Copies by Vincent van Gogh

| Noon - Rest from Work (after Millet) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Vincent van Gogh |

| Year | 1890 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Location | Musée d'Orsay, Paris |

Vincent van Gogh made many copies of other people's work between 1887 and early 1890, which can be considered appropriation art.[1][2] While at Saint-Paul asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, France, where Van Gogh admitted himself, he strived to have subjects during the cold winter months. Seeking to be reinvigorated artistically, Van Gogh did more than 30 copies of works by some of his favorite artists. About twenty-one of the works were copies after, or inspired by, Jean-François Millet. Rather than replicate, Van Gogh sought to translate the subjects and composition through his perspective, color, and technique. Spiritual meaning and emotional comfort were expressed through symbolism and color. His brother Theo van Gogh would call the pieces in the series some of his best work.

Background

[edit]During the winter months at Saint-Remy Van Gogh had a shortage of subjects for his work. Residing at Saint-Paul asylum, he did not have the freedom he enjoyed in the past, the weather was too cold to work outdoors and he did not have access to models for paintings. Van Gogh took up copying some of his favorite works of others,[3][4] which became the primary source of his work during the winter months.[5] The Pietà (after Delacroix) marks the start of a series of paintings that Van Gogh made after artists such as Jean-François Millet, Honoré Daumier and Rembrandt. Millet's work, who greatly influenced Van Gogh, figures prominently in this series. He wrote to Theo about these copies: "I started making them inadvertently and now find that I can learn from them and that they give me a kind of comfort. My brush then moves through my fingers like a bow over the strings of a violin – completely for my pleasure."[4]

Several religious works, such as The Pietà, were included in the series, notable exceptions in his oeuvre. Saint-Paul asylum, housed in an old monastery, may have provided some of the inspiration for the specific subject. The nuns devoutness sometimes annoyed him, but he did find solace in religion. He wrote: "I am not indifferent, and pious thoughts often console me in my suffering."[4]

Van Gogh Museum asserts that Van Gogh may have identified with Christ "who had also suffered and been misunderstood." They also offer the conjecture of some scholars of a resemblance between the Van Gogh and the red-bearded Christ in The Pietà and Lazarus in the copy after Rembrandt. However it is unknown whether or not this was Van Gogh's intention.[4]

Copy after Émile Bernard

[edit]Émile Bernard, an artist and Catholic mystic, was a close personal friend to Van Gogh. Bernard influenced Van Gogh artistically several ways. Bernard outlined figures in black, replicating the look of religious woodcut images of the Middle Ages. This resulted in a flattened, more primitive work. Van Gogh's Crows over the Wheatfield is one example of how Bernard's simplified form influenced his work.[6] Bernard also taught Van Gogh about how to manipulate perspective in his work. Just as Van Gogh used color to express emotion, he used distortion of perspective as a means of artistic expression and a vehicle to "modernize" his work.[7]

As a demonstration of the sharing of artistic viewpoints, Van Gogh painted a copy in watercolor of a sketch made by Bernard of Breton woman. Van Gogh wrote to Bernard of a utopian ideal where artists worked cooperatively, focused on a common idea, to reach heights artistically "beyond the power of the isolated individual." As a means of clarification, he stated that did not mean that several painters would work on the same picture, but they will each create a work that "nonetheless belong together and complement each other." The Breton Women is one of many examples of how Van Gogh and one of his friend's brought their unique temperaments and skills to a single idea.[8]

Van Gogh wrote to Bernard his trade of the Breton Women to Paul Gauguin: "Let me make it perfectly clear that I was looking forward to seeing the sort of things that are in that painting of yours which Gauguin has, those Breton women walking in a meadow so beautifully composed, the colour with such naive distinction."[9] Gauguin made a work, Breton Women at a Pardon which was may have been inspired by Bernard's work of Breton women.[10]

-

Breton Women in the Meadow by Émile Bernard, August 1888

-

Vincent van Gogh, Breton Women and Children, November 1888, Civica Galleria d'Arte Moderna, Milan, Italy (F1422)

Copy after Virginie Demont Breton

[edit]Van Gogh painted a work of the engraving Man at Sea made by Virginie Demont-Breton, daughter of Jules Breton. Her engraving was exhibited at the Salon of 1889.[11] The picture depicts, almost entirely in shades of violet, a peaceful scene of a mother sitting by a fire with her baby on her lap.[12]

