Wikipedia:Reference desk/Archives/Science/2014 June 11

| Science desk | ||

|---|---|---|

| < June 10 | << May | June | Jul >> | June 12 > |

| Welcome to the Wikipedia Science Reference Desk Archives |

|---|

| The page you are currently viewing is an archive page. While you can leave answers for any questions shown below, please ask new questions on one of the current reference desk pages. |

June 11

How does pentobarbital cause death?

Chemically, what is the mechanism by which pentobarbital causes respiratory arrest? 203.45.159.248 (talk) 08:00, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- This search should give you the answers you seek.--William Thweatt TalkContribs 08:17, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- In general you're looking at a depressant causing respiratory depression. In specific there are drugs like bemegride that can oppose respiratory arrest from the drug - I don't know if BIMU-8 works on it; I didn't see anything about 5-HT4 receptor on PubMed, but did turn up an old paper about 5-HT2 receptor. [1] I'm sorry, but I'd really have to search longer than I want to right now to get a more compelling answer, but a key concept seems to be inspiratory discharge. Wnt (talk) 18:15, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

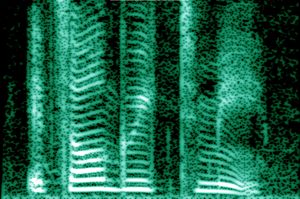

Energy distribution in speech

Is there freely available data on the distribution on energy in speech? I'm interested in the energy distribution averaged over many speakers. I want to know what frequency range would contain X% of the energy in speech, for different values of X. (To make the question more precise, we can add the condition that the fractions of energy above and below the frequency range are the same.) I'm also curious as to whether the energy distribution in speech varies significantly among languages. Thanks. --173.49.79.84 (talk) 10:51, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- The voiced speech of a typical adult male has a fundamental frequency from 85 to 180 Hz, and that of a typical adult female from 165 to 255 Hz. However for intelligibility we need to produce and hear higher voice frequencies and for telephony the usable voice frequency band ranges from approximately 300 Hz to 3400 Hz. We can hear a much wider range of frequencies which are documented by the Fletcher–Munson curves that are averaged over many listeners and indicate outer limits at 20 Hz and 20 000 Hz. Within this range we find various voice types:

- The cry of a baby seems to correlate with the most sensitive part of the Fletcher–Munson curves, an obvious evolutionary advantage for the baby

- When adults sing their voices may be categorized as Bass - Baritone - Tenor - Countertenor - Contralto - Mezzo-soprano - Soprano but there is no authoritative system of Voice classification in non-classical music. 84.209.89.214 (talk) 12:35, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- I believe it takes more energy to produce the same subjective volume at a lower frequency. Hence, most of the energy in speech will be spent on those lower frequencies. However, note that the amount of energy used to talk is very low, no matter what the frequencies. StuRat (talk) 16:24, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- Crandall and MacKenzie, "Analysis of the energy distribution in speech", Bell System Technical Journal, 1922

- Crandall is the pioneer of of this kind of analysis. I don't know how accurate his work is considered nowadays (no reason to believe it isn't) but it meets your requirement of being freely available. SpinningSpark 07:53, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

