User:LightandDark2000/My Notable Storms

| |

| Wikipedia ads | file info – #84 |

Hello, I am LightandDark2000. This is the page in which I will post my featured storms. Each storm is categorized by a notable characteristic that sets them apart, and the storms are listed in chronological order in their own respective sections. Note that while some storms may have characteristics that match multiple categories, each storm is only listed once on this page. The contents are subject to change, so please do not be upset if something "disappears." However, if the storm I erased was a major storm, chances are I'll put it back up later. Additionally, if you want to check out active tropical cyclones or the various tropical cyclone basins, see Portal:Tropical cyclones. Enjoy!

Timeline of Unusually occurring & Long-lived storms

[edit]

Storm of the Year

[edit]Featured Storm Number 12 – November 3, 2020

The Storm of the Year – 2020

Hurricane Eta

[edit]| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 28, 2020 – November 14, 2020 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-min); 923 mbar (hPa) |

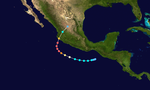

Eta was a powerful and long-lived hurricane that devastated Central America in November 2020. The twenty-ninth tropical depression, record-tying twenty-eighth named storm, twelfth hurricane, and fifth major hurricane of the extremely active 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, Eta originated from a vigorous tropical wave in the eastern Caribbean Sea on October 28. On October 30, the system organized into Tropical Depression Twenty-Nine,[1] before becoming a tropical storm on the next day, at which time it was given the name Eta by the National Hurricane Center (NHC).[2] On November 2, Eta became undergoing rapid intensification over the western Caribbean, as it progressed westward, with the cyclone ultimately becoming a Category 4 hurricane on November 3.[3][4] Later that day, Eta reached its peak intensity, with 1-minute sustained winds of 150 mph (240 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 923 mbar (hPa; 27.26 inHg), it was the third most intense November Atlantic hurricane on record, behind the 1932 Cuba hurricane, and Hurricane Iota, which struck the same region just two weeks later.[5] However, satellite data suggests that Eta may have reached Category 5 intensity at the time of its peak intensity, since reconnaissance aircraft failed to sample the hurricane's strongest winds at the time of its peak intensity, and multiple meteorologists believed that Eta peaked as a Category 5 hurricane;[6] this possibility is awaiting evaluation from the NHC in their post-storm report, which should be released by Spring 2021. However, six hours after reaching its peak, Eta underwent an eyewall replacement cycle, causing the storm to weaken somewhat. At 21:00 UTC on November 2, Eta made landfall south of Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua, with maximum sustained winds of 140 mph (225 km/h) and a central pressure of 940 mbar (hPa; 27.76 inHg).[7] Following landfall, Eta rapidly weakened to a tropical depression by 00:00 UTC on November 5.

Despite the mountainous terrain, Eta's low-level circulation survived, and Eta retained tropical depression status for the remainder of its two-day trek across Central America, before moving north over water on November 6, and turning towards the northeast.[8] Afterward, Eta reorganized into a tropical storm over the Caribbean on November 7, as it accelerated toward Cuba.[9] On the next day, Eta made landfall on Cuba's Sancti Spíritus Province as a tropical storm, before quickly emerging into the Atlantic and turning westward.[10] Over the next five days, the system moved erratically, making a third landfall on Lower Matecumbe Key in the Florida Keys, on November 9,[11] before slowing down and making a counterclockwise loop in the southern Gulf of Mexico, just off the coast of Cuba, with the storm's intensity fluctuating along the way. Afterward, Eta turned north-northeastward and briefly regained Category 1 hurricane strength on November 11,[12] before weakening back into a tropical storm several hours later.[13] On November 12, Eta made a fourth and final landfall over Cedar Key, Florida.[14] Eta weakened after making landfall, before eventually re-emerging into the Atlantic later that day.[15] Afterward, Eta became extratropical on November 13,[16] before being absorbed into another frontal system off the coast of the Eastern United States on the next day.[17] In all, Hurricane Eta killed at least 211 people, left 120 people missing, and caused at least $7.9 billion (2020 USD) in damages, with the vast majority of the deaths and damages occurring in Central America.[18] Just two weeks later, Central America was struck by Hurricane Iota as a high-end Category 4 hurricane, making landfall near the same location as Eta, which further exacerbated the disaster in the region.

Juggernauts

[edit]Super Typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda)

[edit]| Violent typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 5 super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | November 3, 2013 – November 11, 2013 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 230 km/h (145 mph) (10-min); 895 hPa (mbar) |

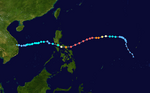

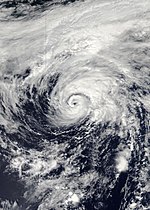

On November 3, a low-pressure area formed 45 nautical miles south-southeast of Pohnpei. The Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) issued a Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert. A few hours later, the JTWC designated the depression as "31W". At 10 AM JST the next day, the JMA named 31W as Haiyan. Haiyan rapidly intensified as it headed towards Palau and the Philippines. Rapid deepening occurred and it became a Category 5 Super Typhoon as it entered the Philippine area of responsibility[clarification needed], and was named Yolanda. Haiyan reached a barometric pressure below 900 mbars (895 mbars), the first since Typhoon Megi in 2010. At one of the evacuation centers the storm brought down the roof of a church in Leyte resulting in at least 20 deaths.[19]

A total of 905,353 people have been affected by the typhoon since late November 7. Later that day, the death toll rose to three.[20] During the afternoon of November 8, the death toll rose to 23. On November 9, it was reported that a total of 56 were dead as Haiyan moved across the central Philippines.[21] Haiyan made landfall in Guiuan, Eastern Samar at 04:45am 2013 (UTC). More than 30 trees were uprooted during that time and no casualties have been reported. State forecasters said that nearly 800,000 people were forced to flee their homes and damage was believed to be extensive. About four million people were affected.[22] In some places in Central Visayas, school will reopen on November 15. It was reported that there was one dead and one injured in Batangas due to high waves which is now a total of 139.[23] A total of 71,623 families (330,914 persons) are being served inside 1,223 evacuation centers during that time.[24] On November 10, 11,000 houses were reported destroyed in Aklan with seven casualties and the death toll rose to 151.[25] The NDRRMC reported that a total of 255 people died from Typhoon Yolanda on November 11. By 0900 UTC, November 11, estimates rose to over 10,000 deaths, with the vast majority in Tacloban.[26]

On November 8, Haiyan weaken to a Category 4 typhoon as it entered the South China Sea. An eyewall replacement cycle occurred to Haiyan as it became a Category 3 typhoon. On November 9, the outer rainbands of the storm was felt in Cambodia and Vietnam. It weaken to a moderate typhoon as it was also felt in Laos. Haiyan rapidly weakened to a severe tropical storm as it killed 12 people in China on November 10. Late on November 11, Haiyan dissipated inland.

- Note: Haiyan was Storm of the Year for 2013.

Super Typhoon Meranti (Ferdie)

[edit]| Violent typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 5 super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 8 – September 17, 2016 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 220 km/h (140 mph) (10-min); 890 hPa (mbar) |

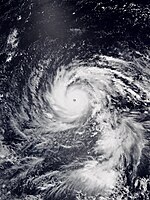

On September 8, 2016, a tropical depression formed[27] in a region of low wind shear, steered by ridges to the north and southwest, with warm water temperatures and outflow from the south.[28] The system reached tropical storm strength by 06:00 UTC on September 10, receiving the name Meranti.[29]

Rainbands and a central dense overcast continued to evolve as the wind shear decreased.[30] By early on September 12, Meranti reached typhoon status.[31] A small eye 9 km (5.6 mi) across developed within the spiraling thunderstorms, and Meranti started rapidly intensifying.[32] Meranti quickly attained estimated 1-minute sustained winds of 285 km/h (180 mph), equivalent to Category 5 on the Saffir–Simpson scale.[33] Meranti gradually reached its peak intensity on September 13 while passing through the Luzon Strait. The Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA)[a] estimated peak 10-minute sustained winds of 220 km/h (140 mph) and a minimum barometric pressure of 890 hPa (mbar; 26.28 inHg),[34] while the Joint Typhoon Warning Center[b] estimated peak 1-minute sustained winds of 305 km/h (190 mph).[36] Based on the JMA pressure estimate, Meranti was among the most intense tropical cyclones. The JTWC wind estimate made Meranti the strongest tropical cyclone worldwide in 2016, surpassing Cyclone Winston, which had winds of 285 km/h (180 mph) when it struck Fiji in February.[37]

Late on September 13, the storm made landfall on the 83 km2 (32 sq mi) island of Itbayat in the Philippine province of Batanes while near its peak intensity.[38] At around 03:05 CST on September 15 (19:05 UTC on September 14), Meranti made landfall over Xiang'an District, Xiamen in Fujian, China with measured 2-minute sustained winds of 173 km/h (108 mph),[39] making it the strongest typhoon to ever make landfall in China's Fujian Province.[40] The system rapidly weakened soon after making landfall, while curving toward the northeast, degenerating into a tropical depression later in the day. On the next day, the system weakened into a remnant low, and re-emerged into the East China Sea. Meranti's remnant low dissipated on September 17.

