Steamed curry

| |

| Type | Curry |

|---|---|

| Place of origin | Southeast Asia |

| Region or state | Southeast Asia |

| Associated cuisine | Cambodian, Lao and Thai |

| Main ingredients | Curry paste, coconut cream/coconut milk, eggs |

| Variations | Fish amok |

Steamed curry is a type of Southeast Asian curry that is traditionally cooked by steaming or roasting (on an embers)[1] in banana leaves and served with cooked rice. The curry base is typically made with a paste, either curry paste or fish paste, and may also include coconut cream or coconut milk and eggs. A variety of leaves and staple ingredients are often added to enhance the flavor of the dish.

Etymology

In Thai, the term ho mok /hɔ̀ɔmòg/ (Thai: ห่อหมก lit. 'bury wrap'),[2] meaning "a Thai dish consisting of steamed fish or chicken in coconut cream and chili sauce,"[3] is a noun classifier and a compound word formed by two Tai words: ho + mok.[4]

- The term ho /hɔ̀ɔ̄/ is cognate with Northern Thai, Shan, and Kam-Tai, and it means "package, things wrapped in packages, to wrap, package."[5]

- The term mok /mɔk1/ is cognate with Northern Thai, Laos, and Kam-Tai means "to cover, conceal, or hide."[6][7]

In Khmer, the term amok /amŏk/ (Khmer: អាម៉ុក) is a Khmer loanword[8] that was borrowed from the old Malaysian spelling and pronunciation (amok ← amuk, amok),[9] and the Malay word amok means "irrational behavior"[10] or "someone in the grip of uncontrollable bloodlust."[11]

Some foreign authors have claimed that the term amok means "to steam in banana leaves."[12] However, according to the Khmer Dictionary (1967) version by Samdech Porthinhean Chuon Nath, this is not a proper definition and should not be confused with the actual meaning of the term.[13]

History

Thailand

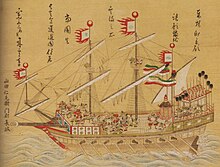

Evidence suggests that steamed curry, also known as ho mok, has been a part of Thai cuisine since the Ayutthaya period. During the reign of King Songtham, trade between Siam and Japan flourished, leading to several missions from the Ayutthaya Royal Court to Edo, the capital of Japan.[14] This resulted in a cultural exchange between the two countries. In the 17th century, the Japanese Chihara Gorohachi's works observed that Siam was a prosperous country, strategically located in the South Seas, making it a popular destination for foreign merchant ships. Japanese merchants also frequently visited Siam for business purposes.[14] One such Japanese nobleman, Ok-ya Senaphimuk (Yamada Nagamasa), who remained in Siam until 1630, brought steamed curry (ho mok) from Siam to Japan when he travelled to Nagasaki in 1624 during the Kan'ei era (1624–44).[15]

There were some restaurants in Osaka, Japan in the past that offered a menu item called homoku, and claimed that it was a dish introduced by Siam hundreds of years ago.[16]

In Thai literature, Khun Chang Khun Phaen, a verse describing steamed curry in stanza no. 8 reads:

ทำน้ำยาแกงขมต้มแกง ผ่าฟักจักแฟงพะแนงไก่ |

To prepare curry sauce for rice noodles, to slice wax gourd into the Phanaeng curry chicken, sometimes to prepare a steamed curry (ho mok), boiled eggs, fried dried fish, and Buaan curry. |

In Thai literature, Phra Aphai Mani, composed between 1821 and 1845 by Thai poet Sunthorn Phu, includes vivid descriptions of traditional Thai cuisine, which can be divided into 11 categories. One notable dish mentioned in the poem is steamed curry (ho mok) when Phra Aphai Mani performs the funeral ceremony for Thao Suthat. Phra Aphai Mani and Nang Suwanna Mali also prepare the following foods for Phra Haschai:[18]