Black solid

Hypothetically, would it be possible to create a crystal, composed of transient microblackholes? Plasmic Physics (talk) 12:49, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- Hypothetically yes, because one need only invoke the conjecture that such a crystal is possible to declare "then let it be". But in the known world a Crystal consists of an ordered pattern of atoms that is stable because of van der Waals forces (the sum of the attractive or repulsive forces between molecules) in equilibrium. So all you need is a hypothesis about both attractive and repulsive forces existing between as yet hypothetical Micro black holes, and your crystal recipe is good to go. 84.209.89.214 (talk) 13:20, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- OK. I know that such a crystal would require a different type of force holding it together. I have heard of a type of technique, where lasers control the position of (charged?) objects, demonstrated on micro-sized polystyrene beads. Plasmic Physics (talk) 13:40, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- By this standard you could call the pattern of tiles in a suspended ceiling a crystal. Now to be sure, the nature of the smallest possible black hole or 'black hole remnant' is unknown, sometimes people try to connect them with particles or suggest some quantum theory basis exists, but unless and until you can explain the forces that would lead them to spontaneously form a stable array in space, it's not really useful to speak of a crystal. Wnt (talk) 16:11, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- (ec) I think it would more be along the lines of what would hold it apart (keep it from collapsing). Laser light would most likely be severely attenuated by an array of micro-black holes, and would normally be expected to be highly unstable in the sense of crystalline structure – imagine a little swarm of gravitationally bound micro-black holes. There is a not insignificant net attractive force, which would have to be balanced. One could imagine them all carrying the same charge (Reissner–Nordström black holes) that results in mutual repulsion almost exactly balancing their gravitational attraction, possibly exceeding it – but I suspect these might be super-extremal. Your suggestion of transient micro-black holes suggests immense quantities of energy while they evaporate and presumably reform – not something that one would normally call a crystal, other than possibly a space-time crystal. —Quondum 16:25, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- OK. I know that such a crystal would require a different type of force holding it together. I have heard of a type of technique, where lasers control the position of (charged?) objects, demonstrated on micro-sized polystyrene beads. Plasmic Physics (talk) 13:40, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- I've just noticed the article Holeum. I haven't had time to read it, but it seems to relate. —Quondum 22:11, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- Thank for the link, very interesting response above as well. Plasmic Physics (talk) 23:26, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- I'm pretty sure that article is pseudoscience and should be deleted. -- BenRG (talk) 07:48, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- @BenRG: I can see why 'actaphysica.com' doesn't inspire confidence that it is a WP:RS. However, the principle work seems to have appeared in the journal Classical and Quantum Gravity, here [2]. Now, I can't scientifically review the article, but C&QG seems like a fairly legit journal to me. My point is, published critiques could be added to the article, but IMHO being published in a reputable journal is usually not a sign of pseudoscience. Not that that means bad stuff doesn't get through sometimes... SemanticMantis (talk) 14:07, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- Well, my suspicion is that the paper, linked web pages, and Wikipedia article are all the work of one person. The argument that two black holes should orbit at an integral (or is it an odd because graviton has spin 2?) multiple of the Planck constant in angular momentum makes sense enough, but the author makes some strange references to structure within a black hole when they rotate within an event horizon... how do you describe quantum numbers of stable orbits in the regime where no stable orbit exists, which is true even around neutron stars with photon shells? I really ought to do the math before speaking about something I'm so ignorant of, but I'm feeling skeptical the black holes can be small enough or come close enough together without simply merging for the Planck constant to become relevant. Can someone walk us through that? Wnt (talk) 15:43, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- From an outside perspective (meaning that I am not qualified to interpret the detail), this does sound as though it contradicts GR. This is, however, known to be inaccurate in some sense in this context, and semi-speculative investigations of this nature should be encouraged, without them being labelled as pseudoscience. It may merit publication. However, this appears to be a single primary source, and almost certainly does not seem to me to satisfy the notability requirements of WP. As such, I'm not convinced that the article should be in WP, notwithstanding its disclaimer ("hypothetical"). It would be nice if someone could do as Wnt asks: give enough context to help us understand the merit of the concept. —Quondum 16:51, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- On the 'single primary source' -- at least 15 other works have cited it [3], and many also mention the Holeum concept. Yes, some of those are from the same author, and yes, some are only ArXiv preprints, but ~10 are articles in real peer-reviewed journals that don't share any authorship with the original. My only contention is that this does not seem to be a clear example of pseudoscience. At worst, it might be wrong science or poor science, but we have WP articles on all kinds of topics like that ;) SemanticMantis (talk) 17:24, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- From an outside perspective (meaning that I am not qualified to interpret the detail), this does sound as though it contradicts GR. This is, however, known to be inaccurate in some sense in this context, and semi-speculative investigations of this nature should be encouraged, without them being labelled as pseudoscience. It may merit publication. However, this appears to be a single primary source, and almost certainly does not seem to me to satisfy the notability requirements of WP. As such, I'm not convinced that the article should be in WP, notwithstanding its disclaimer ("hypothetical"). It would be nice if someone could do as Wnt asks: give enough context to help us understand the merit of the concept. —Quondum 16:51, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- The original preprint is ridiculous. Even if you don't know any of the physics you should be able to tell that something is wrong. There is apparently no general relativity in this document. They just assume a 1/r² Newtonian force and the Schrödinger equation, so of course they get hydrogen atom solutions. They don't seem to be aware that bound states of black holes are unstable to mergers. They do seem to be aware of Hawking radiation, since they mention it in the intro as an objection to the idea of stable holeum, and argue that it would be irrelevant in the early universe. Later they propose stable holeum as a dark matter candidate. So apparently they think that once the holeum forms in the early universe, the stability problem is solved forever, or something. I don't know. Also, apparently we haven't seen cosmological domain walls because they're made of "haloes of the holeums" (section IV). I guess the holeums produce fake starlight and cosmic microwave background radiation too. I don't know what the published paper looked like (I would have to pay to see it), but I think that anyone capable of writing that preprint is incapable of producing a journal article of any value.

- As for other people citing these guys... read the articles instead of counting them. Rabinowitz is another Microsoft Word aficionado who publishes in vanity journals. The Khlopov article begins "The convergence of the frontiers of our knowledge in micro- and macro- worlds leads to the wrong circle of problems, illustrated by the mystical Uhroboros". And then it never says anything about "holeum", just primordial black holes, so it doesn't support the sentence for which it is used as a reference in the Wikipedia article. It was obviously included because it's one of the few citations the Chavdas have, but there's no sign that Khlopov read their article or many of the 285 others that he cites. I can't find Al Dallal's articles on the arXiv (already a bad sign), but I think that "Advances in Space Research" is not a top-tier journal. -- BenRG (talk) 20:21, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- AfD (SemanticMantis's comments notwithstanding)? An article of this nature needs to be written in a commentator tone, which is not really possible without a secondary source. I've seen a new, obviously good science article with a few secondary sources go to AfD, still to receive a "marginally notable" comment. Just because other articles haven't been axed is not an argument – the article must at least be able to present the topic in a balanced fashion, and it is difficult to do so in this case. —Quondum 14:14, 13 June 2014 (UTC)

- After reading these comments and looking through more of the papers, I'm convinced it's at least a decent candidate for deletion. I'll keep an eye there for a few days to see if anyone wants to post it. SemanticMantis (talk) 15:24, 13 June 2014 (UTC)

- I am so not fond of deletion ... the problem is, at some point somebody sees "holeum" mentioned on a forum somewhere (maybe here) and just wants to find out what the hell it is. This is better done by explaining how little there is about the topic in the literature than by blunting our coverage of what is there, even if it is bunk. Wnt (talk) 18:41, 13 June 2014 (UTC)

- After reading these comments and looking through more of the papers, I'm convinced it's at least a decent candidate for deletion. I'll keep an eye there for a few days to see if anyone wants to post it. SemanticMantis (talk) 15:24, 13 June 2014 (UTC)

- AfD (SemanticMantis's comments notwithstanding)? An article of this nature needs to be written in a commentator tone, which is not really possible without a secondary source. I've seen a new, obviously good science article with a few secondary sources go to AfD, still to receive a "marginally notable" comment. Just because other articles haven't been axed is not an argument – the article must at least be able to present the topic in a balanced fashion, and it is difficult to do so in this case. —Quondum 14:14, 13 June 2014 (UTC)

- Well, my suspicion is that the paper, linked web pages, and Wikipedia article are all the work of one person. The argument that two black holes should orbit at an integral (or is it an odd because graviton has spin 2?) multiple of the Planck constant in angular momentum makes sense enough, but the author makes some strange references to structure within a black hole when they rotate within an event horizon... how do you describe quantum numbers of stable orbits in the regime where no stable orbit exists, which is true even around neutron stars with photon shells? I really ought to do the math before speaking about something I'm so ignorant of, but I'm feeling skeptical the black holes can be small enough or come close enough together without simply merging for the Planck constant to become relevant. Can someone walk us through that? Wnt (talk) 15:43, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- @BenRG: I can see why 'actaphysica.com' doesn't inspire confidence that it is a WP:RS. However, the principle work seems to have appeared in the journal Classical and Quantum Gravity, here [2]. Now, I can't scientifically review the article, but C&QG seems like a fairly legit journal to me. My point is, published critiques could be added to the article, but IMHO being published in a reputable journal is usually not a sign of pseudoscience. Not that that means bad stuff doesn't get through sometimes... SemanticMantis (talk) 14:07, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- I'm pretty sure that article is pseudoscience and should be deleted. -- BenRG (talk) 07:48, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

Why aren't dolphins and killer whales considered whales?