Super Typhoon Mangkhut (Ompong)

[edit]| Violent typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 5 super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 7 – September 17, 2018 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 205 km/h (125 mph) (10-min); 905 hPa (mbar) |

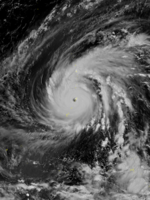

On September 7, a tropical depression formed near the Marshall Islands, and the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) initiated advisories on the system. The JTWC followed suit at 03:00 UTC, and the system was classified as 26W. Late on the same day, the system strengthened into a tropical storm, and the JMA named the system Mangkhut. By September 11, Mangkhut became a typhoon, and made landfall on the islands of Rota, Northern Mariana Islands. On September 12, at 3 pm Philippine Standard Time, Typhoon Mangkhut entered the PAR as a Category 5 super typhoon, and accordingly, PAGASA named the storm Ompong. The JTWC noted additional strengthening on September 12, and assessed Mangkhut to have reached its peak intensity at 18:00 UTC, with maximum one-minute sustained winds of 285 km/h (180 mph). On September 13, the Philippine Government initiated evacuations for residents in the typhoon's expected path. Late on September 14, Mangkhut made landfall on the Philippines as a Category 5-equivalent super typhoon, with 1-minute sustained winds of 165 miles per hour (266 km/h).[41] While moving inland, Mangkhut weakened into a strong Category 4-equivalent super typhoon, and soon weakened further into a Category 2 typhoon. A large eye then appeared and the system slowly strengthened into a Category 3 typhoon, as the storm moved over Hong Kong. As Mangkhut made its final landfall, it weakened into a weak Category 1 typhoon and maintained its intensity inland with deep convection, before subsequently weakening further. Late on September 17, Mangkhut dissipated over Guangxi, China.

As of September 23, 2018, at least 134 fatalities have been attributed to Mangkhut, including 127 in the Philippines,[42][43] 6 in mainland China,[44] and 1 in Taiwan.[45] As of October 5, the NDRRMC estimated that Mangkhut caused ₱33.9 billion (US$627 million) in damages in the Philippines, with assessments continuing.[46]

Super Typhoon Goni (Rolly)

[edit]| Violent typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 5 super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 26, 2020 – November 6, 2020 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 220 km/h (140 mph) (10-min); 905 hPa (mbar) |

The nineteenth named storm, ninth typhoon, and second super typhoon of the 2020 Pacific typhoon season, Goni originated as a tropical depression south portion of Guam on October 26. It was then named as Tropical Storm Goni on October 27. On the next day, Goni explosively intensified over the Philippine Sea, becoming a Category 5–equivalent super typhoon on October 30. Goni maintained Category 5 strength for over a day, before making landfall on Catanduanes at peak intensity, with 10-minute sustained winds of 220 km/h (140 mph),[47] and 1-minute sustained winds of 315 km/h (195 mph), with a minimum central pressure of 905 hPa (mbar; 26.72 inHg). It was the most intense tropical cyclone observed worldwide in 2020, and one of the most intense tropical cyclones on record.[48] Following its first landfall, Goni rapidly weakened while it moved over the Philippines. Over the next day, Goni made three more landfalls over the Philippines, while continuing to weaken. On November 2, Goni moved into the South China Sea and weakened to a tropical storm. It then moved westward towards Vietnam. Late on November 5, Goni made landfall on Vietnam, as a tropical depression, bringing heavy rain and gusty winds.

The storm brought severe flash flooding to Legazpi, as well as lahar flow from the nearby Mayon Volcano. There were widespread power outages as well as damaged power and transmission lines in Bicol. Crops were also heavily damaged. Over 390,000 out of 1 million evacuated individuals have been displaced in the region. Due to the extreme wind speed of the typhoon, two evacuation shelters had their roofing lost. Debris and lahars had also blocked various roads, as well as rendering the Basud Bridge impassible. In Vietnam, where Goni made landfall as a tropical depression, there was flooding in numerous areas, as well as eroded and damaged roads. This exacerbated the 2020 Central Vietnam floods, causing an estiamted ₫543 billion (US$23.5 million). In all, the typhoon killed at least 32 people and caused at least ₱20 billion (US$415 million) worth of damage.[18] The COVID-19 pandemic was also a concern for people in evacuation centers.[49] International relief from several countries as well as the United Nations followed soon after the typhoon moved away from the Philippines.[50] The relief included donations totaling up to $11.48 million and protection from the pandemic, among other items. Due to the damage caused by the typhoon, the names Goni and Rolly were retired.

Monsters of Destruction

[edit]Hurricane Mitch (1998)

[edit]| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 10, 1998 – November 9, 1998 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 180 mph (285 km/h) (1-min); 905 mbar (hPa) |

Tropical Depression Thirteen was spawned by a tropical wave on October 22, while located offshore Colombia in the Caribbean Sea. Later that day, the depression became Tropical Storm Mitch, and within two days it intensified into a hurricane. While curving westward, the storm rapidly deepened, reaching its peak as a Category 5 hurricane with winds of 180 mph (285 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 905 mbar (26.7 inHg) late on October 26. Mitch weakened significantly while turning to the south, and on October 29 it moved ashore with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) east of La Ceiba, Honduras. It quickly weakened to a tropical storm, but did not deteriorate into a tropical depression until October 31 while over Central America. Mitch degenerated into a low pressure area on November 2 near the border of Mexico and Guatemala, although it was re-designated a tropical storm on November 3, after emerging into the Bay of Campeche. After turning to the northeast, the storm struck the city of Campeche early on November 4, and Mitch briefly weakened into a tropical depression over the Yucatán Peninsula. The storm re-intensified after reaching the Gulf of Mexico again, and Mitch made its final landfall near Naples, Florida with winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) on November 5. Shortly thereafter the storm became extratropical near the northern Bahamas, which lasted several more days while crossing the Atlantic Ocean.[51]

Heavy rainfall in Jamaica flooded numerous houses and caused three fatalities from mudslides.[52][53] Strong winds, rough seas, and large amounts of precipitation resulted in minor effects in Cuba and the Cayman Islands.[53][54] Offshore Honduras, the Fantome sank, drowning all 31 people on board. In Honduras, the large and slow-moving storm dropped 35.89 inches (912 mm) of rain,[51] causing the destruction of at least 70% of the country's crops and an estimated 70-80% of road infrastructure. About 25 villages were completely dismantled, while about 33,000 homes were destroyed and another 50,000 were damaged.[52] Damage totaled about $3.8 billion in Honduras and at least 14,600 fatalities were reported.[55] In Nicaragua, rainfall totals may have reached 50 inches (1,300 mm). Over 1,700 miles (2,700 km) of roads required replacement or repairs, while effects to agriculture were significant.[52] Almost 24,000 houses were destroyed and an additional 17,600 were damaged.[56] About 3,800 deaths and $1 billion in damage were reported in Nicaragua.[52] In Costa Rica, the storm impacted 2,135 homes, of which 241 were destroyed. Extensive road infrastructure and crop damage was also reported. There were 7 people killed and $92 million in damage in Costa Rica.[57]

The storm caused flooding as far south as Panama, where three fatalities occurred.[52] Flash flooding and landslides in El Salvador damaged more than 10,000 homes, 1,200 miles (1,900 km) of roadway, and caused heavy losses to crops and livestock.[58] Damage totaled $400 million and 240 deaths were confirmed. Effects were similar but slightly more significant in Guatemala, where 6,000 houses were destroyed and an additional 20,000 were impacted to some degree. Additionally, 840 miles (1,350 km) of roads were affected, with nearly 400 miles (640 km) of it being major highways. Crop damage in Guatemala alone was nearly $500 million. It was reported that 268 deaths and $748 million in losses occurred in Guatemala.[59] The storm caused relatively minor effects in Mexico and Belize, with 9 and 11 fatalities in both countries, respectively.[52] Mitch brought tropical storm winds to South Florida and rainfall up to 11.20 inches (284 mm).[51] In the Florida Keys, several buildings that were damaged by Georges were destroyed by Mitch. Tornadoes in the state spawned by Mitch damaged or destroyed 645 houses.[52] The storm caused two fatalities and $40 million in damage in Florida.[51] Overall, Mitch caused $6.2 billion in losses and at least 18,974 people were left dead.[55][51][52][57][58][59]

