RAF Honiley

| RAF Honiley | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wroxall, Warwickshire in England | |||||||||||

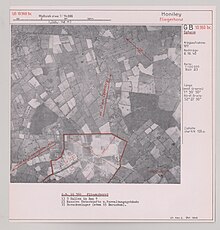

The main runway at RAF Honiley (looking east to west) | |||||||||||

| Coordinates | 52°21′22″N 001°39′54″W / 52.35611°N 1.66500°W | ||||||||||

| Type | Royal Air Force sector station 1941-44 | ||||||||||

| Code | HY[1] | ||||||||||

| Site information | |||||||||||

| Owner | Air Ministry | ||||||||||

| Operator | Royal Air Force | ||||||||||

| Controlled by | RAF Fighter Command 1941-44 * No. 9 Group RAF RAF Bomber Command 1944- * No. 26 (Signals) Group RAF | ||||||||||

| Site history | |||||||||||

| Built | 1940/41 | ||||||||||

| Built by | John Laing & Son Ltd | ||||||||||

| In use | August 1941 – March 1958 | ||||||||||

| Battles/wars | European theatre of World War II | ||||||||||

| Airfield information | |||||||||||

| Identifiers | IATA: BHY | ||||||||||

| Elevation | 141 metres (463 ft)[1] AMSL | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Royal Air Force Honiley or RAF Honiley is a former Royal Air Force station located in Wroxall, Warwickshire, 7 miles (11 km) southwest of Coventry, England.

The station closed in March 1958, and after being used as a motor vehicle test track, it has been subject to planning permission from the Prodrive Formula One team for development of their Fulcrum test and development facility however this has been cancelled.

From September 2014 the site has been used by Jaguar Land Rover for heritage driving experiences with the location being known as Fen End.

History

[edit]

Royal Air Force use

[edit]Originally called Ramsey, it was renamed RAF Honiley in August 1941, and used by a variety of squadrons defending the Midlands during the Second World War.[2]

Squadrons

[edit]- No. 32 Squadron RAF joined the airfield on 9 September 1942 flying the Hawker Hurricane IIB/IIC before moving to RAF Baginton on 18 October 1942.[3]

- No. 91 Squadron RAF began flying from the station on 20 April 1943 flying the Supermarine Spitfire XII before moving to RAF Kings Cliffe on 9 May 1943.[4]

- No. 96 Squadron RAF starting flying at the airfield on 20 October 1942 with the Bristol Beaufighter II/VI and the de Havilland Mosquito XII. The squadron left on 4 August 1943 and moved to RAF Tangmere.[5]

- No. 130 Squadron RAF moved to the airfield on 5 July 1943 flying the Spitfire VA/VB/VC before moving to RAF West Malling on 4 August 1943.[6]

- No. 135 Squadron RAF arrived from RAF Baginton on 4 September 1941 flying the Hurricane IIA before embarking for the far east on 10 November 1941 arriving at Zayatkwin.[7]

- No. 219 Squadron RAF moved from RAF Woodvale on 15 March 1944 and stayed until 26 March 1944 flying the de Havilland Mosquito XVII before moving to RAF Colerne.[8]

- No. 234 Squadron RAF moved from RAF Church Stanton on 8 July 1943 and stayed until 5 August 1943 flying the Spitfire VB/VC before moving to RAF West Malling.[9]

- No. 255 Squadron RAF moved from RAF High Ercall between 6 June 1942 flying the Bristol Beaufighter VI before moving to North Africa on 13 November 1942.[10]

- No. 257 Squadron RAF started using the airfield from 7 November 1941 before this the squadron was at RAF Coltishall. The squadron flying both the Hawker Hurricane I/IIA/IIB/IIC and the Spitfire VB until 6 June 1942 when the squadron moved to RAF High Ercall.[11]

- No. 285 Squadron RAF came from RAF Wrexham on 29 October 1942 flying the Airspeed Oxford I/II and the Boulton Paul Defiant I/III before moving to RAF Woodvale on 27 August 1943.[12]

- No. 605 "County of Warwick" Squadron AAF (renamed to RAuxAF) came from B.80 Volkel on 10 May 1946 flying the Mosquito NF.30 and de Havilland Vampire F.1/FB.5 until 10 March 1957 when the squadron was disbanded.[13][14]

Other units

[edit]- 1456 (Turbinlite) Flt using the Douglas Boston.[15]

- August 1943 to March 1944 – No. 63 Operational Training Unit RAF instructing Airborne Interception techniques with Bristol Beaufighters and Blenheims. Moved to RAF Cranfield.[15]

- July 1944 to August 1946 – ground units transferred to 26 Signals Group, RAF Bomber Command. Renamed Signals Flying Unit RAF in July 1944, testing new radio equipment. Moved to RAF Watton in August 1946.[15]

- August 1946 to March 1957 – 1833 Naval Air Squadron Royal Naval Reserve with de Havilland Sea Vampires then Supermarine Attackers.[16]

Additional units:

- No. 3 Tactical Exercise Unit RAF[17]

- No. 6 (Pilots) Advanced Flying Unit RAF[17]

- No. 9 Group Anti-Aircraft Co-operation Flight RAF[17]

- No. 16 Service Flying Training School RAF[17]

- No. 18 (Pilots) Advanced Flying Unit RAF[17]

- No. 20 Service Flying Training School RAF[17]

- No. 41 Gliding School RAF[17]

