Damaliscus lunatus

| Topi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Tsessebe in Botswana | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Alcelaphinae |

| Genus: | Damaliscus |

| Species: | D. lunatus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Damaliscus lunatus (Burchell, 1824)

| |

| |

| Damaliscus lunatus | |

Damaliscus lunatus is a large African antelope of the genus Damaliscus and subfamily Alcelaphinae in the family Bovidae, with a number of recognised geographic subspecies.[2] Some authorities have split the different populations of the species into different species,[3][4] although this is seen as controversial.[5][6][7] Common names include topi,[1][8][9] sassaby (formerly also sassayby),[10] tiang and tsessebe.[9]

Etymology

[edit]The word tope or topi is Swahili, and was first recorded by the German explorer Gustav Fischer on the ancient city island of Lamu off the Kenyan coast. Other names recorded in East Africa by various German explorers were mhili in Kisukuma and jimäla in Kinyamwezi. The Luganda name was simäla according to Neumann, or nemira according to Lugard.[11]

Taxonomy

[edit]The first thing published about this antelope was the afore-mentioned painting of a young male sassayby by Daniell from 1820, but the first scientific description was by William John Burchell in 1824. In 1812 hunters attached to Burchell's expedition shot a female animal in what is now Free State, in what is thought to be the southernmost part of its range. Burchell named it the "crescent-horned antelope", Antilope lunata. Burchell had the horns and frontlet sent to London, this is now the type specimen. Charles Hamilton Smith was the first to equate the sassayby with Antilope lunata in the 1827 section on ruminants in the English translation of George Cuvier's Le Règne Animal.[10][12]

An 1822–1824 British expedition across the Sahara to the ancient kingdom of Bornu,[13] returned with single set of horns of an antelope known in the language of that land as a korrigum. In 1836 these horns were classified as a new species.[14]

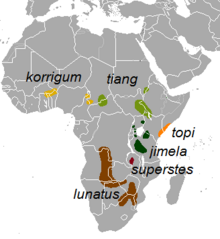

Until the early 2000s the generally accepted taxonomic interpretation of the different geographic populations of topi antelopes was that of Ansell in 1972, who recognised five subspecies. In 2003 Fenton Cotterill published a paper advocating splitting the southern, nominate subspecies into two independent species under something he invented called the 'Recognition Species Concept', and regarding the northern four subspecies as a different, provisional species (Damaliscus korrigum).[4] In the 2005 Mammal Species of the World Grubb accepted Cotterill's interpretation in full, splitting the topi into three species: a southern, northern and Cotterill's new Bangweulu species (D. superstes).[3] In 2006 Macdonald considered the topi to be a single species with six subspecies, subsuming the Bangweulu (see map).[15] The IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group followed this interpretation in 2008.[16] In the 2011 book Ungulate Taxonomy, Colin Groves and Grubb went even further and split the topi into nine species.[17] They used what they called the "diagnostic phylogenetic species concept" to split this species and many others based on small qualitative physical differences between different geographic populations, based on small sample sets, and often without publishing any research supporting their positions. This proved controversial among mammalogists.[5][6][7][17] Despite the stipulations Groves and Grubb set out with regards to how their species concept should discriminate between species, the skeletal morphometrics they publish show that the four East African topi species cannot be distinguished from each other, as the two taxa in North and West Africa cannot. Barring that, the main criteria for recognising species in these two groups is the authors' opinion on the hair colour of a limited number of specimen skins, with the different species being (ranges in) various shades of brown. The rapid increase in recognised species which could not reliably told apart was termed "taxonomic inflation" by some.[18]

As of 2021 the ASM Mammal Diversity Database thus decided to reject the Groves and Grubb taxonomic interpretation of the topi in its entirety, and in this case also reject the 2005 Mammal Species of the World, essentially reverting to the 1972 Ansell view with the addition of superstes as a synonym of D. lunatus.[17]