Hurricane Ivan (2004)

[edit]| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 2, 2004 – September 24, 2004 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 165 mph (270 km/h) (1-min); 910 mbar (hPa) |

A westward-moving tropical wave developed into a tropical depression on September 2, before becoming Tropical Storm Ivan on the following day. After reaching hurricane intensity on September 5, the storm strengthened significantly, becoming a Category 4 hurricane on September 6. It subsequently weakened, though it reached major hurricane status again the next day. Late on September 7, Ivan passed close to Grenada while heading west-northwestward. While located near the Netherlands Antilles on September 9, Ivan briefly became a Category 5 hurricane. During the next five days, Ivan fluctuated between a Category 4 and 5 hurricane. The storm passed south of Jamaica on September 11 and then the Cayman Islands on the next day. While curving northwestward, Ivan brushed western Cuba as a Category 5 hurricane on September 14.[60]

Shortly after moving to the west of Cuba on September 14, Ivan entered the Gulf of Mexico. Over the next two days, the storm gradually weakened while tracking north-northwestward and northward. At 06:50 UTC on September 16, Ivan made landfall near Gulf Shores, Alabama with winds of 120 mph (195 km/h). It quickly weakened inland, falling to tropical storm status later that day and tropical depression strength by early on September 17. The storm curved northeastward and eventually reached the Delmarva Peninsula, where it became extratropical on September 18. The remnants of Ivan moved southward and then southwestward, crossing Florida on September 21 and re-entering the Gulf of Mexico later that day. Late on September 22, the remnants regenerated into Ivan in the central Gulf of Mexico as a tropical depression, shortly before re-strengthening into a tropical storm. After reaching winds of 65 mph (100 km/h), wind shear weakened Ivan back to a tropical depression on September 24. Shortly thereafter, Ivan made a final landfall near Holly Beach, Louisiana with winds of 35 mph (55 km/h) and subsequently dissipated hours later.[60]

Throughout the Lesser Antilles and in Venezuela, Ivan caused 44 deaths and slightly more than $1.15 billion in losses, with nearly all of the damage and fatalities in Grenada.[60] While Ivan was passing south of Hispaniola, the outer bands of the storm caused four deaths in the Dominican Republic. In Jamaica, high winds and heavy rainfall left $360 million in damage and killed 17 people.[60] The storm brought strong winds to the Cayman Islands, resulting in two deaths and $3.5 billion in damage. In Cuba, a combination of rainfall, storm surge, and winds resulted in $1.2 billion in damage, but no fatalities. Heavy damage was reported along the Gulf Coast of the United States. Along the waterfront of Escambia and Santa Rosa counties in Florida, nearly every structure was impacted. In the former, 10,000 roofs were damaged or destroyed. About 4,600 homes were demolished in the county.[61] Similar impact occurred in Alabama. Property damage was major along Perdido Bay, Big Lagoon, Bayou Grande, Pensacola Bay and Escambia Bay. A number of homes were completely washed away by the high surge. Further inland, thousands of other houses were damaged or destroyed in many counties. Ivan produced a record tornado outbreak, with at least 119 twisters spawned collectively in nine states.[62] Throughout the United States, the hurricane left 54 fatalities and slightly more than $18.8 billion in damage.[60] Six deaths were also reported in Atlantic Canada.[63]

Hurricane Katrina (2005)

[edit]| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 23, 2005 – August 31, 2005 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 175 mph (280 km/h) (1-min); 902 mbar (hPa) |

An area of disturbed weather over the Bahamas developed into a tropical depression on August 23, becoming a tropical storm on August 24 and a hurricane on August 25. It made landfall on August 25 in southern Florida, emerging a few hours later into the Gulf of Mexico. Katrina rapidly intensified to Category 5 status on the morning of August 28, becoming the fourth most intense recorded hurricane in the Atlantic basin. The hurricane weakened to a Category 4 as it turned northward, and weakened to a Category 3 hurricane with 125 mph (200 km/h) winds as it made landfall in southeastern Louisiana (as confirmed by the post-storm report; initially it was estimated as a Category 4 landfall). Hours later, it crossed the Breton Sound and held its strength, making its third and final landfall with 120 mph (190 km/h) winds near Pearlington, Mississippi.[64]

The Mississippi and Alabama coastlines suffered catastrophic damage from the storm's 30-foot (9m) storm surge. New Orleans escaped the worst damage from the storm, but levees along the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway and 17th Street and London Avenue Canals were ultimately breached by storm surge, flooding about 80% of the city. 1,836 people were confirmed dead across seven US states. Katrina is the costliest and one of the deadliest natural disasters in U.S. history, with damage totals around US $108 billion ($168 billion 2024 USD). It was the deadliest storm of the 2005 season. The damage and fatality estimates remain incomplete, as of late 2005.[64]

- The NHC's archive on Hurricane Katrina

- The WPC's archive on Hurricane Katrina

Extremely Severe Cyclonic Storm Nargis (2008)

[edit]| Extremely severe cyclonic storm (IMD) | |

| Category 4 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | April 27, 2008 – May 3, 2008 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 165 km/h (105 mph) (3-min); 962 hPa (mbar) |

In late April, the Intertropical Convergence Zone became very active over the Bay of Bengal and later spawned a low-pressure area on April 26. Accompanied by low wind shear, favorable outflow, and over an area of high sea surface temperatures, the system consolidated into a depression the following day. Tracking slowly westward, the depression intensified, becoming Cyclonic Storm Nargis on April 28. That day, steering currents weakened, causing the system to become nearly stationary before a trough influenced more northeasterly, and later easterly, movement. On April 29, the system attained hurricane-force winds. Hours before striking southern Myanmar on May 2, Nargis attained its peak intensity with winds of 165 km/h (105 mph) and an estimated central pressure of 962 mbar (hPa; 28.41 inHg).[65] The JTWC estimated the system to have been somewhat stronger, attaining one-minute sustained winds of 215 km/h (135 mph).[66] Once onshore, the system gradually weakened and dissipated early on May 4.[65][66]

Striking the Irrawaddy Delta with unprecedented intensity, Nargis produced a devastating 3 to 5 m (9.8 to 16.4 ft) storm surge over the region and a maximum wind speed of 190 km/h (120 mph) was also reported. Approximately 23,500 km2 (14,600 mi2) of land was inundated by the storm, affecting roughly 11 million people, 2.4 million severely.[65][67] Infrastructural impacts were tremendous, with 450,000 homes, 4,000 schools, and 75 percent of healthcare facilities destroyed and 350,000 homes severely damaged.[67] With approximately 138,373 fatalities taking place in Myanmar, Nargis is regarded as the worst disaster in the country's history and ranks as the sixth-deadliest tropical cyclone on record.[67][68] Damage from the storm amounted to K13 trillion (US$12.9 billion), the majority of which occurred within the private sector.[69]

In the immediate aftermath of the cyclone, numerous members of the international community were prepared to provide Myanmar with aid. For several weeks, the State Peace and Development Council (Myanmar's military junta) insisted that the nation could cope with the disaster and refused aid. This was soon determined to be ignorance of the situation and put millions of lives at risk. Some reports indicated that the army even obstructed private relief, setting up check-points, confiscating goods, and arresting those trying to help. In 2009, it was stated that the actions of the government could be condemned as crimes against humanity for "intentionally causing great suffering, or serious injury to body or to mental or physical health."[70]

Hurricane Matthew (2016)

[edit]| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 22, 2016 – October 10, 2016 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 165 mph (270 km/h) (1-min); 934 mbar (hPa) |

A vigorous tropical wave moved off the coast of Africa on September 22 and moved rapidly across the Atlantic, being monitored by the National Hurricane Center (NHC) for possible tropical cyclogenesis Despite possessing tropical-storm winds as it approached the Lesser Antilles on September 27, the wave could not initially be classified as a tropical cyclone, as reconnaissance aircraft could not find a closed center. However, on September 28, the tropical wave developed a closed low-level circulation while located near Barbados, and intensified into Tropical Storm Matthew. Continuing westward under the influence of a mid-level ridge, the storm steadily intensified to attain hurricane intensity by 18:00 UTC on September 29. The effects of southwesterly wind shear unexpectedly abated late that day, and Matthew began a period of rapid intensification; during a 24-hour period beginning at 00:00 UTC on September 30, the cyclone's maximum winds more than doubled, from 80 mph (130 km/h) to 165 mph (270 km/h), making Matthew a Category 5 hurricane,[71] the first since Hurricane Felix in 2007.[72] Due to upwelling of cooler waters, Matthew weakened to a Category 4 hurricane later on October 1. Matthew remained a powerful Category 4 hurricane for several days, making landfall near Les Anglais, Haiti, around 11:00 UTC on October 4 with winds of 150 mph (240 km/h). Continuing northward, the cyclone struck Maisí in Cuba early on October 5. Cuba's and Haiti's mountainous terrain weakened Matthew to Category 3 status, as it began to accelerate northwestwards through the Bahamas.[71]

