Temple of Apollo Palatinus

The surviving remains of the temple's podium, photographed in 1994 | |

| Coordinates | 41°53′20″N 12°29′09″E / 41.8888°N 12.4857°E |

|---|---|

| History | |

| Builder | Octavian |

| Founded | 28 BCE |

| Events | Destroyed on the night of 18–19 March 363 |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates |

|

| Archaeologists |

|

| Condition | Ruined |

| Management | Soprintendenza Archeologica di Roma |

| Public access | Yes |

| Designated | 1980 |

| Part of | Historic Centre of Rome |

| Reference no. | 91ter |

The Temple of Apollo Palatinus ('Palatine Apollo'), sometimes called the Temple of Actian Apollo, was a temple of the god Apollo in Rome, constructed on the Palatine Hill on the initiative of Augustus (known as "Octavian" until 27 BCE) between 36 and 28 BCE. It was the first temple to Apollo within the city's ceremonial boundaries, and the second of four temples constructed by Augustus. According to tradition, the site for the temple was chosen when it was struck by lightning, which was interpreted as a divine portent. Augustan writers situated the temple next to Augustus's personal residence, which has been controversially identified as the structure known as the domus Augusti.

The temple was closely associated with the victories of Augustus's forces at the battles of Naulochus and Actium, the latter of which was extensively memorialised through its decoration. The temple played an important role in Augustan propaganda and political ideology, in which it represented the restoration of Rome's 'golden age' and served as a signifier of Augustus's pietas (devotion to religious and political duty). It was used for the worship of Apollo and his sister Diana, as well as to store the prophetic Sibylline Books. Its precinct was used for diplomatic functions as well as for meetings of the Roman Senate, and contained the Portico of the Danaids, which included libraries of Greek and Latin literature considered among the most important in Rome.

Augustan poets frequently mentioned and praised the temple in their works, often commenting on its lavish artistic decoration and statuary, which included three cult statues and other works by noted Greek artists of the archaic period and the fourth century BCE. These poets included Tibullus, Virgil and Horace, whose Carmen Saeculare was first performed at the temple on 3 June 17 BCE during the Secular Games.

The Great Fire of Rome in 64 CE damaged the temple, but it was restored under the emperor Domitian (r. 81 – 96 CE). It was finally destroyed by another fire in 363 CE, which was rumoured to be an act of arson committed by Christians. The temple has been excavated and partially restored in various phases since the 1860s, though only partial remains survive and their documentation is incomplete. Modern assessments of the temple have variously treated it as an extravagant, Hellenising break with Roman tradition and as a conservative attempt to reassert the architectural and political values of the Roman Republic. It has been described by the archaeologist John Ward-Perkins as "one of the earliest and finest of the Augustan temples".[1]

History

[edit]Background

[edit]The worship of Apollo in Rome began in the fifth century BCE. According to Roman tradition, the first temple to Apollo was promised to the god in 433 BCE in return for his intercession during a plague. This temple was originally known as the Temple of Apollo Medicus and later as the Temple of Apollo Sosianus, after Gaius Sosius, who restored it around 32 BCE. It was situated in the Campus Martius, outside the ceremonial boundary (pomerium) of Rome, since Apollo, whose worship originated in the Greek world, was considered a 'foreign' deity and so unsuitable for a temple within the city.[2] According to the classicist Paul Zanker, Apollo was held in Roman culture to represent discipline, morality, purification and the punishment of excess.[3]

After securing control over the Roman state through victory in his civil war against Mark Antony, Octavian (known as "Augustus" from 27 BCE) made a political and ideological priority of the embellishment and restoration of Rome's built space. According to his biographer Suetonius, he claimed to have found Rome built of brick, and to have left it built of marble.[4] The construction and restoration of temples was a major part of this programme: Augustus claimed to have restored eighty-two of them in 28 BCE alone.[5] The archaeologist Susan Walker has described Rome under Augustus as a "moral museum", by which public architecture and artwork, particularly the display of Greek sculpture,[a] was used as part of Augustus's ideological project.[7] Augustus's developments on the Palatine Hill included the construction and restoration of several of its temples and the intensification of cult activity around it,[8] making the Palatine, previously most significant as an elite residential area,[9] Rome's "new seat of political and religious power", in the words of the classicist Ulrich Schmitzer.[10]

The Temple of Apollo Palatinus was among the earliest of a series of monuments constructed by Augustus around Rome,[11] and his first major architectural project undertaken independently in the city.[12][b] Other Augustan monuments of the same period included the restoration of the Temple of Jupiter Feretrius in 32 BCE,[14] the construction of the Mausoleum of Augustus in 28 BCE,[15] and the completion in 29 BCE of the Curia Julia, a senate house whose construction was begun in 44 BCE by Octavian's adoptive father, Julius Caesar.[16] Apollo was a favourite god of Augustus.[17] Two laurel trees, symbolic both of Apollo and of victory, stood by the side of the front door of Augustus's house, highlighting the connection between Apollo, Augustus and his victory over Mark Antony at the Battle of Actium.[18] According to a story related by Suetonius, who reports having read it in a work of the Greek author Asklepiades of Mendes, Augustus considered himself the son of Apollo, and Apollo as the patron deity of his family.[19] During the civil war, Augustus used the iconography of Apollo to contrast himself with Antony, who was closely associated with the antithetical god Dionysus; Augustus was criticised for his rumoured appearance at a feast in costume as Apollo.[20] Augustus further explained his cultivation of Apollo through the tradition that Apollo had protected the hero Aeneas, believed to have been the ancestor of the Romans and the progenitor of Augustus's family, the gens Iulia.[21]

Construction

[edit]

The dedication of temples by generals following military victories was an established part of Roman political culture in the Middle Republic (c. 200 – c. 100 BCE), but had largely fallen out of fashion by 100 BCE.[23] Octavian's vow to dedicate the temple followed the victory of his admiral Marcus Agrippa over Sextus Pompeius at the Battle of Naulochus on 3 September 36 BCE:[24][c] Octavian probably announced the temple's construction in November, during a speech to the Roman senate and people.[27] In 36 BCE, he began buying land in the area of the future temple. The Palatine was considered particularly sacred and among Rome's most fashionable residential districts,[28] and had the additional advantage of being mostly owned by private citizens, from whom Octavian was able to buy land in a private capacity. The precise location of the temple was determined when a bolt of lightning struck part of Octavian's property. On the advice of the haruspices, specialist priests who interpreted divine portents, this was considered to be an indication of a god's desire for a temple, and as urging the construction of a temple to Apollo within the city. Octavian declared that portion of his property to be public land, and initiated the construction of the temple.[29]

The temple was dedicated on 9 October 28 BCE,[30] a day traditionally associated with the worship of deities of victory.[31] The temple's dedication followed Octavian's defeat of the forces of Antony and Queen Cleopatra of Egypt at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, which was linked in Octavian's propaganda with the intercession of Apollo; in thanks for his victory, Octavian constructed a new sanctuary of Apollo at the site of his camp at Actium, and restored the god's existing sanctuary at the entrance to the Ambracian Gulf, where the battle had taken place.[32] It was the second of four temples built in Rome by Augustus, following the Temple of Caesar (dedicated in 29 BCE) and preceding the Temple of Jupiter Tonans on the Capitoline Hill (dedicated in 22) and that of Mars Ultor, dedicated in 2 BCE in Augustus's newly-built forum.[33]

