Wikipedia:WikiProject Squatting/Draft/Squatting in Africa

Squatting in Africa

Overview

[edit]During the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa, concern was expressed about the impact upon people living in informal settlements across the continent.[1]

Country

[edit]Algeria

[edit]In Algeria, the high cost of housing leads to informal settlements, many of which are on squatted land.[2] Migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa head to Algeria and settle in informal settlements. Many gather at the southernb city of Tamanrasset.[3]

Angola

[edit]Squatting in Angola occurs when displaced peoples occupy informal settlements in coastal cities such as the capital Luanda. These are known as musseques and 55 per cent have electricity and 12.4 per cent have running water.[4] The Government of Angola has been criticized by Amnesty International and Christian Aid for forcibly evicting squatters and not resettling them.[5]

Benin

[edit]- Squatting in Benin

Botswana

[edit]Botswana was not developed under colonialism and was administered from Mafeking in south Africa. After independence in 1966, it had minimal infrastructure and a small population. Over the next 20 years its economy grew rapidly as a result of the mining of minerals and diamonds.[6] Land use is customary and each citizen can receive a plot with land for free, meaning that informal settlements were not established as much as in many other African countries, although some were established after independence around Francistown and the capital Gaborone where the Old Naledi area has subsequently been upgraded.[6][7]

The San people are hunter gatherers who have been displaced from their traditional territories which are being turned into commercial ranches. They then become squatters on these lands. In 1989 there were an estimated 40,000 San people living in Botswana, although when interviewed they did not know the name of the country.[8] As of 2001, 61 per cent of the population was living in slums.[9]

- Shabane, Ikopoleng; Nkambwe, Musisi; Chanda, Raban (1 April 2011). "Landuse, policy, and squatter settlements: The case of peri-urban areas in Botswana". Applied Geography. 31 (2): 677–686. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2010.03.004.

Burkina Faso

[edit]Burkina Faso is a poor country and as of 2002, 90% of the population was practicing subsistence agriculture.[10] It is urbanizing at a slower rate than its neighbours and as people move to the cities, the lack of affordable housing and bad governance lead to informal settlements.[11] The government has begun a housing program which was expected to build 40,000 new homes between 2016 and 2020.[11]

Slum upgrading projects were begun by UNDP and UN-Habitat in 1974. Sanitation and running water are important issues. In 2002, 22% of the capital Ouagadougou had running water, mainly in the centre. The percentage for the informal settlements was 0.5%.[10] The World Bank reported in 2017 that after over 15 years of aid work, access to running water and sanitation was still difficult for many.[12] People in Ouagadougou's slums are poor and uneducated, but child vaccination rates are higher than in the informal settlements of Nairobi in Kenya.[13]

Burundi

[edit]Since becoming a republic in 1962, Burundi regards unoccupied land as owned by the state and all occupied land is in theory registered under the 1986 Land Tenure Code.[14] In 2016, the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes made a judgement in Joseph Houben v Burundi against the state. Houben had bought 14 acres of land in 2005, which were then squatted. The local authorities had encouraged the squatters, resulting in the courtcase.[15] The Batwa (or Twa) people make up 1 per cent of the population.[16] They are traditionally hunter gatherers and much of their customary land has been taken by other ethnic groups, leading them to squat on their former lands.[17]

Cameroon

[edit]In Cameroon, land can be broken into three categories: it is either private, public or national land (domaine nationale). The latter is unregistered land, which makes up most of the countryside and 90 per cent of the total land mass. Land use is governed by Ordinance No. 74-1 (1974). Only one in twenty households have title to their land, and most people can be considered squatters in that they have no legal ownership of the land they live on.[18] The Bimbia-Bonadikombo community forest in the Mount Cameroon forest area was set up as a means to protect the forest for the indigenous peoples living there who regarded other users as squatters.[19] Flooding displaced over 80,000 people from informal settlements in the Douala V area of Douala in 2015.[20] In 2019, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development joined with UN-Habitat to house people living in slums and squatter settlements.[21]

Central African Republic

[edit]Squatting in Central African Republic

Chad

[edit]Squatting in Chad

Comoros

[edit]- https://unhabitat.org/comoros

- https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/pdf/10.1596/35115

- https://www.equaltimes.org/in-mayotte-the-french-state-is?lang=en#.Y8KBVf7P02w

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0013795210000992

Côte d'Ivoire

[edit]As the capital Abidjan grew, the districts of Adobo and Yopougon were expanded by squatters.[22] The 1998 Land Law mandated the registering and titling of rural land.[23] The government has sporadically evicted squatters from national parks and forests in an attempt to stop illegal logging.[24] Human Rights Watch criticized the manner in which this policy was pursued.[25] During the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa, squatters in the hospital at Cocody were evicted so that patients could be treated; they had been there since the Second Ivorian Civil War in 2011.[26]

Democratic Republic of the Congo

[edit]Squatting in Democratic Republic of the Congo

Djibouti

[edit]Squatting in Djibouti

Egypt

[edit]- CURRENTLY AT SQUATTING: The City of the Dead slum is a well-known squatter community in Cairo, Egypt.[27] Between 1955 and 1975, the Cairo authorities built 39,000 public housing apartments but 2 million people moved there, mostly ending up in informal housing. In Alexandria, Egypt's second city, public housing was only 0.5% of the total housing stock, whereas informal housing was 68%.[28]: 108

- https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Knowledge_Based_Urban_Development_in_the/xw9MDwAAQBAJ page124

