Reform Congregation Keneseth Israel (Philadelphia)

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Reform Congregation Keneseth Israel | |

|---|---|

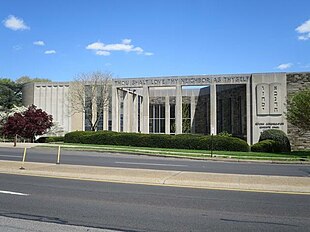

Keneseth Israel synagogue entrance | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Reform Judaism |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Synagogue |

| Leadership | Rabbi Benjamin P. David |

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | 8339 Old York Road, Elkins Park, Greater Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19027 |

| Country | United States |

Location just outside the city limits of Philadelphia | |

| Geographic coordinates | 40°05′09″N 75°07′38″W / 40.0859°N 75.1273°W |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Synagogue |

| Date established | 1847 (as a congregation) |

| Completed |

|

| Website | |

| kenesethisrael | |

Reform Congregation Keneseth Israel, abbreviated as KI, is a Reform Jewish congregation and synagogue located at 8339 Old York Road, Elkins Park, just outside the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in the United States. Founded in Philadelphia in 1847, it is the sixth oldest Reform congregation in the United States, and, by 1900, it was one of the largest Reform congregations in the United States. The synagogue was at a number of locations in the city before building a large structure on North Broad Street in 1891, until 1956 when it moved north of the city to suburban Elkins Park.

The congregation has been led by eight rabbis since its first rabbi commenced in 1861 – and most have been prominent both in the Reform Jewish movement and in other areas of American culture. Rabbi David Einhorn was the most prominent Jewish opponent of slavery when the Civil War began, and from that point on KI was known as the "Abolitionist Temple." Its third rabbi, Joseph Krauskopf was the founder of the Delaware Valley University[1] and was a friend of President Theodore Roosevelt. The fifth rabbi, Bertram Korn was the author of the leading book on Jewish participation in the American Civil War, served as chaplain in the Naval Reserves, and was the first Jewish Chaplain to achieve the rank of a Flag officer in any of the armed forces, when he became a Rear Admiral in 1975. The sixth rabbi, Simeon Maslin served as president of the Central Conference of American Rabbis from 1995 to 1997.[2] The current rabbi, Lance Sussman is an historian and the author of numerous books on American Jewish history.

Prominent members of the congregation include Judges Arlin Adams, Edward R. Becker, Jan E. DuBois, and Horace Stern, members of the Gimbel family, and businessmen Lessing Rosenwald, William S. Paley, Simon Guggenheim, and Walter Hubert Annenberg. Albert Einstein accepted an honorary membership in 1934.

Philadelphia's fourth synagogue, 1847-1855

[edit]In 1847 Julius Stern led in the creation of Keneseth Israel as a traditional German –Jewish Congregation. Stern and 47 other men seceded from an existing synagogue, Congregation Rodeph Shalom (the 3rd oldest in Philadelphia), to create the new congregation. Until the 1880s business meetings were conducted in German, and services were in both German and Hebrew. The new Congregation's ritual was initially based on traditional, Orthodox Jewish customs and practice. When first organized the synagogue hired a lay "reader," B.H. Gotthelf, rented space, and made plans to have burial plots in a local cemetery. The congregation established its first religious school 1849, with about 75 children learning Hebrew and Jewish ritual. In 1852 the congregation began to have sermons, which was a step away from traditional Orthodox Jewish ritual, but reflected the common Protestant worship that dominated the United States. At about this time the congregation also adopted the recently published Hamburg Prayer Book, which came out of the new Reform Movement in Germany. In 1854 KI purchased its first building, a former church on New Market Street, which was rededicated and consecrated as a synagogue. The re-purposing of religious edifices is common in America, as new immigrants acquire buildings that were built by other faiths. While KI did not yet have an ordained rabbi, Orthodox rabbis from other Congregations in Philadelphia participated in the re-consecration of the building.

German reform, 1855-1887

[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2023) |

After moving into its new building KI quickly purchased an organ, which marked its movement away from traditional orthodox Judaism, which did not have musical instrument or choirs at its services. In 1856 KI formally announced its affiliation with the Reform movement in Judaism, and took the name "Reform Congregation Keneseth Israel." That year KI produced its first published book, Gesänge zum Gebrauche beim Gottesdeinst der Reform-Gemeinde "Keneseth Israel" zu Philadelphia [Hymnal For the Order of Worship for Reform Community Keneseth Israel of Philadelphia].[3] The following year (1857) KI hired Solomon Deutsch, a prominent Reform leader from Posen, Germany to officiate at the Congregation. Although Deutsch was not an ordained rabbi, he moved KI further along on its road to Reform observance, by, among other things, abolishing separate seating for men and women, which is an obvious marker of the difference in worship between Orthodox synagogues and others in the United States and elsewhere. KI dismissed Deutsch in 1860 but the following year hired David Einhorn, an ordained Rabbi, who was one of the most prominent Reform leaders in the United States. Ironically in 1862 Deutsch moved to Baltimore, where he was Einhorn's successor at Har Sinai Congregation.