The temple was formally dedicated to Apollo,[7] but considered to be dedicated both to Apollo and to his sister Diana,[34] who was closely associated with Augustus's victory at Naulochus.[35] Roman temples were often dedicated to gods under particular epithets, which could relate to the builder or location of the temple as well as to a specific aspect of the god in question.[36] Although the temple's official name was the Temple of Actian Apollo (using the epithet Actius), it was also informally known by the same god's epithets Actiacus, Navalis, Palati – all of which referred to Apollo's connection with the Battle of Actium – and Rhamnusius, an epithet of obscure significance which may have referred to the Nemeseion sanctuary at Rhamnous in Attica, sometimes believed to have been the source of the temple's cult statue.[37]

Cossutius, a brick-maker employed by Gaius Asinius Pollio – a politician and literary patron of the early Augustan era – was probably involved in the temple's construction: bricks bearing his stamp have been recovered from the temple and adjacent buildings.[38][d] Immediately adjacent to the temple,[e] the Portico of the Danaids included two libraries of Greek and Latin literature,[42] known collectively as the Library of Palatine Apollo and considered among the largest and most important libraries in Rome.[43] As well as literary works, these libraries contained artworks depicting some of their authors, and were noted as a repository of legal texts.[44] The portico was used by Augustus to hold meetings of the Roman Senate, particularly during his convalescence from illness in 23 BCE,[45][f] and to receive official guests and foreign ambassadors.[42] The surviving sources are contradictory as to the opening of the libraries; they may have been opened at the same time as the temple, or at another point before 23 BCE.[47]

Later history

[edit]After Augustus's death in 14 CE, his successors as emperor occasionally used the temple's precinct for senate meetings. His immediate successor, Tiberius, held one there in 16 CE, while at least one more under Claudius (r. 41–54 CE) is attested and was intended, in the judgement of the classicist David L. Thompson, as "a symbolic assertion of the imperial power". According to the Roman historian Tacitus, Claudius's wife Agrippina the Younger had a secret door installed in the room used for the senate meetings, leading to a hiding-place from which she could listen to them. Thompson considers this account less as factual and more as symbolic of Agrippina's influence over the senate.[48] According to the archaeologist Pierre Gros, the sanctuary served as a model for later complexes dedicated to the imperial cult in the western Roman empire.[49]

The temple was damaged in the Great Fire of Rome of 64 CE, but restored under the emperor Domitian (r. 81–96 CE); the Portico of the Danaids, probably also destroyed in 64, may never have been rebuilt.[50] The temple was finally destroyed in another fire, during the night of 18–19 March 363.[51][g] The blaze may have destroyed the precinct as well as the temple itself:[h] the Sibylline Books, housed within the temple, were narrowly rescued from the flames. The cause of the fire was never firmly established. The emperor Julian, who was in the process of an ultimately unsuccessful effort to re-establish Roman polytheism as the empire's dominant religion, considered it an act of arson by Christians: this view has been considered plausible in modern scholarship, particularly as the Sibylline Books were viewed as a symbol of Julian's anti-Christian religious policy, but no secure evidence on the matter exists. Christian writers saw the destruction as a matter of divine intervention: the fifth-century Church historian Theodoret falsely claimed that the temple had been struck by lightning, while the theologian John Chrysostom wrote that God had destroyed the temple to punish Julian's actions.[53] The temple may have been systematically dismantled after the fire; pieces of marble from it were possibly reused in the construction of a new building, of uncertain function, on top of the ruined podium at some point in late antiquity.[54]

In the twelfth century, the philosopher John of Salisbury propagated an account that Pope Gregory I (r. 590–604) had destroyed the Library of Palatine Apollo to create more space for Christian scriptures, but his testimony is considered unreliable by modern scholarship.[55] The only surviving remains of the temple's two libraries date to reconstructions made in the Domitianic period,[56] which rebuilt the structures on higher ground.[57]

Description

[edit]Location

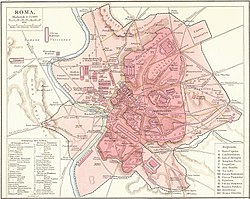

[edit]The temple was the second in Rome dedicated to Apollo; its position on the Palatine Hill made it the first within the Roman pomerium.[58] It was prominently visible from the Circus Maximus to the south of the Palatine.[59] It was adjacent to the older Temple of Cybele, which had been dedicated in 191 BCE,[60] and the ancient stairway known as the Scalae Caci ('Stairs of Cacus').[61] It was also near the early-third-century Temple of Victory; the proximity of the monuments may have been intended to reinforce the links between Apollo and the military victories for which Augustus credited him.[62]

The Temple of Apollo Palatinus was immediately south-east of a domus ('house') constructed during the late Roman Republic (c. 133–33 BCE). In the 1950s, this house was designated by one of its excavators, Gianfilippo Carettoni, as the domus Augusti ('House of Augustus'), since Carettoni believed that it had been Augustus's personal residence.[63] Following Carettoni's excavations, the temple and the house were believed to have been connected by a ramp, though this theory was disproved by later excavations. The status of the so-called domus Augusti and its relationship to both Augustus and the Temple of Apollo Palatinus is controversial. Excavations subsequent to Carettoni's indicate that the house was largely destroyed, while still under construction, to facilitate the building of the temple; they also found that the house was considerably larger than Carettoni believed, which meant that its identification as Augustus's personal residence contradicted the testimony of Roman biographers that the emperor's Palatine house had been noted for its modesty.[64]

According to Roman authors, the temple's sanctuary also included the Roma Quadrata ('Square Rome'), a monument to the foundation of the city by Romulus; a four-columned shrine known as the Tetrastylum; and the Auguratorium, a monument to the taking of the auspices by Romulus during the foundation of Rome, which may have been an alternative name for the Roma Quadrata.[38]

Architecture

[edit]

Scholars are divided on the interpretation of the temple's architecture. The archaeologist John Ward-Perkins has described its architecture and embellishment, particularly its use of proportions common in Hellenistic architecture and its sculptural programme, as "a lively architectural experiment". He contrasts this with the conservatism of other Augustan projects, such as the restoration of the Temple of Cybele, which largely reused material from the existing structure.[57] On the other hand, the archaeologist Stephan Zink describes the temple as "an imposing revival of Republican architectural traditions".[12] According to the Roman architectural writer Vitruvius, the temple's intercolumniation was diastyle (that is, the gap between each pair of columns was three times a column's width).[66] Zink interprets this wide intercolumniation, unusual in contemporary architecture but common in older Roman and Etruscan temples, as a sign of conservatism.[67] The archaeologist Barbara Kellum has suggested that the temple's intercolumniation may have specifically recalled that of the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus,[68] Rome's most important temple.[69]

The temple's precinct – the Area Apollonis – was built on a raised platform, approximately 9 metres (30 ft) above the terrace below and generally considered to have measured approximately 70 by 90 metres (230 by 300 ft),[71] which included a retaining wall with blocks of tufa.[38] This platform was constructed on top of the remains of older buildings on the site, which were demolished and their courtyards filled in.[72] The entrance to the precinct was through a triumphal arch, known as the Arcus Octavii, in honour of Augustus's father, Gaius Octavius.[73] The sculptural programme of this arch, which included a statue group by the Greek sculptor Lysias showing Apollo and Diana mounted in a chariot, has been called "a further testimony to Apollo's Augustan vocation" by the archaeologist Maria Tomei.[74]