Topi

[edit]To the north of Lake Bangweulu in Zambia, across the border and beyond the rift valley, above the north shore of Lake Rukwa in Tanzania, the topi subspecies that occurs there is generally recognised as Damaliscus lunatus jimela, and usually just called a 'topi'. This subspecies has horns with a lyrate profile.[4]

Description

[edit]

Adult topi are 150 to 230 cm in length.[9] They are quite large animals, with males weighing 137 kg and females weighing 120 kg, on average.[19] Their horns range from 37 cm for females to 40 cm for males. For males, horn size plays an important role in territory defence and mate attraction, although horn size is not positively correlated with territorial factors of mate selection.[19] Their bodies are chestnut brown[20] or reddish brown.[21] They have a mask-like dark colouration on the face and their tail tufts are black; the upper forelimbs and thighs have greyish, dark purple or bluish-black-coloured patches.[21][20] Their hindlimbs are brownish-yellow to yellow and their bellies are white.[20] In the wild, topi usually live a maximum of 15 years, but in general, their average lifespan is much less.[20]

Topi resemble hartebeest but have a darker colouration and lack sharply angled horns. They have elongated heads, and a distinct hump at the base of the neck. Their horns are ringed and lyrate-shaped.[21] Their coats are made of short, shiny hairs.[22] They range in mass from 68 to 160 kg (150 to 353 lb). Head-and-body length can range from 150 to 210 cm (59 to 83 in) and the tail measures 40–60 cm (16–24 in). They are a tall species, ranging in height from 100 to 130 cm (39 to 51 in) at the shoulder.[23][24] Males tend to be larger and darker than females. Topi also have preorbital glands that secrete clear oil and the front legs have hoof glands.[21]

Characteristic of this antelope species is the groaning sound it makes as it dies.[25]

Topi spoor is very similar to that of oryx and hartebeest. The tracks are about 8 cm in length, the two impressed hooves are narrow and point inward distally, and the base of the hooves are bulbous and more deeply indented into the soil than the rest of the track.[26]

Tsessebe

[edit]The most significant difference between the tsessebe, the southernmost subspecies, and the other topi subspecies is the incline of the horns, with the tsessebe having horns which are placed further apart from each other as one moves distally. This has the effect of the space between them having a more lunate profile when seen from a certain angle, as opposed to lyrate, more like that of a hartebeest. Tsessebe populations show variation as one moves from South Africa to Botswana, with southerly populations having on average the lightest pelage colour, smallest size and the least robust horns. Common tsessebe do not differ significantly from the Bangweulu tsessebe, the northernmost population, but in general the populations from that part of Zambia are on average the darkest-coloured and have the most robust horns, although differences are slight and individuals in both populations show variation in these characteristics which almost completely overlap each other.[4]

Distribution

[edit]The topi has a long but patchy distribution in Southern, East and West Africa it prefers certain grasslands in arid and savanna biomes. Human hunting and habitat modification have further isolated the subpopulations.[21] Topi are usually either numerous or absent in an area.[22] Scattered populations do not last long and either increase or die off. The health of topis in a population depends on access to green vegetation.[22] Herds of topi migrate between pastures. A large migration is in the Serengeti, where they join the wildebeests, zebras and gazelles.[27]

Topi herds can take the form of "perennially sedentary-dispersion", "perennially mobile-aggregated" or something in between. This depends on the habitat and ecology of the areas they are in. Males establish territories that attract herds of females with their offspring. Depending on the size of the patches, territories can be as large as 4 km2 and sometimes border each other. In more densely populated areas, like those of Queen Elizabeth National Park in Uganda, topis move across the plain and set up territories during resting periods.[21]

Ecology

[edit]Habitat

[edit]Topi are primarily found in grasslands, treeless open plains, and lightly wooded savannas. They prefer flat lowlands but they are also occasionally found in rolling uplands (for example in Rwanda), and are very rarely seen at higher altitudes than 1500m above sea level. In ecotone habitats between woodlands and open grasslands, they stay along the edge using the shade in hot weather. Topi use vantage points, such as termite mounds, to get a good look at their surroundings.[21]

