Stanley Park

| Stanley Park | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of Stanley Park | |

| |

| Type | Urban park |

| Location | Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada |

| Coordinates | 49°18′N 123°08′W / 49.30°N 123.14°W |

| Area | 404.9 hectares (4.049 km2; 1,001 acres; 1.563 sq mi) |

| Created | 1888 |

| Operated by | Vancouver Park Board |

| Visitors | approx. 8 million annually[1] |

| Website | vancouver |

| Official name | Stanley Park National Historic Site of Canada |

| Designated | 1988 |

Stanley Park is a 405-hectare (1,001-acre) public park in British Columbia, Canada, that makes up the northwestern half of Vancouver's Downtown peninsula, surrounded by waters of Burrard Inlet and English Bay. The park borders the neighbourhoods of West End and Coal Harbour to its southeast, and is connected to the North Shore via the Lions Gate Bridge. The historic lighthouse on Brockton Point marks the park's easternmost point. While it is not the largest urban park, Stanley Park is about one-fifth larger than New York City's 340-hectare (840-acre) Central Park and almost half the size of London's 960-hectare (2,360-acre) Richmond Park.[2]

Stanley Park has a long history. The land was originally used by Indigenous peoples for thousands of years before British Columbia was colonized by the British during the 1858 Fraser Canyon Gold Rush and was one of the first areas to be explored in the city. For many years after colonization, the future park, with its abundant resources, would also be home to non-Indigenous settlers. The land was later turned into Vancouver's first park when the city incorporated in 1886. It was named after Lord Stanley, 16th Earl of Derby, a British politician who had recently been appointed Governor General of Canada. It was originally known as Coal Peninsula and was set aside for military fortifications to guard the entrance to Vancouver harbour. In 1886, Vancouver City Council successfully sought a lease of the park which was granted for $1 per year. In September 1888, Lord Stanley opened the park in his name.[3]: 254

Unlike other large urban parks, Stanley Park is not the creation of a landscape architect but rather the evolution of a forest and urban space over many years.[4] Most of the manmade structures present in the park were built between 1911 and 1937 under the influence of then-superintendent W.S. Rawlings. Additional attractions, such as a polar bear exhibit, aquarium, and a miniature train, were added in the post–World War II period.

Much of the park remains as densely forested as it was in the late 1800s, with about a half million trees, some of which stand as tall as 76 metres (249 ft) and are hundreds of years old.[5][6] Thousands of trees were lost (and many replanted) after three major windstorms that took place in the past 100 years, the last in 2006.

Significant effort was put into constructing the near-century-old Vancouver Seawall, which can draw thousands of people to the park in the summer.[7] The park also features forest trails, beaches, lakes, children's play areas, and the Vancouver Aquarium, among many other attractions. On June 18, 2014, Stanley Park was named "top park in the entire world" by Tripadvisor, based on reviews submitted.[8]

History

[edit]Coast Salish land

[edit]

Archaeological evidence suggests a human presence in the park dating back more than 3,000 years.[9][10] The area is the traditional territory of multiple coastal Indigenous peoples. From the Burrard Inlet and Howe Sound regions, Squamish Nation had a large village in the park. From the lower Fraser River area, Musqueam Nation used its natural resources.[11]: 20

Where Lumberman's Arch is now, there once was a large village called Whoi Whoi, or Xwayxway, roughly meaning place of masks.[12] One longhouse, built from cedar poles and slabs, was measured at 61 metres (200 ft) long by 18 metres (60 ft) wide.[11]: 46 These houses were occupied by large extended families living in different quadrants of the house. The larger houses were used for ceremonial potlatches where a host would invite guests to witness and participate in ceremonies and the giving away of property.[11]: 43

Another settlement was further west along the same shore.[13] This place was called Chaythoos, meaning high bank.[10][12] The site of Chaythoos is noted on a brass plaque placed on the lowlands east of Prospect Point commemorating the park's centennial.

Both sites were occupied in 1888, when some residents were forcefully removed to allow a road to be constructed around the park, and their midden was used for construction material.

The popular landmark Siwash Rock, located near present-day Third Beach, was once called Slahkayulsh, meaning he is standing up.[12] In the oral history, a fisherman was transformed into this rock by three powerful brothers as punishment for his immorality.[12]

In 2010, the chief of the Squamish Nation proposed renaming Stanley Park as Xwayxway Park after the large village once located in the area.[14]

European exploration

[edit]

The first European explorations of the peninsula were made by expeditions commanded by Spanish captain José María Narváez (1791) and British captain George Vancouver (1792).

In A Voyage of Discovery, Vancouver describes the area as "an island ... with a smaller island Deadman's Island (the correct name being Deadman Island) lying before it", suggesting that it was originally surrounded by water, at least at high tide.[15]: 13

Vancouver also wrote about meeting the people living there:

Here we were met by about fifty [natives] in canoes, who conducted themselves with great decorum and civility, presenting us with several fish cooked and undressed of a sort resembling smelt. These good people, finding we were inclined to make some return for their hospitality, showed much understanding in preferring iron to copper.

