 2005.

- ^ Knadler MP, Lobo E, Chappell J, Bergstrom R (May 2011). "Duloxetine: clinical pharmacokinetics and drug interactions". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 50 (5): 281–294. doi:10.2165/11539240-000000000-00000. PMID 21366359. S2CID 207299455.

- ^ Fric M, Pfuhlmann B, Laux G, Riederer P, Distler G, Artmann S, et al. (July 2008). "The influence of smoking on the serum level of duloxetine". Pharmacopsychiatry. 41 (4): 151–155. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1073173. PMID 18651344. S2CID 22045964.

- ^ "Duloxetine 60mg gastro-resistant capsules - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (emc)". www.medicines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ Lotrich FE (August 2015). "Inflammatory cytokine-associated depression". Brain Res. 1617: 113–25. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2014.06.032. PMC 4284141. PMID 25003554.

- ^ Kim YK, Na KS, Shin KH, Jung HY, Choi SH, Kim JB (June 2007). "Cytokine imbalance in the pathophysiology of major depressive disorder". Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 31 (5): 1044–53. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.03.004. PMID 17433516. S2CID 22275879.

- ^ Fornaro M, Rocchi G, Escelsior A, Contini P, Martino M (March 2013). "Might different cytokine trends in depressed patients receiving duloxetine indicate differential biological backgrounds". J Affect Disord. 145 (3): 300–7. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2012.08.007. PMID 22981313.

- ^ De Berardis D, Conti CM, Serroni N, Moschetta FS, Olivieri L, Carano A, et al. (2010). "The effect of newer serotonin-noradrenalin antidepressants on cytokine production: a review of the current literature". International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology. 23 (2): 417–22. doi:10.1177/039463201002300204. PMID 20646337. S2CID 656023.

- ^ Hannestad J, DellaGioia N, Bloch M (November 2011). "The Effect of Antidepressant Medication Treatment on Serum Levels of Inflammatory Cytokines: A Meta-Analysis". Neuropsychopharmacology. 36 (12): 2452–59. doi:10.1038/npp.2011.132. PMC 3194072. PMID 21796103.

- ^ Opal SM, DePalo VA (April 2000). "Anti-inflammatory cytokines". Chest. 117 (4): 1162–72. doi:10.1378/chest.117.4.1162. PMID 10767254. S2CID 2267250.

- ^ Zhu J, Chen J, Zhang K (August 2022). "Clinical effect of flunarizine combined with duloxetine in the treatment of chronic migraine comorbidity of depression and anxiety disorder". Brain Behav. 12 (8): e2689. doi:10.1002/brb3.2689. PMC 9392519. PMID 35791513.

- ^ Maciukiewicz M, Marshe VS, Tiwari AK, Fonseka TM, Freeman N, Rotzinger S, et al. (November 2015). "Genetic variation in IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, TSPO and BDNF and response to duloxetine or placebo treatment in major depressive disorder". Pharmacogenomics. 16 (17): 1919–29. doi:10.2217/pgs.15.136. PMID 26556688.

- ^ Miyauchi T, Tokura T, Kimura H, Ito M, Umemura E, Sato Boku A, et al. (July 2019). "Effect of antidepressant treatment on plasma levels of neuroinflammation-associated molecules in patients with somatic symptom disorder with predominant pain around the orofacial region". Hum Psychopharmacol. 34 (4): e2698. doi:10.1002/hup.2698. PMID 31125145. S2CID 163168228.

- ^ Qiu W, Go KA, Wen Y, Duarte-Guterman P, Eid RS, Galea LAM (October 2021). "Maternal fluoxetine reduces hippocampal inflammation and neurogenesis in adult offspring with sex-specific effects of periadolescent oxytocin". Brain Behav Immun. 97: 394–409. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2021.06.012. PMID 34174336. S2CID 235620244.

- ^ a b Lin Y, Jiang M, Liao C, Wu Q, Zhao J (March 2024). "Duloxetine reduces opioid consumption and pain after total hip or knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". J Orthop Surg Res. 19 (1): 181. doi:10.1186/s13018-024-04648-5. PMC 10936099. PMID 38481321.

- ^ Robertson DW, Wong DT, Krushinski JH (11 September 1990). "United States Patent 4,956,388: 3-Aryloxy-3-substituted propanamines". USPTO. Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- ^ Wong DT, Robertson DW, Bymaster FP, Krushinski JH, Reid LR (1988). "LY227942, an inhibitor of serotonin and norepinephrine uptake: biochemical pharmacology of a potential antidepressant drug". Life Sciences. 43 (24): 2049–57. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(88)90579-6. PMID 2850421.

- ^ Bymaster FP, Beedle EE, Findlay J, Gallagher PT, Krushinski JH, Mitchell S, et al. (December 2003). "Duloxetine (Cymbalta), a dual inhibitor of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 13 (24): 4477–80. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.08.079. PMID 14643350.

- ^ Approval package for: application number NDA 721-427. Administrative/Correspondence #2 (PDF) (Report). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 February 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2008.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Cymbalta (Duloxetine Hydrochloride) NDA #021427". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 24 December 1999. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ "FDA news". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 13 May 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ "Summary Basis of Decision (SBD): Cymbalta". Health Canada. 5 May 2008. Archived from the original on 1 March 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ^ "Lilly Won't Pursue Yentreve for U.S." TheStreet.com. 15 February 2006. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 18 May 2008.

- ^ Lenzer J (July 2005). "FDA warns that antidepressants may increase suicidality in adults". BMJ. 331 (7508): 70. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7508.70-b. PMC 558648. PMID 16002878.

- ^ "FDA approves antidepressant Cymbalta (duloxetine HCl) for treatment of generalized anxiety disorder". News-Medical. 26 February 2007. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- ^ Staton T (9 July 2012). "Lilly could net $1.5B-plus from Cymbalta extension". FiercePharma. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- ^ Palmer E (11 April 2013). "Eli Lilly to lay off hundreds in sales as Cymbalta nears edge of patent cliff". FiercePharma. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- ^ Anson P (12 December 2013). "Generic Cheaper Versions of Cymbalta Approved". National Pain Report. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2014.