Typhoon Phanfone (2014)

Typhoon Phanfone at peak strength after an eyewall replacement cycle on October 3 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | September 28, 2014 |

| Post-tropical | October 6, 2014 |

| Dissipated | October 12, 2014 |

| Very strong typhoon | |

| 10-minute sustained (JMA) | |

| Highest winds | 175 km/h (110 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 935 hPa (mbar); 27.61 inHg |

| Category 4-equivalent super typhoon | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/JTWC) | |

| Highest winds | 250 km/h (155 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 922 hPa (mbar); 27.23 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 11 total |

| Damage | $100 million (2014 USD) |

| Areas affected | Mariana Islands, Japan, Alaska |

| IBTrACS | |

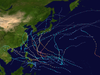

Part of the 2014 Pacific typhoon season | |

Typhoon Phanfone, known in the Philippines as Typhoon Neneng, was a powerful tropical cyclone which affected Japan in early October 2014.[1] It was the eighteenth named storm and the eighth typhoon of the 2014 Pacific typhoon season. Phanfone started as a large area of convection well west of the International Date Line. The system was well organized and classified as Tropical Depression 18W on September 29. At the same day, it gained the name Phanfone due to very favorable conditions and intense thunderstorms rich with convection surrounding the storm's center. Phanfone would later go rapid intensification on October 1 due to warm sea-surface temperatures and very favorable environments. JTWC upgraded Phanfone to a Category 4 typhoon but weakened later back to Category 3 due to its eye replacing the old one and undergoing a minor eyewall replacement cycle.

Phanfone later entered the PAR, assigning the name Neneng. It left several hours later, maintaining its Category 3 strength. On October 4, Phanfone reached its peak intensity as a Category 4 super typhoon before steadily weakening. The typhoon later made landfall at Hamamatsu, Japan at the time of its extratropical transition. The system later moved over Southwestern Alaska and dissipated on October 12.

Meteorological history

[edit]

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

Early on September 29, the JTWC upgraded the system to a tropical storm, shortly before the JMA also upgraded it to a tropical storm and named it Phanfone.[2][3] Tracking along the southern periphery of the subtropical ridge, the storm intensified very slowly for two days, although conditions remained favorable. Late on September 30, the JMA upgraded Phanfone to a severe tropical storm, right before the JTWC upgraded it to a typhoon.[4][5] After the JMA also upgraded Phanfone to a typhoon at noon on October 1, the system started to deepen more rapidly when tracking along the southwestern periphery of a deep-layered subtropical ridge.[6] Under low vertical wind shear and good dual channel outflow enhanced by the mid-latitude westerlies to the north, Phanfone formed a pinhole eye early on October 2.[7] According to the JMA, Phanfone reached peak intensity with ten-minute maximum sustained winds at 175 km/h (110 mph) at 06:00 UTC, and it also became equivalent to the category 4 strength on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale.[8][9] Soon, the eye became cloud-filled and formed a secondary eyewall, suggesting an eyewall replacement cycle.[10]

The PAGASA named the typhoon Neneng when it entered the Philippine Area of Responsibility early on October 3.[11] In addition, Phanfone formed a ragged and large eye, indicating the completion of the eyewall replacement cycle.[12] Early on October 4, the JTWC upgraded Phanfone to a super typhoon when it was located about 170 km (105 mi) east-southeast of Minamidaitōjima. As the system started to tap into the mid-latitude westerlies, it was in an area of strong vertical wind shear offset by vigorous outflow, namely the improved poleward channel.[13] Only six hours later, the JTWC downgraded Phanfone back to a typhoon owing to the loosening spiral banding.[14] At noon, the JMA analysed that Phanfone started to weaken.[15] The convective tops of the system intermittently warmed up afterwards, but the ragged and large eye still maintained well.[16] Phanfone sharply recurved and accelerated northeastward early on the next day, tracking along the western edge of the deep-layered subtropical ridge.[17]

Typhoon Phanfone passed near the southern coast of Kii Peninsula around 03:00 JST on October 6 (18:00 UTC on October 5).[18] The eye immediately dissipated, as well as the system started to undergo extratropical transition right before making landfall near Hamamatsu of the Shizuoka Prefecture in Japan after 08:00 JST (23:00 UTC on October 5).[19] The JTWC issued the final warning to Phanfone early on October 6, and the system completely became extratropical at noon.[20][21] The storm stopped weakening and began to deepen again early on October 7, and it crossed the International Date Line as a powerful extratropical cyclone early the next day.[22] Post-Tropical Cyclone Phanfone, which was located about 890 km (555 mi) southwest of Unalaska, Alaska, reached peak intensity of its extratropical period at noon on October 8, with a barometric pressure of 948 hPa (27.99 inHg) and hurricane-force winds.[23] The system started to weaken again early on October 9, and it turned northward early on October 11.[24][25] The system eventually moved inland over Southcentral Alaska early on October 12 and dissipated later that day.[26][27]