Einhorn

[edit]

David Einhorn (1809- 1879) was born in Diespeck, Bavaria on November 10, 1809. He emigrated from Germany in 1856 to become the Rabbi at Har Sinai Congregation in Baltimore,[4] which was the first Jewish congregation in the U.S. to affiliate with the Reform Movement. That year he published a 64-page prayer book pamphlet, for the use on Shabbat (the Jewish Sabbath) and for the three Biblical festivals, Sukkot, Passover, and Shavuot.[5] Two years later Einhorn published the first Reform prayer book in the United States, 'Olat tamid. Gebetbuch für israelitische Reform-Gemeinden (Baltimore, 1858). This book had an enormous impact on American Reform Judaism, and in addition to the Baltimore publication, it was printed and sold in New York.[6] Eventually the Olat tamid would evolve into the Union Prayerbook of the modern Reform Movement.[7] By 1860 KI had adopted this new prayer book.

While living in Baltimore, Einhorn was an outspoken opponent of slavery, which was politically problematic in Maryland, which at the time was a slave state with more than 87,000 slaves[8] In 1861 Einhorn's opposition to slavery became dangerous with secession and the beginning of the Civil War. In early January 1861 Dr. Morris Jacob Raphall, the rabbi at Congregation B'Nai Jeshurun in New York City gave and then published a sermon entitled the Bible View of Slavery,[9] which defended slavery under biblical law. Rabbi Raphall claimed he was "no friend to slavery in the abstract, and still less friendly to the practical working of slavery." But at the same time he claimed that "as a teacher in Israel" his role was "not to place before you my own feelings and opinions, but to propound to you the word of God, the Bible view of slavery."[10] However, much Raphall tried to explain his position, Southern secessionists and other supporters of slavery were delighted by his endorsement of a Biblical defense of slavery. Incensed, Einhorn delivered an antislavery sermon in German, and then published an English translation in his monthly journal Sinai,[11] refuting the Raphall's pamphlet. Einhorn's last paragraph (see box quote below) was about the relationship between ethics, religion, and the Bible:

I am no politician and do not meddle in politics. But to proclaim slavery in the name of Judaism to be a God-sanctioned institution—the Jewish-religious press must raise objections to this, if it does not want itself and Judaism branded forever. Had a Christian clergyman in Europe delivered the Raphall address—the Jewish-orthodox as well as Jewish-reform press would have been set going to call the wrath of heaven and earth upon such falsehoods, to denounce such disgrace and ... are we in America to ignore this mischief done by a Jewish preacher? Only such Jews, who prize the dollar more highly than their God and their religion, can demand or even approve of this!

This publication was both morally righteous and political dangerous. Threatened by a mob, which tried to tar and feather him on April 19, 1861, Einhorn, guarded by friends, fled to Philadelphia a few days later. In Philadelphia KI quickly hired him to be the Congregation's first ordained Rabbi. At KI, Einhorn continued to publish his periodical, Sinai. In 1862, with financial support from KI, he published a second edition of Olat Tamid,[12] which was printed in Baltimore and also in New York City.[13] In 1866 Einhorn moved to New York City, to accept the pulpit of Adath Yeshurun.

While Einhorn had denied any interest in politics, his pamphlet on slavery was in fact quite political and it dovetailed with KI's increasing social and political activism. In 1857 the Congregation had protested a treaty with Switzerland which was supposed to give citizens of both countries equality in travel and business opportunities, but in fact allowed Swiss Cantons to discriminate against American Jews. In 1860 the congregation sent money to help Jews facing persecution in Morocco. When the Civil War began, in April 1861, members of the small Congregation supported the war effort with money and their own sons. Isaac Snellenberg, whose parents had emigrated from Germany, lied about his age so that he could enlist, and died in the Peninsular Campaign in 1862 at the age of 16.[14] Col. Max Einstein, who would join KI after the War, commanded a Pennsylvania regiment at the first battle of Bull Run.[14]

Hirsch

[edit]