Equatorial Guinea

[edit]Squatting in Equatorial Guinea

Eritrea

[edit]Eritrea was an Italian colony between 1890 and 1942. It then gained independence in the 1990s after the Eritrean War of Independence which was fought against Ethiopia. A cadastre was first set up in 1888 by the Italians.[29] The uncontested possession of land for forty year was recognized in 1934 as allowing adverse possession and was known as "deqi arba'a". Another form of squatters rights in certain parts of the country was "kwah mahtse" which translates as "stroke of the axe" which refers to the act of clearing overgrown land prior to occupation.[30] This occurred only in the provinces of Akele Guzai and Serae and could only be practiced by local people; if they then left the land unused for one agricultural season, the right of possession would collapse.[31]

The Commission for the Verification of Houses was founded in 1992, in order to return property which had been nationalized by the Derg. In some cases houses were squatted.[29] In recent years, thousands of people live in informal settlements surrounding cities and towns.[30]

Eswatini

[edit]- "Squatters" who were workers on farms owned by European settler colonialists.[32]: 230 There were estimated to be around 13,000 such squatters in 1960, in a study by the Institute for Social Research, University of Natal.[32]: 371

- List of slums in Eswatini

- Swazi Nation Land

- -

- https://www.ipsnews.net/2006/12/development-swaziland-squatters-make-communities-out-of-chaos/

- Murray Camp http://www.times.co.sz/News/67598.html and http://www.times.co.sz/feature/80056-murray-camp-evictions-loom.html

- Esthomo near Malkernhttps://www.ippmedia.com/en/features/swaziland-fear-witches

- Squatting as an Epiphenomenon: The Evolution of Unplanned Settlement in Swaziland - John P. Lea

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0277953684901679

- https://www.ajol.info/index.php/rosas/article/view/22988

- https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/9780230288485_6

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03057079108708299

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/2636526

Ethiopia

[edit]- Abagissa, Jemal (2019). "INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS IN ADDIS ABABA: EXTENT, CHALLENGES AND MEASURES TAKEN". Journal of Public Administration, Finance and Law (15): 7–30. ISSN 2285-2204.

Gabon

[edit]The population of Libreville has grown from 150,000 in the 1970s, to 330,000 in 1990 and almost 600,000 by 2006. This has led to squatters creating informal settlements.[33] In Libreville, thousands of disabled squatters occupy buildings and are represented by the Association of Motorically Handicapped People of Gabon (ANPHMG).[34]

Gambia

[edit]Squatting in Gambia

Ghana

[edit]In Ghana, informal settlements are found in cities such as Kumasi and the capital Accra. Ashaiman, now a town of 100,000 people, was swelled by squatters. In central Accra, next to Agbogbloshie, the Old Fadama settlement houses an estimated 80,000 people and is subject to a controversial discussion about eviction. The residents have been supported by Amnesty International, the Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions and Shack Dwellers International.

Guinea-Bissau

[edit]Squatting in Guinea-Bissau

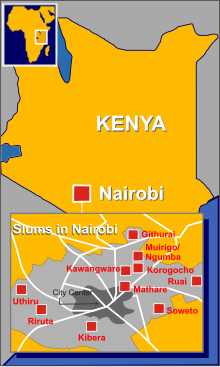

Kenya

[edit]

- File:Statue of Dedan Kimathi Nairobi, Kenya.jpg

- Nandi

- https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=vD-ZqX4pbbYC&pg=PA508

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/african-studies-review/article/asr-volume-23-issue-3-cover-and-back-matter/46BFEA182661BCC79CFC864955042267

- Kichinjio

Lesotho

[edit]- Squatting in Lesotho

- Most towns in Lesotho were established in colonial times as administrative outposts and have developed into urban centres, often ringed by informal settlements, which grow through both squatting and illegal subdivisioning of land.[35][36] For example, in 1992 Maputsoe had 11,200 official inhabitants and 18,000 living in slums, giving it a total population of 29,000.[36]

- In the 1970s, the government did not recognise the issue of squatting, seeing it only as a transitory phenomenon. The capital Maseru grew rapildy,, with peripheral settlements such as Borokhoaneng, Lithabaneng, Mabote, Motimposo, Qoaling, Sebaboleng and Thamaes eventually becoming part of the city.[35]

- The 1979 Land Act established three forms of land tenure, namely leasehold, allocation and licence. It was enacted after the World Bank threatened to withdraw funding for housing projects.[37]: 6, 9 This was then superseded by the 2010 Land Act.[37]: 9–13

Liberia

[edit]

In Liberia, squatting is one of three ways to access land, the other being ownership by deed or customary ownership.[38] West Point was founded in Monrovia in the 1950s and is estimated to house between 29,500 and 75,000 people.[39] During the First Liberian Civil War 1989–1997 and the Second Liberian Civil War 1999–2003, many people in Liberia were displaced and some ended up squatting in Monrovia.[40] The Ducor Hotel fell into disrepair and was squatted, before being evicted in 2007.[41] Recently, over 9,000 Burkinabés were squatting on remote land and the Liberia Land Authority (LLA) has announced it will be titling all land in the country.[42][43]

Libya

[edit]Libya's capital Tripoli began to experience squatted informal settlements in the 1980s as internal migration brought people to the cities.[44] Also in the 1980s, an estimated 19% of farms across the country were squatted.[45]: 3 During the Second Libyan Civil War (2014-2020), forces led by Khalifa Haftar attacked Tripoli in 2019 and over 140,000 residents were forced out of their homes. Some of them squatted in unfinished buildings in other parts of the city.[46] As of 2020, there were still many people squatting as a result of being displaced.[47]