-

Her Man is at Sea by Virginie Demont-Breton

-

The Man is at Sea (after Demont-Breton), 1889, Private collection (F644)

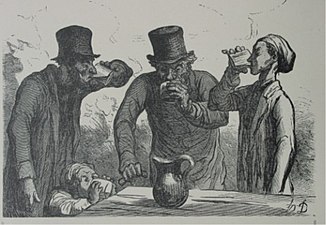

Copy after Honoré Daumier

[edit]In 1882 Van Gogh had remarked that he found Honoré Daumier's The Four Ages of a Drinker both beautiful and soulful.[13]

Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo of Daumier's artistic perspective and humanity: "What impressed me so much at the time was something so stout and manly in Daumier's conception, something that made me think It must be good to think and to feel like that and to overlook or ignore a multitude of things and to concentrate on what makes us sit up and think and what touches us as human beings more directly and personally than meadows or clouds."[14] Daumier's artistic talents included painting, sculpting and creating lithographs. He was well known for his social and political commentary.[15]

Van Gogh made Men Drinking after Daumier's work in Saint-Remy about February 1890.[16]

-

Honoré Daumier, The Drinkers, 1862; from Monde Illustré, 25 October 1862, under the title "Physiologie du buveur, les quatre ages" ("Psychology of drinkers, the four ages")

-

Vincent van Gogh, Men Drinking (after Daumier), 1890, The Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois (F667)

Copies after Eugène Delacroix

[edit]Background

[edit]Van Gogh, motivated by the book The Imitation of Christ which included depiction of Christ as a suffering servant, worked on reprises of Eugène Delacroix's Pieta and Good Samaritan. Rather than representing "a triumphant Christ in glory," he depicted Christ in his most perilous and painful period, his crucifixion and death.[17] Of capturing the scenes of his religious work from long ago, Van Gogh described Delacroix's perspective of how to paint the historical religious figures: "Eug. Delacroix, when he did a Gethsemane, had been beforehand to see what an olive grove was like on the spot, and the same for the sea whipped up by a strong mistral, and because he must have said to himself, these people we know from history, doges of Venice, crusaders, apostles, holy women, were of the same type as, and lived in a similar way to, their present-day descendants."[18]

Delacroix's influence helped Van Gogh develop artistically and gain knowledge of color theory. To his brother Theo, he wrote: "What I admire so much about Delacroix... is that he makes us feel the life of things, and the expression of movement, that he absolutely dominates his colours."[19]

Table of paintings

[edit]| Van Gogh Image | Name and Details | Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

The Good Samaritan (after Delacroix) 1890 Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F630) |

In 1889 Van Gogh expressed a desire to make copies of paintings, including The Good Samaritan by Delacroix as a learning experience.[20] |

|

The Pietà (after Delacroix), first version 1889 Vatican Collection of Modern Religious Art, Vatican City (F757) |

Van Gogh made the Pietà paintings from a lithograph of Delacroix's painting. The subject and composition from the original remain, but Van Gogh brings his own style to the artwork.[4] Of the Pietà, Van Gogh writes: "The Delacroix is a "Pietà" that is to say the dead Christ with the Mater Dolorosa. The exhausted corpse lies on the ground in the entrance of a cave, the hands held before it on the left side, and the woman is behind it. It is in the evening after a thunderstorm, and that forlorn figure in blue clothes - the loose clothes are agitated by the wind - is sharply outlined against a sky in which violet clouds with golden edges are floating. She too stretches out her empty arms before her in a large gesture of despair, and one sees the good sturdy hands of a working woman. The shape of the figure with its streaming clothes is nearly as broad as it is high. And the face of the dead man is in the shadow - but the pale head of the woman stands out clearly against a cloud - a contrast which causes those two heads to seem like one somber-hued flower and one pale flower, arranged in such a way as mutually to intensify the effect."[21] |

|

The Pietà (after Delacroix) 1889 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands (F630) |

The Van Gogh Museum relates how Van Gogh hastily began work on the Pietà: "The Delacroix lithograph La Pietà, as well as several others, fell into my oils and paints and was damaged. This upset me terribly, and I am now busy making a painting of it, as you will see." Although stained, the lithograph survived.[4] |