A Roman temple generally included an enclosed inner part, known as the cella, surrounded by a series of columns (the peristyle) and approached via a porch or vestibule known as the pronaos.[75] Apart from the podium, the Temple of Apollo Palatinus was constructed entirely from marble, making it the first temple in Rome to be built in this fashion.[8] The number of columns supporting the temple is unclear; it is generally reconstructed as having had six columns across the front of the pronaos, though the archaeologist Amanda Claridge has proposed that it may instead have had four across the front and seven along its length.[76] Corinthian capitals have been found among the temple's remains;[38] the columns which supported them are reconstructed to have reached 14 metres (46 ft) in height and have supplied evidence of fluting.[77] Apart from the drums of the columns, all surviving fragments of the temple have furnished evidence of painted polychromy.[78] Parts of the column capitals were probably gilded, while other parts of the temple were painted in yellow ochre and red, blue, brown and green pigments.[79] The podium of the temple was constructed using materials and techniques common during the late Republican period, using ashlar blocks of tufa and travertine (known to the Romans as opus quadratum), under the walls and columns of the temple's cella, surrounding a core of concrete (known to the Romans as opus caementicium).[80] According to reconstructions made by the archaeologist Giuseppe Lugli, the temple had overall dimensions of 22.4 by 38.8 metres (73 by 127 ft), with a cella 26 metres (85 ft) long and a pronaos 12.8 metres (42 ft) in length.[81]

The surviving ruins do not allow a definitive reconstruction of the temple's orientation. It is generally believed to have faced south: the temple's first excavator, Pietro Rosa, proposed this orientation in 1865, on the grounds that it would have the temple face out of the hillside in a similar manner to earlier Republican hillside sanctuaries found elsewhere in Latium.[82] In 1913, the prehistorian Giovanni Pinza suggested that the temple may have faced north, which he considered a better fit with the surviving accounts of its appearance in Roman literature, but his idea was generally rejected.[83] Some modern hypotheses, such as that of Claridge, have argued for a north-facing temple on the grounds that the more substantial foundations of the temple's southern side would be more likely to support the heavier cella than the comparatively light pronaos, and that the temple's visual impact would have been greater if the façade faced north, from which direction the temple was generally accessed.[84]

The temple's building materials, such as Libyan ivory and so-called "Punic" columns, recalled Rome's military conquests and successes.[85] Its primary material was white Carrara marble from the Italian town of Luna,[38] a material frequently used in Augustan building projects: Augustus is believed to have initiated its large-scale quarrying and exploitation.[86] Fragments of marble flooring have been found during excavations of the site.[38] The columns of the Portico of the Danaids were made from yellow giallo antico marble quarried in Numidia. This is the earliest known use of giallo antico in Rome.[87]

The temple's architecture may have been designed to compete with that of the Temple of Apollo Sosianus,[15] which was reconstructed at approximately the same time.[88] The Temple of Apollo Sosianus was restored by and named for Gaius Sosius, a former supporter of Octavian's enemy Mark Antony. Augustus later tried to reduce its prominence by constructing the Theatre of Marcellus to block the view of its façade, and rebuilt the adjacent Porticus Octaviae, named after his sister Octavia, whom Antony had abandoned in favour of Cleopatra.[89]

Sculptures and artwork

[edit]

The temple contained three cult statues: one of Apollo in the "Apollo Citharoedus" ('lyre-playing Apollo') type, one of his sister Diana, and one of their mother Latona. A further statue of Apollo was situated in front of the temple. The cult statues were the work of Greek sculptors of the fourth century BCE: that of Apollo was made by Scopas.[91] On the basis of the temple's epithet Rhamnusius, it has been conjectured that the statue originally came from the Nemeseion sanctuary at Rhamnous in Attica.[37][i] Two badly-weathered fragments of colossal statuary excavated at the temple – one from a head, excavated in the temple's foundations,[7] and one from a foot – have been suggested as possible remains of the cult statue of Apollo.[93] Depictions of the statue on Roman coinage suggest that its base was decorated with anchors and the prows of ships, linking it to the naval victory at Actium, while its hands held a lyre and a libation bowl.[94] Zanker has suggested that the choice of an Apollo Citharoedus for the cult statue, offering a libation as if in expiation, contrasted with the alternative iconography of Apollo as an "avenging archer", and would have suggested the bringing of peace and of atonement for the civil war.[95]

The cult statue of Latona was by Kephisdotos the Younger, the son of the Athenian sculptor Praxiteles. That of Diana was originally sculpted by the Epidaurian artist Timotheos, but its head was remade by Avianus Evander,[38] an Athenian artist who had been taken to Rome as a prisoner in the mid-first century BCE.[96] Other statues in the temple included a representation of the chariot of the sun on the acroterion of the temple's ridge,[24] a group at the corners of the altar of four oxen made by the fifth-century Athenian sculptor Myron,[61] and another set representing the daughters of Danaus.[7] The Roman polymath Pliny the Elder, writing in the second half of the first century CE, catalogued works of Bupalus and Athenis, two Chian sculptors of the archaic period (c. 800 – c. 480 BCE), on the temple's pediments.[97] The inclusion of statues by noted Greek artists, especially of the fourth and fifth centuries BCE and the archaic period, came to be almost universal in the temples built or restored by Augustus in Rome.[15] The temple also contained a series of engraved gemstones dedicated by Augustus's nephew Marcellus.[61]

On the temple's doors, a scene depicting the killing of the children of Niobe by Apollo and Diana was rendered in ivory,[98] while the other door depicted the defeat of the Celtic attack on the Oracle of Delphi, of which Apollo was the patron god, in 281 BCE.[7] One of the marble jambs of the doors depicted a Delphic tripod[38] flanked by griffins, with an acanthus, symbolic of Apollo in his capacity as a god of regeneration, springing from it.[99] The cella was lit by a chandelier said to have been taken by Alexander the Great from the Greek city of Thebes.[100]

The Portico of the Danaids included statues of the eponymous Danaids,[103] the Egyptian sisters who killed their cousin-husbands on their wedding night in an act of impietas.[j] This artwork may have been intended to evoke and condemn the memory of Cleopatra, who had similarly married and then had assassinated her brother, Ptolemy XIV.[105] The statues of the Danaids were situated between the portico's columns, near a statue of Danaus with drawn sword and faced by equestrian statues of their bridegrooms and victims, the sons of Aegyptus.[106] Parts of at least four of these statues, around 1.2 metres (3.9 ft) in height and in the style of herms, have been discovered. Three of these were sculpted from black bigio morato marble, probably quarried in Ain El-Ksir in Tunisia or from Cape Tainaron in southern Greece,[107] while at least one was made from red rosso antico marble.[108] A series of painted terracotta panels in the Campana style, found in the area of the temple, may have originally belonged to the Portico of the Danaids.[110] The panels show mythical scenes including Perseus's defeat of Medusa, the caryatids and the contest between Hercules and Apollo for the Delphic tripod.[100][k] Kellum has interpreted the latter myth as an allegory for the military struggle between Augustus and Antony, given Augustus' identification with Apollo and Antony's similar claims of descent from and affinity with Hercules: the tripod, a traditional votive dedication of victorious generals, may also have been linked with Augustus's victory at Actium.[112] Other scenes show the Egyptian goddess Isis trapped between two sphinxes, probably alluding to the defeat of Cleopatra,[113] and human beings worshipping sacred objects. These include one which may be a candelabrum – a symbol both of Apollo and of pietas[6] – a thymiaterion or a baetylus, a cult object associated with Apollo.[114] It has been suggested that a marble sculpture known as the meta ('turning-post'), displayed in modern times in the Villa Albani, may originally have been one of several monumentalised baetyli that stood around the sanctuary.[115]

The portico's libraries included a statue of Augustus with the appearance of Apollo.[100] A statue of a young man (ephebe) in black basalt, discovered by Rosa in 1869 in the cryptoporticus to the temple's east, is believed to have come from the temple.[116] A common building material in the temple's sculptures was Pentelic marble from Mount Pentelicus near Athens: this material was frequently used in Athenian building projects of the fifth and fourth centuries BCE, and was particularly prized in Rome.[117]

