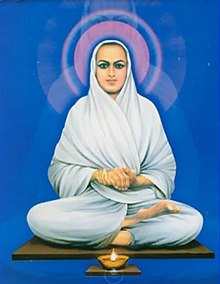

Ramalinga Swamigal

Ramalinga Swamigal | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 5 October 1823 |

| Disappeared | January 30, 1874 (aged 50) Mettukuppam, Vadalur, Cuddalore district, Tamil Nadu |

Thiruvarutprakasa Vallalār Chidambaram Ramalingam (5 October 1823 – 30 January 1874), also known as Vallalār, Ramalinga Swamigal and Ramalinga Adigal, was one of the known Tamil saints and a notable Tamil poet of the 19th century. He belongs to a line of Tamil saints known as "gnana siddhars" (gnana means 'higher wisdom').[1]

Ramalinga ventured to eliminate the caste in India.[2] To that end, he founded a group known as "Samarasa Suddha Sanmarga Sathiya Sangam",[3] which spread not only due to his theoretical teachings but mainly due to his practiced lifestyle, which is an inspiration for his followers. According to Suddha Sanmarga, the prime aspects of human life should be love connected with charity and divine practice leading to achievement of pure knowledge.

Ramalinga espoused the veneration of the radiant flame emanating from a lit lamp, not as a deity unto itself, but rather as a symbol representing the enduring omnipotence of the Divine, as opposed to the adoration of statues within a monotheistic framework.[4]

Early life

[edit]Ramalingam's[note 1] parents were Ramayya Pillai and Chinnammai of Vellalar caste. She was his sixth wife, as all his previous wives had died childless and in quick succession. They were a family in Marudhur, a village in the old South Arcot district, near Chidambaram. Ramalingam was their fifth and youngest child. The older ones were two sons, Sabhapati and Parasu Rāman; and two daughters, Sundarammal and Unnamulai.

Childhood and divine experiences

[edit]When Ramalingam was five months old, his parents brought him to the Chidambaram Natarājar Temple. The infant was joyous while the priest was offering Deepa Aradhana (adoration by a lighted lamp being brought close to the vigrahams); this was perceived by Ramalingam as a deep spiritual experience. In later years, he said of the experience: "No sooner the Light was perceived, happiness prevailed on me", and "The sweet nectar was tasted by me as soon as the Arut Perum Jothi (Divine Light of Grace) became visible".[5]

In 1824, his father died. Following this, his mother moving to her mother's residence at Chinna Kāvanam, Ponneri. Ramalingam was a small child when he and his mother relocated to Chennai in 1826, where they lived with his eldest brother Sabhapati and his wife Pāppāthi at 31/14 Veerasamy Pillai Street in the Sevenwells area.[note 2]

After Ramalingam reached five years of age, Sabhapati initiated his formal education. However, uninterested in his education, Ramalingam instead preferred trips to the nearby Kandha Kottam Kandha Swāmi Temple.[note 3] Sabhapati thought that the child needed punishment as a form of discipline, and he told his wife not to give Ramalingam his daily meal. His kind sister-in-law, however, secretly gave him food and persuaded him to study seriously at home. In return, Ramalingam asked for his own room, lighted lamp and mirror. He placed the light in front of the mirror and meditated by concentrating on the light. He miraculously saw a vision of the Lord Muruga. Ramalingam said: "The beauty endowed divine faces six, the illustrious shoulders twelve."[7]

At one time, Ramalingam had to replace his elder brother Sabhapati at an Upanyāsam (religious stories) session as upāsakar. His great discourse on verses from the Periya Purānam, an epic poem by Sekkizhar about the saintly '63 Nāyanārs', was appreciated by the devotees as being given by a very learned scholar. Ramalingam's mental and spiritual growth progressed rapidly. Ramalingam gave thanks to the Divine by saying: "Effulgent flame of grace, that lit in me intelligence, to know untaught."[8] Ramalingam evolved in his spiritual journey from being a devout devotee of Lord Shiva to worshiping the formless.