When Einhorn moved on to New York after the War, the Congregation offered a lifetime contract to Rabbi Samuel Hirsch (1815-1889), who was serving as the first Chief Rabbi of Luxembourg at the time. After Hirsch moved to Philadelphia he continued services in German, but other than that, his leadership moved KI towards greater Americanization and further reform. Hirsch instituted Sunday lectures (or sermons) which made the congregation look more like its Protestant neighbors, which held their service and had their sermons on Sunday. He abolished the use of yarmulkes or other head coverings for men during services and brought an egalitarian marriage ceremony to the congregation, with both men and women exchanging vows. His goal was to eliminate archaic practices that hindered his congregants from fully participating in American civil society. Along these lines, he helped create Jewish social service agencies and helped organize a branch of Alliance Israelite Universelle, a Paris-based international organization which was dedicated to fighting anti-Semitism and defending the "honor" of the Jewish community. In 1878 KI joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations[15] (UAHC), today called the Union for Reform Judaism, the national organization of Reform Congregations founded in 1873 by Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise. In 1886, when Hirsch was seventy years old, KI pressured him to retire. Unhappily he moved to Chicago where his son Emil G. Hirsch was the rabbi at Chicago Sinai Congregation. By this time Emil had married Mathilda Einhorn,[16] the daughter of KI's first rabbi, David Einhorn.[17]

American classical reform, 1887-1949

[edit]Krauskopf

[edit]

With the departure of Hirsch, KI conducted a national search for a new rabbi, ultimately offering its pulpit to Joseph Krauskopf in July 1887. At the time Krauskopf was the rabbi at Congregation B'nai Jehudah[18] in Kansas City, Missouri. Krauskopf served as rabbi from 1887 to 1923.

Krauskopf (1858-1923), like the two previous rabbis at KI, was a German speaking immigrant. Krauskopf had emigrated to the United States in 1872, at age 14, and quickly learned English. In 1875, at the age of 17, Krauskopf went to Cincinnati, where he was a member of the first class at the Reform Movement's recently opened rabbinical school, Hebrew Union College (HUC).[19] While at HUC Krauskopf published the Union Hebrew Reader (1881) which is commonly known as the First Union Hebrew Reader, the Second Union Hebrew Reader (1884), and Bible Ethics: A Manual of Instruction in the History and Principles of Judaism, According to Hebrew Scriptures (1884)[20] (full text[21]). While in Kansas City, Krauskopf was enormously popular within his synagogue and the larger Kansas City community. His public lectures attracted large audiences that extended well beyond the city's small Jewish community. Some of these lectureswere then published as books, such as Evolution and Judaism[22] and The Jews and Moors in Spain.[23] Additionally, he was involved in a wide range of civic activities, such as becoming a life-member of the board of the National Conference of Charities and Correction.[24][25] In 1885 he was a key organizer of a convention of reform Rabbis in Pittsburgh, known as the Pittsburgh Conference. Although only two years out of rabbinical school, he was elected vice-president of the Pittsburgh Conference, of which Isaac Mayer Wise was president. This conference wrote the Pittsburgh Platform, which became the defining statement of Reform Judaism at that time. Given Krauskopf's accomplishments, it was hardly surprising that KI recruited him, and it was equally unsurprising that the leadership of B'nai Jehudah attempted to prevent him from leaving. After some embarrassing communications, Krauskopf arrived in Philadelphia in late October 1887.

Krauskopf revolutionized KI. Under Krauskopf KI shifted from German to English for its board meetings, publications and services. He reintroduced Sunday services (which had waned in the last years under Hirsch), instituted confirmation at age sixteen for boys and girls, and eliminated the traditional bar mitzvah at age thirteen. In 1892 he created a library for KI that acquired more than 20,000 volumes under his leadership. Krauskopf also convinced the Synagogue to hire an assistant rabbi to accommodate the massive growth in members.

When Krauskopf arrived there were about 250 family and individual members at KI. Within a few years, in part because of Krauskopf's charisma and the popularity of his lectures, the Congregation had more than 400 families. In 1892 KI moved to a brand new building on North Broad Street (built under Krauskopf's leadership), with a sanctuary that provided seating for 1600 people. Among the national leaders at the dedication of this building were Simon Wolf, a Washington, D.C. lawyer, political leader, former diplomat, and the International President of B'nai B'rith and Rabbi Isaac Meyer Wise, who is usually considered to be the founder of the American Reform Movement. By the turn of the century membership had increased to more than a 1,000 families and there were at least 500 students in the religious school. KI was now one of the biggest (perhaps the biggest) synagogues in the nation. Throughout his tenure at KI Krauskopf gave weekly Sunday lectures to overflow crowds on history, science, ethics, politics, economics, theology, and the Bible. During his career at KI Krauskopf published more than a thousand pamphlet versions of these lectures.

In 1888, shortly after he arrived in Philadelphia, Krauskopf was instrumental in the creation of the Jewish Publication Society,[26] with KI giving early support the endeavor. In March, 1903, Krauskopf was elected director-general of the Isaac Meyer Wise Memorial Fund, and in July of the same year he became president of the Central Conference of American Rabbis, the main professional organization of reform rabbis.