Whales are one of relatively few mammals living in the sea, and it was once a land-creature, or at least amphibious. Not the whale itself, obviously, but its ancestors. Evolution has seen it develop into a whale and fully marine. Science have more or less proven this, and they speculate that this is why all whales swim differently than fish. Instead of sideways movements with tail and body, the whale makes up-and-down movements, like a mermaid. Just look at any clip/video of fish and whales.

The Dolphin and Killer Whale also swim with up-and-down movements and they also descend from the same amphibious creatures as the whale. They are all 'Cetaceans'. The name Killer Whale is misleading, because it isn't actually a whale. It is a 'killer of whales', that's where the name stem from, given by Spanish traders/sailors in the 1700 or something like that... The Killer whale is actually a giant dolphin.

But why is it that dolphins and especially Killer Whales are not considered whales? What makes them different? I have seen it suggested that it might be something so small as the teeth, that those who have teeth are not considered whales. But Sperm whale is certainly considered a whale, and this one has teeth. The difference can't be that small, or so I would think at least.

Krikkert7 (talk) 13:01, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- According to our article Toothed whale, orcas, dolphins and porpoises are considered to be a type of whale. If you're asking why they're not called whales, then that's just how the English language developed. Given the enormous difference in size of these creatures, it's not surprising that ancient fishermen came up with a different word to describe the biggest ones. Rojomoke (talk) 14:04, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- That's right. The article on Artiofabula has a cladogram that explains the relations between cetaceans (baleen whales, toothed whales, dolphins, porpoises, river dophins, beaked whales, narwhal, etc.) and their closest relatives, living and extinct. The order Cetacea is monophyletic; all cetaceans share a common evolutionary ancestor. Regarding the origin of the word "whale" in English: counterintuitively, it seems (according to Merriam-Webster) to be derived from Latin squalus - sea fish :). Less confusingly, the Latin cetus or Russian kit for whale both derived from Greek keto meaning a huge sea-monster. In modern Hebrew, too, a word for a whale is leviathan (pronounced lev`yatan) - originally a sea-monster. Dr Dima (talk) 17:25, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- wikt:Fish has a great quote from 1774: "The whale, the limpet, the tortoise and the oyster… as men have been willing to give them all the name of fishes, it is wisest for us to conform." It should be clear that the redefinition of fish as a clade rather than a habit is a recent phenomenon. Wnt (talk) 18:02, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- As noted above, dolphins are not always referred to as whales, but that is a matter of how English is used. They are zoologically considered to be whales, that is, Cetacea. The issue in terms of English usage isn't teeth but size. The sperm whale, as noted, is always referred to as a whale, and it is a large toothed whale. The orca, larger than the dolphins and smaller than the sperm whale, is also known as the killer whale, which implies that it has always been considered a whale. As to 1774, that is approximately the same time as Linnaeus published Systema Naturae, and he separated the whales from the fishes. The concept of clades is of twentieth-century origin, but Linnaeus defined a class (rank-based taxon) of fish, a class of mammals, a class of reptiles, and other classes. (The phylum is a more recent higher-level taxon, and subsequently fish were split into three classes.) Robert McClenon (talk) 19:36, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- English is a funny language. Ladybirds aren't birds (even self-evidently so!), shellfish aren't fish, you can't saddle a seahorse, etc. Dolphins and orcas are whales, however, even if the word "whale" doesn't appear in their name. However, this is certainly no different than tigers and lions being felines even though the word "cat" doesn't appear in their names. --Jayron32 20:02, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- That's why I use "ladybug". Still technically not a bug, but getting closer. "Ladybird" to me is a former human or fake dog. We have tiger cats in Hamilton. And as for saddling a seahorse... InedibleHulk (talk) 19:40, 14 June 2014 (UTC)