พระซักถามนามกับข้าวแกล้งเซ้าซี้ นางทูลชี้ถวายพลางต่างต่างกัน |

Phra Aphai Mani inquired about the food in a demanding manner, prompting his daughters, Nang Soi Suwan and Nang Chan Suda, to inform him that a diverse selection had been prepared. This included dishes such as Phanang curry chicken, red curry, sliced duck meat, steamed curry, grilled fish cake, roast pork, Kaeng som, ginger syrup, deep fried shrimp cake, steamed meat dumplings (chang lon), and Buaan curry beef. |

Both Thai literature, the Phra Malethethai version by a Siamese poet Khun Suwan and the Nirat Malethethai by King Mongkut (1851–68), composed during the Rattanakosin Era, also mention a town named Ho Mok Sub-district. This sub-district is currently located in Bang Sai District, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya Province, Thailand.[20]: 78

Sombat Phlainoi, the Thai National Artist in Literature (2010), said:

Both steamed curry (ho mok) and fish fritter (pla hed) are likely to be ancient Ayutthaya dishes because there is a sub-district called Tambon Hor Mok in Bang Sai District, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya Province. We have not yet had the opportunity to investigate the history of steamed curry dishes, but it is tempting to guess that it is probably a renowned place for making steamed curry.[20]: 80

Northern Thai people of Lan Na also refer to the steamed curry dish as ho nueng (Thai: ห่อนึ่ง, ห่อหนึ้ง),[21] and the dish is also used as part of offerings to gods and spirits from the ancient period which is similar to the Canang sari.

One Thai dish that is similar to steamed curry (ho mok) is steamed meat dumplings, known locally as chang lon or chab lag.[18] This dish can be found in the provinces of Rayong and Chonburi, Thailand. It has a flavor reminiscent of a combination of steamed curry (ho mok) and fried fish cakes (thod man), but it is prepared differently by skewering the dumplings and grilling them until they are dry and then roasting them with coconut milk.[18]

Steamed curries hold not only a special place in Thai cuisine but also carry significant cultural significance. In fact, there are idioms in Thai that revolve around this dish. For instance, the phrase oe-o-ho-mok (Thai: เออออห่อหมก) is used to express agreement or approval. However, there is also a satirical verse, sak-ka-wa-duean-ngai-khai-ho-mok (Thai: สักวาเดือนหงายขายห่อหมก), which uses the term khai ho mok[20]: 108 to mock prostitutes of the past who would roam around local casinos and at the Saphan Lek in Bangkok, earning money through sex work.[22] This dish highlights the enduring relationship between the steamed curry dish (ho mok) and the cultural practices in Thai society, dating back to ancient times. The use of aromatic herbs and spices in the dish emphasizes the importance of natural ingredients in Thai cuisine, which is deeply rooted in the country's agricultural heritage.

Ingredients

Steamed curry is a dish that typically includes a curry paste or fish paste as the main ingredient. Along with the paste, a variety of leaves and staple components are added to the dish, such as fish, crab, prawn, bamboo shoots, chicken, snail, tofu, and algae. The specific ingredients used may vary depending on the region, with different Southeast Asian countries having their own unique versions of steamed curry.

Variations

There are various types of steamed curry dishes found in different countries, each with their own unique names. Some examples include steamed fish curry.

Cambodia

Cambodian cuisine is known for its use of a flavorful curry paste called kroeung (Khmer: គ្រឿង) for preparing a steamed curry dish.

- Steamed fish curry: Amok trei (Khmer: អាម៉ុកត្រី).

- Steamed chicken curry: Amok sach moan (Khmer: អាម៉ុកសាច់មាន់).

- Steamed Asian green mussel curry: Amok khyang[23] (Khmer: អាម៉ុកខ្យង).

- Steamed tofu curry: Amok tauhu (Khmer: អាម៉ុកតៅហ៊ូ).

India

Laos

Steamed curry dishes are a part of Laos cuisine, often prepared by roasting them over hot embers.[25]

- Steamed fish curry: Mok pa (Lao: ໝົກປາ).

- Steamed bamboo shoot curry: Mok naw mai[26] (Lao: ໝົກໜ່ຳໄມ້).

- Steamed chicken curry: Mok Kai (Lao: ໝົກໄກ່).