- No. 60 OTU[17]

- 416th Night Fighter Squadron[17]

- 718 Naval Air Squadron[17]

- No. 2734 Squadron RAF Regiment[17]

- No. 2809 Squadron RAF Regiment[17]

- No. 2832 Squadron RAF Regiment[17]

- No. 3208 Servicing Commando[17]

- Ground Controlled Approach Flight RAF[18]

- Ground Controlled Approach Squadron RAF[18]

- Reserve Command Instrument Training Flight[19] became the Home Command Instrument Training Flight[20]

- Reserve Command Major Servicing Unit became the Home Command Major Servicing Unit[17]

From April 1957, the station was placed on Care and Maintenance until closure.[15]

Facilities

[edit]The airfield had 15 hangars; there were three Bellmans and 12 Blister hangars. There was also a cinema and technical workshops.[15]

Post Royal Air Force use

[edit]After being taken over by LucasVarity for vehicle testing, residents have included Prodrive, Marcos and TRW.[21]

In addition to their existing automotive consultancy business, which was based at the site from 2001, in March 2006 motor racing company Prodrive announced its intent to build a £200 million, 200-acre (0.8 km2) motorsport facility called The Fulcrum.[22] Prodrive's statement in the planning application for the facility – which could house as many as 1,000 staff – boasted of "a motorsport complex which could eventually house Prodrive's new British Prodrive F1 team", further cementing Managing Director David Richards' intention to return to F1 in 2008.[23]

As of 3 August 2006, Prodrive won the support of the Warwick District Council planning committee for development of The Fulcrum.[24] The permission covered a highly advanced engineering research and development campus, a conference facility called the Catalyst Centre and new access road, a roundabout, infrastructure, parking and landscaping. The plans still had to be presented and agreed by the British government's Department for Communities and Local Government, and there was local opposition via the Fulcrum Prodrive Action Group (FPAG) to protect the rural nature of the community and the safety of the people that live within it.[21]

However, following rule changes banning so-called 'customer' cars from competing in F1, and legal proceedings undertaken by existing F1 manufacturer teams, Prodrive's F1 plans were shelved indefinitely. Since the sale of the site to Jaguar Land Rover in 2014, Prodrive's business remains based at their Banbury headquarters.[25]

It is also the site of the HON (Honiley) VOR-DME navigation aid, which is positioned to the south of the track.[26]

The old turbine development buildings, previously re-purposed and used as administration offices by Lucas Automotive have been left by Prodrive in the same state they were when Lucas first vacated the site and have become a popular site for Urban Explorers.[27]

Present day

[edit]In 2011, the disused administrative building on the site was used as a set by the metalcore band Oceans Ate Alaska in the music video for their debut single Clocks.[28]

The site was purchased by Jaguar Land Rover in 2014[29] who moved their Heritage Driving Experience[30] operations to it from their Gaydon facility based at the former RAF Gaydon. It currently (as of December 2017) also houses their press car operations, as well as part of their Special Vehicle Operations division.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Falconer 2012, p. 112.

- ^ "A Night-time Emergency Landing". BBC – WW2 People's War. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ Halley 1988, p. 79.

- ^ Halley 1988, p. 163.

- ^ Halley 1988, p. 169.

- ^ Halley 1988, p. 205.

- ^ Halley 1988, p. 209.

- ^ Halley 1988, p. 285.

- ^ Halley 1988, p. 302.

- ^ Halley 1988, p. 323.

- ^ Halley 1988, p. 325.

- ^ Halley 1988, p. 348.

- ^ Halley 1988, p. 423.

- ^ "605 Squadron". 605 Squadron County of Warwick Squadron. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d e "RAF Honiley". Control Towers. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ "History of Bramcote Station". Ministry of Defence – British Army. Archived from the original on 13 March 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Honiley". Airfields of Britain Conservation Trust. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ a b Lake 1999, p. 118.

- ^ Lake 1999, p. 171.

- ^ Lake 1999, p. 130.

- ^ a b Protest against Formula One plans[permanent dead link] kenilworthweeklynews.co.uk – 24 March 2006

- ^ Prodrive plans £200m F1 facility itv-f1.com – 13 March 2006 Archived 4 March 2006 at the National and University Library of Iceland

- ^ New Formula One plans unveiled BBC News – 1 March 2006

- ^ Prodrive development approved[permanent dead link] kenilworthweeklynews.co.uk – 3 August 2006

- ^ "Relocation & Development". Prodrive. Archived from the original on 22 May 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ^ "UK Aviation NavAids Gallery". Trevor Diamond. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ^ "Report – RAF Honiley, Warwickshire". 28 Days Later. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Oceans Ate Alaska – "Clocks" – Official Video – via YouTube.

- ^ "Jaguar Land Rover buys new test track in Warwickshire". ITV News. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ "Contact". Heritage Driving. Archived from the original on 29 May 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

Bibliography

[edit]- Falconer, J. (2012). RAF Airfields of World War 2. UK: Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85780-349-5.

- Halley, James J. The Squadrons of the Royal Air Force & Commonwealth, 1981-1988. Tonbridge, Kent, UK: Air-Britain (Historians) Ltd., 1988. ISBN 0-85130-164-9.

- Lake, A (1999). Flying units of the RAF. Shrewsbury: Airlife. ISBN 1-84037-086-6.

External links

[edit]- Fulcrum Prodrive Action Group Archived 13 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine