Topi

| Topi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Queen Elizabeth National Park, Uganda | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Alcelaphinae |

| Genus: | Damaliscus |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | D. l. jimela

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Damaliscus lunatus jimela (Matschie, 1892)

| |

| |

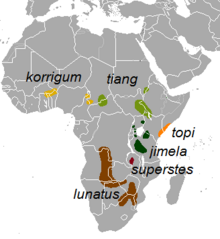

| Range in dark green | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Damaliscus lunatus jimela is a subspecies of topi,[3] and is usually just called a topi.[4] It is a highly social and fast type of antelope found in the savannas, semi-deserts, and floodplains of sub-Saharan Africa.

Names

[edit]The word tope or topi is Swahili, and was first recorded in the 1880s by the German explorer Gustav Fischer to refer to the local topi population in the Lamu County region of Kenya; this population is now designated as Damaliscus lunatus topi.[5] Contemporaneously, in English, sportsmen referred to the animal as a Senegal hartebeest, as it was considered the same species as what is now recognised as D. lunatus korrigum.[6][7][8]

Other names recorded in East Africa by various German explorers were mhili in Kisukuma and jimäla in Kinyamwezi. The Luganda name was simäla according to Neumann, or nemira according to Lugard.[5]

By the turn of the 19th century this antelope was called a topi by most in English.[6][7][8] Writing in 1908, Richard Lydekker complains that it would have so much simpler if all these new forms of korrigum had simply been called East African korrigum, Bahr-el-Ghazal korrigum, etc., than constantly adopting different native names for different geographic forms of essentially the same antelope.[7]

In 2003 Fenton Cotterill argued the correct name for jimela topi was nyamera in English,[9] referencing that to the 1993 Kingdon field guide, which reports it as another Swahili name for topi antelopes.[10]

New names invented in 2011 for various populations of this subspecies were Serengeti topi, Ruaha topi and Uganda topi.[2]

Taxonomy and range

[edit]Damaliscus lunatus jimela was originally described in 1892 by the German zoologist Paul Matschie based on the skull of an animal shot by the famous German hunter Richard Böhm in what is now Tanzania, and a watercolour painting Böhm had made of the animal, which his widow had given to Matschie.[5][11] By the turn of the century this had become the accepted scientific name for topi in East Africa, but in 1907 a new subspecies was introduced by Lydekker to classify the topi occurring in Kenya and Uganda: D. korrigum selousi based on a specimen from the Uasin-Gishu plateau. It was distinguished from the other races by having the black face mask not cover the eyes and muzzle completely; these being surrounded by patches of tan-coloured hair.[7][11]

In 1914 Gilbert Blaine pointed out that Matschie's description in which the dark patch on the upper foreleg extended as a stripe down the front of the leg towards the hooves, if correctly taken from Böhm's painting, and if correctly painted, was not present in any of the specimens known to him in London, and that this was thus another subspecies than the other topi of East Africa, and perhaps restricted to a small area. He subsequently created another four subspecies based on small differences in hair colour and size, recognising seven in East Africa.[11]

Some recent authors have controversially[12][13][14] split it into three different species,[2] or have classified it as Damaliscus korrigum jimela,[15][16] although this has been rejected by the American Society of Mammalogists' Mammal Diversity Database as of 2021.[2] Some recent researchers simply consider this population to belong to D. lunatus korrigum.[17]

In 1910, the Spanish professor Ángel Cabrera described a new species, Damaliscus phalius, also from the Uasin-Gishu plateau, on account of the face mask, normally dark-coloured, being whitish, like a bontebok. This taxon was described from a skull and a photograph of the slain animal, procured by the sportsman Ricardo de la Huerta, who described to the professor a great herd of this species, and that he saw it in two locations. The natives also assured him that the Teddy Roosevelt hunting party had also already come across the same herd.[18] If this was indeed the case, when in 1914 in the United States his book on the matter was published, he explained that such a whitish face was a mere variation, seen uncommonly among a herd of otherwise normal topi. Upon examining a set of thirty specimens from the wider region in the American collection, he described how a number of them had some varying amount of whitish hairs, albeit not across the entire face.[8]