- Steamed algae (Mekong weed) curry: Mok khai (Lao: ໝົກໄຄ).

Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia

- Steamed fish curry: Otak-otak, Sata (Malaysian state of Terengganu).

- Steamed carp curry: Pepes (Indonesia).

Myanmar

- Steamed fish in banana leaf (marinated with spices): Ngàbàundou[27]

Dai in Kengtung, Shan State

- Steamed curry: Ho nung pla[28]

- Steamed curry: Pag jog[29]

Philippines

- Steamed tuna meat curry: Utak-utak (Tausūg).

Thailand

Curry paste, also known as prik kaeng (Thai: พริกแกง) in Thai cuisine, is an essential ingredient for preparing steamed curry dishes.

- Steamed fish curry: Ho mok pla, Mok pla (Isan) (Thai: ห่อหมกปลา, หมกปลา).

- Steamed bamboo shoot curry: Ho mok nor mai, Mok nor mai (Isan) (Thai: ห่อหมกหน่อไม้, หมกหน่อไม้).

- Steamed chicken curry: Ho mok kai, Mok kai (Isan) (Thai: ห่อหมกไก่, หมกไก่).

- Steamed Asian green mussel curry: Ho mok hoy ma laeng phu (Thai: ห่อหมกหอยแมลงภู่).

- Steamed clown knifefish curry: Ho mok pla grai (Thai: ห่อหมกปลากราย).

- Steamed tofu curry: Ho mok tauhu, Mok tauhu (Isan) (Thai: ห่อหมกเต้าหู้).

Xishuangbanna Dai Autonomous Prefecture

- Dai Banana leaf fish (steamed or grilled with paste): Xianjiao ye kao yu[30] (Chinese: 香蕉叶烤鱼) or Ho nung pla[31]

Gallery

-

Laotian steamed fish curry (mok pa)

-

Thai steamed seafood curry (ho mok thale) served in a coconut

See also

- Otak-otak, similar fish dumpling, a Nyonya Peranakan cuisine common in Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia

- Pepes, Indonesian dish cooking method by wrapping in banana leafs

- Botok, similar Indonesian Javanese dish wrapped in banana leaf

References

- ^ Ken Albala, ed. (2011). Food Cultures of the World Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-313-37627-6.

- ^ Lees, Phil (May 25, 2007). "The Dish: Fish Amok". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

The origins of fish amok are a source of regional debate. Dishes of this kind aren't unique to Cambodia. Malaysia and Indonesia boast the similar otak otak and Thailand cooks a spicier hor mok but neither nation embraces them with the passion of Cambodia. "Amok" in the Cambodian language, Khmer, only refers to the dish whereas in Thai, "hor mok" translates as "bury wrap," suggesting amok may have come from Cambodia's neighbor.

- ^ Haas, Mary Rosamond; Grekoff, George V.; Mendiones, Ruchira C.; Buddhari, Waiwit; Cooke, Joseph R. and Egerod, Soren C. (1964). "ห่อหมก (ห่อ) hɔ̀ɔmòg (hɔ̀ɔ̄)," Thai-English Student's Dictionary. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. p. 577. ISBN 0-8047-0567-4

- ^ Ketthet, Boonyong. (1989). Kham thai [Thai words] คำไทย (in Thai). Bangkok: Odiant store Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-974-2-76528-6

- ^ Guoyan Zhou and Somsonge Burusphat. (1996). Languages and Cultures of The Kam-Tai (Zhuang-Dong) Group: A Word List (English-Thai version). Nakhon Pathom: Institute of Language and Culture for Rural Development Mahidol University. p. 401. ISBN 978-974-5-88596-7

- ^ Gedney, William J. (1997). William J. Gedney's Tai Dialect Studies Glossaries, Texts, and Translations. Ann Arbor, MI: Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS), The University of Michigan. p. 579. :— "mok1 'to cover, conceal'".

- ^ Li, Fang Kuei. (1977). "A Handbook of Comparative Tai," University of Hawai'i Press' Oceanic Linguistics Special Publications 1977(15): 75. :— "22. to cover, hide DIS mok --- mɔk".