Restrengthening occurred as Matthew's circulation became better organized, with the storm becoming a Category 4 hurricane again while passing Freeport. However, Matthew began to weaken again as an eyewall replacement cycle took place. The storm significantly weakened while closely paralleling the coasts of Florida and Georgia, with the northwestern portion of the outer eyewall coming ashore in Florida while the system was a Category 2 hurricane. Matthew weakened to a Category 3 hurricane late on October 7 and then to a Category 1 hurricane by 12:00 UTC on October 8. About three hours later, the hurricane made landfall at Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge, near McClellanville, South Carolina, with winds of 85 mph (140 km/h).[71] Convection became displaced as Matthew pulled away from land, with NHC declaring the system an extratropical cyclone about 200 mi (320 km) east of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, on October 9.[73] Matthew's remnants persisted for another day, before being absorbed by a cold front on October 10.[71]

Heavy rains and strong winds buffeted the Lesser Antilles. The winds caused widespread power outages and damaged crops, particularly in St. Lucia, while flooding and landslides caused by the rainfall damaged many homes and roads. One person died in St. Vincent when he was crushed by a boulder.[74] The storm brought precipitation to Colombia's Guajira Peninsula, which saw its first heavy rain event in three years. One person drowned in a river in Uribia.[75] In Haiti, flooding and high winds disrupted telecommunications and destroyed extensive swaths of land; around 80% of Jérémie sustained significant damage.Jérémie,[76] Matthew left about $1.9 billion in damage and at least 546 deaths.[71][77] Heavy rainfall spread eastward across the Dominican Republic, where four were killed.[78] Effects in Cuba were most severe along the coast, where storm surge caused extensive damage.[79] Four people were killed due to a bridge collapse,[80] and total losses in the country amounted to $2.58 billion, most of which occurred in the Guantánamo Province.[81] Passing through the Bahamas as a major hurricane, Matthew inflicted severe impacts across several islands, particularly Grand Bahama, where an estimated 95% of homes sustained damage in the townships of Eight Mile Rock and Holmes Rock. In Florida, much of the damage occurred was caused by strong winds and storm surge in the east-central and northeastern portions of the state. About 1 million people lost power. Damage in Florida reached over $2.75 billion and there were 12 deaths. About 478,000 lost electricity in Georgia and South Carolina. Torrential rain caused severe flooding, especially in North Carolina, where some rivers exceed record heights set by Hurricane Floyd. About 100,000 structures were flooded and damage reached $1.5 billion. Overall, Matthew caused at least 603 deaths and about $15.1 billion in damage.

- Note: Matthew was Storm of the Year for 2016.

Hurricane Harvey (2017)

[edit]| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 13, 2017 – September 3, 2017 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min); 938 mbar (hPa) |

The NHC began monitoring an area of low pressure southwest of Cape Verde on August 13, which was expected to merge with a tropical wave that just emerged off the coast of Africa, within a few days.[82] Instead the two systems remained separate,[83] with the first low pressure area coalescing into a potential tropical cyclone by 15:00 UTC on August 17.[84] A reconnaissance aircraft investigating the system was able to locate a well-defined circulation, and the disturbance was upgraded to Tropical Storm Harvey accordingly, six hours later.[85] On a westward course into the Caribbean Sea, the storm was plagued by relentless wind shear, and it degenerated to an open tropical wave south of Hispaniola, by 03:00 UTC on August 20.[86] Harvey's remnants continued into the Bay of Campeche, where more conducive environmental conditions led to the re-designation of a tropical depression, around 15:00 UTC on August 23, and subsequent intensification into a tropical storm by 04:00 UTC on the next morning.[87][88] The cyclone began a period of rapid intensification shortly thereafter, attaining hurricane intensity by 17:00 UTC on August 24,[89] Category 3 strength around 19:00 UTC on August 25,[90] and Category 4 intensity by 23:00 UTC on that day.[89] Harvey crossed the shore between Port Aransas and Port O'Connor, Texas around 03:00 UTC on August 26, possessing maximum winds of 130 mph (215 km/h).[91] The storm gradually spun down, becoming a tropical storm around 18:00 UTC on August 26, as it meandered across southeastern Texas.[92]

Rockport, Fulton, and the surrounding cities bore the brunt of Harvey's eyewall as it moved ashore in Texas. Numerous structures were heavily damaged or destroyed, boats were tossed or capsized, power poles were leant or snapped, and trees were downed. As debris covered roadways and cellphone service was compromised, communication to the hardest-hit locales was severed. One person was killed in Rockport after a fire began in his home, and approximately a dozen people were injured.[93] Farther northeast, dire predictions of potentially catastrophic flooding came to fruition in Houston and nearby locales, where floodwaters submerged interstates, forced residents to their attics and roofs, and overwhelmed emergency lines. The National Weather Service tweeted, "This event is unprecedented & all impacts are unknown & beyond anything experienced..." At least 30 people were killed in the Houston area due to flooding.[94] In addition to the flooding, Harvey spawned several tornadoes around Houston.[95] A preliminary report calculated a total of $198.63 billion (2017 USD) in damages due to Harvey, making Hurricane Harvey the costliest tropical cyclone on record, surpassing Hurricane Katrina, and the second-costliest natural disaster worldwide.[96] Harvey killed 91 people, including 1 in Guyana[97] and 90 in the United States.[98] The storm produced 64.58 in (1,640 mm) of rainfall in Texas, the highest-ever rainfall total for any tropical cyclone in the United States and the third-highest rainfall total for a tropical cyclone in the Atlantic basin.[99][nb 1]

Harvey is the first major hurricane to strike the United States since Hurricane Wilma in 2005, ending the record-long drought that lasted 4,323 days.[100] It is the most intense tropical cyclone to move ashore the mainland since Hurricane Charley in 2004, the first Category 4 hurricane to make landfall in Texas since Hurricane Carla in 1961, and the wettest hurricane ever to strike the continental United States.[101]

- Note: Harvey was one of 3 Storms of the Year for 2017.

Hurricane Irma (2017)

[edit]| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 22, 2017 – September 16, 2017 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 180 mph (285 km/h) (1-min); 914 mbar (hPa) |

The NHC began monitoring a tropical wave over western Africa on August 26.[102] The disturbance entered the Atlantic late the next day,[103] gradually organizing into Tropical Storm Irma west of Cabo Verde around 15:00 UTC on August 30.[104] Early on August 31, Irma underwent a remarkable period of rapid intensification, with winds increasing from 70 mph (110 km/h) – a high-end tropical storm – to 115 mph (185 km/h), a major hurricane, in a mere 12 hours.[105] An eyewall replacement cycle then took place shortly thereafter, which caused the storm to fluctuate between Category 2 and 3 intensity. [106] Irma resumed intensifying on September 4, and was upgraded into a Category 4 hurricane by 21:00 UTC. At that time, hurricane warnings were issued for the Leeward Islands. By 11:45 UTC the following day, Irma had become a Category 5 hurricane with 175 mph (280 km/h) winds. Six hours later, its winds further increased to 185 mph (295 km/h), tying Irma with the 1935 Labor Day hurricane, Hurricane Gilbert of 1988, and Hurricane Wilma of 2005 for the second-strongest Atlantic hurricane by wind speed, surpassed only by Hurricane Allen of 1980.

In the aftermath of Irma, development on the islands of Barbuda and Saint Martin was described as being "95% destroyed" by respective political leaders, with 1,400 people feared homeless in Barbuda.[107] So far, Irma has resulted in at least 132 deaths, including 44 across the Caribbean, and 88 in the United States.[108][109][110]

Hurricane Irma was also the top Google searched term in the US and globally, in the year 2017.[111]

- Note: Irma was one of 3 Storms of the Year for 2017.