- 1986 https://www.upi.com/Archives/1986/07/07/Former-Libyan-embassy-now-a-haven-for-squatters/8814521092800/

- International reactions to the 2011 Libyan Civil War

- https://foreignpolicy.com/2011/04/28/saif-house-2/

- https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2011/mar/11/radical-squat-gaddafi-mansion

Madagascar

[edit]In Madagascar, land titled in colonial times has since been left derelict and then squatted, for example in the area around Ankijabe.[48] The 2005 land laws intended to protect local land rights are not enforced, since state representatives prefer to sell land to foreign companies.[49] Adverse possession of a titled building can occur after twenty years of possession by a Malagasy national or thirty years by a foreigner.[50]

Farmers who have farmed land for generations but have no legal title are viewed as squatters by the state. Occasionally, such as in the sale of land destined to be part of the Ambatovy mine, the owner has included the farmers in the deal.[51] At a Chinese-owned sugarcane plantation in Morondava, the company permitted workers to farm land and numbers swelled until there were 5,000 squatters.[52]

Malawi

[edit]

- Squatting in Malawi

- Land ownership in Malawi is either private, public or customary. In addition, around 21 percent of the total land mass holds protected status, being reserves or national parks.The Matandwe Forest Reserve was occupied in 1994; by 2002, there were 5,000 peasant squatters and when 200 were convicted of trespass, the rest vowed to resist eviction. Elsewhere in the country, tea plantations and tobacco farms have also been squatted.[53]

Mali

[edit]Squatting in Mali has resulted from internal migration to cities such as the capital Bamako and Ségou.[54][55] Bamako was founded on the banks of the Niger river during French colonialism and has expanded along the plain, absorbing informal settlements.[56] Squatters formed 25% of the total urban population of Bamako in 1976, and by 1987 the figure had risen to 40%.[57][56] When Mali became independent in 1960, the state maintained the colonial practice of owning all land. The Code Domanial et Foncier of 1986 then introduced land rights and the Agricultural Land Tenure Law was promulgated in 2017. A cadastre for Mali was first formulated in 2014.[54]

Mauritania

[edit]The Constitution of Mauritania was adopted in 1991 and guarantees private property rights. Other relevant laws are the 1983 Land Tenure Act and the Urbanism Code. It is difficult for women to own property, under 8% of 27,000 title deeds are held by females. [58] In Mauritania there are squatter districts in all cities, including the capital Nouakchott. The International Monetary Fund reported that in 2008 there were an estimated 194,000 squatters in Nouakchott.[59] It was created in 1958 with 500 inhabitants and has grown to be a city of over one million inhabitants. Many internal migrants moved to the capital to escape droughts in the 1970s and 1980s. They lived in informal settlements and when the authorities gave them title to the land, they would often sell the plot and start squatting again somewhere else.[60]

Squats are known as "gazra", referring to the unauthorized occupation of land or buildings. Most inhabitants are Arab-Berber and some are not poor but rather speculators waiting to make money when their land title is legalized. Up until 2008, the Arafat gazra in the city centre was home to 85,000 people. There is also the separate phenomenon of the "kebbe" or slum, where mostly Haratin ex-nomads live in tents. The quickest route towards the acquisition of title to land is often an informal practice known as "tieb tieb".[60]

Mauritius

[edit]

The island country of Mauritius was a British colony until 1968.

Squatting was made illegal by an order in 1838, but after emancipation in 1839, former slaves squatted land and in some cases were able to buy their plots, in for example Mahébourg, Pointe des Lascar, Poudre d'Or, Souillac and Trou aux Biches. A Crown Land Commission Report in 1872 stated that there were around 1,097 squatting households, half of which were in the capital Port Louis. Most of these rural squatters were extremely poor.[61][62]

- 1835 emancipation https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03057070.2021.1899465

In 2010, the Mauritius Times described squatting as "endemic in our socio-political system".[63]

During the COVID-19 pandemic in Mauritius, squatters occupied plots on state-owned land in Curepipe, Le Morne, Riambel and Pointe aux Sables in Port Louis.[64] The Government of Mauritius evicted the squatters and promised to rehouse them.[64] Fifteen months later there were still four families squatting at Pointe aux Sables.[65]

Morocco

[edit]Under the French Protectorate in Morocco (1912-1956), the country urbanized and rural migrants moved to the cities, establishing shanty towns known as bidonvilles. They were constructed from recycled materials such as wood and flattened oil drums. The French provided no utilities and so the bidonvilles became unhealthy.[66] Some were squatted, others were built on land to which the inhabitants had title. By 1983, an estimated 30% of the urban population were squatters.[67] Slums increased at 6% per year between 1992 and 2001, and as part of a slum upgrading program, the Moroccan government introduced the Villes Sans Bidonvilles (VSB, Towns without shanty towns) project in 2004.[68] In the Ennakhil slum in Grand Casablanca, around 5,000 inhabitants lived in shacks or a derelict army barracks. VSB, supported by King Mohamed VI, consulted the community and relocated households to new apartment buildings from 2008 onwards.[68] As part of the European migrant crisis in the 2010s, migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa would squat in Morocco as they attempted to reach Spain, or the two Spanish enclaves in Morocco, Ceuta and Mellila.[69]

Mozambique

[edit]

By 1994, an estimated 40 million hectares of land (over half of Mozambique's total land mass) had been sold or given to commercial interests. This had led to many smallholders being displaced and in some cases then squatting the land they had previously occupied.[70] In the 1990s, Mozambican smallholder farming migrants crossed the border into Zimbabwe and entered into Zimbabwean territorial disputes, sometimes squatting.[71] In the 2000s, the flow was reversed when large-scale commercial farming White Zimbabweans moved onto land in Manica Province and occasionally evicted squatters.[72]

Grande Hotel Beira is a former luxury hotel in Beira that fell derelict and after the Mozambican Civil War was occupied by an estimated 3,500 squatters.[73] The film Night Lodgers is a 2007 documentary about the residents.[74]

- Jenkins, Paul (September 2001). "Strengthening Access to Land for Housing for the Poor in Maputo, Mozambique". International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 25 (3): 629–648. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.00333.

