Temple of Jupiter Tonans

Aedes Iovis Tonantis | |

| |

| Location | Area Capitolina, Capitoline Hill, Rome |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°53′31″N 12°29′1″E / 41.89194°N 12.48361°E |

| History | |

| Builder | Augustus Caesar |

| Founded | 22 BCE |

| Periods | Roman Empire |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1811–1812 |

| Archaeologists | |

| Condition | Ruined |

The Temple of Jupiter Tonans (Latin: Aedes Iovis Tonantis, lit. 'Temple of Jupiter the Thunderer') was a small temple in Rome, dedicated by Augustus Caesar in 22 BCE to Jupiter, the chief god of ancient Rome. It was probably situated at the entrance to the Area Capitolina, the sanctuary of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill, near the much older and larger Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus. The temple was considered among Augustus's most impressive archaeological projects, and played an important role in the Secular Games, a religious and artistic festival that he revived in 17 BCE. It was also noted by Roman authors for the artworks, particularly statues, displayed in and around it.

Much of the temple's history is unclear, though it was mentioned in a fourth-century CE panegyric and may have been restored around the beginning of the second century CE. Nothing, except perhaps a small part of its foundations, survives of the temple. From 1555 until the nineteenth century, the Temple of Vespasian and Titus in the Roman Forum was misidentified as the Temple of Jupiter Tonans, but the Italian archaeologist Luigi Canina correctly identified the former temple during excavations in 1844.

History

[edit]The temple was the third of four temples in Rome built by the emperor Augustus, after the Temple of Caesar and the Temple of Apollo Palatinus (dedicated in 29 and 28 BCE respectively) and before the Temple of Mars Ultor, dedicated in 2 BCE.[1] Augustus vowed its dedication in 26 BCE to celebrate his escape from being struck by lightning while on a military campaign in Spain against the Cantabri.[2] It was consecrated on 1 September 22 BCE.[3] According to the French archaeologist Pierre Gros, construction likely began in the middle of 24 BCE, after Augustus's return to Rome from Spain.[3]

During the Secular Games, a religious and artistic festival revived by Augustus in 17 BCE and celebrated periodically thereafter,[4] the temple was used as one of four centres from which the fifteen priests known as the quindecimviri sacris faciundis would issue purifying agents (purgamenta) – torches, sulphur and bitumen – to the Roman people.[6]

According to Augustus's biographer Suetonius, it was among Augustus's most important architectural works, alongside the Forum of Augustus, the Temple of Mars Ultor and the Temple of Apollo Palatinus.[7] Augustus himself visited the temple frequently.[8] It was considered to be comparatively small.[9] Unusually for Roman temples, its walls were constructed entirely of solid blocks of marble.[3] According to a depiction of the temple on a coin of Augustus, minted around 19 BCE, its portico was hexastyle (that is, constructed with six columns across its front) and built in the Corinthian order.[10]

According to the Roman polymath Pliny the Elder, writing in the first century CE, the temple contained a bronze cult statue of Zeus (the Greek counterpart of Jupiter) made by the fourth-century BCE Athenian sculptor Leochares,[3] while statues of the deities Castor and Pollux by the fifth-century Corinthian sculptor Euphranor were situated in front of the temple.[11] The inclusion of statues by noted Greek artists, especially of the fourth and fifth centuries BCE and the archaic period, was almost universal in the temples built or restored by Augustus in Rome, and has been described by the modern archaeologist Susan Walker as a means of turning Rome into a "moral museum".[12]

According to an anecdote related by Suetonius, Augustus dreamed that Jupiter had castigated him for building the temple, as it had reduced the number of visitors to the older and grander Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus on the same hill: in response, Augustus declared the Temple of Jupiter Tonans to be merely a gatekeeper to that of Jupiter Capitolinus, and hung bells (tinnitabula), which were often hung on the doors of houses, on its pediment.[13] Gros has suggested that this story may have been concocted to explain an older, forgotten belief, by which the bells were intended to serve an apotropaic (protective) function against lightning.[3]