Hurricane Maria (2017)

[edit]| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 13, 2017 – October 3, 2017 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 175 mph (280 km/h) (1-min); 908 mbar (hPa) |

On September 13, the NHC began monitoring a tropical wave southwest of Cabo Verde.[112] The disturbance moved west, organizing into a potential tropical cyclone at 15:00 UTC on September 16 and Tropical Storm Maria six hours later.[113][114] On a west-northwest course, Maria intensified at an exceptional rate and attained Category 5 strength around 23:45 UTC on September 18.[115] After striking Dominica at that intensity a little over an hour later,[116] the storm weakened slightly as it entered the eastern Caribbean Sea; amid favorable conditions, however, Maria regained Category 5 intensity and eventually reached peak winds of 175 mph (280 km/h) late on September 19.[117] Around 08:00 UTC on September 20, the eyewall of Maria struck Vieques,[118] and a little over two hours later, the core of the storm made landfall near Yabucoa, Puerto Rico, with winds of 155 mph (250 km/h).[119] Land interaction caused a significant degration in Maria's structure, and it weakened to a Category 2 hurricane while moving offshore.[120] Growing in size and curving north, Maria regained Category 3 strength and maintained this intensity for several days before entering a less conducive environment.[121] After fluctuating between tropical storm and minimal hurricane strength off the coastline of North Carolina,[122] the system turned sharply east away from the United States and ultimately transitioned into an extratropical cyclone over the far northern Atlantic on September 30.[123][124]

Dominica sustained catastrophic damage from Maria, with nearly every structure on the island damaged or destroyed.[125] Surrounding islands were also dealt a devastating blow, with reports of flooding, downed trees, and damaged buildings. Puerto Rico also suffered catastrophic damage. The island's electric grid was devastated, leaving all 3.4 million residents without power. Many structures were leveled, while floodwaters trapped thousands of citizens. The United States National Guard, Coast Guard, Army Corps of Engineers, and other like units worked to administer aid and assist in search and rescue operations. However, the U.S. federal government response was criticized for its delay in waiving the Jones Act, a statute which prevented Puerto Rico from receiving aid on ships from non-U.S. flagged vessels. Along the coastline of the United States, tropical storm-force gusts cut power to hundreds of citizens; rip currents offshore led to three deaths and numerous water rescues. Estimates of damage from Maria were pegged at $91.61 billion (2017 USD), mainly in Puerto Rico. Hurricane Maria killed at least 3,057 people, with 2,975 killed in Puerto Rico, 65 in Dominica, 5 in the Dominican Republic, 2 in Guadeloupe, 3 in Haiti, 3 in the United States Virgin Islands, and 4 in the Contiguous United States.[126]

- Note: Maria was one of 3 Storms of the Year for 2017.

Super Typhoon Jebi (Maymay)

[edit]| Violent typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 5 super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 25, 2018 – September 9, 2018 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 195 km/h (120 mph) (10-min); 915 hPa (mbar) |

A low-pressure system formed near the Marshall Islands on early August 25, 2018, developing and being upgraded to a tropical depression on August 27 by the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA). There was a persistent deep convection in the system which lead to the upgrade to a tropical storm by the JMA and was given the name Jebi. On August 29, the storm abruptly underwent rapid intensification and became the third super typhoon and the second category 5 of the season. On September 4, a weakened but still powerful Jebi made landfall over the southern part of Tokushima Prefecture at around 12:00 JST (03:00 UTC) before moving over Osaka Bay and making another landfall at around Kobe, Hyōgo Prefecture at around 14:00 JST (05:00 UTC). Osaka was hit badly with a maximum wind gust of 209 km/h recorded at Kansai International Airport and 171 km/h at Osaka city's weather station, where the minimum sea level pressure (962 mb) was the lowest since 1961's record of 937 mb (Typhoon Nancy) and the fifth lowest on record. A 3.29 metre storm surge led to flooding along the Osaka Bay, including Kansai International Airport, where the runways were flooded and some airport facilities were damaged by wind and water. Osaka's iconic Universal Studios Japan was also closed during the event of the typhoon. Wakayama also recorded a maximum wind gust of 207 km/h. Jebi then moved over Kyoto which wrecked more havoc. Multiple shrines were closed during the duration of the typhoon. Kyoto Station received a lot of damage, the glass above the atrium covering the central exit, shops and hotel, collapsed, narrowly missing a few by centimeters. The typhoon ultimately emerged into the Sea of Japan shortly after 15:00 JST (06:00 UTC). Simultaneously, a cold front formed southwest of the typhoon, initiating the beginning of an extratropical transition on September 4. On September 5, after JTWC issued a final warning at 00:00 JST (15:00 UTC), Jebi was downgraded to a severe tropical storm at 03:00 JST (18:00 UTC) when it was located near the Shakotan Peninsula of Hokkaido. The storm completely transitioned into a storm-force extratropical cyclone off the coast of Primorsky Krai, Russia shortly before 10:00 VLAT (09:00 JST, 00:00 UTC). Later, the extratropical cyclone moved inland. The terrain of Khabarovsk Krai contributed to the steadily weakening trend as the system moved inland northwestward and then northward; extratropical low passed northeast of Ayan early on September 7. Jebi's extratropical remnant continued northward and then turned northeastward, before dissipating early on September 9, over the Arctic Ocean.

Jebi was the strongest storm to hit Japan since Typhoon Yancy of 1993. In total, Jebi killed 17 people and inflicted over US$13 billion in insured losses, making Jebi the costliest typhoon to strike Japan, in terms of insured losses. 11 deaths were reported from Japan and 6 deaths were reported from Taiwan. Despite the extensive amount of damage caused by the storm, the name Jebi was not retired.

Hurricane Florence (2018)

[edit]| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 28, 2018 – September 19, 2018 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-min); 937 mbar (hPa) |

On August 28, 2018, the NHC first mentioned the possibility of tropical cyclone formation from a tropical wave expected to exit western Africa.[127] Two days later, the tropical wave moved off the coast of Senegal, with disorganized thunderstorms[128] and a well-defined low-pressure area.[129] Due to the system's threat to the Cape Verde islands, the NHC initiated advisories on Potential Tropical Cyclone Six at 15:00 UTC on August 30.[130] The system organized into Tropical Depression Six at 21:00 UTC on August 31.[131] Early on September 1, Tropical Depression Six strengthened into Tropical Storm Florence. Gradual intensification occurred as Florence continued west-northwestward across the central Atlantic, and at 15:00 UTC on September 4, it intensified into the third hurricane of the season.[132] On September 5, Florence unexpectedly underwent rapid intensification into a Category 3 major hurricane.[133] Rapid intensification continued and at 21:00 UTC, Florence intensified into a Category 4 hurricane at 22°24′N 46°12′W / 22.4°N 46.2°W,[134] farther northeast than any previous Category 4 hurricane in the Atlantic during the satellite era.[135] However, rapid intensification caused the now-stronger storm to veer northwards into a zone of greater vertical wind shear.[136] Over the next 30 hours, Florence rapidly weakened into a tropical storm due to the strong wind shear, with the storm's cloud pattern becoming distorted.[137] After entering a zone of less shear and crossing into warmer waters, Florence restrengthened into a hurricane on September 9.[138] On the next day, Florence underwent a second period of rapid intensification and reintensified into a major hurricane.[139] At 16:00 UTC on the same day, Florence reintensified into a Category 4 hurricane.[140] Florence continued strengthening into the next day, reaching its peak intensity at 18:00 UTC on September 11, with 1-minute sustained winds of 150 mph (240 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 937 millibars (27.7 inHg).[141] Before impacting the coast however, Florence underwent an eyewall replacement cycle and encountered moderate wind shear, weakening it to a Category 2 hurricane.[142] Florence quickly weakened into a tropical depression inland, and the NHC issued its last advisory at 10:00 UTC on September 16, passing on responsibility to the Weather Prediction Center (WPC). At that point, Florence had also begun to gradually accelerate westward.[143] On September 17, Florence slowly turned to the northeast, while continuing to weaken. Late on the same day, Florence weakened into a remnant low, while situated over West Virginia.[144] Florence still posed a threat inland, as it dumped tremendous amounts of rain on the Eastern Seaboard. The system finally dissipated in the open Atlantic on September 19, when the system's remnants were absorbed into a developing extratropical storm.[145][146] This system later led to the formation of the long-lived Hurricane Leslie.[147][148]

Florence posed a major threat to the East Coast of the United States, especially North Carolina and South Carolina, which declared states of emergency, along with Virginia, Maryland,[149] and Washington, D.C.[150] The NHC issued its first hurricane watches at 9:00 UTC on September 11.[151]

Hurricane Michael (2018)

[edit]| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 1, 2018 – October 16, 2018 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 160 mph (260 km/h) (1-min); 919 mbar (hPa) |