Walker has suggested that the sculptural decoration of the Temple of Apollo Palatinus served a complex ideological purpose: to elevate the standard of Rome's public art, to showcase the material wealth generated by the Roman Empire's expansion, and to promote Augustan moral values such as the value of Roman citizenship and of modesty in dress and personal behaviour.[15] Between 161 and 169 CE, a further statue of the "Apollo Comaeus" ('Long-Haired Apollo') type was taken from the Persian city of Seleucia and installed in the temple by the Roman emperor Lucius Verus, following the city's capture in the Roman–Parthian War of 161–166.[118]

Function

[edit]

It is unclear whether the Temple of Apollo Palatinus was intended to supplant or complement the existing centre for Apollo's worship at the Temple of Apollo Sosianus.[119] According to the classicist Bénédicte Delignon, the temple served to establish Apollo as the tutelary deity of Rome and as a representation of Augustus's symbolic refoundation of the city.[32] In Augustus's political propaganda, it represented the restoration of Rome's 'golden age', a key aspect of Augustan ideology,[120] marked by the end of civil war and the reaffirmation of Roman pietas.[94] The visual iconography was particularly ideologically charged: though it made no direct references to Augustus, it employed several images and tropes commonly associated with him in contemporary culture.[121] The classicist Gilles Sauron has interpreted many of the temple's artworks, including that of the Danaids and the scenes on the temple's doors, as emblematic of the divine punishment of impietas.[122]

Assessments of the sanctuary's primary significance vary. Walker has described the temple as "Augustus's personal shrine",[42] a view echoed by Zanker, who considers that the adjacent house was that of Augustus, has suggested that the two buildings combined in a manner reminiscent of a Hellenistic palace-complex.[123] Pointing to the prominence of the sanctuary's libraries, the classical archaeologist Lilian Balensiefen has described the temple as a "literary sanctuary" in which Apollo was venerated in his capacity as a god of learning.[59] For Zanker, the temple was part of a cultural programme intended both to emulate and to surpass the artistic achievements of ancient Greece.[6] The temple was also used for meetings of the senate.[27]

Over time, the temple was given additional functions, likely on an ad hoc basis rather than as part of any preconceived plan.[124] From around 20 BCE,[125] the temple was used to store the Sibylline Books, a series of prophetic writings believed to date from the time of Rome's semi-legendary king Tarquinius Superbus (c. 510 BCE), which Augustus moved there from the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus. They were stored in gold cases in the base of the cult statue of Apollo.[126] The temple became a popular site for the dedication of votive offerings, particularly statues. According to Augustus's autobiography, the Res Gestae, he melted down approximately 80 silver statues of himself that had been offered there by Rome's citizens, sold the resulting metal and used the proceeds to purchase gold tripods in honour of Apollo.[100]

The temple played a significant role in the Secular Games, a religious and artistic festival revived by Augustus in 17 BCE and repeated irregularly thereafter.[127] On 3 June, the third day of the inaugural games, Augustus and his lieutenant Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa made sacrifices to Apollo and Diana at the temple.[128] The poet Horace wrote his Carmen Saeculare, a religious hymn, for the occasion: it received its first performance on the same day, sung at the temple by a choir of 27 boys and 27 girls and accompanied by sacrifices to Apollo and Diana.[130] In years where the Secular Games were held, priests known as the quindecimviri sacris faciundis, who had responsibility for the temple's Sibylline Books, met at the temple on 25 May and cast lots to determine which of them would sit on the various tribunals which distributed purifying agents – torches, sulphur and bitumen – to the Roman people. The temple was then used, alongside the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, the Temple of Diana on the Aventine and the Temple of Jupiter Tonans, to receive offerings of first fruits (fruges) and as centres for the distribution of the aforementioned purifying agents (purgamenta).[131]

Reception

[edit]

In modern times, the temple has been described by Ward-Perkins as "one of the earliest and finest of the Augustan temples".[1] It was noted by contemporaries as among Rome's most impressive monuments,[27] and described by the historians Velleius Paterculus and Josephus in the 1st century CE as the greatest of Augustus's building projects.[132] Suetonius similarly described it as among Augustus's most important architectural works, alongside the Forum of Augustus, the Temple of Mars Ultor and the Temple of Jupiter Tonans.[133] Delignon has suggested that the proem of the poet Virgil's Georgics, published in 29 BCE, may have alluded to the proposed or incipient construction of the temple.[134]

The Roman poet Propertius attended the opening of the temple and wrote two elegies to celebrate it.[30] The first of these (conventionally numbered 2.31) was written around the time of the temple's dedication and published in either 25 or 24 BCE.[135] Propertius's contemporary Horace published an ode (1.31) in 23 BCE, ostensibly written on the day of the temple's dedication to celebrate Apollo.[136] Around 20 BCE, the poet Tibullus wrote an elegy (2.5) commemorating the appointment of Marcus Valerius Messalinus as a priest of Apollo with responsibility for inspecting the Sibylline Books stored at the temple.[125]

The temple's political significance and association with Actium became universal themes of poetic responses to the monument from 16 BCE onwards, when Propertius published the second of his elegies on the temple (4.6).[137] A common motif in these poetic works was the association between the Sibylline Books and the works of the poets themselves.[138] The newly intensified religious significance of the Palatine Hill also featured in its presentation in the eighth book of Virgil's Aeneid, composed between 29 and 19 BCE, in which the king Evander walks Aeneas around the future site of the temple;[10] later in Aeneid 8, the Battle of Actium is reconstructed as a theomachic contest on the Shield of Aeneas, and Augustus's triple triumph of 29 BCE is anachronistically imagined as having taken place at the temple.[139] Many of the responses to the temple in Augustan poetry have been read as appropriating, subverting or challenging its political and ideological significance.[32] Ovid, in the Ars Amatoria (published around 4 BCE), wrote of the temple as a particularly fruitful place to find pretty women.[140] Later, in the Tristia (composed between 9 and 18 BCE), he included the temple in an imagined tour of the monuments of central Rome.[141]

The temple's cult statue of Apollo was depicted on the Sorrento Base, a late-Augustan or early-Tiberian (that is, c. 14 CE) statue plinth first identified as a depiction of it by the architectural historian Christian Hülsen in 1894.[142] Gros has suggested that a group of bronze statues found in the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum, known as "dancers" or "Danaids", were modelled after those of the Danaids from the Portico of the Danaids.[100]

Archaeological study

[edit]

In modern times, only the cement core of the temple's podium, measuring 19.2 by 37.0 by 4.7 metres (63.0 by 121.4 by 15.4 ft),[52] survives,[38] as well as isolated architectural fragments including blocks from the cella.[12] Pietro Rosa made the first full excavations of the area around the temple in the nineteenth century. He began working on the Palatine in 1861, in the employ of Napoleon III, the owner of the Farnese Gardens which included the site of the temple.[143] In 1863, he discovered the Arcus Octavii to the north of the temple,[108] followed by the concrete core of the temple's podium in 1865.[144] In the same year, he consolidated the surviving fragments of the temple and built a staircase over them.[12] In 1869 he discovered the surviving fragments of statuary in the Portico of the Danaids,[108] and he carried out his final excavations in 1870. During Rosa's excavations, the site was opened to the public on Thursdays, though visitors had to obtain a permit from the French government, and Rosa often led tours himself.[145]

Further excavations took place under Alfonso Bartoli in 1937, as part of Bartoli's extensive excavations in the Roman Forum and on the Palatine; he removed 40,000 cubic metres (52,000 cu yd) of earth to bring the whole domus Augusti complex down to its Roman level.[146] In the 1950s, Giuseppe Lugli re-surveyed and documented the surviving remains: this work was described in 2008 as the most detailed existing study of the temple's ruins, though it contains contradictions and ambiguities, particularly over the width of the column axis (that is, the distance between the centres of adjacent columns).[147]