Population studies appear to show that, relative to many of the other, somewhat more charismatic antelopes, these animals are habitat specialists, with a strong preference for seasonally dry grasslands.[28][29] In Botswana, they spend most of their time in open habitats, primarily grassland, but will retreat to mopane woodland during the rainy season.[29]

Diet

[edit]Topi are grazing herbivores,[30] their diet is almost exclusively grass. The topi is a selective feeder and uses its elongated muzzle and flexible lips to forage for the youngest blades of grass. Topi are not as capable as other grazers at feeding from short sward, and during the rainy season avoid both long mature grass and very short pasture, whereas in the dry season they move to any area with the most grass.[21] When they have access to enough green vegetation, topi usually do not need to drink.[21][31] They drink more when relying on dry grass.[31]

Topi found in the Serengeti usually feed in the morning between 8:00 and 9:00 am and in the afternoon after 4:00 pm. The periods before and after feeding are spent resting and digesting or watering during dry seasons. Topi can travel up to five kilometres to reach a viable water source. To avoid encounters with territorial males or females, topi usually travel along territorial borders, though it leaves them open to attacks by lions and leopards.[21]

Predators

[edit]Predators of topi include lions, cheetahs, african wild dogs and spotted hyenas, with jackals being predators of newborns. They are especially targeted by hyenas.[32] Nevertheless, topi tend to have a low predation rate when other species are present.[21]

Behaviour

[edit]Topi declare their territory through a variety of behaviours. Territorial behaviour includes moving in an erect posture, high-stepping, defecating in a crouch stance, ground-horning, mud packing, shoulder-wiping and grunting.[21]

The most important aggressive display of territorial dominance is in the horning of the ground. Another far more curious form of territory marking is through the anointing of their foreheads and horns with secretions from glands near their eyes. Topi accomplish this by inserting grass stems into their preorbital glands to coat them with secretion, then waving it around, letting the secretions fall onto their heads and horns. This process is not as commonly seen as ground-horning, nor is its purpose as well known. When the resident male of a territory is absent, the dominant female may assume his behaviours, defending against outside topis of either sex using the rocking canter and performing the high-stepping display.[21]

Several of their behaviours strike scientists as peculiar, such as the observed habit of topi to sleep with their mouths touching the ground and their horns sticking straight up into the air, perhaps a meager attempt at self-defense when sleeping. Male topi have also been observed standing in parallel ranks with their eyes closed, bobbing their heads back and forth. These habits are peculiar as scientists have yet to find a proper explanation for their purposes or functions.[21]

Reproduction

[edit]Topi reproduce at a rate of one calf per year per mating couple.[9]

The breeding process starts with the development of a lek. Leks are established by the congregation of adult males in an area that females visit only for mating. Lekking is of particular interest since the female choice of a mate in the lek area is independent of any direct male influence. Several options are available to explain how females choose a mate, but the most interesting is in the way the male is grouped in the middle of a lek.[33] Dominant males occupy the centre of the leks, so females are more likely to mate at the centre than at the periphery of the lek.[30]

The grouping of males can appeal to females for several reasons. First, groups of males can protect from predators. Secondly, if males group in an area with a low food supply, it prevents competition between males and females for resources. Finally, the grouping of males provides females with a wider variety of mates to choose from, as they are all located in one central area.[33]

A study by Bro-Jørgensen (2003) allowed a closer look into lek dynamics. The closer a male is to the centre of the lek, the greater his mating success rate. For a male to reach the centre of the lek, he must be strong enough to outcompete other males. Once a male's territory is established in the middle of the lek, it is maintained for quite a while; even if an area opens up at the centre, males rarely move to fill it unless they can outcompete the large males already present. However, maintaining central lek territory has many physical drawbacks. For example, males are often wounded in the process of defending their territory from hyenas and other males.[34]