Ramalingam renounced the world at the young age of thirteen, but he was forced to marry his niece (on his sister's side). Legends say that the bridegroom during his first night after marriage was reading devotional works like the Thiruvāsagam. He was not interested in money, and it is said that in later life he reduced or ignored eating and sleeping. But he seemed fit in body,[citation needed] which was believed to be due to his supposed "physical transformation".

Teachings

[edit]

Ramalinga left Chennai in 1858. First, he went to Chidambaram where he had a debate with Kodakanallur Sundara Swāmigal. At the request of one Rāmakrishna Reddiyar,[who?] he went to his house at Karunguzhi (near Vadalur) and stayed there for nine years. He was against the caste system because of the adverse impacts it had on society. Towards that end, he started guild of devotees called the "Samarasa Vedha Sanmarga Sangam" in 1865. In 1872, it was renamed "Samarasa Suddha Sanmarga Sathya Sangam",[3] meaning "Society for pure truth in universal self-hood". Ramalinga was influenced by Valluvar and was drawn towards the teachings of the Tirukkural from a young age. He soon started teaching its message by conducting regular Kural classes to the masses.[9] He vowed to follow the Kural's morals of compassion and non-violence and continued emphasizing non-killing and meatless diet throughout his life by his concept of Jeeva Karunyam ('compassion for living beings'[1]).[10]: 39–42 [11]: 96 He said:

When I see men feeding on the coarse and vicious food of meat, it is an ever-recurring grief to me.[12]

In 1867, Ramalinga established a facility named "The Sathya Dharma Salai"[13] in Vadalur for serving free food to the poor. On the inaugural day, he lit the fire of the stone stove, with a declaration that the fire be ever alive and the needy shall be fed forever.[14][1] The facility, still in existence and run by volunteers, continues to serve free food to all people, without any caste distinction.[15] The land for the facility was donated by kind, generous people, and visitors can view the registration documents.[1]

On 25 January 1872, Ramalinga opened the "Sathya Gnana Sabhai" (Hall of True Knowledge) at Vadalur. This secular place is not a temple; there are no offerings, and no blessings are given. It is open to people of all castes except those who eat meat, who are only allowed to worship from the outside. The oil lamp lit by Ramalinga is kept perpetually burning. Ramalinga himself wrote in detail about the pooja to be performed in Gnana Sabhai—visitors below 12 or above 72 years of age alone were expected to enter Gnana Sabhai and do poojas.[1][16]

Within the complex are seven cotton fabric screens, representing the seven factors that prevent a soul from realizing its true nature. The entire complex is bound by a chain with 21,600 links, said to represent '21,600 inhalations'[17] by a normal human being. He said the intelligence we possess is Maya intelligence, which is not the true and final intelligence. The path of final intelligence is Jeeva Karunyam.[1]

Vallalār (Ramalinga) advocated a casteless society, and condemned inequality based on birth. He was opposed to superstitions and rituals.[1] He forbade killing animals, even for the sake of food. He advocated feeding the poor as the highest form of worship.[1] He also forbade idol worship, as he is historically said to have strongly opposed idols of Hindu gods and those made of himself by his followers. His rejection of idol worship was based on his belief in a formless, universal divine presence, rather than devotion to physical representations of God.

Vallalār advocated a spiritual path free from ritualistic practices, superstitions, and reliance on physical idols. His teachings emphasized compassion, love for all beings, and the pursuit of enlightenment, which he felt could not be achieved through the worship of idols or rituals. He encouraged his followers to focus on the formless divine and inner spirituality, rather than external symbols.[1]

One of the main teachings of Ramalinga is "Service to Living Beings is the path of Liberation (Moksha)".[1] He declared that death is not natural, and that life's first priority should be to fight death. He declared religion in itself a darkness.[citation needed] He said God is "Arut Perum Jothi" (Divine Light of Grace), the personification of grace or mercy and knowledge, and that the path of compassion and mercy is the only path to God.[1][18] Today, there are spiritual groups spread out all over the world who practice his teachings and follow the path of Arut Perum Jothi.