- English is a funny language. Ladybirds aren't birds (even self-evidently so!), shellfish aren't fish, you can't saddle a seahorse, etc. Dolphins and orcas are whales, however, even if the word "whale" doesn't appear in their name. However, this is certainly no different than tigers and lions being felines even though the word "cat" doesn't appear in their names. --Jayron32 20:02, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- Languages in general have funny aspects to them, as to the people who use them. Robert McClenon (talk) 20:14, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- It's not at all a linguistic foible. The 1792 edition of Johnson's dictionary defines a fish as "an animal that inhabits the water". There's no qualification about scales or backbones or laying eggs. The current OED is the same, saying "in popular language, any animal living exclusively in the water". Collins American English Dictionary is similar, saying "any animal living in water only, as a dolphin, crab, or oyster". What's changed over two centuries is better scientific understanding of the classification of marine animals and the realisation that marine invertebrates are very dissimilar from trout, which are themselves unlike dolphins. This (somewhat) more scientific definition of "fish", which confines it to the scaly vertebrates described in the fish article, has entered the language, and is now the more common use - OED notes "popular usage now tends to approximate [the scientific usage]". Scientific usages get to guide what words mean, but not force change when those words don't neatly confirm to nature. In ordinary writing, it's surely obtuse, and somewhat archaic, to call a jellyfish or a whale or a starfish a "fish"; but it's not wrong to do so. In scientific writing it would be wrong, but marine biologists mostly use more precise terms anyway and don't say "fish" except at cocktail parties (and who invites some beardie who smells of scaly marine vertebrates to their cocktail party anyway). This is just the same for the cetaceans, where ancient common names which precede all of science don't match a later taxonomy. So it is with whether Pluto is a "planet", and whether a mushroom is a "plant". -- Finlay McWalterᚠTalk 21:28, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- Linnaeus probably never read Johnson's dictionary in the original, because he was Swedish and wrote in Latin, and was dead by 1792, and Johnson had probably never read Systema Naturae, but Linnaeus had begun the process of using more precise terminology at the same time as Johnson had been formalizing the less precise terminology. Robert McClenon (talk) 15:46, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- Well, scientists can't force natural language, but they can force scientific vocabulary in the academic domain. This also related to the notion of common names and scientific names. When we try to use common names in a more rigorous fashion, we end up with things like true bug and true fish. Despite conjuring up an image of no true Scotsman, these terms are fairly well defined. (p.s. some of the best cocktail parties I've ever been to have been hosted by a marine biologist. They usually wash beforehand ;) SemanticMantis (talk) 13:54, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- It's not at all a linguistic foible. The 1792 edition of Johnson's dictionary defines a fish as "an animal that inhabits the water". There's no qualification about scales or backbones or laying eggs. The current OED is the same, saying "in popular language, any animal living exclusively in the water". Collins American English Dictionary is similar, saying "any animal living in water only, as a dolphin, crab, or oyster". What's changed over two centuries is better scientific understanding of the classification of marine animals and the realisation that marine invertebrates are very dissimilar from trout, which are themselves unlike dolphins. This (somewhat) more scientific definition of "fish", which confines it to the scaly vertebrates described in the fish article, has entered the language, and is now the more common use - OED notes "popular usage now tends to approximate [the scientific usage]". Scientific usages get to guide what words mean, but not force change when those words don't neatly confirm to nature. In ordinary writing, it's surely obtuse, and somewhat archaic, to call a jellyfish or a whale or a starfish a "fish"; but it's not wrong to do so. In scientific writing it would be wrong, but marine biologists mostly use more precise terms anyway and don't say "fish" except at cocktail parties (and who invites some beardie who smells of scaly marine vertebrates to their cocktail party anyway). This is just the same for the cetaceans, where ancient common names which precede all of science don't match a later taxonomy. So it is with whether Pluto is a "planet", and whether a mushroom is a "plant". -- Finlay McWalterᚠTalk 21:28, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- True fish is ambiguous. Is it limited to bony fish, as it was piped above, or does it include cartilage fish? Many people who understand that whales are not fish would refer to sharks as fish. That is why scientists prefer to use scientific names, which are unambiguous unless there are disputes as to classification. Robert McClenon (talk) 21:58, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- When I took our new puppy to the vet to get his shots, he asked: "Do you have any other animals in your house?" - to which, I might reply. "Just, my Wife."...which generally elicits a laugh - but why? Humans are animals too. Most people don't understand that formally, spiders aren't insects - that mushrooms aren't plants - that dolphins aren't fish - that the sun is a star - that birds are dinosaurs and that beans, corn, wheat and tomatoes are all fruit.

- Yes. "Apes don't talk." "One species of ape can talk." Robert McClenon (talk) 21:56, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- Whether birds are dinosaurs is a matter of terminology. Birds belong to the clade to which dinosaurs belonged, and are the only surviving member of the clade. However, using rank-based taxonomy, many modern zoologists define dinosaurs as Archosauria, and retain the Linnaean definition of birds as Aves. Robert McClenon (talk) 21:56, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- There is a distinct difference between normal language, used informally by the vast majority of people - and scientific language, ideally used in a specific manner, with great precision. Even scientist are very often fuzzy in their use of it. If I ask "When exactly did the dinosaurs go extinct?" most will say "66 million years ago" - and not "Eh? What do you mean? They didn't go extinct. I keep one as a pet."

- Same deal here. Technically, dolphins are most definitely whales...informally, it's useful to distinguish them from those really, really big fish that we call "whales".

- That is, to distinguish them from those really, really big non-fish fish that we call whales. Robert McClenon (talk) 21:58, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- In truth, it's even harder than that. Scientists do try to apply formal definitions to words - but very often the required precision evades them. The definition of "planet" was nicely vague - and the effort to formally define it in a way that didn't require rewriting every planetary science text book was enormously difficult and controversial - and in the end really shoudl require every one of those textbooks to be rewritten. Other words that we thought had meaning, like "species" (meaning: a group of living things that can interbreed with each other - but not with other living things) turns out to be generally useful - but doesn't stand up to really close scrutiny because there are too many animals and plants that bend that definition to breaking point. Even words you might think have precision such as "temperature" seem to break down in the near-vacuum of space. Words like "simultaneous" that Einstein made essentially meaningless are still to be found in all sorts of very formal scientific papers because they are sufficiently meaningful most of the time.

- In the end, it's just important to understand what really "is" - and not stress out too much about the language we use to describe that understanding. So we can go on telling our vet that the only other animal in our house is our cat - because in the context he asked, we knew what he needed to know and language is sufficiently flexible to allow us to be that vague.

- SteveBaker (talk) 17:34, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

Thanks guys for all the response :) Krikkert7 (talk) 19:32, 14 June 2014 (UTC)

Avalanche transistor stack triggering

Why do most researchers and scientists seem to use 'base triggering' of the bottom device in the stack when it is well known that this technique creates triggering uncertainty and jitter? Why dont people use collector triggering? It cant be that hard, can it? The article Avalanche transistor says that collector triggering is impractical if a diode is used because of the reverse voltage rating needed. But I am sure there must be another way to inject a voltage pulse from a low voltage trigger circuit at the collector of the bottom transistor in a stack even though it may be elevated by 100v or so. What about capacitive coupling-- or am I missing something fundamental here?--86.176.20.195 (talk) 15:07, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- The article Avalanche transistor states that a collector triggering circuit "requires a diode capable of resist[ing...] high reverse voltages and switch[ing] very fast, characteristics that are very difficult to realize in the same diode, therefore it is rarely seen in modern avalanche transistor circuits." Is your stack connection of transistors like this cascode circuit? Base drive requires only low current because of the current gain hfe of the driven transistor and a small voltage swing. The fastest possible switching is obtained when there are no triggering components that add capacity at the collector output, and there is minimum feedback of the output to the input. 84.209.89.214 (talk) 22:22, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

Why no huge fires on Titan?