According to historians,[who?] the Indigenous peoples probably first saw Vancouver's ship from Chaythoos, a location in the future park that in today's terms lay just east of the Lions Gate Bridge (or First Narrows Bridge as it is sometimes called). Speaking about this event later in a conversation with archivist Major Matthews, Andy Paull, whose family lived in the area, confirms the account given by Vancouver:

As Vancouver came through the First Narrows, the [natives] in their canoes threw these feathers in great handfuls before him. They would of course rise in the air, drift along, and fall to the surface of the water, where they would rest for quite a time. It must have been a pretty scene, and duly impressed Captain Vancouver, for he speaks most highly of the reception he was accorded.[12]

No significant contact with inhabitants in the area was recorded for decades, until around the time of the Crimean War (1853–1856). British admirals arranged with Chief Joe Capilano that if there were an invasion, the British would defend the south shore of Burrard Inlet and the Squamish would defend the north.[15]: 15–16 The British gave him and his men 60 muskets. Although the attack anticipated by the British never came, the guns were used by the Squamish to repel an attack by an indigenous raid from the Euclataws. Stanley Park was not attacked, but this was when it started to be thought of as a strategic military position.[16]

Early uses of park land

[edit]

The peninsula was a popular place for gathering traditional food and materials in the 1800s, but it started to see even more activity after the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush in 1858, going through a succession of uses when non-Indigenous settlers moved into the area.

The shallow waters around the First Narrows and Coal Harbour were popular fishing spots for clams, salmon, and other fish. August Jack Khatsahlano, a celebrated dual chief of the Squamish and Musqueam who once lived at Chaythoos, remembered how he used to fish-rake in Coal Harbour and catch many herrings.[11]: 43 They would also hunt grouse, ducks, and deer on the peninsula.

Second Beach was a source of "clay ... which, when rolled into loaves, as (my people) did it, and heated or roasted before a fire, turned into a white like chalk" that was used to make wool blankets.[11]: 21

Indigenous inhabitants also cut down large cedar trees in the area for a variety of traditional purposes, such as making dugout canoes.[11]: 20

By 1860, non-Indigenous settlers (Portuguese, Scots, and others) had started building homes on the peninsula, first at Brockton Point and later on Deadman Island. "Portuguese Joe" Silvey was the first European to settle in the future park.[17] A Chinese settlement also grew in a cleared area at Anderson Point (near the present day Vancouver Rowing Club).[18]

The peninsula was surveyed and made a military reserve in an 1863 survey completed by the Royal Engineers. Despite the houses and cabins on the land, it was again considered a strategic point in case Americans attempted an invasion and launched an attack on New Westminster (then the colonial capital) via Burrard Inlet.

In 1865, Edward Stamp decided that Brockton Point would be an ideal site for a lumber mill. He cleared close to 40 hectares (100 acres) with the permission of colonial officials, but the site proved too impractical and he moved his operation east, eventually becoming Hastings Mill. The land cleared by Stamp later became the Brockton sports fields.

The future park was selectively logged by six different companies between the 1860s and 1880s, but its military status saved the land from further development.[19] Most of today's trails in Stanley Park got their start as old skid roads.[9]

Near the end of the 1800s, the city's principal reservoir was built in the area south of Prospect Point that is now a playing field and picnic area.[20] Despite the reservoir's demolition in 1948, there is still a Reservoir Trail at that location.

From the 1860s to 1880s, settlers in Burrard Inlet used Brockton Point, Anderson Point, and nearby Deadman Island as burial grounds. This practice stopped when the Mountain View Cemetery opened in 1887. Deadman Island had already had a long history as a burial site. In 1865, unsuspecting newcomer John Morton found old cedar boxes in the trees.[21] They turned out to be coffins that had been placed there to keep the remains of important Indigenous persons out of reach of wild animals.[13]

Leasing the land

[edit]

In 1886, as its first order of business, Vancouver City Council voted to petition the British government to lease the military reserve for use as a park. To manage their new acquisition, city council appointed a six-person park committee, which in 1890 was replaced with an elected body, the Vancouver Park Board.

In 1908, 20 years after the first lease, the federal government renewed the lease for 99 more years.[22]

In 2006, a letter from Parks Canada stated that "the Stanley Park lease is perpetually renewable and no action is required by the Park Board in relation to the renewal".

Opening and dedication

[edit]

On September 27, 1888, the park was officially opened (although the legal status of Deadman Island as part of the park would remain ambiguous for many years). The park was named after Lord Stanley, who had recently become Canada's sixth governor general.[1] Mayor David Oppenheimer gave a formal speech opening the park to the public and delivering authority for its management to the park committee.[23]: 3 [24][25]: 63–75

The following year, Lord Stanley became the first governor general to visit Vancouver when he officially dedicated the park. Mayor Oppenheimer led a procession of vehicles around Brockton Point along the newly completed Park Road to the clearing at Prospect Point. An observer at the event wrote:

Lord Stanley threw his arms to the heavens, as though embracing within them the whole of 1000 acres of primeval forest, and dedicated it "to the use and enjoyment of peoples of all colours, creeds, and customs, for all time. I name thee Stanley Park."[26]

Eviction of pre-park residents

[edit]

When Lord Stanley made his declaration, there were still a number of homes on lands he had claimed for the park. Some, who had built their homes less than twenty years earlier, would continue to live on the land for years. Most were evicted by the park board in 1931, but the last resident, Tim Cummings, lived at Brockton Point until his death in 1958.[27]

Sarah Avison, the daughter of the first park ranger, recalled when the city evicted the Chinese settlers at Anderson Point in 1889:

The Park Board ordered the [Chinese settlers] to leave the park; they were trespassers; but [they] would not go, so the Park Board told my father to set fire to the buildings. I saw them burn; there were five of us children, and you know what children are like when there is a fire. So father set fire to the shacks; what happened to the Chinese I do not know.[28]

Most of the dwellings at Xwayxway were reported vacant by 1899, and in 1900, two of such houses were purchased by the park board for $25 each and burned. One Squamish family, "Howe Sound Jack" and Sexwalia "Aunt Sally" Kulkalem, continued to live at Xwayxway until Sally died in 1923. Sally's ownership of the property surrounding her home was accepted by authorities in the 1920s, and following her death, the property was purchased from her heir, Mariah Kulkalem, for $15,500 and resold to the federal government.[20]

Although most residents of the area were evicted by the early 20th century, the municipal government still owns a number of field homes used by the park's "live-in caretakers".[29] Caretakers that occupy the field homes are not charged rent by the city, although they are required to assist in park operations and provide a permanent presence for the park board.[29] In 2006, the City of Vancouver decided it would no longer replace live-in caretakers who retired or moved out from the field homes, with the city opting to convert several unoccupied field homes into artist studios.[29]

Construction of Lost Lagoon and causeway

[edit]From 1913 to 1916, a lake was constructed in a shallow part of Coal Harbour, a project that was not without its detractors. The lake was named Lost Lagoon due to its history of "disappearing" at low tide. The lake and a causeway into the park were designed by Thomas Mawson, who also designed a lighthouse for Brockton Point around the same time. Before the causeway, a wooden footbridge provided the only access route into the park from Coal Harbour. Construction of the causeway (and new roads within the park for emergency access) was completed by 1926.[27]

In 1923, the saltwater pipes entering the lake from Coal Harbour were shut off, turning it into a freshwater lake. A lit fountain was later erected to commemorate the city's golden jubilee. The fountain, installed in 1936, was purchased from Chicago, a leftover from its world's fair in 1933.[30]

The causeway was widened and extended through the centre of the park in the 1930s with the construction of the Lions Gate Bridge, which connects downtown Vancouver to the North Shore. At the same time, two pedestrian subways were added under the causeway at the entrance to the park from Georgia Street.

By the 1950s, visitors could take rented rowboats on Lost Lagoon, but boating and other activities were banned in 1973 as the lake became a bird sanctuary. By 1995, the old boathouse had been turned into the Lost Lagoon Nature House. It is operated by the Stanley Park Ecology Society, which is a nonprofit organization that works alongside of the Vancouver Park Board to promote stewardship and conservation in Stanley Park.[31][32][33]

Seawall

[edit]

Construction of the 8.8-kilometre (5.5 mi) seawall and walkway around the park began in 1917 and took several decades to complete.[34] The original idea for the seawall is attributed to park board superintendent W. S. Rawlings, who conveyed his vision in 1918:

It is not difficult to imagine what the realization of such an undertaking would mean to the attractions of the park and personally I doubt if there exists anywhere on this continent such possibilities of a combined park and marine walk as we have in Stanley Park.[35]

James "Jimmy" Cunningham, a master mason, dedicated 32 years of his life to the construction of the seawall from 1931 until his retirement in 1963. Cunningham continued to return to monitor the wall's progress until his death at 85.[35]

The walkway was extended several times and, as of 2023, is 22 kilometres (14 mi) from end to end, making it the world's longest uninterrupted waterfront walkway.[36] The Stanley Park portion is just under half of the entire length, which starts at Canada Place in the downtown core, runs around Stanley Park, along English Bay, around False Creek, and finally to Kitsilano Beach. From there, a trail continues 600 metres (2,000 ft) to the west, connecting to an additional 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) of beaches and pathways that terminate at the mouth of the Fraser River.

Swimming pools

[edit]

By 1933, there were two seaside, saltwater pools in the park, one at Second Beach and one at Lumberman's Arch. These "draw and fill" pools used sun-warmed water from the ocean. Once a week, the pool gates were opened at low tide to release the water back into the ocean, before the next high tide of clean water.

For many years, children could take swimming lessons for free at Lumberman's Arch under the Vancouver Sun's Learn to Swim program. The pool was filled in after developing persistent problems and replaced with the current water spray park in 1987. The spray park, the largest of its kind in Vancouver, consists of a series of water geysers, showers, and cannons.[citation needed]

In 1995, after more than 60 years of operation, the Second Beach pool was shut down because it failed to meet new health standards. By 1996, it had been replaced with the current heated pool.[citation needed]

At both locations, remnants of the old pool's semicircle shaped outer wall can still be seen.

In wartime

[edit]

In World War I, a gun battery (without a bunker) was placed at Siwash Point (above Siwash Rock) to protect the city from possible attacks from German merchant raiders.[25]: 164 It was removed just prior to the end of the war in 1918.[25]: 165

In 1936, when the Empire of Japan began large-scale military repression in northeast China, the perceived Japanese threat resulted in fortifications being erected in Stanley Park, among other areas.[38] In Stanley Park, a watch tower was built on the cliff directly above Siwash Rock and remains intact as an observation deck that is accessed from the trails above.

