Temple of Castor and Pollux

Temple of Castor and Pollux | |

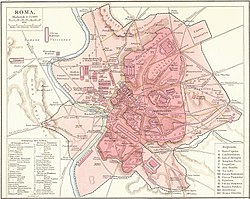

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| Location | Regio VIII Forum Romanum |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°53′30″N 12°29′08″E / 41.89167°N 12.48556°E |

| Type | Roman Temple |

| History | |

| Builder | Roman Republic |

| Founded | 495 BC |

The Temple of Castor and Pollux (Italian: Tempio dei Dioscuri) is an ancient temple in the Roman Forum, Rome, Central Italy.[1] It was originally built in gratitude for victory at the Battle of Lake Regillus (495 BC). Castor and Pollux (Greek Polydeuces) were the Dioscuri, the "twins" of Gemini, the twin sons of Zeus (Jupiter) and Leda. Their cult came to Rome from Greece via Magna Graecia and the Greek culture of Southern Italy.[2]

The Roman temple is one of a number of known Dioscuri temples remaining from antiquity.

Founding

[edit]The last king of Rome, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, and his allies, the Latins, waged war on the infant Roman Republic. Before the battle, the Roman dictator Aulus Postumius Albus Regillensis vowed to build a temple to the Dioscuri (Castor and Pollux) if the Republic were victorious.

According to legend, Castor and Pollux appeared on the battlefield as two able horsemen in aid of the Republic; and after the battle had been won they again appeared on the Forum in Rome watering their horses at the Spring of Juturna thereby announcing the victory. The temple stands on the supposed spot of their appearance.

One of Postumius’ sons was elected duumvir in order to dedicate the temple on 15 July (the ides of July) 484 BC.[3]

History

[edit]During the Republican period, the temple served as a meeting place for the Roman Senate, and from the middle of the 2nd century BC the front of the podium served as a speaker's platform. During the imperial period, the temple housed the office for weights and measures, and was a depository for the State treasury. Chambers located between the foundation piers of the temple were used to conduct this business. Based on finds from the drains, one of the chambers was likely used by a dentist.[4]

The archaic temple was completely reconstructed and enlarged in 117 BC by Lucius Caecilius Metellus Dalmaticus after his victory over the Dalmatians. Gaius Verres again restored this second temple in 73 BC.

Commemorating the initial victory at Lake Regillus, a large cavalry parade was held each year on July 15 and featured as many as 5,000 young men carrying shields and spears. Two young men, riding white horses, led the parade and represented Castor and Pollux.[5]

In 14 BC a fire that ravaged major parts of the forum destroyed the temple, and Tiberius, the son of Livia by a previous marriage and adopted son of Augustus and the eventual heir to the throne, rebuilt it. Tiberius' temple was dedicated in 6 AD. The remains visible today are from the temple of Tiberius, except the podium, which is from the time of Metellus.

In conjunction with this imperial rebuilding, the cult itself became associated with the imperial family. Initially, the twins were identified with Augustus's intended heirs, Gaius and Lucius Caesar. After their premature deaths, however, the association with Castor and Pollux passed to Tiberius and his brother Drusus.[5]

According to Edward Gibbon, the temple of Castor served as a secret meeting place for the Roman Senate. Frequent meetings of the Senate are also reported by Cicero.[6] Gibbon said the senate was roused to rebellion against Emperor Maximinus Thrax and in favor of emperor Gordian I and his son Gordian II at the Temple of Castor in 237 AD.[7][8]

If still in use by the 4th-century, the temple would have been closed during the persecution of pagans in the late Roman Empire. The temple was possibly already falling apart in the fourth century, when a wall in front of the Lacus Juturnae was erected from reused material. Nothing is known of its subsequent history, except that in the 15th century, only three columns of its original structure were still standing. The street running by the building was called via Trium Columnarum.

In 1760, the Conservatori, finding the columns in a state of imminent collapse, erected scaffolding for effecting repairs. Both Piranesi and the young English architect George Dance the Younger were able to climb up and make accurate measurements; Dance had "a Model cast from the finest Example of the Corinthian order perhaps in the whole World", as he reported to his father.[9]

Today the podium survives without the facing, as do the three columns and a piece of the entablature, one of the most famous features in the Forum.

Architecture

[edit]The octastyle temple was peripteral, with eight Corinthian columns at the short sides and eleven on the long sides. There was a single cella paved with mosaics. The podium measures 32 m × 49.5 m (105 ft × 162 ft) and 7 m (23 ft) in height. The building was constructed in opus caementicium and originally covered with slabs of tuff which were later removed. According to ancient sources, the temple had a single central stairway to access the podium, but excavations have identified two side stairs.