According to the 2005 definition of D. korrigum jimela, topi can be found in the following countries: Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda. The species is regionally extinct in Burundi.[16] The 2011 definition of D. jimela restricted it to the Serengeti subpopulation. D. ugandae occurred in Uganda and the Lake Rukwa population was considered D. eurus. It is unclear what the small intervening populations were supposed to be.[2] Data given in the same 2011 book which recognised all these species show that D. jimela, D. ugandae, D. eurus and D. topi are all morphologically indistinguishable, aside from a single characteristic used to recognise these species: the subjective hair colour of a limited number of skins.[19]

Description

[edit]The hair colour of the pelage may vary across the different geographic subpopulations, being darker or lighter (see photos).[19]

This subspecies has horns with a shape that gives the effect of the space between them having a lyrate profile when seen from a certain angle, as opposed to lunate, which is seen in the sassaby subspecies found to the south: D. lunatus lunatus and D. lunatus superstes.[15] It is in principle indistinguishable from D. lunatus topi, the topi population found to the east along the coasts.[19] A hartebeest also has lyrate horns, but these are sharper angled.[20]

-

female with calf, Uganda

-

in the Serengeti

-

grazing in the Masai Mara

-

running in Uganda

-

A pair of topi

-

Topi in Kenya

Ecology

[edit]Topi prefer pastures with green grass that is medium in height with leaf-like swards. Topis are more densely populated in areas where green plants last into the dry season, particularly near water.[21] When foraging for food, topi tend to take small bites at a fast rate.[22]

The topi has what is possibly the most diverse social organization of the antelopes. The reproductive organization ranges between the traditional territorial system or resource defense polygyny herds to gatherings that contain short-lasting territories to lek systems. In patches of grassland surrounded by woodlands, topi live in the sedentary-dispersion mode.[23]

The vast majority of births occur between October and December with half of them occurring in October.[24] The fidelity of a female to a territory can last three years in the Serengeti.[23] The females in these territories function as part of the resident male's harem. These herds tend to be closed (except when new females are accepted) and both the male and his females defend the territory.[25]

Status and conservation

[edit]In 1998, Rod East estimated a global population of ca. 71,000 topi for the IUCN.[26] The conservation status of D. lunatus jimela was assessed as "least concern" by the IUCN in 2008, based on an estimated population of ca. 93,000, with over 90% in protected areas, and a lack of evidence to show an overall decline of over 20% over three generations (20 years) that would justify "near threatened" or "vulnerable" status. Nonetheless they stated that they believed the population was trending downward.[4]

In Tanzania, East estimated a total of 58,510 individuals in 1998.[26] According to the 2014 A Field Guide to the Larger Mammals of Tanzania, there were a total of 35,000-46,500 individuals in the country. Of those, there are some 27,000-38,500 in the Serengeti, an estimated 4,000-5,000 in the adjoining Moyowosi and Kigosi Game Reserves, and 1,000-2,000 in Ugalla River Game Reserve.[27]

In Kenya there were an average total of 126,330 topi in the period 1977–1980, based on aerial survey data.[17] East estimated a total of 11,120 individuals in 1998,[26] although aerial counts at the time registered at least three times more. A 2011 study by Ogutu et al. of the wild animal population in and around Masai Mara National Park found that topi population size had declined by over 70% between the 1977–1979 average population and the 2007–2009 average population.[28][29] A 2016 study by Ogutu et al. compiling aerial survey records for entire Kenya found an average population of 22,239 for the period 2011–2013. There was an increase of topi numbers in Narok County since the late 1970s, but this was more than offset by the drops in other counties.[17]

In Rwanda, East estimated a that there were less than 500 individuals in 1998.[26] An aerial census counted 560 in Akagera National Park and neighbouring Mutara Domaine de Chasse (hunting area) in 2013, an identically done census counted 805 in 2015. This was believed to be natural increase in the absence of significant numbers of predators.[30]