Rosa misidentified the temple as the third-century BCE Temple of Jupiter Invictus (or Jupiter Victor), believing its location on the side of the Palatine to be reminiscent of that of other Republican-era sanctuaries.[82] The architect Henri Deglane, a member of the French School at Rome, accepted this identification in his 1885–1886 reconstruction of what he called the "Palace of the Caesars" on the Palatine Hill.[148] In 1910, Giovanni Pinza studied the concrete used in the temple and concluded that it was early Augustan in date, being similar to that used for the Mausoleum of Augustus, completed in 28 BCE.[149] The first to identify the temple as Apollo Palatinus was the nineteenth-century art historian Franz von Reber; this identification was advanced in a 1914 article by the classicist Oliffe Legh Richmond, who argued for it largely from the correspondence between the excavated remains and literary testimonia of the temple. By 1952, scholars had generally come to accept Pinza's conclusion that the temple had been constructed on top of the remains of houses constructed in the late Republican period (that is, c. 100 – c. 30 BCE), which eliminated any possibility of its being third-century in date.[150] The temple was by this time almost universally accepted as Apollo Palatinus.[151]

The area around the temple, including its sanctuary and the rest of the domus Augusti complex, was further excavated by Carettoni between 1958 and 1984.[152] The excavations of 1968 saw the excavation of the temple's pronaos as well as the beginning of the collection of the fragmentary terracotta plaques, which continued in 1969 and 1970.[100] Carettoni's excavations were only partially published.[153] The work of both Rosa and Carettoni involved extensive reconstruction, which was continued thereafter by the Soprintendenza Archeologica di Roma.[154]

Zink carried out an architectural survey of the temple from 2006, primarily aimed at reconstructing the dimensions, measurements and form of its plan and elevation.[155] In 2008, he investigated the architectural remains of the façade for the traces of its original colouring, together with the conservator and colour scientist Heinrich Piening.[156] Between 2009 and 2013, Zink also documented the architectural remains in an area south-west of the temple, revealing a building dating to the archaic period (that is, between the sixth and early fifth centuries BCE), which he posited to have been a small shrine.[157]

Footnotes

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ According to Zanker, Greek art was held to have an "acknowledged moral superiority".[6]

- ^ Previous projects, such as the construction of the Temple of Caesar, had been conducted in collaboration with others: in that case, his fellow triumvirs Antony and Lepidus.[13]

- ^ The classicists Olivier Hekster and John Rich dispute any direct connection between the victory and the temple;[25] the classicist Robert Gurval has similarly argued that it is difficult to be certain that Octavian intended for the temple to be predominantly associated with Actium.[26]

- ^ A minority view, first advanced by the architectural historian Christian Hülsen,[39] holds that the temple known from Roman literary sources as the Temple of Apollo Palatinus was in the hitherto-unexcavated area of the Vigna Barberini on the northern side of the Palatine Hill, but this suggestion is generally rejected in favour of the conventional identification.[40] In this article, references to the archaeological site and excavated remains refer to the temple near the so-called domus Augusti.

- ^ The precise relative position of the Temple of Apollo and the Portico of the Danaids is disputed: the portico is generally held either to have been situated on a terrace immediately below the temple, or to have surrounded it on its own level.[41]

- ^ The classicist David L. Thompson points out that the account of Suetonius, which provides the evidence for senate meetings in the temple precinct, is technically ambiguous as to where exactly in the sanctuary they occurred, but concludes that the portico and its libraries are the most likely answer.[46]

- ^ The archaeologist Caroline K. Quenemoen gives the date of destruction as 364 CE.[52]

- ^ The Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus, whose work is the primary source for the destruction, uses the word templum ('temple') to refer to the damaged structure, which usually referred to the entire sacred area around the main temple building (aedes).[51]

- ^ The classicist Linda Jones Roccos has argued that the statue was not in fact ancient, but rather made by an Augustan sculptor copying the style of earlier Greek statues, particularly the Athenian type known as "Apollo Patroos" ('Apollo the Ancestor').[92]

- ^ That is, a breach of pietas and so of the compact between human beings and the gods: the murder of a close relative was seen as the most extreme example of impietas.[104]

- ^ The classicist Karl Galinsky has suggested that the scene may represent the two characters reconciling after their conflict.[111]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Ward-Perkins 1981, p. 36.

- ^ Hill 1962, pp. 125–126. For the origins of Apollo's worship in Rome, see Jannot 2005, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Zanker 1990, p. 52.

- ^ Ward-Perkins 1981, p. 21; Suetonius records the remark at Divus Augustus 28.3

- ^ Ward-Perkins 1981, p. 37. Augustus made the claim in Res Gestae 20.4.

- ^ a b c Zanker 1990, p. 89.

- ^ a b c d e Walker 2000, p. 61.

- ^ a b Tuck 2021, p. 140.

- ^ Coarelli 2014, p. 132.

- ^ a b Schmitzer 1999.

- ^ Roccos 1989, p. 571.

- ^ a b c d Zink 2008, p. 47.

- ^ Claridge 2010, p. 100.

- ^ Welch 2005, p. 134.

- ^ a b c d Walker 2000, p. 71.

- ^ Sumi 2015, p. 218.

- ^ Feeney 2006, p. 468; Zanker 1990, p. 57.

- ^ Wiseman 2022, p. 10.

- ^ Hill 1962, p. 129. Suetonius records the story at Divus Augustus 94.4.

- ^ Zanker 1990, p. 49.

- ^ Favro 2007, p. 238.

- ^ Gardner 2013, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Hekster & Rich 2006, p. 152.

- ^ a b Gros 1993, p. 54.

- ^ Hekster & Rich 2006, pp. 154–155.

- ^ Gurval 1995, chapter 2, discussed in Clauss 1996.

- ^ a b c Morgan 2022, p. 144.

- ^ Hekster & Rich 2006; Galinsky 1996.

- ^ Hekster & Rich 2006, pp. 152, 158; Walker 2000, p. 62. The Roman historian Cassius Dio reports the omen at 49.15.5.

- ^ a b Walker 2000, p. 61; Roccos 1989, p. 571.

- ^ Galinsky 1996, p. 214.

- ^ a b c Delignon 2023, p. 115.

- ^ Hekster & Rich 2006, p. 153.

- ^ Wiseman 2022, p. 29.

- ^ Hekster & Rich 2006, p. 155.

- ^ Kajava 2022, pp. 7–12.

- ^ a b Hill 1962, p. 129; Richardson 1992, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Coarelli 2014, p. 143.

- ^ Platner & Ashby 1929, p. 18.

- ^ Quenemoen 2006, p. 229; Richardson 1992, p. 14.

- ^ Galinsky 1996, p. 219; Quenemoen 2006.

- ^ a b c Walker 2000, p. 62.

- ^ Platner & Ashby 1929, p. 84; Schmitzer 1999; Rohmann 2016, p. 242.

- ^ Galinsky 1996, p. 218.

- ^ Thompson 1981, p. 339.

- ^ Thompson 1981, pp. 338–339.

- ^ Thompson 1981, p. 339; see also Tomei 2000, p. 573.

- ^ Thompson 1981, p. 339. Tacitus recounts this episode at Annals 13.5

- ^ Gros 1993, p. 56.

- ^ Hill 1962, p. 130; Gros 1993, p. 56.

- ^ a b Rohmann 2016, p. 242.

- ^ a b Quenemoen 2006, p. 234.

- ^ Rohmann 2016, pp. 242–243.

- ^ Claridge 2014, pp. 133, 136.

- ^ Rohmann 2016, p. 243.

- ^ Fischer 2021, pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b Ward-Perkins 1981, p. 37.

- ^ Hill 1962, p. 126.

- ^ a b Fischer 2021, p. 85.

- ^ Price 1996, p. 832.

- ^ a b c Richardson 1992, p. 14.