Preparations and impact

[edit]The extratropical remnant of Phanfone brought locally strong winds to portions of the Alaskan Peninsula from October 12–13. Gusts peaked at 119 km/h (74 mph) in King Cove.[28] Moisture associated with Phanfone later fueled a separate cyclone over the Gulf of Alaska which brought heavy rains to parts of British Columbia, Canada.[29]

Mariana Islands

[edit]On September 29, the National Weather Service office in Guam issued a tropical storm watch for Saipan, Tinian, and the Northern Mariana Islands in anticipation of Phanfone's arrival the following day. This was subsequently upgraded to a tropical storm warning and accompanied by a small craft advisory and a flash flood watch.[30] A typhoon watch was also raised for Alamagan and Pagan that evening.[31] At 10:40 a.m. local time (00:40 UTC) Northern Mariana Islands Governor Eloy Inos declared a level one Tropical Cyclone Condition of Readiness. All non-essential government employees were sent home shortly thereafter. Public and private schools suspended classes on September 30 and October 1 while Northern Marianas College closed only for September 30.[32] Six public shelters were opened at schools across Saipan; however, no one utilized them.[33] An "all clear" was issued for Saipan and Tinian after the storm's passage during the evening of September 30 and for the remainder of the Mariana Islands the following day.[32][33]

Japan

[edit]

Phanfone started affecting Japan late on October 4, as it began weakening. High waves and winds of 90 mph (150 km/h) were reported most in southern Japan.[34] At the Kadena Air Base, the typhoon killed a U.S. airman and left two others missing after they were swept out to sea.[35] It was also reported that 10 people were injured and nearly 10,000 houses were without power.[36] On October 5, Phanfone also affected the Formula One 2014 Japanese Grand Prix, bringing strong winds and heavy rainfall which made the track surface wet and significantly reduced visibility. Because of this, the race had to be red flagged twice; the first time because the torrential rain made conditions too treacherous to race in and the second time because of a fatal accident involving Jules Bianchi, which was partially caused by the wet track conditions.[37][38]

In Japan, a total of eleven people were killed by the typhoon, with several others missing or injured.[39]

Heavy rains from the typhoon worsened the spread of radioactive materials in groundwater around the Fukushima I and Fukushima II nuclear power plants, which suffered nuclear meltdowns in 2011 following a MW9.0 earthquake and subsequent tsunami. Levels of the radioactive hydrogen isotope tritium soared ten-fold from the previous month to 150,000 becquerels per liter. Strontium-90, a substance known to cause bone cancer, rose to a record 1.2 million becquerels per liter. A separate sampling site showed a doubling in the levels of a beta particle-emitting substance from prior to the typhoon.[40]

Throughout Shizuoka Prefecture, 8 buildings were destroyed and a further 1,439 buildings were damaged by flooding. Losses in the prefecture amounted to ¥3.21 billion (US$29.5 million).[41] Agricultural damage in Japan was calculated at ¥7.7 billion (US$70.7 million),[42] while total economic losses nationwide were estimated at ¥10.5 billion (US$100 million) by Aon Benfield.[43]

See also

[edit]- Weather of 2014

- Tropical cyclones in 2014

- Other tropical cyclones named Phanfone

- Other tropical cyclones named Neneng

- Typhoon Melor (2009)

- Typhoon Jelawat (2012)

- Typhoon Wipha (2013)

- Typhoon Vongfong (2014)

- Typhoon Chaba (2016)

- Typhoon Lan (2017)

- Typhoon Trami (2018)