Namibia

[edit]Indigenous Namibians squatted during World War I, then were forcibly resettled under apartheid when South Africa ruled what was then known as South West Africa. After Namibian independence in 1990, squatting increased as people migrated to cities such as Windhoek, Otjiwarongo and Oshakati. By 2020, 401,748 people were living in 113 informal settlements across the country.

Nigeria

[edit]In Nigeria, squatters migrate from the countryside to informal settlements in cities such as Abuja, Port Harcourt and in particular Lagos.[75][76] Lagos had a population of over 14 million people in 2019 and many slums, including Makoko which houses anything between 40,000 and 300,000 people.[77][78]

Niger

[edit]- https://reliefweb.int/report/niger/niger-flood-victims-continue-crowding-city-schools

- https://sg.news.yahoo.com/niger-capitals-green-lung-facing-suffocation-062517982.html

- https://reliefweb.int/report/niger/after-ten-years-armed-violence-sahel-there-still-time-humanity

- https://floodlist.com/africa/west-central-africa-floods-august-2022

Republic of the Congo

[edit]- Squatting in the Republic of the Congo

- 10.1177/000203971605100103

Rwanda

[edit]Following the Rwandan Civil War and genocide, many displaced people squatted abandoned houses.[79] By 1996, a law had been passed enabling an estimated 600,000 returning refugees to reclaim their property.[80]

Senegal

[edit]

In 2014, 2.5 million people in Senegal were living in slums. At Guinaw Rails Nord, an informal settlement in the Pikine Department, residents have successfully resisted eviction for decades.[81] Dalifort is another settlement in Pikine, which was set up in the 1950s partly on customary land and partly on land squatted from French owner. In 2007, it had a population of over 6,000.[82] Under Law 64–46, the government can evict squatters without compensation if the land is required for public works and customary land was transferred to the state.[81][82]

Sierra Leone

[edit]Following the Sierra Leone 1991-2002 civil war, displaced people and returning combatants squatted in places such as mining concerns.[83][84] During the COVID-19 pandemic in Sierra Leone, although the country had recorded a relatively low number of cases by November 2020, concern was expressed that inhabitants of informal settlements would be hard hit owing to overcrowding and the lack of fresh running water. The 2014 Ebola virus epidemic in Sierra Leone had affected those in settlements at a dispropotionately high level.[1]

In recent years, squatting has proliferated in the Western Area which includes the capital Freetown.[85] After being threatened with eviction in 2013, squatters in the city of Waterloo attacked a police station with machetes and sticks.[86]

- Njoh, Ambe J.; Akiwumi, Fenda (April 2012). "Colonial legacies, land policies and the millennium development goals: Lessons from Cameroon and Sierra Leone". Habitat International. 36 (2): 210–218. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2011.08.002.

Somalia

[edit]- https://intpolicydigest.org/sixty-years-on-a-new-dawn-for-somalia

- https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/01/28/somalia-thousands-homeless-settlements-razed

- https://thesomalidigest.com/dabdamiska-crisis-exposes-somali-governments-clan-loyalty-challenges/

- Dervish movement (Somali)

- Somali Civil War

- War in Somalia (2006–2009)

- Somali civil war (2009–present)

During the Somali civil war (2009–present) many people have been killed or displaced from their homes. This has resulted in increasing urbanisation, since people migrated for safety to informal settlements on the periphery of the capital Mogadishu; in 2016, UNHCR recorded 400,000 internally displaced people, out of a total population of 1.5 million.[87] Following the establishment of the Federal Government of Somalia in 2012, evictions of settlements increased as the city was slowly redeveloped. That year, over 50,000 people squatting in government buildings were evicted and around 35,000 people were evicted in 2017 from the Deynille and Kahda areas of Mogadishu.[87][88] In 2020, the number of people in the informal settlements again swelled to over 800,000 after conflict and also famine.[89]

South Africa

[edit]- Squatting in South Africa - currently redirects to Squatting

History

[edit]Under British colonialism, African labourers working on white settler farms were known as "squatters". This phenomenon also occurred in Southern Rhodesia and Kenya; by the time of World War I, there were over one million such squatters in South Africa.[90]

Under apartheid, bantustans were created as enclaves for specific ethnic groups. In the 1970s, a squatted zone called Kromdraai formed at Thaba 'Nchu in what was then the Bophuthatswana bantustan.[91]

21st-century

[edit]In the 21st-century, South Africa

Notes

[edit]- https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/EJC93982

- Prevention of Illegal Squatting Act, 1951

- Apartheid

- Haenertsburg

- AbM

- Ponte City

- Kennedy Road

- Marikana

- Mfecane

See also

[edit]South Sudan

[edit]- https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/9781003021636-19/community-response-land-conflicts-transitional-constitution-south-sudan-justin-tata

- https://reliefweb.int/report/sudan/displacement-conflict-and-socio-cultural-survival-southern-sudan

A 2014 report by the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) found that three informal settlements in the capital Juba were all founded through squatting and later rent was imposed by force, often by members of the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA).[92]