In Uganda the first topi population counts in the Ishasha Flats region in the Rukungiri District, a part of Queen Elizabeth National Park, where the topi seemed to congregate, were calculated from monthly ground count samples from 1963-1967, but these were soon doubted as the methodology used caused an overestimation due to the spatial distribution of the antelopes in aggregations. Based on three ground-based counts in 1970, Jewell estimated a total of 4,000 topi in this area using a different calculation method.[31] The mean population derived from estimations based on aerial surveys made in 1971 and 1972 was 4,932.[32] Yoaciel counted a maximum of 5,578 in 1975, but in 1977 the numbers declined to half that, with the last count of 1978 jumping back to 2,973. At the same time, the home range of the population shrank and kob numbers doubled.[31] In 1981 a conservationist claimed that the Yoaciel et al. study revealed topi numbers here were 20% of their 1973 level in 1980,[33] although that appears to be a incorrect. To explain the population reduction, Yoaciel et al. pointed to three causes: poaching pressure, lion predation and changes in the vegetation structure. Poaching had increased, especially with the establishment of a military border post in Ishasha. Lions in Ishasha had a preference for topi, in some years the topi formed over 80% of their prey, meaning the 32 adult lions roughly killed some 660 topi in those years, although lower percentages of topi prey in later years meant lions killed 320 a year. Lastly, the rangeland was changing in vegetation structure, with the tree species Acacia sieberiana encroaching upon the shrinking grassland. It was suspected either changed fire regimes and the local reduction in the elephant population due to ivory poaching was causing this afforestation.[31] East estimated a that there were 580 individuals in 1998 in Uganda, with an unknown number in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).[26] Joint aerial surveys of the adjoining Queen Elizabeth National Park, Kigezi Game Reserve and Kyambura Game Reserve in Uganda, and Parc National des Virunga (Virunga National Park) in the DRC, which together completely encircle Lake Edward, found that all of the topi cluster to the south of the lake shore in the Ishasha Flats. The total minimum population in this region was counted as 2,874 in the 2006 survey, but dropped to 1,302 in the 2010 survey.[34][35] Another joint survey in 2014 found 2,679 topi in the region, most in the Uganda part.[36] In 2020, Uganda Wildlife Authority executive director Samuel John Mwandha stated that the wildlife in park has been increasing in the last five years.[37]

In the adjoining Pian-Upe, Bokora and Matheniko Game Reserves, and the controlled hunting areas surrounding and connecting these areas to Kidepo Valley National Park, topi were numerous in the 1960s.[38][39] A ground-based survey in April 2012 registered no sightings of topi, it is possible they have been extirpated. The Uganda Wildlife Authority was planning to relocate twenty topi to the area as of 2013.[40]

Lake Mburo National Park also supports a topi population. Annual roadside survey count numbers have fluctuated, with a low of 57 in 1995, and a high of 362 only two years later. The 2010 survey counted 173 topi.[41] Topi also occur in the controlled hunting areas buffering the park.[42] A problem facing topi in the park are the changes in habitat occurring over time. Most areas which were formerly grassland in the park have changed into bushveld or forest as the invasive native shrubby tree species Acacia hockii has colonised these areas. The acacia in turn is protecting other bush and tree species, which are growing faster and thicker. This afforestation is forcing topi into the surrounding ranches and private land, causing topi to be resented as pests. Uganda has tried to organise these areas into controlled hunting areas for sport, but land owners complain the money this generates is being spent on community projects such as schools, health centres and roads rather than addressing individual challenges resulting from problem animals. The procurement of an excavator for habitat management, different wildfire regimes, translocating excess animals, fencing, wildlife ranching for the hunting industry, community tourism, licensing more sport hunting companies and increasing quotas may alleviate this; the local community is permitted to uproot acacia for firewood, but this has proved ineffective.[41]

In 2016 the IUCN estimated a similar number as in 1998, with 50,000-70,000 mature individuals, and continued to state the population was trending downward. No mention made of the 2008 assessment, but it was stated that East had estimated 58,500 in 1998 (the assessment cites the date 1999) in Tanzania and the 2014 book had estimated it as 35,000-46,500, which represents a 25-46% decline over three generations (18 years) in the country which holds the majority of the population, thus assuming the figures for Tanzania are accurate and can be applied to other countries, and assuming East's 1998 numbers for the other countries are accurate, this could mean the world population had dropped by a mean of 36%, which would qualify this species for a "vulnerable" status, although if the population in Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda had not fallen below their 1998 estimations the species would actually qualify as "near threatened".[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2 August 2016). "Damaliscus lunatus ssp. jimela". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T6241A50185829. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T6241A50185829.en.

- ^ a b c d e "Damaliscus lunatus (Burchell, 1824)". ASM Mammal Diversity Database. American Society of Mammalogists. 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2016). "Damaliscus lunatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T6235A50185422. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T6235A50185422.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ a b IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (30 June 2008). "Damaliscus lunatus ssp. jimela". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008: e.T6241A12591307. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T6241A12591307.en.