- ^ McFarland, Joanna Rose. "Language Contact and Lexical Changes in Khmer and Teochew in Cambodia and Beyond," in Chia, Caroline and Hoogervorst, Tom. (2022). Sinophone Southeast Asia Sinitic Voices Across the Southern Seas. Leiden; Boston, NY: Koninklijke Bril NV. ISBN 978-900-4-47326-3 LCCN 2021-32807

- Ibid. p. 113. :— "TABLE 3.3 Breakdown of the Breakdown of the count of speakers using each word (cont.) English gloss amok, Word used '9 a11mɔk5', '2 unknown' Count, generation, gender '4G1F, G2F, 2G2M, 2G3F', 'G1M, G3F'."

- Ibid. p. 114. :— "Expansive vocabulary would be terms for local dishes like ‘papaya salad’, ‘Cambodian crepe’, ‘prahok’, ‘kralan’, ‘amok’, and ‘lok lak’ that likely did not exist in the language of the historic Teochew settlers in Cambodia. The Khmer word may have been adopted out of necessity and/or convenience. ‘Papaya salad’, ‘Cambodian crepe’, ‘prahok’, ‘amok’, and ‘lok lak’ were strongly attested in the data (by nine or more speakers), and no other words were provided as alternatives to the Khmer loanword."

- ^ Multiple sources:

- Ooi, Vincent B. Y. (2001). Evolving Identities: The English Language in Singapore and Malaysia. Singapore: Times Academic Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-981-2-10156-3 :— "Many of the words borrowed from Malay mentioned above were borrowed before the new standard spelling was available. Item amok, kampong and sarong reflect the old Malaysian spelling (and pronunciation), whereas batik was borrowed from Indonesian Malay (where the Indonesian spelling was identical to the new 'perfected spelling')".

- Winchester, Simon. (2003). The Meaning of Everything: The Story of the Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford, Oxford University Press. p. 16. ISBN 0-19-280576-2 :— "... and a gallimaufry of delights from some 50 other contributing tongues, including amok, paddy, and sago (from Malay), caravan4 and turban (Persian), ..."

- Scott, Charles Payson Gurley. "ARTICLE III: THE MALAYAN WORDS IN ENGLISH (First Part)," Journal of The American Oriental Society 17(July-December, 1896): 108. :— "The Malay word is amuk, amok (pronounce â'muk, â'mok, or â'mu, â'mo); Lampong amug, Javanese hamuk, Sundanese amuk, Dayak amok. It means ‘furious, frenzied, raging, attacking with blind frenzy’; as a noun, ‘rage, homicidal frenzy, a course of indiscriminate murder’; as a verb, mengâmuk, ‘to run amuck,’ ‘to make amok’ (Dutch amok maken, or amokken)."

- ^ Marlay, Ross and Neher, Clark D. (1999). Patriots and Tyrants: Ten Asian Leaders. Lanham, ML; Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. p. 339. ISBN 0-8476-8442-3 :— "Glossary amok: Malay word for irrational behavior."

- ^ Isaacs, Arnold R. (2022). "Chapter 7. Cambodia: "The land is broken," Without Honor: Defeat in Vietnam and Cambodia. (Updated ed.). Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. p. 182. ISBN 978-1-4766-8635-6 LCCN 2022-28158 :— "Khmer culture is one of those that traditionally permits little outward expression of hostility, and thus does not teach its people to control aggressive drives when customary restraints are loosened. It is for that reason, perhaps, that “smiling peoples” like the Khmer often turn savagely cruel when they do become violent. The phrase “running amok” was contributed to our language by the Malays, a people culturally akin to the Khmer and similarly nonaggressive: “amok” is a Malay word for someone in the grip of uncontrollable bloodlust."