In areas such as the Akagera National Park in Rwanda and Masai Mara National Reserve in Kenya, topi males establish leks which are territories that are clustered together.[35] These territories have little value outside of the males in them. The most dominant males occupy the centre of the lek cluster and the less dominant occupy the periphery.[34] Males mark their territories with dung piles and stand on them in an erect posture ready to fight any other male that tries to invade.[27] Oestrous females enter the leks both alone and in groups and mate with the males in the centre of the lek cluster.[21] Males further from the centre may increase their reproductive success if they are near water.[34] Females will compete with each other for the dominant males as females come into oestrous for only one day of the year. Females prefer to mate with dominant males that they have mated with before, however males try to mate with as many new females as possible. As such favoured males prefer to balance mating investment equally between females.[36] Females, however, will aggressively disrupt copulations that their favoured males have with other females. Subordinate females have their copulations interrupted more often than dominant females. Males will eventually counter-attack these females, refusing to mate with them any more.[36]

The parenting of the topi has characteristics of both the "hider" system (found in the blesbok) and the "follower" system (found in the blue wildebeest).[21] Calves can follow their mothers immediately after birth[27] and "may not 'lie out'". On the other hand, females separate themselves from the herd to calve and calves commonly seek hiding places during the night. A young topi stays with its mother for a year or until a new calf is born. Both yearling males and females can be found in bachelor herds.[21]

Conservation status

[edit]The total population of Damaliscus lunatus was estimated to be 300,000 by the IUCN in 1998, so it was assessed at 'lower risk (conservation dependent)', and stated to be declining.[2] In the 2008 IUCN Red List assessment the total estimated population had risen to 402,850-404,350 based on revisions of the 1998 estimate, although this was likely an underestimate and did not include the growth in tsessebe populations. It was thus assessed as 'least concern', although the IUCN continued to believe that there was a declining trend.[8][2] In 2016 it was again assessed as 'least concern', with the total population, again derived from the 1998 numbers adjusted for new information, rising to 404,850-406,350, with the IUCN continuing to claim it was declining. The growth of the tsessebe populations were again not included.[1]

Common tsessebe

[edit]In 1998 the IUCN estimated a total tsessebe population of 30,000, including the Bangweulu animals. It was assessed as 'lower risk (conservation dependent)'.[2] In the 2016 update to the Red List of Mammals of South Africa, Swaziland and Lesotho, the minimum South African population was estimated as 2,256–2,803 individuals, of which the total minimum mature population size was 1,353–1,962; this was believed to be a significant underestimate, due to not getting enough responses from private game reserves on time for publication.[28]

During 1980s and 1990s tsessebe populations in South Africa and Zimbabwe declined significantly, especially in the National Parks. In 1999 the populations stabilised and began to grow again, especially in private game reserves. There were a number of different theories advanced as to what was causing this decline, while other species were doing well.[28] One 2006 theory for this decline was that woody plant encroachment was playing a primary role.[37] As of 2016, interspecific competition is believed to have played a primary role, with the decline in tsessebe being caused by the proliferation of other antelope species, which was itself due to the opening of man-made watering holes in the game parks. Closing watering holes is believed to increase habitat heterogeneity in the parks, which would favour the tsessebe.[28]

Initially an uncommon animal, in the 2000s the population on private game reserves in both South Africa and Zimbabwe, primarily stocked for the trophy hunting industry, began to grow quickly, with large jumps seen in the 2010s. As a large percentage of these animals are found in wild conditions in their natural areas of distribution, this is seen as contributing to the recovery of the species in South Africa. Nonetheless, there are some questions as to the potential danger of it hybridising with the also native red hartebeest which are common throughout its range, and with which hybrids have been recorded in both ranches and in National Parks. Such hybrids are likely fully fertile, and some fear such miscegenation could potentially pollute the gene pool in the future.[28]