Beyond the Synagogue, Krauskopf worked with religious leaders of other faiths, visited Russia to investigate discrimination and violence against Jews, and raised money for the creation of the National Farm School, which more than a century later became Delaware Valley University. Krauskopf visited Jewish settlements in Palestine, and supported the Zionist movement as a vehicle for the settlement of European Jews in Palestine. At the same time, however, he vigorously denied that American Jews had "dual loyalties," and was aggressively patriotic about his adopted homeland.

Shortly after the outbreak of the Spanish–American War in 1898, Krauskopf became a leader of the National Relief Commission, and was one of three special field commissioners sent to visit army camps in the United States and Cuba. While in Cuba, Krauskopf became friends with Col. Theodore Roosevelt and conducted services for the eight Jewish soldiers in Roosevelt's Rough Riders (the First United States Volunteer Cavalry). Krauskopf and Roosevelt would remain lifelong friends and when Roosevelt died, Krauskauf had a large stained glass window commissioned in his honor which remains today as a part of the entrance foyer in the Keneseth Israel synagogue in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania. Krauskopf's and KI's military and patriotic support continued during World War I when the congregation created special programs for servicemen stationed in Philadelphia or passing through the city on their way to the front. In 1917, James G. Heller who was the assistant rabbi at KI, took a leave of absence from that position in order to serve as a US Army chaplain.

In 1923 KI made Krauskopf a Rabbi for life, at full salary. This was a gesture of reverence for the spiritual leader who had made KI one of the most prominent and important congregations in the national reform Jewish world. Shortly after that vote Krauskopf passed away. After 36 years with one rabbi, KI now had to seek new leadership.

Fineshriber

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2023) |

Rabbi William Fineshriber served as rabbi from 1923 to 1949.

With the death of Rabbi Krauskopf, in June 1923, the associate Rabbi Abraham J. Feldman officiated at KI while the synagogue searched for a new senior rabbi. Later that year KI hired William H. Fineshriber (1878-1968), its first American-born senior Rabbi. Fineshriber was born in St. Louis, Missouri, where his father was a Reform rabbi. Fineshriber's father died at the age of 37, and at age 13 Fineshriber moved to Cincinnati where he attended high school and entered an eight-year program allowing him to simultaneously earn degrees from both the University of Cincinnati and Hebrew Union College. By 1900 he had graduated from both[27] and became the Rabbi at Temple Emanuel in Davenport, Iowa. In 1911 he moved to Congregation B'nai Israel in Memphis, Tennessee, where he was active in numerous community and social causes. He was strong advocate of women's suffrage and spoke out against lynching, and despite threats on his life, regularly denounced the Ku Klux Klan. Before large crowds he gave lectures in support of the right to study evolution, but shortly after he left Tennessee the state passed its infamous anti-evolution law that led to the Scopes "Monkey" Trial. In 1924 Fineshriber moved to Philadelphia to become the senior rabbi at KI.

At KI Finsshriber continued his social activism, inviting such notables as Margaret Sanger, the founder of the modern birth control movement, to speak at KI and making the Nobel prize winning physicist, Albert Einstein, an honorary member of the Congregation. Einstein spoke at KI's 90th anniversary celebration. Fineshriber was also nationally active in the movie industry, working with Hollywood leaders to adopt a "decency code" for the film industry. He also was involved in the labor arbitration, in Philadelphia and elsewhere. In settling the Aberle Stocking Mill strike he worked with Jewish leaders of the textile workers union and the Jewish managers and owners of the textile companies. In this sense, Fineshriber acted in the tradition of Rabbis settling disputes within their own community. Fineshriber's work led to a nationally accepted arbitration procedure for most of the textile industry.

Jewish world in crisis

[edit]More complicated was Fineshriber's response to the Zionism and the rise of Nazism. Reflecting the mainstream position of the Reform movement, Fineshriber supported the emigration of Eastern European Jews to what was then British controlled Palestine, but he did not support the creation of a Jewish state or believe that American Jews should emigrate there. He consistently argued that Jews were members of a religion, not a nationality, and thus KI accepted the formal position of the Reform Movement (as expressed through the Union of American Hebrew Congregations) to "disassociate itself completely from any controversy pertaining to political Zionism." Like all Jews, in the 1930s he was shocked and appalled by the rise of Nazism with its grotesque persecution of Jews, and some members of KI were actively associated holocaust rescue, especially Gil and Eleanor Kraus who rescued at least fifty German-Jewish children before World War II began.

Fineshriber's tenure at KI also reflected the evolving ritual of American Reform Judaism. He reintroduced Bar and Bat Mitzvah, Torah reading on Saturday and the Jewish High Holidays (Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur), restored the position of cantor, and added violin or cello to the congregation's musical services. During this period KI adopted the Union Prayer Book, which had been the official prayer book of the American Reform Movement. Ironically, this prayer book was based on the Olat Tamid, written by KI's first Rabbi, David Einhorn. The Union Prayer Book replaced the Sunday Service manual written by Rabbi Krauskopf, as well as the hymnal he had created.