- ^ a b c Matschie, Paul (1895). Die Säugthiere Deutsch-Ost-Afrikas (in German). Berlin: Dietrich Reimer. pp. 111–112. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.14826. OCLC 12266224.

- ^ a b Sclater, Philip Lutley; Thomas, Oldfield; Wolf, Joseph (January 1895). The Book of Antelopes. Vol. 1. London: R.H. Porter. pp. 67–71. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.65969. OCLC 1236807.

- ^ a b c d Lydekker, Richard (1908). The game animals of Africa. London: R. Ward, limited. pp. 116–121. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.21674. OCLC 5266086.

- ^ a b c Roosevelt, Theodore; Heller, Edmund (1914). Life-histories of African game animals. Vol. 1. New York: C. Scribner's Sons. pp. 351–358. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.14851. OCLC 1598642.

- ^ Cotterill, Fenton Peter David (January 2003). "A biogeographic review of tsessebe antelopes, Damaliscus lunatus (Bovidae: Alcelaphini) in south-central Africa". Durban Museum Novitates. 28: 45–55. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ Kingdon, Jonathan (23 April 2015). The Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. pp. 428–431. ISBN 978-1-4729-2135-2.

- ^ a b c Blaine, Gilbert (1914). "Notes on the Korrigum, with a Description of Four new Races". The Annals and Magazine of Natural History; Zoology, Botany, and Geology. 8 (13): 326–335. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ "About the Mammal Diversity Database". ASM Mammal Diversity Database. American Society of Mammalogists. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ Holbrook, Luke Thomas (June 2013). "Taxonomy Interrupted". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 20 (2): 153–154. doi:10.1007/s10914-012-9206-1. S2CID 17640424. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ Gutiérrez, Eliécer E.; Garbino, Guilherme Siniciato Terra (March 2018). "Species delimitation based on diagnosis and monophyly, and its importance for advancing mammalian taxonomy". Zoological Research. 39 (3): 301–308. doi:10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2018.037. PMC 6102684. PMID 29551763. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ a b Cotterill, Fenton Peter David (January 2003). "Insights into the taxonomy of tsessebe antelopes, Damaliscus lunatus (Bovidae: Alcelaphini) in south-central Africa: with the description of a new evolutionary species". Durban Museum Novitates. 28: 11–30. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ a b Grubb, P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-8221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c Ogutu, Joseph O.; Piepho, Hans-Peter; Said, Mohamed Y.; Ojwang, Gordon O.; Njino, Lucy W.; Kifugo, Shem C.; Wargute, Patrick W. (27 September 2016). "Extreme Wildlife Declines and Concurrent Increase in Livestock Numbers in Kenya: What Are the Causes?". PLOS ONE. 11 (9): e0163249. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1163249O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0163249. PMC 5039022. PMID 27676077.

- ^ Cabrera, Ángel (14 June 1910). "On a new Antelope and on the Spanish Chamois". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 1910 (4): 998–999. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1910.tb01925.x. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ a b c Heller, Rasmus; Frandsen, Peter; Lorenzen, Eline Deirdre; Siegismund, Hans R. (September 2014). "Is Diagnosability an Indicator of Speciation? Response to "Why One Century of Phenetics Is Enough"". Systematic Biology. 63 (5): 833–837. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syu034. hdl:10400.7/567. PMID 24831669.

- ^ Estes, R. D. (1991). The Behavior Guide to African Mammals, Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, Primates. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. pp. 142–146. ISBN 978-0-520-08085-0.

- ^ Vesey-FitzGerald, DF (1955). "The Topi Herd". Oryx. 3: 4–8. doi:10.1017/S0030605300037972.

- ^ Murray, M. G.; D. Brown (1993). "Niche separation of grazing ungulates in the Serengeti: an experimental test" (PDF). Journal of Animal Ecology. 62 (2): 380–389. Bibcode:1993JAnEc..62..380M. doi:10.2307/5369. JSTOR 5369.

- ^ a b Duncan, P. (1976). "Ecological studies of topi antelope in the Serengeti". Wildlife News. 11 (1): 2–5.

- ^ Sinclaire, A. R. E.; Mduma, Simon A.R.; Arcese, M. (2000). "What Determines Phenology and Sychrony of Ungulate Breeding in Serengeti?". Ecology. 81 (8): 2100–2111. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2000)081[2100:WDPASO]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Duncan, P. (1975). Topi and their food supply. Ph.D. thesis, University of Nairobi.

