Southampton Power Station

| Southampton power station | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Location | Southampton |

| Coordinates | 50°54′23″N 1°24′34″W / 50.9063°N 1.4095°W |

| Status | Decommissioned and demolished |

| Construction began | 1902 |

| Decommission date | c. 1977 |

| Owners | Southampton Electric Lighting and Power Company (1891–1896) Southampton Corporation (1896–1948) British Electricity Authority (1948–1955) Central Electricity Authority (1955–1957) Central Electricity Generating Board (1958–1977) |

| Operator | As owner |

| Thermal power station | |

| Primary fuel | Coal |

| Turbine technology | Steam turbines and reciprocating engines |

| Cooling towers | None |

| Cooling source | Seawater |

| Power generation | |

| Units decommissioned | All |

| Nameplate capacity | 13.26 MW (1923), 88 MW (1956) |

| Annual net output | 10.95 GWh (1923), 149 GWh (1954), 63 GWh (1963) |

Southampton Power Station was a coal fired power station built by Southampton Corporation that operated between 1904 and 1977.[1]

History

[edit]The Southampton Electric Lighting and Power Company supplied electricity to Southampton from 1891, from a small power station at Back-of-the-Walls. Southampton Corporation purchased the Company in 1896 for £21,000.[2]

By 1897, the plant had a generating capacity of 300 kW with a maximum load of 262 kW. A total of 191.868 MWh of electricity was sold which provided an income to the corporation of £4,276-4-6.[3]

The Corporation built a larger power station in 1903-4 on reclaimed land near the western end of Southampton Railway Tunnel.[1] In the same year, a siding was built from the railway to the site of the power plant.[1] The siding was initially used to bring construction materials onto the site but once construction was complete the siding was used to move coal.[1] The siding was worked by an 0-4-0 locomotive built by Southampton Corporation Tramways workshops powered by electric overhead wires.[1]

In 1925 American hard-shelled clams were introduced into the River Test, in an area warmed by cooling water discharge of the power station. This was done as an attempt to breed them to allow them to be used as eel bait.[4] Since their introduction the clams have spread through Southampton water and into Portsmouth Harbour and Langstone Harbour.[4]

The power station expanded in the 1920s.[1] This expansion required an extra train which was purchased in 1931 from Baguley (Engineers) Ltd.[1] Further increase in demand resulted in a third locomotive being purchased in 1939 this time from Greenwood & Batley.[1]

Specification

[edit]By 1923 the plant at Southampton power station comprised 1 × 1,500 kW, 1 × 3,000 kW and 1 × 5,000 kW turbo-alternators producing alternating current.[5] There was also 1 × 1,260 kW turbo-alternator and 1 × 500 kW and 2 × 1,000 kW reciprocating engines producing direct current. All these machines were fed with steam at up to 274,000 pounds per hour. The maximum load on the system was 6,824 kW and in 1923 there were 15,747 consumers connected.[5] Electricity was available to consumers at 415 & 240, 3-phase, 50 Hz AC; 200 V, 2-phase, 50 Hz AC; 400 & 200 V DC; and 500 V DC for traction current. In 1923 a total of 10.947 GWh of electricity was sold. This generated revenue of £128,192, and the surplus of revenue over expenses of £48,336 for the corporation.[5]

By the 1950s the plant at Southampton power station comprised:[6]

- Steam plant: nine Babcock and Wilcox coal-fired boilers:

Cooling was by seawater.[6]

- Generating plant

- One 7 MW Metropolitan-Vickers LP turbo-alternator

- One 6 MW Parsons LP turbo-alternator

- One 10 MW Fraser & Chalmers - GEC LP turbo-alternator

- One 15 MW Fraser & Chalmers - GEC LP turbo-alternator

- Two 25 MW Parsons HP turbo-alternators

Nationalisation

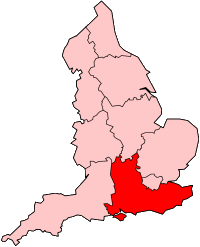

[edit]Upon nationalisation of the British electricity supply industry in 1948 the ownership of Southampton power station was vested in the British Electricity Authority, and subsequently the Central Electricity Authority and the Central Electricity Generating Board (CEGB). The electricity distribution and sales functions were vested in the South Western Electricity Board.[7]

After World War 2 the supply of coal switched to road transport and the siding ceased to be used.[1] The Southampton Corporation Tramways built locomotive was scrapped in 1953 with the remaining two meeting the same fate in 1960.[1] The siding was removed in 1964.[1]

Operations

[edit]The electricity output from the station was as follows.[6][8][9][10]

| Year | Electricity sent out, GWh |

|---|---|

| 1946 | 154.35 |

| 1954 | 148.61 |

| 1955 | 106.25 |

| 1956 | 150.95 |

| 1957 | 130.80 |

| 1958 | 89.94 |

| 1961 | 50.85 |

| 1962 | 32.99 |

| 1963 | 63.09 |

| 1967 | 44.31 |

In 1951 extractors were added to the plant to reduce the level of grit in the smoke.[11]

The power station closed in 1977 and was demolished the same year.[1] Southampton power station does not appear in the CEGB list of operational power stations in 1972.[12]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Drummond, Ian (2013). Southern Rails On Southampton Docks Including the Industrial Lines of Southampton. Holne Publishing. pp. 155–158. ISBN 9780956331748.

- ^ "Electricity Supply". sotonopedia. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Garcke, Emile (1898). Manual of Electrical Undertakings. London: P. S. King & son.

- ^ a b "Mercenaria mercenaria". Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Joint Nature Conservation Committee. 25 April 2006. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ a b c Electricity Commissioners (1925). Electricity Supply - 1920-1923. London: HMSO. pp. 82–85, 314–319.

- ^ a b c Garrett, Frederick C., ed. (1959). Garcke's Manual of Electricity Supply. London: Electrical Press. pp. A-94, A-133.

- ^ Electricity Council (1987). Electricity Supply in the United Kingdom: a Chronology. London: Electricity Council. pp. 60–61. ISBN 085188105X.

- ^ CEGB Annual report and Accounts, 1961, 1962 & 1963

- ^ Electricity Commission, Generation of Electricity in Great Britain year ended 31st December 1946. London: HMSO, 1947.

- ^ CEGB Statistical Yearbook 1967

- ^ Hamilton, Keith (15 June 2014). "Inside Southampton Power Station". Southern Daily Echo. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- ^ CEGB (1972). CEGB Statistical Yearbook 1972. London: CEGB. pp. 10–11.