Sudan

[edit]Squatting in Sudan is defined as the "acquisition and construction of land, within the city boundaries for the purpose of housing in contradiction to Urban Planning and Land laws and building regulations."[93] These informal settlements arose in Khartoum from the 1920s onwards, swelling in the 1960s. By the 1980s, the government was clearing settlements in Khartoum and regularizing them elsewhere. It was estimated that in 2015 that were 200,000 squatters in Khartoum, 180,000 in Nyala, 60,000 in Kassala, 70,000 in Port Sudan and 170,000 in Wad Madani.[93]

Tanzania

[edit]After independence in 1963 urban land in Tanzania was nationalised.[94] Whilst under colonialism informal construction in the capital Dar es Salaam had been tolerated on rented land, following independence squatting increased dramatically.[94] Houses built by squatters were in traditional Swahili style and sometimes were in better condition than those built on rented land. They were made out of mud, thatch, concrete and metal.[95] By 1975, there were over 20 squatter areas in Dar es Salaam and one (Manzese) had a population of around 90,000.[94]

Togo

[edit]Squatting in Togo

Tunisia

[edit]Informal settlements known as "gourbivilles" sprang up in the French protectorate of Tunisia in the 1930s and again after World War II.[96][97] From the 1960s onwards, areas of land on the periphery of cities were either bought or squatted, and the new inhabitants built housing for themselves, sometimes creating new suburbs with bad infrastructure. By 1980, the country had 210 informal settlements housing around 500,000 people (28 per cent of the population of urban zones).[97]

Uganda

[edit]Yemen

[edit]In the 1990s, squatted informal settlements emerged in Sanaa and other cities. One such squat was Dār Salm in the south of Sanaa. The settlements provided shelter for the poor, including the muhammashīn (literally the marginalized) who are low caste workers.[98]

- https://www.arabnews.com/node/1792921/middle-east

- https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/dec/21/yemen-uae-united-arab-emirates-profiting-from-chaos-of-civil-war

- https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna41874976

- https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-clashes/squatters-police-clash-in-south-yemen-2-killed-idUSTRE7213KA20110302

- Arab Spring

Zambia

[edit]Squatting in Zambia - also Komboni

Zimbabwe

[edit]Land squats occurred in what would become Zimbabwe in the 1970s and were routinely evicted. Only Epworth persisted on account of its size (around 50,000 people).[99] After Zimbabwe was created in 1980, peasant farmers and squatters disputed the distribution of land. Informal settlements have developed on the periphery of cities such as Chitungwiza and the capital Harare.[100] In 2005, Operation Murambatsvina ("Operation Drive Out Filth") organised by President Robert Mugabe evicted an estimated 700,000 people and affected over two million people.[101]

- Mabvuku

- Mbare, Harare

- Waterfalls, Harare

- Kuwadzana

- Budiriro

- Glen Norah, Harare

- Land reform in Zimbabwe

- https://archive.org/details/weareeverywheren00raeb/page/189/mode/2up

See also

[edit]- Wikipedia:WikiProject Squatting/Draft/Squatting in Asia

- Wikipedia:WikiProject Squatting/Draft/Squatting in Europe

- Wikipedia:WikiProject Squatting/Draft/Squatting in North America

- Wikipedia:WikiProject Squatting/Draft/Squatting in Oceania

- Wikipedia:WikiProject Squatting/Draft/Squatting in South America

References

[edit]- ^ a b Osuteye, Emmanuel; Koroma, Braima; Macarthy, Joseph Mustapha; Kamara, Sulaiman Foday; Conteh, Abu (31 December 2020). "Fighting COVID-19 in Freetown, Sierra Leone: the critical role of community organisations in a growing pandemic". Open Health. 1 (1): 51–63. doi:10.1515/openhe-2020-0005.

- ^ Bellal, Tahar (2009). "Housing supply in Algeria: Affordability matters rather than availability" (PDF). Theoretical and Empirical Researches in Urban Management. 3 (12): 109–110.

- ^ Farrah, Raouf (2020). "Algeria's Migration Dilemma" (PDF). Global Initiative. p. 17. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Barros, Carlos Pestana; Balsas, Carlos J. L. (2019). "Luanda's Slums: An overview based on poverty and gentrification". Urban Development Issues. 64 (1): 29–38. doi:10.2478/udi-2019-0021. S2CID 210714581.

- ^ Biles, Peter (15 January 2007). "Angola 'made thousands homeless'". BBC News. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ a b Dumba, Dixon; Malpass, Peter. "THE DEVELOPMENT OF LOW INCOME URBAN HOUSING MARKETS: A CASE STUDY OF THE REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA". Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- ^ van Nostrand, John. Old Naledi: The Village Becomes a Town: An Outline of the Old Naledi Squatter Upgrading Project, Gaborone, Botswana. James Lorimer & Company. ISBN 978-0-88862-650-9.

- ^ Bessel, Megan; Guenther, Mathias; Hitchcock, Robert; Lee, Richard; MacGeorge, Gean (January 1989). "Hunters, Clients and Squatters: The Contemporary Socioeconomic Status of Btswana Basarwa". African Study Monographs. 9 (3): 109–151. doi:10.14989/68042.