- ^ a b c d e East, Rod; IUCN/SSC Antelope Specialist Group (1998). "African Antelope Database" (PDF). Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission. 21: 200–207. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ Foley, C.; Foley, L.; Lobora, A.; de Luca, D.; Msuha, M.; Davenport, T. R. B.; Durant, S. (2014). A Field Guide to the Larger Mammals of Tanzania. Princeton, USA: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Ogutu, Joseph O.; Owen-Smith, Norman; Piepho, Hans-Peter; Said, Mohammed Yahya (2011). "Continuing wildlife population declines and range contraction in the Mara region of Kenya during 1977-2009". Journal of Zoology. 285 (2): 99–109. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2011.00818.x.

- ^ Ogutu, Joseph; Owen-Smith, Norman; Piepho, Hans-Peter; Said, Mohammed (June 2011). "ILRI Policy Brief 2 - Wildlife numbers in Kenya's Mara region in decline" (PDF) (Press release). International Livestock Research Institute. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ "Akagera National Park Aerial Census Report Summary-August 2015" (PDF). African Parks. 14 October 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ a b c Yoaciel, S. M.; van Orsdol, K. G. (March 1981). "The influence of environmental changes on an isolated topi (Damaliscus lunatus jimela Matschie) population in the Ishasha Sector of Rwenzori National Park, Uganda". African Journal of Ecology. 19 (1–2): 167–174. Bibcode:1981AfJEc..19..167Y. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1981.tb00660.x. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ Eltringham, S. K.; Din, Naila (1977). "Estimates of population size of some ungulate species in the Rwenzori National Park, Uganda". East African Wildlife Journal. 15 (4): 305–316. Bibcode:1977AfJEc..15..305E. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1977.tb00412.x.

- ^ Malpas, Robert (May 1981). "Elephant Losses in Uganda – and Some Gains". Oryx. 16 (1): 41–44. doi:10.1017/S0030605300016720.

- ^ A. Plumptre; D. Kujirakwinja; D. Moyer; M. Driciru; A. Rwetsiba (August 2010). Greater Virunga Landscape Large Mammal Surveys, 2010 (Report). Wildlife Conservation Society. pp. 5, 6. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ Uganda Wildlife Authority: Planning Unit (26 July 2012). Buhanga, Edgar; Namara, Justine (eds.). Queen Elizabeth National Park, Kyambura Wildlife Reserve, Kigezi Wildlife Reserve-General Management Plan (2011 - 2021) (Report). Uganda Wildlife Authority. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ F. Wanyama; E. Balole; P. Elkan; S. Mendiguetti; S. Ayebare; F. Kisame; P. Shamavu; R. Kato; D. Okiring; S. Loware; J. Wathaut; B.Tumonakiese; Damien Mashagiro; T. Barendse; A.J.Plumptre (October 2014). Aerial surveys of the Greater Virunga Landscape - Technical Report 2014 (Report). Wildlife Conservation Society. p. 11. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ "Queen Elizabeth National park records an increase in wildlife". The Independent (Uganda). Kampala, Uganda. 4 July 2020. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ Tumushabe, Godber W.; Bainomugisha, Arthur (2004). "ACODE Policy Briefing Paper No. 7, 2004-The Politics of Investment and Land Acquisition in Uganda-A Case Study of Pian Upe Game Reserve" (PDF) (Press release). Advocates Coalition for Development and Environment. p. 3. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ "Bokora Wildlife Reserve". Uganda Wildlife Authority. 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ Uganda Wildlife Authority: Conservation Department and Karimojong Overland Safaris (28 May 2013). Pian-Upe Wildlife Reserve-General Management Plan (PDF) (Report). Uganda Wildlife Authority. pp. 20–22, 24. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ a b Uganda Wildlife Authority: Planning Unit (25 February 2015). Buhanga, Edgar; Namara, Justine (eds.). Lake Mburo Conservation Area - General Management Plan (2015 - 2025) (PDF) (Report). Uganda Wildlife Authority. pp. 7, 11, 20, 22, 27, 35, 36, 38, 39. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ "Uganda Safari – Nile buffalo, Sitatunga, Reedbuck, Topi, Kob and plains game". Worldwide Trophy Adventures. 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2021.