- ^ Tuck 2021, p. 140. For the date of the Temple of Victory, see Ando 2013, p. 278.

- ^ Wiseman 2013, p. 255.

- ^ Wiseman 2013, p. 255, citing Iacopi & Tendone 2006; see also Claridge 2014, p. 129.

- ^ Quenemoen 2006, p. 231.

- ^ Wiseman 2022, p. 29, citing Vitruvius, De Architectura 3.3.4.

- ^ Zink 2008, p. 63.

- ^ Kellum 1993, p. 76.

- ^ Coarelli 2014, p. 32.

- ^ Quenemoen 2006, p. 236.

- ^ Gros 1993, p. 56; Quenemoen 2006, p. 232. Quenemoen suggests alternative dimensions of 40 by 25 metres (131 by 82 ft).[70]

- ^ Zink 2015, p. 369.

- ^ Hill 1962, p. 130.

- ^ Tomei 2000, p. 560.

- ^ Stamper 2015, p. 174.

- ^ Claridge 2014, p. 141; Wiseman 2022, p. 28.

- ^ Gros 1993, p. 55: for fluting, Zink 2008, p. 51.

- ^ Zink & Piening 2009, p. 110.

- ^ Zink & Piening 2009, p. 113.

- ^ Quenemoen 2006, p. 234; Zink 2008, p. 48.

- ^ Quenemoen 2006, p. 234, citing Lugli 1965, pp. 266–267.

- ^ a b Claridge 2014, p. 128.

- ^ Claridge 2014, p. 129; Wiseman 2022.

- ^ Claridge 2010; Claridge 2014, pp. 138–141; Wiseman 2022, p. 29.

- ^ Walker 2000, p. 61. The Punic columns quotation is from Propertius, Elegies 2.31, and recalls the Punic Wars in which Rome defeated the city of Carthage.

- ^ Ward-Perkins 1981, p. 22.

- ^ Walker 2000, p. 72, note 2; Ward-Perkins 1981, p. 36.

- ^ Walker 2000, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Walker 2000, p. 63.

- ^ Hill 1962, p. 132.

- ^ Coarelli 2014, p. 143; Guerrini 1958, p. 936.

- ^ Roccos 1989, p. 587.

- ^ Roccos 1989, p. 579.

- ^ a b Delignon 2023, p. 116.

- ^ Zanker 1990, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Guerrini 1958, p. 936.

- ^ Walker 2000, p. 61, citing Pliny, Natural History 36.13.

- ^ Wiseman 2013, p. 250.

- ^ Zink & Piening 2009, p. 114. For the association between Apollo and the acanthus, see Pollini 2012, p. 292.

- ^ a b c d e f Gros 1993, p. 55.

- ^ Quenemoen 2006, p. 229; Tomei 1997, p. 56.

- ^ Sheard 2022, p. 52, citing Candilio 1989, pp. 86, 88.

- ^ Walker 2000, p. 61, with reference to Propertius, Elegies 2.31.

- ^ Potter & Mattingly 1999, p. 126.

- ^ Delignon 2023, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Richardson 1992, p. 14. For the statue of Danaus, see Gros 1993, p. 55.

- ^ Cook 2018, p. 283.

- ^ a b c Quenemoen 2006, p. 229.

- ^ Tuck 2021, pp. 141–142.

- ^ Coarelli 2014, p. 114. Tuck places them as "lining" the inside of the portico.[109]

- ^ Galinsky 1996, p. 223.

- ^ Kellum 1993, pp. 77–78: see also Tuck 2021, p. 142.

- ^ Kellum 1993, p. 78.

- ^ Gros 1993, p. 55. For the association between the baetylus and Apollo, see Zanker 1990, p. 89.

- ^ Zanker 1990, p. 89; Longfellow 2010, p. 281.

- ^ Tomei 1997, p. 60; Coarelli 2014, p. 157.

- ^ Giustini et al. 2018, p. 252 (on the use of Pentelic marble in the Temple of Apollo Palatinus); Bernard 2010, pp. 49–50 (on the status of Pentelic marble in Rome).

- ^ Hill 1962, p. 132; Harper 2021, p. 16.

- ^ Miller 2006.

- ^ Delignon 2023, p. 116; Sauron 1994, p. 501.

- ^ Zanker 1990, p. 195.

- ^ Delignon 2023, p. 117.

- ^ Wiseman 2022, p. 12, citing Zanker 1983, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Galinsky 1996, p. 213.

- ^ a b Delignon 2023, p. 126.

- ^ Coarelli 2014, p. 143, citing Suetonius, Divus Augustus 31.3.

- ^ Turcan 2013, p. 83.

- ^ Galinsky 1996, p. 218; Wiseman 2012, p. 374.

- ^ Zanker 1990, p. 169.

- ^ Wiseman 2012, p. 374; Cooley 2023, p. 277. For the position of the choir and sacrifices within the Secular Games, see Zanker 1990, p. 169. Zanker gives the choir as three choruses, each composed of seven boys and seven girls.[129]

- ^ Forsythe 2012, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Platner & Ashby 1929, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Babcock 1967, p. 189. Suetonius, at Divus Augustus 29.1–3, uses the phrase vel praecipua (lit. 'among the foremost').

- ^ Delignon 2023, p. 132.

- ^ Delignon 2023, p. 118.

- ^ Delignon 2023, pp. 120–122.

- ^ Delignon 2023, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Fischer 2021, p. 90.

- ^ Delignon 2023, p. 129.

- ^ Walker 2000, p. 62; Ars Amatoria 3.379–389.

- ^ Delignon 2023, pp. 124–125; Tristia 3.1. For the dates of the Tristia and Ars Amatoria, see Thorsen 2013, p. 381.

- ^ Roccos 1989, pp. 573–574.

- ^ Cooley 2006, p. 207.

- ^ Wiseman 2022, p. 11.

- ^ Cooley 2006, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Lugli 1946, p. 6; Carettoni 1960, p. 193; Coarelli 2014, p. 142.

- ^ Zink 2008, p. 49; for Lugli's survey, see Claridge 2014, p. 129.

- ^ Claridge 2014, p. 129.

- ^ Claridge 2014, p. 129, n. 11.

- ^ Coarelli 2014, p. 143; Hill 1962, p. 131; Claridge 2014, p. 129. Richmond's article is Richmond 1914.

- ^ Bishop 1956, p. 187.

- ^ Wiseman 2022, p. 11; Zink 2015, p. 359.

- ^ Hekster & Rich 2006, p. 149. The published reports are Carettoni 1967 and Carettoni 1978.

- ^ Zink 2012, p. 390.

- ^ Zink 2012, p. 389.

- ^ Zink & Piening 2009, p. 109.

- ^ Zink 2015, pp. 359–360, 362.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ando, Clifford (2013) [2000]. Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-28016-8.

- Babcock, Charles L. (1967). "Horace Carm. 1. 32 and the Dedication of the Temple of Apollo Palatinus". Classical Philology. 62 (3): 189–194. doi:10.1086/365257. JSTOR 268380. S2CID 162618366.

- Bernard, Seth (2010). "Pentelic Marble in Architecture at Rome and the Republican Marble Trade". Journal of Roman Archaeology. 23 (1): 35–54. doi:10.1017/S1047759400002294. S2CID 193225834.

- Bishop, J. H. (1956). "Palatine Apollo". The Classical Quarterly. 6 (3/4): 187–192. doi:10.1017/S0009838800020140. JSTOR 636910. S2CID 246881093.

- Candilio, Daniela (1989). "Nero Antico". In Anderson, Maxwell L.; Nista, Leila (eds.). Radiance in Stone: Sculptures in Colored Marble from the Museo Nazionale Romano. Rome: De Luca Edizioni d’Arte. pp. 85–93. ISBN 978-0-9638169-4-8.