In northern Botswana, on the other hand, populations declined from 1996 to 2013, tsessebe populations in the Okavango Delta declined by 73%, with a 87% decline in the Moremi Game Reserve in particular.[29] A study compared the situation with around Lake Rukwa in Tanzania in the 1950s, a paper about game populations and the elephant problem, which might create the open habitat required through their bulldozing behaviour.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (7 January 2016). "Topi (Damaliscus lunatus)". IUCN Red List. IUCN. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d East, Rod; IUCN/SSC Antelope Specialist Group (1998). "African Antelope Database" (PDF). Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission. 21: 200–207. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ a b Damaliscus lunatus, MSW3

- ^ a b c d Cotterill, Fenton Peter David (January 2003). "Insights into the taxonomy of tsessebe antelopes, Damaliscus lunatus (Bovidae: Alcelaphini) in south-central Africa: with the description of a new evolutionary species". Durban Museum Novitates. 28: 11–30. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ a b "About the Mammal Diversity Database". ASM Mammal Diversity Database. American Society of Mammalogists. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ a b Holbrook, Luke Thomas (June 2013). "Taxonomy Interrupted". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 20 (2): 153–154. doi:10.1007/s10914-012-9206-1. S2CID 17640424. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ a b Gutiérrez, Eliécer E.; Garbino, Guilherme Siniciato Terra (March 2018). "Species delimitation based on diagnosis and monophyly, and its importance for advancing mammalian taxonomy". Zoological Research. 39 (3): 301–308. doi:10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2018.037. PMC 6102684. PMID 29551763. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ a b IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (30 June 2008). "Topi (Damaliscus lunatus)". IUCN Red List. IUCN. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- ^ a b c d Kingdon, Jonathan (23 April 2015). The Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. pp. 428–431. ISBN 9781472921352.

- ^ a b Sclater, Philip Lutley; Thomas, Oldfield; Wolf, Joseph (January 1895). The Book of Antelopes. Vol. 1. London: R.H. Porter. p. 86. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.65969. OCLC 1236807.

- ^ Matschie, Paul (1895). Die Säugthiere Deutsch-Ost-Afrikas (in German). Berlin: Dietrich Reimer. pp. 111–112. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.14826. OCLC 12266224.

- ^ Cuvier, Georges (1827). Griffith, Edward (ed.). Règne animal [The animal kingdom : arranged in conformity with its organization The class Mammalia]. Vol. 4. Translated by Hamilton-Smith, Charles. London: Geo. B. Whittaker. pp. 352–354. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.45021. OCLC 1947779.

- ^ Natural History Museum (BM) (19 April 2013). "Clapperton, Bain Hugh (1788-1827)". JSTOR. Ithaka. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Lydekker, Richard (1908). The game animals of Africa. London: R. Ward, limited. pp. 116–121. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.21674. OCLC 5266086.

- ^ Macdonald, D. W. (2006). Encyclopedia of Mammals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (30 June 2008). "Damaliscus lunatus ssp. superstes (Bangweulu Tsessebe)". Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. Retrieved 2018-11-15.

- ^ a b c "Damaliscus lunatus (Burchell, 1824)". ASM Mammal Diversity Database. American Society of Mammalogists. 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ Heller, Rasmus; Frandsen, Peter; Lorenzen, Eline Deirdre; Siegismund, Hans R. (September 2014). "Is Diagnosability an Indicator of Speciation? Response to "Why One Century of Phenetics Is Enough"". Systematic Biology. 63 (5): 833–837. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syu034. hdl:10400.7/567. PMID 24831669.

- ^ a b Bro-Jørgensen, J (2007). "The Intensity of Sexual Selection Predicts Weapon Size in Male Bovids". Evolution. 61 (6): 1316–1326. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00111.x. PMID 17542842. S2CID 24278541.

- ^ a b c d Haltenorth, T (1980). The Collins Field Guide to the Mammals of African Including Madagascar. New York, NY: The Stephen Greene Press, Inc. pp. 81–82.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Estes, R. D. (1991). The Behavior Guide to African Mammals, Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, Primates. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. pp. 142–146. ISBN 9780520080850.