On October 1, a broad area of low pressure formed over the southwestern Caribbean Sea, absorbing the remnants of Tropical Storm Kirk by the next day.[152] On October 2, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) began monitoring the system for tropical development.[153] While strong upper-level winds initially inhibited development, the disturbance gradually became better organized as it drifted generally northward and then eastward toward the Yucatán Peninsula. On October 6, the NHC deemed the system an imminent threat to land, and thus initiated advisories on Potential Tropical Cyclone Fourteen.[154][155] Early on the next morning, the system organized into a tropical depression, before intensifying into Tropical Storm Michael several hours later.[152] Michael quickly became a hurricane around midday on October 8 as a result of rapid intensification.[152] At 21:00 UTC on October 9, while approaching the Gulf Coast, Michael strengthened into a major hurricane, making it the second major hurricane of the season.[152] Michael continued rapidly intensifying the following day, and at 17:30 UTC on October 10, Michael made landfall at its peak intensity, as a low-end Category 5 hurricane with sustained winds of 160 mph (260 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 919 millibars (27.1 inHg), becoming the strongest storm of the season and also the third-strongest landfalling hurricane in the U.S. on record in terms of central pressure.[152][156] This also made Michael the first Category 5 hurricane to make landfall in the United States since Hurricane Andrew in 1992, and one of only 4 storms known to make landfall at that intensity in the mainland United States in recorded history. At that time, however, Michael was operationally classified as a high-end Category 4 hurricane, prior to the NHC's post-season analysis of data gathered from the storm.[152][157] After crossing through the southeastern United States, Michael started restrengthening early on October 12, as a result of baroclinic forcing while transitioning into an extratropical cyclone.[152]

The combined effects of the precursor low to Michael and a disturbance over the Pacific Ocean caused significant flooding across Central America.[158] Nearly 2,000 homes in Nicaragua suffered damage and 1,115 people evacuated. A total of 253 and 180 homes were damaged in El Salvador and Honduras, respectively.[158] More than 22,700 people were directly affected throughout the three countries.[159] Catastrophic damage occurred in Mexico Beach, Florida, where the storm made landfall at peak intensity.[160] Michael killed at least 60 people; at least 15 fatalities occurred across Central America: 8 in Honduras,[161] 4 in Nicaragua, and 3 in El Salvador.[158][159] In the United States, at least 57 were killed across Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Virginia, mostly in the state of Florida.[162][163][164] Michael caused at least $25 billion (2018 USD) in property damage in the U.S.,[165] along with an additional $100 million (2018 USD) in damages in Central America.[166]

On March 20, 2019, at the 41st session of the RA IV hurricane committee, the World Meteorological Organization retired the name Michael from its rotating name lists, due to the extreme damage and loss of life it caused along its track, particularly in the Florida Panhandle and southwest Georgia, and its name will never again be used for another Atlantic hurricane. It will be replaced with Milton for the 2024 season.[167]

- Note: Michael was Storm of the Year for 2018.

Typhoon Yutu (2018)

[edit]| Violent typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 5 super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 21, 2018 – November 3, 2018 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 215 km/h (130 mph) (10-min); 900 hPa (mbar) |

Early on October 21, 2018, a tropical depression developed to the east of Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands, with the JMA initiating advisories on the system. Shortly afterward, the JTWC assigned the storm the identifier 31W. The system began to strengthen, becoming a tropical storm several hours later, and the JMA named the system Yutu. Favorable conditions, including low wind shear and high ocean-surface temperatures, allowed Yutu to explosively intensify on the following day, with the storm reaching severe tropical storm strength and then typhoon intensity a few hours later. From October 23 to 24, Yutu continued to organize and explosively intensify, reaching Category 5 super typhoon intensity on October 24. The typhoon continued to strengthen and displayed a healthy convective structure, while moving towards the island of Saipan. Later on the same day, Typhoon Yutu made landfall on the island of Tinian while at peak intensity, just south of Saipan, at Category 5 intensity, with 1-minute sustained winds of 285 km/h (180 mph), becoming the most powerful storm on record to impact the northern Mariana Islands.[168][169]

After making landfall in Saipan, Yutu underwent an eyewall replacement cycle, which it successfully completed on the next day, and the storm strengthened back to Category 5 super typhoon status on October 26, at 15:00 UTC.

On October 27, Yutu's eye became cloud-filled, indicative of weakening, and the storm weakened to a Category 4 super typhoon. On the same day, the storm entered PAGASA's area of responsibility, and Yutu was given the name Rosita by PAGASA. On October 28, Yutu quickly weakened, as ocean sea-surface heat content significantly declined.

After making landfall on October 30, Yutu rapidly weakened, and when it emerged over the South China Sea, low ocean heat content and westerly wind shear caused Yutu to weaken below typhoon status. On November 2, Yutu weakened into a remnant low off the coast of China, before dissipating early on the next day.

On October 25, in Saipan, the typhoon killed a woman when it wrecked the building she was staying in, and injured 133 other people, three of whom were severely injured. On Saipan and nearby Tinian, high winds from Yutu knocked down more than 200 power poles. Most of the buildings in southern Saipan lost their roofs or were destroyed, including a high school that was wrecked.[170]

Intense Tropical Cyclone Idai (2019)

[edit]| Intense tropical cyclone (MFR) | |

| Category 4 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | March 4, 2019 – March 21, 2019 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 195 km/h (120 mph) (10-min); 940 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 11 formed off the east coast of Mozambique on March 4, 2019. Afterward, the tropical depression drifted northeastward very slowly, making landfall on Mozambique later that day. On March 6, Tropical Depression 11 was given a yellow tropical cyclone development warning by the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC). On March 7, the storm turned west-southwestward, while continuing to retain its tropical identity overland. On March 8, Tropical Depression 11 weakened and turned back towards the east. Early on March 9, the tropical depression emerged into the Mozambique Channel and began to organize. On the same day, the JTWC stated that the system had a high probability for genesis into a tropical cyclone, and later on the same day, the system strengthened into a moderate tropical storm and received the name Idai. On March 10, Idai began to rapidly intensify, strengthening into a tropical cyclone near Madagascar, and the system made yet another turn westward, moving to the southwest. On the next day, the storm intensified into the seventh intense tropical cyclone of the season, and soon reached its peak intensity as a Category 4-equivalent tropical cyclone. On March 12, Idai began to weaken, as the system underwent an eyewall replacement cycle. On March 13, Idai began accelerating westward. At 00:00 UTC on March 15, the MFR reported that Idai had made landfall near Beira, Mozambique, with 10-minute sustained winds of 165 km/h (105 mph).[171] Idai quickly weakened after landfall, degenerating into a tropical depression later that day. Afterward, Idai slowly moved inland while dumping large amounts of rain, resulting in flash flooding. Late on March 16, Idai degenerated into a remnant low, but the storm's remnant continued dumping rain across the region. On March 17, Idai's remnant turned eastward once again, eventually re-emerging into the Mozambique Channel a second time on March 19. On March 21, Idai's remnants dissipated.[172][173]

As a tropical depression, Idai affected Malawi and Mozambique, during its first landfall. At least 56 people died, and 577 others were injured due to flooding in Malawi. About 83,000 people were displaced. The southern districts of Chikwawa and Nsanje became isolated by floodwaters.[174] In Mozambique, 66 people were killed by the flooding, and affected 141,000 people. The Council of Ministers required 1.1 billion metical (US$17.6 million) to help those who were affected by the flooding.[175] In total, Idai killed at least 1,303 people and left thousands more missing, becoming one of the deadliest tropical cyclones in the modern history of Africa and the Southern Hemisphere as a whole.[176][177][178][55] With this death toll, Idai is the deadliest tropical cyclone recorded in the South-West Indian Ocean basin, and the second-deadliest tropical cyclone overall in the Southern Hemisphere, behind only Cyclone Flores in 1973.[179] In addition, the total damages from the cyclone are expected to exceed US$2.2 billion (2019 USD), which would make Idai the costliest cyclone on record in the basin.[180][181]

Hurricane Dorian (2019)

[edit]| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 19, 2019 – September 9, 2019 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 185 mph (295 km/h) (1-min); 910 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave exited the west coast of Africa on August 19 and organized as it moved westward, becoming a tropical depression early on August 24 approximately 805 mi (1,295 km) east-southeast of Barbados. The depression quickly developed curved banding features and intensified into Tropical Storm Dorian later that day while heading west-northwestward. Dry air prevented any significant further intensification and organization for several days. Early on August 27, Dorian struck Barbados as a very compact cyclone with winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) and then passed over Saint Lucia later that day. The mountainous terrain of Saint Lucia disrupted the storm's circulation, though a new circulation formed farther to the north. Dorian resumed organizing while moving northeastward over the Caribbean, with a partial eyewall and inner core developing by August 28. The cyclone reached hurricane intensity at 15:30 UTC on August 28 while striking the eastern tip of Saint Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands; another landfall occurred on Saint Thomas a few hours later. After emerging into the Atlantic on August 28, Dorian eventually began moving west-northwestward due to an upper-level low moving to the south and a subtropical ridge expanding westward.[182]