- ^ Amirah, Ben C. (2001). "Slums As Expressions of Social Exclusion: Explaining The Prevalence of Slums in African Countries" (PDF). United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT). Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ a b "Burkina Faso". MIT. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ a b Bazame, Rodrigue; Tanrivermis., Harun. "Urban Development and Its Implications for Housing Policy: The Case Study of Burkina Faso". European Real Estate Society. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ "Burkina Faso: Developing infrastructure and an enabling environment for sustained access to water and sanitation services for the urban poor". World Bank. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ Soura, Abdramane Bassiahi; Mberu, Blessing; Elungata, Patricia; Lankoande, Bruno; Millogo, Roch; Beguy, Donatien; Compaore, Yacouba (February 2015). "Understanding Inequities in Child Vaccination Rates among the Urban Poor: Evidence from Nairobi and Ouagadougou Health and Demographic Surveillance Systems". Journal of Urban Health. 92 (1): 39–54. doi:10.1007/s11524-014-9908-1.

- ^ Leisz, Stephen (1998). "Burundi Country Profile". In Bruce, John W. (ed.). Country Profiles of Land Tenure: 1996 (PDF). pp. 149–154.

- ^ Fahner, Johannes Hendrik; Happold, Matthew (2019). "THE HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENCE IN INTERNATIONAL INVESTMENT ARBITRATION: EXPLORING THE LIMITS OF SYSTEMIC INTEGRATION". International and Comparative Law Quarterly. 68 (3): 741–759. doi:10.1017/S0020589319000241.

- ^ "An indigenous community in Burundi battles for equal treatment". UNHCR. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for (1 July 2010). "State of the World's Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2010 - Burundi". Refworld. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Kenfack, Pierre-Etienne; Nguiffo, Samuel; Nkuintchua, Téodyl (2016). Land investments, accountability and the law: Lessons from Cameroon. London: International Institute for Environment and Development. ISBN 978-1-78431-341-8.

- ^ Nuesiri, Emmanuel O. (October 2015). "Monetary and non-monetary benefits from the Bimbia-Bonadikombo community forest, Cameroon: policy implications relevant for carbon emissions reduction programmes". Community Development Journal. 50 (4): 661–676. doi:10.1093/cdj/bsu061.

- ^ "Flood-hit Cameroon to demolish low-lying urban homes". news.trust.org. Thomson Reuters Foundation. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Staff writer (18 October 2019). "Cameroonian gov't working on infrastructure plan to eradicate slums - Xinhua | English.news.cn". Xinhuanet. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Côte d'Ivoire - Settlement patterns". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ Bado, Arsene Brice; Boone, Catherine; Dion, Aristide Mah; Irigo, Zibo (27 September 2019). "Regional dynamics of land certification in Côte d'Ivoire". Africa at LSE. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ Aboa, Ange (25 May 2018). "Ivory Coast needs over $1 billion for reforestation strategy". Reuters. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ Van Bockstael, Steven (February 2019). "Land grabbing "from below"? Illicit artisanal gold mining and access to land in post-conflict Côte d'Ivoire". Land Use Policy. 81: 904–914. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.04.045.

- ^ "Coronavirus Côte d'Ivoire : Les squatters du Chu de Cocody crient au secours". Afrik Soir. 5 April 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ Sims, David (2010). Understanding Cairo: The logic of a city out of control. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 9789774164040.

- ^ Hardoy, Jorge Enrique; Satterthwaite, David (1989). Squatter citizen: Life in the urban third world. London: Earthscan. ISBN 9781853830204.

- ^ a b Weldegiorgis, Habtemicael (2009). "The Cadastral System in Eritrea: Practice, Constraints and Prospects". International Federation of Surveyors.

- ^ a b Weldegiorgis, Habtemicael (2015). Land Tenure in Eritrea. From the Wisdom of the Ages to the Challenges of the Modern World. Sofia, Bulgaria.

- ^ Nadel, S. F. (1946). "Land Tenure on the Eritrean Plateau". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 16 (1): 1–22. doi:10.2307/1156534. ISSN 0001-9720.

- ^ a b Holleman, J. F. (1962). Experiment in Swaziland: Report of the random sample survey 1960. Durban: University of Natal.

- ^ Mboumba, Anicet (2011). "La difficile mutation du modèle de gouvernement des villes au Gabon : analyse à partir de la gestion des déchets à Libreville". Annales de géographie. 678 (2): 157. doi:10.3917/ag.678.0157.

- ^ "GABON: Disabled Squatters Highlight The Plight Of The Homeless". Inter Press Service. 21 June 1999. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ a b Wellings, Paul (1983). A case of mistaken identity: The squatters of Lesotho. South Africa: University of Natal. ISBN 0-86980-332-8.

- ^ a b Leduka, Clement R. (2001). From Illegality to Legality: Illegal Urban Development and the Transformation of Urban Property Rights in Lesotho. ESF N-AERUS International Workshop on Coping with Informality and Illegality. Leuven, Belgium.

- ^ a b Leduka, Clement R. (2012). Lesotho Urban Land Market Scoping Study. Institute of Southern African Studies.

- ^ Alfaro, Jose F.; Jones, Brieland (2018). "Social and environmental impacts of charcoal production in Liberia: Evidence from the field". Energy for Sustainable Development. 47: 124–132. doi:10.1016/j.esd.2018.09.004.

- ^ Tipple, Graham (2014). Liberia: Housing profile (PDF). Nairobi, Kenya: UN-HABITAT. ISBN 978-92-1-132626-0.

- ^ Williams, Rhodri C. (2011). Durable Solutions and Development-Induced Displacement in Monrovia, Liberia (PDF). Norwegian Refugee Council.