Literary works

[edit]As a musician and poet, Ramalinga composed 5,818 poems teaching universal love and peace, compiled into 'Six Thiru Muraigal', which are all available today as a single book called Thiruvarutpa[19] ('holy book of grace'). He composed the Veeraraghva Panchakam dedicated to Veeraraghava Perumal located in Tiruvallur.[20]

Other works of his include the Manumurai Kanda Vāsagam,[21] which describes the life of Manu Needhi Cholan, and Jeeva Karunya Ozhukkam,[22] which emphasizes compassion towards all sentient forms and insists on a plants-only diet.

Songs set to music

[edit]- Thiruvarutpa songs of Rāmalinga Swāmigal are sung in concerts, and now at least 25 songs (in Thiruvarutpā Isai Mālai) are given with swara-tāla notation.

- Thāyāgi thandhaiyumai (Hamsadhwani), Idu nalla tharunam (Shankarābharanam)

- Varuvar azhaithu vadi (Begada) and Thaen ena inikkum.

Some of his songs were set to music by Sīrkāzhi Govindharājan.[23]

Disappearance

[edit]On 22 October 1873, Ramalinga raised the 'flag of Brotherhood'[clarification needed] on his one-room residence Siddhi Valāgam in Mettukuppam.[24] He gave his final lecture—about spiritual progress and the "nature of the powers that lie beyond us and move us"—and recommended meditation using the lighted lamp from his room, which he then kept outside.

On 30 January 1874, Ramalinga entered the room, locked himself inside and told his followers not to open it. After opening, he said, he would not be found there. (He will be "united with nature and ruling the actions of 'all of the alls'," as told in his poem Gnana Sariyai). His seclusion spurred many rumors, and the government finally forced the doors open in May. The room was empty, with no clues. In 1906, records about his disappearance[25] were published in the South Arcot District's Madras District Gazetteers. Recent scholarship has noted how his disappearance bears a striking resemblance to the Rainbow body phenomenon.[26]

Postage stamp

[edit]The then-chief minister of Tamil Nadu M. Karunanidhi released postage stamps depicting Ramalinga on 17 August 2007.[27] After that, writ petition was submitted against the portrayal of Ramalinga with 'Thiru Neeru' (sacred ash) on his forehead. The Madras High Court declined to entertain that writ petition.[28]

In popular culture

[edit]Two biographical films were made about Ramalinga Swamigal.

| Year | Film | Actor | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1939 | Jothi | K. A. Muthu Bhagavathar | Lost film |

| 1971 | Arutperunjothi | Master Sridhar | Young Ramalingam |

| A. P. Nagarajan | Adult Ramalingam |

To commemorate Vallalar's 200th birth anniversary in 2022, a mosaic art piece was created using more than 5,000 small pieces of paper.[29][30][31]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ 'Ramalingam' was his given, pre-monastic name.[1]

- ^ The locality where he lived has been renamed 'Vallalār Nagar'.[citation needed]

- ^ Ramalingam composed 'Deiva Mani Malai' at this temple. Today, this temple has a hall called the Mukha Mandapam, which contains an idol of Sri Rāmalinga Swāmigal,[6] as well as Sarva Siddhi Vinayakar, Meenakshi Sundareswarar, Idumban, and Pamban Swāmigal.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Ramalinga Swamigal". My Dattatreya. Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- ^ Book Review by "The Hindu" on Vallalār Rāmalinga adigal varalaru

- ^ a b Details on Samarasa Suddha Sanmarga Sathiya Sangam [permanent dead link]

- ^ Alayam: The Hindu Temple; An Epitome of Hindu Culture; G.VenkataRamana Reddy; Published by Adhyaksha; Sri Rāmakrishna Math; ISBN 978-81-7823-542-4; Page 52

- ^ Arutperunjothi Archived 2008-09-16 at the Wayback Machine, Tamil Nadu Text books online

- ^ Dinamalar newspaper- Kandha kottam photos

- ^ Devnath, Lakshmi (2 February 2001). "Compassion is the essence of Saint Rāmalingam's philosophy". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 7 January 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Early life of Saint Vallalār[permanent dead link]

- ^ Kolappan, B. (3 October 2018). "First printed Tirukkural to be republished after 168 years". The Hindu. Chennai: Kasturi & Sons. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ N. V. Subbaraman (2015). வள்ளுவம் வாழ்ந்த வள்ளலார் [Valluvam Vaalndha Vallalar]. Chennai: Unique Media Integrators. ISBN 978-93-83051-95-3.