During World War II KI provided worship services for thousands of soldiers and sailors who were stationed in Philadelphia, or passed through on their way to other posts. Organizations within KI (such as the Sisterhood and Men's Club) were involved in blood drives, the preparation of bandages, and the writing of letters to soldiers overseas. Collectively, the Congregation sold over a million dollars' worth of war bonds. In addition, KI provided worship space for Orthodox Jews who were refugees from Germany. Scores of members served in the military. One board member, who was a military officer assigned to the War Department in Washington, ultimately resigned his position at KI because it was simply impossible for him to commute back to Philadelphia for board meetings. About two dozen members who died in combat were memorialized at KI. Bertram Korn, who had his Bar Mitzvah in KI when Fineshriber reintroduced the ceremony, enlisted as a chaplain in the Navy during the war, serving with the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions in China.

At the end of the war, Fineshriber, as a national leader of the reform movement, opposed the creation of a Jewish state in British Palestine, which became Israel in 1948. Fineshriber, a leader among a highly visible minority of Reform Rabbis, resisted the idea of Jews being seen as a nation in need of their own state. He strongly believed that American Jews had to avoid being suspected of having dual loyalties. In essence, he saw himself as an American of the Jewish religion rather than a "Jewish-American." However, when Israel was created in 1948, he modified his anti-Zionist position recognizing the utility of Israel as a haven for Holocaust survivors and other Jewish refugees.

In 1947 Fineshriber had presided over the 100th anniversary celebration of KI, which included an address by Governor James H. Duff of Pennsylvania and Justice Horace Stern, a member of KI, who was also the first Jewish judge to serve on the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. In 1949, at age 71, Fineshriber retired, with title Rabbi Emeritus. Two years later, in 1951, the University of Pennsylvania awarded him an honorary Doctor of Laws degree. Fineshriber's successor was Professor Bertram Wallace Korn, who was teaching American Jewish History at Hebrew Union College where he had studied to become a rabbi and later earned a Doctorate in Hebrew letters under Professor Jacob R. Marcus.

Neo-reform, 1949-2001

[edit]Korn

[edit]Rabbi Bertram Korn served as Rabbi from 1949 to 1979.

Bertram Wallace Korn, (1918–1979), was a historian and rabbi. He attended the University of Pennsylvania, Cornell University and the University of Cincinnati, and received an M.H.L. degree from the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in Cincinnati (where he was ordained as a rabbi in 1943), Following his ordination he served as the rabbi at the Government Street Temple in Mobile, Alabama, but a year later, in 1944, Korn enlisted in the United States Navy as a lieutenant in the Chaplain's Corps. He served in China with the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions. After the War Korn would remain in the Naval Reserves, and in 1975, he was promoted to rear admiral in the Chaplains Corps, U.S. Naval Reserve. With this promotion Korn became the first Jewish chaplain to receive flag rank in any of the United States armed forces. When the War ended, Korn returned to Hebrew Union College to complete a Ph.D. in Hebrew Letters. While working on his doctorate, Korn was an assistant professor at HUC, where he offered the college's first course in American Jewish history. He also served as a special assistant to the president of the college.

In 1949 KI hired Korn to replace the retiring Rabbi Fineshriber, Korn would remain at KI there until his death in 1979.[1] (KI) in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In 1957, under Rabbi Korn's leadership, KI moved from its Broad Street location to a new building at the current address on Old York Road in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania. Korn wrote twelve books on American Jewish History, the most famous being American Jewry and the Civil War, in 1951. Other books by Korn include: I (1971); Benjamin Levy: New Orleans Printer and Publisher (1961); Jews and Negro Slavery in the Old South, 1789-1865 (1961); The American Reaction to the Mortara Case: 1858-1859 (1957); and The Early Jews of New Orleans (1969). Korn was also the president of the American Jewish Historical Society.

In 1951 KI agreed to sell the Broad Street Synagogue and other annex buildings to Temple University, in contemplation of moving to a new location. In 1957 the congregation completed the move to Elkins Park, a suburb north of Philadelphia. The new building incorporated many of the stained glass windows that had been in the Broad street building, including the commemorative window installed under the leadership of Rabbi Krauskopf after the death of his friend Theodore Roosevelt. The building also included a newly created series of windows by the well known artist Jacob Landau (which are discussed below). The move to Elkins Park reflected the growing suburbanization of American Jews in the post-War period. Suburbanization led to a dispersal of congregation members and an alteration in the traditional pattern of synagogues being part of compact communities. In response to these changing demographic patterns, Korn introduced radio broadcasts of KI services, which allowed members of his more geographically scattered congregation to hear services when they were unable to reach the synagogue.