- ^ Multiple sources:

- Neumann, Caryn E.; Parks, Lori L., and Parks, Joel G. (2023). Global Dishes: Favorite Meals from around the World (eBook). New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic & Professional. para. 3. ISBN 978-144-0-87648-6

- Dunston, Lara (23 May 2017). "Cambodian Fish Amok Recipe – an Authentic Steamed Fish Curry in the Old Style". Grantourismo Travels. Archived from the original on 17 June 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

'Amok' means to steam in banana leaves in Khmer

- Mouritsen, Ole G.; Styrbæk, Klavs (2021). Octopuses, Squid & Cuttlefish: Seafood for Today and for the Future. Translated by Johansen, Mariela. Springer Publishing. p. 254. ISBN 978-3-030-58026-1.

amok - (also mok, ho mok) in southeast Asian cuisine a curry that is steamed in a banana leaf, typically made with fish, galangal, and coconut cream and served with cooked rice.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- Samdech Porthinhean Chuon Nath. (1967). "ហហ្មុក," Vochneanoukram Khmer [Khmer Dictionary] វចនានុក្រមខ្មែរ (in Khmer) from Information Technology Center, Royal University of Phnom Penh. (2016, 26 December). Samdech Porthinhean Chuon Nath's Khmer Dictionary. Retrieved on 22 December 2024. "គួរកុំច្រឡំហៅ អាម៉ុក ព្រោះជាសម្តីពុំគួរសោះឡើយ". [Don't be confused with Amok because it's not a proper word.]

- Chuon, Nath (1967). វចនានុក្រមខ្មែរ [Khmer Dictionary]. Buddhist Institute.

ហហ្មុក (ហ៏-ហ្ម៉ុក) ន. (ស. ห่อหมก អ. ថ. ហ-ហ្មុក "ខ្ចប់-កប់" ឈ្មោះម្ហូបមួយប្រភេទ ធ្វើដោយត្រីស្រស់ផ្សំគ្រឿងមានកាពិបុកនិងខ្ទិះដូងជាដើម ខ្ចប់ចំហុយ: ហហ្មុកត្រីរ៉ស់, ហហ្មុកត្រីអណ្ដែងដាក់ស្លឹកញ (គួរកុំច្រឡំហៅ អាម៉ុក ព្រោះជាសម្ដីពុំគួរសោះឡើយ)។

- ^ a b Denoon, Donald; Hudson, Mark; McCormack, Gavan; and Morris-Suzuki, Tessa. (2001). "Contact with the Outside," Multicultural Japan: Paleolithic to Postmodern. New York, NY; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 156–7. ISBN 0-521-00362-8

- ^ Chotamara, Lawan. (1993). Moradok Thai [Thai food heritage] มรดกไทย (in Thai). Bangkok: Rachawadi. p. 106 ISBN 978-974-8-06001-9 :— "ห่อหมกดูจะมีบทบาทมากกว่าอื่นใดทั้งหมดเลย ขนาดต่างชาติรับเอาไปเป็นอาหารของตนเลยคือ โฮโมดุ นั่นแหละ คุณยุ่นปี่ ญี่ปุ่น พวกยามาดา พระยาเสนาภิมุขรับไปจากเมืองไทยตั้งแต่สมัยกรุงศรีอยุธยาเป็นราชธานีนั่นแน่ะ".

- ^ Supphalak, Monthian. (1998). Khanom Thai [Thai desserts] ขนมไทย (in Thai). Bangkok: S.T.P. World Media Co., Ltd. p. 70. ISBN 978-974-8-65842-1 :— "ส่วนต่างชาติก็รับเอาอาหารไทยไปทําเหมือนกัน ตัวอย่างเช่น โฮโมกุ ก็เอามาจากห่อหมกของไทยนั่นเอง คงจะเป็นพวกญี่ปุ่นที่มาอยู่บ้านเมืองไทยรุ่นยามาดาซึ่งเป็นขุนนางไทยมีบรรดาศักดิ์เป็นออกญา (เท่ากับพระยา) เสนาภิมุข ร้านอาหารบางแห่งในเมืองโอซากามีโฮโมกุขายและอวดว่าเป็นอาหารที่ได้ตํารามาจากเมืองไทยเมื่อหลายร้อยปีมาแล้ว".

- ^ The Fine Arts Department of Thailand. (1950). Sepha khun chang - khun phaen waannakhadi thai [The Khun Chang Khun Phaen poem] เสภาเรื่องขุนช้างขุนแผน (in Thai). Bangkok: Khurusapha. p. 47.