Encountering very warm water temperatures, ample moisture, and low wind shear, Dorian began rapidly intensifying on August 30, reaching major hurricane intensity around 18:00 UTC that day. Strengthening further, the cyclone became a Category 5 hurricane at 12:00 UTC on September 1, a few hours prior to making landfall on Elbow Cay in the Abaco Islands with winds of 185 mph (295 km/h); Dorian became the strongest tropical cyclone on record to strike the Bahamas. A weakening high pressure area to the north and collapsing steering currents caused Dorian to move very slowly. The cyclone struck Grand Bahama early on September 2 while still a Category 5 hurricane, and the storm stalled just north of Grand Bahama for about a day.[183][184] The storm weakened due to land interaction and upwelling, falling below major hurricane late on September 3. An eastward-moving, large mid-level trough forced Dorian to move north-northwestward and then northward, causing it to remain offshore Florida. The cyclone re-strengthened into a Category 3 hurricane over the Gulf Stream on September 5, but weakened back to a Category 2 later that day. Dorian then curved northeastward and scraped the Outer Banks of North Carolina on September 6 before moving ashore at Cape Hatteras with winds of 100 mph (155 km/h). Embedded within the mid-latitude flow, the cyclone accelerated northeastward and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone late on September 7. The remnant extratropical storm struck Nova Scotia and later Newfoundland, before being absorbed by another extratropical cyclone on September 9.[182]

Throughout the Windward Islands, the storm produced wind gusts up to 61 mph (98 km/h), observed on Martinique. Approximately 4,000 homes lost electricity and many streets became impassable due to flooding.[185] Mostly minor damage occurred in Barbados.[186] Some areas of the U. S. Virgin Islands reported hurricane-force winds, with Buck Island observing sustained winds of 82 mph (132 km/h).[182] Winds from Dorian left island-wide blackouts on Saint Thomas and Saint John, while 25,000 customers lost power on Saint Croix.[187][188] In the British Virgin Islands, the storm caused flood and wind damage in the outskirts of Road Town.[189] One death occurred in Puerto Rico during preparations for the storm.[190] Gusty winds left roughly 23,000 households without electricity across the island.[187] Dorian inflicted catastrophic damage in some regions of the Bahamas. Approximately 87 percent of the damage nationwide occurred in the Abaco Islands, where the storm struck at peak intensity and generated winds of at least tropical storm-force for more than three days. Around 75 percent of homes there were damaged to some degree.[182] Further, Dorian damaged about 90 percent of infrastructure in Marsh Harbour and obliterated shanty-type homes in the town.[191][192] Grand Bahama also experienced extreme impacts,[182] with storm surge submerging at least 60 percent of the island. The hurricane severely damaged or destroyed around 300 homes on the island. Throughout the Bahamas, an estimated 13,000 homes suffered severe damage or were completely destroyed,[193] while at least 70,000 people were left homeless.[194] Dorian killed at least 70 people and caused at least $3.4 billion in damage, making it the costliest hurricane in the country's history.[182]

Over 160,000 electrical customers in Florida lost power during the storm.[195] Dorian caused coastal flooding in some areas, especially in immediate oceanfront or riverfront sections of St. Augustine and Jacksonville.[196] Six deaths occurred in the state.[197] Strong winds in South Carolina downed numerous trees and power lines,[182] leaving more than 270,000 residences and workplaces without power.[198] Coastal flooding and flash flooding impacted the Charleston and Georgetown areas. Three tornadoes in Horry County also caused damage.[199] The eastern portions of the state experienced storm surge ranging from 4 to 7 ft (1.2 to 2.1 m), wind gusts up to 110 mph (180 km/h), rainfall totals between 5 and 10 in (130 and 250 mm),[200] and 25 tornadoes.[201] Dare County was particularly hard hit, with 1,126 structures damaged.[202] The storm also destroyed 20-25 percent of the state's tobacco crop.[203] Three deaths were reported in North Carolina.[204] Gusty winds and beach erosion occurred in other states along the East Coast, especially in Delaware and New Jersey. Damage in the United States totaled roughly $1.6 billion.[182] In Canada, the extratropical remnants of Dorian left about 412,000 customers without power in Nova Scotia and another 80,000 in New Brunswick, with the former representing approximately 80 percent of the province.[205] The storm damaged homes, buildings, and boats, as well as downed trees, across Canadian Maritimes, though the worst impacts occurred in Halifax, Moncton, and much of Prince Edward Island. Insured damage alone reached $78.9 million.[206] Dorian caused at least $5.07 billion (2019 USD) in damages, and the storm likely killed at least 329 people, as 245 residents of the Bahamas still remain missing as of July 2020.

- Note: Dorian was Storm of the Year for 2019.

Super Typhoon Hagibis (2019)

[edit]| Violent typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 5 super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 2, 2019 – October 22, 2019 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 195 km/h (120 mph) (10-min); 915 hPa (mbar) |

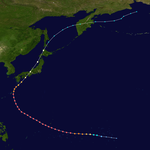

Hagibis developed from a tropical disturbance located a couple hundred miles north of the Marshall Islands on October 2, 2019. The Joint Typhoon Warning Center issued a red tropical cyclone formation alert - noting that the disturbance could undergo rapid intensification upon being identified as a tropical depression. On the next day, October 3, both the Japan Meteorological Agency and the Joint Typhoon Warning Center began issuing advisories on Tropical Depression 20W. The depression stayed at the same intensity as it travelled west toward the Mariana Islands on October 4, but on October 5, 20W began undergoing rapid intensification and early that day, the system was issued with the name "Hagibis" by the JMA, which means speed in Filipino. Sea surface temperatures and wind shear became extremely favourable for tropical cyclogenesis and Hagibis started extremely rapid intensification on October 6, and became a Category 5 super typhoon in under 12 hours - the second of the 2019 Pacific typhoon season. Edging closer to the uninhabited areas of the Mariana Islands, Hagibis displayed excellent convection as well as a well-defined circulation. The system developed a pinhole eye and made landfall on the Northern Mariana Islands at peak intensity, with 10-minute sustained winds of 195 km/h (120 mph) and a central pressure of 915 hPa (27.02 inHg).[207]

Land interaction did not affect Hagibis much, but as the system continued to move westward, it underwent an eyewall replacement cycle, which is usual for all tropical cyclones of a similar intensity. The inner eyewall was robbed of its needed moisture and Hagibis began to weaken, but it formed a large and cloud-filled eye, which then became clear, and Hagibis reached its second peak. Travelling toward Japan, Hagibis encountered high vertical wind shear and its inner eyewall began to degrade, and the outer eyewalls rapidly eroded as its center began to be exposed. On October 12, Hagibis made landfall on Japan at 19:00 p.m JST (10:00 UTC) on the Izu Peninsula near Shizuoka. Then, an hour later at 20:00 p.m. JST, (11:00 UTC), Hagibis made its second landfall on Japan in the Greater Tokyo Area. Wind shear was now at 60 knots (69 mph; 111 km/h), and Hagibis' structure became torn apart as it sped at 34 knots (39 mph; 63 km/h) north-northeast toward more hostile conditions. On October 13, Hagibis became an extratropical low and the JMA and JTWC issued their final advisories on the system. However, the extratropical remnant of Hagibis persistent for more than a week, before dissipating on October 22. Hagibis caused catastrophic destruction across much of eastern Japan. Hagibis spawned a large tornado on October 12, which struck the Ichihara area of Chiba Prefecture during the onset of Hagibis,; the tornado, along with a 5.7 magnitude earthquake off the coast, caused additional damage those areas that were damaged by Hagibis.[208][209] Hagibis caused $15 billion (2019 USD) in damages, making it the costliest typhoon on record.[210]

Super Cyclonic Storm Amphan (2020)

[edit]| Super cyclonic storm (IMD) | |

| Category 5 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 16, 2020 – May 20, 2020 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 240 km/h (150 mph) (3-min); 920 hPa (mbar) |

At 00:00 UTC on May 16, 2020, a depression formed in the southeast Bay of Bengal and was identified as BOB 01. Six hours later, the India Meteorological Department (IMD) upgraded the system to a deep depression. The system began bringing torrential rainfall to Sri Lanka and Southern India. Around 15:00 UTC, the system further developed into Cyclonic Storm Amphan.[211][212] That morning, landslide and flooding warnings were hoisted for parts of eastern Sri Lanka and the Indian state of Kerala were given expectations of torrential rainfall in the coming days.[213] By 09:00 UTC on May 17, Amphan had intensified into a very severe cyclonic storm. Within 12 hours, the storm had developed an eye and started to rapidly intensify, becoming an extremely severe cyclonic storm. According to the JTWC, it explosively intensified from a Category 1-equivalent cyclone to a Category 4-equivalent cyclone in just 6 hours. The following morning around 10:30 UTC, the IMD upgraded Amphan to a super cyclonic storm with 3-minute sustained winds of 240 km/h (150 mph) and a minimum pressure of 920 hectopascals (27.17 inHg). This marked the second year in a row featuring a super cyclonic storm, the previous year seeing Kyarr in the Arabian Sea. On May 20, at approximately 17:30 IST, the cyclone made landfall near Bakkhali, West Bengal after weakening subsequently. It rapidly weakened once inland, and dissipated on the next day. Amphan killed a total of 128 people and left behind a trail of catastrophic damage, causing $13.7 billion (2020 USD) in damages, making the cyclone the costliest storm ever recorded in the basin.