Copy after Gustave Doré

[edit]Prisoners' Round (after Gustave Doré) was made by Van Gogh at Saint-Paul asylum in Saint-Rémy. This work like the reprises of Eugène Delacroix and Rembrandt's works, evokes Van Gogh's sense of isolation, like an imprisoned or dying man. Although sad, there is a sense of comfort offered.[22] In a letter to his brother, Theo, Van Gogh mentioned that he found making it and Men Drinking (after Daumier) quite difficult.[16]

-

Gustave Doré, Newgate Exercise yard, from London: A Pilgrimage by Gustave Doré and Blanchard Jerrold, 1872

-

Vincent van Gogh, Prisoners' Round (after Gustave Doré), 1890, Pushkin Museum, Moscow, Russia (F669)

Following Van Gogh's funeral, Émile Bernard wrote of the studies around his coffin: "On the walls of the room where his body was laid out all his last canvases were hung making a sort of halo for him and the brilliance of the genius that radiated from them made this death even more painful for us artists who were there." Of the Doré reprise, he said, "Convicts walking in a circle surrounded by high prison walls, a canvas inspired by Doré of a terrifying ferocity and which is also symbolic of his end. Wasn't life like that for him, a high prison like this with such high walls - so high…and these people walking endlessly round this pit, weren't they the poor artists, the poor damned souls walking past under the whip of Destiny?"[23]

Copy after Keisai Eisen

[edit]While living in Antwerp Van Gogh become acquainted with Japanese wood block prints. In Paris, Keisai Eisen's print appeared on the May 1886 cover of Paris Illustré magazine which inspired Van Gogh to make The Courtesan.[24][25] The magazine issue was entirely devoted to Japan. Japanese author, Tadamasa Hayashi, who lived in Paris, acquainted Parisians with information about Japan. In addition to providing information about its history, climate and visual arts, Hayashi explained what it was like to live in Japan, such as its customs, religion, education, religion, and the nature of its people.[25]

Van Gogh copied and enlarged the image. He created a bright yellow background and colorful kimono. Influenced by other Japanese prints, he added a "watery landscape" of bamboo and water lilies. Frogs and cranes, terms used in 19th century France for prostitutes, with a distance boat adorn the border.[24]

-

A courtesan, Nishiki-e, by Keisai Eisen

-

The Courtesan (after Eisen) by Vincent van Gogh, 1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F373)

Copies after Utagawa Hiroshige

[edit]In the mid-19th century Japan opened itself to trade, making Japanese art available to the west.[26] The works of Japanese print makers, Hiroshige and Hokusai greatly influenced Van Gogh, both for the beautiful subject matter and the style of flat patterns of colors, without shadow. Van Gogh collected hundreds of Japanese prints and likened the works of the great Japanese artists, like Hiroshige, to those of Rembrandt, Hals, and Vermeer. Van Gogh explored the various influences, molding them into a style that was uniquely his own.[27] The Japanese paintings represent Van Gogh's search for serenity, which he describes in a letter to his sister during this period, "Having as much of this serenity as possible, even though one knows little – nothing – for certain, is perhaps a better remedy for all diseases than all the things that are sold at the chemist's shop."[5][28]

Hiroshige, one of the last great masters of Ukiyo-e, was well known for series of prints of famous Japanese landmarks.[29]

Japonaiserie: Flowering Plum Tree (after Hiroshige)

[edit]The Flowering Plum Tree is believed to be the first of three oil paintings made by Van Gogh of Utagawa Hiroshige's Japanese woodblock prints. He used color to emulate the effect of the printer's ink, such as the red and greens in the background and the tint of green on the white blossoms. After he moved to Arles, Van Gogh wrote to his sister that he no longer needed to dream of going to Japan, "because I am always telling myself that here I am in Japan."[30]

-

The Plum Orchard In Kameido by Hiroshige

-

Japonaiserie: Flowering Plum Tree (after Hiroshige), by Vincent van Gogh, 1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F371)

Japonaiserie: Bridge in the Rain (after Hiroshige)

[edit]Utagawa Hiroshige's Evening Shower at Atake and the Great Bridge woodcut, which he had in his collection,[31] inspired Van Gogh for its simplicity. The cloudburst, for instance, is conveyed by parallel lines. Such techniques were revered, but also difficult to execute when creating the wood block stamp for printing. By making a painting, Van Gogh's brushstrokes "softened the boldness of the Japanese woodcut."[27] Calligraphic figures, borrowed from other Japanese prints, fill the border around the image. Rather than following the color patterns of the original woodcut print, he used bright colors or contrasting colors.[31]

