Behind the Scenes in Slaughter-Houses

Behind the Scenes in Slaughter-Houses is a 1892 pamphlet on animal slaughter by H. F. Lester.[1]

Cover page | |

| Author | H. F. Lester |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Animal slaughter |

Publication date | 1892 |

| Media type | Print (pamphlet) |

| Pages | 19 |

| OCLC | 1116272431 |

| Text | Behind the Scenes in Slaughter-Houses at Wikisource |

Background

[edit]

Horace Francis Lester was born in 1853 in Bombay. He was the son of Frederic William Lester, who was a Major-general of the Bombay Artillery. Lester attended the University College in Oxford and became a barrister-at-law in 1879. Professionally, he made several legal writings, and was a contributor to the weekly satire magazine Punch. He also wrote several fictional works, including the 1887 parody Ben D'Ymion, the 1888 murder mystery Hartas Maturin, and the 1888 future war novel The Taking of Dover, before writing the pamphlet Behind the Scenes in Slaughter-Houses. He died four years after the publication, in 1896.[2]

The representative of the Humanitarian League, which published Lester's exposé, Reverend John Verschoyle, was also a member of the Model Abattoir Society, a council that Lester was the founder of.[3] On the concealment of the activities within the slaughterhouse, it was reported that the public had condemned the "pariah class" slaughtermen and that the "lads and little boys" had become curious, peering through the fences and banging at the doors, at establishments in Deptford and Islington, among others.[3][4]

This led Lester to write the slaughterhouse exposé, which he justified because he believed that "meat-eaters had a moral obligation to understand the "demoralization of character" that was a necessary step in the provision of meat," according to the cultural historian and food writer Paula Young Lee in her 2008 work, Meat, Modernity and the Rise of the Slaughterhouse.[5] For his contributions to writing on the subject of London slaughterhouses, Henry S. Salt, a president of the Vegetarian Society, refers to Lester as an expert in his 1921 autobiographical work, Seventy Years Among the Savages.[6]

Publication

[edit]

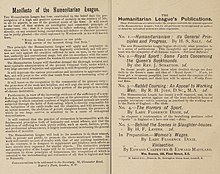

The 5 x 8" pamphlet is 19 pages in total length and was printed by William Reeves, at 185 Fleet Street, E. C., London in 1892.[7] Following the title page, the pamphlet includes the "Manifesto of the Humanitarian League," which expresses that the league works for the cessation of "suffering, directly or indirectly, on any sentient being." Included in the manifesto is an excerpt from the English Romantic poet William Wordsworth's poem "Hart-Leap Well."[8]

Behind the Scenes in Slaughter-Houses was issue number five of the Humanitarian League's "Pamphlet Series" publications.[9] The cost for one issue in the year of publication was 2 pence, and it was also the cost in 1896.[9] The final page in the pamphlet is a listing of the Humanitarian League's Publications, which was the first five issues, and the announcement of two which were in preparation.[10]

During the Humanitarian League's annual meeting, on March 16, 1893, Lester gave an account of the progress of slaughterhouse reform, following the publication of the pamphlet.[11] Copies of Behind the Scenes in Slaughter-Houses in microfilm format are available at university and public libraries in the United States, England, Ireland, the Netherlands, and Germany.[12]

Content

[edit]

The pamphlet is divided into three sections; namely "Behind the Scenes in Slaughter-Houses," "Humane Inventions for Slaughtering," and "Legislative Interference."