- ^ a b c Kingdon, J. (1979). East African Mammals: An Atlas of Evolution in Africa, Volume 3, Part. D: Bovids. University Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 485–501

- ^ Burnie D and Wilson DE (Eds.) 2005. Animal: The Definitive Visual Guide to the World's Wildlife. DK Adult ISBN 0789477645

- ^ Topi videos, photos and facts – Damaliscus lunatus Archived 2012-08-25 at the Wayback Machine. ARKive. Retrieved on 2013-01-16.

- ^ Lubbe, P. (1982). Wêreldspektrum (in Afrikaans). Vol. 2. Ensiklopedie Afrikana. pp. 192, 193. ISBN 0908409435.

- ^ Gutteridge, Lee; Liebenberg, Louis (2013). The Mammals of Southern African and their Tracks & Signs. Johannesburg: Jacana Media. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-4314-0806-1.

- ^ a b c Jarman, P. J. (1974). "The social organisation of antelope in relation to their ecology" (PDF). Behaviour. 48 (3/4): 215–267. doi:10.1163/156853974X00345.

- ^ a b c d e Nel, P.; Schulze, E.; Goodman, P.; Child, M. F. (2016). "A conservation assessment of Damaliscus lunatus lunatus" (PDF). The Red List of Mammals of South Africa, Swaziland and Lesotho. South African National Biodiversity Institute and Endangered Wildlife Trust, South Africa. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-04-23. Retrieved 2022-05-18.

- ^ a b c Reeves, Harriet (2018). "Okavango Tsessebe Project". Wilderness Wildlife Trust. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ a b Bro-Jørgensen, J (2003). "The Significance of Hotspots to Lekking Topi Antelopes (Damaliscus lunatus)" (PDF). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 53 (5): 324–331. doi:10.1007/s00265-002-0573-0. S2CID 52829538. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-12-12. Retrieved 2017-12-11.

- ^ a b Huntley, B. J. (1972). "Observations of the Percy Fyfe Nature Reserve tsessebe population". Annals of the Transvaal Museum. 27: 225–43. hdl:10520/AJA00411752_267.

- ^ Bro-Jørgensen, J. (2002). "Overt female mate competition and preference for central males in a lekking antelope". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99 (14): 9290–9293. doi:10.1073/pnas.142125899. PMC 123133. PMID 12089329.

- ^ a b Bateson, Patrick (1985). Mate Choice. New York, NY: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. pp. 109–112. ISBN 978-0-521-27207-0.

- ^ a b c Bro-Jørgensen, Jakob; Durant, Sarah M. (2003). "Mating Strategies of Topi Bulls: Getting in the centre of attention" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 65 (3): 585–594. doi:10.1006/anbe.2003.2077. S2CID 54229602. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-03-08. Retrieved 2021-04-27.

- ^ Bro-Jørgensen, J. (2003). "No peace for estrous topi cows on leks" (PDF). Behavioral Ecology. 14 (4): 521–525. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.497.2682. doi:10.1093/beheco/arg026.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Bro-Jørgensen, Jakob (2007). "Reversed Sexual Conflict in a Promiscuous Antelope" (PDF). Current Biology. 17 (24): 2157–2161. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.11.026. PMID 18060785. S2CID 14925690. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-04-27. Retrieved 2022-05-18.

- ^ Dorgeloh, Werner G. (2006). "Habitat Suitability for tsessebe Damaliscus lunatus lunatus". African Journal of Ecology. 44 (3): 329–336. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2006.00654.x.

External links

[edit]- IUCN Red List least concern species

- Damaliscus

- Mammals of the Central African Republic

- Mammals of Chad

- Mammals of Ethiopia

- Mammals of Kenya

- Mammals of Rwanda

- Mammals of Somalia

- Mammals of Sudan

- Mammals of Tanzania

- Mammals of Uganda

- Fauna of East Africa

- Bovids of Africa

- Mammals described in 1824

- Taxa named by William John Burchell