- ^ Minister of Information (3 May 2007). "President Sirleaf Directs Justice Minister to Evict Squatters from Ducor". Archive.org. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Carter, J. Burgess (28 August 2020). "More than 9,000 Burkinabes Illegally Squatting in Grand Gedeh". Daily Observer. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Johnson, Obediah (18 January 2021). "Government of Liberia Launches Processes Leading to Digitization And Systematic Land Titling". Front Page Africa. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Elfarnouk, Nouri A. (2015). SQUATTER SETTLEMENTS IN TRIPOLI, LIBYA: ASSESSING, MONITORING, AND ANALYZING THE INCIDENCE AND PREVALENCE OF URBAN SQUATTER AREAS IN THE PERI-URBAN FRINGE (PhD). University of Kansas.

- ^ Najm, Mahmoud Abdalla (1982). Agricultural Land Use in the Benghazi Area, Libya: A Spatial Analysis of Cultural Factors Affecting [sic] Crop and Livestock Patterns. Michigan State University. Department of Geography. p. 117.

- ^ Staff writer (27 December 2019). "Fighting in Tripoli leaves thousands of Libyans homeless". MEO. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ Loyd, Anthony (17 February 2020). "Anthony Loyd's Libya war diary". The Times. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ Ranjatson, Patrick; McClain, Rebecca; Mananga, Jean; Lawry, Steven; Randrianasolo, Renaud; Razafimbelo, Ny Tolotra (2019). "Tenure Security and Forest Landscape Restoration: Results from Exploratory Research in Boeny, Madagascar" (PDF). Paper prepared for presentation at the “2019 WORLD BANK CONFERENCE ON LAND AND POVERTY”.

- ^ Burnod, Perrine; Gingembre, Mathilde; Andrianirina Ratsialonana, Rivo (March 2013). "Competition over Authority and Access: International Land Deals in Madagascar: International Land Deals in Madagascar". Development and Change. 44 (2): 357–379. doi:10.1111/dech.12015.

- ^ Madagascar Case Study: How Law and Regulation Supports Disaster Risk Reduction (PDF). Geneva: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. 2014.

- ^ Widman, Marit (2014-01-02). "Land Tenure Insecurity and Formalizing Land Rights in Madagascar: A Gender Perspective on the Certification Program". Feminist Economics. 20 (1): 130–154. doi:10.1080/13545701.2013.873136.

- ^ Brautigam, Deborah (2015). Will Africa Feed China?. Oxford University Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-19-939686-3.

- ^ Kanyongolo, Fidelis Edge (2005). "Land occupations in Malawi: Challenging the Neoliberal Legal Order". In Moyo, Sam; Yeros, Paris (eds.). Reclaiming the Land: The Resurgence of Rural Movements in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Zed Books. pp. 118–141. ISBN 978-1-84277-425-0.

- ^ a b Neimark, Benjamin; Toulmin, Camilla; Batterbury, Simon (4 May 2018). "Peri-urban land grabbing? dilemmas of formalising tenure and land acquisitions around the cities of Bamako and Ségou, Mali". Journal of Land Use Science. 13 (3): 319–324. doi:10.1080/1747423X.2018.1499831.

- ^ Mango, Cecily. Mali, a country profile. The Office. p. 19.

- ^ a b Simard, Paule; Koninck, Maria De (July 2001). "Environment, living spaces, and health: Compound-organisation practices in a Bamako squatter settlement, Mali". Gender & Development. 9 (2): 28–39. doi:10.1080/13552070127744.

- ^ Mango, Cecily. Mali, a country profile. The Office. p. 13.

- ^ BTI 2018 Country Report — Mauritania. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung. 2018.

- ^ "ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF MAURITANIA POVERTY REDUCTION STRATEGY PAPER". IMF. 2011.

- ^ a b Choplin, Armelle; Dessie, Elizabeth (June 2017). "Titling the desert: Land formalization and tenure (in)security in Nouakchott (Mauritania)". Habitat International. 64: 49–58. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2017.04.003.

- ^ Vijayalakshmi, Teelock; Satyendra, Peerthum (2017). Transition from Slavery in Zanzibar and Mauritius. CODESRIA. ISBN 978-2-86978-680-6.

- ^ Nwulia, Moses D. E. (1978). "The "Apprenticeship" System in Mauritius: Its Character and Its Impact on Race Relations in the Immediate Post-Emancipation Period, 1839-1879". African Studies Review. 21 (1): 89–101. doi:10.2307/523765. ISSN 0002-0206.

- ^ Modeliar, S. (12 August 2010). "The Issue of Squatters". Mauritius Times. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Evicted squatters will benefit from NHDC assistance, says Minister Obeegadoo". Public Infrastructure. Republic of Mauritius. 3 June 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ Staff writer (24 August 2021). "Pointe-aux-Sable squatters: Four families are still waiting for housing". Mauritius News. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ Weissman, Juliana (1977). Kingdom of Morocco. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. p. 18.

- ^ Nelson, Harold D. Morocco, a Country Study. Headquarters, Department of the Army. p. 108.

- ^ a b Arandel, Christian; Wetterberg, Anna (February 2013). "Between "Authoritarian" and "Empowered" slum relocation: Social mediation in the case of Ennakhil, Morocco". Cities. 30: 140–148. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2012.02.005.

- ^ Staff writer (25 October 2018). "African migrants in Morocco adamant to cross to Europe". Middle East Online. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ Myers, Gregory W. (December 1994). "Competitive rights, competitive claims: land access in post‐war Mozambique". Journal of Southern African Studies. 20 (4): 603–632. doi:10.1080/03057079408708424.

- ^ Hughes, David McDermott (1999). "Refugees and Squatters: Immigration and the Politics of Territory on the Zimbabwe-Mozambique Border". Journal of Southern African Studies. 25 (4): 533–552. ISSN 0305-7070.