By 1940, a gun battery and bunker had been built at Ferguson Point, just east of Third Beach. The military also expanded its use of the park by closing the area around Ferguson Point and Third Beach, where it had established barracks for the battery detachment and was providing training.[39][25] What is now the Teahouse Restaurant was originally built as an officers' mess.[30] The bunker was buried and battery removed around the end of the war.

The army built several other coastal defence forts for the Second World War, as shown in the illustration at right, most notably at Tower Beach in Point Grey. In addition, an examination area was set up where any ships requesting entrance to the harbour had to stop and submit to an inspection.[37]

Zoo and Children's Farmyard

[edit]

From the very beginning, the park kept and exhibited animals after the first park ranger, Henry Avison, captured an orphaned black bear cub and chained it to a stump for safety in 1888. By 1905, several animals had been donated: a monkey, a large seal, four grass parakeets, a raccoon, a canary, and a black bear. Avison was subsequently named city pound keeper, and his collection of animals formed the basis for the original zoo, which eventually housed over 50 animals, including snakes, wolves, emus, bison, kangaroos, monkeys, and Humboldt penguins.[23]: 13

By the 1970s, the zoo – with its new polar bear exhibit, built in 1962 – had become the park's main attraction. Today the only remnant of the old zoo is a large concrete grotto where the polar bears had entertained crowds for many years until the 1990s. In 1994, when plans were developed to upgrade the zoo, Vancouver voters instead decided to phase it out when the question was posed in a referendum. The zoo was shut down in 1996 and the animals were either moved to the petting zoo area, the Greater Vancouver Zoo in Aldergrove, or to other facilities.

The Stanley Park Zoo closed completely in December 1997 after the last remaining animal, a polar bear named Tuk, died at age 36. He had remained after the other animals had left because of his old age. The polar bear grotto, often criticized by animal rights activists, was to be converted into a demonstration salmon spawning hatchery.[40]

The Stanley Park Children's Farmyard (petting zoo) opened in 1982. It was a successor to the original children's zoo that started in 1950. Domestic animals and a few reptiles and birds were kept in the Children's Farmyard until it closed in 2011.[41][42]

Aquarium

[edit]The aquarium opened in 1956 after complicated negotiations, followed by a massive expansion in 1967. It was the first facility in the world to study a killer whale (1964), its researchers discovered a new species of shrimp in the Gulf Islands (1997), and it became the first aquarium to ensure that it would never result in the capture of a wild whale or dolphin (1996).[30] The popular children's song "Baby Beluga" was inspired by one of the whales at the facility.

In 2006, the park board approved an $80-million expansion of the facility following considerable public debate, including vocal opposition regarding animal rights and the loss of park trees required by the expansion.[43]

1960s counterculture

[edit]By the 1960s, the neighbourhood around Stanley Park was similar to present day Commercial Drive, attracting many of the city's beatniks and flower children. This made Stanley Park the perfect place for be-ins, a type of counterculture event inspired by the Human Be-In started in San Francisco. The Stanley Park event started on Easter weekend in 1967 and took place each spring until the mid-1970s, when most of the counterculture movement had fizzled out. At its peak, thousands would assemble at Ceperley Meadows near Second Beach to listen to bands, speakers, and poets, and socialize.[44][45]

Storms and loss of landmark trees

[edit]

Violent windstorms have struck Stanley Park and felled many of its trees numerous times in the past. Between 1900 and 1960, nineteen separate windstorms swept through the park, causing significant damage to the forest cover. The park lost some of its oldest trees through major storms twice in the last century and then again in 2006. The first was a combination of an October windstorm in 1934 and a subsequent snowstorm the following January that felled thousands of trees, primarily between Beaver Lake and Prospect Point.[46][47]

Another storm in October 1962, the remnants of Typhoon Freda, cleared a 2.4-hectare (6-acre) virgin tract behind the children's zoo, which opened an area for a new miniature railway that replaced a smaller version built in the 1940s. In total, approximately 3,000 trees were lost in that storm.[48]

One stand of tall trees in the centre of the park did not survive beyond the 1960s after becoming a popular tourist attraction. The “Seven Sisters” are memorialized by a plaque and young replacement trees in the same location along Lovers Walk, a forest trail that connects Beaver Lake with Second Beach. "They were so popular that people basically killed them by walking on their roots", said historian John Atkin.[27]

The death of the distinctive fir tree atop Siwash Rock has also been memorialized with a replacement. The original died in the dry summer of 1965, and through the persistent efforts of park staff, a replacement finally took root in 1968.[49][50]

Another major windstorm ravaged the park on December 15, 2006, with 115 kilometres per hour (71 mph) winds (Hanukkah Eve windstorm). Over 60 percent of the western edge was damaged; the worst part was the area around Prospect Point.[51] In total, about 40 percent of the forest was affected, with an estimated 10,000 trees downed.[52] Large sections of the seawall were also destabilized by the storm, and many areas of the park were closed to the public pending restoration. The cost of restoration was estimated at $9 million, which was covered by contributions from all three levels of government and private and corporate donations.[53]