The temple is not known to have featured among the extensive reconstructions undertaken by the emperor Domitian (r. 81–96 CE) following the Great Fire of Rome in 64 CE. A relief on the early second-century CE Tomb of the Haterii shows a hexastyle temple which might be that of Jupiter Tonans.[14] It is generally held that this relief shows public monuments worked on by the tomb's founder, Quintus Haterius, a redemptor (building contractor).[15] It was mentioned in a panegyric by the fourth-century CE poet Claudian.[16] It is not clear whether other references to the temple in Latin poetry, such as by the first-century CE poet Statius, likely refer to this structure or to the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus.[17]

In 1555, the Italian architect Pirro Ligorio misidentified the partial remains of the Temple of Vespasian and Titus in the Roman Forum as belonging to the Temple of Jupiter Tonans,[18] and these ruins were mislabelled as such in an engraving by the eighteenth-century Italian artist Giovanni Battista Piranesi.[19] Excavations begun in 1811–1812 by the papal architect Giuseppe Camporese eventually confirmed the correct identification of the ruins, though it was not until 1844 that the archaeologist Luigi Canina labelled them as such.[20] A concrete foundation between the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus and the Temple of Saturn has been conjectured as part of the Temple of Jupiter Tonans, but otherwise no remains of the temple are known to have survived.[21]

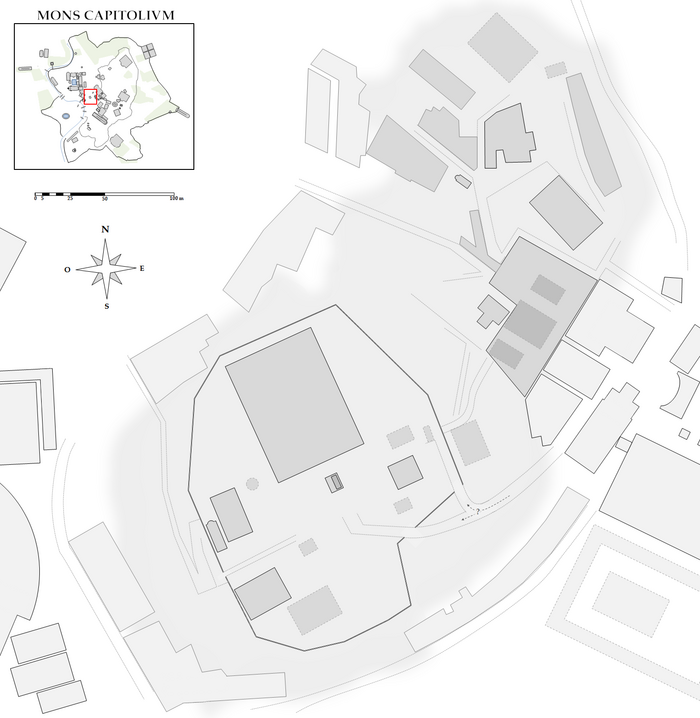

Location on the Capitoline Hill

[edit]The precise location of the temple is uncertain; it is believed to have located towards the south-east of the Capitoline.[22] Based on Suetonius's comment about it being a "doorkeeper" to the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, it is considered to have been located close to the entrance to the Area Capitolina, the sanctuary of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill.[2] A tentative identification has been made between the temple and a building shown at the eastern edge of the Area Capitolina on the third-century CE map of Rome known as the Forma Urbis Romae.[14]

| Capitoline Hill plan |

|---|

Iseum

Temple of

Concord (?) Altar

Centus

Gradus Porta Pandana

Inter duos lucos

Temple of

Fides (?) Temple

of Ops(?) |

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Hekster & Rich 2006, p. 153.

- ^ a b Platner & Ashby 1929, p. 305.

- ^ a b c d e f Gros 1997, p. 159.

- ^ Turcan 2013, p. 83.