-

Evening Shower at Atake and the Great Bridge, by Hiroshige

-

Japonaiserie: Bridge in the Rain (after Hiroshige), by Vincent van Gogh, 1887, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F372)

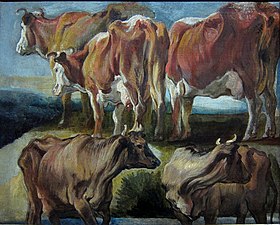

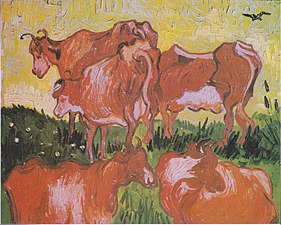

Copy after Jacob Jordaens

[edit]Van Gogh used Jordaen's subject and composition for his rendition of Cows. A later artist, Edward Hopper, also used Jordaen's Cows as a source of inspiration for his work.[32] The painting is located at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lille in France.[33] Jan Hulsker notes that the painting is a color study of an etching Dr. Gachet made of Jordaen's painting.[34]

-

Cows, Jordaens

-

Cows (after Jordaens) 1890 Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille, Lille, France (F822, JH2095)

Copies after Jean-François Millet

[edit]

Background

[edit]The "peasant genre" that greatly influenced Van Gogh began in the 1840s with the works of Jean-François Millet, Jules Breton, and others. In 1885 Van Gogh described the painting of peasants as the most essential contribution to modern art. He described the works of Millet and Breton of religious significance, "something on high."[35] A common denominator in his favored authors and artists was sentimental treatment of the destitute and downtrodden. He held laborers up to a high standard of how dedicatedly he should approach painting, "One must undertake with confidence, with a certain assurance that one is doing a reasonable thing, like the farmer who drives his plow... (one who) drags the harrow behind himself. If one hasn't a horse, one is one's own horse." Referring to painting of peasants Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo: "How shall I ever manage to paint what I love so much?"[36]

Van Gogh Museum says of Millet's influence on Van Gogh: "Millet's paintings, with their unprecedented depictions of peasants and their labors, mark a turning point in 19th-century art. Before Millet, peasant figures were just one of many elements in picturesque or nostalgic scenes. In Millet's work, individual men and women became heroic and real. Millet was the only major artist of the Barbizon School who was not interested in 'pure' landscape painting."[37]

Van Gogh made twenty-one paintings in Saint-Rémy that were "translations" of the work of Jean-François Millet. Van Gogh did not intend for his works to be literal copies of the originals. Speaking specifically of the works after Millet, he explained, "it's not copying pure and simple that one would be doing. It is rather translating into another language, the one of colors, the impressions of chiaroscuro and white and black."[38] He made a copy of The Gleaners (Des glaneuses) by Millet.

Theo wrote Van Gogh: "The copies after Millet are perhaps the best things you have done yet, and induce me to believe that on the day you turn to painting compositions of figures, we may look forward to great surprises."[39]

Table of paintings

[edit]| Millet Image | Van Gogh Image | Comments |

|---|---|---|

Morning: Going to Work ca. 1858-60 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands |

Morning: Peasant Couple Going to Work 1890 Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia (F684) |

Millet created a series of woodcuts entitled The Four Hours of the Day (1860). This idea is reportedly derived from the medieval "Book of Hours" that held that rural life was structured by the rhythms of God and nature.[38] In this work, the man and woman walk to the fields, silhouetted by the morning sun. The simple composition depicts the harshness of their lives. Van Gogh said of Millet's work, "they seem to have been painted with the very earth they were going to till."[40] |

Noon: Rest 1866 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

The Siesta or Noon - Rest from Work 1890 Musée d'Orsay, Paris, France (F686) |

While remaining true to Millet's composition, Van Gogh uses color to depict the peaceful nature of the mid-day rest. Use of contrasting colors, blue-violet against yellow-orange brings an intensity to the work that is uniquely his style.[41] |

The End of the Day 1867-69 Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester, Rochester |

Man in a Field or Evening, the End of the Day November 1889 Menard Art Museum, Komaki, Japan (F649) |