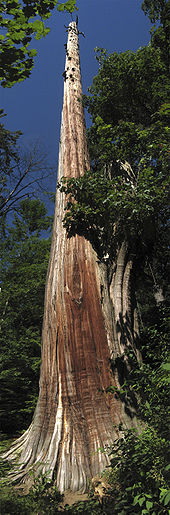

Two landmark trees were affected. One tree that has achieved a lot of fame is the National Geographic Tree, so named because it appeared in the magazine's October 1978 issue. With a circumference of 13.5 m (44.3 ft), it was once one of the more impressive big western red cedars of the park. It diminished over time, ravaged by storms, a lightning strike, and topped by park staff to a height of 39.6 metres (130 ft) before being uprooted in October 2007.[54][55][56]

The Hollow Tree was probably the most photographed park element in bygone years, an obligatory stop for locals, tourists and dignitaries alike; a professional photographer was on hand to capture the visit for a fee. The tree was saved from road widening in 1910 through the lobbying efforts of the photographer who made his living at the tree.[57] Automobiles and horse-drawn carriages would frequently be backed into the hollow, demonstrating the immensity of the tree for posterity. While the remaining 700- to 800-year-old stump still draws viewers and is commemorated with a plaque, it is no longer alive and has shrunk considerably over the years, from a circumference of 18.3 metres (60 ft) many decades ago, to a more recent 17.1 metres (56 ft).[54][55] Damaged by the December 2006 windstorm and leaning forward at a dangerous angle, on March 31, 2008, the tree was selected by the Vancouver Park Board for removal due to potential safety hazards.[58] However, on January 19, 2009, the board accepted a proposal to save the tree by realigning and stabilizing it at a cost of $250,000, funded entirely by private donations.[59]

National Historic Site designation

[edit]The park was designated a National Historic Site of Canada by the federal government in 1988. It was deemed significant because the relationship between its "natural environmental and its cultural elements developed over time" and because "it epitomizes the large urban park in Canada".[60]

21st century

[edit]The forest continues to give the park a more natural character than most other urban parks, leading many to call it an urban oasis.[61] It consists primarily of second and third growth and contains many tall Douglas fir, western red cedar, western hemlock, and Sitka spruce trees. Since 1992, the tallest trees have been topped and pruned by park staff for safety reasons.

A large variety of animals live in the park. There are 200 bird species alone, including many water birds. A large great blue heron colony moved into the park in 2001 and has grown to now about 170 active nests.[62] Mammals include a large raccoon population, coyotes, skunks, beavers, rabbits descended from discarded pets, and a thriving grey squirrel population (descended from eight pairs acquired from New York's Central Park in 1909).[54][61] However, there is a complete absence of large mammals, including deer, elk, bear, wolves, cougars, and bobcats.[63]

There have been occasional attacks by coyotes on humans in the park, but in the nine months from December 2020, during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, there was a major increase in frequency: forty attacks by the estimated twelve coyotes in the park, none fatal, took place, four times more than all the attacks in the previous thirty years. No explanation had been found as of August 2021[update], not even whether the attacks were by one coyote or different animals. Several coyotes were killed, but the frequency of attacks did not decrease.[64]

Stanley Park also has many manmade attractions. Recreational facilities are especially abundant in the park, having long coexisted, albeit uneasily, with the aesthetic and more natural park features preferred by those looking to the park as an enclave of nature in the city.[65]

Recognition

[edit]Stanley Park was named the best park in the world in 2013, according to website Tripadvisor's first ever Travellers' Choice Awards. Central Park in New York took second place and Colorado's Garden of the Gods took third place.[66]

Attractions

[edit]

The Vancouver Seawall is popular for walking, running, cycling, inline skating, and even fishing (with a licence). There are two paths, one for skaters and cyclists and the other for pedestrians. The lane for cyclists and skaters goes one-way in a counterclockwise loop.[35] Walking the entire loop around Stanley Park takes about two hours, while biking it takes about one hour.

There are also more than 27 kilometres (17 mi) of forest trails inside the park.[67] Forest trails are patrolled by members of the Vancouver Police Department on horseback.[68] The police department mounted unit's youth outreach includes offering guided tours of the stables and the "Collector's Trading Card Program", which encourages children of all ages to approach a constable on horseback and request a card.

The 20 in (508 mm) narrow-gauge[69] Stanley Park Railway, a ridable miniature railway with different seasonal themes, is a Vancouver tradition, especially for families with young children. The original railway, started in 1947, featured a child-sized train. The current adult-sized railroad opened in 1964 in an area leveled by Typhoon Freda. The engine is a replica of Canadian Pacific 374, the first transcontinental passenger train to arrive in Vancouver in the 1880s.[70]

The 2006 windstorm revealed traces of a long-forgotten rock garden, which had once been one of the park's star attractions and one of its largest man-made objects by area.[71][72] Soon after its discovery, a section that encircles part of the Stanley Park Pavilion was restored (the garden had originally extended from Pipeline Road to Coal Harbour).[73]

Beaver Lake is a restful space nestled among the trees. The lake is almost completely covered with water lilies (introduced for the Queen's Jubilee in 1938) and home to beavers, fish, and water birds. As of 1997, its surface area was just short of 4 hectares (10 acres), but the lake is slowly shrinking in size.[74] One of Vancouver's few remaining free-flowing streams, Beaver Creek, joins Beaver Lake to the Pacific Ocean and is one of two streams in Vancouver where salmon still return to spawn each year.[74][75]

Lost Lagoon, the captive 17-hectare (41-acre) freshwater lake near the Georgia Street entrance to the park, is a nesting ground to many bird species, such as Canada geese and ducks.

The Vancouver Aquarium is the largest in Canada and houses a collection of marine life that includes sea lions, harbour seals, and sea otters. In total, there are approximately 300 species of fish, 30,000 invertebrates, 56 species of amphibians and reptiles, and around 60 mammals and birds.[76] The aquarium is also home to a 4D theatre.

The oldest manmade landmark in the park is an 1816 naval cannon located near Brockton Point. The 9 O'Clock Gun, as it is known today, was fired for the first time in 1898, a tradition that has continued for more than 100 years.[30] The cannon was originally detonated with a stick of dynamite but is now activated automatically with an electronic trigger.

Stanley Park also has playgrounds, sandy beaches, gardens, tennis courts, an 18-hole pitch and putt golf course, a seaside swimming pool, a water spray park, and Brockton Oval, which is used for track sports, rugby, and cricket.

In summer, there is an outdoor theatre Malkin Bowl, which features events by Theatre Under The Stars and Live Nation (with their Concerts in the Park series).[2]

Monuments

[edit]

The park has a large number of monuments, including statues, plaques, and gardens. Among these are the Japanese Canadian War Memorial (a cenotaph and two rows of Japanese cherry Prunus Shirotae trees) and statues of poet Robert Burns, Olympic runner Harry Jerome, and Girl in a Wetsuit.

The park board has banned the erection of any further memorials to ensure that Stanley Park is kept in a more natural state (and based on the view that it is already saturated). As an exception to the ban, the park board agreed in 2006 to build a new playground at Ceperley Meadows near Second Beach honouring the victims of the Air India Flight 182 bombing. The federal government spent approximately $800,000 to build the memorial and playground.[78]

Great blue herons

[edit]Stanley Park is home to one of the largest urban great blue heron colonies in North America, and the birds have been documented nesting in various locations in Stanley Park as far back as 1921. Great blue herons are classified as a species at risk in British Columbia, and the Stanley Park Ecology Society has been monitoring the heronry in Stanley Park since 2004.[62] An estimated 156 young Pacific great blue herons fledged from the colony in 2013.[79] Since monitoring started in 2007, the highest number of great blue herons fledged in a year were 258, in 2007. The lowest number of fledges was in 2011 with just 99 of the birds fledged.[80]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Vancouver Park Board Parks and Gardens: Stanley Park". Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- ^ a b Foss, Lindsay. "A Walk through Stanley Park". Travel. Canadian Geographic. Archived from the original on June 20, 2007. Retrieved 2006-12-10.

- ^ Akrigg, G.P.V.; Akrigg, Helen B. (1986), British Columbia Place Names (3rd, 1997 ed.), Vancouver: UBC Press, ISBN 0-7748-0636-2

- ^ Stephan, Bill; Vancouver Natural History Society (2006). Wilderness on the Doorstep: Discovering Nature in Stanley Park. Vancouver: Harbour Publishing. p. 17. ISBN 1-55017-386-3.

- ^ Parkinson, Alison; Taylor, Terry; Vancouver Natural History Society (2006). Wilderness on the Doorstep: Discovering Nature in Stanley Park. Vancouver: Harbour Publishing. pp. 54, 52. ISBN 1-55017-386-3.

- ^ "Welcome to Stanley Park". Parks and Gardens. Vancouver Park Board. Archived from the original on 2006-09-27. Retrieved 2006-12-20.

- ^ "Stanley Park Cycling Plan". City of Vancouver. Retrieved 2013-08-15.

- ^ Judd, Amy (June 18, 2014). "World Park Rankings". Global News. Retrieved 2014-06-18.

- ^ a b Kheraj, Sean. "Historical Overview of Stanley Park" (PDF). Stanley Park Ecology Society. Retrieved 2013-08-15.

- ^ a b Shore, Randy (March 17, 2007). "Before Stanley Park: First nations sites lie scattered throughout the area". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 2013-08-15.

- ^ a b c d e f Barman, Jean (2007) [2005]. Stanley Park's Secret: The Forgotten Families of Whoi Whoi, Kanaka Ranch and Brockton Point. Madeira Park, BC: Harbour Publishing. ISBN 978-1-55017-420-5.

- ^ a b c d e Matthews, Major James Skitt (2011) [1933]. "Early Vancouver Volume 2: Narrative of Pioneers of Vancouver, BC Collected During 1932". City of Vancouver. Retrieved 2013-08-16.

- ^ a b Matthews, Major James Skitt. "Conversations with Khahtsahlano 1932-1954". City of Vancouver. Retrieved 2013-08-16.

- ^ "Natives urge Stanley Park name change". CBC News. 2010-07-01.

- ^ a b Nicol, Eric (1970). Vancouver. Toronto: Doubleday.

- ^ Paull, Andy (26 March 1938). "The Battle-Ground of Stanley Park". Vancouver Sun.

- ^ "Stanley Park Timeline created by John Atkin". Vancouver Park Board. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- ^ Sherlock, Tracy (17 August 2013). "Looking back at our favourite park". Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ "Forest – Monument Trees". Stanley Park Nature. City of Vancouver. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved 2006-12-20.

- ^ a b Historical and Geographical Contexts Archived 2021-01-05 at the Wayback Machine, Stanley Park Commemorative Integrity Statement, Parks Canada.

- ^ Steele, Richard M. (1993). The Stanley Park explorer (Stanley Park ed.). Heritage House Publishing Co. ISBN 1-895811-00-7. OL 24831611M. 1895811007.

- ^ "The History of Metropolitan Vancouver: 1908". Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- ^ a b Steele, R. Mike (1988). The Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation: The First 100 Years. Vancouver: Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation.

- ^ Kheraj, Sean (2008). "Improving Nature: Remaking Stanley Park's Forest, 1888-1931" (PDF). BC Studies. 158: 63–90. Retrieved 2017-01-11.

- ^ a b c d Kheraj, Sean (2013). Inventing Stanley Park: An Environmental History. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-2426-2. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ^ Davis, Chuck; Conn, Heather (1997). The Greater Vancouver Book: An Urban Encyclopedia. Surrey, BC: Linkman Press. p. 52. ISBN 1-896846-00-9. Archived from the original on 2009-06-20.

- ^ a b c Mackie, John (August 17, 2013). "Stanley Park, the natural wonder of Vancouver, was shaped by humans". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- ^ Kheraj, Sean. "Creature Comforts: Remaking the Animal Landscape of Vancouver's Stanley Park, 1887-1911" (PDF). University of Toronto. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ a b c Redekop, Arlen (3 November 2014). "Last of the live-in caretakers: Vancouver park workers will be last to stay rent-free in idyllic fieldhouses". National Post. Postmedia Network. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d Davis, Chuck (April 4, 2010). "124 Years of Vancouver Oddities". Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ^ Vancouver, City of. "Stories from inside Stanley Park: historical glimpses of park attractions and businesses". vancouver.ca. Retrieved 2022-10-02.

- ^ "Stanley Park Ecology Society (SPES)". Archived 2014-04-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Stanley Park Ecology Society (SPES)". Stanley Park Ecology Society (SPES). Retrieved 2022-10-02.

- ^ "Last stone laid in park's seawall". Vancouver Sun. 27 September 1971.

- ^ a b c Griffin, Kevin; Clark, Terri (4 February 2005). "Grand Old Man of the Seawall". Vancouver Sun.

- ^ Pleiff, Margo (2005-05-15). "Vancouver seawall links city's urban and natural delights". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2006-12-01.

- ^ a b Platt, Brian (December 5, 2011). "Pearl Harbor 70th Anniversary: Fortress UBC". The Ubyssey. Archived from the original on 2013-09-27. Retrieved 2013-08-22.

- ^ Muir, Stewart (March 15, 2012). "Part Six: Military leaders insisted Japan was no threat to West Coast". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved March 15, 2012.

- ^ "CWACs & the Paparazzis". November 27, 2011. Archived from the original on 2013-08-15. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ^ "Vancouver residents say no to Stanley Park Zoo". Edmonton Journal. 28 April 1996.

- ^ "Vancouver petting zoo, conservatory face cuts". CBC News. 18 November 2009. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ Fralic, Shelley (7 January 2011). "Closure of Stanley Park's petting zoo is PC madness". Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ "Board of Parks and Recreation Special Board Meeting". Vancouver Park Board. 2006-11-27. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2006-12-28.

- ^ "Be-In Music Festival – Vancouver Canada". Voices of East Anglia. Archived from the original on 2013-07-13. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ Smith, Charlie (August 21, 2013). "Vision Vancouver boosts live music in local parks". The Georgia Straight. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ "The Damage in the Park". Vancouver Daily Province. 9 February 1934.

- ^ Kheraj, Sean (2007). "Restoring Nature: Ecology, Memory, and the Storm History of Vancouver's Stanley Park". Canadian Historical Review. 88 (4): 577–612. doi:10.3138/chr.88.4.577.

- ^ Hazlitt, Tom (22 May 1964). "It's for real – this railroad". Vancouver Daily Province.

- ^ "Park Tree's Loss Stirs Memories". Vancouver Sun. 10 August 1965.

- ^ "Park Still Feels Frieda's Punch". Vancouver Sun. 6 August 1968.

- ^ Rook, Katie (2006-12-19). "Stanley Park 'looks like a war zone'". National Post. Archived from the original on 2007-03-13. Retrieved 2006-12-20.

- ^ Ellison, Marc (6 December 2011). "Stanley Park five years after the storm". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ "Stanley Park restoration cost rises to $9 million". Vancouver Sun. 2007-01-27. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2007-02-08.

- ^ a b c Steele, Mike (1993). Vancouver's Famous Stanley Park: The Year-Round Playground. Vancouver: Heritage House. p. 108. ISBN 1-895811-00-7.

- ^ a b Parkinson, Alison (2006). Wilderness on the Doorstep: Discovering Nature in Stanley Park. Vancouver: Harbour Publishing. p. 46. ISBN 1-55017-386-3.

- ^ "Ancient cedar falls in Vancouver's Stanley Park". CBC News. 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ^ Koshevoy, Himie (7 June 1962). "Saga of Stanley Park". Vancouver Daily Province.

- ^ "Stanley Park's hollow tree gets the axe". CBC News. April 1, 2008.

- ^ "Stanley Park's Hollow Tree spared the axe for good". CBC News. January 19, 2009.

- ^ Parks Canada; Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation (2002-11-26). "Stanley Park: Commemorative Integrity Statement" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-04. Retrieved 2006-12-28.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b "Stanley Park – Vancouver's Urban Oasis" (PDF). Tourism Vancouver. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-12-30. Retrieved 2006-12-20.