- ^ Forsythe 2012, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Forsythe 2012, pp. 73–74. The other three locations were the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, the Temple of Apollo Palatinus and the Temple of Diana on the Aventine.[5]

- ^ Babcock 1967, p. 189. Suetonius, at Divus Augustus 29.1–3, uses the phrase inter opera praecipua .

- ^ Lewis 2023, p. 313.

- ^ Fishwick 2014, p. 68.

- ^ Platner & Ashby 1929, p. 305; Gros 1997, p. 160.

- ^ Platner & Ashby 1929, p. 305, citing Pliny, Natural History 34.77–78.

- ^ Walker 2000, pp. 61, 71.

- ^ Platner & Ashby 1929, p. 305, citing Suetonius, Divus Augustus [1]. The Roman historian Cassius Dio says that the bells were placed on the cult statue.[3]

- ^ a b Gros 1997, p. 160.

- ^ Lancaster 2005, p. 19.

- ^ Gros 1997, p. 160, citing Claudian, De Sexto Consulatu Honorii Augusti 47

- ^ Newlands 2002, p. 169; Platner & Ashby 1929, p. 305.

- ^ Gorski & Packer 2015, p. 186.

- ^ Ridley 2000, p. 414; Wood 2021, p. 164.

- ^ Gorski & Packer 2015, p. 189.

- ^ Aicher 2004, p. 62.

- ^ British Museum 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Aicher, Peter J. (2004). Rome Alive: A Source-Guide to the Ancient City. Vol. 1. Wauconda: Bolchazy-Carducci. ISBN 978-0-86516-473-4.

- Babcock, Charles L. (1967). "Horace Carm. 1. 32 and the Dedication of the Temple of Apollo Palatinus". Classical Philology. 62 (3): 189–194. doi:10.1086/365257. JSTOR 268380. S2CID 162618366.

- British Museum (2020-05-23). "Temple of Jove the Thunderer". Archived from the original on 2022-03-24. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- Fishwick, Duncan (2014). Cult Places and Cult Personnel in the Roman Empire. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-94027-5.

- Forsythe, Gary (2012). Time in Roman Religion: One Thousand Years of Religious History. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-31441-4.

- Gorski, Gilbert J.; Packer, James E. (2015). The Roman Forum: A Reconstruction and Architectural Guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19244-6.

- Gros, Pierre (1997). "Iuppiter Tonans". In Steinby, Eva Margareta (ed.). Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae (in French). Vol. 3. Rome: Edizioni Quazar. pp. 159–160. ISBN 978-88-7140-096-9.

- Hekster, Olivier; Rich, John (2006). "Octavian and the Thunderbolt: the Temple of Apollo Palatinus and Roman Traditions of Temple Building". The Classical Quarterly. 56 (1): 149–168. doi:10.1017/S0009838806000127. hdl:2066/42841. JSTOR 4493394. S2CID 170382655.

- Lancaster, Lynne C. (2005). Concrete Vaulted Construction in Imperial Rome: Innovations in Context. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511610516. ISBN 978-0-511-61051-6.

- Lewis, Anne-Marie (2023). Celestial Inclinations: A Life of Augustus. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-759964-8.

- Newlands, Carole E. (2002). Statius' Silvae and the Poetics of Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-43270-2.

- Platner, Samuel Ball; Ashby, Thomas (1929). A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925649-5. Retrieved 2023-06-17.

- Ridley, Ronald T. (2000). The Pope's Archaeologist: The Life and Times of Carlo Fea. Rome: Edizioni Quasar. ISBN 978-88-7140-177-5.

- Turcan, Robert (2013) [1998]. The Gods of Ancient Rome: Religion in Everyday Life from Archaic to Imperial Times. Translated by Nevill, Antonia. New York: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-05850-9.

- Walker, Susan (2000). "The Moral Museum: Augustus and the City of Rome". In Coulston, Jon; Dodge, Hazel (eds.). Ancient Rome: The Archaeology of the Eternal City. Oxford: Oxford University School of Archaeology. pp. 61–75. ISBN 978-0-947816-55-1.

- Wood, Christopher S. (2021). A History of Art History. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-20476-5.