The opening to Behind the Scenes in Slaughter-Houses gives a quotation from Irish historian and political essayist William Edward Hartpole Lecky, who writes that the repugnance for the butcher trade has "simply ceased," adding that their work "has no place in their emotions or calculations." Lester then observes that "the ordinary human [...] shrinks instinctively from shedding the blood of one of the lower animals[,] in a community removed several steps from mere barbarism."[13] This is further indicated by the fact that "the sight and smell of blood [...] produces a feeling of oppression and nausea on any human being who enters the building."[14] He notes that with meat-eating, one must accept a "demoralization of character," as a result from the animals that must be killed, "whatever consequent suffering to them, and [the] degradation of the unfortunate butcher class."[15]

Lester suggests, that since "meat is not only not necessary, [and] injurious," then that the establishments could be converted into "wholesome receptacles for grains and fruit."[16] According to the medical authorities, diseases, such as tuberculosis, "appears to be impossible to prevent [and are] readily transmissible by eating the meat or drinking the milk of such animals."[4] Finally, in this section, Lester details several instances of private slaughter-houses operating in poor conditions, as well as reprinting the notes of three public slaughter-houses which were in a similar, destitute condition.[17]

The following, two shorter sections include a listing of several newly available methods for humane slaughtering. He also recounts the efforts of Parliament which had been devoted to providing the humane treatment of animals in slaughter-houses, as well as the minimization of dangers to public health incidental to such places.[18]

Response from the slaughtermen

[edit]In the pamphlet, Lester refers to the killing floor operators as "unclean creature[s]," asserting that the ranks of slaughtermen are composed of "the dregs of the population," who know that the butcher trade is "a nasty one, only bearable from lack of other employment and the good wages earned." This prompted one of the slaughtermen to reply:

"People don't treat me as an unclean creature that I know of; and as to talking about the "deep degradation of the nature of the whole class of men," I can tell him that he does misrepresent me and others and that I do my duty as well and am quite as honest as this vegetarian agitator, who pretends he only wants private slaughterhouses abolished, while all the while he wants to stop meat-eating all together... We are not even now "dregs" and never were."[19]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ MacLachlan, Ian (2007). "A bloody offal nuisance: The persistence of private slaughter-houses in nineteenth-century London". Urban History. 34 (2): 227–254. doi:10.1017/S0963926807004622.

- ^ Bassett 2019.

- ^ a b Young Lee 2008, p. 110–111.

- ^ a b Lester 1892, p. 8.

- ^ Young Lee 2008, p. 110.

- ^ Salt 1921, p. 148.

- ^ British Museum Staff 1902, p. 2.

- ^ Lester 1892, p. 1.

- ^ a b Stratton, Jude & Coulson 1896, p. 46.

- ^ Lester 1892, p. 20.

- ^ The Zoophilist Staff 1893, p. 316.

- ^ Worldcat Staff 2020.

- ^ Lester 1892, p. 3.

- ^ Lester 1892, p. 4.

- ^ Lester 1892, p. 5–7.

- ^ Lester 1892, p. 7.

- ^ Lester 1892, p. 9–12.

- ^ Lester 1892, p. 12–18.

- ^ Young Lee 2008, p. 111.

Sources

[edit]- Bassett, Troy J. (31 December 2019), "Author Information: Horace Frank Lester", At the Circulating Library

- British Museum Staff (1902), Subject Index of the Modern Works Added to the Library of the British Museum in the Years 1881-1900

- Lester, Horace Francis (1892). . The Humanitarian League – via Wikisource.

- Salt, Henry S. (1921), Seventy Years Among the Savages, George Allen & Unwin Limited

- Stratton, J.; Jude, R. H.; Coulson, W. Lisle B. (1896), So-called Sport: A Plea for Strengthening the Law for the Protection of Animals

- Vegan Picks Staff (7 March 2020), "Vegan History: The Humanitarian League's Publications No. V", Vegan Picks

- Worldcat Staff (2020), "Behind the Scenes in Slaughter-Houses", WorldCat, OCLC 1116272431

- Young Lee, Paula (2008), Meat, Modernity, and the Rise of the Slaughterhouse, UPNE, ISBN 9781584656982

- The Zoophilist Staff (1893), "The Humanitarian League", The Zoophilist, vol. 12

External links

[edit] Media related to Behind the Scenes in Slaughter-Houses at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Behind the Scenes in Slaughter-Houses at Wikimedia Commons- Behind the Scenes in the Slaughter-Houses in libraries (WorldCat catalog)