- ^ a b c Phrommathattawethi, Malithat. "อาหารการกินในวรรณกรรมเรื่องพระอภัยมณี," The Journal of the Royal Institute of Thailand 37(2)(April–June 2012): 130–31.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- Sunthon Phu and Damrong Rajanubhab. (1956). Va(a)nnakhadi Thai Pra Aphaimani. Bangkok: Khurusapha. Stanza 1063. OCLC 1389716944

- พระอภัยมณี ตอนที่ ๕๒ พระอภัยมณีทำศพท้าวสุทัศน์. Vajirayana.org. Retrieved on 23 December 2024.

- ^ a b c Phlainoi, Sombat. (1998). Kraya niyai [The food fiction: Interesting facts about Thai cuisine] กระยานิยาย: เรื่องน่ารู้สารพัดรสจากรอบๆ สํารับ (in Thai). Bangkok: Matichon. pp. 78–80, 108. ISBN 978-974-3-21014-3

- ^ Phayomyong, Manee. (2004). Prapheni sip song dan Lanna Thai [The Twelve Months Tradition of Lanna-Thai] ประเพณีสิบสองเดือนล้านนาไทย (in Thai). Chiang Mai: Center for the Promotion of Art Culture and Creative Lanna (ACCL), Chiang Mai University. pp. 86, 206. ISBN 978-974-9-26659-5

- ^ Wichitmattra (Sa-nga Kanchanakhaphan), Khun. (1999). Krung Thep mua wan ni [Bangkok in Yesterday] กรุงเทพฯ เมื่อวานนี้ (in Thai). (3rd ed.). Bangkok: Sara Khadi. p. 79. ISBN 978-974-8-21202-9

- ^ Curry: Fragrant Dishes from India, Thailand, Vietnam and Indonesia. DK. 2006. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-7566-2078-3.

- ^ Scott, Eddie. (2024). Misarana: Classic Dishes Reimagined with the Flavours of India. London: Carnival, The Quarto Group. p. 124. ISBN 978-071-1-29248-2

- ^ Ken Albala, ed. (2011). Food Cultures of the World Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. Santa Barbar, CA: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-313-37627-6

- ^ Souvanhphukdee, Andy (July 3, 2019). "Bamboo shoots steamed in Banana leaves (Mok Naw Mai)". Pha Khao Lao. Archived from the original on October 6, 2021. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ Bradley, David. (1988). Burmese Phrasebook. Melbourne: Lonely Planet. p. 70. ISBN 978-086-4-42026-8

- ^ Ritphen, Suphin and Peltier, Anatole-Roger. (1998). Khemarat Nakhon Chiang Tung เขมรัฐนครเชียงตุง [Chieng Tung, its way of life] (in Thai). Commemorative volume brought out on celebration of supreme patriarch rank given to Somdet Atchayatham of Kengtung on February 3-5, 1998. Chiang Mai: Wat Tha Kradat. p. 108. ISBN 978-974-8-62525-6

- ^ Limthanakul, Wimonsri. "บทชาติพันธุ์วรรณาว่าด้วยงานศพมอญ," Muang Boran Journal 19(3)(April-June 1993): 151. :— "พักจ๊อก (ห่อหมกไทยใหญ่)".

- ^ Alford, Jeffrey and Duguid, Naomi. (2008). "The Dai People," Beyond the Great Wall : Recipes and Travels in the Other China. New York, NY: Artisan, a division of Workman Publishing Company, Inc. p. 237. ISBN 978-1-57965-301-9

- ^ Ketthet, Bunyong. (2003). Supsan watthanatham chaatphan-Tai, saiyai chit winyan Lumnam Dam-Dæng สืบสานวัฒนธรรมชาติพันธุ์-ไท สายใยจิตวิญญาณ: ลุ่มน้ำดำ-แดง [On the culture and ethnology of the Tai ethnic minority along the Dam-Daeng River Basin in Asia] (in Thai). Bangkok: Lakphim. p. 113. ISBN 978-974-9-13229-6