In this work the farmer ends his day against the background of an evening sky. Van Gogh painted vivid colors of yellow and violet in his unique pointillistic style. While he brands the work with his own style, he remains true to Millet's composition.[42] |

Night 1867 Fine Arts Museum, Boston |

|

The work depicts happy life of a rural family: father, mother and child. Here the image seems bathed in yellow light like that of the Holy Family.[43] A lamp casts long shadows of many colors on the floor of the humble cottage. The painting includes soft shades of green and purple. The work was based on a print by Millet from his series, the four times of day.[44] |

First Steps ca. 1858 Lauren Rogers Museum of Art, Laurel, Mississippi |

First Steps 1890 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (F668) |

Van Gogh used a photograph of the original painting for this work.[45] Rather than vibrant colors, here he used softer shades of yellow, green and blue. The picture depicts the father, having put down his tools, holding his arms outstretched for his child's first steps. The mother protectively guides the child's movement.[46] |

1850 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

The Sower 1889 Niarchos Collection, Zurich (F690) |

Having made over 30 works of the sower, Van Gogh explored the symbolism of sowing: "One does not expect to get from life what one has already learned it cannot give; rather, one begins to see more clearly that life is a kind of sowing time, and the harvest is not yet here."[47] As the sower cast seeds, another farmer is seen in a nearby field ploughing the field. Van Gogh depicted the sower in "its simplest form" and with the colors of blue, red, yellow, purple and orange, giving life and meaning to the composition of the eternal cycles of life.[48] |

1850 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

The Sower 1889 Kroller-Muller Museum (F689) |

Van Gogh's appreciation for Millet's work stemmed from the soulfulness he brought to the works, specifically honoring peasants' agricultural role. Plowing, sowing, and harvesting were seen by Van Gogh as symbols for man's command of nature and its eternal cycles of life.[49] Kay Larson of New York Magazine wrote of Millet's work: The Sower, who strides like an elemental force of nature across the cold, newly broken earth, is such an icon that Simon & Schuster uses it as a logo."[50] |

|

The Reaper 1889 Private Collection (F688) |

In man's mastery of the cycles of nature: "the sower and the wheat sheaf stood for eternity, and the reaper and his scythe for irrevocable death."[35] Of the reaper Van Gogh expressed his symbolic, spiritual view of those who worked close to nature in a letter to his sister in 1889: "aren’t we, who live on bread, to a considerable extent like wheat, at least aren't we forced to submit to growing like a plant without the power to move, by which I mean in whatever way our imagination impels us, and to being reaped when we are ripe, like the same wheat?"[51]

Van Gogh spoke of the symbolic meaning of the reaper: "For I see in this reaper — a vague figure fighting like a devil in the midst of the heat to get to the end of his task — I see in him the image of death, in the sense that humanity might be the wheat he is reaping. So it is — if you like — the opposite of that sower I tried to do before. But there is nothing sad in this death, it goes its way in broad daylight with sun flooding everything with a light of pure gold."[52] |

|

The Reaper with a Sickle 1889 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands (F687) |

Of making this painting, and others of Millet's Work in the Field series, Van Gogh mentioned that absent models, he was pleased to have seven of the ten in the series completed.[53] |

|

Peasant Woman with a Rake 1889 Private collection (F698) |

|

|

Peasant Woman Binding Sheaves 1889 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands (F700) |

In Peasant Woman Binding Sheaves (after Millet) Van Gogh's work shows it is beautiful for its simplicity and appreciation of nature. The woman's expression is hidden to us and appears like one of the waiting bundles of wheat. The true focus of the scene is the woman's bent back.[54] |

|

The Sheaf-Binder 1889 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands (F693) |

|

|

Peasant Woman Cutting Straw 1889 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F697) |

|

|

The Thresher 1889 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands (F692) |

|

1866 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

Two Peasants Digging 1889 The Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands (F648) |

|

| The Woodcutter ca. 1853 Musée du Louvre, Paris |

The Woodcutter 1890 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F670) |

|

Shearing Sheep ca. 1852-53 Museum of Fine Art, Boston |

The Sheep-Shearers 1889 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands (F634) |

|

La grande bergère assise Woodcut, c. 1874 Various collections |

The Shepherdess 1889 Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Israel (F699) |