In the 1970s Korn brought KI into active work on behalf of Jews trapped in the Soviet Union. This support of Russian Jewry was a modern version of Rabbi Krauskopf's concerns for Russian Jews in the 1890s.

In 1978 Korn formally retired from the Naval Reserve at a special Shabbat service at KI. Among those present were Admiral John O'Connor, the chief of Naval Chaplains who would later be more famously known as John, Cardinal O'Connor of New York. At this point Korn announced his planned retirement from KI, in 1980. However, the following year he died suddenly, and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Under Korn KI had achieved its largest number of members, with more than 1,800 families.

Landau windows

[edit]"The Prophetic Quest"[28] is the title of the ten stained glass windows designed by Jacob Landau and installed in the KI synagogue[29] in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania in 1974. They represent the prophets Abraham, Elijah. Amos, Hosea, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Second Isaiah, Job, and Malachi, and their messages.

Landau created the original drawings, Benoit Gilsoul[30] transcribed the original drawings into working cartoons, and the stained glass studio Willet Studios (Willet Hauser Architectural Glass) made the windows.

Maslin

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2023) |

Rabbi Simeon J. Maslin served as rabbi from 1979 to 1997.

After the death of Rabbi Korn, Rabbi Simeon J. Maslin (1931-) became the senior rabbi at KI. When he arrived he was already a distinguished Rabbinic leader, known in part for his public speaking and oratory. He was a leading voice in the reform movement against rabbinic officiation at interfaith weddings. This was an enormously contentious issue in the Reform Movement. Initially the Reform Movement followed Maslin's lead, but since about the year 2000 most (but not all) Reform Rabbis have been willing to perform such marriages.

As a major proponent of traditional ritual, Maslin brought more Hebrew to the services and reintroduced the traditional custom of men wearing a skullcap (Yarmulke) during services. Since the 19th century KI had actually prohibited the use of Yarmulkes. While at KI he also served as the president of the Central Conference of American Rabbis, the organization of North American Reform Rabbis. Maslin was a committed supporter of Israel and instituted the sending of conformation classes to Israel. At the same time, he was one of the leading critics of Israel for its refusal to accept Reform Judaism.

In 1986, Rabbi Maslin published an important contribution to Reform Jewish thought, Gates of Mitzvah: Shaarei Mitzvah: A Guide to the Jewish Life Cycle.[31] In 1998, shortly after his retirement, Maslin published What We Believe ... What We Do ... A Pocket Guide for Reform Jews.[32]

Temple Judea Museum

[edit]In 1982–1983, a smaller Reform congregation, Temple Judea, located on Old York Road in North Philadelphia, merged into KI.[33]

Temple Judea had hosted a significant museum of Judaica, historical materials of the synagogue, photographs, and other items of interest.[34] In the early 1960s KI had likewise created its own museum, to house the many artifacts and works of art it had acquired over the previous century.

In 1984,[35] the two museums merged into the Temple Judea Museum[36] with the art and historic object collections of Temple Judea and Reform Congregation Keneseth Israel, forming a much larger and more important museum. With over 4000 items focused on the observances of Judaism, the museum represents multiple historic eras and many countries of the world. Special exhibitions are often presented which include an emphasis on separate labeling for children so that families can independently enjoy the exhibit. The museum regularly draws visitors and groups from all religious denominations. The director/curator, as-well-as the volunteers, include in their museum tours the collection of stained glass windows "The Prophetic Quest" by Jacob Landau.

21st century

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2023) |

Sussman

[edit]

Lance J. Sussman has served as rabbi since 2001.

With the retirement of rabbi Maslin, KI recruited Sussman (b. 1954) to be its senior rabbi. Sussman was born and raised in Baltimore, graduated in three years from Franklin and Marshall College (where he was elected to Phi Beta Kappa), and then received a rabbinic degree from HUC and remained to earn a Ph.D. in history in American Jewish history. Sussman's dissertation was later published as Isaac Leeser and the Making of American Judaism (1995). Ironically, Leeser had been the leader of the Philadelphia Jewish Community at the time KI was formed in 1847.

Prior to arriving at KI, Sussman was a tenured professor in history at the State University of New York at Binghamton as well as the rabbi at Temple Concord,[37] a Reform congregation in Binghamton, New York. Sussman is a well-known scholar of American Jewish history. In addition to his book on Leeser, he is the author of Sharing Sacred Moments (1999),[3] and a co-editor of Reform Judaism in America: A Biographical Dictionary and Sourcebook (1993)[4] and New Essays in American Jewish History (2009) At KI he has continued to publish in historical work while also actively participating in various aspects of the Reform Movement. He has also been heavily involved in interfaith organizations in Philadelphia. Like Rabbi's Krauskopf and Korn, Sussman was active in the movement to help Jews escape the Soviet Union and more recently has been involved in efforts to reach out to the small Jewish community in Cuba. Under Sussman's leadership KI developed youth exchange programs between KI teenagers and teenagers in Germany.

While a full-time rabbi, Sussman has taught American Jewish History at Princeton, Temple University, and Delaware Valley University, and been an active participant in the creation of the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia and the Center for Jewish History in New York.

Notable Assistant Rabbis

[edit]- Rabbi Malcolm H. Stern (1941-1947)

Notable members

[edit]- Elliot Abrams (1947-), meteorologist on KYW Newsradio 1060 from 1971 - 2014; co-inventor of AccuWeather RealFeel Temperature

- Judge Arlin Adams (1921-2015), US Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit; President of KI Congregation (1955-1957)

- Walter Hubert Annenberg (1908-2002), US Ambassador, publisher and philanthropist

- Judge Edward R. Becker (1933-2006), US Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

- Norman Fell (1924-1998), actor

- Samuel S. Fleisher (1871–1944), manufacturer, art patron, and philanthropist

- Gimbel Brothers, founders of the eponymous department store, and their associated families

- Albert M. Greenfield (1884-1967), real estate developer

- Guggenheim Family including Simon Guggenheim (1792-1869), Meyer (1828-1905), Benjamin (1865-1912), and (John) Simon (1867-1941)

- Rabbi Bertram Korn (1918-1979), Senior Rabbi at Reform Congregation Keneseth Israel, Rear Admiral in Navy Chaplaincy Corps, Historian

- Joseph L. Kun (1884-1961) - Common Pleas Court Judge

- William S. Paley (1901-1990), established Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS)

- Lessing Rosenwald (1891-1979), President and chairman of the board of Sears, Roebuck & Company, leading philanthropist, art collector

- Snellenburg family, clothing manufacturers[38]

- Horace Stern (1878-1969), Chief Justice of Pennsylvania Supreme Court

- Dr. Andrew Weil (1942-), medical doctor, Head of AMA Alternative Medicine - KI Confirmation Class '58

References

[edit]- ^ "Former Presidents". Delaware Valley University. Retrieved October 10, 2015.

- ^ Central Conference of American Rabbis. "Past Presidents Council". Central Conference of American Rabbis. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ Wachs, Sharona R, ed. (1856). Gesänge zum Gebrauche beim Gottesdeinst der Reform-Gemeinde "Keneseth Israel" zu Philadelphia (American Jewish Liturgies: A Bibliography of American. Jewish Liturgy from the Establishment of the Press in the Colonies through 1925 (Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 1997) ed.). Philadelphia: R. Stein. pp. Page 46, Item # 59. ISBN 0-87820-912-3.

- ^ Blum, M. "Find A Congregation". ReformJudaism.org. URJ. Retrieved October 10, 2015.

- ^ Einhorn, David (1856). Wachs, Sharona R (ed.). Gebetbuch für israelitische Reform-Gemeinden: im Verlad der Har-Sinai Gemeinde zu Baltimore (Americacn Jewish Lituergies: A Bibliography of American Jewish Liturgy from the Establishment of the Press in the Colonies through 1925 (Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 1997) ed.). New York: H. Frank. pp. Page 46, Item # 58. ISBN 0-87820-912-3.

- ^ Wachs, Sharona R (1997). Americacn Jewish Lituergies: A Bibliography of American Jewish Liturgy from the Establishment of the Press in the Colonies through 1925. Cincinnati, OH: Hebrew Union College Press. pp. 48–48, items 76-80. ISBN 0-87820-912-3.

- ^ Grand, Samuel (1962). David Einhorn: The Father of the Union Prayerbook. New York, NY: Union of American Hebrew Congregations.

- ^ Gibson, Campbell; Jung, Kay (September 2002). HISTORICAL CENSUS STATISTICS ON POPULATION TOTALS BY RACE, 1790 TO 1990, AND BY HISPANIC ORIGIN, 1970 TO 1990, FOR THE UNITED STATES, REGIONS, DIVISIONS, AND STATES (PDF). Washington DC: U.S. Census Bureau. p. table 35.

- ^ Raphall, Dr. MJ. "The Bible View of Slavery". Jewish-American History Foundation. Jewish-American History Documentation Foundation. Retrieved October 10, 2015.

- ^ Finkelman, Paul (2003). Slavery Defended: Proslavery Thought in the Old South. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's. ISBN 978-0312133276.

- ^ Einhorn, David; Kohler, Mrs. Kaufmann. "David Einhorn's Response to "A Biblical View of Slavery"". Jewish-American History Foundation. Jewish-American History Documentation Foundation. Retrieved October 10, 2015.