If Titan is full of hydrocarbon, and I assume not immune from asteroids, meteorites, or whatever hits from space, then why don't such collisions produce giant fires that burn up the hydrocarbon lakes and whatnot? 24.215.188.243 (talk) 17:24, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- Think about it. Why does a grease fire on the oven go out when you put a lid on it? Fire is ultimately a redox reaction, requiring a reducing agent and an oxidizing agent. Here on Earth we have lots of oxygen in the atmosphere, so "fuel" to us includes hydrocarbons. But on Titan there are plenty of those, and it would be things like liquid oxygen that would you would use as fuels there. You're right about one thing: if the atmosphere could burn, it very probably would have long ago (indeed even as the moon was first forming it) Wnt (talk) 17:34, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- To simplify, hydrocarbons on Titan do not burn because there is no oxygen to oxidize the hydrocarbons. We have fires on Earth because we have organic material and oxygen. There would have been no fires on Earth until about 2.5 billion years ago, when the cyanobacteria began photosynthesizing. Oxygen in combination with organic material is an unstable mixture, because fires happen on Earth. The only reason why there continues to be oxygen is that trees (and other plants) continue producing it. Robert McClenon (talk) 19:43, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- Even more importantly, we ONLY have free oxygen on Earth because we have life. The existence of high concentrations of free oxygen is one of the signs that life may exist on a planet. AFAIK, we're the only planet we've ever found with that has such concentrations of free oxygen, because without all of the plants breathing it out into the atmosphere, it'd all get used up burning everything, until it was essentially all gone. --Jayron32 19:59, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- Jayron32 and I are saying the same thing. Robert McClenon (talk) 20:13, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- Yes, we do appear to be. --Jayron32 20:21, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- Also, you agree with each other. —Tamfang (talk) 03:22, 13 June 2014 (UTC)

- And you agree with both of them as to the state of their agreement. --Trovatore (talk) 03:26, 13 June 2014 (UTC)

- I saw a video once that blew my mind a little, it was of a glass tank full of gas, with a tube in it leading from a bottle of oxygen. The oxygen was turned on and the end of the tube was ignited, it looked exactly like a flame of gas burning in a tank of air. Vespine (talk) 04:00, 13 June 2014 (UTC)

- And you agree with both of them as to the state of their agreement. --Trovatore (talk) 03:26, 13 June 2014 (UTC)

- Also, you agree with each other. —Tamfang (talk) 03:22, 13 June 2014 (UTC)

- Yes, we do appear to be. --Jayron32 20:21, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- Jayron32 and I are saying the same thing. Robert McClenon (talk) 20:13, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- Even more importantly, we ONLY have free oxygen on Earth because we have life. The existence of high concentrations of free oxygen is one of the signs that life may exist on a planet. AFAIK, we're the only planet we've ever found with that has such concentrations of free oxygen, because without all of the plants breathing it out into the atmosphere, it'd all get used up burning everything, until it was essentially all gone. --Jayron32 19:59, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- To simplify, hydrocarbons on Titan do not burn because there is no oxygen to oxidize the hydrocarbons. We have fires on Earth because we have organic material and oxygen. There would have been no fires on Earth until about 2.5 billion years ago, when the cyanobacteria began photosynthesizing. Oxygen in combination with organic material is an unstable mixture, because fires happen on Earth. The only reason why there continues to be oxygen is that trees (and other plants) continue producing it. Robert McClenon (talk) 19:43, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- See The Dust of Death for a fictional application of this lesson. —Tamfang (talk) 04:18, 15 January 2020 (UTC)

perceptual motion

Since we all know perceptual motion is against the laws of physics, please explain what is happening here http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oJv58SXx2V8 — Preceding unsigned comment added by 186.88.84.72 (talk) 17:25, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- Even a nice pendulum will swing for a very long time, but we don't consider that perpetual motion, do we? This oscillator is just a fancy pendulum, it will succumb to friction eventually. SemanticMantis (talk) 17:31, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- No, this is a better trick than that. The level of workmanship shown there is quite excellent, there is no really obvious video fakery, and the device does actually seem to speed up during the first few revolutions. Nonetheless, this is still by all expectation simply a good magic trick. My suspicion is that the somewhat oversized black casing holding the dowel is what contains the magic. As we see in the first half, the magnet wheel can indeed be kept spinning if you move the held magnet out and force it back in again with the right timing. So I would guess that there is a magnet in the apparently wooden dowel where it passes through the casing, that the casing contains a coil of wire to form an electromagnet, and ... that the battery is small enough that I don't see where it is hidden. The device beneath the wheel doesn't have any apparent purpose, but I would suggest it somehow controls the electromagnet, either by a wire too thin to see on the video or by some more sophisticated means such as microphone, radio etc. picking up the contact. (Note: the comments on the video have a different opinion, that there is compressed air being blown at the device, and that it slows down before he turns it off for that reason, but I don't agree; there's not much for air to work on.) Wnt (talk) 17:54, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- I suppose you mean perpetual motion, not perceptual motion. OsmanRF34 (talk) 19:24, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- "This technology has been suppressed because it is a threat to the profits of the energy corporations", yeah right, where have we heard that before, it's the same refrain of every perpetual motion crank that ever was. If that's the case, how come the energy companies are allowing him to live and threaten their profits like this? SpinningSpark 19:36, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- I didn't watch the video, but there have been many claims of perpetual motion in approximately the past two centuries, since the law of conservation of energy was defined. They have, in my opinion, fallen into two subclasses, those which the so-called inventor actually believed were perpetual motion (in which case he was deluded), and those in which the so-called inventor was engaging in fraud. As Wnt explains, there is probably some hidden machinery involved. Robert McClenon (talk) 19:48, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- Given the inherent false premise "perceptual motion" is probably fitting. P.S. The OP is the Venezuelan troll. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 21:11, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- I didn't watch the video, but there have been many claims of perpetual motion in approximately the past two centuries, since the law of conservation of energy was defined. They have, in my opinion, fallen into two subclasses, those which the so-called inventor actually believed were perpetual motion (in which case he was deluded), and those in which the so-called inventor was engaging in fraud. As Wnt explains, there is probably some hidden machinery involved. Robert McClenon (talk) 19:48, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

In the hundreds of years that con-artists inventors have been producing perpetual motion devices, not one has stood up to scrutiny. Zzubnik (talk) 10:31, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- True, but like stage magic, just because you know it can't work doesn't mean you can't appreciate a good performance. Wnt (talk) 15:45, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- For sure this is a fake. We know this because (a) 100% of perpetual motion machine claims have been fakes - it's exceedingly unlikely that this one is not (b) about 90% of YouTube "science" videos are faked - and 100% of the "amazing" ones and (c) free energy nuts are obsessed with magnets because they don't understand them and feel that there must, obviously, be some way to extract the "obvious" energy from them. However, they don't understand the difference between "force" and "energy". Getting forces for free is easy - getting energy for free is impossible.