The source was a woodcut (27.3 x 21.9 cm) by Jean-Baptise Millet after his brother Jean-François Millet. Its strong contour line was the inspiration for Vincent van Gogh's Sorrow.[55] |

|

Woman Spinning 1889 Collection Sara and Moshe Mayer, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Israel (F696) |

|

| Winter: The Plain of Chailly 1862 Osterreichische Gallerie, Vienna |

Snow covered Field with a Harrow or Plough and the Harrow January, 1890 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands (F632) |

Van Gogh used Millet's work, and Alfred Delaunay's etching of Millet's work, as inspiration for this painting. In Van Gogh's version he added black crows and made the winter scene more bleak, deserted and cold. His choice of color, composition and brushstroke make this work uniquely his own.[56] |

|

Two Peasant Women Digging in the Snow April, 1890 Foundation E.G. Bührle, Zurich, Switzerland (F695) |

Van Gogh used the women from Millet's The Gleaners as inspiration for this painting of women digging in the frozen snow. Unlike the others, this work is not a literal translation of the original painting. The setting sun casts a warm glow over the fields of snow. The cool colors of the field contrast to the red in the sun and sky.[57] Jan Hulsker places the painting as one of van Gogh's "reminisces of the North". |

Copies after Rembrandt

[edit]From Rembrandt, Van Gogh learned how to paint light into darkness. Rembrandt's influence seemed present one evening in 1877 when Van Gogh walked through Amsterdam. He wrote: "the ground was dark, the sky still lit by the glow of the sun, already gone down, the row of houses and towers standing out above, the lights in the windows everywhere, everything reflected in the water." Van Gogh found Rembrandt particularly adept at his observation of nature and expressing emotion with great tenderness.[49]

It's not clear if Van Gogh was copying after particular Rembrandt works for his copies or the spirit of the figures he portrayed. Examples of Rembrandt's angels and Lazarus are here for illustrative purposes.

-

Abraham with three angels, Rembrandt

-

The Angel Appearing to the Shepherds, Rembrandt

-

Jacob with an angel, Rembrandt 1659

-

Half Figure of an Angel (after Rembrandt) 1889 (F624)

In Van Gogh's version of The Raising of Lazarus (after Rembrandt), Christ is depicted symbolically through the sun to evoke the healing powers of faith. Christ is further referenced in two ways by the setting and circumstance. First, miraculously, he brought Lazarus back to life again. It also foretold Christ's own death and resurrection.[17] The painting includes the dead Lazarus and his two sisters. White, yellow and violet were used for Lazarus and the cave. One of the women is in a vibrant green dress and orange hair. The other wears a striped green and pink gown and has black hair. Behind them is the countryside of blue and a bright yellow sun.[58]

In The Raising of Lazarus (after Rembrandt), van Gogh drastically trimmed the composition of Rembrandt's etching and eliminated the figure of Christ, thus focusing on Lazarus and his sisters. It is speculated that in their countenances may be detected the likenesses of the artist and his friends Augustine Rouline and Marie Ginoux.[59] Van Gogh had just recovered from a lengthy episode of illness, and he may have identified with the miracle of the biblical resurrection, whose "personalities are the characters of my dreams."

-

Resurrection of Lazarus, by Rembrandt

-

The Raising of Lazarus, by Rembrandt

-

The Raising of Lazarus, by Rembrandt

-

The Raising of Lazarus (after Rembrandt) by Vincent van Gogh 1890 Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands (F677)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Van Gogh and Japan review – from strange obsession to lasting impression". The Guardian. 2019-06-04. Retrieved 2021-04-12.

- ^ Small, Zachary (2018-11-20). "The Japanese Prints that Inspired Vincent van Gogh". Hyperallergic. Retrieved 2021-04-12.

- ^ Harrison, R (ed.). "Vincent van Gogh. Letter to Theo van Gogh. Written 24 September 1888 in Arles". van Gogh, J. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f "Pietà (after Delacroix), 1889". Permanent collection > Saint-Rémy - 1889-1890. Van Gogh Museum. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ a b Meier-Graefe, J (1987) [London: Michael Joseph, Ltd. 1936]. Vincent van Gogh: A Biography. Mineola, NY, USA: Dover Publications. pp. 56–57. ISBN 9780486252537.

- ^ Erickson, K (1998). At Eternity's Gate: The Spiritual Vision Of Vincent van Gogh. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdsman Publishing. pp. 150–151. ISBN 0-8028-3856-1.