- ^ Hammar, Amanda (June 2010). "Ambivalent Mobilities: Zimbabwean Commercial Farmers in Mozambique". Journal of Southern African Studies. 36 (2): 395–416. doi:10.1080/03057070.2010.485791.

- ^ "In pictures: The squatters of Mozambique's Grande Hotel". BBC News. 21 April 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ "Hôtes de la nuit (Les) Hóspedes da Noite". Africultures (in French). Africultures. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Ebekozien, Andrew; Abdul-Aziz, Abdul-Rashid; Jaafar, Mastura (9 April 2019). "Low-cost housing policies and squatters struggles in Nigeria: the Nigerian perspective on possible solutions". International Journal of Construction Management: 1–11. doi:10.1080/15623599.2019.1602586.

- ^ Nwannekanma, Bertram (13 July 2020). "Coronavirus fuelling increase in homelessness, squatters, say experts". Guardian. Nigeria. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "United Nations Population Division". United Nations. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ Ogunlesi, Tolu; Esiebo, Andrew (23 February 2016). "Inside Makoko: Danger and ingenuity in the world's biggest floating slum". The Guardian. England. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ Wallace, David A.; Pasick, Patricia; Berman, Zoe; Weber, Ella (October 2014). "Stories for Hope–Rwanda: A psychological–archival collaboration to promote healing and cultural continuity through intergenerational dialogue". Archival Science. 14 (3–4): 275–306. doi:10.1007/s10502-014-9232-2.

- ^ Cullen, Paul (28 November 1996). "Squatters watch and wait as refugees head for home". The Irish Times. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ^ a b Álvarez de Andrés, Eva; Cabrera, Cecilia; Smith, Harry (April 2019). "Resistance as resilience: A comparative analysis of state-community conflicts around self-built housing in Spain, Senegal and Argentina". Habitat International. 86: 116–125. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2019.03.003.

- ^ a b Durand-Lasserve, Alain; Ndiaye, Selle (2008). The social and economic impact of land titling programmes in Dakar, Senegal. Government of Norway.

- ^ Wilson, Sigismond A. (1 March 2013). "Company–Community Conflicts Over Diamond Resources in Kono District, Sierra Leone". Society & Natural Resources. 26 (3): 254–269. doi:10.1080/08941920.2012.684849.

- ^ "Land tenure, food security and investment in postwar Sierra Leone" (PDF). FAO. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ Njoh, Ambe J.; Akiwumi, Fenda. "Colonial legacies, land policies and the millennium development goals: Lessons from Cameroon and Sierra Leone". Habitat International. 36 (2): 210–218. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2011.08.002.

- ^ Dumbaya, Peter A. (28 June 2013). "Police versus Squatters: Dilemmas of Land Tenure in Sierra Leone". The Patriotic Vanguard. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ a b Bakonyi, Jutta; Chonka, Peter; Stuvøy, Kirsti (August 2019). "War and city-making in Somalia: Property, power and disposable lives". Political Geography. 73: 82–91. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.05.009.

- ^ "Somalia moves to evict Mogadishu squatters". BBC News. 6 February 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ Hujale, Moulid (27 January 2020). "Mogadishu left reeling as conflict and climate shocks spark rush to capital". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ Youé, Christopher (2002). "Black Squatters on White Farms: Segregation and Agrarian Change in Kenya, South Africa, and Rhodesia, 1902–1963". The International History Review. 24 (3): 558–602. doi:10.1080/07075332.2002.9640974.

- ^ Kono, Sayaka (2014). "Being Inclusive to Survive in an Ethnic Conflict: The Meaning of 'Basotho' for Illegal Squatters in Thaba Nchu, 1970s" (PDF). Southern African Peace and Security Studies. 3 (1): 27–43.

- ^ McMichael, Gabriella (2014). "Rethinking access to land and violence in post-war cities: reflections from Juba, Southern Sudan". Environment and Urbanization. 26 (2): 389–400. doi:10.1177/0956247814539431.

- ^ a b Gamie, Sumaia Omer Moh. "Tackling Squatter Settlements in Sudanese Cities (SSISC)" (PDF). High Level Symposium on Sustainable Cities. United Nations. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ a b c Stren, Richard E. (January 1982). "Underdevelopment, Urban Squatting, and The State Bureaucracy: A Case Study of Tanzania". Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue canadienne des études africaines. 16 (1): 67–91. doi:10.1080/00083968.1982.10803994.

- ^ Stren, Richard. Urban Squatting in Tanzania with Special Reference to Sar es Salaam. World Bank.

- ^ Ferjani, M.C. (1986). "La réhabilitation d'un gourbiville: Saïda-Mannoubia à Tunis". In Haeringer, Philippe; Ganne, B. (eds.). Anthropologie et sociologie de l'espace urbain (in French). Université de Lyon 2.GLYSI. pp. 125–136.

- ^ a b "Tunisia Housing Profile" (PDF). UN-HABITAT. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ Hall, Bogumila (2017). ""This is our homeland": Yemen's marginalized and the quest for rights and recognition". Chroniques yéménites (9). doi:10.4000/cy.3427.

- ^ Mpofu, Busani (14 September 2012). "Perpetual 'Outcasts'? Squatters in peri-urban Bulawayo, Zimbabwe". Afrika Focus. 25 (2). doi:10.21825/af.v25i2.4946.

- ^ Matabvu, Debra; Agere, Harmony (11 January 2015). "Squatters: Housing shortages or lawlessness?". The Sunday Mail. Archived from the original on 8 November 2018. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "Zimbabwe: Mugabe's clean-up victims flock back to squatter camps – Zimbabwe". Zim Online. 21 September 2005. Archived from the original on 17 March 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.