- The only remaining question is how they faked it...and there are a bazillion ways that could have happened. There is ample space within the frame and the drum to hide motors, batteries, electromagnets, air-jets, etc. There is also ample scope for camera trickery and computer graphics.

- The machine they are playing with is a simple variation of the SMOT - with the magnets wrapped around a drum and the vertically moving bar behaving like the ball in the regular SMOT. SMOTs don't work for very well-understood reasons....but they do *seem* to be coming very close to working - and that means that a lot of poorly-educated are "inventors" working insanely hard to eliminate friction or slightly tweak the setup in the hope of just getting it that tiny bit further to the point where it would run perpetually. Sadly, the smallest amount of understanding of the laws of thermodynamics would prevent this enormous waste of human effort...but that's not likely to happen.

- In the early parts of the video, (which may well *not* be faked), he's inadvertently supplying energy to the drum by pulling the metal bar away from and towards the drum. The energy required to do that will be more than it takes to accelerate the drum...so that could easily be real. However, in the final demonstration, where the bar is being lifted away by the cam that's driven by the drum, the cam would rob the spinning drum of kinetic energy faster than the falling piece of metal would increase it and the machine would stop within a few revolutions.

- Incidentally, a more efficient (but still non-functioning) machine would have the drum be the shape of the cam and the metal arm be stationary. This would eliminate the sliding friction and reduce the machine to a single moving part. But it still wouldn't work.

- Bottom line is that we know for 100% sure that this is a fake. It's exhausting to have to understand HOW it was faked - there are just too many of these bullshit videos and the idiots who present them seem to have boundless energy for fooling gullible people.

- If this were real, the "inventor" wouldn't be showing it to you on YouTube, he'd be selling it to the power generation companies for billions and billions of dollars.

- SteveBaker (talk) 17:03, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- It's remotely possible - but we'd still be talking Nobel Prize in Physics for sure, accolades throughout the future of humanity, BILLIONS of dollars in licensing fees from power companies, car manufacturers, etc. Writing for Wikipedia isn't remotely like that - for one thing, you can't just get a job writing encyclopedia articles - Brittannica are going down the toilet, the job never involved writing so much as editing what experts in the field wrote - and it just didn't ever pay much. Writing non-fiction books is similarly pointless...I've been invited to write tech books MANY times, and each time, I'd be earning less than minimum-wage to do it. A better comparison might be donating software to the OpenSource community - but then it's generally people who needed that software for their own purposes who decide to donate it so that other people will help to maintain it. The people who donate time to the Linux kernel are perhaps being more generous with their time - they could probably earn $50/hour doing it as a job. But finding a true, for real, working perpetual motion machine would make you more well known than Albert Einstein - a true saviour of the world - impossibly rich, respected by absolutely everyone.

- If this thing worked - we'd be seeing it all over the news...it would be the biggest story in the history of mankind...by far!

- However, it doesn't work because it can't possibly work - so it's not big news - and since it's one of a bazillion other faked YouTube 'science' videos - we can simply place it firmly on the "UTTER BULLSHIT" pile and move on with our lives.

- SteveBaker (talk) 14:39, 13 June 2014 (UTC)

- To be picky, whether a perpetual motion machine would get you money from power companies depends on which kind you're talking about. A perpetual motion machine of the third kind doesn't let you extract any useful work from it; it just keeps going and going. Our article claims that these are impossible too, but I think that's a harder case to make than for the first and second kinds. (For example, why isn't an electron in its orbit such a "machine"?) --Trovatore (talk) 04:07, 14 June 2014 (UTC)

- Isn't the point of a so-called "perpetual motion machine" to be able to extract energy or "work" from it without having to input anything? No human invention can do that, but the forces of nature, the sun in particular, can do that. The sun is not literally perpetual, i.e. it will die eventually, but presumably long after we do, so for practical purposes, it qualifies. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 05:00, 14 June 2014 (UTC)

- @Bugs: Your reply is incorrect in every regard. You really need to read the perpetual motion article before discussing this subject. The sun isn't remotely a perpetual motion machine. "Perpetual" means "forever" and not just "for a very long time". A hypothetical machine that runs perpetually WITHOUT the ability to generate excess energy is still a perpetual motion machine "of the third kind"...although such devices couldn't exist as practical devices in the real universe even though the laws of thermodynamics don't prohibit them. SteveBaker (talk) 16:34, 14 June 2014 (UTC)

- There's a lot of things that qualify as "essentially perpetual motion": the rotation of the Earth, ocean currents, wind, geothermal energy, sunshine, storms - we can even harness some of these, and odds are that none of these will stop without man also being extinct. However, I think the appeal of a perpetual motion machine isn't so much "it never runs out of energy to harvest", but "we can manufacture, organize, and control them" - the power we can get from natural, effectively endless supplies, is not something we can easily control, nor is something that we can stick in a building, etc. --Note: obviously perpetual motion machines do not exist, though, it may be possible to achieve the same ends, somehow, eventually by tapping into natural sources. --@Steve: yes, the sun isn't actually perpetual, but if we're here for the sun running out of energy, I doubt we'll be here much longer.Phoenixia1177 (talk) 16:50, 14 June 2014 (UTC)