- ^ Erickson, K (1998). At Eternity's Gate: The Spiritual Vision Of Vincent van Gogh. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdsman Publishing. p. 104. ISBN 0-8028-3856-1.

- ^ Zemel, C (1997). Van Gogh's Progress: Utopia, Modernity, and Late-Nineteenth-Century Art. University of California Press. p. 198. ISBN 9780520088498.

- ^ Harrison, R (ed.). "Vincent van Gogh. Letter to Emile Bernard. Written c. 20 November 1889 in Saint-Rémy". van Gogh, J. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ Dorment, R (July 25, 2006). "Visionary with a paintbrush". The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved April 17, 2011.

- ^ Lacouture, A (2002). Jules Breton, Painter of Peasant Life. Yale University Press. p. 232. ISBN 0-300-09575-9.

- ^ Maurer, N (1999) [1998]. The pursuit of spiritual wisdom: the thought and art of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin. Cranbury: Associated University Presses. p. 96. ISBN 0-8386-3749-3.

- ^ Harrison, R (ed.). "Vincent van Gogh. Letter to Anthon van Rappard. Written 18–19 September 1882 in The Hague". Vincent van Gogh Letters. van Gogh, J. WebExhibits. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ Harrison, R (ed.). "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, The Hague, 22 October 1882". Vincent van Gogh Letters. van Gogh, J. WebExhibits. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ "Daumier and His World, Timeline Introduction". Brandeis University Libraries. 2003. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ a b Harrison, R (ed.). "Vincent van Gogh. Letter to Theo van Gogh. Written 10 or 11 February 1890 in Saint-Rémy". Vincent van Gogh Letters. van Gogh, J. WebExhibits. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ a b Erickson, K (1998). At Eternity's Gate: The Spiritual Vision Of Vincent van Gogh. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdsman Publishing. p. 157. ISBN 0-8028-3856-1.

- ^ Harrison, R (ed.). "Vincent van Gogh. Letter to Theo van Gogh. Written 7 or 8 September 1889 in Saint-Rémy". Van Gogh letters. van Gogh, J. WebExhibits. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ Mancoff, D (1999). Van Gogh's Flowers. London: Frances Lincoln Limited. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-0-7112-2908-2.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Harrison, R (ed.). "Vincent van Gogh. Letter to Theo van Gogh. Written 19 September 1889 in Saint-Rémy". Van Gogh letters. van Gogh, J. WebExhibits. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ Harrison, R (ed.). "Vincent van Gogh. Letter to Wilhelmina van Gogh. Written 19 September 1889 in Saint-Rémy". Van Gogh letters. van Gogh, J. WebExhibits. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ Zemel, C (1997). Van Gogh's Progress: Utopia, Modernity, and Late-Nineteenth-Century Art. University of California Press. p. 165. ISBN 9780520088498.

- ^ Harrison, R (ed.). "Emile Bernard. Letter to Albert Aurier. Written 2 August 1890 in Paris". van Gogh, J. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ a b "The Courtesan (after Eisen), 1887". Permanent Collection, Landscapes. Van Gogh Museum. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ a b "Title page of Paris Illustré "Le Japon' vol. 4, May 1886, no. 45-46". Van Gogh's Literary Sources. Van Gogh Museum. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ "Ando Hiroshige, Japanese Art Influencing Western Art". Ando Hiroshige. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ a b Wallace, R (1969). of Time-Life Books (ed.). The World of Van Gogh (1853-1890). Alexandria, VA, USA: Time-Life Books. p. 70.

- ^ Maurer, N (1999) [1998]. The pursuit of spiritual wisdom: the thought and art of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin. Cranbury: Associated University Presses. pp. 55, 59. ISBN 0-8386-3749-3.

- ^ Mancoff, D (1999). Van Gogh's Flowers. London: Frances Lincoln Limited. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-7112-2908-2.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Mancoff, D (1999). Van Gogh's Flowers. London: Frances Lincoln Limited. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-7112-2908-2.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "The Bridge in the Rain (after Hiroshige), 1887". Permanent Collection, Landscapes. Van Gogh Museum. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ Levin, G (January 1998). Edward Hopper: an intimate biography. University of California Press. p. 130. ISBN 9780520214750.

- ^ Tromp, H (2010). A Real Van Gogh: How the Art World Struggles with Truth. Amsterdam University Press. p. 265. ISBN 9789089641762.