- ^ Einhorn, David (1862). 'Olat tamid. Gebetbuch für israelitische Reform-Gemeinden (2. Aufl. ed.). C.W. Schneidereith.

- ^ Wachs, Sharona R. (1997). Americacn Jewish Lituergies: A Bibliography of American Jewish Liturgy from the Establishment of the Press in the Colonies through 1925. Cincinnati, OH: Hebrew Union College Press. p. 51, item 103. ISBN 0-87820-912-3.

- ^ a b Finkelman, Paul; Sussman, Lance J. (August 3, 2015). "Online Synagogue Archives: The Future of American Judaism's Past". Huffington Post Religion. TheHuffingtonPost.com. Retrieved October 10, 2015.

- ^ "History". Union for Reform Judaism. Retrieved October 10, 2015.

- ^ Silverman, Linda. "Matilda Hirsch (Einhorn)". Geni. Geni.com. Retrieved October 11, 2015.

- ^ "Dr. Emil G. Hirsch of Chicago Sinai Congregation Is Dead". Daily Jewish Courier. No. IV, III C. Jewish Daily Courier. January 8, 1923. Retrieved September 7, 2015.

- ^ "History". The Temple, Congregation B'nai Jehudah. Retrieved September 7, 2015.

- ^ "WHY HUC-JIR?". Hebrew Union College. Jewish Institute of Religion. Retrieved October 11, 2015.

- ^ Krauskopf, Joseph; Berkowitz, Henry (1884). Bible ethics : a manual of instruction in the history and principles of Judaism, according to the Hebrew scriptures. Cincinnati, Ohio: Bloch. OCLC 24197325. Retrieved September 6, 2015.

- ^ Krauskopf, Joseph (1884). Bible ethics : a manual of instruction in the history and principles. Bloch and Co. Cincinnati. Retrieved September 7, 2015 – via catalog.hathitrust.org/.

- ^ Krauskopf, Joseph (1887). Evolution and Judaism. Kansas City, MO: Berkowitz & Co.

- ^ Krauskopf, Joseph (1886). The Jews and Moors in Spain (reprint available: Kessinger Publishing, LLC (September 10, 2010) ed.). Kansas City, MO: Berkowitz & Co. ISBN 1163470961.

- ^ "National Conference of Charities and Correction". The Social Welfare History Project. January 21, 2011. Retrieved September 7, 2015.

- ^ "National Conference on Social Welfare Proceedings (1874-1982)".

- ^ "The Jewish Publication Society".

- ^ Kalin, Berkley (1997). "A Plea for Tolerance: Fineshriber in Memphis". In Bauman, Mark; Kalin, Berkley (eds.). The Quiet Voices: Southern Rabbis and Black Civil Rights, 1880s to 1990s. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-0892-6.

- ^ Korn, Bertram (August 21, 1974). The Prophetic Quest. Philadelphia, PA: Harrison Color Process.

- ^ ""The Prophetic Quest" the Stained Glass Windows of Jacob Landau – Reform Congregation Keneseth Israel".

- ^ Gilsoul, W. "Bibliography". Benoit Gilsoul, Artist. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- ^ Maslin, Simeon J. (September 25, 1986). Gates of Mitzvah: Shaarei Mitzvah: A Guide to the Jewish Life Cycle. New York, NY: CCAR Press. ISBN 978-0916694531.

- ^ Maslin, Simeon; Schlinder, Alexander; Merians, Melvin (1993). What We Believe-- What We Do--: A Pocket Guide for Reform Jews. Indiana University: UAHC Press. ISBN 9780807405314.

- ^ Silverman, Erica (July 1, 2019). "'Synagogues of Philadelphia' Traces Jewish History Through Synagogues". Jewish Exponent. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- ^ Needelman, Joshua (September 20, 2018). "Temple Judea Museum Exhibits Historic Photos". Jewish Exponent. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- ^ "Temple Judea Museum". Eastern Standard. Jewish Exponent. November 7, 2015. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- ^ "Temple Judea Museum – Reform Congregation Keneseth Israel".

- ^ "Temple Concord The Reform Synagogue of Binghamton". www.templeconcord.com. Retrieved November 24, 2015.

- ^ "Manufacturers of Boys' Clothing: Snellenburg Clothing Co. (United States)". Historical Boys' Clothing. HBC. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

External links

[edit]- Classical Reform Judaism

- German-Jewish culture in Pennsylvania

- Jewish German history

- Jews and Judaism in Pennsylvania

- Organizations based in Philadelphia

- Reform synagogues in Pennsylvania

- Religious buildings and structures in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania

- 1847 establishments in Pennsylvania

- Jewish organizations established in 1847

- Synagogues completed in 1956

- 20th-century synagogues in the United States

- Synagogues in Pennsylvania