- Reading the article about perpetual motion, the sun qualifies. "Perpetual" means "permanent", and nothing in the universe is literally permanent. When they hire you for a "permanent" position, that doesn't literally mean it won't end for you. And in fact it will end a lot sooner than the sun will. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 17:11, 14 June 2014 (UTC)

- Baseball Bugs is redefining perpetual motion from its nineteenth-century through twenty-first century meaning to mean "almost permanent" or "effectively permanent" rather than "permanent". Solar and wind power were considered perpetual motion prior to the formulation of the law of conservation of energy (first law of thermodynamics) in the nineteenth century. To modern scientists, solar and wind power are not perpetual motion, simply effective clean sources of energy not requiring fuel. The device that started this thread was claimed to be true perpetual motion, and such claims are either deluded or fraudulent. Nice try by Bugs at redefining terminology, but it isn't scientific. Robert McClenon (talk) 17:26, 14 June 2014 (UTC)

- Reading the article about perpetual motion, the sun qualifies. "Perpetual" means "permanent", and nothing in the universe is literally permanent. When they hire you for a "permanent" position, that doesn't literally mean it won't end for you. And in fact it will end a lot sooner than the sun will. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 17:11, 14 June 2014 (UTC)

- @Trovatore: True, but any practical machine which sits on the top of your desk and does it's thing like that is clearly "of the first kind" because it must encounter air resistance and friction, and it makes sound as it spins - so at the very least, it's definitely going to generate a small amount of heat. Putting the gizmo in the video (if it wasn't an obvious fake!) into a closed box would result in the box spontaneously and continuously getting hotter - you could use that heat to generate electricity and thereby extract useful work from it. A perpetual motion machine of the third kind could only ever be a thought experiment because no matter where you put it (even out in the depths of space), there would always be odd molecules evaporating from it's surface and resulting in a tiny amount of resistance that would eventually bring it to a halt. Moreover, the machine in the video clearly accelerates - and that means that it generates torque in excess of slow-speed friction - so it has the capability to drive some other gizmo that would extract energy. So while I agree that a hypothetical third kind perpetual motion machine wouldn't interest the energy companies, absolutely any practical machine that demonstrates perpetual motion really would interest them. But it's not going to happen. SteveBaker (talk) 16:28, 14 June 2014 (UTC)

- Isn't the point of a so-called "perpetual motion machine" to be able to extract energy or "work" from it without having to input anything? No human invention can do that, but the forces of nature, the sun in particular, can do that. The sun is not literally perpetual, i.e. it will die eventually, but presumably long after we do, so for practical purposes, it qualifies. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 05:00, 14 June 2014 (UTC)

- To be picky, whether a perpetual motion machine would get you money from power companies depends on which kind you're talking about. A perpetual motion machine of the third kind doesn't let you extract any useful work from it; it just keeps going and going. Our article claims that these are impossible too, but I think that's a harder case to make than for the first and second kinds. (For example, why isn't an electron in its orbit such a "machine"?) --Trovatore (talk) 04:07, 14 June 2014 (UTC)

- Well, NASA believes enough in an Alcubierre drive that it is showing kids a mock-up of the thing and posturing that it has a hope of achieving warp drive some day. Now correct me if I'm mistaken, but I believe that if you could create even a microscopic warp bubble in the lab, emitting it off into the ether (where it might or might not even be part of our universe any more) you are going to be creating large amounts of dark energy in that new warp-bubble space out of nothing. Is there a way to tap into that and use the production of empty warp bubbles as a source of unlimited free "real" energy? Wnt (talk) 18:40, 14 June 2014 (UTC)

- There are a lot of difficulties with making such a warp drive (perhaps insurmountable ones). Setting that aside, I don't follow about why it would create large amounts of dark energy - do you have a link to a paper/website that explains that out in more detail?Phoenixia1177 (talk) 00:51, 15 June 2014 (UTC)

- No, sorry - I thought it was a given that dark energy pervades all space equally, and when space expands more dark matter is created, so this warp bubble I thought would be the same thing. Alternatively, if the warp bubble doesn't create dark energy, would there be any way to "charge a toll" on the dark energy rushing into it? Wnt (talk) 06:23, 15 June 2014 (UTC)

- There are a lot of difficulties with making such a warp drive (perhaps insurmountable ones). Setting that aside, I don't follow about why it would create large amounts of dark energy - do you have a link to a paper/website that explains that out in more detail?Phoenixia1177 (talk) 00:51, 15 June 2014 (UTC)

Why does everything look green through night vision goggles?

Or in TV series or movies where night vision equipment is used? I looked at the appropriate articles and even using CTRL-F I couldn't even find the word "green". I was mainly interested in why on Riot (TV series) the green is a different shade than in other situations. I asked a question here but have a feeling no one will read it without my trying another method.— Vchimpanzee · talk · contributions · 21:14, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- This article[4] explains how these goggles work and why everything looks green. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 21:26, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- Thank you, and I don't have time to do this now, but would this be an appropriate source for Wikipedia, which I think should have the information?— Vchimpanzee · talk · contributions · 21:28, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- They skipped over the obvious bit, though, that night vision goggles only see in monochrome, because there isn't enough light at night for lenses that size to gather enough light to distinguish colors at a reasonable cost and weight. Our eyes have the same problem in dim light. So, they needed to choose black and one color, or possibly black and white, to display the image. They could also use a rainbow coloring scheme like an infrared camera sometimes does, where hotter spots in the image are redder and cooler areas are bluer (in this case brighter areas would be one color and dimmer colors another). Of those options, that link explains why they chose green, which seems to be to conserve energy. StuRat (talk) 21:34, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- No. Just...no. That's not the way an image intensifier works. These are solid-state analog devices from front to back, with no place to insert false-color imaging. What you see at the eyepiece is the direct output from a phosphor screen; there isn't a little LCD display in there. In principle one could take the output of this system and couple it to another imaging sensor to allow downstream processing, analysis, false-coloring, etc.—but it would add cost, complexity, weight, fragility, energy consumption, and noise, while slightly reducing sensitivity: tradeoffs not generally deemed worthwhile for devices intended to be portable (even head-mounted) and used in the field.