- ^ Hulsker (1980), 474

- ^ a b Van Gogh, V; van Heugten, S; Pissarro, J; Stolwijk, C (2008). Van Gogh and the Colors of the Night. Brusells: Mercatorfonds with Van Gogh Museum and Museum of Modern Art. pp. 12, 25. ISBN 978-0-87070-736-0.

- ^ Wallace, R (1969). The World of Van Gogh (1853-1890). Alexandria, VA, USA: Time-Life Books. pp. 10, 14, 21, 30.

- ^ "Jean-François Millet". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ a b Van Gogh, V; van Heugten, S; Pissarro, J; Stolwijk, C (2008). Van Gogh and the Colors of the Night. Brusells: Mercatorfonds with Van Gogh Museum and Museum of Modern Art. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-87070-736-0.

- ^ Harrison, R (ed.). "Theo van Gogh. Letter to Vincent van Gogh. Written 3 May 1890 in Saint-Rémy". van Gogh, J. WebExhibits. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ Kelvingrove Museum; Art Gallery (2002). Millet to Matisse: Nineteenth- and Twentieth-century French painting. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, with Glasgow Museum. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-902752-65-8.

- ^ "The siesta (after Millet)". Collections. Musee d'Orsay website. 2006. Archived from the original on 2017-04-27. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- ^ "End of the day (after Millet)". Collection, European Art. Menard Art Museum. 2011. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ Zemel, C. Van Gogh's Progress: Utopia, Modernity, and Late-Nineteenth-Century Art. p. 17.

- ^ "Night (after Millet), 1889". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ "Vincent van Gogh: First Steps, after Millet". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. December 2008. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ Maurer, N (1999) [1998]. The Pursuit of Spiritual Wisdom: The Thought and Art of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin. Cranbury: Associated University Press. p. 99. ISBN 0-8386-3749-3.

- ^ Erickson, K (1998). At Eternity's Gate: The Spiritual Vision Of Vincent van Gogh. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdsman Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 0-8028-3856-1.

- ^ Meier-Graefe, J (1987) [London: Michael Joseph, Ltd. 1936]. Vincent van Gogh: A Biography. Mineola, NY, USA: Dover Publications. pp. 202–203. ISBN 9780486252537.

- ^ a b Van Gogh, V; van Heugten, S; Pissarro, J; Stolwijk, C (2008). Van Gogh and the Colors of the Night. Brusells: Mercatorfonds with Van Gogh Museum and Museum of Modern Art. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-87070-736-0.

- ^ Larson, K (April 16, 1984). "Poet of Peasants". New York Magazine. 17 (16). New York: News Group Publications: 101. Retrieved April 17, 2011.

- ^ "Wheat Field with Reapers, Auvers" (PDF). Collection. Toledo Museum of Art. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2011. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- ^ Edwards, C (1989). Van Gogh and God: A Creative Spiritual Quest. Chicago: Loyola Press. pp. 120–121. ISBN 0-8294-0621-2.

- ^ Barr, A (1966) [1935]. Vincent van Gogh. United States: Arno Press. p. 134. ISBN 0-7146-2039-4.

- ^ Ross, B (208). Venturing Upon Dizzy Heights: Lectures and Essays on Philosophy, Literature and the Arts. New York: Peter Lang Publishing. p. 55. ISBN 9781433102875.

- ^ "Letter 216: To Theo van Gogh. The Hague, on or about Monday, 10 April 1882". Vincent van Gogh: The Letters. Van Gogh Museum. Note 2.

I thought: how much one can do with one single line!

- ^ "Snow-covered Field with a Harrow (after Millet), 1890". Permanent Collection, Peasant Life. 2005–2011. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ Van Gogh, V; van Heugten, S; Pissarro, J; Stolwijk, C (2008). Van Gogh and the Colors of the Night. Brusells: Mercatorfonds with Van Gogh Museum and Museum of Modern Art. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-87070-736-0.

- ^ "Vincent van Gogh. Letter to Theo van Gogh. Written 3 May 1890 in Saint-Rémy". Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ Sund, J (2000) Van Gogh Face to Face: The Portraits. Thames and Hudson, p. 198. ISBN 0-500-09290-7

Bibliography

[edit]- Hulsker, Jan The Complete Van Gogh. Oxford: Phaidon, 1980. ISBN 0-7148-2028-8