- Carettoni, Gianfilippo (1960). "Excavations and Discoveries in the Forum Romanum and on the Palatine during the Last Fifty Years". The Journal of Roman Studies. 50: 192–203. doi:10.2307/298300. JSTOR 298300. S2CID 162627129.

- Carettoni, Gianfilippo (1967). "I problemi della zona augustea del Palatino alla luce dei recenti scavi" [The Problems of the Augustan Zone of the Palatine in the Light of the Recent Excavations]. Atti della Pontificia Accademia Romana di Archeologia (Serie In) (in Italian). 39: 55–65.

- Carettoni, Gianfilippo (1978). "Roma — Le costruzioni di Augusto e il tempio di Apollo sul Palatino" [Rome — The Buildings of Augustus and the Temple of Apollo on the Palatine]. Archeologia Laziale (in Italian). 1: 72–74.

- Claridge, Amanda (2010) [1998]. Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954683-1.

- Claridge, Amanda (2014). "Reconstructing the Temple of Apollo on the Palatine Hill in Rome". In Häuber, Chrystina; Schütz, Franz X.; Winder, Gordon M. (eds.). Reconstruction and the Historic City, Rome and Abroad: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Munich: Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität. pp. 128–152. ISBN 978-3-931349-41-7.

- Clauss, Jerome (7 September 1996). "Actium and Augustus". Bryn Mawr Classical Review. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- Coarelli, Filippo (2014). Rome and Environs: An Archaeological Guide. Translated by Clauss, James J.; Harmon, Daniel P. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-28209-4. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- Cook, Emily Margaret (2018). Legacies of Matter: The Reception and Remediation of Material Traditions in Roman Sculpture (PDF) (Ph.D.). Columbia University. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- Cooley, Alison (2006). "(M.A.) Tomei Scavi francesi sul Palatino. Le indagini di Pietro Rosa per Napoleone III. (Roma Antica vol. 5.) Pp. xlvi 555, gs, b/w and colour ills. Rome: École Française de Rome and Soprintendenza Archeologica di Roma, 1999. Cased, €152. ISBN: 2-7283-0604-4". The Classical Review. 56 (1): 207–208. doi:10.1017/S0009840X05001083. S2CID 231895519.

- Cooley, M.G.L. (2023) [2008]. Cooley, M. G. L. (ed.). The Age of Augustus. Lactor Sourcebooks in Ancient History. Vol. 17 (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781009382885. ISBN 978-1-009-38289-2.

- Delignon, Bénédicte (2023). "Cultural Memory, from Monument to Poem: The Case of the Temple of Apollo Palatinus in the Augustan Poets". In Dinter, Martin T.; Guérin, Charles (eds.). Cultural Memory in Republican and Augustan Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 115–134. doi:10.1017/9781009327749.007. ISBN 978-1-009-32774-9.

- Favro, Diane (2007) [2005]. "Making Rome a World City". In Galinsky, Karl (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Augustus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 234–263. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521807964. ISBN 978-1-139-00083-3.

- Feeney, Denis (2006) [1992]. "Si licet et fas est: Ovid's Fasti and the Problem of Free Speech under the Principate". In Knox, Peter E. (ed.). Oxford Readings in Ovid. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 464–488. ISBN 978-0-19-928115-2.

- Fischer, Jens (2021). "Vates Apollinis, vates Augusti - Das Verhältnis des palatinischen Apollonheiligtums zu Orakeln und sein Einfluss auf das Selbstverständnis der zeitgenössischen Dichter" [Vates Apollinis, vates Augusti – The Relation of the Palatine Sanctuary of Apollo to Oracles, and its Influence on the Self-Image of Contemporary Poets]. Graeco-Latina Brunensia (in German). 26 (2): 83–98. doi:10.5817/GLB2021-2-6.

- Forsythe, Gary (2012). Time in Roman Religion: One Thousand Years of Religious History. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-31441-4.

- Galinsky, Karl (1996). Augustan Culture: An Interpretative Introduction. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05890-0.

- Gardner, Hunter H. (2013). Gendering Time in Augustan Love Elegy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-965239-6.

- Giustini, Francesca; Brilli, Mauro; Gallocchio, Enrico; Pensabene, Patrizio (2018). "Characterisation of White Marble Objects from the Temple of Apollo and the House of Augustus (Palatine Hill, Rome)". In Matetić Poljak, D.; Marasović, K. (eds.). Asmosia XI, Proceedings of the International Conference of ASMOSIA (18–22 May 2015). Split: University of Split. pp. 247–253. ISBN 978-953-6617-49-4.

- Gros, Pierre (1993). "Apollo Palatinus". In Steinby, Eva Margareta (ed.). Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae (in French). Vol. 1. Rome: Edizioni Quazar. pp. 54–57. ISBN 978-88-7097-019-7.

- Guerrini, Lucia (1958). "Avianus Evander". Enciclopedia dell'arte antica, classica e orientale [Encyclopaedia of Ancient, Classical and Oriental Art] (in Italian). Vol. 1. Rome: Treccani. p. 936. OCLC 559022.

- Gurval, Robert Alan (1995). Actium and Augustus: The Politics and Emotions of Civil War. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08489-0.

- Harper, Kyle (2021). "Germs and Empire: The Agency of the Microscopic". In Flower, Harriet I. (ed.). Empire and Religion in the Roman World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 13–34. doi:10.1017/9781108932981. ISBN 978-1-108-83192-5. S2CID 242690912.

- Hekster, Olivier; Rich, John (2006). "Octavian and the Thunderbolt: the Temple of Apollo Palatinus and Roman Traditions of Temple Building". The Classical Quarterly. 56 (1): 149–168. doi:10.1017/S0009838806000127. hdl:2066/42841. JSTOR 4493394. S2CID 170382655.

- Hill, Philip V. (1962). "The Temples and Statues of Apollo in Rome". The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Royal Numismatic Society. 2: 125–142. JSTOR 42662641.

- Iacopi, Irene; Tendone, Giovanna (2006). "Bibliotheca e Porticus ad Apollinis". Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Römische Abteilung (in Italian). 112: 351–378.

- Jannot, Jean-René (2005) [1998]. Religion in Ancient Etruria. Translated by Whitehead, Jane K. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-20844-8.

- Kajava, Mika (2022). Naming Gods: An Onomastic Study of Divine Epithets Derived from Roman Anthroponyms. Commentationes Humanarum Litterarum. Vol. 144. Helsinki: Grano Oy. doi:10.54572/ssc.235. hdl:10138/352341. ISBN 978-951-653-491-9. S2CID 255938487. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- Kellum, Barbara (1993) [1985]. "Sculptural Programs and Propaganda in Augustan Rome: The Temple of Apollo on the Palatine". In D'Ambra, Eve (ed.). Roman Art in Context: An Anthology. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. pp. 75–83. ISBN 978-0-13-781808-2.

- Longfellow, Brenda (2010). "Reflections of Imperialism: The Meta Sudans in Rome and the Provinces". Art Bulletin. 92 (4): 275–292. doi:10.1080/00043079.2010.10786114. JSTOR 29546132. S2CID 162304337.

- Lugli, Giuseppe (1946). "Recent Archaeological Discoveries in Rome and Italy". The Journal of Roman Studies. 36: 1–17. doi:10.2307/298037. JSTOR 298037. S2CID 161379359.

- Lugli, Giuseppe (1965) [1953]. "II tempio di Apollo Aziaco e il gruppo augusteo sul Palatino" [The Temple of Apollo Aziacus and the Augustan Group on the Palatine]. Studi Minori di Topographia Antica [Minor Studies on Ancient Topography] (in Italian). Rome: De Luca. pp. 258–290. OCLC 3004645.