- The not-enough-light-to-distinguish-colors bit is some creative nonsense. While splitting or filtering the incoming light into multiple color channels would cost some sensitivity, the low-light sensitivity of photocathode materials has improved remarkably over the last seventy years, and the efficiency and quality of the electron multipliers has improved almost unbelievably. The hard part would be either coupling the correctly-'colored' photocathode 'sensor' spot on the front of the device to the matching colored phosphor on the back, through the microchannel plate—or splitting incoming light into three separate light paths that could be amplified separately and recombined. Either route to 'color' vision would be costly and complex, and not worth the tradeoffs (see above). There is also the question of what colors to display—one of the most useful tricks these devices generally perform is sensitivity to ambient infrared light (out to 900 or 950 nm, give or take). If you were to display those red and infrared sources in red on the display, you would be taking the best and brightest light in your scene and displaying it in a color where the human eye is less sensitive, which seems a poor trade. TenOfAllTrades(talk) 13:09, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- I added "at a reasonable cost and weight" to my above explanation. Yes, they could have a full color display, but the technology level isn't quite up to doing so at a reasonable price and weight, yet. At some point in the future, we probably will have full color night vision goggles, with digital displays, although I bet they will still have a monochrome option for when the light level is extremely low. Also, a monochrome display may overcome some types of camo, and a color display others, so being able to switch would be useful. StuRat (talk) 13:55, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- Something tells me we're not going to have the answer on Wikipedia anytime soon.— Vchimpanzee · talk · contributions · 17:19, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- Having some experience in this from my past career in detection and counterdetection, I can shed some light. (ahem)

- The answer to "why does everything look green", or more specifically, "why do night vision devices always use a monochrome green display instead of some other color", is answered quite nicely in the link Baseball Bugs posted above.

- The answer to "why can't it be a color display" should be obvious. When wearing a night vision device, you want the display to be as dim as possible, for two reasons: (a) you want your eyes to remain useful and dark-acclimated if you remove the device, and (b) any leakage should be as dim as possible to prevent counter-detection.

- Therefore, the night vision display should be as dim as possible but still bright enough to discern light and shadow properly. This is best done with a green wavelength, to which the human eye is most sensitive. If the display showed colors, then the display would have to be much brighter for you to discern any colors at all. The usefulness of having colors does not outweigh the disadvantages of having a brighter display. ~Amatulić (talk) 17:37, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

Any thoughts on why the color is different on Riot?— Vchimpanzee · talk · contributions · 21:53, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

Recover 1950s sound

Will it be possible to recover better sound from video recordings made of singers in the 1950s? This example at 17:34 sung by Gene Vincent may have suffered distortion as an optical soundtrack in a Kinescope process. Is this a non-linear distortion that could be corrected by modern processing? 84.209.89.214 (talk) 23:57, 11 June 2014 (UTC)

- Does the article Remaster lead you anywhere? --Jayron32 00:12, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- The example is typical of pre-digital analog recordings where there is no earlier generation available. Remastering techniques can sharpen and even colorize the video but the question is about recovering the sound, especially that of the instruments accompanying the singer. 84.209.89.214 (talk) 01:14, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- Yes, they could restore it, to some degree, but the question is if it would pay to do so. That is, would they be able to sell the cleaned up recording at a profit ? StuRat (talk) 03:07, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- Please explain what technique you claim will work. This OP is not asking for a Business case case for some nebulous "them" to invest in Rockabilly music. 84.209.89.214 (talk) 13:27, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- I don't understand the connection between the audio distortion and the Kinescope process. From reading the Kinescope article, I expect the audio to have been handled separately from the video. The audio distortion may not have anything to do with the Kinescope process per se. In your question, you asked about "recovering" better sound. I would distinguish between reducing the distortion (i.e. making the processed signal closer to the original) and reducing the artifacts (i.e. making the processed signal subjectively better but not necessarily closer to the original). Some types of distortion (e.g. band-pass filtering, clipping) can cause information loss, making it not possible to actually recover the lost information. Something can probably be done to make the recording sound better by reducing the artifacts, but I'm not familiar with the techniques that have been developed. --173.49.79.84 (talk) 10:31, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- Well, a program could recognize that a particular note is supposed to be at a certain frequency, and produced by a certain instrument, then substitute in the "correct" sound for that note. If the frequencies are off a bit it could assume that the nearest note on the scale is the correct one. When a single instrument was playing one note at a time, this would be relatively simple. Adding chords and multiple instruments playing over each other would make it more complex to take this approach.

- Another approach to deal with short gaps would be to fill in the gap with notes that change from the last good sound before the gap to the first good sound after the gap.

- Note that either of these approaches would benefit from a human at the controls, to tell the program when it gets something wrong and try to fix it manually. In the case of the worst recordings, though, this would be more like the person recognizing what was recorded, and then recording a new version of that song, than actually restoring the original. At some point, there's so little of the original left, that this is the best you can do. StuRat (talk) 13:45, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- I imagine that we should be nearing the point where we can accurately model a human vocal apparatus and all the relevant musical instruments and their position in a room, and have a computer optimize the model to match the recording. Has anyone tried to do it yet? Wnt (talk) 15:48, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- Your program would need to do quite a bit more than that. The performance of music is more than just a standardized, mechanical translation of musical scores into sound. (Otherwise, there's no point in having more than one recording of the same musical piece by multiple performers.) Your program would need to detect those "parameters" of a performance whose variation give rise to the personal styles of individual performers, and do that correctly despite the distortion in the original recording. Finally your program would need to synthesize an undegraded performance based on those detected style-defining parameters. This last part is probably the easier part of the job. --173.49.79.84 (talk) 23:33, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- All this is true to get a perfect restoration, but it might also be of value to get a restoration that, while not perfect, is still better than the degraded version. StuRat (talk) 14:19, 13 June 2014 (UTC)

- 173.49.79.84, optical soundtracks encoded on film were common, but our Kinescope article only has a few sentences on it. Katie R (talk) 17:46, 12 June 2014 (UTC)

- When I wrote that I expected the audio to have been handled separately from the video, I meant that the recording of audio onto an optical soundtrack was not subject to the problems that affected the video. --173.49.79.84 (talk) 23:33, 12 June 2014 (UTC)