- ^ a b "Vancouver's Great Blue Herons". Stanley Park Ecology Society. Archived from the original on 10 July 2014. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ State of the Park Report for the Ecological Integrity of Stanley Park (PDF) (Report). Stanley Park Ecology Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2013-08-25.

- ^ Cecco, Leyland (24 August 2021). "Mystery over surge in coyote attacks in Vancouver park". The Guardian.

- ^ McDonald, Robert A. J. (1984). ""Holy Retreat" or "Practical Breathing Spot"? Class Perceptions of Vancouver's Stanley Park, 1910–1913". Canadian Historical Review. LXV (2): 139–140. doi:10.3138/chr-065-02-01. S2CID 161126439.

- ^ Ip, Stephanie (29 June 2013). "Vancouver's Stanley Park named world's best park". The Province. Archived from the original on 2013-09-16. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ "Stanley Park Trails". City of Vancouver. Retrieved 2013-08-14.

- ^ "The Mounted Squad Today". Mounted Squad, Patrol District One. Vancouver Police Department. Archived from the original on February 21, 2005. Retrieved 2006-12-16.

- ^ [KidsVancouver.com - Stanley Park Train - Miniature Railway][full citation needed]

- ^ "Stanley Park Miniature Train". City of Vancouver. Retrieved 2013-08-26.

- ^ Hasiuk, Mark (2007-02-06). "Wind exposed more of historic rockery". Vancouver Courier. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ^ O'Connor, Naoibh (2006-08-18). "Lost garden of Stanley Park". Vancouver Courier. Archived from the original on October 18, 2006. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ^ "Historic Stanley Park Rock Garden Returns". Global News. 2013-08-16. Archived from the original on 2013-11-12. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- ^ a b "Beaver Lake Environmental Enhancement Project" (PDF). Vancouver Park Board. 1997-05-30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-01. Retrieved 2008-07-22.

- ^ Hume, Mark (December 2000). "The Lost Streams". Archived from the original on 2008-05-13. Retrieved 2008-07-22.

- ^ "Meet Our Amazing Animals". Vancouver Aquarium. Retrieved 2023-08-20.

- ^ "Japanese War Memorial Stanley Park". National Inventory of Canadian Military Memorials. National Defence Canada. 2008-04-16. Archived from the original on 2014-05-29. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ Kittleberg, Lori (2006-07-06). "Air India tribute proposed for Ceperley Park". Xtra West!. Retrieved 2006-12-10.

- ^ "Pacific great blue herons return to Stanley Park after successful 2013 season". City of Vancouver. 10 March 2014. Archived from the original on 5 November 2014. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ Straker, Dan (December 2013). Stanley Park Great Blue Heronry Annual Report 2013 (PDF) (Report). Stanley Park Ecology Society. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2014. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Grant, Paul; Dickson, Laurie (2003). The Stanley Park Companion. Winlaw, B.C.: Bluefield. ISBN 1894404165.

- Steele, Richard M. (1993). Stanley Park. Surrey, B.C.: Heritage House. ISBN 1895811007.

Fiction

[edit]- Taylor, Timothy (2001). Stanley Park. Toronto, ON: Vintage Canada. ISBN 0676973094.

- Lowry, Malcolm (2009). The Bravest Boat. Don Mills, ON: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195430066.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

External links

[edit]Official websites

[edit]- Welcome to Stanley Park – City of Vancouver website

- Story of Stanley Park – City of Vancouver website

- Future of Stanley Park – City of Vancouver website

- Park Ecology - Stanley Park Ecology Society website

- Stanley Park (silent highlight reel made over the 1930s-50s) - City of Vancouver Archives website

- Our Outdoor Heritage (silent highlight reel made in 1940) - City of Vancouver Archives website

- Stanley Park Collection - A collection of sixty glass plate negatives from the UBC Library Digital Collections documenting Vancouver's Stanley Park in 1912

Additional information

[edit] Stanley Park and the West End travel guide from Wikivoyage

Stanley Park and the West End travel guide from Wikivoyage- Stanley Park Invasive Plants - Clearing of invasive plants by independent volunteers

- Interactive Map - Heart of the Park: Stanley Park celebrates 125 years - CBC website

- Archive Photos of Stanley Park - Miss 604 website

- On the Spot (short film about the Stanley Park Zoo in 1953) - National Film Board website

- Stanley Park, the natural wonder of Vancouver, was shaped by humans (2013) - Vancouver Sun article

- In the Shadows: the Darker Side of Stanley Park (2013) - Globe and Mail article

- The Secrets of Stanley Park (2013) - Vancouver Sun article

- History has forgotten existence of a thriving First Nations community in Stanley Park (2013) - The Province article

- Stanley Park page, Vancouver Then and Now website, comparisons of today's park with older photos

- 1888 establishments in British Columbia

- Former zoos

- National Historic Sites in British Columbia

- Nature centres in British Columbia

- Parks in Vancouver

- Rugby league stadiums in Canada

- Stanley Park

- Tourist attractions in Vancouver

- Zoos disestablished in the 20th century

- Educational organizations disestablished in 1997

- Zoos disestablished in the 21st century

- Educational organizations disestablished in 2011