References

[edit]- ^ "台風第18号による大雨と暴風 平成26年10月4日~10月6日". www.data.jma.go.jp (in Japanese). 気象庁 . Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- ^ "Tropical Storm 18W (Eighteen) Warning Nr 002". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ^ "RSMC Tropical Cyclone Advisory 290600". Japan Meteorological Agency. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ^ "RSMC Tropical Cyclone Advisory 301800". Japan Meteorological Agency. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ^ "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 18W (Phanfone) Warning Nr 10". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ^ "RSMC Tropical Cyclone Advisory 011200". Japan Meteorological Agency. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ^ "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 18W (Phanfone) Warning Nr 14". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ^ "Track file of Super Typhoon 18W (Phanfone)" (TXT). U.S. Naval Research Laboratory. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ^ "RSMC Tropical Cyclone Advisory 020600". Japan Meteorological Agency. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 18W (Phanfone) Warning Nr 16". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ "TTT Typhoon Warning 01". PAGASA. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 18W (Phanfone) Warning Nr 18". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ "Prognostic Reasoning for Super Typhoon 18W (Phanfone) Warning Nr 22". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 18W (Phanfone) Warning Nr 23". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ "RSMC Tropical Cyclone Advisory 041200". Japan Meteorological Agency. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 18W (Phanfone) Warning Nr 25". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 18W (Phanfone) Warning Nr 27". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ 台風第 18 号による大雨と暴風 (PDF) (in Japanese). Japan Meteorological Agency. October 8, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ "Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 18W (Phanfone) Warning Nr 30". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ "Tropical Storm 18W (Phanfone) Warning Nr 031". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived from the original on October 1, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ "RSMC Tropical Cyclone Advisory 061200". Japan Meteorological Agency. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ "Marine Weather Warning for GMDSS Metarea XI 2014-10-07T18:00:00Z". WIS Portal – GISC Tokyo. Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ "High Seas Forecast for METAREA XII 1745 UTC Wed Oct 08 2014". Ocean Prediction Center. Archived from the original on October 29, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ "High Seas Forecast for METAREA XII 1145 UTC Thu Oct 09 2014". Ocean Prediction Center. Archived from the original on October 29, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ "High Seas Forecast for METAREA XII 1630 UTC Sat Oct 11 2014". Ocean Prediction Center. Archived from the original on October 29, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ "Pacific Surface Analysis valid at 00:00 UTC on 12 October 2014". Ocean Prediction Center. October 12, 2014. Archived from the original (GIF) on October 29, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ "Pacific Surface Analysis valid at 06:00 UTC on 12 October 2014". Ocean Prediction Center. October 12, 2014. Archived from the original (GIF) on October 29, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ National Weather Service Office in Anchorage, Alaska (2015). "Alaska Event Report: High Wind". National Climatic Data Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- ^ "Heavy rainfall warning issued: typhoon remnants to pummel Metro Vancouver all week". Vancity Buzz. October 13, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- ^ Dave Ornauer (October 6, 2014). "Pacific Storm Tracker: Typhoon 18W (Phanfone)". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- ^ "Tropical storm condition 3 for Saipan and Tinian". Marianas Variety. September 29, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- ^ a b Andrew O. De Guzman and Richelle Agpoon-Cabang (September 30, 2014). "All clear for Saipan, Tinian". Marianas Variety. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- ^ a b Richelle Agpoon-Cabang (October 1, 2014). "Public school classes resume today; no families used shelters". Marianas Variety. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- ^ "Typhoon Phanfone: Tokyo in Direct Path, All-Time Wind Record Threatened; Strong Winds Reported Near Osaka (FORECAST)". October 5, 2014.

- ^ "One U.S. airman killed, two missing after Typhoon Phanfone slams Okinawa". CBS News. October 5, 2014.

- ^ "Deadly Typhoon Phanfone heads out of Tokyo". BBC News. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ "F1 driver Jules Bianchi suffers 'severe head injury' in Japanese GP crash". CNN. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ DiZinno, Tony (18 July 2015). "Jules Bianchi dies at age 25, his family confirms". NBC Sports. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ "Typhoon Vongfong heads towards Japan's main islands, 23 people injured". ABC News. October 12, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ^ "Tritium up tenfold in Fukushima groundwater after Typhoon Phanfone". The Japan Times. October 12, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- ^ <台風18号>河川・道路174カ所被害 静岡県まとめ. 静岡新聞 (in Japanese). Yahoo! News. October 11, 2014. Archived from the original on October 18, 2014. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ 平成26年台風第18号による被害状況等について (in Japanese). Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. April 10, 2015. Retrieved May 8, 2015.

- ^ Global Catastrophe Recap: October 2014 (PDF) (Report). Aon Benfield. November 5, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

External links

[edit]- JMA General Information of Typhoon Phanfone (1418) from Digital Typhoon

- JMA Best Track Data of Typhoon Phanfone (1418) (in Japanese)