Archaeology

[edit]The temple complex was excavated and studied between 1983 and 1989 by a joint archaeological mission of the Nordic academies in Rome, led by Inge Nielsen and B. Poulsen.[10]

Other Temples of Castor and Pollux

[edit]The Roman temple is one of a number of known Dioscuri sites remaining from antiquity. Among others,

- the Baroque basilica church of San Paolo Maggiore in Naples is built on the site of a Temple of Castor and Pollux. Its porch and pediment survived until the 1688 Sannio earthquake; only three Corinthian columns remain, incorporated into the facade of the church.

- The vanished Anakeion near the Acropolis in Athens was a Dioscuri temple. Writing in about 150 AD, Pausanias described it as ancient.[11]

- Pausanias identified another temple in Argos depicting Castor and Pollux, their sons Anaxias and Mnasinus, and their wives Hilaeira and Phoebe.

- The extensive ruins of the Valle dei Templi in Agrigento, Sicily, include the site of another Temple of the Dioscuri.

In his 1888 description of the Dioscuri temple in ancient Greek colonial city of Naucratis in Egypt, Ernest Arthur Gardner remarked that such temples were common enough to have a characteristic orientation. Temples to the gods tended to face east. Temples to heroes and demi-gods such as Castor and Pollux faced west.[12]

Gallery

[edit]-

Another view of the three columns of the Temple of Castor and Pollux

-

The Temple of Castor and Pollux (right) with the Temple of Vesta to the left

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Richardson, Jr., L. (1 October 1992). A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. JHU Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-8018-4300-6.

- ^ Parker, John Henry (1879). The Archaeology of Rome: Forum romanum et magnum. Vol. 5 (2nd ed.). J. Parker. p. 33.

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita, 2.42

- ^ Claridge, Amanda (2010). Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. p. 94.

- ^ a b Claridge, Amanda (2010). Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. p. 95.

- ^ Cicero, In Verrem 2.1.129

- ^ Historia Augusta. p. 159.

- ^ Edward, Gibbon. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Vol. I. pp. 192, 193.

- ^ Quoted in Frank Salmon, "'Storming the Campo Vaccino': British Architects and the Antique Buildings of Rome after Waterloo" Architectural History 38 (1995:146-175) p. 149f.

- ^ Pia Guldager Bilde; Birte Poulsen (2008). The Temple of Castor and Pollux Ii,1: The Finds. L'ERMA di BRETSCHNEIDER. pp. 141–. ISBN 978-88-8265-463-4.

- ^ Jones, W. H.; Ormerod, H. A. (1918). Pausanias Description of Greece. Harvard University Press. Archived from the original on 15 March 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ^ Gardner, Ernest Arthur (1 January 1888). Naukratis II. Egypt Exploration Fund. pp. 30–31. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Champlin, Edward J. 2011. “Tiberius and the Heavenly Twins.” The Journal of Roman Studies 101: 73–99.

- Kalas, Gregor. 2015. The Restoration of the Roman Forum in Late Antiquity: Transforming Public Space. Ashley and Peter Larkin Series in Greek and Roman Culture. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press.[ISBN missing]

- McIntyre, Gwynaeth. 2018. "Maxentius, the Dioscuri, and the Legitimisation of Imperial Power." Antichthon 52: 161–180.

- Nilson, Kjell Aage, Claes B. Persson, Siri Sande, Jan Zahle. 2009. The Temple of Castor and Pollux III: The Augustan Temple. Occasional papers of the Nordic Institutes in Rome, 4. Roma: "L'Erma" di Bretschneider.

- Poulsen, Birte. 1991. “The Dioscuri and Ruler Ideology.” Symbolae Osloenses LXVI: 119–146.

- Rebeggiani, Stefano. 2013. "Reading the Republican Forum: Virgil's Aeneid, the Dioscuri, and the Battle of Lake Regillus." Classical Philology 108.1: 53–69.

- Richardson, J.H. 2013. "The Dioscuri and the Liberty of the Republic." Latomus 72.4: 901–918.

- Stamper, John W. 2005. The Architecture of Roman Temples: The Republic to the Middle Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sumi, S. Geoffrey. 2009. "Monuments and Memory: The Aedes Castoris in the Formation of Augustan Ideology." Classical Quarterly 59.1: 167–186.

- Tucci, P. L. 2013. “The Marble Plan of the Via Anicia and the Temple of Castor and Pollux "in Circo Flaminio": The State of the Question.” Papers of the British School at Rome 81: 91–127.

- Van den Hoek, Annewies. 2013. “Divine Twins or Saintly Twins: The Dioscuri in an Early Christian Context.” In Pottery, Pavements, and Paradise: Iconographic and Textual Studies on Late Antiquity, Edited by Annewies Van den Hoek and John. J. Hermann. Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae 122, 255–300. Leiden; Boston: Brill.[ISBN missing]

External links

[edit]- Aedes Castoris in Foro Romano (Platner's Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome, with further links)

- Temple of the Dioscuri at digitales Forum Romanum by Humboldt University of Berlin Archived 2021-11-17 at the Wayback Machine