Wintry Hell

[edit]Winer Storm Jonas (2016)

[edit]| Duration | January 19–29, 2016 |

|---|---|

| Lowest pressure | 983 mb (29.03 inHg) |

| Maximum snow | 42 in (110 cm) |

| Fatalities | 55 fatalities |

| Damage | $500 million – $3 billion (2016 USD) |

The development of the winter storm was anticipated by forecasters for at least a week.[214] It originated in a shortwave trough—a weather disturbance in the upper atmosphere—that came ashore at the Pacific Northwest on January 19.[215] The trough strengthened as it moved southeastward through the Great Plains,[216] and on January 21 it spawned a weak low-pressure area over central Texas.[217] The incipient storm system began to intensify as it tracked eastward through the Gulf Coast states, triggering a line of strong to severe thunderstorms and multiple tornado warnings.[218]

During the mid-afternoon hours of January 22, a new low-pressure area began to develop over the coast of the Carolinas, as the former storm tracked into central Georgia. Owing to uncertainty in short-range guidance but a high confidence of a sharp northern edge of precipitation, many forecasts were predicting 12" of snow or less until just hours before snowfall began, from Allentown, Pennsylvania, toward New York City and the southern coast of New England. As the storm moved further north and rapidly strengthened, it became apparent that snowfall would be much higher farther north, and forecasters quickly began upgrading their totals.[219] Early on January 24, as the storm was leaving New England, the system began to become elongated, as a secondary low developed to the southwest of the storm's central low.[220] On January 25, the blizzard left the East Coast of the United States; on the same day, the system was named Karin by the University of Berlin.[221]

Accompanied by a strong jet stream in the Atlantic, the remnants of the storm crossed the British Isles on January 26. The wind and rain associated with the low was forecast to have the potential to cause disruption in the United Kingdom,[222] and indeed there were areas that saw severe weather.[223] During the next few days, the system accelerated towards the northeast. On January 29, the storm system was absorbed by Windstorm Leone, over Finland.[224]

The storm was given various unofficial names, including Winter Storm Jonas, Blizzard of 2016, and Snowzilla among others. The highest reported snowfall was 40 inches (100 cm) in Glengary, West Virginia. Locations in five states exceeded 30 inches of snow. The storm dropped 18 inches of snow in Washington, D.C., 22 inches in Philadelphia, 26 inches in Baltimore, 30.5 inches in New York City.[225][226][227] States of emergency were declared in Maryland, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, West Virginia, Virginia, Delaware, New York, and Washington, D.C.[228] The storm also caused coastal flooding in Delaware and New Jersey. Cape May, New Jersey set a record high water level at 8.98 feet, higher than the 8.90 feet seen during Hurricane Sandy.[225] High winds led to blizzard conditions in many areas. Sustained winds of 59 miles per hour (95 km/h) with gust of 72 mph were recorded in Delaware. 70 miles per hour (110 km/h) gusts were also recorded in Massachusetts.[225]

Winter Storm Uri (2021)

[edit]| Duration | February 13–17, 2021 |

|---|---|

| Lowest pressure | 960 mb (28.35 inHg) |

| Maximum snow | 26 in (66 cm) |

| Fatalities | ≥ 302 fatalities |

| Damage | ≥ $196.5 billion (2021 USD) |

On February 13, a frontal storm developed off the coast of the Pacific Northwest and moved ashore, before moving southeastward, with the storm becoming disorganized in the process.[229][230] During this time, the storm reached a minimum pressure of 992 millibars (29.3 inHg) over the Rocky Mountains.[230] On the same day, The Weather Channel gave the storm the unofficial name Winter Storm Uri, due to the expected impacts from the storm;[231] the Federal Communications Commission later adopted the name in their reports after February 17.[232] From February 12 to 13, a trough dipped southward from Northern California into northern Mexico, which channeled moisture from Texas towards the storm, as the system moved southeastward.[233] Over the next couple of days, the storm began to develop as it entered the Southern United States and moved into Texas.[234] From February 13 to 14, a second, much larger trough developed over Central United States, aided by a southward shift from the polar vortex, while the winter storm moved into Texas. The trough became fully developed by February 15, channeling significant amounts of moisture into the winter storm and also contributing to a historic cold wave that affected most of the Central and Eastern United States.[233] Winds in the jet stream reached 170 mph (275 km/h) around the trough.[233] On February 15, the system developed a new surface low off the coast of the Florida Panhandle, as the storm turned northeastward and expanded in size.[235]

On February 16, the storm developed another low-pressure center to the north as the system grew more organized, while moving towards the northeast.[236][233] Later that day, the storm broke in half, with the newer storm moving northward into Quebec, while the original system moved off the East Coast of the U.S.[237] By the time the winter storm exited the U.S. late on February 16, the combined snowfall from the multiple winter storms within the past month had left nearly 75% of the contiguous United States covered by snow, which was the largest amount of snow cover seen in the United States since early 2003.[238][233] On February 17, the storm's secondary low dissipated as the system approached landfall on Newfoundland, intensifying in the process.[239] At 12:00 UTC that day, the storm's central pressure reached 985 millibars (29.1 inHg), as the center of the storm moved over Newfoundland.[240] On the same day, the storm was given the name Belrem by the Free University of Berlin.[241] The storm continued to strengthen as it moved across the North Atlantic, with the storm's central pressure dropping to 960 millibars (28 inHg) by February 19.[242][243] On February 20, the storm developed a second-low pressure area and gradually began to weaken, as it moved northwestward towards Iceland.[244][245] Afterward, the storm turned westward and moved across southern Greenland on February 22, weakening even further as it did so.[246] The storm then stalled south of Greenland, while continuing to weaken, before dissipating on February 24.[247][248]

The storm resulted in over 170 million Americans being placed under various winter weather alerts being issued by the National Weather Service in the United States across the country and caused blackouts for over 9.9 million people in the U.S. and Mexico, most notably the 2021 Texas power crisis.[249][250][251] The blackouts were the largest in the U.S. since the Northeast blackout of 2003.[252] The storm contributed to a severe cold wave that affected most of North America. The storm also brought severe destructive weather to Southeastern United States, including several tornadoes. On February 16, there were at least 20 direct fatalities and 13 indirect fatalities attributed to the storm;[253][254][255][256][231] by July 14, the death toll had risen to at least 302, including 288 people in the United States and 14 people in Mexico.[257][258][255][259][256] The damages from the blackouts are estimated to be at least $196.5 billion (2021 USD), making the system the costliest winter storm on record.[260][261] It is also the deadliest winter storm in North America since the 1993 Storm of the Century, which killed 318 people.[262]

Record-Breakers

[edit]Super Typhoon Nancy (1961)

[edit]| Category 5 super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 7, 1961 – September 17, 1961 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 345 km/h (215 mph) (1-min); 882 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Storm Nancy, having developed on September 7, 1961, in the open West Pacific, rapidly intensified to reach super typhoon status early on the 9th. Nancy continued to strengthen, and reached peak winds of 215 mph (187 knots) on the 12th. Such intensity is speculative, as Reconnaissance Aircraft was in its infancy and most intensities were estimates. Furthermore, later analysis indicated that equipment likely overestimated Nancy's wind speed; if the measurements were correct, Nancy would have had the highest wind speeds of any tropical cyclone by 25 mph. Nancy held this record unofficially until October 2015, when Hurricane Patricia surpassed the storm in both intensity and peak sustained winds. Regardless, Nancy was a formidable typhoon, and retained super typhoon status until the 14th as it neared Okinawa. The typhoon turned to the northeast, and made landfall on southern Japan on the 16th with winds of 100 mph. It continued rapidly northeastward, and became extratropical on the 17th in the Sea of Okhotsk. Well executed warnings lessened Nancy's potential major impact, but the typhoon still caused 172 fatalities and widespread damage.

Super Typhoon Tip (Warling)

[edit]| Violent typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 5 super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 1, 1979 – October 24, 1979 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 260 km/h (160 mph) (10-min); 870 hPa (mbar) |