- ^ M. P. Sivagnanam (1974). திருக்குறளிலே கலைபற்றிக் கூறாததேன்? [Why does the Tirukkural not speak about art?]. Chennai: Poonkodi Padhippagam.

- ^ ""The Hindu" article on Vallalār". Archived from the original on 7 January 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Image of Sathya Dharma Salai

- ^ Prasad, S. (8 September 2022). "At Sathya Dharma Salai, the homeless are fed for the past 155 years". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ "Vallalar, practical philosopher". The Hindu. 4 May 2022. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ Details about the seven veils described by Vallalār Archived 2011-04-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Jnanarnava Tantra," Chapter Twenty One Archived 2006-04-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Beyond philosophy". The Hindu. 18 May 2022. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ Tamil Nadu Public service commission included Thiru arut pa in syllabus

- ^ "வீரராகவர் போற்றிப் பஞ்சகம் / Vīrarākavar pōṟṟip pañsakam - திரு அருட்பா, திருவருட்பா , Vallalar, வள்ளலார் , Ramalinga Adigalar , Thiru Arutprakasa Vallalar , தயவு , திருஅருட்பிரகாச வள்ளலார், சிதம்பரம் இராமலிங்கம் , சமரச சுத்த சன்மார்க்க சத்திய சங்கம் , VallalarSpace , ThiruArutpa , Thiruvarutpa , அருட்பெருஞ்ஜோதி தனிப்பெருங்கருணை".

- ^ Manumurai Kanda Vāsagam Archived 2011-04-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Details on Jeeva Karunya Ozhukkam Archived 2011-07-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sirkazhi Govindarajan from "The Hindu" newspaper

- ^ "Compassion is the essence of his philosophy". The Hindu. 2 February 2001. Archived from the original on 7 January 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Engraved stone in Vadalur (image) about the Madras District Gazette's note describing Rāmalingam's disappearance on 30 January 1874.

- ^ Tiso, Francis (2016). Rainbow body and resurrection: spiritual attainment, the dissolution of the material body, and the case of Khenpo A Chö. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books. pp. 12–17. ISBN 978-1-58394-795-1.

- ^ commemorative postage stamp on Vallalār Archived 2010-12-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Writ petition against Vallalar stamp rejected". The Hindu. 6 October 2007. Archived from the original on 30 January 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

- ^ "5,000 பேப்பர் துண்டுகளில் வள்ளலார் உருவம் அமைப்பு". 6 October 2022.

- ^ "ஓசூரில், வள்ளலாரின் 200 வது பிறந்த நாளையொட்டி மொசைக் ஆர்ட்டில் அவரது உருவத்தை வடிவமைத்த தனியார் நிறுவன ஊழியர்". 5 October 2022.

- ^ "5,000 பேப்பர் துண்டுகளில் வள்ளலார் உருவம் அமைப்பு". 5 October 2022.

- வடலூர் வள்ளலார் தைப்பூச ஜோதி தரிசனம்: எப்போது, எங்கு, எப்படி?

- Thiru Arutprakasa Vallalar Ramalinga Swamigal, or Ramalinga Adigal, Thiruvarutpa was written by - Ramalinga Swamigal. Vallalar Songs

Further reading

[edit]- Annamalai University's complete compilation of Thiruvarutpa in all six thirumurai in 10 Volumes Third edition of Thiruvarutpa released

- Srilata Rāman. "The Spaces In Between: Rāmalinga swāmigal (1823-1874), Hunger, and Religion in Colonial India," History of Religions (August 2013) 53#1 pp 1–27. DOI: 10.1086/671248

- Arut Prakasa Vallalār, the Saint of Universal Vision by V.S. Krishnan, published by Rāmanandha Adigalar Foundation, Coimbatore 641006

- Richard S. Weiss. 2019. The Emergence of Modern Hinduism: Religion on the Margins of Colonialism. California: University of California Press. [1]