- Miller, John F. (2006). "Apollo Medicus in the Augustan Age". Classical Association of the Middle West and South. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- Morgan, Harry (2022). Music, Politics and Society in Ancient Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781009232326. ISBN 978-1-009-23232-6. S2CID 253905424.

- Platner, Samuel Ball; Ashby, Thomas (1929). A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925649-5. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- Pollini, John (2012). From Republic to Empire: Rhetoric, Religion, and Power in the Visual Culture of Ancient Rome. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-8816-4.

- Potter, David Stone; Mattingly, David (1999). Life, Death, and Entertainment in the Roman Empire. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08568-2.

- Price, S. R. F. (1996). "The Place of Religion: Rome in the Early Empire". In Bowman, Alan K.; Champlin, Edward; Lintott, Andrew (eds.). The Augustan Empire, 43 BC–AD 69. The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 10 (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 812–847. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521264303. ISBN 9781139054386.

- Quenemoen, Caroline K. (2006). "The Portico of the Danaids: A New Reconstruction". American Journal of Archaeology. 110 (2): 229–250. doi:10.3764/aja.110.2.229. JSTOR 40027153. S2CID 191346680.

- Richardson, Lawrence (1992). A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-4300-6. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- Richmond, Oliffe Legh (1914). "The Augustan Palatium". Journal of Roman Studies. 4 (2): 193–226. doi:10.2307/295823. JSTOR 295823. S2CID 162477839.

- Roccos, Linda Jones (1989). "Apollo Palatinus: The Augustan Apollo on the Sorrento Base". American Journal of Archaeology. 93 (4): 571–588. doi:10.2307/505329. JSTOR 505329. S2CID 193088867.

- Rohmann, Dirk (2016). Christianity, Book-Burning and Censorship in Late Antiquity: Studies in Text Transmission. Berlin: De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-048607-0.

- Sauron, Gilles (1994). Qvis Devm? L'expression plastique des idéologies politiques et religieuses à Rome à la fin de la République et au début du Principat [Quis Deum? The Sculptural Expression of Political and Religious Ideologies in Rome at the End of the Republic and the Beginning of the Principate]. Bibliothèque des écoles françaises d'Athènes et de Rome (in French). Vol. 285. Rome: French School at Rome. doi:10.3406/befar.1994.1254. ISBN 2-7283-0313-4.

- Schmitzer, Ulrich (1999). "Guiding Strangers through Rome – Plautus, Propertius, Vergil, Ovid, Ammianus Marcellinus, and Petrarch". Electronic Antiquity. 5 (2). ISSN 1320-3606. Archived from the original on 26 April 2023. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- Sheard, Sarah Rachel Caroline (2022). The Female Body in Roman Visual Culture (Ph.D.). University of Cambridge. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- Stamper, John W. (2015). "Cella". In Orlin, Eric; Fried, Lisbeth S.; Knust, Jennifer Wright; Satlow, Michael L.; Pregill, Michael E. (eds.). The Routledge Encyclopedia of Ancient Mediterranean Religions. New York and London: Routledge. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-134-62552-9.

- Sumi, Geoffrey (2015) [2005]. Ceremony and Power: Performing Politics in Rome Between Republic and Empire. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-03666-0.

- Thompson, David L. (1981). "The Meetings of the Roman Senate on the Palatine". American Journal of Archaeology. 85 (3): 335–339. doi:10.2307/504178. JSTOR 504178. S2CID 192937640.

- Thorsen, Thea S., ed. (2013). The Cambridge Companion to Latin Love Elegy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CCO9781139028288. ISBN 978-1-107-51174-3. S2CID 160589435.

- Tomei, Maria Antonietta (1997). Museo Palatino (in Italian). Milan: Electa. ISBN 88-435-6324-6.

- Tomei, Maria Antonietta (2000). "I resti dell'arco di Ottavio sul Palatino e il portico delle Danaidi" [The Remains of the Arch of Octavius on the Palatine and the Portico of the Danaids]. Mélanges de l'école française de Rome (in Italian). 122 (2): 557–610. doi:10.3406/mefr.2000.9537. Retrieved 8 October 2023.

- Tuck, Steven L. (2021) [2015]. A History of Roman Art (2nd ed.). Hoboken: Wiley. ISBN 978-1-119-65328-8.

- Turcan, Robert (2013) [1998]. The Gods of Ancient Rome: Religion in Everyday Life from Archaic to Imperial Times. Translated by Nevill, Antonia. New York: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 9781136058509.

- Walker, Susan (2000). "The Moral Museum: Augustus and the City of Rome". In Coulston, Jon; Dodge, Hazel (eds.). Ancient Rome: The Archaeology of the Eternal City. Oxford: Oxford University School of Archaeology. pp. 61–75. ISBN 978-0-947816-55-1.

- Ward-Perkins, John Bryan (1981). Roman Imperial Architecture. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05292-3. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- Welch, Tara S. (2005). The Elegiac Cityscape: Propertius and the Meaning of Roman Monuments. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8142-1009-3.

- Wiseman, T. P. (2012). "A Debate on the Temple of Apollo Palatinus: Roma Quadrata, Archaic Huts, the House of Augustus, and the Orientation of Palatine Apollo". Journal of Roman Archaeology. 25: 371–387. doi:10.1017/S1047759400001252. ISSN 2331-5709. S2CID 192155842.

- Wiseman, T. P. (2013). "Review: The Palatine, from Evander to Elagabalus". Journal of Roman Studies. 103: 234–268. doi:10.1017/S0075435813000117. ISSN 1753-528X. JSTOR 43286787. S2CID 163022927.

- Wiseman, T. P. (2022). "Palace-Sanctuary or Pavilion? Augustus' House and the Limits of Archaeology". Papers of the British School at Rome. 90: 9–34. doi:10.1017/S0068246221000295. S2CID 246725531.

- Zanker, Paul (1983). "Der Apollontempel auf dem Palatin: Ausstattung und politische Sinnbezüge nach der Schlacht von Actium" [The Temple of Apollo on the Palatine: Furnishings and Political Significance after the Battle of Actium]. Città e architettura nella Roma imperiale (Analecta Romana Instituti Danici Supplementi) (in German). 10: 21–40.

- Zanker, Paul (1990) [1988]. The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus. Translated by Shapiro, Alan. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08124-0.

- Zink, Stephan; Piening, Heinrich (2009). "Haec aurea templa: The Palatine Temple of Apollo and its Polychromy". Journal of Roman Archaeology. 22: 109–122. doi:10.1017/S1047759400020614. S2CID 190723108.

- Zink, Stephan (2008). "Reconstructing the Palatine Temple of Apollo: A Case Study in Early Augustan Temple Design". Journal of Roman Archaeology. 21: 47–63. doi:10.1017/S1047759400004372. S2CID 194951253.

- Zink, Stephan (2012). "Old and New Archaeological Evidence for the Plan of the Palatine Temple of Apollo". Journal of Roman Archaeology. 25: 389–402. doi:10.1017/S1047759400001264. hdl:20.500.11850/422855. S2CID 194963325.

- Zink, Stephan (2015). "The Palatine Sanctuary of Apollo: The Site and its Development, 6th to 1st c. B.C." (PDF). Journal of Roman Archaeology. 28: 358–370. doi:10.1017/S1047759415002524. hdl:20.500.11850/106901. S2CID 190832524.

External links

[edit] Media related to Temple of Apollo Palatinus (Rome) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Temple of Apollo Palatinus (Rome) at Wikimedia Commons- Images and bibliography

| Preceded by Temple of Antoninus and Faustina |

Landmarks of Rome Temple of Apollo Palatinus |

Succeeded by Temple of Apollo Sosianus |